1

Introduction

The Upper Mississippi River–Illinois Waterway (UMR–IWW) is an important component of the U.S. inland navigation system. Only the Lower Mississippi River and the Ohio River carry more barge traffic. Commercial barge traffic on the Upper Mississippi carries grain from the U.S. Corn Belt region downstream to New Orleans, where it is then shipped to international markets. Other commercial cargo shipped on the Upper Mississippi is mainly fertilizer (upstream), coal (both upstream and downstream), and petroleum. In 1995, 126 million tons of cargo were shipped on the UMR–IWW system (USACE, 1995).

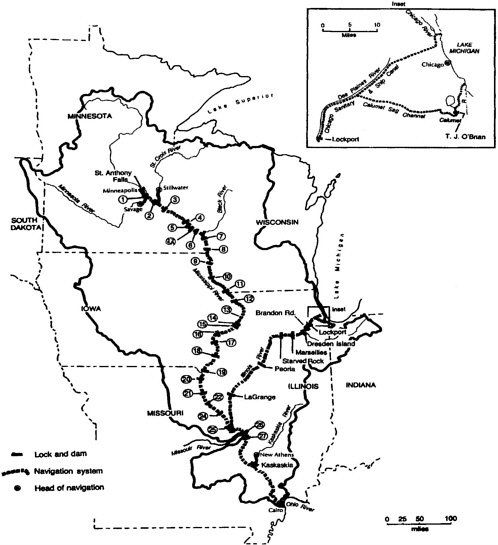

The central feature of this navigation system is 29 locks and dams on the Upper Mississippi River that help maintain a permanent 9-foot channel for barge traffic ( Figure 1.1 ). These locks and dams were constructed and are operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE, or Corps). In addition to these locks and dams, the Corps is responsible for the construction, operation, and maintenance of a variety of river channel training structures and activities on the UMR–IWW, including wing dams, revetments, and dredging.

In 1989, the Corps initiated investigations to determine the economic viability of extending locks on the lower portion of the Upper Mississippi River. Many of the locks and dams were constructed in the 1930s and were originally designed for tows up to 600 feet long. Since then, the length of a typical tow has doubled, and the volume of river traffic has increased significantly. Increases in the congestion of river traffic resulted in calls from the shipping and grain industries for the extension of locks to help alleviate the congestion. The Corps initiated the feasibility study of the system to determine if the extension of several locks on the lower portion of the UMR –IWW system would be economically justifiable.

In an inland navigation study, the Corps must consider a variety of economic, engineering, and environmental factors; sophisticated analytical techniques are used to estimate demand, cost, and environmental consequences. The Corps typically conducts its water resources project planning studies for individual, site-specific water resources projects. This study, however, considered the entire Upper Mississippi River –Illinois Waterway navigation system and is among the larger system-wide studies the Corps has conducted.

Before the study was completed, controversies arose over the Corps ' assumptions and methods employed in the economics portion of the study. To assess the integrity of the Corps' study, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) requested the National Academies to conduct a review of the Corps' Upper Mississippi River–Illinois Waterway system navigation feasibility study.

UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER NAVIGATION

The Corps' navigation-enhancement activities on the Upper Mississippi River date back to the nineteenth century. In 1864, the U.S. Congress authorized the first system-wide project to improve the river for navigation by providing a 4-foot channel. Because of limitations in project funding and scope, the Corps made few changes to the river, and navigation continued to be hindered by river snags, overhanging trees, and a shifting river channel. In 1878, Congress authorized a 4.5-foot navigation channel project for the Upper Mississippi. This was during a period of significant growth in population and in agricultural production in the region, and the navigation project was initiated partly in response to the threat of a bulk shipping monopoly by the railroads. From the 1870s to the first decade of the twentieth century, timber (especially white pine) was the most important commodity moved on the Upper Mississippi (Anfinson, 1996). By roughly 1910, however, the importance of timber fell as the white pine forests of western Wisconsin and northern Minnesota were depleted, leaving the Upper Mississippi River with no important commodity. The early twentieth century also saw the decline of steamboat traffic on the river, and railroads were carrying a larger share of grain and passenger traffic.

Nonetheless, Congress authorized a 6-foot navigation channel project in 1907, and the Corps began building more wing dams and adding to the existing ones. These wing dams, which extend into the river from the main shoreline or from the bank of an island, were intended to narrow the river and constrict its flow into the main navigation channel. But there was little river traffic in the 6-foot channel. In fact, as Anfinson (1993) states, “By 1918, no through traffic moved between St. Paul and St. Louis.” In 1922, the Interstate Commerce Commission declared “Water competition on the Mississippi River north of St. Louis is no longer recognized as a controlling force but is little more than potential” (cited in Anfinson, 1996).

Boosters of navigation fought strongly to restore commercial shipping on the Mississippi River. Despite a “thirty-year decline in traffic on the upper river” (Anfinson, 1993), in 1930 Congress included a 9-foot-channel project in the 1930 Rivers and Harbors Act. Under this project, the Corps of Engineers constructed Locks and Dams 3 (Red Wing, Minnesota) through 26 (Alton, Illinois), joining completed structures at Keokuk, Iowa (1913), St. Paul, Minnesota (1917), and Hastings, Minnesota (1930).

The 9-foot channel-project represented a turning point in Upper Mississippi River history. Previous efforts at deepening the river's channel focused on narrowing the channel through dredging, wing dams, and closing dams (which ran from one shore to an island, or between islands, to divert flows from backwaters and side channels into the main channel). The locks and dams constructed to help create the 9-foot navigation channel, in contrast, created a series of navigation pools, significantly changing river commerce and ecology (Anfinson, 1993):

With the nine-foot channel project, the Corps initiated a completely new approach to navigation improvement. The locks and dams would widen and deepen the river, slowing its pace. In doing so, the Corps would create a more reliable navigation channel and enable shippers to match or exceed the economies of scale enjoyed by railroads. The wider, deeper, and slower-moving channel would affect the river' s ecosystems in ways far different from channel constriction.

In 1940, the Corps completed the 9-foot channel project. Twenty-six locks and dams now crossed the Upper Mississippi between Minneapolis and Alton. Lower and Upper St. Anthony Falls locks and dams were completed in 1956 and 1963, respectively, and Lock and Dam 27 (Granite City, Illinois) was completed in 1964, bringing the total to 29.

Commercial navigation on the Upper Mississippi grew substantially following completion of the 9-foot project, increasing to 126 million tons per year by 1995 (USACE, 1995). But the navigation-enhancement projects on the Upper Mississippi River, as well as other river training activities and barge traffic, have had negative ecological side effects. Congress has often been at the center of discussions regarding the appropriate balance between navigation and river training activities, and environmental conservation. An example of congressional efforts to accommodate both navigation and environmental interests is in the 1986 Water Resources Development Act (WRDA), in which Congress declared the Upper Mississippi River system “a nationally significant ecosystem and a nationally significant commercial navigation system ” (WRDA 1986; Public Law 99-662). As part of this act, the Environmental Management Program (EMP) was established. The EMP oversees long-term ecological monitoring on the Upper Mississippi River, and it plans and constructs fish and wildlife habitat restoration projects. The current federal agencies with responsibilities in the EMP are the Corps (planning, design, construction, and monitoring of habitat restoration projects), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (lead coordination responsibility and other duties), and the U.S. Geological Survey (long-term ecosystem monitoring). In addition to the EMP, Congress also authorized construction of a second lock at Lock and Dam 26 at Alton, Illinois, as part of the 1986 WRDA.

NAVIGATION SYSTEM FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE WATERWAY SYSTEM

Initial investigations regarding potential expansion of waterway capacity on the Upper Mississippi River and Illinois Waterway were conducted in the late 1980s. Corps of Engineers' planning studies are conducted by the Corps' district offices in two phases: reconnaissance and feasibility. Reconnaissance studies are conducted to determine if there is federal interest in a water resources problem or opportunity. Reconnaissance studies today are to be conducted in no more than one year, are to cost no more than $100,000, and are fully funded by the federal government. A reconnaissance study ends with a recommendation to either halt the planning efforts or to proceed to the feasibility study stage.

Feasibility studies are cost-shared with a local sponsor and are conducted to formulate alternative approaches (e.g., structural, nonstructural) and alternative design characteristics (e.g,

different materials that could be used for a flood damage reduction levee, or different levee heights). Among these alternatives, the Corps is mandated to include an economically optimal alternative, the National Economic Development (NED) plan. Once a range of alternatives is identified, the Corps generally convenes an Alternative Formulation Briefing (AFB) for study sponsors, interested groups, and the public. When the study sponsor and the Corps agree on a final plan, the feasibility study is signed by the Corps' division office engineer, signifying that the Corps' field-level office approves of the project. The feasibility study is then submitted to Corps' Headquarters (HQ) in Washington, D.C. for review. The Washington-level review is the first level of formal study review beyond the district office.

The review at Corps Headquarters is conducted by Corps engineering and technical staff. If the feasibility study is approved by Corps Headquarters, the study is forwarded to the Corps' Chief of Engineers for final approval. The approval from the Chief of Engineers results in a “Chief's Report,” which is forwarded to the Office of Management and Budget for inclusion in the president's budget (for more detailed discussion of the Corps's water resources planning procedures, see NRC, 1999a).

In May 1988, the Corps' Rock Island district office developed an initial appraisal regarding possible expansions on the waterway. In August 1989, the Rock Island district office completed a Plan of Study (POS) for the UMR–IWW navigation studies. The Corps' Plan of Study (USACE, 1991) recommended two separate navigation reconnaissance studies for investigating potential navigation improvements. Following this recommendation, separate reconnaissance studies were conducted for the Illinois Waterway and the Upper Mississippi River. The three-volume reconnaissance report for the Illinois Waterway was completed in October 1990, and the two-volume Upper Mississippi River reconnaissance report was completed in June 1991. Both reports recommended more detailed systematic analysis of environmental, engineering, and economic issues so that a system wide study of the navigation system could be developed (USACE, 2000a).

In October 1991, Corps of Engineers Headquarters directed that the two studies be combined into one feasibility study providing a systems approach to addressing navigation issues. Staff members from the (then) North Central and Lower Mississippi Valley Divisions of the Corps, and from its St. Paul, Rock Island, and St. Louis district offices, developed a strategy for conducting the feasibility study. In 1997, the Corps reorganized its division offices, and these three district offices became part of the Corps' new Mississippi Valley Division (along with Corps district offices in Memphis, New Orleans, and Vicksburg). Staff from the New Orleans district office of the Corps also joined the study group.

The Corps' navigation feasibility study of the Upper Mississippi River and Illinois Waterway system was initiated in April 1993. This feasibility study followed a Corps reconnaissance study that indicated the potential need for immediate improvements at several locks and dams and future improvements at others. The Corps stated that “the principal problem being addressed is the potential for significant traffic delays on the system within the 50-year planning horizon, delays that will result in economic losses to the Nation” (USACE, 2000a).

The study was originally envisioned to be a 6-year effort, but because of its complexity and because of comments from the public and coordinating agencies, some modifications were necessary. For example, in early 1998, it was recognized that some of the environmental, eco-

nomic, and engineering studies were taking longer to complete and review than originally anticipated.

The Corps divided research and planning duties within the study into five groups: economics, engineering, environmental/historic properties, project management/plan formulation, and public involvement. In addition to holding public meetings about the navigation study, the Corps worked with other stakeholders and experts from other federal and state agencies. These groups included a Governors' Liaison Committee —which consisted of governor-appointed representatives from the five Upper Mississippi River basin states (Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin) and the commander of the Corps' Mississippi Valley Division—and the Navigation Environmental Coordination Committee (NECC), which consisted of representatives from the five basin state-level natural resources and conservation agencies.

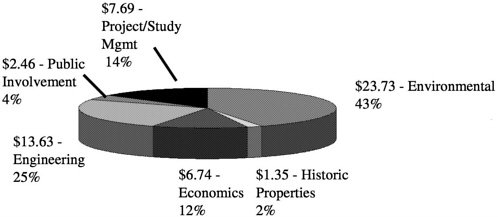

The Corps issued a draft feasibility study report in July 2000 (USACE, 2000a) and was scheduled to release its final report in the second half of 2001. This National Research Council study and report thus reviews and assesses the Corps' draft feasibility study. As of late 2000, the cost of the draft navigation feasibility study was $55.6 million, with the largest percentage (43 percent) of this cost being associated with the environmental analysis ( Figure 1.2 ).

FIGURE 1.2 Feasibility Study Cost Estimate ($ in millions and percent of total).

SOURCE: USACE, 2000a.

CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

In early 2000, the DOD requested the National Academies to review the Corps' Upper Mississippi River–Illinois Waterway navigation system feasibility study. Given the publicity surrounding this study, it was requested that the study be completed relatively quickly. A joint committee of the National Academies' Transportation Research Board (TRB) and Water Science and Technology Board (WSTB) was convened to carry out the study. The charge to the committee is as follows:

This study will focus on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' economic analysis regarding proposed improvements, including economic assumptions, methods. and forecasts regarding barge transportation demand on the Upper Mississippi River-Illinois Waterway. The Corps must also consider larger water resources project planning issues, such as formal U.S. federal water resource planning guidelines, possible environmental impacts, and the costs of navigation improvements. Thus, while the committee will focus on the Corps' economic analysis, they will also comment upon the extent to which these larger issues are being appropriately considered in the navigation system feasibility study.

Because the Corps has not yet completed its navigation feasibility study, the committee could not review and comment on the Corps' final navigation feasibility study; the committee, however, reviewed a draft of that study (USACE, 2000a). The committee concluded, and the Department of Defense agreed, that an interim report that reviewed and commented on the Corps' models and methods would be useful. Based on its review of the Corps' methods in the draft report, the committee aims to provide helpful advice to the Corps for completion of the navigation system feasibility study.