Appendix B

Case Studies

EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK

The Hole-in-the-Donut (HID) is a 2,509 ha (6,200-ac) mitigation bank (Florida's first) consisting of abandoned agricultural land that is surrounded by Everglades National Park land with its native vegetation (Doren 1997, ENP 1998). Recently acquired by the park, this tract is being rid of its monotypic exotic vegetation through a massive and intensive eradication program that involves removal of the exotic trees, their roots, and the soil, then allowing the native wetland vegetation to reestablish itself.

Everglades National Park was established in 1947; it is the largest national park in the United States at 0.6 million ha (1.5 million ac). Often called a “river of grass” for its shallow, slow-moving surface water, the park supports many native species and thousands of highly valued birds. Unfortunately, it also supports 217 nonindigenous plant species, which continually threaten to displace the natives (Doren 1997). The previously farmed areas of HID now support a monotypic stand of Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius) that is virtually impenetrable by humans. Found only in a small area in 1975, the pepper trees now enjoy an extensive distribution, in part due to wide dispersal of their berries by fruit-eating birds.

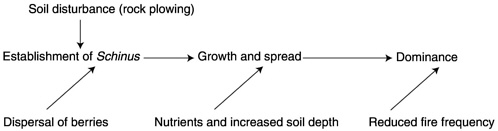

Prior to rock plowing the natural limestone rock for agriculture, the HID area was naturally dominated by a mosaic of marl prairie and related vegetation types. Two disturbances are thought to be responsible for the

ability of Schinus terebinthifolius to establish and expand following agriculture: (1) abandonment and exposure of an artificial soil and (2) reduced fire frequency (see Figure B–1). The rapid growth and high productivity of this invasive tree are likely due to changes in the soil brought about by rock plowing— namely, increased nutrient release and increased soil depth that allows seedlings to withstand 2–5 months of drought each year (Doren 1997).

Several attempts were made to remove Schinus in the 1970s and 1980s (Doren 1997). These involved herbicides, disking, bulldozing, burning, mowing, and planting and seeding of natives, hardwoods, and pines. All failed. One treatment in 1974 and another in 1983 involved the removal of rock-plowed soil down to the level of hard porous limestone substrate. The promising results led to larger soil-removal treatments 1989; soil was partially removed on 6 ha and completely removed on 18 ha. The site with partial soil removal was recolonized by Schinus, but the area without soil was not (Doren 1997).

The present effort to remove Schinus from about 2,529 ha (6,250 ac= about 10 miles2) grew out of the success of the earlier trial with total soil removal. The restoration target is a muhly grass-sawgrass prairie over 90% of the area and upland hammocks covering about 10% of the area. The hammocks, or mounds, would support pineland and hardwoods. The current plan (ENP 1998) proposes to remove about 5,000,000 yd3 of material over 20 years. Trees are first bulldozed and then shredded and composted. Sediment is trucked to fill old limestone quarries and borrow pits. Once the nearby borrow pits are filled, the spoils will be mounded in place to create upland hammocks and mowed to prevent Schinus dominance. Trees will then be planted on the mounds to restore 40 to 60 ha (100–150 ac) of pineland and hardwood forest. It is expected that one mound would be about 7 m (20 ft) high with 3:1 slopes, covering about 10 ha (25 ac). One mound could accommodate the spoils from about 7% of

FIGURE B–1 Conceptual model of factors facilitating the invasion of Schinus terebinthifolius.

the HID, drawing materials from 3 1/2 to 4 years' remediation period. Ultimately, there would be 5–12 mounds covering 60 to 80 ha (150–200 ac) or 2 to 3% of the project area. The scale of the project is also indicated by the amount of on-site trucking, which is calculated to involve 26 trucks driving over 750,000 km (458,640 miles) per year.

The current marl prairie restoration program is conducted with mitigation funds that result from a cooperative program involving Everglades National Park, Dade County, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Doren 1997). A mitigation “credit” consists of 0.4 ha (1 ac) of restoration, costing $30,000 in 1999 (M. Norland, National Park Service (NPS), personal communication). Two-thirds of the mitigation money acquired goes to restoration, and one-third goes to additional land purchase.

The scientific basis for the program is the hypothesis that soil removal will eliminate the conditions responsible for the presence of Schinus. A scientific advisory panel was established in 1996 to call for and review research proposals concerning this large-scale problem with invasive vegetation, to include studies of the current program and alternative approaches to eradication; the panel was subsequently disbanded by National Park Service administrators.

References

Doren, R.F. 1997. Restoration Research Themes and Hypotheses for Hole-in-the-Donut (HID). South Florida Natural Resources Center, Everglades National Park. [Online]. Available: http://everglades.fiu.edu/hid/ [June 28, 2001].

ENP (Everglades National Park). 1998. Environmental Assessment: Hole-in-the-Donut Soil Disposal. Everglades National Park, Florida. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Denver, CO: Denver Service Center, National Park Service. 177 pp.

COYOTE CREEK MITIGATION SITE

Synopsis

The Coyote Creek mitigation site was installed in 1993 to partially satisfy permit requirements pursuant to Section 404 of the CWA. The site was designed to provide off-site mitigation for impacts to nine creeks in Santa Clara County that were impacted by the construction of State Route 85 in San Jose, California. The mitigation goal is to develop 24.4 ac of stratified native riparian habitat adjacent to Coyote Creek, similar to riparian habitats found along other creeks (used as model sites) in Santa Clara County, California.

To achieve the mitigation goal, the ground surface elevation of an agricultural field adjacent to Coyote Creek was lowered by removing

topsoil. A levee adjacent to the field was breeched, and a diversion channel was excavated through the agricultural field to create the mitigation area. The mitigation area was then extensively planted with tree, shrub, and herbaceous riparian plant species to create four plant associations, including streamside, floodplain, valley oak forest, and slope communities.

The monitoring plan for the mitigation site called for measurement of various site parameters over a 15-year period to track the success of the site and its overall status. The two parameters used to measure success included percent survival of planted species (short-term success criteria) and establishment of a trend toward percent cover of tree and shrub species similar to that of a mature riparian community (long-term success criteria). In addition, other parameters to be monitored at the site included species composition, plant vigor and health, plant height, basal area, natural reproduction, species diversity, root development, hydrology, and photo documentation. While all parameters were to be measured, only percent survival (short-term success criteria) and a trend toward mature percent cover (long-term success criteria) were used to judge the overall success or failure of the mitigation site. The short-term success criteria called for the survival of 60 to 90% of planted riparian species measured over a 5-year period. The long-term success criteria called for establishment of a trend toward 75% cover for tree species and 45% cover for shrub species at the site (not specified for a particular plant association) measured over a 10-year period (annually until year 5 and biennially until year 10).

Because of contracting difficulties, monitoring reports for years 2 through 4 were submitted to the Corps together during year 4. Monitoring reports for years 2 through 4 indicated that the short-term success criteria were met by year 3 (1996) and that no further monitoring of percent survival would be performed. The monitoring reports submitted for year 6 (1999) indicated that the site was showing a trend toward satisfaction of the long-term success criteria. Other parameters measured at the site but not used to judge the site's overall success or failure indicated a trend toward successful establishment of riparian vegetation, as determined by an increase in the mean tree basal area and tree height. No information in the monitoring reports indicated the status of the site relative to species composition, plant vigor and health, natural reproduction, species diversity, or root development.

Hydrological evaluation of the site through 1996 indicated that flow frequency was maintained according to predicted models. Recent hydrological evaluations (1992 to 2000), however, indicate that the diversion channel has been dry since the spring of 1997 because of sediment deposits at the channel inlet as a result of high winter flows and overgrowth of

giant reed (Arundo donax) on the deposited sediment. Year 2000 monitoring is scheduled to be conducted on a biennial basis, and the inlet remains blocked, precluding flows from entering the diversion channel.

Introduction

The California Department of Transportation applied for a Department of the Army permit in 1991 to construct State Route 85, a new 18-mile-long 6-lane freeway in San Jose, California. The freeway was designed to link two existing highway corridors, Interstate 280 to the north and U.S. 101 to the south. The construction of State Route 85 resulted in impacts to nine creeks regulated by the Corps pursuant to Section 404 of the CWA. The impacts included construction of bridges over the creeks, construction of storm drain outfalls, realignment of creek channels, installation of hardscape erosion control measures such as rip rap and channel lining, placing fill into the creeks to facilitate widening, culverting flows beneath new sections of road, and installation of flood control facilities such as berms, flood walls, and check dams. The overall project resulted in the placement of approximately 7,600 yd3 of fill within Corps jurisdiction and impacted a total of 9 ac of riparian habitat.

Coyote Creek Mitigation

The Coyote Creek mitigation site is as an off-site mitigation area. It was designed to provide riparian woodland habitat common to California 's Santa Clara Valley, as partial replacement for riparian habitat impacts on nine creeks along the proposed State Route 85 corridor. The Coyote Creek mitigation site is located near U.S. 101 in San Jose, California.

The mitigation project required extensive reworking of the site's topography and hydrology and installation and establishment of large numbers of native riparian plant species. The mitigation site was designed to provide 24.4 ac of riparian habitat adjacent to Coyote Creek. Monitoring for the project was designed to assess the development of riparian habitat from the time of grading and plant installation until the project met or exceeded all success criteria or by mutual agreement between the California Department of Transportation and resource agencies (H.T.Harvey and Associates 1992).

In 1993, the mitigation site was graded and soil removed (approximately 10 to 15 ft deep) in an effort to bring the final grade closer to the groundwater table. In addition, a meandering 2,300-ft-long, 9-ft-wide, 2-ft-deep channel was constructed through the center of the site (USACOE 1991, Public Notice 18998S92). The channel was designed to carry water

diverted from Coyote Creek through two breaches in the adjacent levee. Once the diversion channel was created, the site was vegetated with four plant associations, including streamside, floodplain, valley oak forest, and slope communities. The streamside association extended 25 ft on each side of the channel and included willows and associated understory species. The floodplain association included an overstory of cottonwoods, a shrub layer of willows and blackberry, and an understory consisting of an herbaceous seed mix. The valley oak forest association included an overstory of valley oaks and an understory consisting of an herbaceous seed mix. The slope association included an overstory of sycamore, California walnut, and buckeye; a shrub layer of elderberry, toyon, coyote brush; and an understory consisting of an herbaceous seed mix.

Mitigation Monitoring Parameters and Success Criteria

The mitigation monitoring plan established short- and long-term success criteria, including percent survival and percent cover (H.T.Harvey and Associates 1992). Various other site evaluation parameters also were monitored; however, these parameters provided information about the site and did not constitute specific criteria on which the success of the site would be judged. These parameters included species composition, plant vigor and health, plant height, plant basal area, natural reproduction, species diversity, root development, photo documentation, and hydrological evaluation (frequency and extent of flow in the created channel and functioning of the created channel itself).

Short-Term Success Criterion

Percent survival formed the basis for establishment of the short-term success criterion. This criterion applies to survival of plants installed at the site and was broken down into two categories, including overall survival and cumulative survival. Overall survival includes that of original woody plants and plants installed to replace dead or dying original plantings. This criterion specifies successful accomplishment of this monitoring parameter when 80% survival of woody plants in the slope and valley oak associations is achieved and when 90% survival of woody plants in the floodplain and streamside plant associations is achieved. This parameter was designed to be measured for a period of 5 years after initial plant installation. Cumulative survival calculates the survival of original plantings only. This criterion specifies successful accomplishment of this monitoring parameter when 60% survival (original plantings only) of woody plants in the slope and valley oak associations is achieved and when 70% survival of woody plants in the floodplain and streamside

associations is achieved. This parameter was designed to be measured for a period of 5 years after initial plant installation.

Long-Term Success Criterion

Percent cover formed the basis for establishment of long-term success criterion. This criterion calls for achievement of a steady trend toward reaching the ultimate goal of 75% cover for trees and 45% cover for shrubs. The mitigation monitoring report indicated that after the fifth year, the percent cover by trees and shrubs would be monitored as the prime indicator of increasing habitat values. This parameter was designed to be measured for a 10-year period with yearly monitoring occurring through year 5 and biennial monitoring occurring thereafter until year 10.

Duration of Monitoring

The mitigation monitoring plan called for a 15-year monitoring period in which plant survival and species composition would be measured for a total of six consecutive years starting with year 0 (H.T.Harvey and Associates 1992). Plant vigor and health, plant height, basal area, natural reproduction and species diversity were to be monitored yearly through year 5 and every other year through year 10. Root development was to be monitored in years 3, 4, and 5, while hydrological monitoring and photo documentation of the site were to be carried out yearly for 15 consecutive years, including year 0.

Site Installation and Postinstallation Site Review

Grading, installation of water control structures, and planting took place at the Coyote Creek mitigation site from May through September 1993. A total of 10,484 container plants of riparian species were installed between May and June. Results from monitoring visits in September 1993 (year 0) indicated that insects, dust, drought, and browse damage were the most common plant damage factors, although it was noted that none were significantly impeding restoration efforts (H.T.Harvey and Associates 1993). Actions implemented to respond to the September 1993 monitoring results included weed control, mulch application, installation of foliage protectors, erosion control remedial measures, installation of groundwater monitoring systems, and insect/rodent abatement.

Mitigation Monitoring and Site Development

Due to funding and contracting issues associated with the California Department of Transportation, mitigation monitoring reports for 1994,

1995, and 1996 were not submitted until the spring of 1997. The results of the monitoring reports submitted for 1994 and 1995 indicated that the success criterion for vegetation was met in both years; however, results were inconclusive for success of the hydrological criterion, and the Department of Transportation recommended reevaluation of the hydrological criteria in conjunction with the Corps.

Monitoring conducted at the site in 1996 indicated that it continued to improve after cessation of irrigation in 1995. The 1996 monitoring report noted that the overall and cumulative success criteria goals had been met. As a result, subsequent monitoring reports would no longer document short-term success criterion parameters. Hydrologic monitoring was not performed.

Management recommendations for 1996 included the need to evaluate the system for collecting hydrological data, as well as performance of weed control along the perimeter of the site to reduce potential fire hazard, increasing monitoring for erosion control needs during the wet season and installation of remedial erosion control measures, and weed control throughout the site particularly for giant reed and water primrose (Ludwigia peploides), which were noted to cover approximately 60% of the site.

The 1997 monitoring report specified that, since the short-term success criterion had been achieved, measurements for this criterion were no longer taken at the site (California Department of Transportation 1997). The 1997 monitoring report showed that measurements taken at the site for percent cover (long-term success criterion) indicated that the site was continuing to show a steady trend toward reaching the ultimate goal of 75% cover for trees and 45% cover for shrubs (California Department of Transportation 1997). For the hydrological evaluation, the report noted that equipment installed on Coyote Creek to monitor flow frequency and the extent of flooding had not functioned since 1995 and was washed away during high flows in 1997. The report recommended that field observation with documented field notes and photographs be used to monitor flow frequency and stability of the diversion channel.

The monitoring report also noted that the diversion channel did not receive water from Coyote Creek throughout the monitoring period from spring through fall of 1997 (California Department of Transportation 1997). Field surveys to determine the cause of reduced flows revealed that sediment deposits had blocked the inlet to the diversion channel (California Department of Transportation 1998). In addition, in the general area of the weir inlet into the diversion channel, there was a massive growth of giant reed. The giant reed appears to have stabilized deposited sediments and assisted in blocking flow into the diversion channel. The monitoring report documents that the disruption of flows into the diversion channel

was predicted in the hydrological model developed for the site (California Department of Transportation 1998; H.T.Harvey and Associates 1990).

No monitoring was conducted in 1998 due to institution of biennial monitoring as per mitigation plan (H.T.Harvey and Associates 1992).

The year 1999 marked the start of biennial monitoring. Only the long-term success criterion was monitored since the short-term success criterion had been met in earlier monitoring years. Results of monitoring in 1999 indicated that the site was continuing to show a steady trend toward reaching the ultimate goal of 75% cover for trees and 45% cover for shrubs. Other parameters previously monitored, including species composition, plant vigor and health, basal area, natural reproduction, species diversity, and root development, were not monitored. Further, it was recommended in the monitoring report that only the percent cover criterion be evaluated in future reports since the “other vegetative parameters do not contribute information to the trend for percent cover which is the long-term success criterion for the site” (California Department of Transportation 2000). It was also recommended that the length of sampling be reduced such that all monitoring would be concluded by year 10 (2003) since the long-term success criterion (percent cover) only specifies monitoring through year 10 and it appears that the long-term success criterion will be met. The current schedule calls for monitoring on a biennial basis through 2008.

Visual hydrological evaluations in 1999 showed that the diversion channel had been successfully maintained “in that the extent and frequency of flow are comparable to the model” (California Department of Transportation 2000). The hydrology in the diversion channel was not considered successful in that the diversion channel appeared to have been dry since the spring of 1997. The monitoring cited another agency, the Santa Clara Valley Water District, as having mitigation plans involving Coyote Creek and that part of the mitigation involved removing the giant reed from the creek and dredging the inlet to restore flow to the diversion channel. These activities are expected to restore flow from Coyote Creek into the diversion channel. To date, the problem of flows being blocked at the diversion channel inlet has not been corrected.

California Department of Transportation. 1997. Annual Monitoring Report Army Corps Permit 18998S92.

California Department of Transportation. 1998. Annual Monitoring Report Route 85-Coyote Creek Mitigation Site at Bernal Road and Highway.

California Department of Transportation. 2000. Caltrans Route 85-Coyote Creek Mitigation Monitoring Report for 1999

H.T.Harvey & Associates. 1990. Route 85-Coyote Creek Mitigation Conceptual Revegetation Plan, 2nd Rev. Prepared for the California Department of Transportation, Oakland, CA. October 18, 1990.

H.T.Harvey & Associates. 1992. Final Approved Route 85-Coyote Creek Mitigation Project Site Performance Monitoring Plan. File 449–09. H.T.Harvey & Associates.

H.T.Harvey & Associates. 1993. Route 85-Coyote Creek Mitigation Site 1993 Annual Monitoring Report. Project No. 449–15. H.T.Harvey & Associates.

NORTH CAROLINA WETLANDS RESTORATION PROGRAM

The North Carolina Wetlands Restoration Program (NCWRP) was established by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1996. The purpose of the NCWRP is to restore, enhance, preserve, and create wetlands, streams, and riparian areas throughout the state's 17 major river basins. The goals of the program are to restore functions and values lost through historic, current, and future wetland impacts; to achieve a net increase in wetland acres, functions, and values in all of North Carolina's major river basins; to provide a consistent and simplified approach to address mitigation requirements associated with permits or authorizations issued by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers (Corps); and to increase the ecological effectiveness of required wetland mitigation and promote a comprehensive approach to the protection of natural resources.

The NCWRP established that all “compensatory mitigation” in North Carolina required as a condition of a Section 404 permit or authorization issued by the Corps be coordinated by the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) consistent with basinwide plans for wetland restoration and rules developed by the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission (EMC). All compensatory wetland mitigation, whether performed by DENR or by permit applicants, shall be consistent with basinwide restoration plans. The emphasis of mitigation is expressly on replacing targeted functions in the same river basin (but not necessarily on in-kind or on-site mitigation) unless it can be demonstrated that restoration of other areas outside the impacted river basin would be more beneficial to the overall purposes of the wetlands restoration program.

Development and implementation of basinwide wetland and riparian restoration plans for each of the state's 17 river basins was a statutory mandate of the program. A key component of the basinwide approach is development of local watershed plans (LWPs) to protect and enhance water quality, flood prevention, fisheries, wildlife habitat, and recreational opportunities in each of the 17 river basins. LWPs are developed cooperatively with representatives of local governments, nonprofit organizations, and local communities. They provide an opportunity for local stakeholders, including residents, community groups, businesses, and industry, to

play a role in shaping the future of their watershed. The NCWRP then utilizes the Basinwide Wetlands and Riparian Restoration Plans to target and prioritize degraded wetland and riparian areas, which, if restored, could contribute significantly to the goal of protecting and enhancing watershed functions.

The rational for focusing NCWRP restoration resources in priority watersheds was based on two assumptions. First, it was assumed that, although most watersheds in the state could benefit from wetlands and riparian area restoration, restoration may be more effective, efficient, and feasible in certain watersheds. Second, some watersheds need restoration sooner than others in order to either preserve their threatened natural resources or improve their degraded status before it becomes too late to make a difference. Prioritizing watersheds based on restoration feasibility and the critical nature of restoration needs helps to ensure that resources are used in the most efficient manner to maximize achievement of program goals.

An applicant may satisfy compensatory wetland mitigation requirements by the following actions, provided those actions are consistent with the basinwide restoration plans and also meet or exceed the requirements of the Corps: payment of a fee established by DENR into the Wetlands Restoration Fund (WRF); donation of land to the Wetlands Restoration Program (WRP) or to other public or private nonprofit conservation organizations as approved by DENR; participation in a private wetland mitigation bank; and preparing and implementing a wetland restoration plan.

The WRF was established as a nonreverting fund within DENR and was seeded with a $6 million appropriation from the Clean Water Management Trust Fund and $2.5 million annually from the North Carolina Department of Transportation for a period of 7 years for the development of LWPs. The WRF provides a repository for monetary contributions and donations or dedications of interests in real property to promote projects for the restoration, enhancement, preservation, or creation of wetlands and riparian areas and for payments made in lieu of compensatory mitigation. Funds expended from the WRF for any purpose must be in accordance with the basinwide plan and contribute directly to the acquisition, perpetual maintenance, enhancement, restoration, or creation of wetlands and riparian areas, including the cost of restoration planning, long-term monitoring, and maintenance of restored areas. Monetary fees to the WRF are established by the EMC on a standardized schedule on a per-acre basis based on ecological functions and values of wetlands permitted to be lost.

The DENR must report each year by November 1 to the Environmental Review Commission regarding its progress in implementing the WRP and its use of monies in the WRF. The report must document statewide

wetland losses and gains and compensatory mitigation. The report must also provide an accounting of receipts and disbursements of the WRF, an analysis of the per-acre cost of wetlands restoration, and a cost comparison on a per-acre basis between the NCWRP and private mitigation banks.

The Basinwide Wetlands and Riparian Restoration Plan contains the following information: a statement of the restoration goals for each river basin; a map of each priority subbasin showing water-quality information, watershed boundaries, and land cover by type (agricultural, forested, or developed); a narrative overview of the river basin, including general information on existing water-quality-related problems; summary information on natural resources; descriptions of each priority subbasin; and data on wetland impacts.

The NCWRP completed all 17 basinwide wetlands and riparian restoration plans in 1998. Update plans are scheduled to be reviewed and revised in accordance with the Division of Water Quality's 5-year revision schedule for basinwide water-quality plans. LWPs are currently being developed. Since execution of the first contract in 1998, the NCWRP has 37 restoration projects in different stages of development that together will restore an estimated 61 ac of wetlands and 99,637 linear feet of stream and 219 ac of streamside buffers. The NCWRP is in its infancy, and implementation of projects is relatively recent. Little success of restoration targeted wetland functions has yet to be quantified on any project; however, development of basinwide wetland and riparian restoration plans, local watershed plans, and implementation of restoration projects is proceeding on schedule.