7

Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Psychosocial and Physical Symptoms of Cancer

Jimmie C.Holland, M.D.

Lisa Chertkov, M.D.

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

We are not ourselves when nature, being oppressed, commands the mind to suffer with the body.

King Lear, Act II Sc. IV, Li. 116–119

INTRODUCTION

After years of neglect, care at the end of life is receiving increasing attention and concern. We are beginning to recognize that when death is near, the body is suffering the effects of a progressive and mortal illness and that the person is coping not only with the bodily symptoms, but also with the existential crisis of the end of life and approaching death. As the body suffers, the mind is indeed “commanded…to suffer with the body,” as Shakespeare so well described. Thus, the suffering encompasses both the mind and the body. The imperative of providing optimal symptom relief and alleviation of suffering is the highest priority in care. However, evidence suggests that we are failing to do this (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 1998; Carver and Foley 2000; Cassel and Foley, 1999; Cassem 1997). Although pain management guidelines have been the most widely disseminated, we know that many patients continue to suffer not only from pain, but from other troubling symptoms in their final days (Ahmedzai, 1998; American Academy of Neurology, 1996; American Board of Internal Medicine, 1996; American Nursing Association, 1991; American Pain Society, 1995; Carr et al, 1994). Despite clear advances in the identification and

treatment of psychiatric disorders, we continue to underdiagnose and undertreat the debilitating symptoms of depression, anxiety and delirium in the final stages of life (Breitbart et al., 2000; Carroll et al., 1993; Chochinov and Breitbart, 2000; Hirschfeld et al., 1997; Holland, 1997, 1998, 1999). Also, beyond these physical and psychological symptoms, we fall even shorter of our goals of alleviating the spiritual, psychosocial, and existential suffering of the dying patient and family (Cherny et al., 1994, 1996; Fitchett and Handzo, 1998; Karasu, 2000). Yet the ethical and professional challenge to do so is as important as the obligation to cure (Pellegrino, 2000).

In seeking to provide better care for patients at the end of life, the most effective approach appears to be the use of clinical practice guidelines that establish a benchmark of quality based on the delivery of evidence-based medicine (Chassin, 1998; Field and Lohr, 1990, 1992; Field and Cassel, 1997). This chapter outlines the current status of clinical practice guidelines to guide management of psychiatric, psychosocial, and spiritual distress in the context of managing the physical symptoms at the end of life. The focus is on the management of distress and the interaction of physical symptoms and distress.

Clinical Practice Guidelines in Cancer Care

Public and private agencies in the United States have increasingly focused on the quality of health care being delivered (Emanuel, 1996; Ford et al., 1987; IOM, 1999; Patton and Katterhagen, 1997; Stephenson, 1997). This has been particularly useful in cancer because it has encouraged the scrutiny of care delivered across the disease continuum and the establishment of practice guidelines (Morris, 1996).

Clinical practice guidelines are defined as “systematically developed statements to assist both practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” (Field and Lohr, 1990, 1992). Guidelines are based on evidence derived from research or clinical trials, or from a consensus of experts when objective evidence is not available. There are two types of guidelines in use. The algorithm or path guideline, the most widely used, directs decisionmaking toward a set standard. The other type is the boundary guideline that defines the appropriate use of a new technology or intervention (often as a cost-saving device). The National Cancer Policy Board (NCPB) noted in Ensuring Quality Cancer Care that the use of systematically developed clinical practice guidelines, based on best available evidence, improved the quality of care delivered (IOM, 1999). Smith and Hillner (1998) reviewed the status of clinical practice guidelines, critical pathways, and care maps and found that care improved with the use of explicit guidelines in 55 of 59 published studies and in 9 of 11 studies that assessed defined outcomes.

However, a guideline has no impact on health care unless providers endorse and use it. Directly involving physicians in the development of guidelines, holding them accountable through peer pressure, monitoring their compliance, and providing feedback about performance and potential positive effects on outcome are critical to their being used (Katterhagen, 1996). An important corollary, endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), which has developed guidelines for all cancer sites and many symptoms, is the importance of regular review to update and revise guidelines to reflect new information that impacts on practice. Since much depends on the human element of physician “buy-in,” ways to ensure cooperation, dissemination, implementation at the clinical level, and accountability for applying them will continue as important research questions (Grimshaw and Russell, 1993).

Ensuring full application of practice guidelines poses special challenges when applied to end-of-life care. Comfort care is affected by a range of cultural factors: the customs and ethnicity of the patients and their families; community norms and expectations; religious and philosophical belief systems. Physicians’ personal attitudes and beliefs about death also affect their interest and participation in end-of-life care. Development and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines for end-of-life care must take into account the unique aspects of treatment during this period. The task becomes daunting, given the recognized problems with implementation of clinical practice guidelines for pain management and the complexity of developing guidelines that direct both medical and psychological care. The majority of existing clinical practice guidelines in cancer are directed toward the management of specific cancer types and stages of disease. Most have been developed through the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), NCCN (McGivney, 1998), the American College of Surgeons (ACoS), and the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ, formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research) (Table 7-1; Smith and Hillner, 1998). AHRQ also has developed an Internet-based clearinghouse for all practice guidelines meeting certain criteria.

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR END-OF-LIFE CARE

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1996, 1998) defined end-of-life care as “the active, total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment.” The focus at this point is to attain maximal quality of life through control of physical and psychological, social, and spiritual distress of the patient and family. Hospice philosophy has long supported this integrated approach, as well as giving attention to the caregiver. The wide range of these issues makes the task of developing clinical practice guidelines more formidable but, at the same time, more critical. The 1997

TABLE 7-1 Selected, Publicly Available Oncology Guidelines, by Sponsoring Group

|

Group |

Guidelines |

Comment |

|

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

Path or algorithm guidelines for all common cancers |

Evidence based, with consensus; when no consensus possible, options listed Intended for mandatory use for all participating cancer centers No date set for implementation No set benchmarks for care Adopted in the community for use outside of NCCN cancer centers No data yet on compliance or outcomes |

|

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

Boundary guidelines for new technologies Hematopoietic growth factors Outcomes important enough to justify treatment Antiemetics Surveillance of breast and colorectal cancer patients Path or algorithm guidelines for specific diseases Management of non-small cell lung cancer Metastatic prostate cancer |

Evidence based, with consensus demanded before approval Adopted by the community but no data available on compliance or outcomes Likely that all future guidelines will be boundary guidelines for new technologies, with overlap of ASCO and NCCN methods and topics |

|

Society for Surgical Oncology |

Path guidelines for management of common surgical problems |

Consensus panels |

|

American Urology Association |

Path guidelines for common urology problems |

Consensus based on evidence |

|

University of California (UC) Cancer Care Consortium (UC and PONA, Inc.) |

Path guidelines for most solid tumors |

PONA did systematic reviews, consulted with UC faculty for consensus |

|

SOURCE: Smith and Hillner, 1998. |

||

Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Approaching Death stated that ensuring quality of care requires that recommendations be made by experienced professionals; that clear goals of care are established; that patients have access to clinical trials, if desired; that a patient receives the available services in a coordinated manner; that the patient is told and understands the treatment options; that there is available an appropriate range of psychosocial services; that the care be given in a compassionate way; and that the care integrates the physical and psychosocial elements.

The need for guidelines has also been acknowledged by policy analysts, health care professionals, patients, families and third-party payers, and work is progressing toward developing them (see Table 7-2). The ASCO Task Force on Cancer Care at the End of Life set out a basic principle for end-of-life care of “optimizing quality of life…with attention to the myriad physical, spiritual and psychosocial needs of the patient and family” (ASCO, 1998). An NCCN panel has begun adapting general guidelines for nausea and vomiting and for pain control for end-of-life care (Dr. Michael Levy, personal communication). Several large institutions, including Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, have developed guidelines for end-of-life care. Development of algorithm-based clinical practice guidelines relating to psychiatric, psychosocial, and spiritual domains has the potential to enhance end-of-life care in a major way by defining a gold standard for clinicians in an area not previously subjected to this level of scrutiny.

This chapter outlines the status of clinical practice guidelines that relate to end-of-life care and suggests next steps for policy development.

The areas reviewed in this chapter are:

-

communication with patient and family;

-

management of distress (psychiatric, psychological, social, existential, spiritual) in the patient and family; and

-

management of several physical symptoms that are common at the end of life: pain, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dyspnea.

A key concept for end-of-life care guidelines is the recognition that the physical and the psychosocial, existential, and spiritual concerns are interrelated and overlapping, so it is critical that the patient experience appropriate attention to both (Twycross and Lichter, 1998; Wanzer et al., 1989).

Communication with Patient and Family

Central to ensuring quality of all care at the end of life is communication between the doctor, patient, and family (Girgis and Sanson-Fisher, 1995; Ptacek and Eberhardt, 1996). Identification and management of symptoms—physical and psychological—hinge upon this interaction. Buck-

TABLE 7-2 Clinical Practice Guidelines for End-of-Life Care: Status, Source and Further Development Needed

|

Symptom |

Status |

Source |

Further Development |

|

Overall end-of-life care |

NCCN Practice Guidelines (pending) (NCCN, 2001) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Pilot testing; modify for end-of-life care |

|

Doctor-patient communication |

NCCN Practice Guidelines: breaking bad news (pending) (NCCN, 2001) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Pilot testing; modify for end-of-life care |

|

Distress |

NCCN Practice Guidelines: ambulatory care Definition—Psychosocial, existential or spiritual (NCCN, 1999) |

|

Algorithm for recognition and referral; modify for end-of-life care |

|

Delirium |

APA Practice Guidelines: physically healthy (APA, 2000) NCCN Practice Guidelines: ambulatory care (NCCN, 1999) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Modify for medically ill and end-of-life care Modify for end-of life care; pilot test |

|

Depressive disorders |

APA Practice Guidelines: physically healthy (APA, 2000) NCCN Practice Guidelines: ambulatory care (NCCN, 1999) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Modify for end-of-life care Modify for end-of-life care; pilot test |

|

Anxiety disorders |

APA Practice Guidelines: panic disorder in healthy patients (APA, 2000) NCCN Practice Guidelines: ambulatory care (NCCN, 1999) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Modify for medically ill/end-of-life care Modify for end-of-life care; pilot test |

|

Personality disorders |

APA Practice Guidelines (APA, 2000) NCCN Practice Guidelines: ambulatory care (NCCN, 1999) |

Evidence, consensus, or combination Evidence, consensus, or combination |

Modify for medically ill and end-of-life care Modify for end-of-life care; pilot test |

man (1998), an oncologist who teaches communication skills, noted, “Almost invariably, the act of communication is an important part of therapy: occasionally it is the only constituent. It usually requires greater thought and planning than a drug prescription, and unfortunately it is commonly administered in subtherapeutic doses.”

Within the area of communication, teaching how to break bad news has been given the most attention, since it is a common task facing oncologists. An NCCN panel has developed algorithm-based guidelines for delivering bad news, which are being revised for application to end-of-life care (Dr. William Breitbart, personal communication). A review of the literature from 1975 to 1999 (Holland and Almanza, 1999) revealed that of the 166 articles published on this topic, the majority were written in the past five years, reflecting the recent, increased concern about this issue. However, only 14 percent of the studies were based on controlled trials; most papers were based on consensus or clinical experience. Baile and colleagues (1999) proposed guidelines for discussing disease progression and end-of-life care.

Several tenets of importance emerge: finding out what the patient understands; learning how much more or less information does she or he want to know; being sensitive to and empathic with whatever emotions the patient expresses; listening attentively and allowing tears and emotions to be expressed without signs of being rushed; and taking into account the family and its ethnic, cultural and religious roots. All may contribute to decisions about care (Braun et al., 2000; Hastings Center, 1987). These tenets should include attention to the needs of traditionally medically underserved patients: those with little or no English proficiency, for whom care at the end of life is particularly difficult because communication is limited, and patients with chronic mental illness or limited education.

The need for communication guidelines and standards is accentuated because of the awkwardness that many professionals feel in talking with patients about death, as well as the difficulty patients themselves have in expressing their fears and uncertainties about their possible death.

Family members face similar challenges in expressing their feelings and asking questions about prognosis. A series of 19 focus groups held in eight cancer centers comprised either doctors alone, nurses alone, or patients alone. The doctors felt they had more trouble communicating with families than with the patients themselves (Speice et al., 2000). Patients noted that their relatives often felt “left out” and “in the way.” These issues are particularly disturbing since impending death has a profound impact on the family who shares the death vigil with the doctor. Family members often recall in exquisite detail the sensitivity (or lack of it) of the doctor and staff as their relative was dying. These memories affect the grieving process, recalling as they do the details of how the family was told by the doctor about what was being done, how it was informed of changes in the medical

situation, and especially how attentive the doctor and the staff were in controlling the patient’s distress and physical symptoms (Chochinov et al., 1998; Zisook, 2000).

Communication with Patient and Family: Next Steps

-

Training of doctors in communication skills is critical to ensure quality end-of-life care. The best teaching model is one that uses faculty from the physician’s own discipline (e.g., oncologists for oncologists) as well as a physician or mental health clinician skilled in teaching communication. Such workshops have proven to have a low priority for voluntary attendance; mandating participation via required risk management lectures is useful. The content of the skills teaching sessions is best acquired when the groups are small in number, when they use videotapes of model patterns of communication, and when they include role playing, which enhances sensitivity to patients’ emotional responses and also to the doctor’s own responses.

-

Research is needed to determine the best teaching methods. Approaches based on a theoretical model of stress are effective, such as the Transpersonal Model of Stress, which examines physicians’ and patients’ responses at each phase of the discussion (Ptacek and Eberhardt, 1996).

-

Improving communication with family is recommended, especially in view of the role families now play in physical care at the end of life and the intense psychological impact of this time in their lives and for years to come. We have to explore ways to educate the family in how to manage pain, distress, and other symptoms in the patient and how to communicate with the doctor about their concerns.

Management of Distress in End-of-life Care

A diagnosis of incurable cancer carries with it a necessity for patient and family to look at the meaning they attach to life and death. For many in America, this may be the first unavoidable confrontation with death because, as a society, we prefer to avoid thoughts of death—the last taboo topic. A 1991 Gallup poll found that most people in the United States reported that they never, or almost never, thought about death (Gallup and Newport, 1991). Callahan (1993) observed that much of the public excitement, debate, and furor about physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia is really an attempt to “control death” and thereby avoid facing the actual meaning of death in personal terms.

Given this cultural environment in which the meaning of death is denied and the fact that, in recent decades, oncology research has focused primarily on finding cures as opposed to improving palliative care, it is no

surprise that the “human” side of end-of-life care, dealing with the emotional distress of being forced to consider the meaning of death, has received less attention. To meet patients’ needs for psychological, social, and existential-religious-spiritual concerns, the primary treatment team should include (or have available to it) a psychosocial team that consists of a social worker, a mental health professional, and a pastoral counselor. Currently, the social worker often performs as the entire psychosocial team, but although long distanced from the treatment team, pastoral counselors must come to be viewed as integral members.

Mental health professionals can play an important role in helping dying patients deal with their distress. However, negative attitudes and stigma related to mental health, especially psychiatry, often limit the availability of these services. Medical staff are reluctant to ask for a psychiatric consultation, even when it is highly appropriate, out of concern that a patient may be offended by the request to see a mental health professional. Sometimes, the family sees it as an affront to the patient at a time of grave illness. These barriers, similar to those in pain management, are compounded by other fears. Patients and families often fear psychotropic medication. They worry that the drugs used will be addictive and “make me a zombie.” Their attitudes are expressed by comments such as “I have to be strong” and “what can be done to change things?”

Another barrier is perceived cost. Many institutions regard this human aspect of care as expendable, expensive, and unnecessary. As a consequence, too few social workers, mental health professionals, and pastoral counselors are available to provide the consultation and treatment that would benefit patients and their families when the severity of distress exceeds that readily managed by the primary team. This is especially true of bereavement services, as social workers are reduced as a cost-saving measure.

A major problem in palliative care is the underrecognition, underdiagnosis, and thus undertreatment of patients with significant distress, ranging from existential anguish to anxiety and depression. This situation continues to exist despite the fact that when dying patients themselves were asked their primary concerns about their care, three of their five concerns were psychosocial: (1) no prolongation of dying; (2) maintaining a sense of control; and (3) relieving burdens (conflicts) and strengthening ties (Singer et al., 1999).

Even though patients and families express clearly their wishes for attention to their nonmedical concerns and for the inclusion of this domain as a core element in palliative care, there remains significant evidence that inadequate attention is given to these issues, in spite of lip service and good intentions. The evidence is as follows:

-

There are no standards of care for psychological, social, and existential and spiritual care at the end of life.

-

No training standards exist to formally prepare physicians to identify patients with distress, nor are there standards of competence for those who provide psychosocial and spiritual services at the end of life.

-

Mental health professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric social workers, and nurses) and pastoral counselors are not included in the end-of-life care team.

-

There is, as yet, no accountability for the performance of physicians, staff, and institutions in relation to the psychosocial and spiritual care given at the end of life by any regulatory body.

-

Reimbursement of professional services for psychosocial care is poor to absent (often excluded from medical and behavioral health contracts).

Clinical practice guidelines and standards for the management of distress in end-of-life care must incorporate the psychological, social, existential, spiritual, and religious issues faced by patients—the “human” aspects of care. However, the distress relates to coping with the increasing physical symptoms that, by their own nature, become a major source of distress. Patients and families often say that their greatest fear is having pain that cannot be controlled. Cherny and colleagues (1996) used the word “suffering” to encompass these same issues. They included physical symptoms based on the commonly used term “pain and suffering.”

The word “distress” is chosen because it is less stigmatizing and incorporates “normal emotions” such as worry, fear, and sadness. However, distress can increase along a continuum to become a full-blown psychiatric disorder such as a major depression or generalized anxiety. Sadness of separation and anticipatory grief may increase to severe distress in the family. The normal search for meaning may increase to become an existential crisis with spiritual or religious meanings and require the advice of a pastoral counselor (Rousseau, 2000). This concept has been the basis for the NCCN guidelines and standards for the management of distress (Holland, 1999).

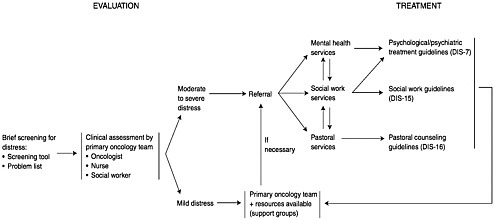

The NCCN practice guidelines (Table 7-2; Figure 7-1) give an algorithm for rapid identification of patients with significant distress leading to referral to appropriate services when significant distress is found. They also provide the first practice guidelines for mental health, social work, and pastoral counselors.

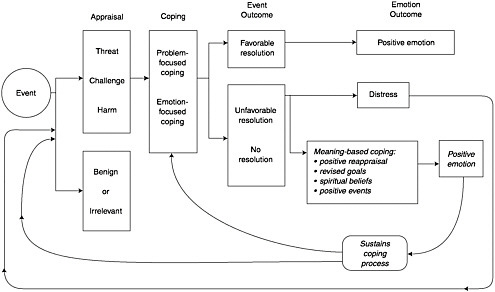

Distress is a word that also describes the emotions that reflect an inability to cope with the threat to life and the search for ways to give it tolerable meaning. The model of Folkman (Figure 7-2) is useful because it provides a cognitive model of the universal process by which we cope with an overwhelming situation and the distress that it causes (Folkman, 1997). The

model demonstrates how the psychological, social, spiritual, existential and religious are joined in the effort to reduce distress by finding a tolerable meaning in the existential crisis. The effort is to reconcile the meaning of this unresolvable threat to life with the global meaning—the long held values, beliefs, aspirations, and goals that were held prior to the illness. The person seeks a resolution of these two conflicting forces and may cope in several ways: (1) by utilizing positive reappraisal such as viewing death in another way (e.g., “I’ll pass on to an afterlife”); (2) by revising or coming to terms with shortened goals (e.g., “I will not see my children marry”); (3) by using spiritual beliefs (e.g., “God—ultimately—will make all things well”); and (4) by finding positive events in the situation (e.g., “I have had some wonderful moments with my children that I never had before”). The particular value of the Folkman model is its demonstration of how the psychosocial and the spiritual or religious domains are integrated in the patient’s coping which, when successful, reduces distress.

Development of Standards for Management of Distress

In an effort to improve recognition and treatment of distress, the successful guidelines for pain management have become the model for guidelines to manage distress. The NCCN convened a multidisciplinary panel in 1998 to address the status of psychosocial care in cancer and the need for clinical practice guidelines to guide clinicians. The panel, over two years’ time, developed standards of care and an algorithm that triggers referral of a significant level of distress to mental health, social work, or clergy services (Holland, 1999). It also developed clinical practice guidelines for these supportive care disciplines to guide their management of cases. These constitute the first set of clinical practice guidelines for psychosocial and spiritual care developed with full participation of all the supportive care disciplines (psychiatry, psychology, chaplaincy, social work, nursing), as well as oncology and patient advocacy. The principles laid out by this NCCN panel serve as the basis for the end-of-life guidelines outlined below.

-

Standard 1. The term distress is used as a global term to refer to psychosocial or spiritual issues (Holland, 1999). As a nonstigmatizing word, patients can respond without embarrassment. Distress is defined as “an unpleasant experience of an emotional, psychological, social, or spiritual nature that interferes with the ability to cope with cancer treatment. It extends along a continuum, from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fear, to problems that are disabling, such as true depression, anxiety, panic, and feeling isolated or in a spiritual crisis.”

-

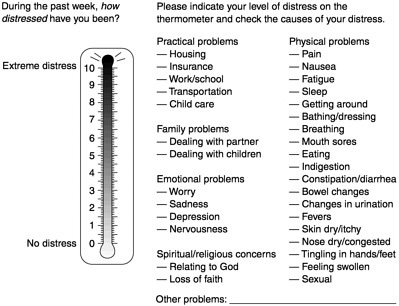

Standard 2. The level of distress should be assessed at each visit, whether this occurs at home, in the clinic or office, or at the hospital or

-

hospice. A rapid visual analog approach is used by a verbal question, How is your distress today on a scale of 0–10? or by making a hatch mark on the distress thermometer (Figure 7-3). The thermometer is accompanied by a problem list on which the patient marks the nature and source of the distress (physical, social, psychological, or spiritual). The list of physical symptoms assists in targeting patients’ major concerns. Patients have found this acceptable, and physicians have found that it serves as a checklist that allows questions to be more directed. Several screening methods are available (Hopwood et al., 1991; Ibbotson et al., 1994; Razavi, 1990).

-

Standard 3. When a patient indicates a distress level of 5 or above, this is the algorithm that triggers referral to one of the specialized supportive services, depending on the problem: mental health, social work, or pastoral counseling. Roth and colleagues (1998) found the level of 5 or above comparable to a significant distress level on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Further studies of feasibility and validity are under way with sponsorship from the American Cancer Society.

-

Standard 4. Standards for professional education and training in end-of-life care must include standards for physicians and nurses, as well as

FIGURE 7-3 The distress thermometer.

-

for social workers, mental health professionals (psychiatry, psychology), and pastoral counselors.

-

Standard 5. Physicians and nurses must be trained to use rapid screening methods to ensure that patients are asked at each visit about their level of distress and must be able to use the algorithm to refer patients to community resources for psychosocial services. Ready access to community resources is important (e.g., a phone referral list). They must be trained in how to communicate with patients and families in an empathic, compassionate, and supportive manner (Fallowfield et al., 1998; Holland and Almanza, 1999; Maguire, 2000; Maguire and Faulkner, 1988).

-

Standard 6. Patients and their families, as well as all professionals engaged in end-of-life care, must be educated about the fact that psychosocial and spiritual services are an integral part of total care. Patients should experience no discontinuity between their medical and supportive services.

-

Standard 7. Appropriate reimbursement for psychosocial services must be considered in all policy planning for end-of-life care.

-

Standard 8. Evaluation of the quality of end-of-life care must include attention to the management of distress (Kornblith and Holland, 1996).

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Mental Health, Social Work, and Pastoral Services

The multidisciplinary NCCN panel addressed the need for an integration of psychosocial supportive services and the need for practice guidelines for the professionals who provide these services. While the primary care team manages normal levels of distress, higher, more severe levels, presenting as frank psychiatric symptoms or disorders, require management by a mental health professional (e.g., psychiatry, psychology, social work, nursing). Many oncology social workers on the primary treatment team also serve as the mental health professional. A psychiatrist should evaluate a neuropsychiatric disorder or one requiring psychotropic drug management. Significant psychosocial or concrete problems (e.g., transportation, insurance) are referred for social work services (Loscalzo and BrintzenhofeSzoc, 1998). Patients who are experiencing a spiritual or religious crisis are referred to the pastoral counselor or chaplain.

The family and other caregivers are the “secondary patients” since they are experiencing distress along with the patient: worry, sadness, uncertainty, and fatigue of caregiving while maintaining work and home. Managed care has placed an even greater burden on families as hospital length of stay is shortened, more treatments are provided on an outpatient basis, and home care services are reduced. They are a crucial “invisible” piece of the health care continuum. Anticipatory grief is part of their daily distress. Fears of How will he die? and Can I manage? add to the stressors. Studies

suggest that while family caregivers persist in their caregiving role, they are subject to increased illness and mortality.

The same guidelines apply to recognition of distress in the family, and the same obligation exists to recognize and treat it, including management of bereavement after the death of the loved one when the staff who knew the patient will have a relationship and can monitor the need for intervention.

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Common Psychiatric Disorders

Several common psychiatric symptoms or disorders (using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV]) are encountered during end-of-life care (Table 7-2). Psychiatrists and psychologists with expertise in problems occurring at this stage can substantially diminish the distress of patients and their relatives. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Clinical Practice Guidelines are useful for modification for end-of-life care, as are the NCCN guidelines for the management of these disorders specifically in cancer patients (APA, 2000; Holland, 1997; Holland and Almanza, 1999).

Delirium

Delirium is a common psychiatric disorder toward the end of life, estimated to affect as many as 85 percent of patients in their final days (Massie and Holland, 1983). The etiology of delirium in the terminally ill cancer patient is often multifactorial including medication side effects, infection, organ failure, metabolic derangement, and direct central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Older individuals who have mild impairment of cognition are especially susceptible to delirium. In the final stages of life, it is unlikely that the cause of the delirium can be resolved, and attention should focus on comfort. All too often, “quiet delirium” is ignored, but patients may be distressed by delusions that frighten them. Patients’ capacity to make health care decisions must be assessed at times and the health care proxy identified. Considerable research has gone into management of delirium by pharmacologic means (see Table 7-2) (Kress et al., 2000).

Delirium is sometimes accompanied by agitation with self-injurious behavior (e.g., pulling out intravenous lines) or less frequently, the risk of injuring others (Johanson, 1993). Sometimes, poor impulse control, confusion, and depression combine to result in poorly planned, impulsive suicide attempts. Loved ones are frightened by a sudden change in behavior, and they need explanation as to the origin—be it related to disease or medication effects or both. Patients also need explanation since they fear, “I’m losing my mind” (Chochinov and Breitbart, 2000).

Thus, appropriate intervention in delirium includes steps to ensure early identification, safety of the patient, interventions (to treat both the delirium and its underlying cause, if possible), and education of patient and family to decrease distress associated with this disturbing symptom (see Table 7-2).

Depression and Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms are common at the end of life, often at the subsyndromal level or as part of an adjustment disorder (Wilson et al., 2000) (Table 7-2). The etiology must first be determined, ruling out metabolic, illness-, or drug-related causes. Irrespective of the etiology, attention is directed to the treatment of the depressive symptoms. A prior history of bipolar disorder or dysthymia suggests a longstanding problem that may be exacerbated during end-of-life care. Evaluation of suicidal ideation and risk is essential, as well as of the capacity to make decisions. The role of depression in requests for physician-assisted suicide makes this a critically important aspect of evaluation and treatment (Burt, 1997). The presence of hopelessness appears to be a separate but related factor, along with depression, in suicidal wishes (Breitbart et al., 2000). The notion that depression is an ordinary aspect of the end of life has been dispelled by careful longitudinal studies by Chochinov and colleagues, who found a high level of fluctuation in suicidal wishes day-to-day, suggesting caution in acting on a patient’s stated wish at a particular time (Chochinov and Breitbart, 2000; Passik et al., 1998, 2000; Razavi et al., 1990).

Meeting criteria for true major depression (DSM-IV criteria) is not common, but when major depression is present, it should be treated as aggressively as any physical symptom, with psychological support, psychotherapy, and medication. Antidepressants and psychostimulants are of proven value. Existential forms of psychotherapy are under development by the authors and colleagues. Guidelines for treating end-of-life depression are still needed. A start could be made by modifying more general depression treatment guidelines (see Table 7-2). Education for clinical staff about depression, anticipatory grieving, and bereavement is essential for appropriate implementation of guidelines.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is the most common symptom of distress near the end of life. It often stems from fears about shortness of breath, fear of pain, unremitting symptoms, and uncertainty about the future. Reactive anxiety symptoms alone, or mixed with depressive symptoms, constitute the mildest DSM-IV psychiatric disorder, adjustment disorder (APA, 2000). The patient requires

careful evaluation for illness or medication-related causes: neuroleptic-induced akathisia, corticosteroids, hypoxia or hypercarbia, glucose imbalance, bronchodilators, drug intoxication or withdrawal, and metabolic changes. All must be considered when failure of vital organs is occurring. Explanation of symptoms and preparation of the patient and family for approaching death are important. Communication about fears plays an essential role in modulating patient and family anxiety and distress. Assessment of patients’ safety and supportive psychotherapy, with or without an anxiolytic or antidepressant medication, is indicated.

Generalized anxiety disorder with distressing phobias and panic symptoms, usually antedating the illness, requires titrating medication to control symptoms, along with giving psychological support. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may be present at the end of life in patients who have undergone extensive, aggressive treatment with prolonged, poorly controlled pain. Supportive psychotherapy is indicated for these patients along with medication to treat anxiety and sleep problems.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a type of anxiety disorder that complicates end-of-life care. These patients are often fearful of accepting psychotropic and usually pain medications, have trouble making decisions about treatment and care, and as a result, often suffer more because of inadequate treatment of their symptoms. Family support of decisions and psychotherapy from a mental health professional are of value. End-of-life anxiety guidelines are needed and could be developed by modifying more general anxiety guidelines (see Table 7-2).

Personality Disorders

Patients nearing the end of life may have difficulty in controlling emotions, and underlying personality problems may emerge that require evaluation and intervention. Patients may become angry and hostile, uncooperative and demanding, overly fearful and dependent, indecisive and ambivalent about care, or manipulative and creating conflicts among team members. Such symptoms are best evaluated and recommendations made by a mental health team member. In addition to intervening directly with the patient, a mental health professional can assist staff in managing clinical problems— negotiating behavioral changes, maintaining appropriate boundaries, and addressing conflicts among staff members that arise around caring for such challenging patients. Both the APA Clinical Practice Guidelines for management of personality disorders in physically healthy individuals and the NCCN guidelines for management of distress in ambulatory cancer patients should be revised to provide guidelines for their management in palliative care (see Table 7-2).

Social Work Services Guidelines

The NCCN practice guidelines, developed by social workers and a multidisciplinary panel, determined that the services given by social workers fall into two domains: psychosocial services and concrete services such as transportation. They constitute the first algorithm-based treatment guidelines for delivery of social work services in cancer. These guidelines require only minor revision to apply to end-of-life care. The role of social workers varies enormously across institutions; in some, they provide all of psychosocial services as they address all the psychosocial needs of both patients and families during palliative treatment (see Table 7-2).

Pastoral Services Guidelines

Long an integral part of hospice care, interest is growing in how we can better incorporate the spiritual and religious domains in palliative care in all settings (Post et al., 2000). When life ebbs, beliefs and philosophy take on new meaning so that the clinician should be sensitive to the need to explore these areas with a patient and, if the patient expresses concerns about spiritual or religious matters, to refer him or her to a pastoral counselor (Puchalski and Romer, 2000). The NCCN practice guidelines for management of distress include pastoral counseling as part of psychosocial services to encourage the integration of pastoral services into total support services (Holland, 1999). The common problems referred to pastoral counselors, and for which they counsel, are grief, concerns about death or afterlife, conflicted belief systems, loss of faith, concerns about the meaning or purpose of life, relationship to God, isolation from religious community, guilt, hopelessness, conflicts between religious beliefs and recommended treatment, and ritual needs (Speck, 1998). Clergy who have been trained in pastoral counseling should be available to assist in end-of-life care. Problems such as guilt, hopelessness, and grief may require mental health or social work evaluation, prompting the need for close collaboration among all staff taking care of patients in a palliative setting (see Table 7-2).

IMPROVING MANAGEMENT OF DISTRESS: FUTURE DIRECTIONS

TRAINING OF TEAM The team giving end-of-life care must be trained in how to recognize, diagnose, and treat distress and in using an algorithm for referrals to mental health, special social work services, or pastoral counseling. A brief curriculum is needed that can be given to staff easily, similar to the curricula in palliative care.

EDUCATION OF PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Patients and their families should be educated to expect attention to and treatment of their distress by their primary care team or by an appropriate resource that is viewed by the patient as an extension of the team. They should experience a seamless flow of medical and mental health services. As nearly as possible, psychosocial and psychiatric services should be given in the same site as medical care to reduce embarrassment and ensure easy access to care for seriously medically ill patients and their families.

PATIENTS’ BILL OF RIGHTS This document should explicitly include the patient’s right to management of distress as an integral part of comprehensive cancer care.

ACCOUNTABILITY Regulatory bodies (e.g., Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Health Care Financing Administration) must include in their reports for medical centers the quality of doctor-patient communication and their ability to recognize and treat distress and to refer to the appropriate psychosocial resource.

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS FOR MENTAL HEALTH AND PASTORAL SERVICES It is essential to have standards for training mental health professionals and pastoral counselors in palliative and end-of-life care, as has been done for physicians and nurses. This is particularly true of pastoral services where cost cutting may lead to use of clergy untrained in counseling techniques. The National Association of Professional Chaplains has developed the requisite standards.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY TEAM The team giving end-of-life care must include a mental health professional and a qualified pastoral counselor either on the team, or available to the team for consultation, as well as a psychiatrist for evaluation and management of neuropsychiatric disorders and depression when patients express the desire for hastened death.

REIMBURSEMENT FOR PSYCHOSOCIAL SERVICES Reimbursement for psychosocial services given at the end of life has to be addressed at a public policy level with attention to the inequity in payment for these services compared to medical services.

RESEARCH Clinical practice guidelines and critical care pathways have proven effective in improving quality of care through the use of evidence-based guidelines. There is a great need to apply this approach to managing the problems of distress so that a gold standard will exist for the psychosocial as well as the physical domains.

Studies are needed to provide more evidence-based (as opposed to consensus) guidelines for recognition and management of distress. Empirical studies should explore the best psychotherapeutic approaches; the efficacy of psychopharmacologic interventions through clinical trials (use of neuroleptics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and psychostimulants in end-of-life care); studies of depression, its predictors, and those associated with requests for physician-assisted suicide; and development of special algorithms for medically underserved populations (e.g., non-English speaking, low income, minorities, chronically mentally ill), with attention to quality-of-life assessment that permits examining patients’ quality of life and satisfaction with care. In addition, family members who care for their loved ones during the end of life should be studied to better understand anticipatory grief, distress, the burden of caregiving, and the management of bereavement.

Implementing Needed Changes

-

A multidisciplinary consensus panel (including all disciplines that provide supportive services) should be impaneled to develop an overall taxonomy for the nonphysical domains of patients at the end of life (i.e., the psychological, social, spiritual, existential, religious, and psychiatric dimensions). This area currently suffers from the use of vague, overlapping terms that lack clarity and definition, and is likely to be relegated to a nonsignificant status. The encompassing term “distress” is proposed to incorporate all psychosocial facets to diminish this fragmentation. A consensus panel of experts is needed to promulgate a standard taxonomy (Holland, 1999).

-

The panel should take existing standards of care and clinical practice guidelines developed by NCCN for use with ambulatory cancer patients and modify them for use at end of life. These should be disseminated and tested for feasibility. Given the problems with ensuring implementation of clinical practice guidelines, substantial efforts must be invested in identifying and overcoming barriers to their widespread use.

-

The panel should also examine the NCCN panel’s work on guidelines for communication and adapt them to end-of-life care. A current NCCN panel has such work in progress (W.Breitbart, personal communication).

-

The panel should address the major barriers to management of distress as discussed earlier:

-

the absence of minimum standards for psychological and social care and for existential, spiritual, and religious needs;

-

the absence of oversight by regulatory bodies regarding the perfor-

-

-

mance of staff in relation to communication, identification, and management of psychosocial and spiritual problems;

-

the negative attitudes of professionals that often demean and discourage integration of these aspects into total care because of the stigmatization of nonphysical “psychological” domains (an equally important barrier is the negative attitudes of patients and families who sometimes feel embarrassed or angered by a consultation by a mental health person, especially a psychiatrist);

-

the absence of training of professional staff in the recognition, diagnosis, and management of distress and the absence of an algorithm to trigger referral to supportive services;

-

the need for mental health professionals and pastoral counselors to be part of, or be an immediately available resource to, the end-of-life care team to address the psychosocial, spiritual, and religious issues; and

-

the absence of reimbursement for these supportive services given to the poor.

-

The panel should outline standards for psychosocial care and obtain endorsement from professional organizations involved in end-of-life care. These should be promulgated in a manner similar to that used with pain management:

-

Distress should be assessed at every visit on a 0–10 scale, verbally or with paper and pencil, identifying the level and source of the distress; using the algorithm of scoring 5 or above, patients should be referred to the proper supportive service that can be accessed in a seamless delivery system from the patients’ perspective.

-

Educational standards must include training of the primary end-of-life care team in the recognition of distress and its management.

-

Educational standards must teach mental health professionals how to modify their concepts to include end-of-life care (psychologists, psychiatrists, psychiatric social workers, and nurses) and clergy who are qualified as pastoral counselors).

-

Pastoral counseling should be included in psychosocial services, since this should not be fragmented and distanced from other aspects of care during end of life.

-

Patients and families must be educated to understand that the psychosocial and spiritual domains are an integral part of their end-of-life care and should not be viewed as disconnected and unrelated.

-

Governmental and managed care organizations must be made aware of the inequity in reimbursement for the nonphysical aspects of end-of-life care which impacts negatively on ensuring quality of care to reduce suffering and distress.

-

-

Professional organizations representing psychology, psychiatry, oncology social work, oncology nursing, and chaplaincy must become familiar with and endorse the clinical practice guidelines modified from existing ones for end-of-life care, to ensure dissemination and education among these disciplines.

-

Any patients’ bill of rights must include the right to management of their distress as a symptom of equal concern as a physical symptom that receives prompt and competent care; they must be educated to ask for these services.

-

Accountability: the appropriate regulatory bodies must include performance standards for professionals in relation to their communication and sensitivity to care of the nonphysical symptoms (psychosocial and spiritual) of patients at the end of life.

-

Research should be pursued to test the feasibility and implementation of practice guidelines for management of distress developed for each discipline (mental health, social work, pastoral counseling) giving supportive services. In view of the acknowledged difficulties in implementation of clinical practice guidelines to manage distress and the unique stigma around psychosocial and spiritual services, it is essential that research be undertaken to address these barriers.

-

Delirium, depression, and anxiety are extremely common at the end of life and are frequently underrecognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated, leading to unnecessary distress for patients and families. Research into recognition and treatment of these symptoms through controlled trials is important to improve care at the end of life.

-

Clinicians are equally responsible for the recognition and treatment of distress in patients’ families who bear an increasingly heavy burden of caregiving with its own psychological and physical toll; guidelines for inquiring about distress and educating families must be a part of the research agenda in end-of-life care.

Management of Physical Symptoms

Table 7-2 outlines the status of clinical practice guidelines for management of pain, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and dyspnea. The focus here is on the emotional distress caused by these symptoms—the physical suffering that we associate with the dying process (Twycross and Lichter, 1998). Patients and families struggle with the concern that these symptoms will not be adequately controlled, with fears about their cause and the potential for their becoming intolerable, and with sadness and anger about diminishing physical function. Thus, the common symptoms of pain, fatigue, nausea, and dyspnea are often the catalyst for severe distress or “suffering of the mind.” They lead to severe distress requiring both traditional medical inter-

ventions and care targeting the spiritual, existential, psychiatric, and psychosocial distress they precipitate.

Negotiating management of physical symptoms at the end of life is often complex: the first issue is dealing with the meaning of the transition from curative to palliative care. This requires sensitive communication by the physician with opportunity for participation of supportive disciplines that can more fully address the concerns of patients and families.

In addition, medical management for the dying patient is complicated by the interaction of the symptoms of disease and the fact that treatments may produce relief or introduce new problems; for example, analgesics cause troubling constipation. Patient education is an essential component of care to ensure a collaborative approach to symptom management. Clinical practice guidelines usually consider a single symptom in isolation; thus, a guideline addressing a single symptom may apply less well because it fails to take into account many coexisting symptoms. Care of the dying requires creative problem solving, as well as the development of clinical guidelines to address this level of complexity. Palliative treatment should be just as aggressively approached as curative treatment. Many patients’ greatest fear is of abandonment, of hearing the echoing words of a physician telling them that there is nothing more that can be done. In fact, treatment of the dying patient continues to the moment of death and beyond, by interventions to assist family members with their grief.

One imperative is improved doctor-patient-family communication about symptoms and more collaborative efforts at symptom management. Uncertainty about the cause of symptoms or what they may signify, fear of future symptoms and worry that symptom control will be inadequate contribute substantially to patients’ and families’ distress. Many fear unbearable and poorly treated pain and respiratory distress in the final days and hours. Clinicians could be helpful by describing the dying process to patients and families in terms of reassurances about comfort and relief of symptoms. Loved ones usually view Cheyne-Stokes respirations as indicators of substantial discomfort and pain or fear that a gurgling sound indicates the patient is drowning, despite the fact that most patients are no longer conscious in this final stage of dying. Adequate preparation of patient and family about the dying process and anticipated symptoms is essential and must begin with showing a willingness to discuss these matters and address fears and concerns. Treatment of distress caused by fear of potentially uncontrolled physical symptoms will significantly improve quality of life. The public issue that has arisen regarding requests for physician-assisted suicide is prompted considerably by the widespread fear of overwhelming pain and its inadequate control in the care of dying patients (Chochinov and Breitbart, 2000; Sachs et al., 1995).

In addition, psychological, social, and existential or spiritual distress

may increase the intensity of physical symptoms. For example, depression and anxiety may increase the experience of pain, and anxiety can increase dyspnea. Conversely, pain and dyspnea increase anxiety and depression.

Prevalence of symptoms at the end of life that cause substantial distress has been identified by the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (Portenoy, 2000). Pain, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and dyspnea are among the most frequently occurring symptoms that reduce quality of life. Others are cachexia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, sleep disturbance, pruritis, constipation, diarrhea, and pressure ulcers (Mercandante, 1994, 1997; Ripamonti, 1994). Anorexia is exceedingly common and emotionally laden, causing patients and families great distress because of the fear that not eating is the cause of cachexia. Patients in the final days of life have diminished hunger and thirst, and oral, parenteral, and enteral force feeding may actually increase suffering (McCann et al., 1994). Development of clinical guidelines for each of these symptoms in end-of-life care is important. Practice guidelines are being developed for anorexia (D.Cella, personal communication).

Symptom management in special populations is a particular problem. In patients with dementia, chronic mental illness, delirium, or deficits in ability to communicate, assessment of the sources of discomfort and the adequacy of palliative interventions is especially problematic. In these cases, clinical experience with comparable situations often must guide palliative care; for example, dosing pain medications based on average needs and then assessing nonverbal cues are recommended. Given the high incidence of terminal delirium and the frequent progressive impairment of cognitive functioning in the final stages of life, palliative care guidelines must address the needs of those patients who cannot speak for themselves to express troubling symptoms.

Pain

Achieving effective pain management has been a priority over the past decade. The American Pain Society (APS), AHRQ, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the NCCN guidelines provide algorithms for decisionmaking in pain management (AHCPR, 1993; APS, 1995; McGivney, 1998; WHO, 1998) (see Table 7-2). Problems remain in implementation; many patients cope with needless suffering. Pain is one of the most prevalent symptoms across terminal illnesses, affecting more than a third of patients. It is also the source of great fear as many patients anticipate final days of agony. Beyond the devastating experience of the symptom itself, pain impairs psychosocial functioning, causes enormous psychological distress (anxiety and depression), and limits patients’ capacity for enjoyment and finding meaning in their final days. Studies show pain control remains a

challenge for research, with modification of existing guidelines for end-of-life care and accountability to regulatory bodies to ensure compliance.

APS, NCCN, and AHRQ guidelines clearly delineate the principles of effective pain management, providing algorithms for the management of nociceptive and neuropathic pain of varying severity and chronicity (Rischer and Childress, 1996) (see Table 7-2). Identification of the cause and type of pain, use of repeated standardized assessment tools to assess pain severity and response to treatment, evaluation of the effect of pain interventions on mental alertness, and flexibility in revising treatment regimens are the mainstays of effective care. The use of around-the-clock fixed dosing with patient or caregiver “rescues” provides a means of avoiding withdrawal symptoms and preventing delays in dosing and resulting pain crises (Bottomly and Hanks, 1990). Clinician education about appropriate dosing and medication combinations facilitates better care as well as treatment of depression and anxiety. Use of psychotropic drugs as adjuncts to pain medications and behavioral interventions are effective.

Continuing misconceptions about dependence and addiction, the risks of oversedation, and regulatory problems of opiates have contributed to inadequate implementation of clinical guidelines. In addition, there is a need to educate doctors about the use of opiates and other medications whose use is restricted by Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) guidelines, in order to resolve the problems of inadequate dosing and reluctance to prescribe. Identifying the barriers that have delayed implementation of effective pain management is a continuing research question.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a major end-of-life symptom described as tiredness, heaviness, weakness, lack of energy, poor stamina, sleepiness, and poor strength. In the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT), 80 percent of patients complained of fatigue in the final three days of life (Phillips et al., 2000). Whether a result of the primary disease process, metabolic abnormalities due to organ failure, treatment side effects, or malnutrition, fatigue limits functional capacity and quality of life. Treatment guidelines have been developed for the management of anemia-related fatigue, but none have addressed fatigue at the end of life. The fatigue related to depression also must be considered in seeking an etiology and choosing an intervention. Despite all efforts, fatigue is often an intractable symptom in the final days of life.

Clinical practice guidelines for this important symptom must build on recent studies documenting the high incidence of fatigue in chronic and terminal illness and its impact on quality of life. Research in the use of stimulants and other new alternatives may offer the potential for future

advances (Chochinov and Breitbart, 2000). The complex interplay of psychological and physical complaints is especially significant in the evaluation and treatment of fatigue.

Nausea and Vomiting

Clinical practice guidelines for management of nausea and vomiting have been widely promulgated in the care of cancer patients as advances in antiemetic therapy have vastly reduced the distress associated with chemotherapy. Nausea may be centrally mediated or caused by local factors such as decreased motility, medication effects, or gastrointestinal lesions (Reuben and Mor, 1986). Vomiting may contribute to dehydration, metabolic disarray, and aspiration. Obstruction and gastrointestinal bleeding are particularly difficult to manage and may be the source of great physical and emotional distress. There are practice guidelines for intractable vomiting, including surgery, PEG drainage, restricted oral intake, and symptomatic medications. Patients have described nausea as a particularly demoralizing symptom, affecting self-concept and self-esteem as well as psychosocial functioning. Inability to eat excludes patients from one of the primary sources of social interaction, occurring at meals. Nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are substantial sources of distress for patients and families, often leading to anxiety and depression.

Development of clinical practice guidelines for nausea and vomiting, central in end-of-life care, requires piloting antiemetic regimens that have been successful in the management of chemotherapy-related side effects. Modification to the special needs of patients in the end of life is the next step (see Table 7-2).

Dyspnea

Respiratory distress and shortness of breath are common in the final days of life, affecting more than half of patients. Although the causes of dyspnea are diverse and often multifactorial, there are common approaches to management (Dudgeon and Rosenthal, 1996). The sensation of air hunger causes great anxiety, and the appearance of respiratory distress is traumatic for patient and family (Ahmedzai, 1998). Despite the prevalence of this devastating symptom, there are no formal clinical practice guidelines for its management in end-of-life care.

Palliation of dyspnea, if the underlying cause cannot be addressed, often depends on the use of opiates for cough control and the reduction of air hunger. The use of bronchodilators and oxygen can provide symptom relief depending on the etiology and pathological process. Respiratory secretions can be minimized with scopolamine and atropine if necessary.

Anxiolytics may also make an invaluable contribution in this setting, as may behavioral therapies to assist in relaxation. In the patient who is dying imminently, sedation with intravenous morphine may be most appropriate to treat the distress of severe air hunger. As mentioned earlier, Cheyne-Stokes respiration that often characterizes the final stage before death is especially disturbing to family members who feel that the rapid respiration alternating with apnea must be distressing, although patients are somnolent in this final phase of dying and interventions for comfort are not necessary. However, the suffering of those who care for them must be recognized and psychosocial support and education are essential. Families are often unprepared for the events and symptoms of the final days, and the trauma of this experience is magnified by the uncertainty about the future. Reassurance and education by the medical team are an important component of quality clinical care and can have an enormous impact on the family who otherwise is haunted during its bereavement by images of suffering.

Development and implementation of clinical practice guidelines for dyspnea is especially important, given both the high incidence of this symptom and its emotional impact. Further research on symptom management in the end of life will support evidence-based clinical interventions for terminal dyspnea.

Control of Physical Symptoms: Next Steps

-

Clinical practice guidelines for control of the common symptoms have, at present, been developed largely for the care of ambulatory and hospitalized patients. These must be modified to apply to end-of-life care. Excellent descriptive guides in the literature for symptom management at the end of life must be developed into algorithm-based clinical guidelines. Guidelines should be developed by a multidisciplinary panel to address the spectrum of physical symptoms common at the end of life, modifying and building on existing practice guidelines for symptom management.

-

Education of patients and families, using a practice guideline model, is needed to ensure their understanding of the common symptoms at the end of life and their management. This is essential to minimize distress and to reduce uncertainty and fears about the dying process.

-

Guidelines must be culturally sensitive and address the special concerns around treating underserved medical populations (e.g., non-English speaking, chronically mentally ill, religious, ethnic, and racial minorities).

-

Guidelines must be developed that ensure adequate symptom control to prevent the secondary development of depression and anxiety that further complicate overall management by the presence of greater distress levels.

-

Guidelines must provide for the concept of comprehensive end-of-

-

life care that integrates the treatment of both physical symptoms and distress in the psychosocial, spiritual, and religious domains, recognizing their interrelationship.

REFERENCES

Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. 1993. Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care. Vol. 1, Detection and Diagnosis. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 5. AHCPR Publication No. 93–0550. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

Ahmedzai S. 1998. Palliation of respiratory symptoms. In Doyle D, Hanks GWC, MacDonald N (eds.): Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (2nd edition). New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 583–616.

Almanza J, Holland JC. A review of literature on breaking bad news in oncology. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:135.

American Academy of Neurology. 1996. Report of the Ethics and Humanities Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology: Palliative Care in Neurology. Neurology 1996; 46:870–872.

American Board of Internal Medicine. 1996. Caring for the dying: Identification and promotion of physician competency. Educational Resource Document.

American Nursing Association. 1991. Position Statement on Promotion of Comfort and Relief of Pain in Dying Patients. Kansas City: American Nursing Association.

American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee. Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. JAMA 1995; 274:1874–1880.

American Psychiatric Association. 2000. APA Clinical Practice Guidelines for Psychiatric Disorders Compendium 2000. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

American Society of Clinical Oncology. Outcomes of cancer treatment for technology assessment and cancer treatment guidelines. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14:671–679.

Baile WF, Glober GA, Lenzi R, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. Discussing disease progression and end of life decisions. Oncology 1999; 13:1021–1028.

Bottomly DM, Hanks G. Subcutaneous midazolam infusion in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 1990; 5:259–261.

Braun KL, Pietsch JH, Blanchette PL (eds.) 2000. Cultural Issues in End-of-Life Decision Making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Kain M, Funesti-Esch J, Galietta M, Nelson CJ, Brescia R. Depression, hopelessness and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000; 284:2907–2911.

Buckman R. 1998. Communication in palliative care: A practical guide. In Doyle D, Hanks GWC, MacDonald N (eds.): Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine (2nd edition). New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 141–156.

Burt RA. The Supreme Court speaks: not assisted suicide but a constitutional right to palliative care. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1234–1236.

Callahan D. 1993. The Troubled Dream of Life: In Search of a Peaceful Death. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Carr JA, Payne R, et al. 1994. Management of Cancer Pain: Adults Quick Reference Guide. No. 9. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Carroll BT, Kathol R, Noyes R, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety in cancer patients using the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1993; 15:69–74.

Carver AC, Foley KM. 2000. Palliative care. In Holland JF, Frei, III E, Bast Jr. RC, Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum R (eds.) Cancer Medicine (5thedition). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: B.C.Decker; pp. 992–1000.

Cassel CK, Foley KM. 1999. Principles for Care of Patients at the End of Life: An Emerging Consensus Among the Specialties of Medicine. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund.

Cassem NH. 1997. The dying patient. In Cassem NH, Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Jellinek MS (eds.): Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry (4thedition), St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; pp. 605–636.

Chassin MR, Gavin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality: Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA 1998; 280:1000–1005.

Cherny NI, Portenoy RK. Sedation in the treatment of refractory symptoms: guidelines for evaluation and treatment. J Palliat Care 1994; 10:31–38.

Cherny NI, Coyle N, Foley KM. Guidelines in the care of the dying cancer patient. In Cherny NI, Foley KM. (eds.): Pain and Palliative Care. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 1996; 10:262.

Chochinov HM, Breitbart W (eds.). 2000. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chochinov HM, Holland JC, Katz LY. 1998. Bereavement: A special issue in oncology. In Holland JC (ed.): Psycho-oncology, New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 1016– 1032.

Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting D, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA 1983; 249:751–756.

Dudgeon DJ, Rosenthal S. Management of dyspnea and cough in patients with cancer. In Cherny NI, Foley KM (eds.): Pain and Palliative Care. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 1996; 10:159.

Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. What is accountability in health care? Ann Intern Med 1996; 124: 229–239.

Fallowfield L, Lipkin M, Hall A. Teaching senior oncologists communication skills: results from phase 1 of a comprehensive longitudinal program in the United Kingdom. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16:1961–1968.

Field MJ, Lohr K (eds.). 1990. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Field MJ, Lohr K (eds.). 1992. Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Fitchett G, Handzo G. 1998. Spiritual assessment, screening, and intervention. In Holland JC (ed.): Psycho-oncology, New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 790–808.

Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 1207–1221.

Ford LG, Hunter CP, Diehr P, Frelick RW, Yates J. Effects of patient management guidelines on physician practice patterns: the Community Hospital Oncology Program experience. J Clin Oncol 1987; 5:504–511.

Gallup G, Newport F. Mirror of America: fear of dying. Gallup Poll Monthly 1991; 304:51– 19.

Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news: consensus guidelines for medical practitioners. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13:2449–2456.

Grimshaw JM, Russell TI. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice. Lancet 1993; 342: 1317–1322.

Hastings Center. 1987. Guidelines on the Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment and the Care of the Dying: A Report. Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.: Hastings Center.

Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA 1997; 277: 333–340.

Holland JC. Preliminary guidelines for the treatment of distress. Oncology 1997; 11(11A): 109–114.

Holland JC (ed.). Psycho-oncology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Holland JC. NCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distress. Oncology 1999; 13(5A):113–147.

Holland JC, Almanza J. Giving bad news: is there a kinder, gentler way? Cancer 1999; 86:738– 740.

Hopwood P, Howell A, Maguire P. Screening for psychiatric morbidity in patients with advanced breast cancer: validation of two self-report questionnaires. Br J Cancer 1991; 64:353–356.

Ibbotson T, Maguire P, Selby P, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in cancer patients: the effects of disease and treatments. Eur J Cancer 1994; 30A:37–40.

Institute of Medicine. 1997. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Institute of Medicine. 1999. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Hewitt M, Simone JV, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Johanson GA. Midazolam in terminal care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1993; 10:13–14.

Karasu B. Spiritual psychotherapy. Am J Psychotherapy 2000; 53:143–162.

Katterhagen G. Physician compliance with outcome-based guidelines and clinical pathways in oncology. Oncology 1996; 10(11 Suppl.):113–121.

Kornblith AB, Holland JC: Model for quality-of-life research from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B: the telephone interview, conceptual approach to measurement, and theoretical framework. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1996; 20:55–62.

Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB. Daily interruption of sedative infusion in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1471– 1477.

Loscalzo M, BrintzenhofeSzoc K. 1998. Brief crisis counseling, In Holland JC (ed.): Psychooncology, New York: Oxford University Press; pp. 662–675.

Maguire P, Faulkner A. Communicate with cancer patients: 1. Handling bad news and difficult questions. Br Med J 19998; 297:907–909.

Maguire P. 2000. Communication with terminally ill patients and their relatives. In Chochinov HM, Breitbart W (eds.): Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000; pp. 291–301.

Massie MJ, Holland JC, Glass E. Delirium in terminally ill cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140:1048–1050.

McCann RM, Hall WJ, Groth-Juncker A. Comfort care for terminally ill patients: the appropriate use of nutrition and hydration. JAMA 1994; 272:179–181.

McGivney WT. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network: present and future directions. Cancer 1998; 82(10 Suppl.):2057–2060.

Mercandante S. The role of octreotide in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 1994; 9:406– 411.

Mercandante S, Kargar J, Nicolosi G. Octreotide may prevent definitive intestinal obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13:325–326.

Morris M. Implementation of guidelines and paths in oncology. Oncology 1996; 10(11 Suppl.): 123–129.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Second Annual Conference. Antiemesis practice guidelines panel presentation. Ft. Lauderdale, FL, March 2–5, 1997.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Fourth Annual Conference. Practice guidelines and outcomes data in oncology. Update: NCCN Distress Management Guidelines. Ft. Lauderdale, FL, February 26–March 2, 1999a.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Fourth Annual Conference. Practice guidelines and outcomes data in oncology. Cancer Pain. Ft. Lauderdale, FL, February 26–March 2, 1999b.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Fourth Annual Conference. Practice guidelines and outcomes data in oncology. Assessment of fatigue: New Measurement Scales. Ft. Lauderdale, FL, February 26–March 2, 1999c.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Panel. Doctor-Patient Communication (pending, 2001).

Parle M, Maguire P, Heaven C. The development of a training model to improve health professionals’ skills, self-efficacy and outcome expectations when communicating with cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 1997; 44:231–240.

Passik SD, Donaghy KB, Theobald DE, Lundberg J, Holtsclaw E, Dugan, Jr. WM. Oncology staff recognition of depressive symptoms on videotaped interviews of depressed cancer patients: implications for designing a training program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000; 19:329–338.