OBSERVATIONS ON THE PRESIDENT’S FY 2002 FEDERAL SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY BUDGET

ALLOCATING FUNDS FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

The Federal Science and Technology Budget

Since World War II, the science and engineering enterprise in the United States has produced enormous benefits for the nation’s economy, defense, health, and social well being. Numerous reports over the past decade have documented this key role for science and engineering and have argued persuasively that advancing science and technology in the future is key to sustaining our nation’s future health, security, and prosperity.7

In Science, Technology and the Federal Government: National Goals for a New Era (1993), Allocating Federal Funds for Science and Technology (1995), and subsequent reports in this series, the National Academies have called for the nation to continue to invest in science and technology at a level that allows the United States to sustain preeminence in a select number of fields and to perform at a world-class level in all other fields of science and technology. The federal government plays a critical role in funding the science and engineering enterprise in the United States. Since 1980, industry’s share of R&D has grown from one-half to two-thirds, but industry spent just 9 percent of its R&D funds in 1999 on basic research, while it spent 20 percent on applied research and 71 percent on development.8 Thus, in 1999, the federal government provided 50 percent of funding for basic research, compared to 33 percent from industry. Accordingly, the federal government remains a critical source of funds for research that creates new knowledge and enabling technologies and provides the underpinning for the applications fueling a growing high-tech economy.

Given the continuing role of federal funding in meeting our nation’s goals for advancing science and technology, Allocating Federal Funds specifically recommended that the President and Congress should ensure that federal spending on science and technology is both sufficient and targeted. The report urged that the President, with the advice of the directors of the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of Science and Technology Policy, develop a coherent and comprehensive process for deciding how federal funds should be invested in science and technology. The report also urged that the Administration present to Congress a federal science and technology (FS&T) budget, defined as the federal investment leading to the “creation of new knowledge and enabling technologies.”9 The FS&T budget should, in the aggregate, be sufficient to both meet agency missions and sustain the nation’s leadership role in science and technology.

Tabulating the FS&T Budget

The FS&T budget has been defined by the Academies as federal R&D spending that creates new knowledge and enabling technologies. As a practical matter, FS&T has been calculated by taking as FS&T the R&D budget for most federal agencies. The Department of Defense has more precisely identified that part of its Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) that is explicitly an investment in science and technology, so the Academies method has included for DOD its spending on basic research (6.1), applied research (6.2), and advanced technology (6.3). The Academies method for calculating FS&T has excluded R&D in programs that clearly involve testing, evaluation, or other activities not primarily devoted to the creation of new knowledge or technologies: the Demonstration and Validation (6.4), Engineering and Manufacturing Development (6.5), RDT&E Management Support (6.6), and Operational Systems Development (6.7) programs in the Department of Defense (DOD) budget, as well as the Naval Reactor Program in the Department of Energy (DOE).

The National Academies’ Committee on Science Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP) has issued three annual reports providing observations on the Administration’s proposed FS&T spending in fiscal years 1999, 2000, and 2001. These reports have provided the Administration, Congressional appropriators, and the science policy community with data on that part of the R&D budget that focuses on science and technology. During that same period, the Clinton Administration moved toward the FS&T concept by identifying, in addition to the R&D budget, the federal investment in an array of major science and technology programs. In its first iteration in fiscal year 1999, this crosscut was presented as the Research Fund for America (RFFA), which focused exclusively on civilian research programs. Over the next two budget cycles, this crosscut was renamed the 21st Century Research Fund and expanded to include basic research (6.1) and applied research (6.2) in the Defense budget.

The new Administration’s fiscal year 2002 budget proposal represents an important opportunity for institutionalizing an annual, concerted focus on the nation’s plans for investing in science and technology. In its budget proposal, the Bush Administration has continued the practice of including a science and technology crosscut in its budget proposal, modifying the 21st Century Research Fund further and renaming it the “Federal Science and Technology Budget.” In doing so, moreover, the Bush Administration cited the recommendation in Allocating Federal Funds for highlighting “more consistently and accurately activities central to the creation of new knowledge and technologies” as the justification for including the FS&T budget in its budget proposal.10

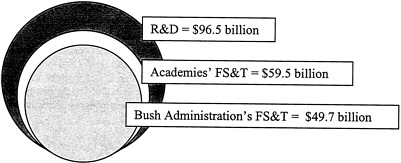

Figure 1 and Table 1 compare the National Academies’ tabulation of the FS&T Budget ($59.5 billion) with both the Administration’s method of tabulating FS&T ($49.7 billion) and the traditional R&D spending crosscut ($96.5 billion) in the President’s FY 2002 budget proposal. As the figure and table show, the Administration’s FS&T budget tabulation differs from the Academies’ FS&T tabulation by about $10 billion. The inclusion in the National Academies’ FS&T budget of the DOD advanced technology (6.3) budget ($4.1 billion), the DOE Atomic Weapons Activities ($2.9 billion), and NASA Human Space Flight R&D ($2.8 billion) accounts

FIGURE 1. Proposed FY 2002 federal spending for R&D and FS&T

for almost all of the numerical difference between the Academies’ and Administration’s FS&T calculations. In addition, the Academies’ FS&T budget includes R&D at all federal agencies, while the Administration’s FS&T focuses on the 12 largest R&D agencies.

In addition to differences in the programs included in the tabulation, there are other differences in the ways the Academies and the Administration approach the budgets of the 12 largest R&D agencies. The Academies have constructed the FS&T budget by including only investments that each of these agencies estimates as R&D (excluding DOD 6.4–6.7 and DOE Naval Reactors R&D). The Administration, however, includes the entire budget for each of the major science and technology programs it highlights, not just their R&D components. For example, FS&T at NSF under the Academies’ tabulation is $3.226 billion. The Administration, however, includes salaries, the Inspector General’s office, and education and human resources programs at NSF, resulting in FS&T for that agency of $4.472 billion. Similarly, the entire budgets are also included for NIH, DOE’s Energy and Science Programs, the National Institute for Standards and Technology, and the U.S. Geological Survey. The Administration believes the inclusion of the full budget, including salaries for staff who make funding and other programmatic decisions for these agencies and programs, provides a more accurate measure of the nation’s expenditures on science and technology.

For four years, the National Academies and the Administrations of both President Clinton and President Bush have tracked federal spending on science and technology. The philosophical underpinnings and methods of tabulations used by the Academies and the two Administrations have been converging over time. It is in the interest of both sound science policy and an effective budgetary process that the science and engineering community and the Administration adopt one method of tabulating the Federal Science and Technology Budget.

There is considerable merit to the method for tabulating the federal investment in science and technology developed over the past several years by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget and included in the Bush Administration’s FY 2002 budget request. First, the practice of

including the full budget for a program highlights the importance of program management and salary costs that are critical to operating science and technology programs but are not always included in agency estimates of R&D. Incorporating the full budget of an agency, such as NSF, means that its science and mathematics education programs, arguably key investments in science and technology that are not counted as R&D, are included in calculating the federal investment in S&T. Second, the Administration’s method of including the full budget for each science and technology program allows each item and the entire FS&T budget to be tracked through the appropriations process, a feature that the R&D budget and the Academies’ FS&T budget lack. As a tool for affecting the Congressional appropriations process, therefore, the Administration’s approach has considerable advantages.

Given its benefits, the Administration’s approach to tabulating the Federal Science and Technology Budget is the preferred method for tracking FS&T. The Administration should continue to tabulate this budget in future years and the science and engineering community should likewise focus its observations on this tabulation. As the RFFA evolved into the 21st Century Research Fund and now the Federal Science and Technology Budget, the Clinton and Bush Administrations have made changes from year-to-year in what is included in the Administration’s tabulation. The Administration should continue to refine its tabulation of the FS&T budget further to ensure that all federal programs that create new knowledge and technologies and can be tracked through the appropriations process are included. Over time, though, a stable definition of the FS&T budget category will be most useful. OMB, in consultation with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, should prepare a document that provides such a definition and the rationale underlying it.

THE PRESIDENT’S FY 2002 FS&T BUDGET

The President’s FY 2002 Proposal

The nation should continue to invest in science and technology at a level that allows the United States to meet agency missions, address important national priorities, and sustain our global leadership in science and technology. Previous volumes in this series of annual Observations have expressed concern about our ability to meet these goals, given the overall size of the federal investment in S&T and differing rates of growth in agency S&T budgets and their impact on funding across the range of science and engineering disciplines.

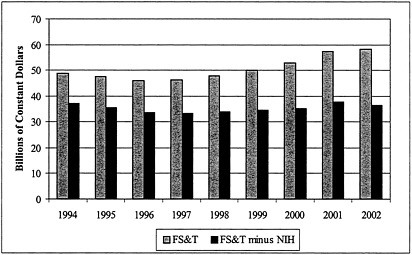

As seen in Table 2 and Figure 2, the overall size of the FS&T budget decreased annually in constant dollars from FY 1994 to FY 1996, before turning up in FY 1997.11 The Academies method of tabulating FS&T shows that the FS&T budget only surpassed its FY 1994 level in FY 1999. Increases since then have generated an overall increase of 17.3 percent in constant dollars from FY 1994 to FY 2001. The increase of 8.5 percent in FS&T from FY 2000 to FY 2001, however, comprises more than half of the overall increase in FS&T since FY 1994.12

FIGURE 2. Federal science and technology budget and federal science and technology budget excluding NIH FS&T, billions of constant FY 2001 dollars, 1994–2002

Note: FY 1994–2000 is actual Congressional appropriations; FY 2001 is estimated Congressional appropriations; FY 2002 is proposed spending under the Presidents FY 2002 budget proposal. Figure is based on data in Table 3, which uses the Academies’ method for tabulating FS&T.

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, FY 2002: Analytical Perspectives; AAAS, AAAS Report XXVI: Research and Development, Fiscal Year 2002, (Washington, D.C.: AAAS, 2001), Table I-16. FS&T figures for 1994–1999 carried forward from Observations on the President’s FY 2001 Federal Science and Technology Budget.

The President’s FY 2002 budget proposal returns to a pattern of slower FS&T growth.13 As seen in Table 3, the Academies’ method of tabulating FS&T shows an increase of $950 million, or 1.7 percent in constant dollars from FY 2001 to FY 2002. This compares to an average annual increase of 4.5 percent from FY 1996 to FY 2001. This increase is also less than the overall increase in discretionary spending requested by the Bush Administration (4.0 percent in current dollars; 1.9 percent in constant dollars). If one uses the Administration’s tabulation of FS&T, that budget fares slightly better than discretionary spending as a whole, but the proposed 3.0 percent increase in FS&T in constant dollars is smaller than the 9.2 percent increase enacted last year, as seen in Table 4.

The overall increase in FS&T since FY 1994, as tabulated using the Academies’ method, masks important differences in rates of growth for FS&T among agencies. While FS&T in the NIH budget increased 88.2 percent in constant dollars from FY 1994 to FY 2001, FS&T at all other agencies increased only 1.7 percent during the same period. Indeed, as seen in Figure 2 and

Table 2, the FS&T budget excluding NIH declined after FY 1994 and only surpassed the FY 1994 level in FY 2001.

The President’s FY 2002 budget proposal continues a pattern of substantially differing growth rates for the various science and technology programs in the federal government. In the Academies FS&T tabulation as seen in Table 3,14 FS&T in NIH would increase more than $2.2 billion, or 11.3 percent in constant dollars, from FY 2001 to FY 2002. FS&T without NIH would decrease by 3.4 percent from FY 2001 to FY 2002 and would, in constant dollars, return to a level below that of FY 1994. The only other major Department with a substantial increase would be the Department of Transportation (DOT), whose FS&T budget benefits from a dedicated source of revenue in the Federal Highway Trust Fund and would increase 4.6 percent in constant dollars. FS&T spending in all other departments and agencies with major FS&T programs would be flat or decrease in constant dollars from FY 2001 to FY 2002. FS&T at the National Science Foundation, which increased 9.6 percent from FY 2000 to FY 2001 in constant dollars, would decrease by 3.4 percent from FY 2001 to FY 2002. FS&T at NASA would decrease 1.7 percent; at DOE by 6.8 percent; at Commerce and Agriculture by 9.5 and 9.9 percent respectively.15

The FS&T Budget and National Goals

The Administration developed its FY 2002 budget so that it would address key national goals articulated by the President during last fall’s presidential campaign: enacting a $1.6 trillion tax cut,16 holding discretionary spending to an overall increase of four percent, and funding Administration initiatives in education, biomedical research, and defense. The Administration’s FY 2002 Federal Science and Technology Budget proposal is a derivative of these fiscal and policy objectives. In reviewing the President’s proposed FS&T budget, Congressional appropriators should bear in mind the range of our national goals in defense, energy security, environmental protection, health, the economy and other areas and ask whether the Administration’s proposed investment in science and technology research is sufficient to address these goals in the short run and help achieve them in the long run.

First, the proposal for a large increase in funding for NIH to keep it on track for doubling its budget by FY 2003 was an important goal articulated by the President in the campaign and is now the centerpiece of the Administration’s proposal for science and technology. The Administration sees the increase of $2.2 billion, in constant dollars, in FS&T at NIH as an important step in improving the health of the nation’s citizens.17 NIH is a potent contributor to medical innovation and the growth of biotechnology and, thus, is one of several important means for addressing the most significant health problems of the U.S. population.18

It is important for appropriators to understand, however, that the path of discovery from original research to application is highly uncertain and technological advances, whether in biomedical applications or other technology areas, can result from investments in fundamental research in a variety of areas. Federal funds that supported the “War on Cancer,” for example, led to dramatic gains in AIDS research, including identification of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and AZT, as well as critical new breakthroughs in molecular biology.19 At the same time, many of the improvements in medical technology seen in the past decades are the result of the advancement of knowledge that comes from research outside the life sciences in such fields as physics or engineering and often funded by agencies other than NIH. Examples would include magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and miniaturization in arthroscopic surgery. Similarly, funding for social science research has contributed to an understanding of how modifying individual behavior or social structures can impact both individual health and health care delivery.

Second, the constraints imposed on discretionary spending in the President’s proposal, especially once the Administration’s initiatives in education, biomedical research, and defense are funded, limit FS&T in agencies other than NIH to flat budgets at best, and large decreases at worst. This raises concerns about whether proposed FS&T spending in these agencies is sufficient for addressing national needs beyond improving the health of Americans.

The Administration argues that most FS&T programs are financially sound since many FS&T programs enjoyed unusually large increases in FY 2001. Even many agencies with decreases from FY 2001 to FY 2002, their argument continues, would have substantial average annual budgetary increases from FY 2000 to FY 2002. The Administration notes, for example, that the NSF budget would be 15 percent larger, in current dollars, in FY 2002 compared with FY 2000.20 This would be an increase of 10 percent in constant dollars over the two-year period, even with a decrease of 0.8 percent from FY 2001 to FY 2002.

However, the Administration’s budget, developed in a time of transition from one Administration to another and from the presidential campaign to governance, may require adjustments to bring proposed FS&T spending more closely in line with national goals in such diverse areas as national security, energy, environmental protection, and excellence in science.

Since submitting its budget proposal, the Administration has undertaken program and policy reviews in areas in which science and technology play a key role in addressing national goals, but FS&T is either level funded or slated for reductions in FY 2002. The Administration is conducting a strategic review of the Department of Defense and may provide a new budget proposal for DOD FS&T, as well as for other DOD spending, that may bring spending in this area more in line with national goals for defense once the review is completed. The Administration has also reviewed, since submitting its budget proposal, our national energy goals and policies. Among the Administration’s energy proposals, for example, is increased use of nuclear energy to

generate electric power, though nuclear energy R&D was slated for a substantial budget reduction in the Administration’s budget proposal. This policy shift suggests that Congress should review the Administration’s proposed spending on the range of science and technology programs from nuclear energy R&D to sustainable energy R&D at the Department of Energy to determine if it is sufficient for both meeting national goals for energy security and the Administration’s energy program. Similarly, the Administration has begun a re-examination of our nation’s policies with regard to global climate change. Our ability to understand the phenomenon of global climate change is critical to forming policy in this area. Congress should fund scientific research at a level that would allow it to provide that understanding at this time of policy review and reformulation.21

Science and technology investments across the life sciences, physical sciences, and engineering have enabled much of the innovation that has been the source of our recent, sustained economic growth and are, therefore, critical to also addressing national economic goals. Research has continually led to promising commercial opportunities throughout the last 50 years. One of the key reasons for sustaining global leadership in science and technology is to generate further such opportunities and sustain economic growth and global competitiveness as well as meet our goals in national security, energy, the environment, and health.

Since we cannot predict which investments made today in science and technology will result in the key technologies and innovations of the future, this suggests a pattern of broadly supporting science and technology across fields, particularly in the area of basic research where the federal government plays a central funding role. In this regard, differing growth rates in FS&T investments across agencies and fields of science and engineering are of concern, particularly since FS&T in agencies other than NIH would fall below their FY 1994 level under the Administration’s budget proposal. The Administration and Congress should examine spending plans carefully to ensure that the federal government is investing adequately not only in biomedical research, but in other areas that generate technological innovation such as information technology research, materials science, nuclear physics, or nanoscale science and technology.

A sense of our national goals and the role that a vital science and technology enterprise can play in addressing those goals in the short run and meeting them in the long run can provide a basis for evaluating the adequacy of agency spending on science and technology research. The Administration and Congress should pay attention to the long-run health of the science and engineering enterprise and its ability to help meet our national goals, particularly as they may shift in the future. In this latter regard, much greater attention needs to be given to the impact of budget reductions in agencies other than NIH on both research and human resources across science and engineering fields.22

While there are many indicators of productivity, it is worth noting, as one example, that while federal funding for physics research at our nation’s universities decreased by more than one-fifth from 1993 to 1997, the number of article submissions by U.S. researchers to Physical