4

Financial Health of the Aerospace Industry

The aerospace industry has undergone significant restructuring in the last 20 years. A number of recent defense studies examining the implications of these changes reflect a broad consensus in the aerospace community on the characterization of the defense aerospace industrial base. The agreement on the general characterization of the aerospace environment is also reflected in highly congruent recommendations to the Department of Defense (DoD) for responding to the changes in the aerospace environment.

AEROSPACE INDUSTRY ENVIRONMENT

The aerospace industry restructuring has changed the financial metrics of the industry. In the course of this study, several studies of the defense industrial environment were conducted by other organizations (e.g., DSB, 2000b and Harbison et al., 2000). Although these studies covered the entire U.S. defense industrial base, their findings and recommendations are directly applicable to the aerospace sector.

One result of the consolidation in the defense industry has been that most defense companies now have a customer base that not only spans the entire spectrum of defense products, but also includes commercial products, which yield higher margin for less trouble. Large companies, in particular, continue to diversify to compensate for low return on investment (ROI) from government contracts, and only part of the aerospace sector produces defense products. The defense aerospace industry can be characterized as an industry in transition with many companies facing challenging problems (DSB, 2000b):

-

Because of strong competition and stringent export controls, opportunities for growth are limited.

-

Profitability, already low compared to other industries, has declined. In addition, companies that encounter problems on major programs face potentially further reduced profits.

-

Cash flow, which has traditionally been a strength of the defense industry, has declined for most companies.

-

As a result of consolidations, some companies have added to their debt, creating higher debt-equity ratios, which have resulted in lower credit ratings.

-

Market capitalization by defense companies has declined more than those for most “old-economy” companies.

-

Innovative research and development (R&D) has been reduced; funding by DoD for R&D has been flat. Funding for innovative R&D is down 50 percent from the mid-1980s and is increasingly focused on supporting ongoing programs rather than on breakthrough technologies.

-

In an era of few large production programs, the Cold War approach of “getting well on production,” that is, making up for research expenses in the production phase of a program, is no longer viable.

-

Key personnel are leaving or retiring, and retaining and recruiting new high-quality technical and management people are difficult.

In U.S. Defense Industry Under Siege: An Agenda for Change, the industry was characterized as being at a cross-roads. Although industry financial metrics have improved since the publication of that report, the underlying conditions have not changed (Harbison et al., 2000).

The underlying health of the industry is seriously suspect. As we entered the new millennium, the industry’s combined operating profitability has declined from 9.2 percent in 1996 to 7.7 percent in 1999, and the industry’s collective interest coverage ratio has fallen to 2.7 times in 1999 from 7.1 times in 1995; debt ratings have fallen to almost junk bond levels, and the industry’s market capitalization is down 33 percent from $100.1 billion in January 1997 to $66.7 billion today.

At the Defense Reform 2001 Conference organized by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, the industry environment was discussed by top industry and government officials, who called for the following changes (Velocci, 2001):

-

An immediate increase in the progress payment system from the current 75 percent, which constrains cash flow, to 85 to 90 percent;

-

Changing the export control process, which inadvertently penalizes U.S. companies and enables potential adversaries to acquire restricted military technologies from other sources;

-

Making it easier to use commercial technologies; and

-

Making it easier to retain design teams.

The studies discussed so far reflect the broad consensus of the defense industrial community. The results of the committee’s own investigations substantiated their findings and recommendations. The recommendations in these studies are summarized below:

-

The partnership between DoD and industry must be strengthened.

-

Programs and funding must be stabilized.

-

Creative incentives must be provided for the industrial base to rationalize capacity.

-

Single providers must be carefully selected and managed.

-

The spirit of innovation must be encouraged.

-

Industry concerns must be considered in the DoD acquisition process.

-

Industry metrics must be better understood.

-

Export control processes must be streamlined.

-

Human resources issues must be addressed.

INFLUENCE OF THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE ON THE AEROSPACE INDUSTRY INFRASTRUCTURE

Even though the defense industry has been dramatically consolidated since the end of the Cold War and the relationship between the industry and DoD has changed dramatically, the fundamental policies of DoD have not changed. DoD’s share in the aerospace market is shrinking as a result of an increase in nondefense sales and a decrease in DoD procurements. In 1989, DoD accounted for 51 percent of aerospace sales in the United States (see Table 4–1). Since then, DoD’s spending on aerospace items has returned to pre-Reagan levels. In 1999, DoD accounted for only 30 percent of aerospace sales (AIA, 2000, 2001a).

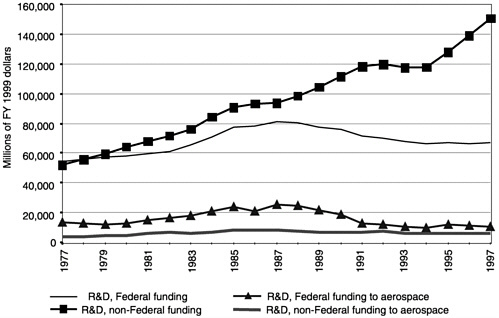

In 1977, 15 percent of the national investment in R&D was spent on aerospace. Today, as more and more R&D dollars are spent in other fields (e.g., pharmaceuticals, information systems, biotechnology), the proportion of investment

TABLE 4–1 U.S. Aerospace Industry Sales in the United States (in millions of constant FY01 dollars)

|

Year |

Total Sales |

Sales to DoD |

DoD’s Percentage of the Total |

|

1984 |

141,175 |

72,661 |

51 |

|

1985 |

159,825 |

88,010 h |

55 |

|

1986 |

170,211 |

94,835 |

56 |

|

1987 |

170,182 |

95,631 |

56 |

|

1988 |

170,125 |

91,071 |

54 |

|

1989 |

170,797 |

86,719 |

51 |

|

1990 |

180,600 |

81,315 |

45 |

|

1991 |

178,340 |

72,139 |

40 |

|

1992 |

173,516 |

65,357 |

38 |

|

1993 |

149,791 |

57,173 |

38 |

|

1994 |

131,122 |

51,941 |

40 |

|

1995 |

124,273 |

48,888 |

39 |

|

1996 |

130,829 |

47,489 |

36 |

|

1997 |

144,082 |

47,854 |

33 |

|

1998 |

159,534 |

46,286 |

29 |

|

1999 |

159,405 |

47,559 |

30 |

|

SOURCE: AIA, 2000, 2001a,b. |

|||

in aerospace has dropped to less than 7 percent (NSF, 2001). The full extent of these influences is shown in Figure 4–1.

In addition, the U.S. share in the world aerospace market declined from 70 percent in the mid-1980s to 55 percent in 1997 (NRC, 1999). In constant FY01 dollars, it went from $160 billion in 1985 to $146 billion in 1997, a 9 percent decrease (AIA, 2001b).

The environment in the commercial aerospace sector is being shaped by a rapidly expanding economy and by strong free-market forces. Growth in revenue and earnings is strong, the financial markets are supportive, and market capitalization for many industries has never been higher. The aerospace industry is now competing in a market with many technological opportunities and growing financial returns.

DoD is a monopsony (i.e., the only buyer) in the defense aerospace sector. A monopsonistic industry operates much differently than a competitive industry because the single customer ultimately provides the resources that attract workers and capital. There are few, if any, perfectly free markets anywhere with many suppliers and many buyers, perfect information, and no applied restraints. The DoD as a monopsony, or single buyer, for the defense industry cannot be said to operate in anything like a free market. This, however, does not mean that there is no competition, just that the competitions are established and controlled by DoD. The DoD has widely varying relationships with its suppliers, ranging from open competitions to what are essentially permanent single sources and everything in between. Since DoD sets the rules, it is responsible for the effects of these rules on its supplier base whether it recognizes this explicitly or not. Therefore, DoD is ultimately

FIGURE 4–1 Funding for R&D by source. SOURCE: Douglass, 2000a.

responsible for the health of the defense aerospace industry, although not for the health of any particular company.

Each of the services is the primary customer for a segment of the defense industry. As the primary customer for the defense sector of the aerospace industry, the Air Force has a significant share of responsibility for its viability. Therefore, the way in which the Air Force uses its resources will have a major impact on that sector of the defense aerospace infrastructure. The committee understands that this is well recognized within DoD but that there seems to be no established mechanism for determining and including the effects on the Air Force’s technical resources when decisions are being made about the competitive conditions for individual programs or for the Air Force program as a whole. The committee therefore recommends that this task be a responsibility of the recommended deputy chief of staff (DCS). Air Force management and budget decisions affect fundamental elements of the defense aerospace sector (e.g., program risk and stability, profit margins, proprietary ownership, investment in technology development, authority to transfer technology into commercial applications). Given the vulnerability of the defense aerospace sector, Air Force management would be well advised to take industry concerns into consideration in the development of its budget and management policies. In short, the Air Force has a responsibility and a crucial interest in making decisions that will ensure the health of this industry and that Air Force needs are met.