4

Wetland Permitting: History and Overview

This chapter describes the evolution of compensatory mitigation requirements in the Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 404 program, including agency guidance on the use of mitigation banks and in-lieu fees. Also noted is the somewhat limited role that CWA compensatory mitigation plays in the attempt to achieve no net loss of the nation's remaining wetland base. The chapter concludes with a brief overview of the CWA Section 404 permitting process.

EVOLUTION OF COMPENSATORY MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS IN THE CWA SECTION 404 PROGRAM

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) makes its decisions regarding mitigation requirements within a framework of multiple statutes, regulations, guidance, and policy documents (see Box 4–1). These provisions include general mitigation requirements (i.e., ones that derive from sources other than the CWA and that may apply to all federal agencies in general); general Corps policies for evaluating permit applications (i.e., requirements that apply to all permit programs the Corps administers); and CWA-specific mitigation requirements (i.e., obligations that apply solely in the Section 404 context and that flow from the CWA, the Section 404(b)(1) guidelines, and policy documents). After examining these requirements, agency guidance regarding the use of mitigation banks and in-lieu fees is reviewed.

|

BOX 4–1 Timeline of Significant Federal Actions Regarding Wetland Permit and Mitigation Requirements |

|

|

1890s |

Rivers and Harbors Act enacted (the earliest regulation of activities in waters of the United States) |

|

1934 |

Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act enacted |

|

1968 |

Corps Public Interest Review promulgated |

|

1969 |

National Environmental Policy Act enacted |

|

1972 |

Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) enacted |

|

1973 |

Endangered Species Act enacted |

|

1975 |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Section 404(b)(1) Guidelines Promulgated |

|

1977 |

FWPCA amended (as Clean Water Act) |

|

1980 |

EPA Section 404(b)(1) Guidelines revised |

|

1990 |

U.S. Congress instructs the Corps to pursue the goal of “no overall net loss” (Section 307, Water Resources Development Act) |

|

1990 |

Corps and EPA mitigation Memorandum of Agreement calls for sequencing and establishes preferences for on-site, in-kind mitigation |

|

1993 |

Corps and EPA Joint Memorandum (Interim Guidance) on Mitigation Banking issued |

|

1995 |

Interagency Mitigation Banking Guidance issued |

|

1998 |

Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century enacted, expressing congressional preference that mitigation for highway projects be supplied by mitigation banks |

|

2000 |

In-Lieu Fee Guidance issued |

GENERAL MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS

Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act

Mitigation to offset the impacts of dredging and filling projects is not a new concept for the federal government. Indeed, in 1934 the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act required federal agencies that construct or permit dams to consult with the then-existing Bureau of Fisheries to make provisions for fish migration (Public Law 73 –121). Subsequent amendments to the act now require federal agencies that engage in or permit projects that modify bodies of water to consult about habitat loss with the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Thus, prior to making Section 404 permit decisions, the Corps must discuss with the FWS a proposal's impact on wildlife resources. The act calls on the FWS to advise federal agencies about proposed projects ' impacts on fish and wildlife habitats and to recommend compensatory mitigation measures. Agencies are not, however, required to follow the FWS's recommendations (Sierra Club v. Alexander, 484 F. Supp. 455 (D.C.N.Y. 1980)).

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA)

The NEPA also requires federal agencies to consider mitigation measures before taking action, including the granting of federal permits, that may have adverse environmental consequences (Public Law 91– 190). The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), which is responsible for overseeing federal compliance with the NEPA, has promulgated regulations that are binding on federal agencies (40 CFR §§ 1500–1517 (2000)). CEQ defines mitigation to include (a) avoiding the impact altogether by not taking a certain action or parts of an action; (b) minimizing impacts by limiting the degree or magnitude of the action and its implementation; (c) rectifying the impact by repairing, rehabilitating, or restoring the affected environment; (d) reducing or eliminating the impact over time by preservation and maintenance operations during the life of the action; and (e) compensating for the impact by replacing or providing substitute resources or environments.

The Corps must discuss mitigation options in its NEPA documentation when examining alternatives to the proposed action. Similar to the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, NEPA largely imposes procedural requirements. Accordingly, federal agencies must consider the need for mitigation to compensate for federal actions (including the granting of a permit), but NEPA does not mandate that the agencies perform or require mitigation (Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council, 490 U.S. 332 (1989)).

Endangered Species Act (ESA)

In contrast to the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act and the NEPA, the ESA has more substantive mitigation requirements (Public Law 93– 205, as amended). For example, when a federal agency proposes to take an action (including the granting of a permit), the agency may need to consult with the FWS or the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to ensure that the proposed action will not violate the ESA. After consultation, the FWS or NMFS may issue a biological opinion that contains “reasonable and prudent alternatives” that the agency must follow to comply with the ESA. Additionally, any ESA permit that authorizes the taking of a protected species must specify how the applicant will “minimize and mitigate the impacts of such taking.”

Food Security Act (FSA)

Although the mitigation requirements of the FSA are limited to agricultural activities and are not directly applicable to the CWA Section 404 program, they deserve some mention. To discourage farmers from con-

verting wetlands into agricultural areas, the FSA, through its swampbuster program, penalizes landowners who plant agricultural commodities in converted wetlands (Strand 1997). Such landowners may become ineligible for certain federal agricultural loans and payments. A landowner may retain eligibility for federal benefits, however, by performing compensatory mitigation: restoring, enhancing, or creating wetlands. The FSA presumes that the mitigation will be provided on “a 1-for-1 acreage basis,” although more mitigation may be required if needed to offset lost wetland functions and values (Public Law 104–127). The FSA requires that such mitigation be “in the same general area of the local watershed as the converted wetland” and that a conservation easement be placed on the mitigation site.

GENERAL CORPS MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS

Long before assuming its responsibilities under the CWA, the Corps administered a regulatory program under the Rivers and Harbors Acts (RHAs) of 1890 and 1899 for work conducted in traditionally navigable waters (Strand 1997). For example, Section 10 of the RHA of 1899 declared excavating or filling such waters to be illegal without a Corps permit. For many years the Corps based its permit decisions “primarily upon the effect of the proposed work on navigation.” Environmental impacts were generally not considered.

In 1967 the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of the Army entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that articulated how the Corps would implement its obligation to consult with the FWS under the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act when it made its RHA decisions regarding dredging, filling, excavating, and other related work in traditionally navigable waters (Fed. Regist. 33(Dec. 18):18672–18673). The MOU recognized that permits to conduct work in these waters may, as a result of the consultation, include conditions the Corps determined “to be in the public interest.”

The following year the Corps codified the MOU in its regulations and announced a significant shift in its RHA permit decision criteria (Fed. Regist. 33(Dec. 18):18671). Rather than focusing on navigational impacts, the Corps would now evaluate “all relevant factors, including the effect of the proposed work on navigation, fish and wildlife, conservation, pollution, aesthetics, ecology, and the general public interest.” Under this public-interest review, the Corps could deny RHA permit applications based on environmental impacts or impose permit conditions to alleviate those impacts. Courts subsequently affirmed the Corps's authority to consider the environmental impacts of its permitting decisions (Zabel v. Tabb, 430 F.2d 199 (1971)).

In 1977 revisions to its regulations (by which time the Corps had assumed CWA Section 404 responsibilities), the Corps again noted its obligation to consult with the FWS under the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (Fed. Regist. 42(July 19):37137). The regulations also expressly provided that an “applicant will be urged to modify his proposal to eliminate or mitigate any damage to such [fish and wildlife] resources, and in appropriate cases the permit may be conditioned to accomplish this purpose.” In 1982 the Corps's regulations expanded the authority to add conditions when necessary to satisfy a legal requirement (e.g., the ESA) or to meet a public-interest objective, which now encompassed all environmental impacts (Fed. Regist. 47(July 22):31794). The last significant revision to the Corps's general mitigation policies occurred in 1986 when the Corps emphasized that if a permit applicant declined to provide compensatory mitigation needed to ensure that the project was not contrary to the public interest, the district engineer must deny the permit (Fed. Regist. 51 (Nov. 13):41206). Furthermore, the Corps pointed out that this general statement of mitigation policy was separate from and did not supercede any compensatory mitigation required by the CWA Section 404(b)(1) guidelines.

The factors that the Corps now considers in its public-interest review are found at 33 CFR 320.4. In its review, the Corps must specifically evaluate the proposed activity's likely effect on wetlands. See Appendix I for a list of the factors that the Corps must take into account in its permit decision-making process.

CWA SECTION 404 MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS

The terms “mitigate” and “mitigation” do not appear in CWA Section 404. Nor does Section 404 expressly authorize the Corps to require mitigation of permit applicants. Nevertheless, by virtue of the interplay between Sections 404(b)(1) and 403(c), the statute does provide implicit authority for the Corps to require permit applicants to avoid and minimize wetland impacts. Section 404(b)(1) requires EPA, in conjunction with the Corps, to develop the criteria that the Corps uses in its Section 404 permit decisions. These criteria, known as the 404(b)(1) guidelines, must be based on criteria identified in CWA Section 403(c). These criteria are applicable to ocean-based discharges (Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Public Law 92– 500)). Section 403(c) requires consideration of alternative disposal sites, including land-based sites, and minimization of adverse environmental impacts. Accordingly, EPA's Section 404(b)(1) guidelines must also consider alternatives (i.e., avoidance) and minimization of unavoidable impacts.

The EPA issued its Section 404(b)(1) guidelines in 1975 (Fed. Regist. 40(Sept. 5):41292–41298)). In their first iteration the guidelines stressed the need to avoid wetland impacts. If no less environmentally damaging prac-ticable alternative existed and if a project would not cause unacceptable adverse impacts on aquatic resources, the Corps could issue a permit. The guidelines also called for the impacts of a permitted project to be minimized. No mention was made of restoration, enhancement, or creation of wetlands, although the 1975 guidelines stated that “[c]onsideration shall be given to preservation of submersed and emergent vegetation.”

The current Section 404(b)(1) guidelines, promulgated in 1980, reaffirmed the avoidance and minimization requirements in greater detail (Fed. Regist. 45(Dec. 24):85336–85357). Subpart H (230.70–77) describes a number of actions that the Corps should consider as permit conditions to minimize adverse effects—for example, actions concerning the location of discharge, composition of discharge material, control of material after discharge, method of dispersal, and use of appropriate equipment and technology. Included in the minimization discussion is a reference to compensatory mitigation: “Habitat development and restoration techniques can be used to minimize adverse impacts and to compensate for destroyed habitat.” Thus, in the Section 404(b)(1) guidelines, compensatory mitigation, such as the restoration of wetlands, is a subset of minimization.

Additional support for compensatory mitigation can also be found elsewhere in the Section 404(b)(1) guidelines. The guidelines require that a permitted activity not cause or contribute to significant degradation of the waters of the United States, either individually or cumulatively. When determining whether a proposed activity will result in significant degradation, the Corps will consider to what extent compensatory mitigation will offset the activity's adverse effects.

The Section 404(b)(1) guidelines were developed in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act's public notice and comment procedures and are binding regulations that appear in the Code of Federal Regulations. Frequently, agencies turn to less formal documents, such as MOAs or regulatory guidance letters (which are typically not subjected to public notice and comment) to interpret the requirements of the CWA and the Section 404(b)(1) guidelines (Gardner 1991). These documents are issued to provide guidance to agency personnel and the public to explain how the agencies intend to apply the statute and regulations in the field. Much of the detail of the mitigation policies for the Section 404 program is found in these guidance documents.

A 1990 MOA between EPA and the Department of the Army explains how mitigation determinations should be made (Fed. Regist. 55(Mar. 12):9210). The MOA notes that the mitigation requirements of CEQ's regu-

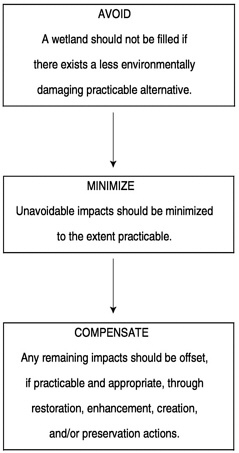

lation and the CWA Section 404(b)(1) guidelines are compatible and, as a practical matter, may be condensed to three general types of mitigation: avoidance, minimization, and compensatory mitigation (see Figure 4–1). The MOA emphasizes that this mitigation must be applied in a sequential fashion: an applicant must first avoid wetlands to the extent practicable; then minimize unavoidable impacts; and, finally, compensate for any remaining impacts through restoration, enhancement, creation, or, in exceptional cases, preservation. With respect to compensatory mitigation, the MOA expresses a preference for on-site, in-kind mitigation, with restoration as the first option considered.

The Corps and EPA mitigation MOA's sequencing requirement is limited in several important respects. First, the MOA applies only to individual permits, not general permits such as nationwide permits. Significantly, the Corps has reported that up to 85% of authorized projects in waters of the United States proceed under a general permit (Davis 1997).

FIGURE 4–1 Mitigation sequencing.

Second, subsequent guidance documents have relaxed the rigorousness of the avoidance requirement for individual permits when the wetland impact site is of low environmental value or when the permit applicant is a small landowner (Fed. Regist. 65(Mar. 9):12518–12519).

MITIGATION BANKING

The Corps and EPA define a mitigation bank as “a site where wetlands and/or other aquatic resources are restored, created, enhanced, or in exceptional circumstances, preserved expressly for the purpose of providing compensatory mitigation in advance of authorized impacts to similar resources” (Fed. Regist. 60 (Nov. 28):58605). Mitigation banks provide off-site mitigation. Mitigation banks may be established by permittees who anticipate having a number of future permit applications or by third parties who develop wetland credits for sale to permittees needing to provide compensatory mitigation. Although the Corps and EPA MOA expressed the agencies' preference for on-site compensatory mitigation, it does acknowledge that “[m]itigation banking may be an acceptable form of compensatory mitigation under specific criteria designed to ensure an environmentally successful bank.” The Corps and EPA MOA promised additional guidance on mitigation banking; that was forthcoming in the form of a Corps and EPA joint memorandum to the field issued in 1993.

The 1993 memorandum announced interim national guidance for mitigation banking in the Section 404 program (Fed. Regist. 60(Mar. 14):13711, also Corps Regulatory Guidance Letter 93–02). The interim guidance identified several benefits of relying on mitigation banks rather than individual mitigation projects. First, because mitigation is done in advance of project impacts, it reduces “temporal losses of wetland functions and uncertainty over whether the mitigation will be successful in offsetting wetland losses.” Second, the agencies suggested that it may be ecologically advantageous to have consolidated mitigation sites instead of smaller isolated projects. Third, the agencies believed that mitigation banks were more likely to marshal together the financial resources and scientific expertise necessary for effective mitigation projects. Fourth, the guidance also stated that the economies of scale resulting from mitigation banks should lead to “cost-effective compensatory mitigation opportunities” for permit applicants. The guidance emphasized that mitigation banks could provide compensatory mitigation only and thus could be available to offset wetland impacts only where the permit applicant had complied with the sequencing requirement (i.e., avoid first, then minimize impacts before compensating).

The 1993 interim national guidance explained that the Corps, EPA, and other relevant agencies should enter into an agreement with the en-

tity establishing the bank. Such agreements should address the bank 's location, its goals and objectives, the bank's sponsor and participants, a development and maintenance plan, an evaluation and assessment methodology, procedures for crediting and debiting mitigation gains, the geographic service area, monitoring provisions, remedial actions, and long-term protection of the site. The interim guidance authorized the establishment and use of third-party banks (i.e., banks operated by entities other than the permittee, such as an entrepreneurial bank) but noted that permittees must remain legally responsible for ensuring mitigation compliance.

In 1995 the Corps, EPA, FWS, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) published interagency federal guidance on the establishment, use, and operation of mitigation banks (Fed. Regist. 60(Nov. 28):58605). The 1995 guidance, which supplanted the Corps and EPA's 1993 interim guidance, was subjected to public notice and comment prior to its issuance. Nevertheless, the preamble to the 1995 guidance notes that it is an interpretive rule and not a regulation that has the force of law.

The 1995 guidance identified two additional benefits that mitigation banking offers. First, consolidation of mitigation at a bank makes agency compliance monitoring more effective. Rather than visiting many individual mitigation sites, a regulator need visit only a single bank site. Second, the agencies suggested that the availability of mitigation banks could make compensatory mitigation appropriate and practicable in cases where the Corps had not previously required any compensatory mitigation, especially for authorized activities under general permits. In this way, the agencies reasoned, mitigation banking could contribute to the attainment of the goal of no net loss of wetlands.

The 1995 guidance elaborated on the mitigation banking approval process in greater detail. To initiate the process, the bank sponsor, the entity responsible for establishing the bank, should submit a prospectus to the Corps. The prospectus is a document that describes the bank sponsor's proposal on how the bank will be established and operated. An interagency group, the Mitigation Banking Review Team (MBRT), which may consist of representatives from federal, state, tribal, and local agencies, reviews the proposal. For mitigation banks in the Section 404 program, the Corps representative serves as MBRT chair.

The MBRT review process may lead to the development of a formal agreement, the banking instrument. The 1995 guidance expands on the 1993 interim guidance with respect to what information should be included in a banking instrument: ownership of the bank site; bank size and types of wetland classes that will be included in the bank, with a site plan and specifications; a description of the baseline (existing) conditions at

the bank site; wetland impacts suitable for compensation; financial assurances; and compensation ratios. The 1995 guidance also provides greater detail about the timing of credit withdrawal and financial assurances. For example, the guidance allows limited early withdrawals of mitigation credit prior to meeting mitigation performance standards. The guidance cautions, however, that early withdrawals should be done only when there is a high likelihood that the bank will achieve its requirements. Furthermore, the MBRT must have approved the banking instrument and plans; the bank site must have been secured; the bank sponsor must have provided financial assurances (e.g., performance bonds and escrow accounts); initial physical and biological work must be finished no later than the first full growing season after the early withdrawals; and the banking instrument may impose higher compensation ratios.

With respect to financial assurances, the 1995 guidance states that a bank sponsor should secure sufficient funds for remedial actions in the event that the mitigation project fails or founders. Moreover, the bank sponsor must provide financial assurances for monitoring and maintaining the bank through its operational life (while the credits are generated and debited) and for long-term monitoring and maintenance. Most significantly, the 1995 guidance also shifts legal responsibility for compliance of the mitigation site from the permittee to the bank sponsor.

In 1998, Congress expressed its preference that mitigation banks be used to offset wetland impacts from federally funded transportation projects (Public Law 105–178). The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century states that the Corps shall give mitigation banks preference “to the maximum extent practicable,” if banks are approved in accordance with the 1995 guidance and sufficient credits are available.

IN-LIEU FEES

In addition to authorizing individual mitigation projects and mitigation banks to satisfy a permittee's compensatory mitigation obligation, the Corps has sanctioned the use of in-lieu fee mitigation. The Corps and EPA define an in-lieu fee as a payment “to a natural resource management entity for implementation of either specific or general wetland or other aquatic resource development projects, [which] …do not typically provide compensatory mitigation in advance of project impacts” (Fed. Regist. 60(Nov. 28):58605). In the 1995 guidance on mitigation banking, the agencies suggested that the sponsor of an in-lieu fee account should enter into an agreement, “similar to a banking instrument,” to define the conditions when in-lieu fee mitigation is appropriate.

For several years after the 1995 mitigation banking guidance, policy statements about the use of in-lieu fees appeared in the Federal Register in

the Corps's preamble discussion regarding its nationwide permit program. Traditionally, the Corps did not require any compensatory mitigation to offset the impacts of activities authorized by nationwide permits (NWPs). In 1996, however, the Corps concluded that compensatory mitigation may be appropriate for some NWPs; permittees could satisfy the mitigation requirement through credits from mitigation banks or in-lieu fee payments “to organizations such as The Nature Conservancy, state or county natural resource management agencies, where such fees contribute to the restoration, creation, replacement, enhancement, or preservation of wetlands” (Fed. Regist. 61(Dec. 13):65874–65922). In a 2000 notice in the Federal Register, the Corps expressed its preference that compensatory mitigation for NWPs come from consolidated mitigation approaches, which include mitigation banks and in-lieu fees (Fed. Regist. 65(Mar. 9):12818 – 12899). At that time, however, the Corps declined to express a preference between mitigation banks and in-lieu fee arrangements.

In November 2000 the Corps, EPA, FWS, and NOAA issued interagency guidance on the use of in-lieu fees to offset wetland fill impacts (Fed. Regist. 65(Nov. 7):66914). That guidance reiterated the Corps and EPA mitigation MOA preference for on-site, in-kind mitigation but recognized that such mitigation may not always be available, practicable, or environmentally preferable. With respect to compensating for impacts from individual permits, the guidance provides that in-lieu fee arrangements may be used if there is a formal agreement that is developed, reviewed, and approved through the interagency MBRT process.

For impacts from general permits, the 2000 guidance offers more detail. As a general rule, the agencies prefer on-site mitigation to off-site mitigation. When, however, off-site mitigation is permitted, the agencies state that the “use of a mitigation bank is preferable to in-lieu fee mitigation where permitted impacts are within the service area of a mitigation bank approved to sell mitigation credits, and those credits are available.” The preference for mitigation banks does not apply when (1) the mitigation bank does not provide in-kind mitigation and the in-lieu fee arrangement offers in-kind restoration, or (2) the mitigation bank provides only preservation credits and the in-lieu fee arrangement offers in-kind restoration. The 2000 guidance requires that in-lieu fee sponsors who wish to offset impacts from activities authorized by general permits enter into a formal agreement with the Corps. The in-lieu fee agreement should contain provisions very similar to those in mitigation banking agreements.

THE CLEAN WATER ACT AND THE GOAL OF NO NET LOSS

The CWA vests the Corps (or a state with an EPA-approved program) with the authority to issue a Section 404 permit and to decide whether to

attach conditions. Section 404 permit conditions may include a requirement to provide compensatory mitigation. However, it is important to note how the Corps and EPA—the federal agencies charged with administration of the CWA Section 404 program—interpret the program's goals.

The agencies state that a goal of the program is to seek no overall net loss of wetland functions and values (Fed. Regist. 55(Mar. 12):9210). The no-net-loss goal is a statement of policy or an interpretive rule that the agencies articulated in their 1990 mitigation MOA. Congress subsequently established, through the Water Resources Development Act of 1990, a no-net-loss goal for the Corps's water resources development program. However, the no-net-loss goal does not appear in Corps or EPA regulations, and the statutory goal does not specifically apply to the Corps's regulatory program.

In the 1990 mitigation MOA, the Corps and EPA recognize that no net loss may not be satisfied in every Section 404 permit action but emphasize that a goal of the CWA Section 404 program “is to contribute to the national goal of no overall net loss of the nation's remaining wetland base.” Thus, the agencies acknowledge two important limitations of the CWA Section 404 program with respect to wetland mitigation. First, the program is not designed to remedy historical losses of wetlands; rather, it focuses on existing or remaining wetland functions and values. Second, the program is not expected to achieve the goal of no net loss of existing wetland functions and values by itself. Accordingly, before examining the permit process and the technical aspects of wetland mitigation, it may be instructive to consider the somewhat limited role that wetland mitigation in the CWA Section 404 program plays in efforts to achieve the goal of no net loss.

The CWA does not vest the federal government with the authority to assert jurisdiction over all wetlands and all wetland-damaging activities. The geographic scope of the CWA is limited by two main sources: the language of the CWA itself and the U.S. Constitution. The CWA provides the Corps with jurisdiction over “waters of the United States.” The Corps had interpreted this phrase to include isolated waters, including isolated wetlands, that provided habitat to migratory birds. In Solid Waste Agency of Northern Cook County v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Corps's “migratory bird rule” was an unreasonable reading of the plain language of the CWA. The Supreme Court's decision leaves open the possibility that Congress may amend the CWA to make it clear that the act should regulate activities in isolated waters, including isolated wetlands. If Congress chooses to do so, however, the decision suggests that such an exercise of federal power may be constitutionally suspect unless there is a sufficient nexus to Congress's power over interstate commerce.

Regardless of where the line is drawn for geographic jurisdiction, another limitation of the CWA Section 404 program concerns activities that trigger a permit (and perhaps a mitigation) requirement. Jurisdiction of the CWA Section 404 program is activity specific; the program only regulates the discharge of dredged or fill material (Want 1994). Agencies have no CWA jurisdiction over other activities that destroy wetlands. Some activities that result in wetland impacts are not regulated by the Section 404 program and thus are not subject to its mitigation requirements. For example, the mere draining of a wetland does not trigger Section 404. Nor may the Corps require a permit for draining, dredging, or excavation activities that result in only incidental fallback of dredged material (National Mining Association v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 145 F.3d 1399 (D.C. Cir. 1998)). While it may be difficult and expensive for developers to excavate and drain wetlands in a manner that avoids triggering Section 404, it is technically feasible for a developer to legally drain hundreds of acres of wetlands outside the scope of the CWA. Indeed, the case that prompted the Corps to issue the so-called Tulloch rule involved the draining of approximately 700 acres of pocosin wetlands in North Carolina (Gardner 1998). Moreover, even some activities that constitute the discharge of dredged or fill material are not subject to CWA regulation because of the statutory exemption for normal agricultural, silvicultural, and ranching activities. The Corps is not required to report losses on activities they do not regulate; therefore, loss of these wetlands from such unregulated activities does not figure into the Corps's calculations when it declares that it requires more acres in mitigation than it permits to be filled.

Even if an activity is regulated by CWA Section 404, that fact alone does not lead to the conclusion that mitigation will be required to offset the loss of functions and values. As will be explained in more detail below, the Corps issues two types of Section 404 permits: individual permits and general permits. Individual permits, which include standard permits, are issued on a case-by-case basis. Applications for activities that require a standard permit are subjected to more rigorous review, and the sequencing requirement may apply. The Corps must issue a public notice prior to making its permit decision and must decide what level of compensatory mitigation, if any, is appropriate in each particular case. The Corps and EPA report that approximately 15% of activities authorized under the Section 404 program proceed under an individual permit; most activities are authorized by general permit (Davis 1997). Section 404 authorizes the Corps to issue general permits (which may be nationwide permits, regional permits, or programmatic permits) for any category of activity, if the activity will cause only minimal individual and cumulative adverse environmental impacts (Strand 1997). In contrast to individual

permits, general permits authorize activities to occur in wetlands with little agency oversight. Indeed, some activities authorized by general permit allow the permittee to proceed without notifying the Corps. Initially, the Corps required little or no compensatory mitigation to offset wetland impacts for activities authorized by general permit (33 CFR Parts 320–330, Nov. 13, 1986). Significant changes, however, have been implemented in the permitting program. First, the types of activities and size of fill eligible for a general permit have been limited. As a result, more fills require individual permits and permit recipients are expected to provide compensatory mitigation. Second, the Corps now more frequently imposes compensatory mitigation requirements for general permits.

In sum, some isolated wetlands are beyond the scope of the Section 404 program. Moreover, some wetland-damaging activities are not subject to CWA Section 404 regulation. Most activities that do trigger Section 404 are authorized by general permit and thus may not require compensatory mitigation. For those activities that require an individual Section 404 permit, however, the Corps frequently imposes a compensatory mitigation condition. It should be noted that the Section 404 program may lessen impacts to the aquatic environment better than would occur with no such requirements, because developers are encouraged to avoid or reduce impacts through the sequencing process of individual permit requirements or by further reducing project impacts to allow use of the simpler general permit program (33 CFR Parts 320–330, Nov. 13, 1986). The data presented and the discussion of those data in Chapter 1 illustrate this possibility.

SECTION 404 PERMIT PROCESS

Section 404 of the CWA authorizes the Department of the Army to issue permits for discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States, including wetlands. The Corps categorizes Section 404 permits as either standard or general permits. Individual permits include standard permits and letters of permission, while general permits include regional permits, nationwide permits, and programmatic permits for projects that should result in only minimal impacts to the aquatic environment.

Standard Permits

The most common form of individual permit is the standard permit. Standard permits are issued after a “case by case evaluation of a specific project involving the proposed discharges in accordance with the procedures of this part and 33 CFR part 325 and determination that the pro-

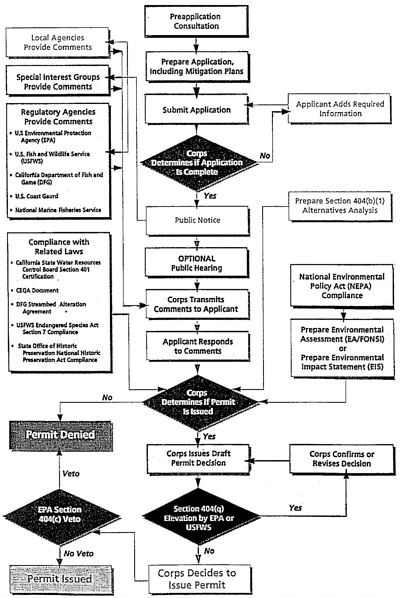

posed discharge is in the public interest pursuant to 33 CFR part 320” (Fed. Regist. 51(Nov. 13):41206). A review of an individual permit application may include a preapplication meeting in which the Corps and other resource agencies meet with the applicant and discuss the project. Preapplication meetings can help streamline the permitting process by alerting the applicant to potentially time-consuming concerns that are likely to arise during the project evaluation. Figure 4–2 illustrates of the complexities of the Section 404 process for California.

Upon receipt of an application, Corps staff have 15 days to determine if it is complete (33 CFR 325.1(d)), and staff must contact the applicant within the 15-day time period if additional information is necessary. Once an application is deemed complete, the next step is to determine what form of permit review is appropriate for the proposed project and to issue a public notice within 15 days. The Corps then considers public comments on the notice. The district engineer may determine that a public hearing is necessary when it would provide additional information not otherwise available that would enable a thorough evaluation of pertinent issues.

An integral part of the individual permit application process is the analysis required for evaluating compliance with Section 404(b)(1) guidelines and their sequencing requirement, as discussed earlier. The project must also be evaluated to ensure that it is not contrary to the “public interest” (33 CFR Part 320.4). At the same time, the Corps prepares its documentation pursuant to NEPA.

To assist with its internal evaluations, the Corps consults with the FWS pursuant to the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act. The Corps may also be required to initiate consultation with the FWS and/or NMFS for project impacts to species or habitat protected under the ESA. For the purpose of evaluating permit applications, the Corps considers the scope of analysis under ESA to be limited to the boundaries of the permit area plus any additional area outside Corps jurisdiction where there is sufficient federal control and responsibility (USACE 1999a).

The Corps makes its decision to authorize or deny the permit application based on its evaluation of the data collected. If a proposed project does not satisfy Section 404(b)(1) guidelines, the Corps must deny a permit. Similarly, if the proposed project is not in the public interest or would violate the ESA, the Corps must deny a permit. Although many proposed projects are modified through the permit process, most permit applicants receive Corps approval (Davis 1995). That authorization, however, may contain conditions pertaining to compensatory mitigation. Under the Corps's administrative appeals process, once a standard permit is issued, its terms and conditions may be appealed to the division engineer.

General Permits

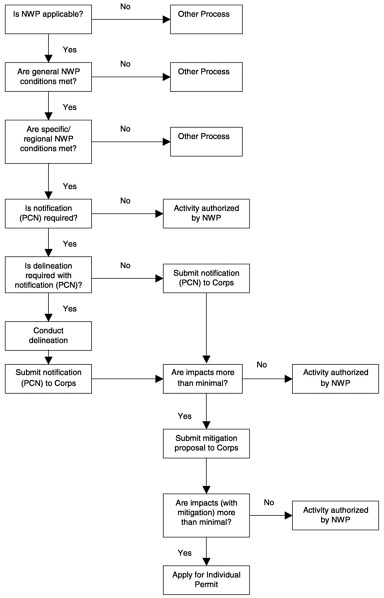

The most commonly used form of general permit is the nationwide permit (NWP). Like all general permits, NWPs are issued for classes of activities that should result in only minimal individual and cumulative adverse effects to the aquatic environment (Long et al. 1992). The Corps publishes proposed NWPs for public comment in the Federal Register and considers input from the public before deciding to issue an NWP. Initially, the Corps published a list of current NWPs in an appendix to 33 CFR Part 330 but no longer does so. Instead, current NWPs are available at the Corps district offices and may be found on the Corps website at www.usace.army.mil. Figure 4–3 illustrates how the NWP process operates.

The term “minimal,” as it is used in the CWA and regulations, is not quantified, leaving the determination of what constitutes a minimal impact to the interpretation of the Corps regulatory staff. The thresholds in the NWP program provide some guidance as to what level of impact the Corps considers acceptable, and this threshold has become increasingly lower since the program was first authorized. For example, NWPs authorized on November 22, 1991, included NWP 26, which authorized the filling of up to 10 acres of nontidal wetlands. In 1996 the threshold for use of NWP 26 was reduced to 3 acres (Fed. Regist. 61(Dec. 13):65874 –65922). More recently, the Corps eliminated NWP 26 and replaced it with NWPs for which the impact threshold does not generally exceed 0.5 acres of discharge into nontidal waters.

As noted earlier, NWPs may authorize activities to occur in wetlands with little agency oversight. Indeed, some activities authorized by general permit allow the permittee to proceed without notifying the Corps. These are commonly referred to as “nonreporting” NWPs and include activities for which the notification impact thresholds are not exceeded. If a project's impacts fall below the notification impact threshold, the project is automatically authorized and the Corps does not require that the applicant provide written documentation. No mitigation is required for impacts authorized by nonreporting NWPs. Nonreporting NWPs make it difficult for the Corps to determine overall program impacts.

Many NWPs now require a prospective permittee to provide the Corps with a preconstruction notification (PCN). For NWPs that trigger a PCN, the Corps may now require compensatory mitigation (Fed. Regist. 65(Mar. 9):47). Table 4–1 lists current NWPs and notes whether they are nonreporting NWPs or ones that require a PCN.

TABLE 4–1 Listing of Current Nationwide Permits

|

Nationwide Permit |

SEC |

MAX |

PCN |

DEL |

PLAN |

|

1. Aids to navigation |

10 |

||||

|

2. Structures in artificial canals |

10 |

||||

|

3. Maintenance |

10/404 |

C |

|||

|

i. Currently serviceable structure |

10/404 |

||||

|

ii. Sediment and debris removal [all waters] |

10/404 |

200 |

A |

||

|

iii. Upland restoration [all waters] |

10/404 |

A |

|||

|

4. F&W harvesting, enhancement, and attraction devices and activities |

10/404 |

||||

|

5. Scientific measurement devices |

10/404 |

C |

|||

|

6. Survey activities |

10/404 |

||||

|

7. Outfall structures and maintenance |

10/404 |

A |

|||

|

i. Outfall structures |

10/404 |

A |

D |

||

|

ii. Maintenance excavation |

10/404 |

A |

D |

B |

|

|

8. Oil and gas structures |

10 |

||||

|

9. Structures in fleeting and Anchorage areas |

10 |

||||

|

10. Mooring buoys |

10 |

||||

|

11. Temporary recreational structures |

10 |

||||

|

12. Utility line activities |

10/404 |

1/2A (Total) |

C |

D |

|

|

i. Utility lines [all waters] |

10/404 |

C, 500 |

D |

||

|

ii. Substations [nontidal waters only] |

10/404 |

1/2A |

C, 1/10 |

D |

|

|

iii. Foundations [all waters] |

10/404 |

C |

D |

||

|

iv. Access roads [nontidal waters only] |

10/404 |

1/2A |

C, 500 |

D |

|

|

13. Bank stabilization |

10/404 |

C, 500 |

|||

|

14. Linear transportation crossings |

10/404 |

C |

D |

A, C |

|

|

a. (1) Public — [nontidal waters, excluding wetlands adjacent to tidal] |

10/404 |

1/2A |

C, 1/10 |

D |

A, C |

|

a. (2) Public— [tidal waters, including adjacent nontidal wetlands] |

10/404 |

1/3A, 200 |

C, 1/10 |

D |

A, C |

|

a. (3) Private— [all waters] |

10/404 |

1/3A, 200 |

C, 1/10 |

D |

A, C |

|

15. U.S. Coast Guard-approved bridges |

404 |

||||

|

16. Return water from upland contained disposal areas |

404 |

||||

|

17. Hydropower projects |

404 |

A |

|||

INSPECTION AND ENFORCEMENT

Once the Corps issues an individual or a general permit and the permittee has commenced construction of the permitted project, the Corps may visit the construction site to determine whether the avoidance and minimization requirements are being followed. If the permit requires that the permittee provide compensatory mitigation, the Corps may require the permittee to provide periodic monitoring of the physical features of the site. If the compensation is made through a permittee-sponsored or commercial mitigation bank or a fee payment program (see more discussion of the difference in Chapter 5), the inspection process focuses on the off-site mitigation area. In these cases, the Corps also may expect that monitoring reports be filed.

Corps headquarters expects that its staff will inspect a relatively high percentage of compensatory mitigation sites to ensure compliance with permit conditions, the banking instrument, or the conditions in the fee agreement. However, to minimize the number of field visits and the associated expenditure of limited staff resources, Corps field offices may ask the responsible mitigation providers to certify that the mitigation is being done in accordance with agreed-to conditions when they submit their monitoring reports (USACE 1999a).

Once the mitigation site matches predetermined criteria that may be included in a permit's performance standards, a banking instrument, or some other form, the Corps will sign off on the mitigation, deeming that the requirements have been satisfied. Many permits allow for this sign-off or regulatory certification after 5 years. Although the Corps may find that a site satisfies the legal requirements of a permit and will therefore provide its regulatory certification, the mitigation site may not achieve the desired functional effectiveness (Josselyn et al. 1990). Once the sign-off has occurred, there typically is no legal requirement on the permittee to maintain the mitigation site.

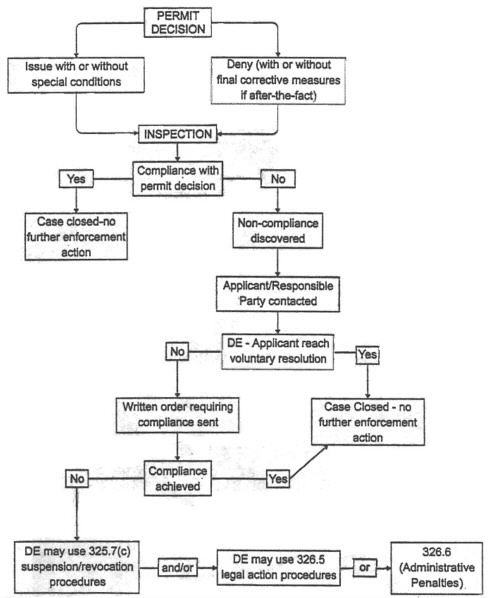

The Corps has primary enforcement jurisdiction over violations of permit conditions, including conditions relating to compensatory mitigation (USACE/EPA 1990). If the Corps discovers a violation of a permit condition, it may issue a compliance order, initiate civil judicial action, and/or suspend or revoke the permit (see Figure 4–4). In some cases, especially with mitigation banks, the party responsible for the compensatory mitigation may be asked to post financial assurances against the possibility that the mitigation will not achieve the required results. The Corps can determine whether these financial assurances will be returned to the responsible party or be used to repair the site. However, as with site inspection, enforcement actions are not a high priority for the use of limited Corps staff time and budget. This problem is discussed later in the report.