Page 155

5

Intergenerational Transfers

Trends in the ratio of workers to retirees are the tea leaves of policy making for aging populations. Armed with knowledge of age-related behaviors and age-defined benefits in a society, policy makers and commentators alike attempt to read shifts in the relative size of broad age groups for their public policy implications. As more people retire at ever earlier ages, their consumption must come from current output produced by those who work—by either transfer of assets (i.e., claims on output), private/private transfers, or collective wealth schemes (see Thompson, 1998). Of particular concern is whether the well-being of an expanding older population can be secured only at the expense of burgeoning public expenditures (see Chapter 4). Public costs are incurred through a variety of programs providing health care, housing, and financial security for retirees. Whether funded from general tax revenues or mandatory worker contributions, these programs are inherently structured transfers that redistribute resources from workers to elderly nonworkers in a society. Examples of such programs in the United States include Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Comparably structured programs exist throughout Western Europe, Japan, and some other middle-income countries (e.g., Korea, Chile, and Mexico), with variations on the general theme seen in other countries as well (such as Singapore's Central Provident Fund). As noted above, however, publicly funded transfer programs are not the only source of support for the aged, even in developed countries. To varying degrees across societies and over time, the state, the marketplace, and the family have contributed to the support and care of older persons (Lee, 1994b; Soldo and Freedman, 1994).

Page 156

Most of the other chapters in this volume address broad public policy concerns, such as meeting the health care needs of the aged or providing old-age financial security by combining individual savings, market annuities, and public pensions. In a departure from that approach, this chapter focuses on the whole of the family transfer system that disburses privately held resources across generations of kin for many of the same purposes served by public programs. While parents provide children with a range of in-kind services, such as shared food, housing, care services, and financial assistance, both during their lifetime and by bequest, adult children often provide elderly parents with comparable resource transfers. The extent of the latter transfers vary across countries: they are normative throughout Asia (Hermalin, 1997) and Southern Europe (Glaser and Tomassini, 1999); limited and largely responsive to parental health shocks or widowhood in the United States and the United Kingdom (Wolf, 1994a; McGarry and Schoeni, 1999); and rare in Scandinavian countries. 1 Regardless of cultural, institutional, and behavioral differences across countries, however, family transfers, including emotional and affective support, are important to the well-being of older persons.

The demographic forces that give rise to aging populations also transform the structure of the family. With declines in the rates of both fertility and old-age mortality, the number of living generations in a family increases (Watkins et al., 1987) even as the number of same-generation kin declines. In silhouette, the vertically extended family evolves from the pyramid created by regimes of high fertility and mortality to the narrow, elongated family structures observed in developed countries today (Bengtson and Silverstein, 1993). The elongated family structure concentrates obligations for elder care and support among fewer kin in descending generations of a family.

In most countries, the division of labor between the public and family transfer systems is rationalized by long-standing convention, rather than by concerns for efficiency or claims of specialized competency. As a result, interactions between the two broad types of transfer systems define many of the more important policy issues for an aging population. Specifying how transfers from one system affect the flow or volume of resources from the other, however, is seldom straightforward. Increasing inheritance taxes, for example, may “repay” public transfers in the aggre

1In the poorest countries, public transfer programs are rare. Where they exist at all, such benefits are usually restricted to former government workers. Older persons have few options for transferring resources across their own life cycle through private financial markets or participation in private pensions. Surviving adult children are the singular means of insuring against the uncertainties of old age, and family transfers largely determine the well-being of older persons.

Page 157

gate, but over time discourage family care for elderly kin. Alternatively, public care services may prompt a family to redirect its efforts to previously unattended areas of support; for example, adult children may reduce the frequency of their instrumental support but increase their affective support for frail parents. Under this scenario, the parent's overall quality of life might improve, but the net effect for the public sector would be to increase the total volume and cost of publicly financed care services.

Within-country studies can make only limited contributions to a policy agenda focused on the interactions between transfer systems or the efficacy and efficiency of the welfare produced for older persons under a given model. Even the richest of domestic datasets have limited utility for pursuing this agenda. There are several reasons for this. The first, and most obvious, is that with few exceptions (e.g., differences in the generosity of Medicaid benefits across U.S. states), transfer policies within a country are usually standardized. Most national policies dictate, for example, that all workers of a given age from a given sector with comparable work histories receive the same government-funded old-age pension. Cross-national research provides opportunities to relate variations in institutional arrangements to the distribution of attributes that determine benefit eligibility or benefit levels (e.g., sector of employment for government pensions) and the distribution of the old-age welfare produced (e.g., postretirement income security) in a population. In addition, within a given country, the legacy of a unique cultural heritage is imprinted on the division of labor between the state and family transfer systems. Because of this confounding, policy makers cannot reliably anticipate the responsiveness of family transfer behaviors to changes in the design of programs benefiting the older segment of the population.

This chapter considers how inter generational transfer issues frame many of the important public policy questions in both developed and developing countries. We begin by posing a number of policy questions whose answers require novel ways of conceptualizing and producing relevant data. We then view intergenerational transfers from a macroeconomic perspective that focuses on flows of resources between generations. The discussion explores the directionality of wealth flows and considers how they may shift with changes in economic development. The third section addresses measurement issues involved in the collection of data on intergenerational transfers, examining the complexities of kin networks and suggesting which data should optimally be collected. The chapter then examines efforts to model and project family dynamics, including changes in such variables as kin availability, living arrangements, and changing family structures, factors that will assume increasing importance for policy making as societies age. Both micro- and macro-simulation procedures may be useful tools in gauging future policy needs.

Page 158

Next we review research gaps in the area of family transfers, focusing in particular on the benefits and shortcomings of the macro and micro perspectives. Finally, we offer recommendations regarding new data and studies that might permit a synthesis of these two perspectives.

POLICY CONSIDERATIONS

The well-being of older persons depends to a large extent on the content and volume of an intricate set of transfer systems in which people are engaged during their lifetimes. Interactions between public and family transfer systems define many of the important policy issues for aging populations. Yet, as noted earlier, specifying how transfers from one system affect the flow of resources from the other is not straightforward. Along these lines, a number of important policy questions arise.

- 1. Do state-financed programs for the elderly drive out or reduce private/family efforts? If so, at what price to the family or the state? Alternatively, do state transfers magnify the effects of family transfers?

- 2. To what extent does the potential for bequests create incentives for transfers from adult children to elderly parents? In countries with significant disincentives for bequests (e.g., hefty inheritance taxes), are adult child-to-parent transfers of space and time of the same magnitude, prevalence, and duration as in countries where bequests have the potential to repay late-life care and assistance transfers from children? Related to this is the question of whether parental wealth (ownership of land, property, savings) or prior investments in offspring “buy” family support in old age. Does parental wealth create comparable transfer incentives across cultures? To what extent are incentives for children to repay their parents for human capital investment sensitive to tax policies and to state-provided service systems?

- 3. Absent housing constraints, do older persons and their adult children universally buy more household privacy and autonomy as wealth increases? (See Schoeni, 1998.) Does the state implicitly subsidize this preference by producing more in-home services for older persons or bearing the costs of a decaying housing stock?

- 4. What are the full costs of caregiving to the caregiver and to the state? Providing services to elderly parents entails costs, both real and opportunity. These costs are usually estimated very crudely at a point in time with average market wages or replacement costs for a given service. But caregiving also may have longer-term costs that differ across countries. Depending on family leave, job protection, and pension policies, work interruptions for caregiving may not only reduce current wages, but also curtail lifetime earnings and reduce individual savings and accrual rates

Page 159

in pension systems. Does the state eventually absorb the costs of family caregiving through later-life income replacement programs or public services? Alternatively, are the costs of caregiving offset by transfers from other kin to the caregiver (e.g., financial transfers from siblings) or, as Stark (1995) suggests, do caregivers as they age have stronger claims on services from their own children because of “patterning”?

- 5. Are preferences for investing in the human capital of offspring so strong as to thwart policy initiatives to encourage greater savings in midlife or consumption of resources to buy care or financial security in late life? For example, will the modest university fees now being levied in the United Kingdom appreciably reduce savings for old age? To what extent are preferences for human capital investment at the expense of individual consumption or savings culturally determined or responsive to policy? Assuming a constant rate of increase in life expectancy at age 60 or 80 and a continuation of current behavioral parameters, at what age would resource flows from young to old dominate under stylized versions of alternative transfer policies in developed countries?

- 6. How do policies that affect early-life demographic decisions in turn affect late-life behaviors? Demographic regimes and cohort histories imprint on family structure for subsequent decades and are a significant source of variation across countries (Henretta et al., 1997). For individuals, early-life choices ultimately constrain transfer options in later life. Beyond simple structural effects (e.g., childless women have a zero probability of living with offspring, while higher fertility increases the odds of coresidence), the effects of timing factors, such as age at marriage and at first and last birth, may operate through coincident life-cycle staging across generations of a family. Age of offspring at parental retirement, at death of first parent, or at own childbearing may encourage or discourage transfers to elderly parents and affect the magnitude of the transfer. Comparative research on the endogeneity of early-life demographic decisions (e.g., quality of the marriage pool, timing of fertility, childlessness) with late-life transfer outcomes should reveal variations in a range of policy variables within and across countries. A richer understanding of these issues requires a complex research agenda that incorporates distinctions among transfer currencies, providers and provider motivations, and the complete option set for both public and private transfers.

INTERGENERATIONAL TRANSFERS, ECONOMIC WELFARE, AND TRANSFER INSTITUTIONS

Policy makers have an array of options for broadening the resource base that supports older nonworkers. Among these are creating incentives that encourage individuals to transfer more of their own resources

Page 160

from mid- to late life through private savings, increasing the length of work life by penalizing early retirement, and encouraging transfers of financial assistance or help across generations of the family. Each of these options conveys costs and benefits for the elderly individual, his/her family, and the society.

Over the past two decades, economic demographers have developed simple and elegant methods for displaying the societal implications of alternative policy responses to an aging population. The key data inputs for such models are age-specific per capita or per household measures of aggregate consumption, earnings, transfers between and within families, tax payments, and public transfer receipts. These age-specific measures, summed across individuals of each age or households headed by persons of each age, yield familiar aggregate measures of consumption, labor income, and so on that appear in conventional national income accounts. The aggregate age-specific measures are derived from a variety of underlying sources, including survey data on consumer expenditures, labor earnings or intrafamily transfers, and administrative records of tax payments and beneficiary payments. (See, for example, Lee, 1994a, for a description of data sources used to construct such measures for the United States.) The main requirement is that the underlying data sources have information on age and household structure along with the relevant economic measures.

The intellectual origins of this line of research can be traced to a seminal paper by Samuelson (1958) that introduced the so-called “overlapping generations” model. This model uses a highly stylized demographic structure in which people live for two periods as “young” workers and “old” retirees. In any given period, the population is made up of the overlap of surviving members of the generation born during the last period, who are now old, and those born in the current period, who are now young. Arthur and McNicoll (1978) incorporated more realistic demography into this model by assuming that both time and age are measured as continuous variables, that the individual life span is finite and subject to age-specific mortality risks, and that new generations arrive over time as a continuous flow of births according to a given age-specific fertility schedule. In addition, they introduced savings and physical capital into the model, along with the assumption that the level of aggregate output depends on the aggregate quantity of labor and capital. More recently, Willis (1988) extended the model of Arthur and McNicoll to consider the role of intergenerational transfers through the family, state, and market in an age-structured model, and showed how various transfer policies may influence the national savings rate and the equilibrium rate of interest. In a series of papers, Lee and colleagues (Lee and Lapkoff, 1988; Lee, 1994b; National Research Council, 1997; Lee, 2000) have imple-

Page 161

mented this model empirically, and in conceptually related work, Auerbach et al. (1991) have developed a “generational accounting” model to assess public-sector intergenerational transfers.

Arthur and McNicoll (1978) address the question of whether a small increase in the rate of population growth raises or lowers per capita lifetime consumption in steady state. 2 We reverse their focus by asking about the economic effects of a decrease in the rate of population growth. This question is at the very core of the debate over the economic consequences of population aging and the efficacy of alternative policy responses. Standard neoclassical economic growth models of the type described by Solow (1956) and Diamond (1965) imply that low rates of population growth will always increase feasible consumption because of “capital deepening.” That is, as the rate of population growth decreases, smaller shares of output need to be diverted away from consumption and toward investment to maintain a fixed amount of capital per worker. This beneficial effect of lower population growth was stressed by Coale and Hoover (1958) and many others in connection with discussions of policies aimed at reducing fertility in developing countries that were experiencing rapid population growth after World War II.

In a model that ignores the effects of age structure, lower rates of population growth always tend to raise per capita consumption because of the capital-deepening effect. This conclusion may not hold in an age-structured model because of an intergenerational transfer effect. Changes in the rate of population growth will produce such an effect whenever there are net aggregate transfers taking place between members of different age groups. These transfers may be in either direction, from young to old or from old to young, and they may occur in the institutional context of the family, state, or market. For example, transfers through the family may take the form of parental expenditures on children or old-age support provided by children for their parents; transfers through the public sector may involve tax-supported public education or pay-as-you-go social security programs; and implicit intergenerational transfers may take place through credit markets if lenders, on average, are either older or younger than borrowers.

Changes in the rate of population growth produce an intergenerational transfer effect because they induce a change in the age structure and, hence, alter the relative numbers of people who give or receive trans-

2The models discussed in this section employ a “comparative steady state” approach in which the long-run demographic and economic structure of a society whose population is growing at, say, 1 percent per year is compared with that of a society whose population is decreasing at a rate of 1 percent per year. Later, we briefly discuss some important questions associated with a transition in population growth from a higher to a lower level.

Page 162

fers. On the one hand, a decrease in the rate of population growth increases the fraction of elderly in the population and therefore increases per capita lifetime consumption opportunities for members of each generation if the old tend to make net transfers to the young. For example, if parents transfer a given amount of resources to each child and there are fewer children because of a reduction in fertility, the resources available for consumption by adults will increase without reducing the amount consumed by each child. On the other hand, a decrease in population growth will reduce per capita lifetime consumption if net transfers are from the younger to the older generation.

It is important to distinguish between the effects of population aging on the potential economic welfare of the society as a whole and on particular programs within the public sector. For example, the fertility decline that is leading to population aging in the United States and other Western countries may have the long-run effect of increasing potential per capita lifetime consumption if the direction of net intergenerational transfers is from the older to the younger generation. In this case, the intergenerational transfer effect reinforces the capital-deepening effect. However, the effect of population aging is likely to cause increasing problems for public-sector transfer systems. In countries that finance old-age security through pay-as-you-go public pension schemes in which the direction of intergenerational transfers is from the younger to the older generation, it has become acutely obvious to policy makers that population aging may make it impossible to maintain such programs without increasing payroll taxes or reducing retirement benefits.

In the next section, we present some empirical findings to illustrate the direction and magnitude of transfer systems in countries at different levels of economic development and in various subsystems of transfers that operate through the family and the public sector.

The Direction of Intergenerational Transfers and Economic Development

Much of the demographic literature would lead policy makers to expect major shifts in the patterns of assistance among generations of kin as economic development progresses. Of particular note is Caldwell's (1976) theory that the direction of wealth flows reverses in the course of economic development. He argues that there are two types of societies: pre-transitional societies in which transfers from young to old are motivated by high fertility, and post-transitional societies characterized by levels of low fertility and net transfers from parents to children. This theory has been called into question on both theoretical and empirical grounds, most explicitly by Kaplan (1994:755) who argues:

Page 163

In contrast to wealth-flows theory, models of fertility and parental investment derived from evolutionary biology expect that the net flow of resources will always be from parents to offspring, even when fertility is high. The logic underlying this expectation is that natural selection will have produced a preponderance of organisms that are designed to extract resources from the environment and convert those resources into descendants carrying replicas of their genetic material.

Careful empirical measures of age-specific consumption and production among primitive hunter-gatherers produced by Kaplan and other anthropologists indicate that individuals tend to produce more than they consume at every age. The implication is that net transfers are downward, from older to younger generations.

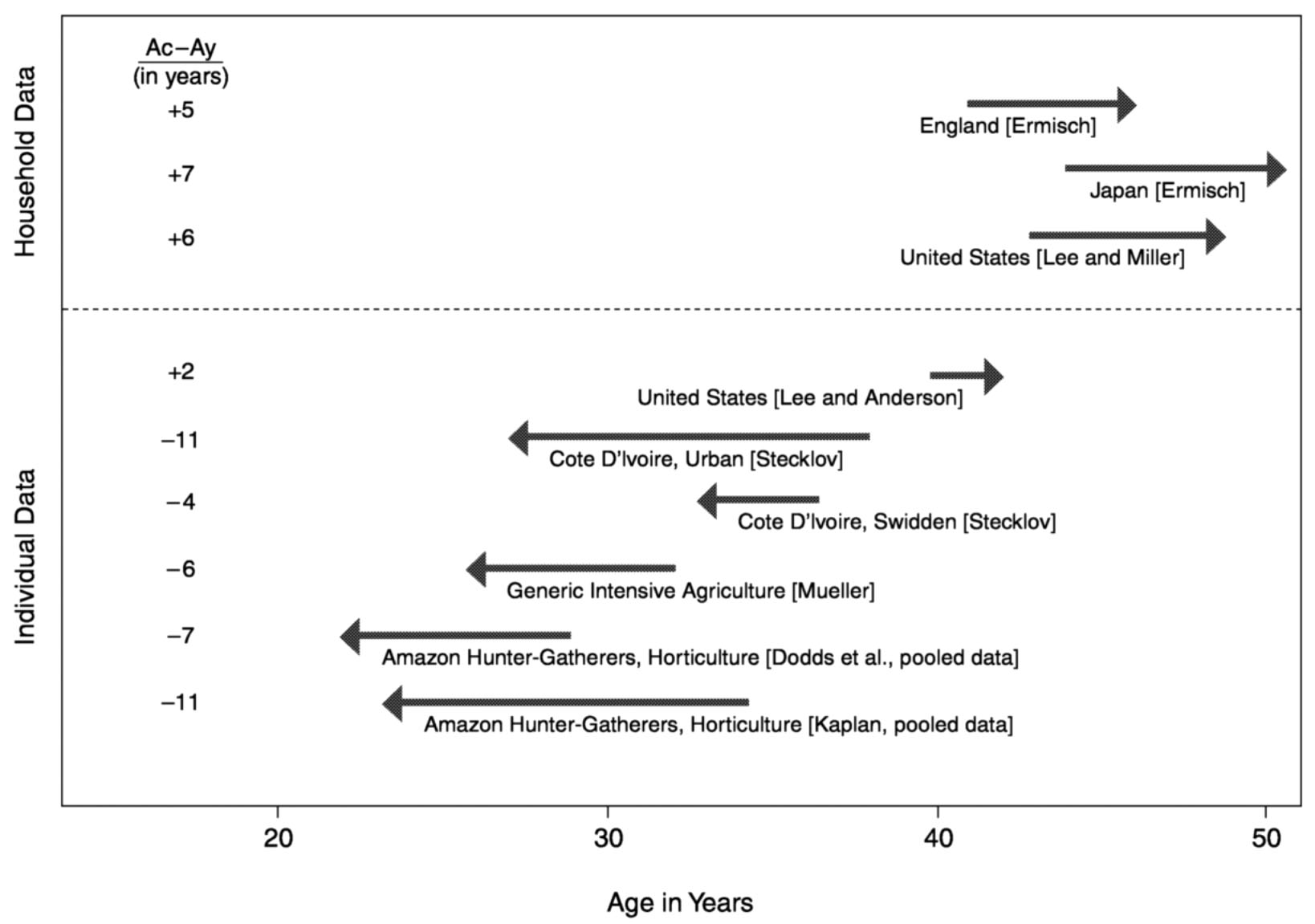

Empirical measures of net transfers in peasant societies are summarized in Figure 5-1 for several different societies, ranging from the hunter-gatherer tribes studied by Kaplan, to urban and rural areas of Cote d'Ivoire studied by Stecklov (1997), to measures for the United States calculated by Lee (1994a). The lower panel of the figure measures Ac − Ay, the difference between the mean age of consuming and the mean age of producing over the individual life cycle, using a clever geometric device of Lee's (1994a) invention. The tail of each arrow is located at the average age of production (Ay), and the head is located at the average age of consumption in the population (Ac). The length of the arrow is the number of years traversed by the average transfer. This distance measures the magnitude of the intergenerational transfer received or given as a proportion of the present value of lifetime income for a representative person in the society. 3 An arrow that points to the left indicates that the direction of net transfers is downward, from the older to the younger generation; an arrow that points to the right indicates an upward net transfer from the younger to the older generation. The vertical position of the arrows orders the society by the magnitude of the downward transfer.

The arrows in the lower panel of Figure 5-1 tell a clear and remarkable story. In all of the societies depicted except for the United States, net transfers are downward, as predicted by evolutionary theory, rather than upward, as predicted by Caldwell's wealth flows theory. Moreover, the magnitude of the transfers, as measured by the length of the arrows, is largest for the most primitive group, of intermediate length for the developing country, and small and of opposite sign for the most advanced country. Recall that the sign of (Ac − Ay) indicates the effect of higher population growth on the feasible level of per capita lifetime consumption, ignoring capital-dilution effects. The left-pointing arrows indicate

3This model assumes that the society is in a steady-state golden rule equilibrium with a constant rate of population growth equal to the rate of interest.

Page 164

FIGURE 5-1 Direction and magnitude of intergenerational transfers: A cross-society comparison. SOURCE: Lee (2000). Reprinted with permission.

~ enlarge ~

Page 165

that a reduction in the rate of population growth would have a quite beneficial effect on per capita lifetime consumption for the hunter-gatherers and a smaller but distinctly beneficial effect in Cote d'Ivoire. The reason for this is that individuals within these two societies consume more than they produce at the beginning of life, but once they reach adulthood, they produce more than they consume until they die. Thus adults in these societies make investments in the next generation that are never repaid. In contrast, (Ac − Ay) in the United States is positive, indicating that an increase in fertility would generate a positive intergenerational transfer effect that would be partially offset by a negative capital-dilution effect associated with the additional investment needed to equip more workers with a given amount of capital.

The direction of intergenerational transfers in the United States and other advanced countries differs from that in less developed countries and primitive societies for two main reasons. First, in the advanced countries, the elderly as well as children consume more than they produce, and they do so primarily as a consequence of reduced labor income. In short, unlike low-income societies, high-income societies provide for retirement transfers to fill the significant income gap that exists between the end of working life and death. Second, high-income societies are all experiencing very low rates of population growth and low mortality, so that the proportion of dependent young in these societies is far smaller than in high-fertility societies, while the proportion of dependent aged is much higher. These two factors tend to offset the fact that high levels of human capital investment in education and on-the-job training in the advanced countries result in a shift of individual productivity to later ages. 4

Intergenerational Transfers in Developed Countries

The mechanisms by which intergenerational transfers take place through social, political, or economic institutions may be examined using modifications of the basic Arthur and McNicoll (1978) model as implemented empirically by Lee (1994a). By shifting the unit of analysis from the individual to the household, Lee explicitly introduces the family into the model. The arrows in the top panel of Figure 5-1 are based on household rather than individual measures of age-specific consumption and production for three advanced countries—England, Japan, and the United

4It should be noted, however, that Kaplan (1994) finds that male age-productivity profiles are positively sloped for a considerable period of time, reflecting, he argues, a considerable amount of learning required to become an efficient hunter. Thus, investment in human capital may be important even in very primitive societies.

Page 166

States. In this panel, age refers to the age of the household head, and consumption and earnings are measured at the household level. Conceptually, the change in the unit of analysis from the individual to the household means that the measure of intergenerational transfers given by (Ac − Ay) accounts for only those transfers that take place between households. Age-differentiated transfers that take place within households in the advanced countries reflect primarily parents' private expenditures on their children, a downward transfer. 5 Within-household transfers also include the financial and time costs of assisting coresidential parents. These costs, which are upward transfers, are not included in the estimates shown in Figure 5-1, but are assumed to be relatively small when averaged over the entire population. Consequently, the magnitude of the between-family measure of (Ac − Ay) for the United States in the top panel of Figure 5-1 is even more positive than the corresponding measure of (Ac − Ay), at the individual level in the lower panel.

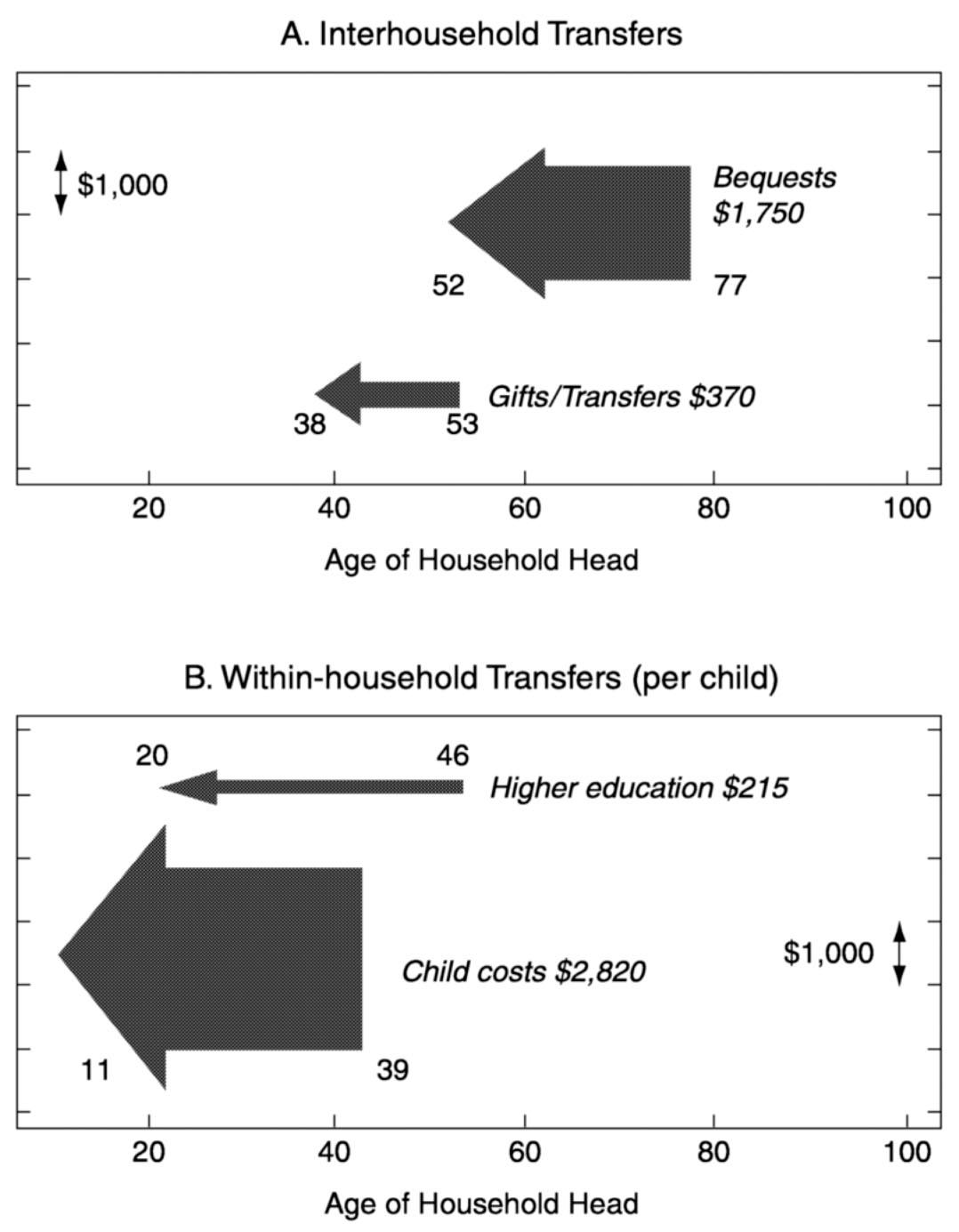

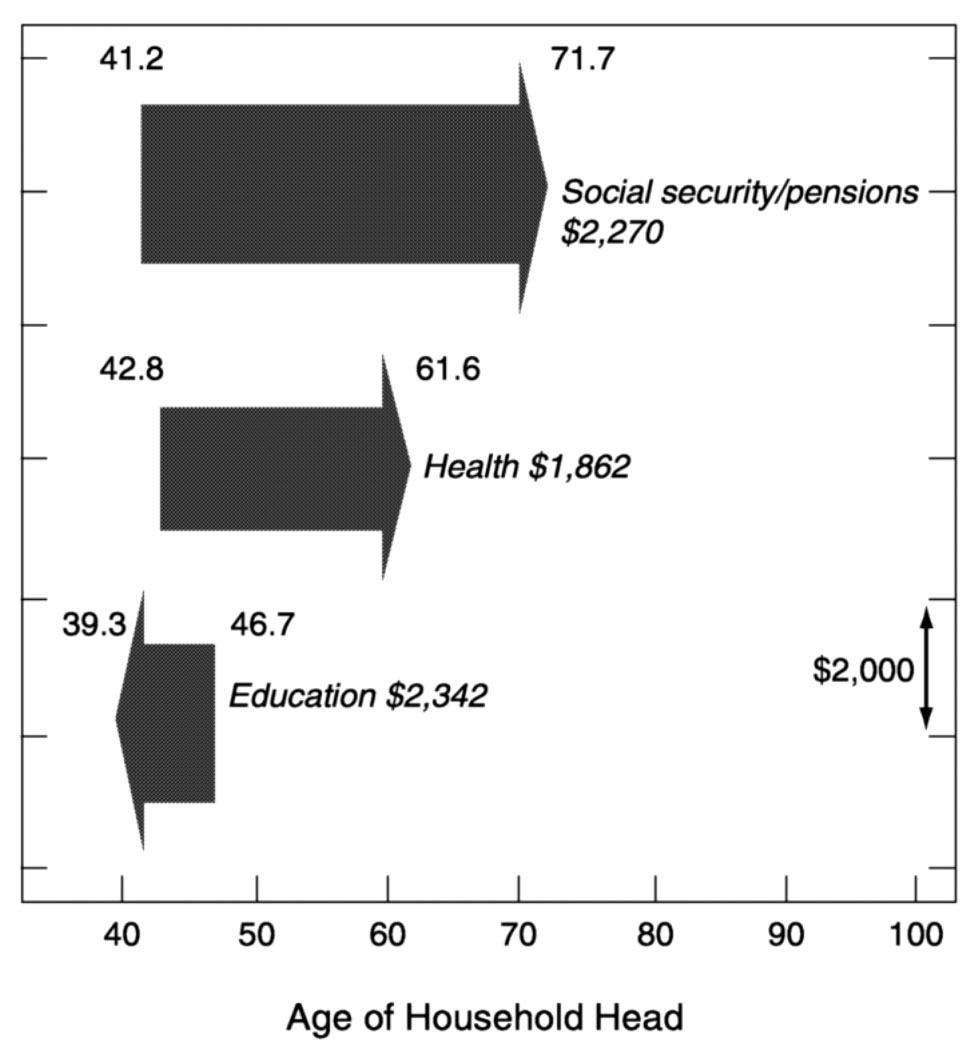

The difference in the direction of familial and public transfers for the United States in the 1980s is illustrated vividly in Figure 5-2 and Figure 5-3, respectively. In addition to length and direction as in Figure 5-1, the arrows in these two figures vary in width, indicating the annual flow of resources associated with a given transfer, while the area of the arrow (length times width) indicates the total intergenerational transfer per household.

All components of familial transfers shown in Figure 5-2 are downward. Panel A measures interhousehold transfers due to bequests and inter vivos gifts. Bequests are given by household heads who average age 77 at death and are received by households headed by persons 52 years of age, a difference of 25 years. These transfers amount to a flow of $1,750 per year, and the total bequest transfer per household is $43,750 = (77 − 52)1750. Inter vivos gifts are much smaller, averaging $370 per year; are given and received at younger ages, 53 and 38, respectively; and total $5,550. Within-household transfers, measuring private childrearing and higher education costs per child, are shown in Panel B of Figure 5-2. Child costs are paid by parents who average 39 years of age to children who average 11 years of age. The flow value of child costs is $2,820 per year per child, and the total transfer is $78,960 per child. Transfers to pay the costs of higher education are from parents averaging 48 years of age to children averaging 20 years of age. They have a flow value of $215, and the total transfer is $6,020 per child.

5Within-household transfers also include the financial and time costs of assisting coresidential parents. These costs, which are upward transfers, are not included in the estimates shown in Figure 5-1, but are assumed to be relatively small when averaged over the entire population.

Page 167

FIGURE 5-2 Familial transfers in the United States (data from the 1980s). NOTE: The top panel describes flows of transfers between households; the bottom panel describes flows of transfers within households. The tail of each arrow is located at the average age of making each kind of transfer in the population, and the head of the arrow is located at the average age of receiving each kind of transfer in the population. The thickness of each arrow represent the per capita (or per household) flow of each kind of transfer, indicated by the number below each label. The area of each arrow equals the average net transfer of each kind expected to be received by the average person or household over the remaining lifetime, and is negative if the arrow points to the left. SOURCE: Lee (1994b). Reprinted with permission.

~ enlarge ~

Page 168

In contrast with private familial transfers, the public transfers shown in Figure 5-3 are predominantly upward from younger to older generations. The largest public transfers in the United States are associated with the social security system. In Figure 5-3, workers who pay the social security payroll tax are in households whose head averages 41.2 years of age, while beneficiaries are in households in which the head averages 71.7 years of age. With a flow value of $2,270 per year, the total lifetime social security transfer is $69,235 per household. Health care costs are the other major source of public-sector intergenerational transfers. These transfers are received by households whose heads average 61.6 years of age and are funded by taxes paid by households whose heads average 42.8 years of age. The flow value of health costs is $1,862, and the transfer totals

FIGURE 5-3 Public-sector transfers to and from households in the United States (data from the 1980s). NOTE: See note to

Figure 5-2. The tail of the arrow is located at the average age of paying taxes in support of each kind of transfer, and the head at the average age of receiving each kind of transfer, in each case based on the age of the household reference person. Data combine federal, state, and local transfers. SOURCE: Lee (1994b). Reprinted with permission.

~ enlarge ~

Page 169

$35,005, about half the size of the social security transfer. Education is the only major public-sector transfer in a downward direction. While the flow value of $2,342 per year is comparable to the flow value of the social security transfer, the magnitude of the total intergenerational transfer, $17,330 per household, is much smaller because there is only a 7.4 year difference in the average age of household heads who pay education taxes (46.7 years of age) and heads whose households receive public education. On balance, net public-sector intergenerational transfers from the younger to the older generation in the United States outweigh private household transfers from the older to the younger generation, as shown by the right-pointing arrows for the United States in Figure 5-1.

Implications

The preceding discussion has several important implications for the direction and magnitude of net intergenerational transfers and the institutional mechanisms through which they flow. The net supply of saving from the household sector, measured at the point at which the rate of interest is equal to the rate of growth, is equal to the net intergenerational transfer through familial, public, and market mechanisms (Willis, 1988). Any transfer in an upward direction, such as the social security and health transfers depicted in Figure 5-3, reduces the net savings of the household sector, while any transfer in a downward direction, such as family expenditures on childrearing and higher education shown in Figure 5-2 or public expenditures on education shown in Figure 5-3, increase the supply of savings. Thus, the willingness of the older generation to finance investment in the human capital of their children, either privately as parents or publicly as taxpayers, also enhances the society's accumulation of physical capital by increasing the supply of savings and reducing the equilibrium rate of interest. On the other hand, Feldstein (1974) argues that programs such as social security and Medicare that generate upward transfers through the public sector tend to reduce the supply of savings, raise the rate of interest, and reduce the accumulation of physical capital in a society.

Interesting and important behavioral questions underlie the accounting relationships depicted in Figure 5-1, Figure 5-2 through Figure 5-3. In particular, the ultimate impact of a change in a public transfer program depends on the motivations and behavior of individuals and families. For example, Feldstein's argument that pay-as-you-go social security programs reduce savings assumes that households follow a model in which savings serve to smooth consumption over the life cycle. A tax during working years followed by a benefit during retirement years reduces the variability of life-cycle income, thereby decreasing the need for savings. In the life

Page 170

cycle model employed by Feldstein, individuals care only for their own consumption. Barro (1974) shows that Feldstein's conclusions may be reversed if parents are altruistic toward their children. To maintain a balance between their own utility and that of their children, altruistic parents offset public social security transfers from the younger generation by equal and opposite private transfers to their children, thus neutralizing the effect of social security on saving. 6 It has been difficult to determine the empirical effect of public transfers on national savings and the aggregate capital stock, largely because of a lack of comparable international data on savings behavior that could exploit cross-national variations in public policy to identify these effects.

Public transfers also create a potential divergence between the private and social costs of childbearing. As noted earlier, the sign of Ac − Ay, measured at the individual level, indicates whether higher population growth will raise or lower potential lifetime consumption. In the case of the United States, as discussed above, the arrow based on individual data in the bottom panel of Figure 5-1 indicates that a small increase in the birth rate would have a slightly positive effect on permanent per capita lifetime consumption. Under the usual assumptions of economic models of fertility, households have children up to the point at which the marginal cost of children of given quality is equal to the monetary value of the utility gain from an additional child.

The arrows in Figure 5-2 depicting familial transfers in a downward direction indicate the net private cost of children to parents, which, according to the theory, are balanced against the utility gains from children. While a reduction in fertility would increase the consumption of the adult household members, the loss of utility would be at least as great as the gain in utility from increased consumption. The arrows in Figure 5-3 show that public transfers are largely upward, from the younger to the older generation. This implies that an increase in the birth rate would allow workers to pay lower taxes per capita, holding per capita public transfers to the older generation constant. This social benefit, however, creates no private incentive to increase fertility. Thus, an extra birth by a given household will benefit others because of the social security taxes the child will pay as an adult. An insignificant fraction of this benefit, however, accrues to the biological parents, who make fertility decisions and bear the private costs of children. The estimated size of this external

6Kohli (1999), studying the redistribution of aggregate income in the former East Germany after reunification, argues that a portion of public transfers to the elderly is “channeled back” to younger kin. While potentially inefficient, Kohli argues that rerouted transfers have a greater welfare effect than that produced by direct public transfers to younger persons.

Page 171

benefit to childbearing in the United States is about $200,000 per birth (National Research Council, 1997). This analysis suggests that many of the public policy issues associated with population aging are a consequence of providing goods, services, and income for the aged through unfunded public transfer mechanisms. These mechanisms may distort savings, but such distortions could be eliminated by shifting to funded pension and health insurance programs requiring increased real saving.

COLLECTION OF DATA ON INTERGENERATIONAL TRANSFERS

The preceding discussion underscores the fact that the nature and direction of intergenerational transfers may differ greatly from one social context to another. Each society develops a set of mechanisms, including formal and informal elements, that define the timing and content of support, the appropriate participants, and their mutual obligations. The depth and complexity of these systems allow for wide variation in the facets that are measured and in the research methods employed. For example, in economic terms alone, an older person no longer in the labor force may have income because of accumulated wealth and savings, income from a government or private pension, and/or income or material support from one or more children or other relatives. To capture these flows requires attention to several dimensions, among them the source of the income, the amount, and the nature of the provider (amount of assets, type of pension or social security arrangement, characteristics of the children). To complicate matters, it is also possible that the older person in question will be extending material support to others (e.g., to a parent or child), necessitating similar detail on the economic supports provided.

When this potentially complex matrix of exchanges and their characteristics is multiplied by other important types of support—the provision of physical assistance or assistance with household duties, emotional support and companionship—the limits of subtlety of survey questionnaires and reasonable interview length are quickly approached. It is probably not too much of an exaggeration to say that there are as many approaches to appraising intergenerational transfers as there are questionnaires, as each research team achieves a unique compromise among the constraints and challenges inherent in the situation.

The goal of this section is to enumerate the main dimensions of intergenerational transfers and to suggest several reasonable strategies for obtaining the salient information on each. We follow Soldo and Hill (1993) by defining intergenerational transfers as a generic term used to describe the redistribution of resources within an extended family structure, incorporating both inter- and intrahousehold exchanges. This focus on the family does not diminish, of course, the need to collect detailed

Page 172

information on the supports received from the community, the state, and friends and neighbors. Not only are these sources major providers of certain types of support in some countries (such as pension and social security income in industrialized nations), but the existence of these sources can also have an effect on the likelihood and amount of support forthcoming from family members (Schoeni, 1992).

Outlining an Intergenerational Support System

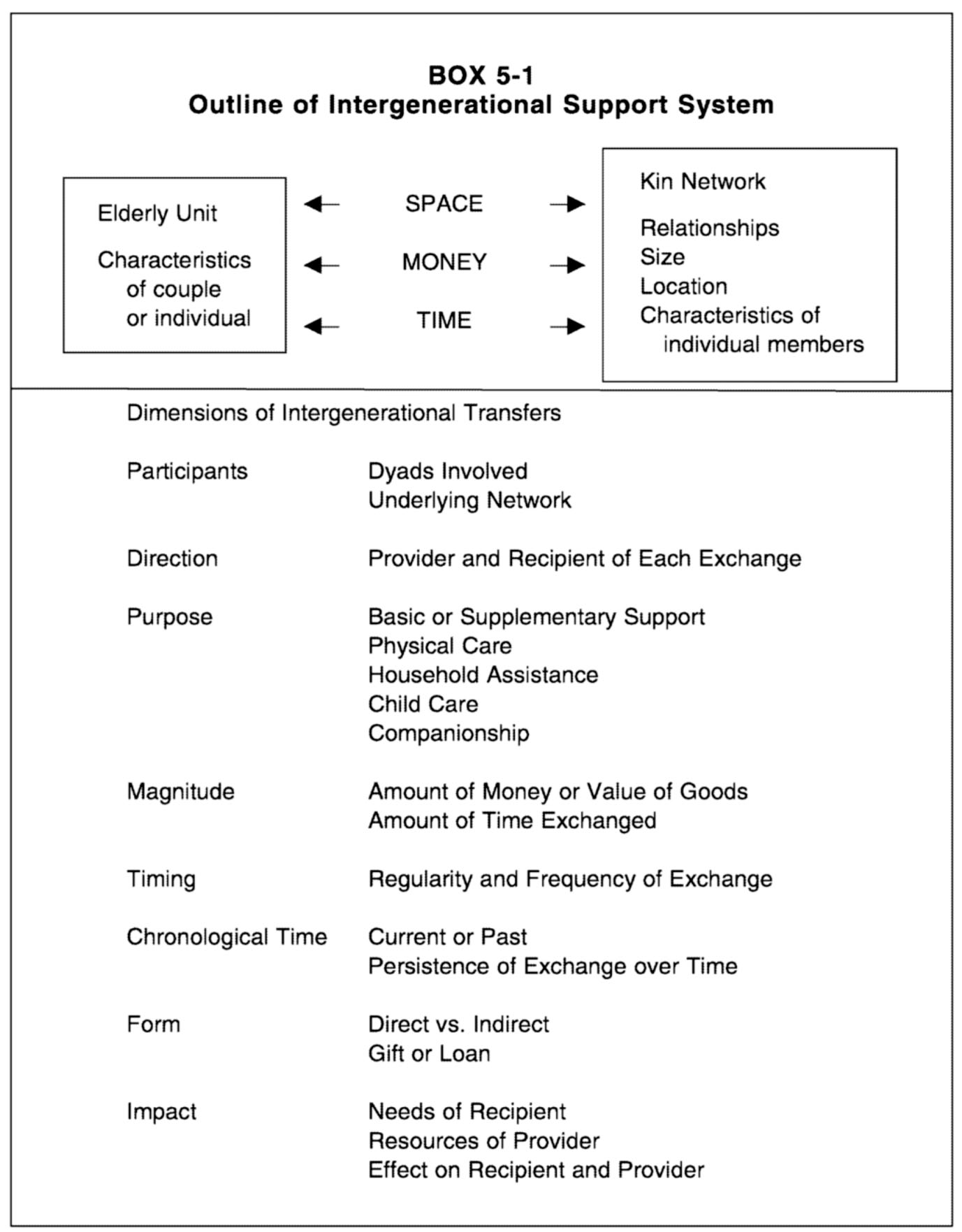

If we conceive of inter generational transfers as a series of exchanges between an indexed elderly person or couple (i.e., the focal point of the investigation) and his and/or her family network, the major components of this exchange system include who is involved, what is exchanged (and sometimes where), the quantity of the items exchanged, and when the exchange takes place. In addition, one often wishes to know how important the exchange is to the recipient and how much of a burden it represents to the provider, as well as the motivations behind it. Though this listing is straightforward, operationalizing these dimensions can be complex and presents the analyst with a number of difficult options. The scheme shown in Box 5-1 portrays the components of a support system in more detail as a starting point for identifying their implications for survey questionnaires.

The top panel in Box 5-1 highlights the need to properly identify the focal elderly unit and the kin network with which exchanges are carried out, and shows the three major “currencies” of transfer—space, money, and time. The second panel lists the salient dimensions of each exchange, providing a partial checklist of attributes that might be measured for either individual transfers or classes of transfer. These include such basic characteristics as the parties to the exchange, the purpose of the transfer, and the magnitudes involved, as well as less obvious aspects, such as the form, timing, and impact of the transfer.

Mapping the Kin Network

The starting point in describing an intergenerational support system is defining the kin network of reference and measuring its characteristics. Though technically this stage may not involve actual exchanges, it is vital in several respects. Mapping the number, location, and characteristics of kin serves as the denominator against which the frequency and nature of exchanges can be gauged. Certain types of assistance (e.g., physical assistance) are difficult to provide at a distance, and it is important to distinguish those elderly who do not receive such types of assistance because of the lack of potential caregivers from those who do not receive that assis-

Page 173

BOX 5-1Outline of IntergenerationalSupport System |

tance for other reasons. In addition, knowledge of the kin network is essential for testing competing hypotheses about the motivations and social dynamics of exchanges, such as the differences in assistance provided by or received from sons and daughters (Lee et al., 1994). From a practical standpoint, identifying the kin network in detail often makes it easier to record the exchanges that take place with specific members and

Page 174

serves to remind the respondent of the relevant set of possible providers and beneficiaries.

Defining the kin network is not straightforward, as the salient relationships may vary across societies and over time within societies. It has been noted that data on kin structures tend to be anchored in samples of older persons rather than younger individuals. That is, we often obtain “top-down” instead of “bottom-up” views of family structure, although the latter may be equally useful (Hagestad, 2000). Another key decision is the amount of detail to collect about each member and whether this should vary with the nature of the relationship. Current practice ranges from recording summary numbers, perhaps by broad geographic location, to establishing a detailed matrix that enumerates each member and his or her characteristics separately. 7 We argue below that reasonably detailed information should be collected about parents and children of the respondent. Whether siblings and other kin should be treated in the same fashion will depend on the culture and on the degree to which contact and exchanges with these kin are customary. It should be noted that for elderly respondents who are currently married and coresiding with their spouse, information will often be needed about key relatives of each, as well as about children that may not be jointly theirs.

A major decision is how to treat members within the household versus those residing outside. We recommend that detailed information be collected about each household member, regardless of his or her relation to the elderly respondent. Since there can be more than one married child and set of grandchildren coresiding, as is often the case in some developing countries, it is useful to distinguish the parent of each grandchild in the household. And since elderly parents may be coresiding with the indexed respondent, one will usually wish to ascertain the state of their health, as well as other characteristics common to all household members—information that is particularly useful in assessing ongoing or potential caregiving burdens. Another important concern is how long each member has lived in the current household, which together with information about the elderly respondent's own moves, can reveal whether the

7A variety of grid-like survey instruments have proven useful in recording the multiplicity of potential exchanges (see, e.g., Hermalin, 2000). Where feasible, computer-assisted interviewing, either in person or by telephone, opens up many possibilities for keeping track of various classes of individuals. For example, a grid of coresident and noncoresident family members can be called up whenever questions on exchanges arise, and the pertinent information recorded. With paper questionnaires, considerable ingenuity must be employed to ensure that the interviewer has all of the relevant information on hand at each stage.

Page 175

respondent joined an existing household or when others joined a household established by the respondent. Similarly, discussion of household dynamics can lead to questions about who is the head of the household (in economic as well as nominal terms) and about ownership of the home and land, all central to an understanding of the nature of transfers involving space.

Moving beyond the household multiplies the number of decisions concerning the kin to include and the information to collect. Experience from Asian surveys (see Ofstedal et al., 1999) suggests a detailed strategy for the closest kin, with more summary measures reserved for distant relations. Two data considerations are particularly critical: the geographical location of each of the children and any surviving parents, and the relevant characteristics of these network members. For children, one wishes to know not only their basic sociodemographic characteristics, but also information about the stage of family building (e.g., number of children and age of oldest child) and occupation of the spouse. In terms of geography, it may be desirable to obtain even more detail, such as the distance or time to reach each child (or vice versa) and the usual means of transportation. And in some countries, information on family members living outside the country can be valuable in light of important remittances often made by overseas contract workers to family households.

Information on the spatial network of children forms the backdrop for understanding the frequency of contact between the elderly respondent and his or her noncoresident children. The frequency and nature of contacts reflect in part the intergenerational exchange of time, another important currency in measuring transfers. As before, the amount of detail will vary with the particular situation. It may be most useful to measure the frequency of personal visits (ranging from “every day” to “have not seen for a long time”) and the frequency of contacts by phone and letter. In other instances, one may also want to distinguish whether the visit takes place in the home of the elderly person(s) or that of the child (i.e., who visits whom).

In addition to this range of information about noncoresident children, the health, location, and frequency of contact should be obtained for noncoresident parents of the indexed respondent (and spouse). This information can be collected as a subset of the questions asked of noncoresident children or as part of a separate inquiry about parents, including important information about deceased parents (such as age at death, cause of death, and where living when died).

For other relatives beyond children and parents, it is often necessary in the interest of time to obtain summary information, which can still provide insights into the size and strength of the kin network. During development of the 1989 Taiwan Survey of Health and Living Status of

Page 176

the Elderly, for example, it was expected that siblings might be a strong source of support (Hermalin et al., 1996). Consequently, the location of and contact with siblings were mapped in some detail but still in a summary fashion, while information about other relations was curtailed even further. In the U.S. Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), by contrast, detailed information was obtained about four siblings of the respondents with at least one living biological parent, a sample selection table being employed when there were five or more siblings (Soldo and Hill, 1995).

In addition to mapping the kin network, attention should be given to carefully defining the elderly unit in question. If the elderly respondent is single, widowed, or divorced, little confusion is likely to arise in tracing the exchanges between the respondent and his or her network. When the respondent is currently married, however, care must be exercised as to whether the questions are intended to cover the couple or the particular respondent. Although visits and transfers of money or goods are likely to be for the benefit of the couple, this will not always be the case. If the intent is to measure exchanges in which the couple is involved, this should be made clear from the structure of the questionnaire. In practice, one will usually seek a mix of respondent and couple responses. In asking about the receipt of physical assistance or assistance with household duties or about specific forms of companionship or emotional support, the focus is almost always on the respondent. But questions about financial support or more general patterns of visiting are often formulated with the couple in mind. Similar caution is needed in tracing what the elderly unit does for others. Should the focus be on what the couple does or what the particular respondent does in terms of financial assistance, taking care of grandchildren, assisting children, and so on?

Measuring and Recording Exchanges

In the previous section we indicated how information on the transfer of space through living arrangements can be gathered in the course of obtaining details about household structure. Here the emphasis is on exchanges of money (or its equivalent) and time. Broadly speaking, there are two strategies for obtaining this information: one is person-centered and involves asking whether exchanges of certain types have occurred with named individuals or classes of individuals; the other is exchangecentered and involves asking whether exchanges of specific types occurred, and if so, obtaining the names or classes of the individuals involved (assistance from governmental and nongovernmental organizations can be ascertained separately). Few survey instruments are entirely of one type or another, so both strategies are likely to be found in the same

Page 177

protocol. Another decision in survey design is whether to concentrate the exchange questions in one section or to decentralize them by topic—pursuing, for example, questions on physical assistance in a section on health and questions on financial assistance in a section on income. Again, these strategies are often mixed, with some exchanges being grouped and others dispersed.

A person-centered structure in a survey of elderly individuals requires inquiry about exchanges with each coresident and noncoresident child, even if no such exchanges have taken place. This approach therefore reduces the chance that a given exchange will be overlooked and provides a convenient way of recording the information and connecting it to the characteristics of the children. On the negative side, insofar as there are relatively few exchanges of a given type, it can be time-consuming and tedious to go through a long list of possible participants (e.g., parents, parents-in-law, grandchildren as a class, siblings as a class, and all other relations).

With the exchange-centered approach, the respondent is not probed about each possible provider, but since these questions come after the kin network details, the range of potential providers should be well in mind. Focusing on the exchange puts more pressure on ensuring that the persons named as giving and receiving assistance are recorded properly, so that the nature of the transfer can be aligned with their personal characteristics.

Any survey instrument that seeks to quantify transfers needs to establish a respondent's need for different types of assistance and the sufficiency of the assistance received. Measuring need is a critical aspect of understanding intergenerational transfers since we expect the existence of need and its extent to be a prime determinant of the provision of support. There are different strategies for establishing need, and the approach used can vary with the type of support involved. One tactic is to assume that those receiving assistance have a need, and hence to focus on identifying the suppliers and the sufficiency of the assistance received. This is not necessarily the best strategy, but its use is prompted by concern that a direct question on whether a respondent has certain needs could be met with denial, foreclosing the possibility of obtaining information about associated transfers.

Understanding the transfer of money or its equivalent has a number of dimensions in addition to ascertaining recent exchanges. Special gifts or loans that occurred in the past to help a child or other relative pay educational expenses, open a business, travel, or meet special needs (such as medical expenses) can be important for understanding current patterns of exchange. They enter into the testing of various hypotheses about

Page 178

motivations for transfer, including reciprocity vs. altruism and investment in human capital for old-age support, that are associated with several economic theories (Lillard and Willis, 1997).

Exchanges of money or time within the household often pose more measurement challenges than interhousehold exchanges because the former exchanges can occur in a number of ways. For example, rather than providing money, those living with the elderly respondent may pay the major expenses of the household (also possible, of course, to some degree for those living at a distance). To capture these variations, it is desirable to direct some questions to household financial arrangements. This involves, for example, identifying each household member with income, measuring total household income, determining how household expenses are met (e.g., through pooling of income versus specific member contributions), identifying non-household members who cover expenses, and assessing the adequacy of income for respondent and spouse in relation to household expenses. Such questions complement the more standard ones on sources of income for respondent and spouse and the importance of each source. And, as highlighted in Chapter 4, attention should also be paid to joint ownership of assets and transfers of assets to children and others, particularly in cultures where some division of property often takes place upon retirement or well in advance of death.

Transfers of time often are considered from the perspective of the elderly as recipient, for example, assistance that the respondent might receive with various activities of daily living. Yet it is also important to account for time an elderly respondent gives to others for a wide variety of purposes. Increasingly, older parents provide child care for their grandchildren to assist working couples, and they often provide companionship as well as care to their own elderly parents. Understanding still another aspect of time transfers involves identifying the nature of emotional support and companionship received by the respondent (such as satisfaction with the willingness of family members to listen to worries and problems, accompaniment in outside-the-home activities, the degree to which respondents feel loved and cared for, and the degree to which family members can be counted on for care during illness) and identifying the specific persons most likely to provide each type of support.

As with money, transfers of time for household-related activities sometimes require special attention. For example, it is not always easy to distinguish assistance an older person receives with household chores because of a physical or cognitive limitation from assistance provided as a result of customary divisions of labor. Likewise, to get a sense of the assistance an elderly respondent provides to others through household activities versus assistance received, it is useful to obtain a picture of the division of labor for major household tasks. A further consideration is

Page 179

assessment of the caregiver burden, in terms of time and resources expended, on those providing assistance for others. This information is difficult to capture unless the caregivers are interviewed as well.

Summary of Key Measurement Issues

The intent of the above discussion is not to propose a model questionnaire, but to suggest reasonable strategies for obtaining the salient information about intergenerational transfers within the confines of a survey. As more attention is focused in this area, it is likely that consensus will emerge as to the most efficient means of pursuing the critical variables. A summary of the key strategies is as follows:

-

Map the relevant kin network both spatially and in terms of sufficient characteristics of each member.

-

Identify the specific individuals within the kin network who are providing each type of support (including elderly providers), and record the information so that these individuals can be linked with their characteristics.

-

If an elderly respondent is currently married, make clear whether the supports received or provided apply to the individual or to the couple.

-

For supports that are likely to involve a number of network members, identify the main provider by measuring the quantity of support from each or having the elderly recipient identify the key provider.

-

For transfers of money, identify large transfers over the lifetime in addition to current exchanges.

-

Pay special attention to intrahousehold transfers of money and time (in terms of household duties) since these exchanges can take a number of forms.

-

Do not overlook the assistance received and provided in the form of emotional support and companionship.

-

For the major dimensions of support an elderly respondent may receive, try to ascertain the need for and sufficiency of that support.

Having touched on the topics in Box 5-1 in the context of a household survey, we should stress that several important dimensions of intergenerational relations go beyond the confines of single cross-sectional surveys. One of these, the persistence of transfers and patterns of exchange, requires panel designs to trace whether given forms of assistance continue over time and, in particular, whether the specific exchange partners remain the same or vary as an older person ages. With life expectancy increasing throughout the world, there will likely be a series of transitions in the level and manner of the support provided, most

Page 180

obvious perhaps in terms of living arrangements. Hence, methods of measuring these transitions and the duration of various types of exchanges will become of increasing importance. Another dimension that requires alternative data collection strategies is that of understanding the direct and indirect trade-offs that occur among those providing support. If one child supports a parent with activities of daily living, for example, is that child in turn receiving any financial or other form of assistance from his or her siblings? Understanding such trade-offs and how these decisions evolve requires going beyond interviews with elderly recipients by fully involving members of the network in appropriate data collection efforts.

Although it would be desirable to develop and use comparable survey instruments in many countries, national needs and differing study goals will likely contribute to variation in the near future. At this point it may be more important for analysts to reach agreement on topics and goals and allow some variation in methods. Surveys that capture a reasonable proportion of the complexities inherent in intergenerational transfers should greatly increase the value of the analysis within each country, and soon enhance the potential of comparative research across countries and cultures.

ASSESSING FAMILY DYNAMICS AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE TRANSFER PATTERNS

Understanding and mapping the complexities of kin networks and transfer patterns is an important step in policy development. Determining how best to use such information to project future trends is the new policy frontier in many countries. The aging of populations worldwide goes hand in hand with changes in family household structure (see Wolf, 1994b, for a review). A fairly substantial (though by no means complete) literature exists with regard to the living arrangements of older persons and will not be reviewed here. (See, for example, Kendig et al., 1992; Blieszner and Bedford, 1996; Palloni, 2000; and the bibliographies therein.) Suffice it to say that living arrangements tell only part of the story of elderly well-being. Indeed, much past work has focused on the form of living arrangements while ignoring the function (Hermalin, 1997). That is, coresidence of an elderly individual with a child and/or grandchildren may or may not be a positive experience for any of the parties involved. Objective measures of living arrangements should not be used to hypothesize about subjective measures of well-being or the quality of relationships among coresident family members. This is why it is crucial to understand the nature of transfer mechanisms that operate within households, among families, and in broader community and social contexts.

Page 181

In industrialized countries with well-developed state support mechanisms, elderly persons depend upon spouses and children for emotional and psychological support and occasionally for financial aid as well. In the developing world, where pension and formal social security systems are not widely available, the elderly depend almost exclusively on family support. Past research has established that family care is an integral part of long-term care throughout the world and has a substantial impact on caregiving arrangements for the elderly (Angel et al., 1992; Kendig et al., 1992; Wiener and Hanley, 1992; Soldo and Freedman, 1994). While these basic patterns are unlikely to disappear, they will be altered by a host of factors ranging from secular trends in fertility and marital status, to changing economic and health status, to strong normative shifts relative to traditional familial obligations and the value of independent living.

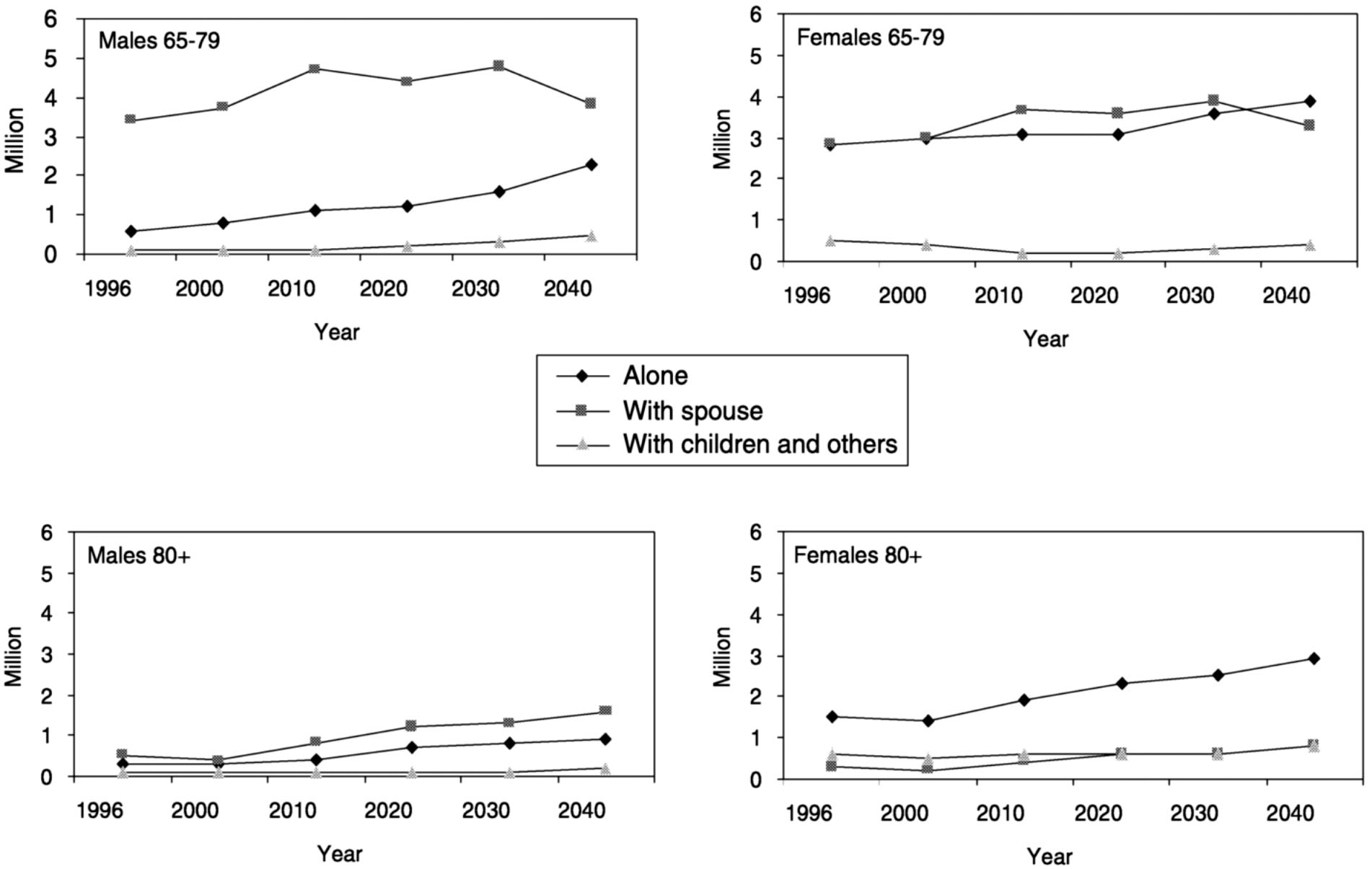

In the United States and many other developed nations, cohorts who will become the elderly of the 21st century were on the leading edge of the “family revolution,” characterized by large increases in the prevalence of divorce and out-of-wedlock childbearing and an overall decline in marriage and remarriage. The future elderly are less likely than their current counterparts to be married (Goldscheider, 1990). Clearly, planning for aging societies needs to take into account how ongoing demographic changes will alter the nature of families and households and affect intergenerational transfers (Zeng, 1988). How many elderly persons likely will live alone, with a spouse only, or with children or other relatives or be institutionalized in the future (Grundy, in press)? To what extent will people have to care for both parents and young children? What are the implications of these changes for caregiving needs and the health service system (Freedman, 1996)? Long-term care costs in the United States, for example, have doubled during each decade since 1970, reaching an annual level of $106.5 billion in 1995. Home health care costs grew 91 percent from 1990 to 1995, in contrast with 33 percent for institutional care costs (Stallard, 1998). Thus the mix of home-based and institutional care has been shifting rapidly toward home health care, especially for the oldest old (Cutler and Meara, 1999). Changes in family structure strongly affect caregiving needs, the long-term care service system, and healthrelated policy making (Himes, 1992).

Research on methodology for household and family projection addresses such questions as the above. Projection models may be grouped into three categories: those based on characteristics of household heads (headship rates); those based on household structure and living arrangements as gleaned from census or large-scale survey data (macrosimulation); and those based on kin networks, marital status transitions, and other variables often derived from in-depth survey data (microsimu-

Page 182

lation). As described below, each approach has its benefits and drawbacks.

In the global context, projecting numbers of households and their family characteristics is most frequently done on the basis of information about heads of household, as these represent the most common reference points in censuses and surveys. In many if not most countries, such data are the only available information from which to proceed and are useful in formulating at least a rough forecast of future numbers of households. However, methods based on projecting households according to the characteristics of the household head have several serious shortcomings. In surveys and censuses, the household head is often an arbitrary and vague choice (the concept of household head can vary from area to area within a country, and may change over time). A second major disadvantage is the unclear (or indirect) linkage of headship rates to underlying demographic events. This poses major problems for projection models, as it becomes difficult to incorporate demographic assumptions about future changes in fertility, marriage, cohabitation, union dissolution, and mortality (Murphy, 1991; Mason and Racelis, 1992; Burch and Skaburskis, 1993). Consequently, information produced by projections using the headshiprate method (typically with little or no information on specific household types) often is inadequate for planning purposes (Bell and Cooper, 1990). However, the most problematic feature of the headship-rate method is that it lumps all household members other than heads into an extremely heterogeneous group of “nonheads.” This categorization obviates the study of family life courses and intergenerational transfers between children and other nonheads.

To address the need for more detailed and realistic information on family structure and behavioral patterns, the study of population aging is increasingly concerned with mapping and modeling kin availability. The development and refinement of microsimulation approaches to kinship modeling (e.g., the SOCSIM model [Wachter, 1987; Hammel et al., 1991]; the KINSIM model [Wolf, 1994b]; and the MOMSIM model [Ruggles, 1993]) have made important contributions to the study of kinship patterns and family support for elderly persons. Compared with the macrosimulation approach discussed below, microsimulation methodology offers three major advantages: it can consider a large set of life dimensions with many covariates simultaneously; it can easily and explicitly retain relationships among individuals; and it provides rich output, including probabilistic and stochastic outcome distributions. However, these advantages come at a cost. Three kinds of random variations in microsimulation have been discussed in detail in the literature (see, for example, Van Imhoff, 1999). One is due to the nature of Monte Carlo random experiments, wherein different runs produce different sets of outcomes.

Page 183

Second, the starting (base) population in a micromodel is a sample from the total population, and thus is subject to classic sampling errors, especially for relatively small subgroups, such as persons of very advanced age. Third, microsimulation, which includes many explanatory variables and complex relationships among individuals, increases the stochastic fluctuations and measurement errors (specification randomness) to which the model outcomes are subject.

Keilman (1988), Van Imhoff and Keilman (1992), and Ledent (1992) review dynamic household models based on the macrosimulation approach, which has been used with some success in various nations (see, e.g., Keilman and Brunborg, 1995, for an application in Norway). Macrosimulation models do not have the problems of the inherent random variation of Monte Carlo experiments and sampling errors in the starting population. The specification randomness is present in a macromodel, but it is likely to be less serious than in a microsimulation model (Van Imhoff and Post, 1998). However, most macromodels (e.g., the LIPRO model, well known in Europe) require data on transition probabilities among various household types, data that are not available from conventional sources such as vital statistics, censuses, and ordinary surveys. Such stringent data demands are an important factor in the slow development and infrequent application of these models. Therefore, it is important to develop a dynamic household simulation/projection model that requires only conventional demographic data obtainable from vital statistics, censuses, and household surveys.

We now turn to several examples of the usefulness of simulation approaches. Several microsimulation studies have explored the implications of various schedules of unchanging demographic rates for kinship distributions; these include the LeBras (1973), Smith (1987), and Wolf (1988) studies of kinship and family support in 16 developed countries. In the latter study, three simulation variants were produced. The base scenario used fertility and mortality schedules prevailing in the 1970s as constants, while the other two incorporated substantial declines in mortality and fertility, respectively. Results indicated that continued demographic changes in developed countries would increase the proportion of elderly without living offspring. Among those elderly persons with living offspring, the average age of those offspring is approaching (or in some cases has reached) the elderly age threshold. The most important change, propelled by declining mortality rates, is a rise in the proportion of the population with a living mother.

The first detailed kinship forecasts to incorporate an observed pattern of changing demographic rates in microsimulation were produced in the early 1980s (Hammel et al., 1981). Reeves (1987) introduced divorce into the model and presented forecasts of kin for the U.S. population through

Page 184

the year 2020, quantifying the relative leverage of divorce, fertility, mortality, and marriage assumptions over various estimates. Using data from the U.S. National Survey of Families and Households and other resources, Wolf (1994a) simulated the lifetime pattern of coresidence with an aged parent and its sensitivity to demographic change. He suggested that the “coresidence expectancy” of an American adult and his or her elderly parent is quite small, but is fairly sensitive to certain types of demographic change, such as declining female mortality. Recently, Tomassini and Wolf (2000) conducted a study of the effect of persistent low fertility in Italy on shrinking kin networks for the period 1994-2050. Throughout the simulation period, some 15 to 20 percent of Italian women aged 25-45 are the only living offspring of their surviving mothers and thus are potentially fully responsible for their mothers' care. The majority of women have just one sibling with whom they could share parental care.

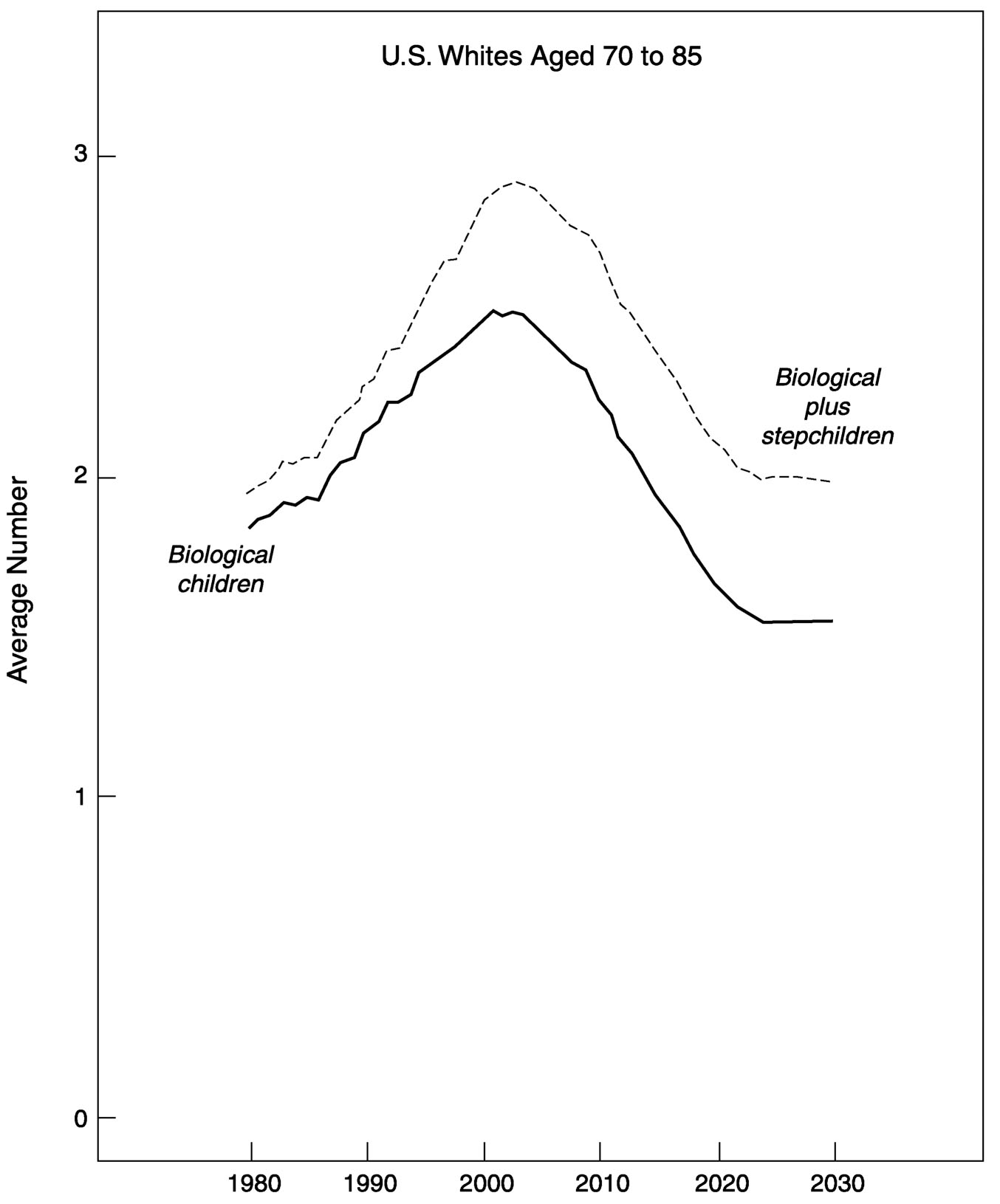

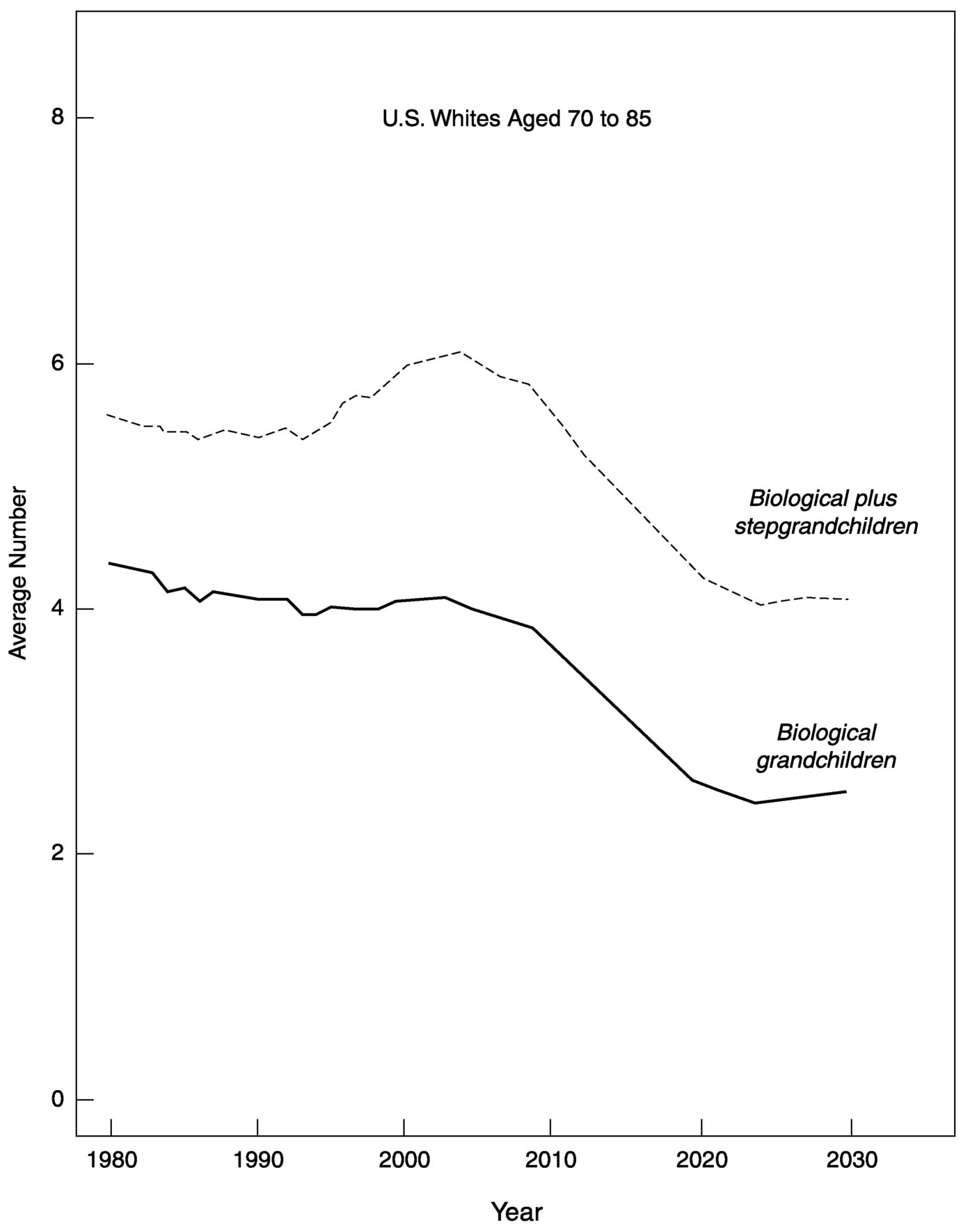

Wachter (1997,1998) took another innovative step by simulating both biological kin and stepkin. Figure 5-4 shows the sharpness of the anticipated rise and fall in average numbers of biological children and the increasing numerical prominence of stepchildren among the U.S. white population aged 70 to 85 between 1980 and 2030. By 2030, the growth in numbers of stepchildren due to divorce and remarriage wholly compensates for the net decline in average biological children after 1980. Figure 5-5 shows the predicted patterns in average numbers of biological grandchildren and biological plus stepgrandchildren for the same population and age group as in Figure 5-4. It is clear that there is a multiplier effect from the proliferation of stepchildren over two generations, and by 2030, stepgrandchildren represent more than one-third on average of all grandchildren. Stepchildren and stepgrandchildren can therefore be expected to make a large contribution to the overall pool of younger relatives for the elderly of the future.

Benefiting from methodological advances in multistate demography (Land and Rogers, 1982; Willekens et al., 1982; Schoen, 1988), Bongaarts (1987) developed a nuclear-family-status life-table model that has been applied to the United States to estimate the length of life spent in various family statuses (Watkins et al., 1987). One finding from this study is that not only have the years spent with at least one parent over age 65 risen (from fewer than 10 years under the 1900 regime to nearly 20 years under the 1980 regime), but, as a result, so has the proportion of adult lifetime spent in this status (from 15 to 29 percent). The same model applied to Korea (Lee and Palloni, 1992) suggests that declining fertility means there will be an increase in the proportion of Korean women with no surviving son. At the same time, increased male longevity means the proportion of elderly widows will also decline. Thus from the elderly woman's point of view, family status may not deteriorate significantly in the coming years.

Page 185

FIGURE 5-4 Living biological and stepchildren for whites aged 70-85 in the United States: 1980 to 2030. NOTE: Based on the output of Berkeley SOCSIM simulations, averages of 40 replications. SOURCE: Wachter (1998).

~ enlarge ~

Page 186

FIGURE 5-5 Living grandchildren for whites aged 70-85 in the United States: 1980 to 2030. NOTE: Based on the output of Berkeley SOCSIM simulations, averages of 40 replications. SOURCE: Wachter (1998).

~ enlarge ~

Page 187

From society's perspective, however, the demand for support of elderly women is likely to increase. The momentum of rapid population aging means the fraction of the overall population that is elderly women (especially sonless and childless widows) will increase among successive cohorts. Given the strong trend toward nuclearization of family structure in Korea and the traditional lack of state involvement in socioeconomic support, the future standard of living for a growing number of elderly widows in that nation is tenuous. A similar prospect looms in Taiwan and Japan (Hermalin et al., 1992; Jordan, 1995).