Colloquium

Role of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in innate immunity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections

Gerald B. Pier*

Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115-5899

Chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection occurs in 75–90% of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). It is the foremost factor in pulmonary function decline and early mortality. A connection has been made between mutant or missing CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in lung epithelial cell membranes and a failure in innate immunity leading to initiation of P. aeruginosa infection. Epithelial cells use CFTR as a receptor for internalization of P. aeruginosa via endocytosis and subsequent removal of bacteria from the airway. In the absence of functional CFTR, this interaction does not occur, allowing for increased bacterial loads in the lungs. Binding occurs between the outer core of the bacterial lipopolysaccharide and amino acids 108–117 in the first predicted extracellular domain of CFTR. In experimentally infected mice, inhibiting CFTR-mediated endocytosis of P. aeruginosa by inclusion in the bacterial inoculum of either free bacterial lipopolysaccharide or CFTR peptide 108–117 resulted in increased bacterial counts in the lungs. CFTR is also a receptor on gastrointestinal epithelial cells for Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the etiologic agent of typhoid fever. There was a significant decrease in translocation of this organism to the gastrointestinal submucosa in transgenic mice that are heterozygous carriers of a mutant ∆F508 CFTR allele, suggesting heterozygous CFTR carriers may have increased resistance to typhoid fever. The identification of CFTR as a receptor for bacterial pathogens could underlie the biology of CF lung disease and be the basis for the heterozygote advantage for carriers of mutant alleles of CFTR.

N either novices nor experts dispute the complexity of the immune system. A multitude of physiologic, cellular, and molecular factors work together to identify foreign antigens (particularly of the harmful microbial variety), respond to them, and eliminate them. Responses start almost immediately after contact, and during the earliest phases of infection, mammals rely on the innate immune system to rid themselves of harmful microbes. Fortunately, this system works efficiently most of the time; however, susceptibility to serious microbial infection increases when breakdowns occur in this system. Compromising key innate immune factors such as the physical barrier of skin (e.g., as a result of severe wounds or trauma), disruption of mucosal barriers (e.g., by injury, chemotherapy, or radiation), or acquired or induced suppression of phagocytic cell function all lead to markedly enhanced rates of microbial infection, particularly with bacterial pathogens.

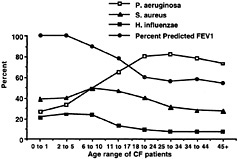

Among the more puzzling failures of the innate immune system are the ones associated with defects in the gene encoding the cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), leading to chronic lung infection with an unusual variant of the ubiquitous Gram-negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Over 80% of patients with CF acquire a P. aeruginosa infection that results in progressive loss of lung function and early death (Fig. 1). The initially acquired strain is typically an environmental isolate (1) that expresses a smooth lipopolysaccharide (LPS) containing O side chains and little or no extracellular mucoid exopolysaccharide (alginate). After an indeterminate—but probably short—time, the organism phenotypically changes to an LPS-rough (i.e., lacking O side chains), mucoid exopolysaccharide-hyperexpressing (i.e., mucoid) variant. These changes are correlated with an acceleration in the decline in lung function in patients with CF (2, 3). The challenge in connecting innate immunity at mucosal surfaces with the clinical aspects of CF is to explain how defects in a chloride ion channel lead to such a high level of infection with one predominant microbial pathogen.

CF

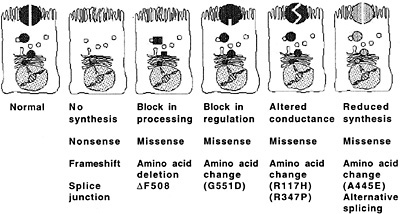

CF arises from mutations in the gene encoding CFTR (4, 5), a plasma membrane protein involved in chloride ion secretion ( 6) and regulation of other ion channels (7). The consequences of these mutations at the protein level are varied, given that hundreds of different mutations in CFTR (898 as of April 2000) have been reported. The ∆F508 CFTR allele, which results from an in-frame 3-bp deletion in the CFTR gene and the subsequent loss of a phenylalanine at position 508, accounts for two-thirds of all mutant CFTR alleles. About one-half of patients with CF are homozygous for this genotype. In general, nonsense or stop mutations in CFTR result in severe disease because of a lack of plasma-membrane CFTR. The ∆F508 CFTR allele gives rise to a misfolded protein that does not make it out of the endoplasmic reticulum and is degraded in cytoplasmic proteosomes after multiubiquitination.

Some mutations associated with severe disease nonetheless give rise to a mutant protein in the membrane, but the mutant protein cannot properly mediate chloride ion conductance and perhaps other critical functions of CFTR. Before modern medical management of this disease, the major clinical manifestations of CF occurred in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and intestinal blockade and malnutrition were prominent factors in death before 1 year of age. As might be expected, there is high-level expression of CFTR in the GI epithelium, principally in the crypts. For the past 30–40 years, the GI symptoms have been managed adequately, and the major clinical problem for patients with CF has been progressive loss of pulmonary function over many years caused by chronic bacterial infection with

This paper was presented at the National Academy of Sciences colloquium “Virulence and Defense in Host–Pathogen Interactions: Common Features Between Plants and Animals, ” held December 9–11, 1999, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA.

Abbreviations: CF, cystic fibrosis; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; ASL, airway surface liquid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; GI, gastrointestinal.

|

* |

E-mail: gpier@channing.harvard.edu. |

Fig. 1. Inverse relationship between isolation of mucoid P. aeruginosa (but not Staphylococcus aureus or Haemophilus influenzae) and decline in percentage of predicted FEV1, as compiled from the CF Foundation Patient Registry database for 1998.

mucoid P. aeruginosa (4, 5, 8). Thus, the molecular and cellular connections between lung infection and defects in CFTR have been of great interest as the primary determinant of the overall clinical status of patients with CF.

Microbial Aspects of Lung Infection in CF

Despite a complex sputum bacteriology, the progressive decline in pulmonary function that is the hallmark of CF is mostly attributable to a single pathogen, mucoid P. aeruginosa (8). Patients with CF become colonized and sometimes infected with a variety of potential pathogens; S. aureus and nontypable H. influenzae, for example, are common bacterial isolates with pathogenic potential from cultures of CF respiratory tract secretions (Fig. 1). However, there are no compelling data that indicate that either S. aureus or H. influenzae contributes to lung function decline in CF except on the rare occasions when they cause acute pneumonia, empyema, or a similar infection. Indeed, it remains to be determined whether antistaphylococcal therapy in patients with CF confers clinical benefit or harm (9). One unpublished but completed clinical trial of daily antistaphylococcal therapy found no clinical benefit from potent suppression of S. aureus carriage in CF respiratory secretions (H. Stutman, unpublished work). Often after prolonged mucoid P. aeruginosa infection, patients with CF become superinfected with organisms such as Burkholderia cepacia, Aspergillus spp., and atypical mycobacteria (8, 10). In rare instances, patients become infected with virulent microbial pathogens in the absence of P. aeruginosa. Any microbial pathogen can potentially cause serious infection in patients with CF, but only mucoid P. aeruginosa appreciably contributes to the characteristic chronic and progressive decline in pulmonary function (Fig. 1). Studies clearly show that patients with CF harboring only nonmucoid P. aeruginosa and S. aureus maintain >80% of their predicted lung function (2, 3) and that the presence of S. aureus in the absence of mucoid P. aeruginosa actually predicts long-term survival for patients with CF (11).

Fig. 2. Molecular consequences of CFTR mutations. [Reproduced with permission from ref. 17 (Copyright 1995, Lap Chee Tsui)].

The reason that patients with CF initially acquire and fail to eliminate environmental strains of P. aeruginosa is enigmatic. Patients with CF have normal immune function, and the relationship between defects in chloride ion conductance of mutant CFTR and hypersusceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection is not fully elucidated. Recent work supports the idea that, starting at an early age, many patients with CF harbor microbial pathogens in their lungs that can be detected only by invasive techniques such as bronchoalveolar lavage; thus, it may be difficult to know exactly when infection is initiated (12, 13 and 14). Infecting strains of P. aeruginosa do seem to be fairly stable, and most patients harbor a single major clone of P. aeruginosa for many years (15, 16). Little is known about how this otherwise virulent and highly immunogenic pathogen establishes a low-level infection that fails to elicit an appropriate host response leading to prompt bacterial elimination. It is not unreasonable to consider that patients with CF may, in fact, respond to and eliminate many strains of P. aeruginosa until some combination of factors interferes with elimination of one particular strain and chronic infection is initiated. It is not known when the switch to the LPS-rough, mucoid phenotype occurs; however, this change may take place quite early after the initial infection, inasmuch as most patients harbor the nonmucoid phenotype for short periods and the mucoid phenotype for years (1).

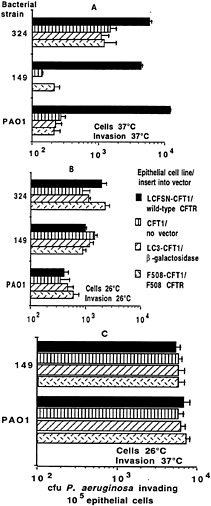

Fig. 3. Invasion of transformed airway epithelial cell lines by three strains of P. aeruginosa (two clinical isolates from patients with CF, 324 and 149, and a laboratory strain, PAO1). Cells were grown for 72 h at the temperature indicated in each figure (“Cells”). Bacteria were allowed to invade the epithelial cells for 3 or 4 h at the temperature indicated by “Invasion ” on the figures. Bars indicate the means of the determinations, and error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. (A) Cells grown at 37°C, a temperature that inhibits membrane expression of ∆F508 CFTR (44); the invasion assay was carried out for 4 h at 37°C. Ingestion of P. aeruginosa by cells expressing wild-type CFTR was significantly higher than in cells lacking wild-type CFTR (P < 0.01, ANOVA). (B) Cells grown at 26°C and invasion assessed at 26°C. (C) Cells grown at 26°C and invasion assessed at 37°C. In both assays where cells were grown at 26°C to promote surface expression of ∆F508 CFTR (44), there were no significant differences (P > 0.2, ANOVA) in bacterial invasion among the cell lines for any P. aeruginosa strain tested.

CFTR and Initiation of P. aeruginosa Infection

The consequences of mutations in the CFTR gene to the production of CFTR protein vary widely because of the multitude of mutations in this gene (Fig. 2, originally published in ref.17). Most—but not all (18)—of the mutations that lead to severe pulmonary disease result in a lack of CFTR protein in the plasma membrane. Because the principal function of CFTR identified to date has been as a chloride ion channel, many of the recent theories connecting loss of CFTR protein in the apical membrane of airway cells with chronic bacterial infections have invoked disruption of airway fluid composition subsequent to decreased transport of chloride ions as a primary mechanism leading to lung infections. For example, Smith et al. (19) proposed that defective chloride ion transport might lead to an increased NaCl content of airway surface liquid (ASL) and that elevated levels of NaCl might interfere with a putative antimicrobial factor present in the airways of both healthy persons and patients with CF. However, the principal antibacterial factors in ASL isolated by this group turned out to be lysozyme and lactoferrin (20). The antimicrobial activity of individual factors was inhibited at high ionic strengths, but this effect, in turn, was overcome with increased concentrations of lysozyme and lactoferrin. Goldman et al. (21) identified a salt-sensitive human β-defensin in the lung that could be compromised in CF if the ASL was hypertonic. However, an elevated salt content in the ASL of patients with CF was not seen in studies by Knowles and colleagues (22), nor was this elevated salt content seen in tracheal xenografts from CF fetuses grown in the flanks of immunodeficient mice (23, 24). Boucher and colleagues (25) proposed that the CF airway epithelia had abnormal levels of fluid adsorption and were actually dehydrated and less able to clear microbes because of loss of mucus transport. Whether nonfunctional antimicrobial constituents of the ASL or increased viscosity may contribute to hypersusceptibility of patients with CF to infection has not yet been tested in animal models or clinical trials. Although disruptions to the normal composition and/or physiologic function of ASL could clearly be a component of the pathology of lung infection in CF, the lack of specificity for P. aeruginosa of these components of innate immunity leaves a gap in our understanding of why most patients with CF are chronically infected by this one bacterial pathogen.

It has also been suggested that increased adherence of P. aeruginosa to airway epithelial cells is a critical component for the initiation of infection in patients with CF (26, 27). The putative receptors are cell-surface residues expressing fucose (28) and asialo GM1 (29); these residues reportedly are more numerous on CF cells (26, 28, 30). Increased asialo GM1 levels have been reported to result from defective organelle acidification that prevents proper addition of neuraminic acid to asialo GM1 residues (31). However, other studies have not confirmed defects in either increased adherence of P. aeruginosa to CF cells (32) or defective cellular physiology (33). In addition, the differences in adherence of P. aeruginosa to CF and non-CF cells is modest; P. aeruginosa is only ≈10–15% more adherent to ∆F508 (FTR homozygous cells) than to normal cells (34). Even if this increased bacterial binding is an accurate reflection of the biology of the CF cells, it does not seem likely that this small difference contributes to the >80% infection rate in CF versus essentially no mucoid P. aeruginosa infection in age-matched, healthy patients. Moreover, increased P. aeruginosa adherence to cells has been observed only when using primary cultures of nasal polyp cells from patients with CF homozygous for the ∆F508 CFTR allele when adherence is compared with that seen with primary respiratory epithelial cell cultures from healthy patients without CF and heterozygous carriers of mutant CFTR alleles (30, 35). Cultured nasal polyp cells from patients with CF who are homozygous for other mutant CFTR alleles did not bind P.

aeruginosa any differently than cells from individuals without CF, but the clinical status of homozygous ∆F508 CFTR patients and that of the patients with CF with other genotypes was indistinguishable (34). A human tracheal epithelial cell line engineered to overproduce the regulatory domain of CFTR also had modestly increased adherence of a single laboratory strain of P. aeruginosa (36), but this cell line is the only non-∆F508 CFTR cell line to have comparable increased binding of P. aeruginosa. It seems difficult to reconcile the finding that increased adherence of P. aeruginosa to epithelial cells early in the course of disease contributes significantly to the onset of infection with the observation that this increased adherence is measured only in cells from patients homozygous for the ∆F508 CFTR allele and a laboratory cell line not representative of any known human CFTR mutation. No in vivo studies in humans or transgenic CF mice have compared the adherence of P. aeruginosa to fucosylated or asialo GM1 receptors on epithelial cells with a CF phenotype to adherence on wild-type cells; thus, the role of binding of P. aeruginosa to these receptors as a component of CF lung disease is predicated only on limited in vitro observations.

Lung Epithelial Cellular Internalization of P. aeruginosa Requires CFTR Binding to Bacterial LPS Core Oligosaccharide

Internalization by epithelial cells may be a mechanism for clearing bacteria from the lung via cellular desquamation of internalized organisms. Other cellular reactions subsequent to ingestion may also modulate the host response to P. aeruginosa on the lung epithelium. Along these lines, Hultgren and colleagues (37) showed that piliated Escherichia coli binds to uroplakins on bladder epithelial cells to initiate infection, and shedding of these cells with bound and internalized organisms promotes their removal. Similar findings for bladder infections were reported by Aronson and colleagues (38, 39 and 40). We have proposed that epithelial cell ingestion of P. aeruginosa may result in cellular desquamation or shedding, with removal of the ingested bacteria from the epithelium, and that ingestion of P. aeruginosa is highly compromised in cells expressing the ∆F508 allele of CFTR compared with that in cells expressing wild-type CFTR (refs.41 and 42; Fig. 3A).

The dependence of efficient P. aeruginosa internalization on intact CFTR expression was documented in a number of studies (41, 42 and 43). The ∆F508 CFTR allele encodes a CFTR protein with a temperature-sensitive defect (44). We found that ingestion of P. aeruginosa by ∆F508 CFTR cells was enhanced by conditions that increased cell-surface expression of the ∆F508 CFTR protein (growth at 26°C; Fig. 3B). When ∆F508 CFTR protein was expressed in the cell plasma membrane, uptake of P. aeruginosa by these airway cells was comparable to uptake by cells expressing wild-type CFTR in the plasma membrane. We then identified the outer-core oligosaccharide of the P. aeruginosa LPS as the bacterial ligand needed for efficient uptake (41). Further studies indicated that CFTR itself is the epithelial cell receptor that binds to P. aeruginosa to promote bacterial internalization (42). Because CFTR is thought to have only a modest number of exposed extracellular loops projecting from the plasma membrane, we investigated whether any of these loops could function as a receptor for P. aeruginosa. We found that amino acids 103–117— and probably only amino acids 108–117, predicted to reside in the first extracellular loop of CFTR—serve as the receptor component for binding and internalization of P. aeruginosa (42). Synthetic CFTR peptide 103–117 and purified P. aeruginosa LPS with a complete-core oligosaccharide bind to each other in a specific fashion (42).

Recent studies have shown that, within a collection of cultured epithelial cells, there is nonhomogeneous expression of CFTR, and expression levels correlate with uptake of P. aeruginosa (45). Using a Madin–Darby canine kidney cell line transfected with a

Fig. 4. Effect of adding inhibitors of the CFTR–P. aeruginosa interaction on the course of infection in neonatal mouse lungs. (A) Addition of LPS core oligosaccharides to the P. aeruginosa challenge inoculum reduces cellular uptake and increases bacterial loads in the lung. Closed circles, no inhibitor; open squares, LPS core oligosaccharide, 10 µg/ml; closed squares, LPS incomplete core oligosaccharide control, 10 µg/ml. Each symbol indicates the median number of bacterial colony-forming units for 8–10 lungs obtained from each group, and the bars indicate the upper and lower quartiles. Differences among groups were analyzed by nonparametric statistics [P < 0.0001; Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric ANOVA; P < 0.001; Dunn procedure for individual pairwise differences between the groups at 1 and 24 h; also at 1 h, the group receiving the incomplete core oligosaccharide had a reduced level (P = 0.05; Dunn procedure) of intracellular bacteria compared with the group receiving nothing along with the inoculum]. At 48 h, the group treated initially with complete-core inhibitor had significantly more bacteria in the lungs (P = 0.003; Kruskal–Wallis; P < 0.05; Dunn procedure for all pairwise comparisons). (B) Effect of addition of synthetic peptides to the bacterial inoculum on P. aeruginosa infection in neonatal mice. (Upper) Amount of P. aeruginosa internalized by lung cells 24 h after infection. (Lower) Total amount of P. aeruginosa found in lungs 24 h after infection. Box plots indicatefrom bottom to top–the 10th, 25th, 50th (median), 75th, and 90th percentiles. Circles above or below the 90th or 10th percentile indicate individual points outside this range. There were 12–14 total lung samples used in each group. For both groups of comparisons (A and B), the overall differences were significant at P < 0.001 (Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric ANOVA test), and the difference between the group receiving the first-domain peptide and the other three groups was significant at P < 0.001 (Dunn procedure for pairwise comparisons).

green fluorescent protein-tagged CFTR (46), we found that cells were distributed into a population that expressed large amounts of CFTR (<10% of the cells; mean fluorescence >100 units), a population expressing intermediate amounts of CFTR (≈40–50% of cells; mean fluorescence about 10 units), and a CFTR-low population (≈40–50% of cells; mean fluorescence <1 unit). The cells with the most CFTR were also the largest in the population, indicating that the increased total amount of CFTR was merely due to the larger volume of these cells. This distribution could be recreated after cell sorting and regrowth of the three subpopulations: the resultant cultures had a distribution in cell size and CFTR protein expression that was close to that of the starting cell population. It seems that the normal state of these cell cultures entails a heterogeneous expression of CFTR protein. When 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride-stained P. aeruginosa organisms were added to the green fluorescent protein-tagged CFTR Madin–Darby canine kidney cells, most of the bacteria were ingested by the cells with modest expression of CFTR, as determined by fluorescent-activated cell sorter analysis. Consistent with the predictions from other experiments, cells with little CFTR took up few P. aeruginosa cells. Although cells with the most CFTR were less able to ingest P. aeruginosa than were cells with modest levels of CFTR, it is hypothesized that these large cells are in a different physiologic state than most of the population, perhaps representative of cells about to enter the mitotic cycle. This hypothesis may account for their low activity in ingesting P. aeruginosa. One implication of these results is that, on a lung mucosal surface, there may be marked local variations in the ability of different cells to ingest P. aeruginosa because of differences in CFTR expression associated with the cells ' underlying physiologic state.

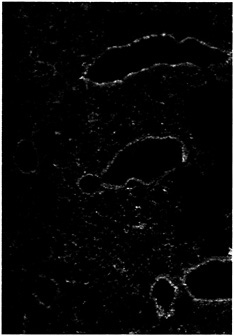

How Does Ingestion of P. aeruginosa Lead to Its Clearance from the Lung?

Because ingestion of P. aeruginosa was compromised severely in cultured cells with the ∆F508 CFTR allele compared with ingestion by cells with at least one wild-type CFTR allele, it could be that reductions in bacterial uptake contribute to the hyper-susceptibility of patients with CF to chronic P. aeruginosa infection. An appropriate animal model to test this hypothesis was needed. Airway epithelial cell uptake of P. aeruginosa in the respiratory tract of a mammal was first described in a neonatal mouse model of lung infection by Prince and colleagues (47). Inoculation of P. aeruginosa onto the nares of neonatal mice normally leads to florid lung inflammation 24 h later, with many P. aeruginosa visualized inside epithelial cells (47). When we used this model, we found that inhibition of cellular ingestion of P. aeruginosa led to increased bacterial burdens in the lung (Fig. 4). In these studies, we could prevent epithelial cell uptake of P. aeruginosa by including with the bacterial inoculum soluble outer-core oligosaccharide from the bacterial LPS (Fig. 4A; ref.41) or the CFTR receptor peptide composed of amino acids 108–117 (Fig. 4B; ref.42). With the synthetic peptide included in the inoculum, there were virtually no intracellular P. aeruginosa organisms in the lungs 24 h after infection (42). Control mice infected with bacteria plus a synthetic peptide corresponding to a scrambled version of CFTR amino acids 108–117 had >104 colony-forming units of P. aeruginosa inside epithelial cells per milligram of lung tissue. Inhibition of CFTR-mediated epithelial cell ingestion of P. aeruginosa in vivo by CFTR peptide 108–117 resulted in a highly significant increase in total bacterial burden in the lungs (median of 105 more colony-forming units of P. aeruginosa per mg of lung tissue). P. aeruginosa infection in mice also produced a dramatic increase in membrane expression of CFTR (Fig. 5), which is normally expressed only at low levels in the absence of P. aeruginosa. Finally, immunogold labeling and electron microscopic visualization showed large amounts of CFTR in the membranes surrounding the bacteria as they entered lung cells in vivo (42). Recent studies in transgenic CF mice with a stop mutation in Cftr (48), a ∆F508 Cftr (49) allele, or a G551D Cftr allele (50) have confirmed the association between decreased lung cell internalization of P. aeruginosa in CF mice and increased bacterial burdens in lung tissue (unpublished data). The fact that transgenic Cftr knockout and G551D mice, both representative of alleles in humans with severe CF, have the same phenotype as ∆F508 Cftr mice indicates that the defect in epithelial cell uptake of P. aeruginosa is not restricted to one allelic variant of Cftr. Thus, internalization of P. aeruginosa may be a critical component of the innate pulmonary defense mechanisms needed for eliminating this pathogen from the respiratory tract.

Fig. 5. Increased expression of CFTR in the bronchial epithelial cells of mice infected with P. aeruginosa. At 1 h after instillation of P. aeruginosa into the lungs of neonatal BALB/c mice, the tissue was removed, fixed, and stained with monoclonal antibody CF3 specific to the first extracellular domain of CFTR (amino acids 103–117; ref.61). Tissue sections stained with an irrelevant control monoclonal antibody had no visible fluorescence (not shown).

CFTR Expression in the Cornea and Its Association with P. aeruginosa Ulcerative Keratitis

Another manifestation of P. aeruginosa infection is corneal ulcerative keratitis, whose incidence is increased by both trauma and use of extended-wear contact lenses (51, 52 and 53). We have demonstrated that cultured corneal cells can ingest P. aeruginosa (54) as can cells on injured corneas during experimental infection ( 55). As with lung cells, the bacterial LPS is the ligand for corneal cell uptake (56), and CFTR is expressed in the cornea and serves as the epithelial cell ligand for ingestion of P. aeruginosa (57). However, unlike the situation in the lung (where surface-exposed airway epithelial cells interact with inhaled P.

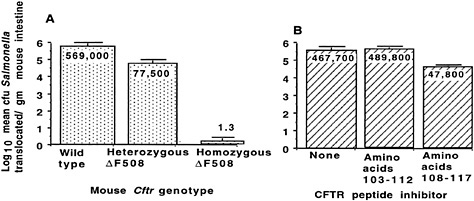

Fig. 6. Translocation of S. enterica serovar Typhi across the Gl epithelium of transgenic ∆F508 CF mice. (A) Decreased translocation of serovar Typhi strain Ty2 from the lumen of the Gl tract of mice with the indicated genotype for murine Cftr. P < 0.001; ANOVA and Fisher probable least square differences for all three pair-wise comparisons. (B) Inhibition of translocation of serovar Typhi strain Ty2 from the Gl lumen of BALB/c mice infected with this bacterium plus a synthetic peptide corresponding to the indicated amino acids in the first predicted extracellular domain of CFTR. P < 0.001; ANOVA and Fisher probable least square differences for pair-wise comparisons between amino acid 108–117 inhibitor and the other two groups. Bars indicate mean of the log10 colony-forming units of serovar Typhi translocated; numbers indicate the antilog of the mean; error bars indicate the SEM.

aeruginosa via CFTR), in the experimental eye infection model, the P. aeruginosa cells are inoculated onto an eye with a deliberate scratch injury, and the bacteria rapidly travel down the scratch to the interface of the bottom layer of epithelial cells and the underlying acellular stroma (55). P. aeruginosa organisms then enter the buried corneal epithelial cells via CFTR-mediated ingestion and are trapped in the lower layers of the corneal epithelium. Unable to shed their burden of internalized bacteria, the buried cells serve as a repository for P. aeruginosa, protecting it from clearance by immune effectors (57). In this instance, ∆F508 CF mice are more resistant than wild-type mice to P. aeruginosa keratitis, and heterozygous mice display an intermediate phenotype (57). Therefore, the consequences of CFTR-mediated ingestion of P. aeruginosa by epithelial cells for the outcome of the infectious process depend heavily on where this encounter takes place. If the cells with internalized P. aeruginosa can clear the organisms from a tissue surface via shedding, then CFTR serves as a major mediator of innate immunity; if not, this process could enhance pathology and worsen disease.

Specificity of CFTR Binding for Other Bacterial Pathogens and Its Consequences in Other Tissues

Among common lung pathogens, CFTR-mediated uptake seems to be specific to P. aeruginosa, and thus, this interaction may be critical for control of the infectious process in the respiratory tract (42). The specificity of CFTR uptake for P. aeruginosa also addresses the issue of why patients with CF overwhelmingly get P. aeruginosa infections and not infections with other pathogens. However, the same region of CFTR that binds P. aeruginosa—amino acids 103–117 in the first predicted extracellular domain—was found also to bind Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and mediate translocation of this enteric pathogen from the GI lumen to the submucosa (58). The consequences are proposed to be 2-fold. At low inocula, serovar Typhi cells that are internalized by GI epithelial cells or that are not ingested at all and remain in the lumen are expelled from the body. At higher doses of serovar Typhi, the desquamation process leaves a hole in the epithelium through which free Salmonella cells can move to the submucosa (59, 60). One implication of this process is that decreased levels of expression of CFTR in the GI epithelium, as might occur in heterozygous carriers of mutant alleles, could result in decreased GI cell ingestion and desquamation with internalized serovar Typhi bacteria and heightened resistance to development of typhoid fever.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we used transgenic CF mice to study translocation of serovar Typhi cells from the GI lumen to the submucosa. In heterozygous ∆F508 Cftr mice, translocation of serovar Typhi cells was reduced by 86% from that in wild-type mice, and essentially no translocation occurred in homozygous ∆F508 Cftr mice (Fig. 6A; ref.58). In addition, including a 10-mer peptide of CFTR, amino acids 108 –117, in an inoculum of serovar Typhi injected into the lumen of wild-type mice reduced the translocation of serovar Typhi cells to the submucosa (Fig. 6B). CFTR bound to the submucosal serovar Typhi cells, as determined by immunoelectron microscopy, and about four times more CFTR was found on serovar Typhi that had translocated into the submucosa of wild-type mice than on translocated organisms in the GI submucosa of heterozygous ∆F508 Cftr mice (42). From this observation, we proposed that the maintenance of the ∆F508 CFTR allele—and perhaps of other mutant CFTR alleles—at high levels (4–5% for ∆F508 CFTR in certain human populations) may be due to increased resistance of heterozygous carriers to typhoid fever.

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate that mutations in CFTR that lead to the presence of nonfunctional or no membrane protein also result in a defect in internalization and clearance of P. aeruginosa from the lung. A similar process may operate on the surface of intact corneal epithelium, but on damaged epithelium, the access of P. aeruginosa to nonsurface epithelial cells, along with the ingestion of organisms via CFTR, actually promotes the pathologic process. For the GI tract, heterozygous carriage of mutant alleles of CFTR may confer increased resistance to typhoid fever by reducing translocation of bacteria from the GI lumen to the submucosa. However, simple ingestion and internalization of bacteria are unlikely to be the entire story. Instead, a complex

process is probably initiated in the epithelial cell when it comes into contact with bacteria, and further cellular activation, cytokine secretion, and inflammation may also contribute to elimination of pathogens from infected mucosa. Moreover, not all mutations in CFTR lead to a loss of membrane protein, and defects in CFTR genes that result in a membrane protein that is nonfunctional with regard to chloride ion secretion may also diminish the protein's ability to orchestrate the full epithelial cell response needed to remove P. aeruginosa from the tissue. The identification of CFTR as a protein that binds P. aeruginosa and coordinates the epithelial cell response leading to bacterial clearance indicates a direct connection between mutant CFTR genes and the clinical course of CF. Thus, in addition to its functions as a chloride ion channel, a regulator of sodium, and perhaps a regulator of other ion channels, CFTR is also a key component in innate immunity on mucosal surfaces, serving as a receptor to ingest and clear microbes and contribute to host resistance to infection.

I thank the following individuals from the Channing Laboratory who carried out the work described in this report: Alev Gerceker, Martha Grout, Kazue Hatano, Jeffrey Lyczak, Gloria Meluleni, and Tanweer Zaidi. Work described in this paper was carried out, in part, under National Institutes of Health Grants AI22535, AI22806, and HL58398 and under a Brigham and Women's Hospital Interdisciplinary Seed Grant.

1. Pier, G. B., DesJardins, D., Aguilar, T., Barnard, M. & Speert, D. P. ( 1986) J. Clin. Microbiol. 24, 189–196.

2. Pedersen, S. S., Hoiby, N., Espersen, F. & Koch, C. ( 1992) Thorax 47, 6–13.

3. Demko, C. A., Byard, P. J. & Davis, P. B. ( 1995) J. Clin. Epidemiol. 48, 1041–1049.

4. Wine, J. J. ( 1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 309–312.

5. Tummler, B. & Kiewitz, C. ( 1999) Mol. Med. Today 5, 351–358.

6. Welsh, M. J., Anderson, M. P., Rich, D. P., Berger, H. A. & Sheppard, D. N. ( 1994) in Chloride Channels, ed. Guggino, W. B. (Academic, San Diego), Vol. 42, pp. 153–171.

7. Stutts, M. J., Canessa, C. M., Olsen, J. C., Hamrick, M., Cohn, J. A., Rossier, B. C. & Boucher, R. C. ( 1995) Science 269, 847–850.

8. Govan, J. R. W. & Deretic, V. ( 1996) Microbiol. Rev. 60, 539–574.

9. McCaffery, K., Olver, R. E., Franklin, M. & Mukhopadhyay, S. ( 1999) Thorax 54, 380–383.

10. Gilligan, P. H. ( 1991) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4, 35–51.

11. Huang, N. N., Schidlow, D. V., Szatrowski, T. H., Palmer, J., Laraya-Cuasay, L. R., Yeung, W., Hardy, K., Quitell, L. & Fiel, S. ( 1987) Am. J. Med. 82, 871–879.

12. Ramsey, B. W., Wentz, K. R., Smith, A. L., Richardson, M., Williams, W. J., Hedges, D. L., Gibson, R., Redding, G. J., Lent, K. & Harris, K. ( 1991) Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 144, 331–337.

13. Abman, S. H., Ogle, J. W., Harbeck, R. J., Butlersimon, N., Hammond, K. B. & Accurso, F. J. ( 1991) J. Pediatr. 119, 211–217.

14. Khan, T. Z., Wagener, J. S., Bost, T., Martinez, J., Accurso, F. J. & Riches, D. W. H. ( 1995) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 151, 1075–1082.

15. Speert, D., Campbell, M., Puterman, M. L., Goven, J., Doherty, C., Hoiby, N., Ojeniyi, B., Lam, J. S., Ogle, J. W., Johnson, Z., et al. ( 1994) J. Infect. Dis. 169, 134–142.

16. Romling, U., Wingender, J., Muller, H. & Tummler, B. ( 1994) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 1734–1738.

17. Zielenski, J. & Tsui, L. C. ( 1995) Annu. Rev. Genet. 29, 777–807.

18. Kerem, E., Reisman, J., Corey, M., Canny, G. J. & Levison, H. ( 1992) N. Engl. J. Med. 326, 1187–1191.

19. Smith, J. J., Travis, S. M., Greenberg, E. P. & Welsh, M. J. ( 1996) Cell 85, 229–236.

20. Travis, S. M., Conway, B. A., Zabner, J., Smith, J. J., Anderson, N. N., Singh, P. K., Greenberg, E. P. & Welsh, M. J. ( 1999) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 20, 872–879.

21. Goldman, M. J., Anderson, G. M., Stolzenberg, E. D., Kari, U. P., Zasloff, M. & Wilson, J. M. ( 1997) Cell 88, 553–560.

22. Knowles, M. R., Robinson, J. M., Wood, R. E., Pue, C. A., Mentz, W. M., Wager, G. C., Gatzy, J. T. & Boucher, R. C. ( 1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2588–2595.

23. Baconnais, S., Tirouvanziam, R., Zahm, J. M., de Bentzmann, S., Peault, B., Balossier, G. & Puchelle, E. ( 1999) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 20, 605–611.

24. Zhang, Y. & Engelhardt, J. F. ( 1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276, C469–C476.

25. Matsui, H., Grubb, B. R., Tarran, R., Randell, S. H., Gatzy, J. T., Davis, C. W. & Boucher, R. C. ( 1998) Cell 95, 1005–1015.

26. Imundo, L., Barasch, J., Prince, A. & Al-Awqati, Q. ( 1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 3019–3023.

27. Prince, A. ( 1992) Microb. Pathog. 13, 251–260.

28. Scanlin, T. F. & Click, M. C. ( 1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1455, 241–253.

29. Comolli, J. C., Waite, L. L., Mostov, K. E. & Engel, J. N. ( 1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 3207–3214.

30. Saiman, L., Cacalano, G., Gruenert, D. & Prince, A. ( 1992) Infect. Immun. 60, 2808–2814.

31. Barasch, J., Kiss, B., Prince, A., Saiman, L., Gruenert, D. & al-Awqati, Q. ( 1991) Nature (London) 352, 70–73.

32. Cervin, M. A., Simpson, D. A., Smith, A. L. & Lory, S. ( 1994) Microb. Pathog. 17, 291–299.

33. Seksek, O., Biwersi, J. & Verkman, A. S. ( 1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 15542– 15548.

34. Zar, H., Saiman, L., Quittell, L. & Prince, A. ( 1995) J. Pediatr. 126, 230–233.

35. Saiman, L. & Prince, A. ( 1993) J. Clin. Invest. 92, 1875–1880.

36. Bryan, R., Kube, D., Perez, A., Davis, P. & Prince, A. ( 1998) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 19, 269–277.

37. Mulvey, M. A., Lopez-Boado, Y. S., Wilson, C. L., Roth, R., Parks, W. C., Heuser, J. & Hultgren, S. J. ( 1998) Science 282, 1494–1497.

38. Aronson, M., Medalia, O., Schori, L., Mirelman, D., Sharon, N. & Ofek, I. ( 1979) J. Infect. Dis. 139, 329–332.

39. Aronson, M., Medalia, O., Amichay, D. & Nativ, O. ( 1988) Infect. Immun. 56, 1615–1617.

40. Dalai, E., Medalia, O., Harari, O. & Aronson, M. ( 1994) Infect. Immun. 62, 5505–5510.

41. Pier, G. B., Grout, M., Zaidi, T. S., Olsen, J. C., Johnson, L. G., Yankaskas, J. R. & Goldberg, J. B. ( 1996) Science 271, 64–67.

42. Pier, G. B., Grout, M. & Zaidi, T. S. ( 1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12088–12093.

43. Pier, G. B., Grout, M., Zaidi, T. S. & Goldberg, J. B. ( 1996) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, S175–S182.

44. Denning, G. M., Anderson, M. P., Amara, J. F., Marshall, J., Smith, A. E. & Welsh, M. J. ( 1992) Nature ( London) 358, 761–764.

45. Gerceker, A. A., Zaidi, T., Marks, P., Golan, D. E. & Pier, G. B. ( 2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 861–870.

46. Moyer, B. D., Loffing-Cueni, D., Loffing, J., Reynolds, D. & Stanton, B. A. ( 1999) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 277, F271–F276.

47. Tang, H., Kays, M. & Prince, A. ( 1995) Infect. Immun. 63, 1278–1285.

48. Zhou, L., Dey, C. R., Wert, S. E., Duvall, M. D., Frizzell, R. A. & Whitsett, J. A. ( 1994) Science 266, 1705–1708.

49. Zeiher, B. G., Eichwald, E., Zabner, J., Smith, J. J., Puga, A. P., Mccray, P. B., Capecchi, M. R., Welsh, M. J. & Thomas, K. R. ( 1995) J. Clin. Invest. 96, 2051–2064.

50. Delaney, S. J., Alton, E. W. F. W., Smith, S. N., Lunn, D. P., Farley, R., Lovelock, P. K., Thomson, S. A., Hume, D. A., Lamb, D., Porteous, D. J., et al. ( 1996) EMBO J. 15, 955–963.

51. Poggio, E. C., Glynn, R. J., Schein, O. D., Seddon, J. M., Shannon, M. J., Scardino, V. A. & Kenyon, K. R. ( 1989) N. Engl. J. Med 321, 779–783.

52. Schein, O. D., Glynn, R. J., Poggio, E. C., Seddon, J. M. & Kenyon, K. R. ( 1989) N. Engl. J. Med. 321, 773–778.

53. Coster, D. J. & Badenoch, P. R. ( 1987) Br. J. Ophthalmol. 71, 96–101.

54. Fleiszig, S. M. J., Zaidi, T. S. & Pier, G. B. ( 1995) Infect. Immun. 63, 4072–4077.

55. Fleiszig, S. M. J., Zaidi, T. S., Fletcher, E. L., Preston, M. J. & Pier, G. B. ( 1994) Infect. Immun. 62, 3485–3493.

56. Zaidi, T. S., Fleiszig, S. M. J., Preston, M. J., Goldberg, J. B. & Pier, G. B. ( 1996) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 37, 976–986.

57. Zaidi, T. S., Lyczak, J., Preston, M. & Pier, G. B. ( 1999) Infect. Immun. 67, 1481–1492.

58. Pier, G. B., Grout, M., Zaidi, T., Meluleni, G., Mueschenborn, S. S., Banting, G., Ratcliff, R., Evans, M. J. & Colledge, W. H. ( 1998) Nature ( London) 392, 79–82.

59. Jones, B. D., Ghori, N. & Falkow, S. ( 1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 15–23.

60. Pascopella, L., Raupach, B., Ghori, N., Monack, D., Falkow, S. & Small, P. L. ( 1995) Infect. Immun. 63, 4329–4335.

61. Walker, J., Watson, J., Holmes, C., Edelman, A. & Banting, G. ( 1995) J. Cell Sci. 108, 2433–2444.