2

Reliable, High-Quality, Efficient End-of-Life Care for Cancer Patients: Economic Issues and Barriers

Joanne Lynn, M.D.

RAND Center to Improve Care of the Dying

Ann O’Mara, R.N., Ph.D.

Bethesda, MD

INTRODUCTION

Living with, and eventually dying from, a chronic illness ordinarily runs up substantial costs for the patient, family, and society. Patients are sick, dependent, changing, and needy. Indeed, more than two dollars of every eight spent in Medicare is spent in the last year of life, and one in every eight is spent in the last month (Lubitz and Riley, 1993). Those with cancer have approximately 20 percent higher than average costs (Hogan et al., 2000).

High costs probably would be acceptable to all if patients and families were satisfied with the care provided for those with advanced disease, but few can count on being satisfied. Reports of inadequate symptom relief, uncertain responsibility for patient care across multiple care providers, family disruption and financial distress, inadequate planning ahead for serious disability and death, and other shortcomings are commonplace (IOM, 1997). In short, our society is spending a great deal and not getting what dying cancer patients need.

Many factors contribute to these shortcomings: inadequate attention to the problems, untrained professionals, absent quality standards, and so on. This chapter addresses the contribution to the shortcomings made by the financial arrangements covering care for people with advanced cancer. Changes in financing and coverage will not, on their own, change the standards of care (Vladeck, 1999), but changes in financing and coverage are an essential part of sustainable, comprehensive reform. Engineering a

society for better performance requires paying for the essential services at least well enough to allow their providers to make a living. Indeed, financial incentives probably shape professional and public definitions of appropriate care in ways that are hard to trace or to correct. However, understanding these incentives and the distortions they engender is essential when aiming to engineer effective reform.

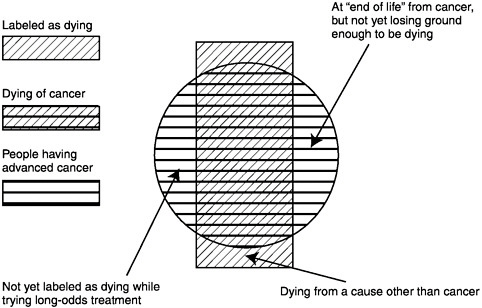

Briefly, the population of concern is those persons who have advanced malignancy (solid cancers, hematologic malignancies, brain tumors, and others) at such a stage that the patient does not feel well on his or her usual day and the malignancy is not expected to remit substantially before contributing to the patient’s death. Not all such patients are given the label of “dying.” For example, those who may live many years with an indolent cancer, like the usual prostate cancer, or those with a small chance of remission from ongoing aggressive treatment, might not seem to be dying. Furthermore, not all dying cancer patients actually fit this definition; those with other serious conditions that are likely to cause death before the cancer would might well be dying, though their cancer is only a minor problem (Figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1 The population with advanced cancer.

Once, virtually every serious illness, including cancer, spelled a fairly rapid course to death. Malignancies were identified only when large or in a critical location, and most often, no treatments were available that substantially altered the course. The fact that cancer patients often lingered a few months, often with disturbing appearance, odors, and suffering, undoubtedly contributed to cancer’s special position of abhorrence in the popular mythology. Now, patients with cancer often live much longer because of better prevention, earlier diagnosis, and treatments that prolong survival, resulting in longer periods of adaptation to cancer as a chronic debilitating disease. However, most still eventually die from the cancer. In fact, mortality from lung, breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, for example, is not much better than it was 50 years ago (ACS, 2001). Most, too, face discontinuities and other lapses in quality of care at the end of life.

The fact that many will suffer at the end of life from the shortcomings of current care patterns probably arises mostly from our inexperience, as a society, with our new circumstances. As part of our collective inexperience, we have not settled upon language, categories, or methods that serve us well. We persist in talking of “terminal cancer” or “the shift from cure to care” as if these were obvious, natural categories, though they are not. Myriad studies of treatments use prolonged survival as the end point; in contrast, only a handful of studies aim to find ways to improve quality of life, opportunity for life closure, family togetherness, financial well-being, or symptoms.

This chapter describes the following general findings and offers suggestions as to how to improve the experience of end-of-life care for patients with cancer:

-

End-of-life care is unavoidably expensive, largely because people are very sick.

-

The services most needed are often not covered by Medicare or other insurance, and the services most well-covered may well be overused.

-

The transfers that patients endure among care providers might be much more avoidable if continuity were valued.

-

The Medicare hospice program could be modified in various ways to improve its usefulness.

-

Very little reliable and generalizable information advances the discussion of financing of end-of-life care.

Since we are focused upon those at the end of life, this chapter does not deal with the costs of diagnosis or initial treatment, and since the focus is on cancer care, it does not deal with the effects of comorbidities, although the economics of both earlier care and care of other conditions profoundly affect the economics of cancer care.

CURRENT FINANCING OF ADVANCED CANCER CARE

Private insurance or Medicare covers most of the medical care expenses of people with advanced cancer. Most people with Medicare coverage have expanded benefits (through Medicaid, private pensioners’ insurance, or Medigap insurance) that often cover some prescription drugs (Commonwealth Fund, 1998) and also cover most of the deductibles and coinsurance. Since Medicare is the largest and the only nationally uniform coverage plan and the majority of people with cancer are over 65, Medicare will be used as a prototype.

Medicare Coverage and Design

Medicare (in fact, most health insurance) was constructed mainly to make surgery available, and its coverage and financing rules reveal those roots. Although managed care has been introduced and covers a growing portion of the Medicare population, most Medicare payment is currently in the fee-for-service system, in which payment arises as reimbursement for services already given. Medicare fee-for-service provides reasonably well for procedures needed for diagnosis and treatments aimed at disease modification. Coverage extends not only to surgery, radiation treatment, diagnostic testing, and in-patient hospitalization, but also to intravenous medication, skilled nursing for the homebound and those in nursing facilities, oxygen (for those with severely low oxygenation), and durable medical equipment. Medicare also offers hospice; indeed, Medicare pays for 65 percent of all patients receiving hospice care in the United States (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2001). However, Medicare was originally established for diagnosis and treatment of diseases. The language of the hospice benefit (and the parallel language in the preventive services benefit added later) can be read to imply that assuaging symptoms and supporting the very sick was not part of the original Medicare mandate. Since clinical practice has moved strongly toward incorporating palliative care into routine health care, this interpretation may become irrelevant. However, it may also eventually require modification of the enabling statute.

Medicare (and most insurance) does not generally pay for medications that the patient can take on his or her own, personal care assistance, or disposable supplies. These restrictions are felt all the more keenly with the shift of cancer care to the outpatient setting, greater demands on family caregivers to administer both oral and parenteral medications, and the increasing use of home-delivered chemotherapeutic agents. Furthermore, fee-for-service payments generally have incentives contrary to continuity and do not pay for institutional care outside of hospitals.

A small proportion of Medicare patients and a larger proportion of younger patients are in capitated care systems, in which a provider or insurer receives a set amount of money each month for every member regardless of how much care is provided. In general, these arrangements do not pay the fiscal risk-taking entity better for a patient who is sick, since rates are set “per capita” for a population. (Risk-adjusted payments are being implemented in the Medicare capitated payment system; Iezzoni, 1997). However, capitation also allows much more flexible use of the funding and thus can cover medications, personal care, and other elements not generally covered in Medicare fee for service, if the insurer decides to offer those benefits (to attract enrollees). Capitation undoubtedly creates pressures to reduce services generally, but the one careful study of the effects of provider or payer type on the costs of the last year of life for the frail elderly found no differences between Medicare health maintenance organizations (HMOs), traditional fee for service, and Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibles (in California, in 1990–1993) (Experton et al., 1999).

Innovative approaches that combine elements of these approaches are not hard to find. Some benefits managers are “carving out” care of cancer patients and handling them as a separate capitation to specialists, for example.

Hospice

The most substantial innovation to serve advanced cancer patients is hospice. The Medicare hospice benefit mostly pays the hospice provider organization a daily rate for each patient enrolled and served at home. A small proportion (by law, less than 20 percent) of the days that Medicare pays to hospice providers can cover continuous nursing care, inpatient respite stay, or inpatient symptom management. The services that hospices provide include many elements that are not typically part of Medicare coverage: for example, interdisciplinary team, care planning, personal care nursing, family or patient teaching and support, chaplaincy, medication (with a small copayment), counseling, symptomatic treatment, and bereavement. The attending physician services either are paid within the hospice benefit (if the physician is a hospice employee) or are paid upon a separate billing from the physician to Medicare.

Hospice pioneers did not envision hospice as a part of routine health care, although this is what it has become. More than half of Medicare beneficiaries dying with a cancer diagnosis used at least some hospice care in 1998 (Hogan et al., 2000). However, the ways in which hospice programs are not parallel to (or integrated with) other health care programs are evident. For example, under Medicare, hospice programs may serve only patients enrolled specifically in the hospice benefit (which restricts

other types of care they can receive, as discussed below). Even if hospice skills would be useful to other patients, no payment is available, and in some circumstances, the services cannot even be provided for free (since it might amount to an illegal inducement to enroll).

As another example, the interface of hospice services and nursing home care has been quite unsettled. Only a minority of nursing home patients has their stay reimbursed by Medicare (only after a qualifying hospitalization and if requiring skilled services). In general, Medicare reimbursement for skilled nursing home stays is high enough that the few patients who do qualify are not even offered the opportunity to enroll in hospice (only either skilled nursing home care or hospice can be in effect at one time). However, most nursing home stays do not qualify as “skilled” and thereby do not qualify for Medicare payment. These patients are often eligible for hospice services if a qualified hospice works out a relationship with the nursing home.

However, two problems complicate the integration of nursing home reimbursement and hospice. First, both the nursing home and the hospice are independently required to establish and implement a plan of care, and it is not clear how conflicts should be resolved. In addition, most such nursing home stays end up being paid by Medicaid. This could offer an opportunity for paying almost double the nursing home rate (by adding the hospice benefit payment to the nursing home payment). Many observers were skeptical that such patients would receive twice as much service, thus raising the possibility of improper profits. While the situation is unstable, the current resolution is that a Medicaid-enrolled patient in a nursing home (who is not using Medicare skilled nursing facility benefits) who is also eligible for hospice can enroll in hospice if the nursing facility and the hospice have a legal agreement as to their responsibilities, the hospice provides certain core services directly, and the hospice accepts the full payments from Medicaid and Medicare and pays the nursing home.

When hospice started in this country, it was a movement that rejected mainstream medicine. The Medicare hospice benefit perpetuated this concept by making hospice quite separate from the rest of health care. Now that hospice is used as mainstream care, unanticipated troubles arise from the many dysfunctional junctures between hospice and the rest of health care, such as the interface with nursing homes or patients still not in hospice care.

Once committed to hospice care, the major problems that affect most patients arise from

-

restrictive and varying enrollment criteria,

-

substantial variation in service array and financial risk taking across hospices,

-

short stays, and

-

increasingly costly options for palliative care.

Hospice Enrollment Criteria

Medicare allows hospice enrollment only for patients with a “prognosis of less than six months” who formally consent to forgo curative medical care. These requirements ensure that hospice enrollment is seen as a substantial decision to pursue a death-accepting course. The sense that one is giving up on hopefulness makes some patients resist enrollment.

The hospice requirement of a six-month prognosis has itself been quite troubled. Oddly, the requirement has never been defined. Is the “just barely qualified” patient just “more likely than not” to die within six months, or should that patient be “virtually certain to die”? This may sound like an arcane issue, but the population that includes everyone who is more likely than not to die from a chronic disease within six months is probably two to three orders of magnitude (100 to 1,000 times) larger than the population of persons who can be known to be virtually certain to die. In addition, requiring virtual certainty also engenders eligibility for hospice only within a few days or weeks of death, since our prognosticating ability is simply not precise enough to allow confident prognosis until the patient is visibly failing, bed-bound, and worsening daily (Fox et al., 1999; Lynn et al., 1997).

Fraud investigations for long-stay hospice patients in the past few years have induced an attitude of caution and a reticence to take on patients who might stabilize and live a long time. Until these fraud investigations, when a very sick patient did stabilize and live, most hospices would just keep the patient enrolled, knowing that the illness would eventually worsen again and cut life short. Now, such patients are likely to be discharged from hospice. Their “next-best” service array is often quite limited (as discussed below).

Providers and patients expect much the same services to be available from all programs within each kind of provider. For example, we expect every hospital to have a laboratory and X-ray facilities, operating rooms, inpatient beds, and so on. Indeed, we expect that most hospitals would profess their own competence and scope in just about the same ways as other hospitals. Hospices are different. Right from the start, they were allowed to define their own scope of practice, within broad boundaries. Thus, some hospices will not take patients using feeding tubes, while others not only will take those patients but would also allow tests and medications to keep a patient eligible for transplantation. Some hospices won’t take any patient on “chemotherapy,” but others will try to accept those with “palliative” treatments (but not those “still aiming at cure”). These terms have

become quite difficult to define, but the point here is that, as long as they are honest with patients and others, hospices are free to define their scope of service and enrollment criteria and thereby to limit or expand their financial risks.

This has led to neighboring hospices having quite different practices, populations, and skills. Since they all are paid the same capitation, this also translates to very different foci. Some hospices limit themselves to rather simple medications and limited physician services, for example, and therefore may be more able to provide home health aides. Other hospices are committed to providing whatever treatments the patient and physician think might be helpful. Since the treatments are often costly, these hospices might have much less flexibility to serve psychosocial needs.

In addition, hospices are very different in size. Roughly 30 percent of hospice days are in hospices that are of substantial size—more than 150 patients on the usual day. However, these patients are being served by only about a score of hospice organizations. The other 3,100 hospices mostly serve less than 50 patients on any given day (Stephen Connor, National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, personal communication, July 13, 2000). Large hospices are more able to take risks and accept patients who might be exceedingly costly. Managers of small hospices realize that one patient with extreme costs would spell financial disaster. These differences are not usually apparent to patients or referring physicians, who may end up seeing differences among hospice programs as simply erratic, unpredictable, and idiosyncratic.

Hospices are bedeviled now with short stays. In 1998, the mean length of stay was 51.3 days and the median length of stay was 25 days (National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, 2001). In 1990, the mean was nearly 90 days and the median was 36 days (Christakis and Escarce, 1996). Various observers attribute short stays to different causes, including physician and patient reticence to stop active treatment; more treatment options for second-, third-, and fourth-line treatments (e.g., Herceptin, Rituxan, erythropoietin); hospice reticence to enroll patients receiving expensive treatments (even if acknowledged to be palliative); prognosis becoming clear only when death is close (especially in non-cancer diagnoses); and new populations coming into hospice (incompetent persons, very elderly persons, noncancer fatal illnesses, and others). No reliable research has yet sorted out the reasons for increasingly short stays in hospice. However, the financial impact has been substantial. The first day or two in hospice are always costly, as the hospice team gets to know the patient and family, puts needed equipment and medication in the home, and monitors progress with new plans of care. Likewise, the last few days of life are expensive, as the patient and family need more care, more frequent changes in medication, help with declaring death and arranging for the care of the body, and

support through at least a year of bereavement. When these days come close together, there are no “stable” days in which costs might often be lower than the daily rate. Thus, short stays threaten the financial viability of hospices.

Hospices are also struggling with a plethora of developments in palliative care. Twenty years ago, it was not much of an exaggeration to claim that the hospice physician could do most everything with little more than cheap opioid medications, steroids, diuretics, and antibiotics. Now, patients are served somewhat better by more technologically advanced interventions, more expensive medications, more use of radiation or surgery, and so on. For example, for some patients, pain could be suppressed with oral or subcutaneous morphine, with the side effect that the patient would be groggy and perhaps sometimes confused. Better alertness and pain control might be possible with an intrathecal pump for morphine, at an initial cost of about $20,000.

Other examples are common. Gemcitabine measurably reduces pain in pancreatic cancer and has been reported to have superior antitumor activity and improved survival over 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; Ulrich-Pur et al., 2000), at a cost of about $500 per week. Many patients with advanced cancer also get pulmonary emboli or thrombosis of the leg veins. Standard treatment with anticoagulants entails certain risks and annoyances that are largely avoided by low-molecular-weight heparin injections. However, the standard treatments cost only a few dollars per day (after initial hospitalization, which is covered by Medicare), while the low-molecular-weight heparin costs about $60–$120 per day it is not covered by Medicare unless a hospice program decides to pay for it from the hospice per diem. Because this is financially unsustainable, medications and interventions that are this costly and are not covered by insurance are largely unavailable. In contrast, if covered by insurance, they are readily available, even if a thoughtful assessment would raise doubts about the merits of investing so heavily in small gains for persons with short life expectancies.

Gap Between Hospice and Home Care

Many patients simply have no Medicare-covered services for a part of their course when they are quite needy but are neither so sure to die within six months that hospice is available (or they are otherwise ineligible for their local hospice) nor so housebound as to qualify for the limited help from Medicare home care (which requires being unable to leave the home except for physician visits). Physicians and nurses are probably fairly customer oriented for this needy group and offer ways to get them some of the services they need (e.g., by short-term certification of homebound status).

The impact of this distortion and the unmet need has not been estimated in the published literature, however.

DESCRIPTION OF COSTS AND COST-EFFECTIVENESS OF TREATMENTS

About half a million patients in the United States die of cancer each year (American Cancer Society, 2001), and on average, about $32,000 per patient is spent in the last year of life for the care of Medicare patients dying of cancers (Hogan et al., 2000). The care of cancer is a major part of the business of health care, and many businesses and provider organizations focus exclusively on cancer care. Most literature on diagnosis, treatment, and cost does not address the entire cancer population, but addresses just one type. Thus, this section reviews descriptive accounts that address costs and cost-effectiveness of treatments offered for particular common cancers and then for symptom management and palliative care more generally.

Advanced Lung Cancer (Non-Small Cell Cancer of the Lung)

In contrast to breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, very little progress has been made in early diagnosis and long-term remission in lung cancer. Furthermore, as the most common cancer among men and women in the United States, lung cancer accounts for approximately 20 percent of all cancer care costs (Desch et al., 1996). The focus of clinical trials has been to prolong survival and increase the number of one- and two-year survivors. Recently, attention has turned to economic evaluations that compare the cost and benefits of such treatments. In their review of the available economic data, Goodwin and Shepherd (1998) conclude that the costs of combination chemotherapy or combined-modality treatment for locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer are well within the range considered acceptable for interventions used for other diseases.

Smith (Thomas J.Smith, personal communication, 2000) proposed asking about the patient’s evaluation of the merits of treatment in this disease in a quite novel and illuminating way. Working with a large regional insurer, Smith generated actuarial estimates of the expenditures from diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer through to death. He proposed to give the patient a choice, after giving the patient a solid understanding of the issues at stake. The patient could choose to have conventional care, with treatments that would probably extend life (for three to four months, on average), or the patient could choose to have hospice care available from the start and also take all of the funds (about $19,000) that would probably have been spent on his or her radiation and chemotherapy. The experiment

was terminated after six months, largely because few patients remained outside of managed care plans by the time all of the preliminary arrangements were in place (and the experiment required that patients be in conventional fee for service). However, the mental model is quite illuminating. Would people who had to pay their own bills remain willing to get treatments with small expected gains? Some are quite offended by Dr. Smith’s experiment, claiming that it is offensive to consider life in monetary terms. This objection, if widespread, will be difficult to accommodate in policy.

In 1992, the charges for hospitalization in the last year of life for lung cancer patients dying in a hospital in Connecticut averaged $40,000, while those who died at home or in hospice had hospital charges of about $30,000 (Polednak and Shevchenko, 1998). Smith suggests that a fairer comparison would be average total health care costs, rather than limiting it to hospital charges.

Advanced Colorectal Cancer

Evaluating the costs of treating patients with advanced colorectal cancer has been the subject of various research endeavors, most of them outside the United States. Chemotherapy, concomitant medications, surgical procedures, hospitalizations, diagnostic tests, and outpatient visits have been assessed for their economic merit (Cunningham, 1998; Glimelius et al., 1995; Neymark and Adriaenssen, 1999; Recchia et al., 1996; Ron et al., 1996; Ross et al., 1996; Scheidback et al., 1999; Torfs and Pocceschi, 1996). A 1996 U.S. study compared two common protocols (intensive-course 5-FU+low-dose leucovorin versus weekly 5-FU+high-dose leucovorin), including financial cost as an end point (Buroker et al., 1994). Therapeutic efficacy was similar between the two schedules, both groups experienced distinct dose-limiting toxicities, and financial costs were higher for the weekly dose due to increased hospitalizations to manage toxicities. The hospitalization expenses for the weekly protocol ($3,240 per patient) were nearly double those for the intensive-course protocol ($1,781) for 32 weeks of chemotherapy (1994 dollars).

Brown and colleagues (1999) developed an illuminating method for describing costs. They split each patient’s course into three parts: initial phase (first 6 months), terminal phase (last 12 months), and continuing care (whatever is left in the middle). They also estimated cancer-related costs and other medical costs by comparing matched control patients. The terminal phase in 1990–1994 had cancer-related costs of $15,000; the overall course had cancer-related costs of $33,700 and about an equal amount for noncancer-related costs.

Advanced Breast Cancer

Recent preliminary reports from several large trials show that the rigorous and costly regimen of high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue for metastatic breast cancer probably offers no survival advantage over standard chemotherapy (Peters et al., 2000). Given the lack of a clear, definitive answer to the question, a number of different chemotherapeutic regimens and doses, as well as the timing of these agents, are continuing to be investigated. Eight years prior to these reports, Hillner and colleagues had shown that autologous bone marrow transplant versus standard chemotherapy in a hypothetical cohort of 45-year old women with metastatic (Stage IV) breast cancer increased life expectancy by six months, using a five-year horizon. However, it came at a considerable cost of $115,800 per year of life gained. They also demonstrated that if the cost of the transplant procedure could be reduced, the cost per life-year gained could be improved to $70,000 (Hillner et al., 2000).

One of the most common metastatic sites in breast cancer is bone, resulting in additional treatment costs for pain management, such as narcotic analgesics or radiation, and surgery to treat bone fractures. On the other hand, many bony lesions are asymptomatic, often found on routine follow-up. Consequently, a balance must be achieved between expending undue resources to find asymptomatic lesions and necessary efforts to prevent or reduce complications. One approach to reducing the risk of complications has focused on the role of bisphosphonates, specifically pamidronate. A post hoc evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of pamidronate revealed that although it was effective in preventing skeletal related events (SREs), the total costs of administering pamidronate far exceeded the cost savings from avoided SREs, which included pathologic fractures, spinal cord compression or collapse, radiation for pain relief, and hypercalcemia. In addition, 80 percent of the projected costs of pamidronate per treatment were due to the drug’s costs. The 1998 monthly estimated cost of pamidronate therapy was $775 (Hillner et al., 2000).

Hospital charges for breast cancer patients who died in 1992 in a Connecticut hospital averaged $42,000, while the costs for those who died at home or in hospice care averaged $20,000 (Polednak and Shevchenko, 1998).

Advanced Prostate Cancer

Finding the most effective therapy, both medically and financially, for relieving pain related to metastatic prostate cancer has been a major focus of recent research (Beemstrober et al., 1999; Bennett et al., 1996; McEwan et al., 1994; Shah et al., 1999). Medicare reimbursement policies play a

troubling role in physician decisionmaking with regard to new modalities for metastatic prostate cancer. Flutamide, a nonsteroidal antiandrogen, may be effective in prolonging the time to progression of disease, improve overall survival, and have a favorable cost-effectiveness profile (Bennett et al., 1996). Because it is an oral medication, Medicare does not cover it. Findings from physician focus groups indicated that the potential out-of-pocket expenses incurred by patients influenced doctors’ prescribing practices and recommendations for or against patient enrollment in flutamide clinical trials (Bennett et al., 1996).

In 1991, the total Medicare payments for prostate cancer care from diagnosis to death (seven years) averaged about $49,000 (Riley et al., 1995). Lifetime lung cancer costs are lower ($29,000), but the longer survival period in prostate cancer ends up costing more in aggregate.

Symptom Management

Pain continues to be the most frequent unrelieved symptom in the advanced cancer patient (Ingham, 1998). As cancer patients approach death, their initial oral analgesic may become inadequate. Although reasonable control could usually be regained with substantial dosage increases, different opioids, routes of administration, and delivery systems often provide more reliable control with fewer side effects. However, advanced pain treatments, such as pamidronate and intrathecal pumps, can greatly increase the cost. Furthermore, Medicare does not generally pay for pain management medications (IOM, 1999). The typical cost for an implanted intrathecal opioid infusion is $23,000, which includes hospitalization and professional fees (G.Fanciullo, personal communication, 2000). This may seem inordinately high, in light of the availability of less expensive modes of pain therapy. Yet, the complexity of the patient’s condition might well lead the clinician to choose the implanted intrathecal approach. In their case report, Seamans and colleagues (2000) found it more cost effective to use intrathecal therapy (total estimated cost at three months, $19,645) over a systemic analgesic therapy (total estimated cost at three months, $31,860).

Home management of terminally ill patients could potentially contribute to decreased costs. A retrospective Canadian study compared the cost of managing cancer patients who required narcotic infusions in hospital and at home. Medical costs, in 1991 Canadian dollars, averaged $370 per inpatient-day and $150 per outpatient-day (Ferris et al., 1991). Other symptoms or advanced cancer complications for which health care resources are used include constipation (Agra et al., 1998; Ramesh et al., 1998), dyspnea (Escalante et al., 1996), common bile duct obstructions (Cvetkovski et al., 1999; Kaskarelis et al., 1996), intractable vomiting (Scheidbach et al., 1999), and dehydration (Bruera et al., 1998).

The assortment of clinical trials focused on symptom management and related costs does not accurately reflect the reality of clinically managing terminally ill cancer patients. Aside from the pain management studies that included associated costs, the costs of other frequently occurring debilitating symptoms of dyspnea, diarrhea, constipation, seizures, and terminal delirium have not been assessed adequately. Not only do we know little about how much it costs to treat these symptoms, we know equally little about the costs to society when they are mismanaged, as they often are.

An interesting associated issue arises with the off-label use of therapies that are thought to be helpful to suffering patients. An intriguing example might be erythropoietin alfa (Epo), which is used for cancer-related anemia. Epo is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for various indications, but the only cancer indication for Epo is for patients with nonmyeloid malignancies who are concomitantly receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Physician prescribing is not limited to FDA-approved indications, however, and many cancer patients not receiving chemotherapy, or receiving chemotherapy that is not myelosuppressive, are prescribed Epo for anemia. Although lack of FDA approval is not always synonymous with a lack of evidence of effectiveness, in this case, there have been no trials in the general population of cancer patients, so effectiveness has not been demonstrated. Only one active National Cancer Institute (NCI) Phase III clinical trial is exploring the effect of Epo in anemic patients with advanced cancer undergoing platinum-containing chemotherapy. Nonetheless, it is an approved drug that is covered by Medicare, which paid $210 per injection in 1998. In 1998, about 35 million injections were given to about 2 million Medicare patients, at a cost of about $7 billion. If Epo is given in the hospital, it is part of the diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment for each stay, but if it is given in doctor’s offices, it is a separate covered expense. Either way, it is free to the patient. It has few side effects, beyond the cost.

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING STUDIES REPORTING COSTS

Assessing Costs and Effectiveness

For a few discrete advanced cancers and their symptoms, we know that certain treatments will not provide an improved quantity or quality of life and may be costly as well (Smith, 2001) (Table 2-1). One example of this is second-line chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer, which entails the use of fairly expensive drugs and a number of toxicities. On the other hand, we know very little about the most efficacious, least costly treatment for the full spectrum of advanced cancers. Indeed, little discussion illuminates the

TABLE 2-1 Targets for Reduction in Resource Use with No Impact on Quantity or Quality of Life

|

Strategy |

Comment |

|

2nd -line chemotherapy for metastatic cancer |

For instance, 2nd line chemotherapy with docetaxol improves overall survival and health-related quality of life in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Unclear if 3rd or other lines of chemotherapy have a similar effect. Most cancers have not been studied to see if 2nd or 3rd line chemotherapy is better than supportive care. Current NCCN guidelines call for switch to hospice or palliative care when chemotherapy has been tried and failed, and provide a starting point for “stopping rules.” For instance, current NCCN guidelines call for 2 types of chemotherapy in breast cancer, then switch to hospice care. The average patient receives far more types of chemotherapy. |

|

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for many solid tumors |

Proven modest benefits in resected gastric cancer, head and neck cancer, lung and esophageal cancers. For other cancers, there has been minimal impact on disease, and a marked increase in drug costs and toxicities. |

|

Radiotherapy palliation of bone and other metastasis |

1–5 fraction radiotherapy offers pain relief to the majority of patients and reduces the travel and treatment costs. |

|

Radiotherapy palliation of advanced lung cancer |

8Gy in 1 fraction or 16 Gy in 2 fraction offers symptom relief to the majority of patients and reduces travel and treatment cost; much higher doses are often used. |

|

Carcinoembryonic Antigens (CEAs), CA 27.29, CA 15.3 blood tests; bone scans, liver ultrasounds, chest X-rays, computerized axial tomography (CATs) and other follow-up tests in breast, lung, and colon cancer |

With the exception of the CEA in resected colorectal cancer, these tests offer no advantage in life-years saved, and the cost is prohibitive (for instance, estimates of follow up costs for breast cancer alone are over $1 billion annually), these tests are not recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology; for details see the website at www.asco.org and go to the “People Living with Cancer” section. |

|

Discuss “code status” with all patients while they are stable, and document whether resuscitation and ICU stay is medically indicated or desired by the patient and family |

The majority of physicians have acted against their conscience in providing aggressively futile care; this costly and tragic waste can be prevented by addressing the issue beforehand. |

|

Consolidation of provider visits, with switch to a primary care provider |

Patients may see a radiotherapist, surgeon, medical oncologist, and their primary care physician; only one is necessary, and the primary care provider may be less likely to order low-yield, high-cost diagnostic tests. |

|

Thomas J.Smith, personal communication, 2001. NCCN=National Comprehensive Cancer Network. |

|

question of how we ought to assess costs, efficacy, or the balance between them. Should oncologists be concerned about the costs of two efficacious treatments that are roughly equal, where one is far more expensive than the other? What about two treatments that have discernible but modest differences in efficacy and substantial differences in costs? As Smith and colleagues have wryly noted, “If oncologists do not work to determine the efficacy and cost effectiveness of cancer treatment, others will do it for them” (Smith et al., 1993). Of course, it may be that oncologists should insist upon others doing this work. Perhaps societal or personal values are what should matter, and oncologists may have no special insight into these matters. Either way, we have no method by which to weigh these issues and to implement any ensuing judgments.

Even defining “cost” turns out to be a difficult endeavor. It cannot be confined to the costs of the particular treatment modality because each treatment has side effects and toxicities and may require different settings for treatment or for living. Yet, to date most research has focused on the cost of medications and insurance-covered medical care.

The many physical, emotional, and financial burdens families take on when caring for loved ones are beginning to be noted in counting costs. The metric for measuring the subjective components of caregiver burdens is quite unsettled. The complexity of human situations seems hard to capture in a single scale that would allow comparisons, for example, of the burdens incurred by an elderly wife caring alone for her aged husband who is dying slowly of metastatic prostate cancer with the burdens felt by a large extended family supporting a younger man dying with very difficult suffering from lung cancer.

Smith and colleagues pose the question of whether palliative cancer care can be cost-effective, at least as that is now operationally defined. For many cancers, palliative therapy may be as expensive as chemotherapy (Smith et al., 1993). However, the end points for palliative therapy, although definable in terms of symptom control and quality of life, are not easily quantified. Hillner and colleagues (2000) believe that the recurring challenge for both cancer and noncancer therapies is to establish the financial value of new medical interventions that are not associated with improved survival.

Paucity of Attention to Costs or Quality of Life in Clinical Trials

Until recently, the gold standards for determining the efficacy of a cancer treatment in a clinical trial have been improved survival, tumor shrinkage, and ultimately, cure. As more costly treatments enter the picture, more attention is being given to the economics of cancer therapies. In addition to the absolute costs of the treatments themselves, increasing num-

bers of procedures used in cancer therapy and the aging of the population contribute to the overall costs of cancer treatment (Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 1998). While improved survival has resulted for individuals diagnosed with early-stage cancers, eventually succumbing to the disease continues to be a likely outcome for many.

As the scope of clinical trials broadens to include individuals with late-stage disease, improved survival and tumor response remain the primary end points. Clearly, these end points are insufficient for this population. Researchers and clinicians are beginning to identify as end points the distressing symptoms of advanced cancer. The National Cancer Institute provides a comprehensive list of the six different categories of clinical trials— treatment, prevention, diagnostic, genetic, screening, and supportive care —on its Web site (http://cancernet.nci.nih.gov/cgi-bin/srchcgi.exe). A search of the supportive care category revealed 90 ongoing Phase II and III clinical trials. The primary end points were toxicity profiles, side effects, response rate, maximum tolerated dose, dose-limiting toxicities, event-free survival, and pharmacokinetic profile. Only a few studies aimed for other end points. Among the 38 Phase II trials, 7 explored quality of life (QOL) and/or symptom relief as primary or secondary end points in the advanced cancer population. Among the 52 Phase III trials, 13 specifically addressed QOL or symptom management or relief (pain, diarrhea, sleep disturbances, toxicities), in addition to tumor response and survival time.

Irrespective of the physiological or behavioral end point, financial considerations are rarely primary or secondary end points in clinical trials. None of the NCI supportive care clinical trials listed cost as an end point. A MEDLINE search of clinical trials about pain published over the past 10 years in the advanced cancer population yielded 265 trials. However, when cost, cost-effectiveness, health care costs, or economics was entered as a search term, only five remained. An even smaller proportion of advanced lung cancer trials (7 out of 725) listed these financing terms. In both types of studies, financial considerations were most often merely cursory commentaries, not study end points. Given the disturbingly high number of distressing symptoms afflicting the majority of the terminally ill cancer population, much more attention must be given to cost-effective symptom management modalities.

Generalizability

The generalizability of findings from advanced cancer clinical trials is also problematic, particularly with respect to age. Cancer has often been labeled a disease of aging, with estimations of a 10-fold increased likelihood of being diagnosed with cancer for those over 65 than for those under 65. Yet the median age of participants with advanced cancer in clinical

trials is almost always many years under 65. For example, the median age of women with metastatic breast cancer participating in two randomized trials that evaluated pamidronate in preventing bone complications was 57 years (Hillner et al., 2000). This is in marked contrast to the 1988–1992 age-adjusted incidence rates of 72.8 per 100,000 for women under 65 and 445.4 per 100,000 for women over 65 (Kosary et al., 2000). The data available for policy are built on a population that is at least a decade younger than the population actually facing these illnesses. This is important because the financial and family resources, physiological reserves, and comorbidities of younger persons are dramatically different than they are in older persons. The burgeoning size of our over-65 population demands that research deal with this target population, especially when the data are used for Medicare policy.

Other considerations make the generalizability of published studies quite problematic. Most studies are carried out in academic centers, which serve populations quite different from random samples. Most require patients who are able to travel and to consent, which eliminates many with cognitive disability or severe poverty. Most also require that the patient have no other serious or life-threatening disease.

Complex Role of the Patient’s Setting

As an alternative to aggressive, often futile, expensive therapy requiring repeated hospitalizations, increasing numbers of terminally ill cancer patients are enrolling in hospice or other home care. By opting for hospice or extensive home care, patients commonly remain at home among loved ones, receiving care that is focused on their symptoms, emotions, spiritual concerns, and family.

However, the long-held assumption that hospice care can contain costs at the end of life is being challenged on a number of fronts. These supposed benefits were among the reasons for hospice becoming a benefit in the Medicare program in 1983. Early research appeared to confirm this (Brooks, 1989a, 1989b; Brooks and Smyth-Staruch, 1984; Kidder, 1992; Mor and Masterson-Allen, 1990). Kidder estimated that during the first three years of the hospice benefit program, Medicare saved $1.26 for every dollar spent on Part A expenditures. Mor and colleagues examined data from the National Hospice Study to assess the time in the hospice program that would be the most informative period for which to evaluate associated costs. Enrollment periods of one to three months tend to yield the most savings (Brooks and Smyth-Staruch, 1984; Kidder, 1992). However, when the time period extended six months and beyond, the savings were not substantial. The National Hospice Organization commissioned a study that found that hospice saved $1.52 for every $1 spent by Medicare (Lewin-VH1, 1995).

This study was, however, largely uninterpretable because the key comparison was between cancer patients who had used hospice and those who had not. Even with a multivariable modeling technique, the comparability is uncertain. Furthermore, these data are now outdated, having focused on patients who died in 1992, and much has changed since that time. Since Medicare Part A and B expenditures cover less than 50 percent of medical care costs for patients over 65, examination of Medicare claims alone also limits our full understanding of the potential savings or costs of hospice enrollment.

Recent unadjusted comparisons (Hogan et al., 2000) showed that the total costs of care (from the Current Medicare Beneficiary Survey) were not significantly different, although Medicare’s proportion of payment was higher for hospice users. Emanuel addressed the question of whether better care at the end of life would generally reduce costs (Emanuel, 1996). Using his assumptions and estimates, hospice and advance directives might save 25–40 percent of the last month’s costs and 10–17 percent over the last six months. A recent analysis for the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) showed that patients who used hospice tended to be high-cost users before hospice enrollment (at the least, they did not include any very low cost users) and their costs were similar to non-hospice-using cancer patients at the end of life (Hogan et al., 2000).

Pritchard and colleagues reported on regional variation in where patients died and found that the availability of Medicare hospice services affected the likelihood of dying at home (Pritchard et al., 1998). However, the overwhelming predictor was regional hospital bed supply. The amount of regional variation is substantial: between 14 percent and 49 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in different areas use intensive care units (ICUs) in the last six months of life, and the aggregate Medicare costs of that time are between $6,200 and $18,000 (Dartmouth, 1999). Work on regional variation illustrates the complex relationship of location, costs, service supply, and patient preferences. Higher bed supply is almost always a strong predictor of higher costs and more hospitalization, but it is not at all clear whether there is an optimum rate or whether increased availability of other services is necessary to support low rates of hospital supply.

While patients with cancer wish to die at home among familiar surroundings, labeling this as cost-effective (or cost-saving) may be premature, given the complex nature of the disease, technological advances, family resources. Very little research has described the costs to caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. One study of cancer patients who were undergoing active treatment reported that the average cancer home care costs for a three-month period were not much lower than the costs of nursing home care (Stommel et al., 1993).

Problem of Varying Lengths of Life

Virtually our entire slim database on costs implicitly turns on a problematic assumption that the time to death is not affected by the treatments given or the choices of patients and others. On the few occasions when a researcher aimed to learn whether an intervention could be justified in terms of lengthening life, a rough estimate of cost per year of life might be made. However, if good palliative care extends life by a few months or if nursing home placement shortens life, these effects have not been assessed. Thus, since patients’ length of life varies substantially anyway, it would be hard to notice whether interventions or patterns of care altered survival time by a few months. Yet, this effect could be substantial in financial terms. The last few weeks or months characteristically have the highest costs. If some patterns drag out this time and others foreshorten it, analyses that do not take this into account could yield seriously misleading assessments of costs. Once the patient is very sick, the most substantial contributor to lifetime costs is survival time. No method corrects costs per unit time for changes in the numbers of units of time. Indeed, policymakers would reasonably be concerned about whether to focus on lifetime costs or costs for each unit of time.

REFORMS IN FINANCING ARRANGEMENTS TO IMPROVE END-OF-LIFE CARE

End-of-life care is unavoidably expensive, largely because people are very sick, but also because prognoses are ordinarily ambiguous until very close to death. One could certainly aim reforms at using existing funds more cleverly, but one cannot hope to reduce the costs of care substantially for those who are living with serious disability from cancer or for treatments that might still give the patient a chance to live longer or better.

Medicare and other insurers do not often cover the services most needed, and the services best covered may well be overused. While some surgeries or invasive procedures still offer benefits to patients coming to the end of life, the balance of burdens and benefits makes it much less likely that these treatments still offer net benefits. Instead, the kinds of things that ordinarily have few side effects and substantial benefits are prescription medications (such as opioid analgesics), family support, and respite care. These either are not covered at all or are covered only under unusual circumstances. Some services, such as psychosocial support, family and patient education, and advance care planning, are partly covered if provided by a qualified provider and supported by adequate documentation, but the time and effort needed to meet requirements may exceed the reimbursement.

Once a person has advanced cancer, many of the problems that he or she will face can be anticipated, and plans can be put in place to provide thoughtfully designed responses. This anticipation of future possibilities and implementation of customized plans has come to be called “advance care planning,” and it functions to avoid emergency responses that no longer serve the patient well, such as resuscitation at the end of life. Advance care planning also functions to implement the patient’s and family’s perspective on the merits of various courses of care.

Care patterns that routinely transfer patients from one provider of care to another do not generally focus upon advance care planning. Making plans requires envisioning the patient’s situation comprehensively, effectively communicating about the situation and its possible treatments with patient and family, and having the capability to implement plans where the patient lives (including home, assisted living, or nursing home). The usual physician in an office or hospital has few incentives to take the time and endure the problems of doing this, since it seems to be enough to implement the recommended treatment protocols or address the patient’s current problem.

Indeed, the interfaces between provider types cause many “built-in” disruptions in care. Some physicians who work in hospitals do not even register to write prescriptions for controlled drugs for patients at home. When their patients leave the hospital, they have to get opioid medications from another physician, leading to a delay, which invites recurrence of pain. Often, the physician in the nursing home simply prefers different medications from the physician in the hospital, thus guaranteeing a period of risk from overdosing or underdosing with each transfer. Many provider organizations, as a matter of policy, do not trust the decisions made in other settings to forgo resuscitation, artificial feeding, or other important treatments. Thus, when the patient is transferred, these plans have to be reestablished. If communication is difficult or the situation is deteriorating rapidly, repeating the discussion of plans may not be done in time. Again, the patient’s plans end up not being implemented.

In short, continuity matters to the seriously ill and dying, but the payment arrangements do not generally support this good aim. Physicians actually are paid better for having many initial examinations rather than for continuity. Hospices are barred from providing care to patients who are not yet eligible for hospice. Indeed, hospices and home care agencies cannot arrange integrated services with one another, even though such services might insulate patients from the problems of transfers. Once enrolled in hospice (or PACE, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly), patients enjoy continuity and comprehensiveness, and these programs have nearly universal advance care planning and the lowest rates of transfer in health care. Transfers in these programs arise almost entirely from patient

choice or from the forced discharge of hospice patients who stabilize and cannot be certified as continuing to have less than six months to live. Various options could be made available to rearrange payment and coverage to encourage continuity.

With continuity comes a drive for comprehensiveness. Issues such as family support, bereavement counseling, and housing are unavoidable when care providers stay with the patient through whatever comes up. More continuity and comprehensiveness may well encourage innovations such as paying family caregivers (as much of Europe already does), providing respite care, developing supported housing, and ensuring that medications are available.

Modifications to hospice seem to be an obvious target for improving end-of-life care for patients with cancer (President’s Cancer Panel, 1999). Hospice could be made available on the basis of the extent of illness or disability and then be lifelong, rather than requiring a confident prediction of death within six months. Hospice expertise could be made available to patients who are not eligible for direct services by allowing consultation by the hospice team. It makes sense for hospice team members to become known to patients with eventually fatal malignancies during the course of their illness, rather than just at the very end of life. In short, enrollment into hospice should be a less dramatic change and a more expected and integrated transition. Hospice programs could be paid somewhat more for the first day or two and the last day or two (and perhaps less for longer-term stays). Payments for costly treatments should be considered on their own merits. If evidence shows that the costs are worth it in the community’s judgment, then those interventions that cannot generally be provided within the hospice capitation should be paid separately for small programs or should be folded into the overall capitation rate for large programs.

How could society move to make these reforms? We need an era of innovation and evaluation, aiming to learn how to engineer our care system to provide reliably competent, comprehensive services from the time of onset of serious illness through to death.

In doing this, society will need more reliable data on the relevant populations. The available research has usually measured costs in a referral clinic serving a population that is more than a decade younger than the average of those who face the problem. Policymakers need data about the effects and costs of various treatment strategies and approaches to organizing care delivery, in samples that represent the entire population at risk. This information requires developing new methods and substantial commitments.

Until now, society has focused mainly on premature deaths and disability. Having won many of these battles, most people now get the opportunity to live long and die of degenerative conditions such as cancer. As a

society, we need to learn new framing, new approaches, and new ways of paying for the care that people need at the end of life. It can be done, and done within just a few years, if we set about the job now.

POSSIBLE STRATEGIES TO IMPROVE FINANCING FOR CARE OF PATIENTS COMING TO THE END OF LIFE WITH CANCER

Reshaping the financing of end-of-life care for those with cancer requires attention to three elements: serviceable methods, adequate description and monitoring, and innovation with evaluation. Many organizations bear responsibility for addressing these needs, some of which are noted (in parentheses) in the discussion that follows.

Methods Development Priorities

-

Metrics for costs and effects (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA], National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], MedPAC, Department of Veterans Affairs [VA])

-

Benchmarks—what quality can real systems yield? (AHRQ, Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA], HCFA, VA)

-

Developing models to correct for nongeneralizable populations (AHRQ, HCFA)

-

Efficient methods to monitor population experience with end-of-life care in cancer, measuring outcomes and processes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], AHRQ).

-

Efficient reporting and analysis of costs, in aggregate and to various payers (HCFA, MedPAC, AHRQ)

-

Exploration of the relationship between costs and life span, and development of language and methods to correct for varying life span in assessment of cost (National Institutes of Health [NIH], AHRQ, VA)

Descriptive Data Priorities

-

Developing surveillance methods to monitor trends and comparisons among populations by age, race, diagnosis, and geographic locality (CDC, states)

-

Describing service use (including hospice) by outcomes, variations, and comparisons across geographical areas (HCFA, AHRQ)

-

Assessing the costs and benefits of interventions in generalizable populations (NIH, AHRQ)

Innovation and Evaluation

We urgently need a period of innovation, with thoughtful evaluation and learning, in order to shape the care system and payment arrangements so they will better serve cancer patients coming to the end of life. Here, a list of possibilities is provided. Many agencies and programs should take part, but it seems likely that NCI, AHRQ, HRSA, HCFA, and the VA should be in the lead. In each case, an innovation is listed, but it is essential that each innovation be evaluated and that insights be gained from the trial. These examples are meant to be illustrative, not comprehensive or sufficient. The important conclusion is that innovations such as these should be tried out, in substantial numbers, and soon.

PRESCRIPTION DRUG COVERAGE

-

If Medicare covers medications, examine effects on end-of-life care.

-

If there is a formulary or purchasing cooperative, evaluate comprehensiveness and efficiency of symptom treatments.

-

If Medicare does not cover medications generally, experiment with coverage for symptoms only.

HOSPICE

-

Change enrollment criterion from prognosis to severity (or extent) of illness and allow continuous enrollment from onset of a certain severity to the end of life.

-

Pay more for the first day or two and the last day or two.

-

Carve out certain high-cost treatments or “pay down” their cost to the program to a reasonable cost share.

-

Allow the hospice team to consult on nonhospice patients.

-

Increase the daily rate, tailored to specific diagnoses.

-

Encourage “bridge” and “graduate” programs, with funding beyond home care.

-

Require coverage of hospice in Medicaid.

-

Reward physicians (e.g., with better administrative arrangements) for signing up patients on hospice.

NURSING FACILITY OR LONG-TERM CARE

-

Integrate hospice care and nursing home care at a fair rate of pay.

-

Develop regional guidelines on management of common symptoms and advance care planning to ease transfers.

-

Make key consultations for difficult symptoms readily available on-site.

-

Provide incentives so that most residents can live to the end of life in their residence.

-

Evaluate high rates of hospital transfer as evidence of potentially avoidable adverse events.

HOME CARE

-

Modify home care eligibility to ease the homebound requirement.

-

Ensure quick availability of key consultations for difficult symptoms arising in a home care patient.

-

Establish rate and enrollment criteria encouraging “bridge programs” that are integrated with hospice.

-

Try out integrated home-hospice-institutional care programs (PACE, MediCaring).

-

Encourage geographic concentration by programs.

CAPITATED PLANS

-

In PACE, the payment rate for Medicare is set at the nursing home rate and Medicaid makes up the rest. The Medicare rate is almost certainly too low for cancer patients, forcing Medicaid to make up more of the overall rate and thereby making PACE care of cancer patients unattractive for the states. PACE’s Medicare payments could mirror the risk adjustment rates, once those are set.

-

Make risk adjustment plans cover end-of-life care (e.g., for patients not likely to live into next year; for patients cared for mainly out of hospital).

-

Purchase on quality of end-of-life care.

-

Adjust the risk adjustment plan to improve end-of-life care.

FEE FOR SERVICE

-

Reduce the differential between procedure and counseling payments.

-

Designate palliative care specialization, to avoid problems with concurrent care.

-

Provide incentives for advance planning before repeat hospitalization.

-

Provide incentives for coordinated care before repeat hospitalizations.

-

Provide incentives for services in centers of proven quality in end-of-life care.

FOR FAMILY CAREGIVERS

-

Pay family caregivers a discounted rate for their services (e.g., half the going rate for paid services).

-

Provide health insurance for full-time family caregivers who have no other source of insurance.

-

Provide payment for respite help, either in-home or in-facility.

-

Provide more paid help at home, including in PACE and hospice.

FOR HIGH-COST PALLIATIVE CARE

-

Require accounting of the aggregate costs and benefits of costly interventions in realistically representative populations.

-

Develop a regional or national review process that can limit coverage for particular interventions to particular kinds of patients or can keep a particular treatment from being covered at all.

-

Monitor effects of high-cost interventions, especially effects on availability of aide care and psychosocial services.

FOR CAPACITY BUILDING AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

-

Involve HRSA in addressing the concerns of the population needing end-of-life care, including cancer. This would bring to bear the skills and attention of professional educators, manpower experts, health services delivery managers, and innovators and evaluators.

-

Tie Medicare payments to quality (e.g., the upcoming effort to tie managed care payments to heart failure performance standards).

-

Build culture of quality improvement; pay for the work.

-

Consider the role of routine autopsy.

CONCLUSION

The quality, reliability, and comprehensiveness of end-of-life care are important to cancer patients and their families. Some of the current shortcomings arise from financing and regulations; others, from habit patterns. Enduring reforms must be guided by descriptive and evaluative data, which are not available. This shortcoming should be corrected quickly. We need a decade of vigorous innovation and evaluation, learning how to improve policies. As we settle upon desirable changes, we will also need to forge the political will for reform.

REFERENCES

Agra Y, Sacristan A, Gonzalez M, Ferrari M, Portugues A, Calvo MJ. Efficacy of senna versus lactulose in terminal cancer patients treated with opioids. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 1998; 15:1–7.

American Cancer Society. 2000. http://www.cancer.org/statistics/index.html

Beemstrober PM, de Koning HJ, Birnie E, et al. Advanced prostate cancer: course, care and cost complications. Prostate 1999; 40:97–104.

Bennett CL, Matchar D, McCrory D, McLeod DG, Crawford ED, Hillner BE. Cost-effective models for flutamide for prostate carcinoma patients: are they helpful to policy makers? Cancer 1996; 77:1854–1861.

Brooks CH. A comparative analysis of Medicare home care cost savings for the terminally ill. Home Health Care Services Quarterly 1989a; 10:79–96.

Brooks CH. Cost differences between hospice and nonhospice care. A comparison of insurer payments and provider charges. Eval Health Prof 1989b; 12:159–178.

Brooks CH, Smyth-Staruch K. Hospice home care cost savings to third-party insurers. Medical Care 1984; 22:691–703.

Brown ML, Riley GF, Potosky AL, Etzioni RD. Obtaining long-term disease specific costs of care: application to Medicare enrollees diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Medical Care 1999; 37:1249–1259.

Bruera E, Pruvost M, Schoeller T, Montejo G, Watanabe S. Proctoclysis for hydration of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Pain Symptom Management 1998; 15:216–219.

Buroker TR, O’Connell MJ, Wieand HS, Krook JE, Gerstner JB, Mailliard JA, et al. Randomized comparison of two schedules of fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer [see comments]. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1994; 12:14– 20.

Christakis NA, Escarce JJ. Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. New England Journal of Medicine 1996; 338:172–178.

Commonwealth Fund. 1998. Improving Coverage for Low-Income Medicare Beneficiaries. New York: Commonwealth Fund.

Cunningham D. Mature results from three large controlled studies with raltitrexed (‘Tomudex’). British Journal of Cancer 1998; 77(Suppl)2:15–21.

Cvetkovski B, Gerdes H, Kurtz RC. Outpatient therapeutic ERCP with endobiliary stent placement for malignant common bile duct obstruction. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 1999; 50:63–66.

Dartmouth Medical School, Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences. 1999. The Quality of Medical Care in the United States: A Report on the Medicare Program. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in the United States, 1999, Wennberg JE, Cooper MM., eds. Chicago: AHA Press.

Desch CE, Hillner BE, Smith TJ. Economic considerations in the care of lung cancer patients. Current Opinion in Oncology 1996; 8:126–132.

Emanuel EJ. Cost savings at the end of life. What do the data show? [see comments]. Journal of the American Medical Association 1996; 275:1907–1914.

Escalante CP, Martin CG, Elting LS, Cantor SB, Harle TS, Price KJ, et al. Dyspnea in cancer patients. Etiology, resource utilization, and survival-implications in a managed care world. Cancer 1996; 1978:1314–1319.

Experton B, Ozminkowski RJ, Pearlman DN. How does managed care manage the frail elderly? The case of hospital readmissions in fee-for-service versus HMO systems. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1999; 16(3):163–172.

Ferris FD, Wodinsky HB, Kerr IG, Sone M, Hume S, Coons C. A cost-minimization study of cancer patients requiring a narcotic infusion in hospital and at home. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1991; 44:313–327.

Fox E, Landrum McNiff, Zhong Z, et al. Evaluation of prognostic criteria for determining hospice eligibility in patients with advanced lung, heart, or liver disease. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association 1999; 282(17):1638–1645.

Glimelius B, Hoffman K, Graf W, Haglund U, Nyren O, Pahlman L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of palliative chemotherapy in advanced gastrointestinal cancer [see comments]. Annals of Oncology 1995; 6:267–274.

Goodwin PJ, Shepherd FA. Economic issues in lung cancer: a review. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1998; 16:3900–3912.

Hillner BE, Weeks JC, Desch CE, Smith TJ. Pamidronate in prevention of bone complications in metastatic breast cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2000; 18:72–79.

Hogan C, Lynn J, Gabel J, Lunney J, O’Mara A, Wilkinson A. 2000. A Statistical Profile of Decedents in the Medicare Program. Washington, D.C.: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission.

Iezzoni LI. The risk of adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association 1997; 278(19):1600–1607.

Ingham JM. 1998. The epidemiology of cancer at the end stage of life. In Principles and Practice of Supportive Oncology, Berger A, Portenoy R, Weissman DE, eds. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1997. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Field MJ, Cassel CK, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1999. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Hewitt M, Simone JV, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Integrating economic analysis into cancer clinical trials: the National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Economics Workbook. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monograph 1998; 1924:1–28.

Kaskarelis IS, Minardos IA, Abatzis PP, Malagari KS, Vrachliotis TG, Natsika MK, et al. Percutaneous metallic self-expandable endoprostheses in biliary obstruction caused by metastatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 1996; 43:785–791.

Kidder D. The effects of hospice coverage on Medicare expenditures. Health Services Research 1992; 27:195–217.

Kosary C L, Ries LAG, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Harras A, Edwards BK. 2000. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1992: Tables and graphs, NIH Pub. No. 96–2789. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Lewin-VHI, Inc. 1995. An Analysis of the Cost Savings of the Medicare Hospice Benefit. Commissioned by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Lubitz JD, Riley GF. Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. New England Journal of Medicine 1993; 328:1092–1096.

Lynn J, Harrell F, Cohn F, et al. Prognoses of seriously ill hospitalized patients on the days before death: implications for patient care and public policy. New Horizons 1997; 5(1): 56–61.

McEwan AJ, Amyotte GA, McGowan DG, MacGillivray JA, Porter AT. A retrospective analysis of the cost effectiveness of treatment with Metastron (89Sr-chloride) in patients with prostate cancer metastatic to bone. Nucl Med Commun 1994; 15:499–504.

Mor V, Masterson-Allen S. A comparison of hospice vs conventional care of the terminally ill cancer patient. Oncology 1990; 4:85–91.

National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. 2001. http://www.NHPCO.org/facts.htm

Neymark N, Adriaenssen I. The costs of managing patients with advanced colorectal cancer in 10 different European centres. European Journal of Cancer 1999; 35:1789–1795.

Peters WR, Dansey RD, Klein JL, Baynes RD. High-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation in the treatment of breast cancer. Oncologist 2000; 5:1– 13.

Polednak Ap, Shevchenko Ip. Hospital charges for terminal care of cancer patients dying before age 65. Journal of Health Care Finance 1998; 25(1)26–34.

President’s Cancer Panel. 1998. Cancer Care Issues in the United States: Quality of Care, Quality of Life. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 1999. (http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/ADVISORY/pcp/reports/index.htm)

Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Risks and Outcomes of Treatment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1998; 46(10):1242–1250.

Ramesh PR, Kumar KS, Rajagopal MR, Balachandran P, Warrier PK. Managing morphine-induced constipation: a controlled comparison of an Ayurvedic formulation and senna. Journal of Pain, Symptom Management 1998; 16:240–244.

Recchia F, Nuzzo A, Lalli A, Lombardo M, Di Lullo L, Fabiani F, et al. Randomized trial of 5-fluorouracil and high-dose folinic acid with or without alpha-2B interferon in advanced colorectal cancer. American Journal of Clinical Oncology 1996; 19:301–304.

Riley GF, Potosky AL, Lubitz JD, et al. Medicare payments from diagnosis to death for elderly cancer patients by stage at diagnosis. Medical Care 1995; 33(8):828–841.

Ron IG, Lotan A, Inbar MJ, Chaitchik S. Advanced colorectal carcinoma: redefining the role of oral ftorafur. Anticancer Drugs 1996; 7:649–654.

Ross P, Heron J, Cunningham D. Cost of treating advanced colorectal cancer: a retrospective comparison of treatment regimens [see comments]. European Journl of Cancer 1996; 32A (Suppl)5:S13–S17.

Scheidbach H, Horbach T, Groitl H, Hohenberger W. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy/ jejunostomy (PEG/PEJ) for decompression in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Initial experience with palliative treatment of gastrointestinal obstruction in terminally ill patients with advanced carcinomas. Surgical Endoscopy 1999; 13:1103–1105.

Seamans DP, Wong GY, Wilson JL. Interventional pain therapy for intractable abdominal cancer pain. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2000; 18:1598–1600.

Shah Syed GM, Maken RN, Muzzaffar N, Shah MA, Rana F. Effective and economical option for pain palliation in prostate cancer with skeletal metastases: 32P therapy revisited. NuclMedCommun 1999; 20:697–702.

Smith TJ, Hillner BE, Desch CE. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of cancer treatment: rational allocation of resources based on decision analysis [see comments]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1993; 85:1460–1474.

Stommel M, Given CW, Given BA. The cost of cancer home care to families. Cancer 1993; 71: 1867–1874.

Torfs K, Pocceschi S. A retrospective study of resource utilisation in the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer in Europe. European Journal of Cancer 1996; 32A(Suppl)5:S28– 31.

Ulrich-Pur H, Kornek GV, Raderer M, Haider K, Kwasny W, Depisch D, Greul R, Schneeweiss B, Krauss G, Funovics J, Scheithauer W. A phase II trial of biweekly high dose gemcitabine for patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2000; 88(11): 2505–2511.

Vladeck BC. The problem isn’t payment: Medicare and the reform of end-of-life care. Generations 1999; 21:52–57.