4

Community Involvement

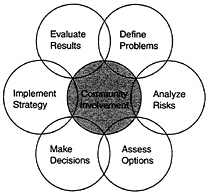

Involving members of a community affected by a contaminated site is critical to the successful completion of a risk-management project. Decisions are less likely to be accepted by a community if the people directly affected by the decisions are not included in the decision-making process. The risk-management framework developed by the Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management (1997) emphasizes that the “stakeholders”1 are “active partners so that different technical perspectives, public values, perceptions, and ethics are considered.” This framework goes beyond the classic EPA model of public participation, which is largely a passive model in which the public provides feedback to the regulatory agencies about decisions made and reports written in closed sessions (EPA 1992).

The active public participation model of the commission’s report is supported by a broad range of research on public participation efforts (NRC

1992; Kunreuther et al. 1993; Ashford and Rest 1999; English et al. 1993; Lynn 1988; NRC 1996; Rich et al. 1995; Hance et al. 1988). Although many important lessons are derived from this research, an essential component for successful implementation of a risk-based framework is the direct and early involvement of all affected parties, including the affected public, as full partners in all parts of the risk-management strategy, including goal setting, evaluating options, setting priorities, evaluating different risk-management strategies, and making a final decision.

This chapter summarizes concerns raised at the public meetings held by the committee during its deliberations. The chapter then discusses the need for community involvement, the benefits, how the community is defined to include both interested and affected parties, and ways to identify and involve the interested and affected parties in the decision-making process. In doing so, the committee presents results from the social science literature and the conclusions drawn by the committee based on the public meetings and on the wealth of information provided to the committee by community and environmental groups; state, tribal, and federal government agencies; and private companies and interests (see Appendix C for a list of these materials).

SPECIFIC COMMUNITY CONCERNS

During the public sessions held in Washington, DC; Green Bay, WI, where the committee visited the Fox River; and Albany, NY, where the committee visited the Hudson River, the committee heard from grassroots community organizations, environmental groups, government agencies, commercial and industrial concerns, and the general public. Some of the following messages were conveyed to the committee at these meetings:

-

The public was dissatisfied with its level of involvement in the management efforts. Involvement was largely limited to commenting on draft documents provided by regulatory agencies. Little active involvement was observed. Participants made it clear that the regulatory agencies have to communicate with the public during all phases of the decision-making process, not just after a decision is made and the public is asked to comment on a completed plan.

-

There was concern about the lack of consideration of indigenous community issues. One speaker from the Mohawk community of Akwesasne described the cultural destruction and community breakdown suffered by Mohawk people, because the PCB contamination along the St. Lawrence River had resulted in fishing advisories, which forced his tribe to stop fishing.

-

That separated the tribe from its traditional life style of fishing for food and for bartering for other goods from farmers. He further stated that it is difficult for some people to understand and respect these concerns and to factor them in when deciding how to clean up the river.

-

Some participants expressed a lack of trust in the government agencies involved at various sites, because the agencies were perceived to be secretive.

-

There were contradictory statements regarding the need to balance short-term risks with long-term benefits. One commenter said that the risks of active remediation (dredging) far outweighed the risks of no remediation, while others said that it was necessary to accept some short-term risks to gain long-term benefits. Other commenters felt that active remediation would not provide any long-term benefits.

-

Farmers expressed concern about the economic impact on their farms if long-term storage sites for dredged PCB-contaminated sediments were located near their property. Concerns focused on whether property values would be reduced and whether their agricultural products would be labeled as “tainted” by PCBs.

-

Businesses were concerned about reduced business opportunities and property values due to adverse publicity associated with remediation in general and with the siting of a long-term storage facility to hold dredged PCB-contaminated sediments. There was also concern about how long it would take to complete the cleanup.

-

One presenter hoped the committee would provide “a critical and unbiased review” of the reports prepared by the government agencies and responsible parties, because he no longer knew what to believe.

-

Some participants criticized the use of natural attenuation, saying that it was a “do-nothing” approach.

Community groups expressed a number of concerns about natural attenuation, particularly that it was a “do-nothing” approach. They stated that natural attenuation is being used or proposed at many sites, because it is inexpensive, not because it provides adequate protection of public health (NRC 2000). Other community groups, such as farmers and marina owners, were concerned that the natural attenuation option be evaluated thoroughly as a viable option for some areas. Natural attenuation processes will be a part of any risk-management strategy, because complete removal of PCB-contaminated sediments cannot be reasonably achieved with present technologies.

Those views were expressed largely by the members of the affected communities. Different views and comments were raised by the regulatory agencies and by the responsible parties. Several of the responsible parties

supported the use of natural recovery and natural attenuation at sites where they were involved and wanted to see cost considerations factored into the risk-management process. There was some disagreement among the regulatory agencies and the responsible parties about the appropriate data, models, and methodologies to be used at the sites.

The public meetings were very important in providing the committee with a first-hand view of the varied and complicated issues surrounding the management of PCB-contaminated sediments. The many different perspectives and concerns of the various interested parties were presented along with a great deal of experiential and technical information. These meetings were an integral and invaluable aid to the committee’s understanding and in its deliberations on how to best reduce the risks associated with managing PCB-contaminated-sediment sites.

DEFINING THE COMMUNITY

Community involvement is a process by which individuals and groups come together in some way to communicate, interact, exchange information, provide input around a particular set of issues, problems, or decisions and share in decision-making to one degree or another (Ashford and Rest 1999). Communities are generally defined as a group of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people (CDC 1997). The community surrounding a contaminated site includes the people who live closest to the site and whose health may be at risk and/or whose property, property values, or economic welfare is adversely affected by the contamination; local business owners; elected officials; local government agency representatives; workers at the site; and others who live farther from the site but who are indirectly affected. The views of these different constituencies might vary substantially, depending on whether their health is at risk and/or their property, property values, or economic welfare is or would be adversely affected by the contamination or the proposed risk-management strategy. In directly affected communities, the members of local organized community efforts do not generally include the regulators or the companies responsible for the contamination as affected parties, at least not in the same way as they include themselves as affected (Ashford and Rest 1999).

Potentially affected parties might include individuals that live by or use the waterway, tribal groups, subsistence or sports fishers who might live near or only occasionally use the water resources, and commercial businesses that rely on fishing, recreational boating, or tourism for subsistence or economic

survival. In the case of PCB-contaminated-sediment sites, identifying who is directly affected is complicated by the fact that many of these sites are large river or estuarine areas that cover many miles. In these instances, communities and businesses downriver may also be affected by contamination occurring upriver. For example, migratory fish contaminated by PCBs at one site might be eaten by people living hundreds of miles away.

Several of these interested and affected parties have different and conflicting values. For example, there are clear differences in perspectives, goals, and objectives between those who are legally responsible for the contamination and its cleanup; those with regulatory oversight and responsibility; those whose health, economic well-being, or quality of life have been or will be affected by the contamination; those who speak on behalf of purely environmental or ecological considerations; those who might be adversely affected by the remediation options; and those who strive to protect the interests of future generations (English et al. 1993).

“Stakeholders” Versus “Affected Parties”

Some studies of public participation and involvement have introduced the notion of a stakeholder (English et al. 1993; Ashford and Rest 1999). Stakeholders are defined broadly as parties with legitimate interest (or stake) in the issues or impending decisions about the contamination (English et al. 1993) and generally consist of representatives of organized constituencies or institutions—industry, labor, environmental groups, government regulators, local government (Ashford and Rest 1999). The president/congressional commission defines stakeholders as “parties who are concerned about or affected by the risk management problem.” Stakeholders may include responsible parties, government regulators, industry and business, elected officials, unions, environmental advocacy groups, consumer-rights organizations, education and research institutions, trade associations, religious groups, and others. The directly affected community may be one of these many parties or may be part of several, but not all, of the many subsets of stakeholders.

In its ideal form, stakeholder involvement treats all stakeholders as equals and attempts to break down the “us/them” notion inherent in public participation (English et al. 1993). However, in its practical form the goals of inclusiveness and representativeness are not always met (Ashford and Rest 1999). The stakeholder approach may be dominated by stakeholders with the most powerful vested interests, effectively diluting the voices of the least powerful members of the community. This concern is supported by the environmental justice literature, which documents that it is sometimes the people who are

most affected by the contamination who have the weakest voice in the remedy (Sexton et al. 1993; IOM 1998) and the least influence on the decision-making process.

Clearly, government and agency officials, responsible parties, and the business community have many resources on which to draw, including the ability to access other powerful interests (Ashford and Rest 1999). Other interested parties, such as national environmental organizations, may also have some resources and a degree of influence, but the grassroots neighborhood groups in the contaminated community generally do not. Nor do members of these groups usually have the time, experience, or resources that they need to participate as equal partners in a stakeholder process. Small-business owners have similar constraints.

The committee distinguishes between members of the community and stakeholders. We prefer the term “affected parties” following the guidance of the NRC Committee on Risk Characterization (NRC 1996). We make this distinction to emphasize the need to identify and include the most affected members of the community, who often are the least powerful and most socially disadvantaged.

The Need for Community Involvement

There is a long tradition of community involvement and public participation in government decision-making going back to the town meetings held in New England over 150 years ago (Folk 1991). During the early 1970s, federal regulations, notably the National Environmental Policy Act, were passed that provided for public participation (O’Brien 2000). The role of public and community involvement changed dramatically during the late 1970s as grassroots community-based organizations (see Box 4-1) formed to represent the interests of the people most directly affected by exposure to chemicals leaking from contaminated sites (Gottlieb 1993; Dowie 1995). Perhaps the most dramatic and well-known of these sites is the Love Canal landfill located in Niagara Falls, NY. More than 900 families were evacuated from this community in 1978 and 1980 following strong organized community efforts (Gibbs 1998). Since that time, literally thousands of similar grassroots organizations have been formed across the country. The database of the Center for Health, Environment, and Justice lists more than 8,000 such groups (Gibbs 1998).

These neighborhood organizations provide a voice in decisions that affect the health and well-being of the community. They provide a focal point for involving interested participants by providing scientific information to the

|

BOX 4–1 Grassroots Community-Based Organizations Grassroots community-based organizations are local neighborhood groups that have formed with the primary purpose of addressing a local contamination problem. Thousands of these organizations have been formed across the country in response to contamination problems. Grassroots organizations do not exist at every PCB-contaminated site, but at some sites, there may be more than one such group. These organizations provide a good base for community involvement in site decision-making. Two grassroots organizations that addressed the committee during visits to the Hudson River area were the Housatonic River Initiative from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and the Arbor Hill Environmental Justice Corporation from Albany, New York. These organizations have been very active in addressing PCB-contaminated sediments issues affecting their communities. |

community, a place to meet, emotional support, a sense of empowerment, and a mechanism for getting community concerns relayed back to other involved parties (Unger et al. 1992; Edelstein 1988). Grassroots groups typically, but not exclusively, consist of people who do not see themselves as environmentalists in a traditional way (Gibbs 1998). Most grassroots community groups are formed not because they choose to get involved in environmental issues but because these issues have intruded upon their lives. It is important, however, not to exclude members of the community who do not participate in or belong to these community-based organizations in the risk-management process. Surveys have found a relatively high level of public trust in these organizations. For example, McCallum et al. (1991) found that survey respondents had five times as much trust in environmental groups (whether local or national) as in chemical industry officials and nearly four times as much trust in these groups as in local and federal officials. Grassroots organizations can provide valuable information that professionals not familiar with the local environment and community might overlook (Ashford and Rest 1999; Brown and Mikkelsen 1997; ATSDR 1996). They might know who is sick and with what disease, have valuable first-hand historical knowledge of past practices that might have led to the contamination, and be familiar with local environmental conditions.

With time, many of these groups lose faith and trust in the institutions that they once believed were established to help protect their interests (Ozonoff and Boden 1987; McCallum et al. 1991; Edelstein 1993; Rich et al. 1995;

Brown and Mikkelsen 1997). Many of these groups also become distrustful of scientific and technical experts from both government and private institutions who often are viewed by the community as being slow to acknowledge hazards, quick to minimize risks, and often prefer to wait for more scientific evidence before taking action to protect public health (Ashford and Rest 1999). These groups—and the public in general—have experienced that science and technical expertise can be frequently politicized (Nelkin 1975; Fiorino 1989; Eden 1996). Furthermore, the interpretation of scientific evidence cannot be completely isolated from personal experiences, social background, and values of any individual providing the interpretation (Ashford 1988). These factors have led to increased transparency of the process and more interaction and participation by these groups in institutional decision-making (Yosie and Herbst 1998; Ashford and Rest 1999).

Benefits of Community Involvement

There are many benefits to involving communities in the risk-management process. Participation makes the process more democratic, lends legitimacy to the process, educates and empowers the affected communities, and generally leads to decisions that are more accepted by the community (Fiorino 1990; Folk 1991; NRC 1996). The affected community members can contribute essential community-based knowledge, information, and insight that is often lacking in expert-driven risk processes (Ashford and Rest 1999). Community involvement can also assist in dealing with perceptions of risk and helping community members to understand the differences between different types and degrees of risk.

When the community is involved in decision-making it is possible that the public will reject or wish to modify a cleanup plan favored by a government agency. However, by participating in the process and being aware of the issues that affect a choice of remediation alternatives, the community will be more likely to accept the compromises that invariably have to be made. A community that has participated in the risk-management plan is less likely to protest the plan after the decision has been made. An example of that benefit is Waukegan Harbor, where the Citizens Advisory Group was an integral part of the remedial action plan (RAP), assisting in the review of the RAP, obtaining cooperation and access from local businesses, and identifying an expanded study area to prevent additional contamination of the harbor. Thus, although getting and keeping the community involved requires additional time and effort from the beginning and throughout the process, the net time spent from problem formulation to final closure can actually decrease.

Several studies have shown that community involvement is likely to result in decreased legal liability, the possibility that new alternatives will emerge, and avoidance of conflicts that can consume resources (Rich et al. 1995; English et al. 1991; Hance et al. 1988). For example, English et al. (1991) found that incorporating the interests of the community can reduce total management costs. Responsible parties, regulators, and community members are likely to benefit from following the basic principles of early community involvement, providing the community with a voice in decision-making, and building an effective relationship with community members.

Another important benefit is that community members can provide the institutional and historical memory about the area that needs to be included in the management plan. Court documents, records of land use, aerial photographs, and official company histories do not always provide full and accurate information. Community members can also identify potentially affected areas by pointing out where changes have occurred in the animal or plant communities or in the physical environment, especially if the changes occurred relatively suddenly.

INVOLVING THE COMMUNITY

As indicated in the risk-based framework presented in Chapter 3, community involvement is an integral component of any strategy to clean up PCB-contaminated sediments, but no one-size-fits-all community involvement plan will work at every site. Each approach must be tailored to the site and its particular social and institutional setting (Renn et al. 1995; English et al. 1993; Kasperson 1986). The process needs to involve all interested and affected parties, who should be considered equals (Box 4-2).

A number of examples of successful community involvement have been documented (Lynn 1988; ATSDR 1996; Ashford and Rest 1999). In reviewing successful case studies, Ashford and Rest (1999) concluded that successful community involvement is a process and that the process should be designed to improve communication with the community, education of community members, and specific participation in information review and decision-making. (See Box 4-3 for an example of a successful community involvement program used by the U.S. Department of Energy.)

Three key principles that have emerged from studies of community involvement are (1) involve the community from the beginning; (2) provide the community with the resources they need to participate effectively in the decision-making process; and (3) build an effective working relationship with the community.

|

BOX 4–2 Community Involvement Principles

|

|

BOX 4–3 Public Participation Programs at the Department of Energy The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has designed a public participation program that involves the appointment of Site-Specific Advisory Boards (SSABs). The SSABs may include representatives of local governments, tribal nations, civic groups, environmental firms, and interested individuals. DOE has assigned obligations to the local site boards that include keeping the boards informed about key issues and upcoming decisions; requesting recommendations well in advance of DOE deadlines; considering and responding in a timely manner to all board recommendations; and providing adequate funding for administrative and technical support. Organized citizen participation has been successful at DOE’s Los Alamos National Laboratory. In one program to characterize site-wide groundwater, an External Advisory Group (EAG) was appointed to advise the responsible managers at the Los Alamos Laboratory concerning the implementation of the hydrogeologic work plan. At the same time, the EAG meets independently with all individual citizens, representatives of citizens groups, tribal nations, and state and federal regulatory representatives. The EAG has effectively acted as facilitator between the external parties’ interest and the managers of the effort to develop the hydrogeologic work plan. During the last 2 years, many of the concerns have been mediated effectively by this process. |

Numerous research studies at contaminated sites have concluded that the best way to build public trust in the selected risk-management plan is to involve the public in the selection process as early as possible rather than involving them after a plan is chosen (Hance et al. 1988; Ashford et al. 1991; English et al. 1991, 1993; Mitchell 1992; Rich et al. 1995; ATSDR 1996; NRC 1996; PCCRARM 1997; Ashford and Rest 1999; Chess and Purcell 1999). These studies support the presidential/congressional commission’s framework approach that community involvement should begin with the initial discovery of contamination or adverse health effects and continue throughout the framework process. The community must be involved in defining the problems and goals for risk management, setting priorities, assessing the risks associated with the contamination, identifying and evaluating different remediation options (such as in the remedial investigation/ feasibility studies process), selecting the final risk-management strategy, and evaluating the efficacy of the management strategy in meeting the goals. Early involvement helps take community members out of a reactive role and offers more meaningful engagement in discussion of options, tradeoffs, and consequences of the issues that need to be addressed (PCCRARM 1997).

Current practice under Superfund and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) limits formal community involvement to commenting on key decisions already made by EPA. For example, as shown in Figure 3–3, community involvement in the Superfund process does not formally begin until after the government and the responsible parties have completed the RI/FS phase.

More recently, however, the EPA Superfund Community Involvement Program has been advocating greater involvement by the affected communities (EPA 1999b) and has developed updated guidance for community involvement during the remedial investigation and feasibility study process at Superfund sites. It must be remembered that not all PCB-contaminated-sediment sites are Superfund sites, nor is EPA necessarily the lead regulatory agency involved at the site. This factor might make the implementation of a community-involvement plan less consistent. The agency has identified a number of lessons that they have learned about involving the affected community at Superfund sites (see Box 4-4). These lessons emphasize that a more active community-involvement process leads to a risk-management strategy that is more acceptable to a broader cross-section of the community. Table 4–1 illustrates how early and active community involvement can assist in the management process. In addition, several states and other federal regulatory agencies have public participation guidance that encourages strong, active, and early community involvement in various forms of environmental management activities (McLoud et al. 1999; Hance et al. 1988).

|

BOX 4–4 Lessons Learned About Superfund Community Involvement The following is a summary of EPA Superfund staff comments on how community involvement has helped to clean up sites.

Source: Adapted from EPA (1999a). |

The committee is encouraged to see the recent emphasis on community involvement as evidenced by materials on EPA’s Superfund website (EPA 1999a) and recent EPA draft and final guidance (EPA 1999b, 2000). The application of this new emphasis at various sites should, within the framework

TABLE 4–1 A Comparison Between Two Remediation Projects

|

Tacoma (Commencement Bay) |

New York (Hudson River) |

|

Community views might have been divergent (though apparently not exceedingly polarized) at first, but a long, open, consensus-based process with active community participation during the discussion and planning phases led to a more coherent consensus. |

Divergent community views were geographically based. Upper HR—Fewer citizens appeared to support dredging, and more citizens focused on the disruptions of dredging. Lower HR—More citizens appeared to support dredging. More focus on the potential beneficial health and economic outcomes of unrestricted fish consumption. |

|

Citizens demanded and became actively involved in the process early. The citizens obtained the necessary education and technical expertise, and provided science-based opinion to the negotiations. |

Citizens were limited to providing passive feedback at EPA-defined points in the process. Feedback is permitted on nearly completed draft documents and nearly finalized decisions. |

|

Committee Observation: The community-involvement process allowed the citizens to interact with regulators and potentially responsible parties and each other over time. Trust built up as differences were discussed and sorted out, mutual solutions were introduced, and compromises were made. |

Committee Observation: The community-involvement process does not allow the citizens to interact in a fact-based environment, and maintains a divergent community with little communication between the community groups. |

|

Distribution of contamination is relatively small and relatively discrete. |

Widespread contamination is at a relatively high level with continuing leakage of PCBs into the river system. |

|

Highest contamination concentration is moderate (25 parts per million (ppm)). |

Highest contamination concentration is severe (>1,000 ppm). |

|

Community involvement was successful. |

Community involvement was unsuccessful. |

recommended by the committee, result in a more effective process for risk management at PCB-contaminated sites (see Box 4-5)

Traditionally, funding for community-based groups was limited to individual contributions and local fund-raising efforts. In more recent years, community-based organizations have received funding from small local foundations, government grants, and in some instances from private companies. In addition, federal programs now provide funds through the EPA’s Technical Assistance Grants (TAG) for Superfund projects and through environmental justice grants, the Technical Assistance for Public Participation Program (TAPP) for Department of Defense sites, and the Environmental Justice Partnership for Communication grants provided by the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences.

The EPA Technical Assistance Grants program provides $50,000 to grassroots community-based groups so that they can hire their own technical advisor to help community members understand scientific and technical information. As of February 2001, more than 230 TAGs totaling more than $18 million had been issued (Lois Gartner, EPA Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, personal communication to Stephen Lester, Feb. 15, 2001). Although these grants have assisted many community groups, the program has limitations. One problem is that TAGs are not provided early enough in the process. In practice, they have often been awarded after the site management plan has been selected. Other limitations are that they are available only for communities with Superfund sites (Ashford et al. 1991), they cannot be used to evaluate health studies (CHEJ 1990), and only one TAG is permitted per Superfund site.

|

BOX 4–5 Public Participation at the St. Paul Waterway Project The St. Paul Waterway Project in Commencement Bay, Washington State, is an example of the difference that community support can make to the timely and successful completion of a sediment management project. The Tacoma community was consulted early and openly and given a voice in shaping the cleanup strategy to be chosen for the site. They came together early in the process and agreed that capping the contamination in-water was the most cost-effective and environmentally protective solution. With community support, ranging from tribes and environmental groups to labor and industry, Simpson (the company conducting the remediation activities) was able to complete its planning and obtain the necessary construction permits and approvals for the project within less than 2 years. |

The number of TAGs awarded per site is a problem that the committee believes should be addressed. Awarding only one TAG per site might work for a relatively small site, but in situations such as the Hudson River that covers hundreds of miles, it does not. At these large sites, many communities are affected, and their interests and needs might vary greatly. Selecting one group to represent all the voices along a river seems difficult if not impossible. At a minimum, consideration should be given to allowing the broader communities with a diversity of perspectives to have access to the resources they need to participate effectively in any discussions about PCB-contaminated-sediment remediation and management. Another option is to provide more than one TAG per site for sites that cover large areas and have communities with distinctly different interests.

The DOD also awards limited technical assistance funds to communities through the Technical Assistance for Public Participation (TAPP) program that began in 1998. TAPP provides $25,000 to Restoration Advisory Boards (RABs) to obtain technical assistance and enable them to provide more educated feedback about the issues related to remediation of the DOD sites of concern (CPEO 1998).

EPA also supports a Technical Outreach Services to Communities program administered by universities associated with the Hazardous Substances Research Centers (HSRCs). These university research centers are located around the country and offer communities no-cost, non-advocate technical assistance and education on the hazardous substance issues they face. Although these programs cannot serve as advocates for the community, they provide a technical resource to assist community participation in the decision-making process. Additional information can be found by contacting the HSRC program director with the EPA Office of Research and Development or by accessing www.tosc.org.

These programs are included in what EPA terms “building-capacity” programs in communities to increase a community’s knowledge about technical and legal aspects of the management effort, thus making them more effective partners. Building-capacity programs may include seminars and courses about technical aspects or other aspects of a problem or possible solutions, training in the processes used (such as risk assessment), or enabling community access to technical outreach support through such mechanisms as the TAG grants. Even though a building-capacity program increases the knowledge base of the community members, it does not guarantee the community a place at the negotiating table or provide the community with any decision-making power.

Industry is another potential source of funding for community-involvement efforts (see the Asarco Tacoma Smelter case study in Appendix D).

Responsible parties can help provide technical and logistic support for community groups, if asked. Such foundations as the Hudson River Foundation may also assist communities by sponsoring educational seminars and conferences, supporting research on the water bodies, and being involved in educational outreach.

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) funds basic scientific research in areas that may pertain to PCB-contaminated sediments and their management. Three types of centers are supported by NIEHS: (1) 21 environmental health science centers that conduct research on toxicology, epidemiology, occupational health, and prevention and community outreach; (2) five marine and freshwater biomedical sciences centers that focus on the development of alternative marine and freshwater models for toxicological research and the study of human health impacts of seafoodborne toxins; and (3) a developmental center to study health problems of underserved and underrepresented human populations (NIEHS 2001). The community outreach efforts of most of these centers are not designed to deal with the broad range of PCB issues encountered by communities and other affected parties. With time and experience, however, these centers might provide more resources.

Build a Working Relationship with the Community

In a 1996 study of community-involvement programs, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) found that to build an effective working relationship, community involvement should be viewed as a dynamic and developing relationship between community members and agencies and not as something an agency “does to a community.” Community leaders interviewed as part of the ATSDR study emphasized the importance of getting to know citizens as “real people,” seeking community input in designing outreach and education materials, keeping community members updated on new developments, and being forthcoming with information rather than withholding it.

Establish Trust and Respect Between All Parties

Trust and respect are the fundamental underpinnings of a nonadversarial working relationship. Although building trust and mutual respect takes time and may initially slow the decision-making process, the eventual solution is more likely to satisfy all partners and engender less resentment and protest

within and from the affected community. Communities often exhibit an absence of trust in the public trustees (i.e., the regulatory agencies), and a deep mistrust of the PRPs; overcoming this lack of trust can result in a more satisfactory outcome to all parties.

Involve the Community As a Respected Partner

The community needs to be considered a respected partner in the decision-making process. That means affording them respect for their opinions and knowledge—technical, ecological, social, and historical—which may not always mesh with what the regulators and managers “know.” Efforts should be made to create a partnership between all the interested and affected parties. Full partnership in the decision-making process may not always be easy to accomplish, given certain legal and logistic constraints. However, the more the affected community is able to participate in the decision-making process, the more likely they are to accept the outcome, even when the outcome includes some compromise. For example, the current practice of community involvement at most Superfund and RCRA sites brings the community in so late that the government is essentially asking the public to ratify an agency decision rather than asking them for input. As a result, the community is not given a chance to help plan the characterization of a site or evaluate all the possible remediation alternatives.

Empowerment

Successful community involvement requires empowerment of the community representatives by the community and by the other participants in the management and decision-making process. That means that the rest of the participants (the regulatory representatives and the PRPs) must recognize the community as full participants in the process and they must be given the resources to enable their participation.

Communication

Effective communication strategies are critical to the success of a project. Communication must be in a form that people can access, use, and understand. It is important to be aware of and use the languages spoken by the different members of the community; native speakers should be used as

interpreters if necessary. Communication between agencies or government-sponsored entities is also important and can include agencies at different levels of government (local, state, and federal).

Commitment

Involving the community takes a commitment of time and attention on the part of the other parties, especially the regulatory agencies. Involving the public takes time, planning, preparation, and preliminary work to ensure involvement and acceptance by the community and affected public.

Process Transparency

The process must be open and transparent from the start. An open process allows a new person to come into the process at any time. A transparent process makes it clear how decisions are made, what the roles and responsibilities of the participants are, and what information is available, and how it is used in making decisions. Having a historical record that traces decisions, process, and requests from the community as well as providing the facts of the situation will help newcomers become effective participants more quickly. A certain amount of responsibility rests on a new person to learn the history and facts, although it is expected that other involved participants would help in this initiation and training process.

COMMUNITY OUTREACH AND EDUCATION

There will be times when there is little or no apparent community interest at a site and when no grassroots community organization exists. In some places, what seems to be an uninterested community may actually be a community that is not aware of the issue, unclear about the health risks posed by the problem, and unsure about the implications of the existence of the site and of the proposed management plan for themselves and their families. It takes time to develop an awareness of an issue within a community, and it takes time for the community to build activity around the site management effort into their daily schedule.

In these instances, the involved regulatory agencies should take the responsibility for reaching out to the affected community. The extent of necessary outreach and ultimately the level of community involvement, will

depend on the magnitude of the contamination problem, the number of people who are affected, and the interest of community members. According to ATSDR’s study of community-involvement programs, community outreach is most effective when it begins with an effort to learn as much as possible about the community, including its culture, diversity, geography, and political relationships (ATSDR 1996).

Ways to accomplish this effort include prominent placement of public notices and feature articles with meeting and contact information highlighted in the item in commonly read newspapers or local magazines. In communities with a potentially affected non-English-speaking population, these articles and notices should be placed in native language newspapers, radio, and television stations. The non-English notices and articles should be placed early and throughout the process to ensure that the non-English speaking population does not feel disenfranchised and therefore resistant to the outcome.

EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Committee (NEJAC), formed to advise the agency on issues of environmental justice, suggests reviewing correspondence files and media coverage about the site. NEJAC also suggests identifying key individuals who represent different interests in the community and learning as much as possible about these people and their concerns (EPA 1996). This preliminary outreach step can be accomplished by personal contact, telephone, or letters.

Educating the affected community is also a critical part of outreach. To have effective community involvement, the community needs to be educated about the technical, economic, and political aspects of the problem. Studies of community outreach programs have suggested the following guidelines for community education (EPA 1996; ATSDR 1996; CDC 1997; English et al. 1993):

-

Educational materials provided to the community should be culturally sensitive, relevant, and translated when necessary.

-

Materials should be readily accessible, written in a manner that is easy to understand, and timely.

-

Unabridged materials should be placed in accessible repositories, such as public libraries.

-

Meetings should be scheduled to make them accessible and user friendly. They should be held at times that do not conflict with work schedules, dinner hours, and other commitments at facilities that are local and convenient and that represent neutral space, taking into account child-care concerns and time and travel expenses.

-

Meetings should be advertised in a timely manner in the print and electronic media, and notices should provide a phone number and/or address for people to contact about the meeting.

-

Agency staff working on the outreach effort should be trained in cultural, linguistic, and community-outreach techniques.

Education encourages interest in the project, increases everyone’s ability to communicate with each other, helps keep the public involved in the decision-making process, and helps all affected parties set realistic goals for the management project. Education can help the public understand not just the science, but the economics and the physical, chemical, and structural limitations of the remediation options. Education allows the public, who often have historical knowledge of the area, to provide helpful insights into the site, the weather patterns and site responses to the weather, the local environment, and what the habitat was once like and might be like again, if restoration to a similar habitat is a goal of the management project.

Once involved and informed about the project, the community partners should identify their priorities and goals for the process and educate the regulators and other partners about them. Identification of cultural or ethnic priorities or mores might affect what the interested and affected parties of the group think about the project and how they set goals for it.

When steps have been taken to educate the affected parties, ATSDR suggests using a community-guided approach to determine the appropriate level of community involvement. Under this approach, the agency works with community members to develop a community-involvement plan that meets community needs as well as agency requirements. To make this plan work, the agency must view community involvement as a central pillar of its work, not as an add-on (ATSDR 1996).

The community is not the only party that needs to be educated. The regulatory agencies and PRPs also need education. The regulatory agencies may want to increase community participation but not know how or be aware of good risk communication and facilitation techniques. The state and federal agencies should recognize the value of training personnel so that they can become and remain more aware of community needs and issues and learn better ways to work with the affected and interested community groups and individuals.

THE ROLE OF REGULATORY AGENCIES

The state and federal agencies also have a responsibility in the community-involvement process. Agencies need to ensure the existence of institutional memory within the agency. Community members may not always have the time, finances, or ability to stay with the process throughout its duration, and the agencies also change personnel, sometimes frequently. In

that situation, there can be a lack of continuity in personnel and in “memory” of what has happened at the site through the lengthy negotiation or management processes, and resources are wasted as negotiations are repeated about points settled long ago. In addition, site information already obtained (including sampling and tracer information) can be forgotten and lost in the accumulation of documents. Promises made to the community can also be forgotten, as they are made orally all too often at a meeting and not written down.

Agencies (local, federal, and state) can help to ameliorate this problem by requiring a running historical record that continues outside the multitudes of legal and scientific documents that are created during any management process (i.e., beyond the administrative record). This record should be organized and readily accessible and, where possible, available via the Internet and as printed material at local libraries. Most important of all, all promises and commitments made in meetings need to be immediately incorporated into the main section of the time-line, possibly through the use of meeting minutes including action items. This listing of commitments and promises then becomes a point of reference for the communities and the project managers. The creation of such a record must be a high priority for regulatory agencies. The time-line needs to be publicly available from the start and distributed to all meeting participants as well as others who have indicated their interest. The public is thus informed and can provide corrections as needed.

MECHANISMS FOR INVOLVING THE COMMUNITY

A variety of methods are available for involving a community in an open decision-making process. These methods include public meetings and hearings, citizen advisory boards, workshops, citizen surveys, citizen juries and review panels, focus groups, alternative dispute resolution, mediation, and negotiation processes (English et al. 1993; Renn et al. 1995; NRC 1996; Ashford and Rest 1999). Although there is no agreement on the best method, two of the more common methods used are public hearings and meetings and citizen and community advisory boards. Both methods are briefly discussed below.

Public hearings and meetings are the most traditional and familiar form of public participation (Ashford and Rest, 1999). Hearings are often required by law and have been used by agencies to present information and defend their decisions. Public meetings are similar to public hearings in format, but they are not required by law. Hearings and meetings are easy to convene, open to everyone, and provide the opportunity for community members to present their views and possibly affect decisions (NRC 1996). Potential disadvantages include their tendency to occur late in the decision-making

process (NRC 1996) and the possibility that they might be dominated by organized interests, the most outspoken critics in the community, and individuals most at ease with public speaking in the community (Ashford and Rest 1999). The NRC (1996) described public hearings as being best suited for presenting alternative views, information, and concerns and less useful for dealing with imbalances, creating trust, or promoting dialogue. There is rarely a decision or consensus at the end of such meetings, allowing agencies great latitude to ignore any comments and thus create further mistrust.

Community advisory groups are formed at many contaminated sites where there is high community interest. These groups are typically formed to examine one or more issues, provide ongoing advice to an agency or organization, and make recommendations on specific issues (Ashford and Rest 1999). Advisory groups with well-defined charges, adequate resources, and neutrally facilitated processes have been found to have significant policy impacts (Lynn and Busenberg 1995). The NRC (1996) found that advisory groups could overcome many of the deficiencies of public hearings and be extremely productive, if provided the “information that members want, access to appropriate agency personnel, or an independent technical advisor as needed.” They have the advantage of meeting over time, allowing for more in-depth examination of issues, creating relationships, and developing mutual understanding and respect for differing views. Disadvantages are limited inclusiveness and representativeness, a high level of commitment required of members, a need for technical expertise, and questions about whether the agency will use the group’s recommendations (NRC 1996; Ashford and Rest 1999).

Concerns about the make-up of advisory groups, especially those proposed by responsible parties, have been raised (Lewis et al. 1992; Renn et al. 1995). The primary concerns are that members are often hand-picked by the government or institution seeking advice and that membership often consists of all major interested parties, rather than only those who are directly affected by the contamination. Also, unempowered groups and those with views that diverge too far from those of the agency are often excluded, undermining the legitimacy and credibility of the approach (NRC 1996) and providing few opportunities to address issues outside the charge of the group. In those cases, advisory groups are perceived as vehicles for accomplishing a predetermined agenda rather than as mechanisms for facilitating true community involvement.

Several federal agencies use the advisory-group approach. EPA uses citizen advisory groups (CAGs) at Superfund sites with environmental justice concerns (EPA 1995), although the degree to which these groups can influence decision-making appears to be quite small. EPA anticipates that these CAGs “will serve primarily as a means to foster interaction among interested members of an affected community, to exchange facts and information, and

to express individual views of CAG participants while attempting to provide, if possible, consensus recommendations from the CAG to EPA” (EPA 1995).

ATSDR uses citizen advisory panels in conducting health assessments at contaminated sites (ATSDR 1996). The Department of Defense (DOD) uses restoration advisory boards (RABs) in the cleanup of DOD installations (CEQ 1995). RABs are established when (1) installation closure involves the transfer of property to the community; (2) at least 50 citizens petition for an advisory board; (3) the federal, state, or local government requests formation of an advisory board; or (4) the installation determines the need for an advisory board (CEQ 1995).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Risk management of PCB-contaminated sediment sites should include early, active, and continuous involvement of all affected parties and communities as partners. Although the need for involvement of the affected communities has often been recognized, it has not been implemented on a consistent basis. Community-involvement efforts at most PCB-contaminated sediment sites have not been effective. At communities visited by the committee, the committee found an active, involved, and educated public that is eager to participate in the site evaluation and remedy selection process. Despite the presence of a concerned public at these sites, the committee found that the opportunities for public involvement generally had been limited to prescribed times in the cleanup process and that the process was dominated by the PRPs and the agencies with little communication among affected parties. Significant distrust developed at some of these sites among the regulatory agencies and between the regulatory agencies, the site owners, the affected communities, and other interested parties. This distrust led to a gridlock at many sites, with extensive delays or no forthcoming management decision. Involvement by all affected parties in the entire decision-making process may help avoid the gridlock and expedite the management process.

The framework developed by the Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk Management established a critical role for all affected parties by integrating them into the risk management process from the initial problem-definition stage through all of the remaining stages. Community involvement will be more effective and more satisfactory to the community if the community is able to participate in or directly contribute to the decision-making process. Passive feedback about decisions already made by others is not what is referred to as community or stakeholder involvement. The committee’s interpretation of the commission’s report (PCCRARM 1997), and the committee’s site visits and discussions with agency personnel,

industry representatives and community members indicate that passive feedback does not appear to be an effective community-involvement strategy compared with an active participation model.

There are many benefits to community involvement including giving communities a rightful place at the table and in the process, educating the community on the issues, and providing a means for communication and collaboration. Community involvement at PCB-contaminated sediment sites should include representatives of all those who are potentially at risk due to contamination, although special attention should be given to those most at risk. People want to be treated with respect, recognized for their knowledge of their community, and considered equals in the process.

No one strategy for involving the public at PCB-contaminated sediment sites is appropriate in every case. At sites where grassroots organizations formed to address the problem already exist, these groups can provide the basis for public-involvement plans. At other sites, regulators and site owners have a responsibility to educate the affected public and determine the level of interest in participating in the decision-making process.

The affected communities need to be given the resources to effectively participate.

The committee makes the following recommendations for improving the involvement of affected parties at PCB-contaminated-sediment sites:

-

Federal, and state environmental regulations and guidelines for managing contaminated sites that affect communities immediately adjacent to these sites should be changed to allow community involvement as soon as the presence of contamination is confirmed at these sites.

-

The key lessons identified in the 1999 EPA report Lessons Learned from Community Involvement at Superfund Sites should be carefully reviewed by regulatory agencies. The report encourages a more active community role in planning and implementation of a risk-management strategy. The report emphasizes that a more active community-involvement process results in a site-management solution that is more acceptable to a broader cross-section of the community.

-

EPA, state regulators, and responsible parties should ensure that interested community groups can obtain independent technical assistance to help understand the health risks and potential remedies being considered to manage PCB-contaminated-sediment sites. The availability of this assistance should be timely and provided by an objective source.

-

EPA should provide more than one Technical Assistance Grant (TAG) for sites that cover large distances, as is the case with most PCB-contaminated-sediment sites, and have more than one affected community with distinctly different interests. Awarding only one TAG per site might work for

-

a conventional site, but it does not work for situations such as the Hudson River that covers hundreds of miles. In these situations, many communities are affected, and the interests and needs of the different communities might vary greatly.

REFERENCES

Ashford, N.A. 1988. Science and values in the regulatory process. Stat. Sci. 3(3):377–383.

Ashford, N.A., and K.M.Rest. 1999. Public Participation in Contaminated Communities, Center for Technology, Policy, and Industrial Development, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Ashford, N.A., C.Bregman, D.E.Hattis, A.Karmali, C.Schabacker, L.J.Schierow, and C.Whitbeck. 1991. Monitoring the Community for Exposure and Disease: Scientific, Legal, and Ethical Considerations. Center for Technology, Policy, and Industrial Development, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Rep. No. U60/CCU/100929–02. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta, GA.

ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). 1996. Learning from Success: Health Agency Effort to Improve Community Involvement in Communities Affected by Hazardous Waste Sites. Through a cooperative agreement with Boston University School of Public Health and Henry S. Coles & Associates. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta, GA.

Brown, P., and E.J.Mikkelsen. 1997. No Safe Place: Toxic Waste, Leukemia, and Community Action. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

CDC (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1997. Principles of Community Engagement. Committee on Community Engagement, Office of Public Health and Science, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

CHEJ (Center for Health, Environment & Justice). 1990. Report on a Meeting Between ATSDR and Community Representatives, Washington. DC. June 30.

CEQ (Council of Environmental Quality). 1995. Improving Federal Facilities Cleanup: A Report of the Federal Facilities Policy Group. Council of Environmental Quality, Office of Management and Budget, Washington, DC. October.

Chess, C., and K.Purcell. 1999. Public participation and the environment: Do we know what works? Environ. Sci. Technol. 33(16):2685–2692.

CPEO (Center for Public Environmental Oversight). 1998. Report of the National Stakeholders Forum on Monitored Natural Attenuation. Center for Public Environmental Oversight, San Francisco Urban Institute, San Francisco State University. October. [Online]. Available: http://www.cpeo/org/pubs/narpthtml.

Dowie, M. 1995. Losing Ground, American Environmentalism at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Eden, S. 1996. Public participation in environmental policy: considering scientific, counter-scientific and non-scientific contributions. Public Understand. Sci. 5(3):183–204.

Edelstein, M.R. 1988. Contaminated Communities: the Social and Psychological Impacts of Residential Toxic Exposure. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Edelstein, M.R. 1993. When the honeymoon is over: environmental stigma and distrust in the siting of a hazardous waste disposal facility in Niagara Falls, New York. Research in Social Problems and Public Policy 5:75–95.

English, M.R., D.Counce-Brown et all. 1991. The Superfund Process: Site-Level Experience. Knoxville, TN: Waste Management Research and Education Institute.

English, M.R., A.K.Gibson, D.L.Feldman, and B.E.Tonn. 1993. Stakeholder Involvement: Open Processes for Researching Decisions About the Future Uses of Contaminated Sites. Waste Management Research and Education Institute, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. September.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1992. Community Relations in Superfund: A Handbook. EPA/540/R-92/009. OSWER 9230.0–03C. PB92–963341. Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. January.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1995. Guidance for Community Advisory Groups at Superfund Sites. EPA 540-R-94–063. OSWER-9230.0–28. Office of Emergency and Remedial Response, Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC. December.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1996. The Model Plan for Public Participation. EPA 300-K-96–003. Public Participation and Accountability Subcommittee, National Environmental Justice Advisory Council, Office of Environmental Justice. November.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1999a. Lessons Learned about Superfund Community Involvement, Features Partnerships at Waste Inc, Superfund Site, Michigan City, Indiana. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 5.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 1999b. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund: Vol. 1. Human Health Evaluation Manual Supplement to Part A: Community Involvement in Superfund Risk Assessments. EPA 540-R-98–042.. OSWER 9285.7–01E-P. PB99–963303. Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, Washington, DC. [Online]. Available: http://www.epa.gov/oerrpage/superfund/programs/risk/ragsa/ci_ra.pdf. March.

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.). 2000. Draft Public Involvement Policy. Fed. Regist. 65(250):82335–82345. (December 28, 2000).

Gibbs, L.M. 1998. Love Canal: The Story Continues… Stoney Creek, CT: New Society Pub.

Gottlieb, R. 1993. Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Fiorino, D.J. 1989. Environmental risk and democratic process: a critical review. Columbian Journal of Environmental Law 14:501–547.

Fiorino, D.J. 1990. Citizen participation and environmental risk: a survey of institutional mechanisms. Science, Technology and Human Values 15(2):226–243.

Folk, E. 1991. Public participation in the Superfund cleanup process. Ecology Law Quarterly 18(1):173–221.

Hance, B.J., C.Chess, and P.M.Sandman. 1988. Improving Dialogue with Communities: A Risk Communication Manual for Government, Environmental Communication Research Program, New Jersey Agricultural Experimental Station. Trenton, NJ: Division of Science and Research.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1998. Toward Environmental Justice: Research, Education, and Health Policy Needs. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kasperson, R.E. 1986. Six propositions on public participation and their relevance for risk communication. Risk Anal. 6(4):275–281.

Kunreuther, H., K.Fitzgerald, and T.Aarts. 1993. Siting noxious facilities: a test of the facility siting credo. Risk Anal. 13(3):301–318.

Lewis, S.J. et al. 1992. The Good Neighbor Handbook. A Community-based Strategy for Sustainable Industry. Waverly, Mass: Good Neighbor Project.

Lynn, F.M. 1988. Citizen Involvement in Hazardous Waste Sites: Two North Carolina Success Stories. Environmental Impact Assessment and Review 7(4):347–361.

Lynn, F.M. and G.J.Busenberg. 1995. Citizen advisory committees and environmental policy What we know, what’s left to discover. Risk Anal. 15(2):147–162.

McCallum, D.B., S.L.Hammond, and V.T.Covello. 1991. Communicating about environmental risks: how the public uses and perceives information sources. Health Education Quarterly 18(3):349–361.

McLoud, S., H.Stanbrough, and C.Stern, eds. 1999. Watershed Action Guide for Indiana, IDEM Watershed Management Section. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM). [Online]. Available: http://www.state.in.us/idem/owm/planbr/wsm/. (Feb. 20, 2001)

Mitchell, J.V. 1992. Perception of risk and credibility at toxic sites. Risk Anal. NIEHS (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences). 2001. Community Outreach and Education Program (COEP). [Online}. Available: http://www.niehs.nih.gov/centers/coep/coepcver.htm (Last updated July 27, 2000).

NRC (National Research Council). 1992. Assessment of the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Studies Program: III. Social and Economic Studies. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 164 pp.

NRC (National Research Council). 1996. Understanding Risk, Informing Decisions in a Democratic Society, P.C.Stern and H.V.Fineberg, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 264 pp.

NRC (National Research Council). 2000. Natural Attenuation for Groundwater Remediation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 292 pp.

Nelkin, D. 1975. The political impact of technical expertise. Social Stud. Sci. 5:34–54.

O’Brien, M. 2000. Making Better Environmental Decisions, An Alternative to Risk Assessment. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 286 pp.

Ozonoff, D., and L.I.Boden. 1987. Truth and consequences: health agency responses to environmental health problems. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 12(3&4): 70–77.

PCCRARM (Presidential/Congressional Commission on Risk Assessment and Risk

Management). 1997. Framework for Environmental Health Risk Management: Final Report. Washington, DC: The Commission.

Renn, O., T.Webler, and P.Wiedemann. 1995. A need for discourse on citizen participation: Objectives and structure of the book. Pp. 1–16 in Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation: Evaluating Models for Environmental Discourse. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Rich, R.C., M.Edelstein, W.K.Hallman, and A.H.Wandersman. 1995. Citizen participation and empowerment: the case of local environmental hazards. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23(5):657–676.

Sexton, K., K.Olden, and B.Johnson. 1993. “Environmental Justice”: the central role of research in establishing a credible scientific foundation for informed decision making. Toxicol. Ind. Health 9(5):685–728.

Unger, D.G., A.Wandersman, and W.Hallman. 1992. Living near a hazardous waste facility: Coping with individual and family distress. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 62(1):55–70.

Yosie, T.F., and T.D.Herbst. 1998. Using Stakeholder Processes in Environmental Decision-Making. An Evaluation of Lessons Learned, Key Issues, and Future Challenges. Washington, DC: Ruder Finn.