Chapter 4

The Role of Adaptive Behavior Assessment

NATURE AND DEFINITION OF ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR

Adaptive behavior has been an integral, although sometimes unstated, part of the long history of mental retardation and its definition. In the 19th century, mental retardation was recognized principally in terms of a number of factors that included awareness and understanding of surroundings, ability to engage in regular economic and social life, dependence on others, the ability to maintain one’s basic health and safety, and individual responsibility (Brockley, 1999). Today, fulfillment of these personal and social responsibilities, as well as the per-

This chapter contains material drawn from an unpublished paper commissioned by the committee from Sharon Borthwick-Duffy, Ph.D., University of California, Riverside.

formance of many other culturally typical behaviors and roles, constitutes adaptive behavior.

By the close of the 19th century, medical practitioners diagnosing mental retardation relied on subjective or unsystematic summaries of such factors as age, general coordination, number of years behind in school, and physiognomy (Scheerenberger, 1983). These practices persisted over that century because of the absence of standardized assessment procedures. And many individuals who would currently be considered to have mild mental retardation were not included in these early definitions.

Professionals voiced early caution about diagnosing mental retardation solely through the use of intelligence testing, especially in the absence of fuller information about the adaptation of the individual. In addition, mitigating current circumstances (not speaking English) or past history (absence of schooling) were often ignored in the beginning years of intelligence testing (Kerlin, 1887; Wilbur, 1882). At the turn of the century, intelligence assessment placed primary emphasis on moral behavior (which largely comports with the current construct of social competence) and on the pragmatics of basic academics. (Chapter 3 provides details on the development of intelligence assessment.)

Alternative measures to complement intelligence measures began to appear as early as 1916. Edger Doll produced form board speeded performance tests, which were analogues to everyday vocational tasks. During the 1920s, Doll, Kuhlmann, and Porteus sought to develop assessment practices consistent with a definition of mental retardation that emphasized adaptive behavior and social competence. Their work in this area sparked broadened interest in measurement of adaptive behavior among practitioners serving people with mental retardation (Doll, 1927; Kuhlman, 1920; Porteus, 1921; Scheerenberger, 1983).

Doll emerged as a leader in the development of a psychometric measure of adaptive behavior, called social maturity at that time. His work emphasized social inadequacy due to low intelligence that was developmentally arrested as a cardinal indication of mental retardation

(Doll, 1936a, p. 35). Doll objected to the definition of mental retardation in terms of mental age, which had proven problematic in IQ testing (because it resulted in classification of a significant proportion of the population). In 1936, he introduced the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (VSMS—Doll, 1936b), a 117-item instrument. The VSMS, which measured performance of everyday activities, was the primary measure used to assess adaptive behavior, social competence, or social maturity for several decades. One concern that emerged over time was that it was developed and normed for use with children and youth. It did not cover adults and had a limited range of items tapping community living skills (Scheerenberger, 1983).

The assessment of adaptive behavior became a formal part of the diagnostic nomenclature for mental retardation with the publication of the 1959 manual of the American Association of Mental Deficiency (Heber, 1959, distributed in 1961). The 1961 manual (Heber, 1961) discussed adaptive behavior with respect to maturation, learning, and social adjustment. This framework, reiterated in 1983, described adaptive behavior limitations consisting of “significant limitations in an individual’s effectiveness in meeting the standards of maturation, learning, personal independence, or social maturity that are expected for his or her age level and cultural group, as determined by clinical assessment and, usually, standardized scales” (Grossman, 1983, p. 11).

The 1983 manual characterized the tasks or activities encompassed by adaptive behavior (and, plausibly social competence) as:

-

In infancy and early childhood: sensorimotor development, communication skills, self-help skills, socialization, and interaction with others;

-

In childhood and early adolescence: application of basic academic skills in daily life activities, application of appropriate reasoning and judgment in mastery of the environment, and social skills—participation in group activities and interpersonal relations; and

-

In adolescence and adult life: vocational and social responsibilities.

During the 1960s, a wider variety of adaptive behavior measures was developed and disseminated (e.g., Allen et al., 1970; Balthazar & English, 1969; Leland et al., 1967). Indeed, by the late 1970s, the number of available adaptive behavior measures, largely interview or

observational in format, had burgeoned, including checklists pertaining to vocational behaviors (Walls & Werner, 1977). Measures developed in the 1960s have typically been updated in subsequent editions with enhanced psychometric characteristics and scoring (e.g., Sparrow & Cicchetti, 1985).

Over the past 25 years there has also been further refinement of the parameters and structure of tests of adaptive behavior and social competence. This refinement was based on large samples of research participants and data from service registries (McGrew & Bruininks, 1990; Siperstein & Leffert, 1997; Widaman et al., 1987, 1993). Novel frameworks for conceptualization of adaptive behavior have been proposed (American Association on Mental Retardation, 1992), and conventional frameworks have been endorsed for application in differential diagnosis and classification practices (Jacobson & Mulick, 1996). Finally, the difficulties and complexities of differentiating mild mental retardation from its absence or from other disabling conditions (e.g., Gresham et al., 1995; MacMillan, Gresham, et al., 1996; MacMillan, Siperstein, & Gresham, 1996) have remained an enduring concern in both professional practice and policy formulation.

Differing Conceptualizations

In Chapter 1 we summarized the history of definitions of mental retardation and discussed their relevance to the Social Security Administration’s definition. At first glance, current definitions seem to be quite similar; however, there are subtle differences in the conceptualization of adaptive behavior that may affect the outcomes of diagnostic decisions for individuals with mental retardation, particularly those in the mild range.

In the recent Manual of Diagnosis and Professional Practice in Mental Retardation (Jacobson & Mulick, 1996), Division 33 of the American Psychological Association put forth a definition of mental retardation that emphasizes significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior. The definition also views adaptive behavior as

a multidimensional construct, in that the definition is expanded to include “two or more” factor scores below two or more standard deviations. In describing mild mental retardation, there is minimal reference to adaptive behavior problems, except for the inclusion of “low academic skill attainment.”

It is important to note that the Division 33 definition places equal importance on the constructs intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior. The definition speaks to the presence of significant limitations in intellectual functioning and significant limitations in adaptive behavior, which exist concurrently. The term “concurrently” suggests an interdependent relationship in which both constructs are equally important. In this definition, the order of the constructs can be switched without affecting the validity of the definition.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), published by the American Psychiatric Association (1994), definition of mental retardation also has a cutoff of two standard deviations below the mean for intelligence, making an IQ cutoff of 70 to 75 acceptable for a diagnosis of mental retardation. In contrast, there is no mention of a standardized score or cutoff point for operationalizing any “significant limitations in adaptive behavior,” even though it is suggested that one or more instruments be used to assess different domains from “one or more reliable independent sources” (p. 40). The implicit rationale for not providing any statistical criteria for adaptive behavior testing is based on the existing limitations in instruments that measure adaptive behavior, specifically in terms of the comprehensiveness of measuring all domains and the reliability of measuring individual domains. Furthermore, issues are raised about the degree to which existing instruments are able to take into account the cultural context in assessing an individual’s adaptive behavior. One of the key themes throughout the DSM-IV definition is the cultural aspect of adaptive behavior. For example, adaptive behavior is defined in terms of effectively coping with common life demands and the ability to meet the standards of personal independence for a particular age group with a specific sociocultural background.

The DSM-IV definition identifies four levels of mental retardation based on IQ: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. No mention is made of the degree of severity of adaptive deficits for each of these levels, nor of the number or types of impaired adaptive behavior domains at each level. The DSM-IV definition places a greater emphasis than the Division 33 one on intelligence than on adaptive behavior, defining mental retardation as “significantly sub-average general intellectual functioning accompanied by significant limitations in adaptive functioning” (p. 39). In using the term “accompanied,” the definition suggests that adaptive behavior is a supplementary variable to intelligence, although both criteria must be present.

The World Health Organization (1996) also includes a definition of mental retardation in its International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). ICD-10 views the relationship between intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior as causal, with deficits in adaptive behavior resulting from deficits in intellectual functioning.

In describing the different severity levels of mental retardation, the ICD-10 guide presents IQ levels not as strict cutoffs but as “guides” to categorizing individuals with mental retardation. There is no mention of any standardized cutoffs for adaptive ability, except for mention of the use of “scales of social maturity and adaptation” in the measurement of adaptive behavior.

In the characterization of mild mental retardation, the ICD-10 guide points out that, “some degree of mild mental retardation may not represent a problem.” It goes on to state that the consequences will only be apparent “if there is also a noticeable emotional and social immaturity.” This statement implies that for individuals with mild mental retardation, intellectual deficits are apparent only when represented by problems in adaptive behavior (emotional and social immaturity). Furthermore, “behavioral, emotional, and social difficulties of the mildly mentally retarded . . . are most closely akin to those found in people of normal [range of] intelligence.” It is important to note that the terminology used in the ICD-10 is international English rather than North American English, and that, as a result, word usage in ICD-10 is

not entirely consistent with contemporary North American terminology with respect to functional limitations or depiction of social performance.

The most cited definition in the field is that of the American Association on Mental Retardation (AAMR). In their most recent classification system (American Association on Mental Retardation, 1992), AAMR defines mental retardation as subaverage intellectual functioning existing concurrently with limitations in adaptive skills. These limitations in adaptive skills are operationally defined as limitations in two or more of ten applicable adaptive skill areas (e.g. self-care, home living, social skills, self-direction, health and safety, etc.). The definition also includes the notion that adaptive skills are affected by the presence of “appropriate supports” and with “appropriate supports over a sustained period, the life functioning of the person with mental retardation will generally improve.”

AAMR departs significantly from other organizations by eliminating the grouping of individuals with mental retardation into levels of severity. AAMR no longer differentiates, either qualitatively or quantitatively, differences in intellectual or adaptive functioning of individuals with mild, moderate, severe, and profound mental retardation. Instead, they differentiate individuals with mental retardation based on the supports they need. The result is that the unique aspects and characterization of individuals with mild mental retardation are no longer the basis for differentiating them from more moderately and severely involved individuals. In so doing, AAMR ignores the substantial theoretical and empirical foundation that validates the difference between individuals with mild mental retardation and other individuals with mental retardation (MacMillan et al., in press).

Among these four definitions, there is little variation in the intelligence construct for individuals with mental retardation. The differences occur rather in their consideration of the contributing role of adaptive behavior. In some definitions (Division 33 and AAMR), adaptive behavior is construed as distinct from intellectual functioning and of equal importance, while in other definitions it is considered a result of deficits in intellectual functioning. The definitions also

vary as to whether they consider adaptive behavior to be made up of a single factor or to have multiple factors or domains. In the definitions that imply a multifactor construct, deficits in adaptive behavior must be specified in a certain number of areas/domains. With regard to identifying decision-making criteria, Division 33 presents the only definition that employs a statistical cutoff based on standard norms. In contrast, the other definitions employ more qualitative terms, which are open to interpretation in describing deficits and limitations in adaptive behavior.

Dimensions of Adaptive Behavior

Structure

Multidimensional or Unidimensional? Answers to this question have been mixed. Meyers et al. (1979) concluded from their review of factor analytic studies that adaptive behavior was definitely multidimensional and that the use of a total score would be inappropriate to indicate a general level of adaptation. Their view has been both supported and disputed in the past two decades, and there are currently firm adherents on each side of this issue. McGrew and Bruininks (1989) and Thompson et al. (1999) have concluded, for example, that the number of factors emerging from factor analyses depends on whether data were analyzed at the item, parcel, or subscale level, with fewer factors found for subscale-level data than item- or parcel-level data.

They also found that it was not the selection of the instrument that determined the number of factors. This important finding has direct implications for definitions that require limitations to be observed in a specific number of areas. If there is actually one underlying domain that “causes” behaviors in all different conceptual domains, and there is relatively little unique variance found in each domain, then a total score with a single cutoff point could reliably distinguish those with and without significant limitations. If not, diagnosticians would have to consider a profile of adaptive behavior deficits that takes all domain scores into account. Widaman et al. (1991) and Widaman and

McGrew (1996) concluded that evidence supported a hierarchical model with four distinct domains: (1) motor or physical competence; (2) independent living skills, daily living skills, or practical intelligence; (3) cognitive competence, communication, or conceptual intelligence; and (4) social competence or social intelligence. Widaman and McGrew (1996) further argued that agreement on a common set of terms for domains of adaptive behavior (in contrast to the use of “or” as above) would contribute to a better consensus on the structure of adaptive behavior.

The review by Thompson et al. (1999) is the most recent summary of studies using factor analysis; it concludes that adaptive behavior is a multidimensional construct. The three most common dimensions found were in these broad categories: (1) personal independence, (2) responsibility, i.e., meeting expectations of others or getting along with others in social contexts, and (3) cognitive/academic. Physical/developmental and vocational/community dimensions were found less often. Thompson et al. concluded: “No single adaptive-maladaptive behavior assessment instrument completely measures the entire range of adaptive and maladaptive behavior dimensions. . . It is clear that different scales place different levels of emphasis on different adaptive behavior domains. No one instrument produced a factor structure that included all of the domains” that were identified by the American Association on Mental Retardation (1992).

Breadth of Domains. The domains assessed by adaptive behavior scales, and thus the individual items included on them, depend in part on the context, target age group, and purpose of the measure. Thus, considerable variation has been found in the content covered by different scales (Holman & Bruininks, 1985; Thompson et al., 1999). Measures used in schools may not need a work domain, for example, if students are too young for employment or the school does not have a work experience program. Conversely, adult scales would not need items on school-related behaviors (Kamphaus, 1987a). In their review, Thompson et al. (1999) suggest that this incongruity reflects the problem noted by Clausen (1972) and Zigler et al. (1984), that adaptive behavior lacks

a unifying theoretical foundation. A consequence of this, according to Thompson et al., is the inability to develop precise measures of adaptive behavior that would objectively differentiate individuals by disability. An alternative explanation is that adaptive behavior must be understood in the context of the individual’s relevant daily and social life, which is determined by age, culture, and context (Thompson et al., 1999).

Independence of Domains. The 1992 AAMR definition requires that an individual show significant limitations in at least 2 of the 10 adaptive skill areas. A danger of accepting “erroneous domains that are not truly distinct from one another” (Thompson et al., 1999, p. 17) is that it can lead to the inconsistent application of eligibility criteria and unequal treatment across groups of people. Thus, characteristics of the factor structure of a measure of adaptive behavior have important implications for diagnosis.

Thompson et al. (1999) reviewed studies that reported factor analyses of adaptive behavior measures. They made two important points before summarizing their findings: (1) highly correlated factors may indicate that they do not represent independent dimensions and (2) different methods of factor analysis can support different factor structures.

Domains Missing from Adaptive Behavior Scales

Greenspan (1999) noted that a drawback to the factor analytic approach to determining the dimensional structure of adaptive behavior is that this statistical method cannot determine whether some domains do not make conceptual sense (i.e., items should not have been included on tests in the first place) or whether missing content domains should have been included.

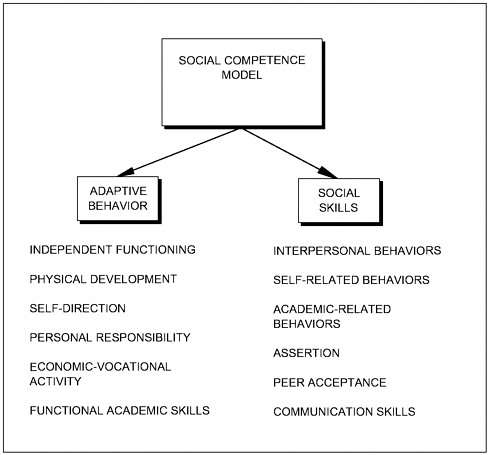

Social Skills Dimension of Social Competence. Most adaptive behavior scales contain factors addressing interpersonal relationships or social skills, but they do not address overall social competence. For indi-

viduals whose diagnosis is most in question because their measured IQs are near the cutoff, this vital area may determine the presence or absence of mental retardation. Gresham and Elliott (1987) and Greenspan (1999) have argued that social competence has received too little attention in the conceptualization and measurement of adaptive behavior (Figure 4-1). Their model divides social competence into two overall dimensions: (1) adaptive behavior, which includes the factors contained on most adaptive behavior scales (independent functioning, self-direction, personal responsibility, vocational activity, functional academic skills, physical development) and (2) social skills, including domains that are likely to be most key to identifying mental retardation at the borderline levels (interpersonal behaviors, self-related behaviors, academic-related skills, assertion, peer acceptance, communication skills). The dimensions of adaptive behavior and social skills in the Gresham and Elliott model are surprisingly similar to the 10 adaptive skill areas in the 1992 AAMR definition of mental retardation.

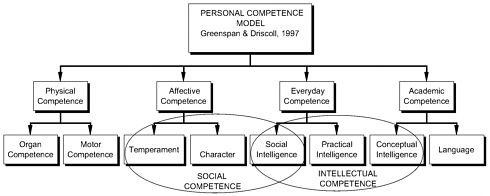

Gullibility/Credulity Component of Social Competence. Greenspan and colleagues (Greenspan, 1999; Greenspan & Driscoll, 1997; Greenspan & Granfield, 1992) have argued that social intelligence, some aspects of which are not contained on any current scales of adaptive behavior or social skills (e.g., credulity, gullibility), should be a key determinant of a diagnosis of mental retardation for adults (Figure 4-2). Greenspan and Driscoll (1997) proposed a “dual nature of competence.” They suggest that intelligence, as measured by IQ, is typically viewed as an independent variable that predicts outcomes, whereas personal competence is the combination of what individuals “bring to various goals and challenges as well as their relative degree of success in meeting those goals and challenges” (p. 130).

Greenspan (1999) argues that the victimization of people with mental retardation, observed in social and economic exploitation, is “a more central (and generally more subtle) problem that goes to the heart of why people with mental retardation are considered to need the protections (ranging from in-home services to conservators) associated

FIGURE 4-1 Social competence model. SOURCE: Gresham & Elliott (1987). Copyright 1987 by PRO-ED, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

with the label” (p. 69). Very recently Greenspan (1999) proposed ideas for assessing vulnerability in a comprehensive assessment of adaptive behavior or social competence. As there is no research yet on credulity in people with mental retardation, these proposals for assessment are unlikely to be found in practice in the next several years. Nevertheless, there is merit to the idea of considering these subtle indicators of social competence, i.e., vulnerability, gullibility, and credulity, as important indicators of adaptive behavior in people with mild cognitive impairments.

Maladaptive Behavior

Many adaptive behavior scales contain assessments of problem or maladaptive behavior, but relationships between domains of adaptive and maladaptive behavior are generally low, with correlations tending to be below .25 (and a tendency to be higher in samples of persons with severe or profound retardation—Harrison, 1987). Division 33 makes it clear that the presence of clinically significant maladaptive behavior does not meet the criterion of significant limitations in adaptive functioning (Jacobson & Mulick, 1996). Hill (1999) also emphasized that behaviors that interfere with a person’s daily activities, or with the activities of those around him or her, should be considered maladaptive behavior, not the lack of adaptive behavior. Refusal to perform a task that a person is capable of doing is also a reflection of problem behavior and should not be considered in relation to adaptive behavior. The classroom form of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow & Cicchetti, 1985) does not include a section on maladaptive behavior, which also suggests that these authors viewed measures of problem behavior as irrelevant to diagnosis or eligibility. Greenspan (1999) also has argued for many years that the presence of maladaptive behavior, or mental illness, is irrelevant for the purpose of diagnosing of mental retardation.

If it is assumed that maladaptive behavior ratings should not contribute to diagnostic decisions about adaptive functioning, then problems in their measurement need not affect this process. However, because several adaptive behavior scales contain maladaptive components, it is worth noting important challenges to reliable measurement. Specifically, several roadblocks to meaningful ratings of maladaptive behavior were noted after publication of the original AAMD Adaptive Behavior Scales (ABS). Scales developed subsequently improved on the simple rating format found in the ABS, which contained a finite list of problem behaviors rated according to the frequency of occurrence. These improvements notwithstanding, the complexity of balancing frequency and severity of problem behavior occurrence will continue to pose problems of score interpretation.

ASSESSMENT OF ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR

Assessment Dimensions

The assessment of adaptive behavior is complex. One must consider not only general competencies across relevant domains but also the level, quality, and fluency of those behaviors. In addition, there is the issue of the ability to perform behaviors (i.e., can do) versus the actual performance of those skills (i.e., does do). In order for the assessment to be clinically and scientifically meaningful, it is important that the assessor be sufficiently trained in using and interpreting appropriate instruments. A high level of training is necessary in order to capture and distinguish the level, quality, and pattern of adaptive behavior displayed by a given subject, as viewed by the eyes of the respondent (parent, teacher, or caregiver).

The frequency of performance can be classified along a dimension from “never” to “usually or always.” The number of choice points varies by specific instrument or by the variation in the clinical interpretation of the assessor when a formal assessment instrument is not used. The quality of performance may be somewhat more subjective, but a key feature is the appropriateness of a given level of adaptive behavior performance. For example, one needs to distinguish between an individual’s deficit in a specific adaptive behavior skill, as opposed to a deficit in a larger domain.

Assessment Methods

There are a number of ways to assess the level, quality, and pattern of adaptive functioning, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. These include clinical assessment by interview methods (unstructured, structured, semistructured, direct observation), usually with the aid of clinical instruments that are completed by the evaluator during the interview, and the use of checklists that are completed either by an observer or by the individual being assessed.

In an unstructured interview, the clinician applies personal, experience-based clinical norms to the adaptive behavior assessment. The advantage of the method is that it frees the clinician from using a set of criteria that may be perceived as restrictive. The disadvantage is that each clinician imposes his or her own subjective criteria, a process that threatens both the reliability and the validity of the assessment.

Both structured and semistructured interviews, when performed by well-trained and experienced clinicians, appear to be the best available safeguard against threats to the reliability and the validity of adaptive behavior assessment. These procedures, however, need to be employed using an instrument that is reliable, has valid criteria for evaluating adaptive behavior, and uses empirically based norms. In fact, semistructured interviews require the highest level of professional expertise, as the questioning and interpretation of answers requires a high level of training.

Since the adaptive behaviors that need to be assessed are those found in the context of a broad range of everyday living situations displayed across a wide variety of settings, an assessment of adaptive functioning by direct observation is usually not practical. It would be difficult to set up situations in which individuals can demonstrate their ability to perform a wide variety of social, communicative, and daily living behaviors.

Checklists completed by teachers, parents, or other caregivers are often used to rate individuals’ behavior for a broad variety of suspected conditions (e.g., mental retardation, autism, other pervasive developmental disorders, attention deficit disorder). However, the simplicity and lack of reliability or validity of many such procedures render them less useful than more complex measures administered professionally. Checklists may add valuable information and insights, but they are seldom solely sufficient for diagnostic purposes. In order to make reliable and valid judgments about the presence or absence of many behaviors, the items may need such extensive clarification as to obscure the meaning of such behaviors for many respondents.

The issues of cross-cultural, racial, ethnic, and subcultural biases

are of concern to some who view many aspects of adaptive functioning as culturally determined (Boyle et al., 1996; Valdivia, 1999—for a general discussion see the section “Sociocultural Biases”). The issue of sociocultural bias also arises in the context of the adaptive behavior interview. Administration of adaptive behavior scales generally follows one of two possible formats. One is an interview with a professionally trained interviewer and a respondent who knows the individual being assessed well. The other consists of a person who also knows the individual being assessed well but who independently completes a checklist of specific items without assistance. Other scales permit someone to help the person answer questions that cannot be answered without assistance. Some scales can be administered either way. When trained professionals use an interview format, the phrasing of items contained in the record booklet is not used. In this format, the professional has the opportunity to ask questions that are at the appropriate level of sophistication and also appropriate to the cultural group of the respondent.

Adaptive behavior is generally not a mental health issue, since the focus is on developing positive behaviors, rather than deficits. Thus, some of the concerns about cultures that are less accepting of mental illness labels than the majority culture are much less relevant to adaptive behavior assessment.

There seems to be little evidence that adaptive behavior assessment is as prone to cultural, racial, and ethnic bias as other areas of psychological testing. For example, adaptive behavior tests are not as culturally or ethnically bound as tests of intelligence (Hart, 2000; Hart & Risley, 1992; Sparrow et al., 1984a; Walker et al., 1994). However, a recent surgeon general’s report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001) focuses on the miscommunication that may exist when the interviewer and the respondent speak different languages. The report notes that “several studies have found that bilingual patients are evaluated differently when interviewed in English as opposed to Spanish.” It is also possible that different subcultural expectations about independence or religious or medical causes for certain behav-

iors may affect the validity of reports. In such instances, if a same-language or same-culture interviewer is not available, the clinician needs to be very aware of such possible miscommunications in order to obtain a valid interview. The surgeon general’s report emphasizes that more research is needed to better understand how, when, and if culture affects interview-based assessments.

Psychometric Concerns in Using Adaptive Behavior Scales

The primary use of adaptive behavior scales in the classification of mental retardation has frequently been confirmatory (i.e., to confirm that a low IQ is associated with delayed acquisition or manifestation of everyday personal and social competencies). This use may result from concerns among clinicians about the robustness of adaptive behavior measures. For the most part, such concerns result from considerations of the structure of measures (e.g., as related to items and other factors mentioned in this section), procedures for obtaining information used to complete the protocols, and issues surrounding informant bias.

Such concerns arise in part because intellectual performance, the other criterion associated with mental retardation, is measured by comprehensive intelligence tests that are the most thoroughly researched forms of psychological assessment (Neisser et al., 1996). Research studies in the past decade that employ adaptive behavior measures have used them as outcome measures or to study the structure or dimensions of adaptive behavior, rather than behavioral development. Clinicians may consequently believe adaptive behavior to be less well understood than intelligence. Nonetheless, there is a rich literature documenting differential outcomes for quality of life, autonomy, and clinical decision making for adaptive behavioral development as measured by existing assessment instruments (Jacobson & Mulick, 1996). Newer adaptive behavior scales evidence more robust psychometric properties than older scales. In this section, we discuss a variety of psychometric features of adaptive behavior scales that have implications for decision making about mental retardation.

Floor and Ceiling Effects

The initial, and probably primary, application of adaptive behavior scales in clinical practice has been to assess the behavioral development of children thought to have mental retardation. Thus, most norming samples, item development, and scale selection have been targeted at groups ages 3 to 18 or 21. This facilitates the early identification of preschool children at risk of mental retardation and permits confirmation of persisting developmental delays. Adult norming samples are often included as well, but they tend to consist of people with already identified disabilities. Thus, adaptive behavior scales have particular relevance in application with preschoolers and with teens, who are often participants in Supplemental Security Income (SSI) determinations or redeterminations. However, depending on the age range of adult participants without disabilities sampled during norming studies, the ceiling (i.e., the highest level of behavioral performance assessed) may differ across scales and may affect the characterization of the degree of delay manifested. Measures of behavioral functioning or responsiveness of children younger than 36 months have not been strengths of many adaptive behavior measures. Infants and toddlers may more appropriately be assessed with more specialized measures in most cases.

Developmental Range Effects

Floor and ceiling effects are also evident as developmental range effects. Scales typically include items that permit behavioral assessments for young children and adolescents without disabilities (i.e., superior behavioral development or skill). For older adolescents, ages 18 to 21, the difficulty level of items often permits identification of either delayed or typical skills. Thus, to the extent that a young adult with mild mental retardation has selected skills that are well developed relative to others, it may not be accurate to describe those skills in developmental terms. Instead, it may be possible to establish only that their skills are superior to those achieved by other young adults with

mild mental retardation, and they may sometimes fall in the normal range of performance of similar age peers. Some data suggest that ceiling and developmental range effects hinder the full description of skill assets for some individuals with mild mental retardation. In unpublished data on some 27,000 people with mild mental retardation, between 75 and 100 percent of participants obtained perfect scores (100 percent) on three of five indices of one scale (J.W. Jacobson & C.S. Brown, personal correspondence, June 17, 2001).

Item Sampling in Relation to Age-Typical Behavior and Settings

Because adaptive behavior scales are designed with applicability for a wide age range but with primary emphasis on childhood and adolescence, some items may not be suitably worded or may not reflect a performance that is age-relevant. For example, an item may tap skills associated only with childhood (e.g., performing a specific activity or completing a task with adult assistance in an age-typical manner) or with adulthood (e.g., menstrual care for an adult or adolescent woman). Some scales contain provisions for alternative items or alternative performance of items. However, depending on the nature of these provisions, they may reduce the comparability of measures of the related skills from different adaptive behavior scales.

In other instances, scales may be constructed such that they are relevant to only certain age groups (e.g., the motor scale in the Vineland ABS), or different versions of the same scale may be used in different settings (e.g., school versus residential and community settings). For example, the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (Harrison & Oakland, 2000a) is available in four forms: parent, teacher, adult self-report, and adult reported by others. The two versions of the AAMR ABS differ with respect to the age groups emphasized and the settings about which items are structured and weighted in item selection. For example, in relation to the AAMR school-age scales, “items were selected in part based on discrimination among institutionalized individuals and community dwelling individuals previously classified at

different adaptive behavior levels, and among adaptive behavior levels in public school populations” (Lambert et al., 1993b).

Item Density

Adaptive behavior scales are structured to be comprehensive without being cumbersome (Adams, 2000). Consequently, several features must be balanced. A number of factors and descriptive categories of behavioral development must be represented adequately in order to ensure comprehensiveness and documentation of both strengths and limitations for clinical and diagnostic purposes. The number of items associated with each descriptive category must be sufficient to provide a scale and to be applicable across age ranges. A relatively wide age range must be represented. In balancing these factors, item density, that is, the inclusion of multiple items reflecting age-typical performance at a range of ages, must be maintained at a fairly uniform level. This means that within any one subscale of an adaptive behavior scale, for example, there may be only one or two items typical of performance for a 10-year-old. When subscale scores are aggregated into summary scores, this results in a meaningful number of age-relevant items, although the items sampled in each subscale are limited. For this reason, some manuals recommend that clinicians fully explore the nature of tasks that the focal person performs that may be age typical (e.g., Sparrow et al., 1984a). Nonetheless, it should always be recognized that items in adaptive behavior measures represent a sampling of items that have passed reliability and validity screens, rather than a complete characterization of adaptive behavior.

Reliability of Informant Judgments

Because adaptive behavior scales are typically completed through interview of informants or direct responses (marking of a protocol by the informant), the reliability and the validity of informant responses have been particular concerns. These concerns are heightened when

informants have a stake in the outcome of the assessment (e.g., when responses may affect eligibility for services). Developers have addressed this issue through several strategies: (1) assessing the interrater and test-retest reliabilities of measures, (2) providing instructions to raters for coding items (e.g., Sparrow et al., 1984a), and (3) specifying training for clinicians and preparation of raters (e.g., Bruininks et al., 1996). Reliabilities are initially assessed at the item level and then at the scale and factor levels. Current measures evidence acceptable interrater and test-retest reliability, with consistency scores at levels of .90 and above (seldom at a level below .80) for clinical and normative subgroups, partitioned by age and clinical variables. Similarly, adequate internal consistency of subscales or domains is documented using split-half or alpha coefficients. Full details on standardization and reliabilities are provided in the manuals associated with the major adaptive behavior scales (Adams, 2000; Bruininks et al., 1996; Harrison & Oakland, 2000b; Lambert et al., 1993b; Sparrow et al., 1984b; see also Harrington, 1985). Additional discussion is provided in Chapter 3.

Validity of Informant Judgments

Validity can be categorized in terms of: (1) content validity (evidence of content relevance, representativeness, and technical quality); (2) substantive validity (theoretical rationale); (3) structural validity (the fidelity of the scoring structure); (4) generalization validity (generalization to the population and across populations); (5) external validity (applications to multitrait-multimethod comparison); and (6) consequential validity (bias, fairness, and justice; the social consequence of the assessment to the society—Messick, 1995). Technical manuals present analyses of data gathered in the process of test development that addresses content validity (in terms of representativeness and inferences from age norms), substantive validity (in that they present either a theoretical or empirically derived model of adaptive behavior to which the scale conforms), generalization validity (with respect to differing age or disability groups), external validity (in terms of concurrence with previous or contemporary adaptive behavior measures

and intellectual measures), and consequential validity (in terms of evidence of bias or procedures utilized to reduce bias). As previously noted, primary concerns in the use of adaptive behavior scales in eligibility determination decisions center on informant bias.

Manuals for the major adaptive behavior scales encourage the use of multiple informants, for example, teachers and parents. This allows the rater to obtain a complete picture of the adaptive functioning of the person being assessed. It also allows for reconciliation of ratings among these informants. Both legislative action and judicial decisions at the federal level have focused on concerns that parents may misinform clinicians regarding their children’s skills in order to obtain SSI benefits. Federal review of the SSI program has indicated that such deception is an uncommon occurrence.

Adequacy of Normative Samples

Another psychometric concern is whether the norming samples are adequate. Although normed on smaller samples than comprehensive intelligence tests use, current adaptive behavior measures typically have adequate norming samples in relation to both representation of people with and without mental retardation and representation of age groups in the population in relation to the age span of the measure.

-

For the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (Harrison & Oakland, 2000a), the norming groups for 5- to 21-year-olds included 1,670 (parent form) to 1,690 (teacher form) children; for 16- to 89-year-olds, the norming groups included 920 (rated by others) to 990 (self-report) adults without disabilities throughout the United States.

-

For the Scales of Independent Behavior-R (Bruininks et al., 1996), the norming sample included 2,182 people ages 3 years 11 months to 90 years, with a sampling frame based on the general population of the United States stratified for gender, race, Hispanic origin, occupational status, occupational level, geographic region, and community size.

-

For the AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale-School scales (Lam-

-

bert et al., 1993a) the norming group included 2,074 students (ages 3-21) with mental retardation living in 40 states, and a sample of 1,254 students (ages 3-18) without mental retardation from 44 states.

-

For the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow et al., 1984a) the standardization sample was representative of the U.S. population. It consisted of 3,000 children ages birth through 18 years 11 months of age, including 99 children in special or gifted education among the 2,500 who were of school age.

-

For the Comprehensive Test of Adaptive Behavior-R (Adams, 2000), the norming sample represented four of five U.S. regions (excluding the West) and included a nonschool sample of 4,456 people with mental retardation ages 10 to 60+ years and a school sample of 2,094 children and adolescents with mental retardation ages 5 to 22, and a sample of 4,525 children and adolescents without mental retardation ages 5 to 22.

Sociocultural Biases

Bias refers to a consistent distortion of scores that is attributed to demographic factors, principally nonmodifiable personal characteristics such as age, gender, race, and ethnic or cultural membership. In the United States there have been significant concerns about the relationship between ethnicity or racial origin and performance on intelligence tests (Neisser et al., 1996). This has generalized to adaptive behavior measures. As the importance of adaptive behavior measures in classification of mental retardation has increased, this concern has been heightened as disproportionate numbers of minority children have been identified as having mental retardation, primarily because of low-income status and the overrepresentation of individuals with mental retardation among low-income people (Boyle et al., 1996).

Some (e.g.,Valdivia, 1999) have suggested that age norms are arbitrary and reflect white, middle-class childrearing standards, and that developmental attainments are affected by culturally different skills and expectations. The result is an overidentification of skill limita-

tions among minority children. However, research that indicates a causal relationship between the childrearing practices of minority families in North America and developmental delay is very limited. Comparative research examining the relationship between minority status and pronounced delays that are not accounted for by socioeconomic factors is also limited. However, available data are sufficient to raise concerns that such issues should be studied further (Bryant et al., 1999; Craig & Tasse, 1999).

To some extent, inclusion of participants representative of the general population, including racial and ethnic minorities, in norming samples should mitigate against biases in scoring of adaptive behavior scales. To the extent that low income or very low income is more common among certain ethnic minority groups, however, differences in developmental trajectories for children may reflect differences in childrearing practices and stimulation that are associated with economic and social class and related levels of parental education (Hart, 2000; Hart & Risley, 1992; Walker et al., 1994).

Although research from the 1970s and 1980s found comparable performance on adaptive behavior scales among majority and minority ethnic groups (Bryant et al., 1999; Craig & Tasse, 1999), linguistic factors remain a concern. These include such considerations as interviewing informants in their primary language and dialect, and the comparability of translations of items in adaptive behavior scales to particular languages and dialects, including dialects in English (e.g., American and British). Translation is a concern because the comparability of translations of items has seldom been confirmed through back-translation from the translated content to the initial language, or through confirmatory analysis through further retranslation (Craig & Tasse, 1999). Noncomparability of items may alter norms due to item wording that requires a higher developmental level of performance in the translated item. Also, English language norms may be lower than the typical performance of a same-age child in another culture. Cross-cultural and cultural subgroup studies of adaptive behavior differences among ethnic, racial, or national groups are certainly needed, but evi-

dence for substantial relationships between racial or ethnic group membership and performance on adaptive behavior scales, unmediated by socioeconomic differences, is very limited.

Nonetheless, culturally competent assessment practices require consideration of the developmental impacts of cultural practices or language differences among examiners, examinees, and informants that may affect the validity of the clinical information collected and interpreted. Under ideal circumstances, adaptive behavior measures should be administered in an examinee’s or informant’s primary language. Often, there may be no substitute for assistance by a translator familiar with the informant’s dialect, even for examiners who are fluent in the informant’s primary language. In instances in which the informant is bilingual, it may be appropriate to probe interview responses in both languages.

Adaptive Behavior Scales with Well-Known Properties

There are at least 200 published adaptive behavior instruments that have been used for diagnosis, research, program evaluation, administration, and individualized programming. Some of these scales were developed to serve only one of these purposes; however, several have attempted to include both the breadth required for diagnosis and the depth required for clinical use. Most tests fall short of accomplishing both purposes. Referring to the dual purpose of adaptive behavior scales, Spreat (1999) concluded that it is “unrealistic to think that the same test can be used for program evaluation, diagnosis, classification, and individual programming” (p. 106). Among the very large number of adaptive behavior scales on the market, very few have adequate norms and reliability to diagnose mental retardation in people with IQs in the questionable range (e.g., 60-80). Kamphaus (1987b) reported that the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-Survey Form (Sparrow et al., 1984a) and the Scales of Independent Behavior (Bruininks et al., 1984) had adequate standardization samples. In a national survey of school psychologists, only three scales were found to be in wide use for diagnosis: the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, the Scales of

Independent Behavior, and the AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale-School Edition (Stinnett et al., 1994). The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (Harrison & Oakland, 2000a) is quite new and relatively untested, but its psychometric properties and norms extend to age 89.

Each of these scales (except the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System) has been reviewed extensively and compared with others in detailed reports. Readers are referred to the test manuals and to Reschly (1990), Harrison and Robinson (1995), Thompson et al. (1999), Jacobson and Mulick (1996), Spector (1999), Hill (1999), Test Critiques, test reviews in the Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, and the Mental Measurements Yearbooks for more detailed psychometric information about these and other measures. Although each scale described has both strengths and weaknesses, each has impressive psychometric characteristics and is highly recommended for use in eligibility determination and diagnosis. Decisions about which instrument to use depend on the age of the individual to be tested and available norms, available sources of information, the context in which the individual is known, and the training of the rater.

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS—Sparrow et al., 1984a) have their conceptual roots in the Vineland Social Maturity Scale (Doll, 1936b), although overlap between the original and the new scales is minimal (Kamphaus, 1987b). There are actually three scales, including a survey form (VABS-S) and an expanded form (VABS-E), which uses a conversation data gathering format during interviews with parents or guardians. A psychologist, social worker, or other professional who has appropriate training in interview techniques must complete these forms. Norms on children having no disability are available from birth to 18 years, 11 months, based on a standardization sample of 3,000 cases that were stratified by age, gender, ethnicity, parental education, geographic region, and community size consistent with U.S. census data. The proportion of children from homes with low socioeconomic status was lower than that in the cen-

sus data. The expanded version is designed to meet the requirements of diagnosis and of planning/intervention, and is intentionally longer and more detailed in order to ascertain information on specific skill deficiencies. Data from reliability and validity studies of the survey form are very impressive, especially in light of the flexible conversational procedures used for obtaining information.

The third scale is a classroom form (VABS-C), appropriate for children ages 3-12, and can be completed by the teacher fairly quickly. It does not require specific or graduate training to complete. However, teachers have limited opportunities to observe all behaviors on the VABS-C and must necessarily provide estimates of behaviors that do not occur in the school context. A strength of this scale is that teachers are asked to record when they estimate behaviors, so the resulting threat to reliability and validity can be appraised.

AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scales

There are two versions of the Adaptive Behavior Scales (ABS)–a school version (ABS-S:2—Lambert et al., 1993a) and a residential and community version (ABS-Residential and Community, ABS-RC:2— Nihira et al., 1993). The ABS-S:2 is used to identify students who are significantly below their peers in adaptive functioning for diagnostic purposes. It also determines strengths and weaknesses, documents progress, and assesses the effects of intervention programs. Although it is linked to AAMR by name, the ABS does not provide subscale scores in the 10 adaptive skill areas listed in the 1992 AAMR definition of mental retardation. Stinnett (1997) matched ABS items to the 10 adaptive skill areas in the AAMR definition and found that some skill areas are addressed in depth by the ABS (social skills and self-care domains), while others have too few items to give reliable estimates (home living, health and safety, leisure). Nine behavior domains measure personal independence and personal responsibility in daily living, including prevocational/vocational activity. A second part of the ABS-S relates to social and maladaptive behavior.

The ABS-S was standardized on population samples of people

with and without mental retardation. Standard scores, age-equivalent scores, and percentile rank scores can be converted from raw scores on the adaptive behavior subscales and three factor scores for ages 3-21. The standardization samples have been judged to be excellent, although the fact that the sample of people with mental retardation did not include people in the IQ range 71-75 is likely to overestimate adaptive behavior when using the mental retardation norms (Stinnett, 1997). Since other norms should be used for determining a diagnosis of mental retardation, according to the manual, this should not be a problem in the current SSA context. The ABS-S:2 has excellent interrater reliability.

The ABS-S:2 provides norms only through age 21 and includes some content specifically appropriate for school settings rather than adult environments. The residential and community version, ABS-RC:2, was developed to be appropriate for use with persons through 79 years of age. ABS-RC:2 norms are not available for adults with typical functioning, and most norm-referenced scores provide comparisons only with adults with developmental disabilities. The standardization sample consisted mostly (80 percent) of adults living in residential facilities, and the overall functioning level of the sample may be lower than if other community-dwelling adults had been included (Harrison, 1998). Because standard scores and percentile ranks do not indicate standing relative to people without developmental disabilities, and because the norming sample is probably not representative of the population of adults with developmental disabilities, the ABS-RC:2 may not fit the psychometric criteria used in determining a diagnosis of mental retardation according to AAMR requirements (American Association on Mental Retardation, 1992).

Scales of Independent Behavior

The Scales of Independent Behavior (SIB-R—Bruininks et al., 1984) is a component of the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery. The SIB provides norms from infancy to adulthood (40+ years), contains 14 adaptive behavior subscales that fall into four ma-

jor clusters, and provides an additional full-scale broad independence score.

The SIB-R manual addresses many of the issues that make the scoring interpretation of adaptive behavior scores challenging, including physical disability, the use of adaptive equipment, alternative communication methods, tasks no longer age appropriate, partial performance of multipart tasks, lack of opportunity due to environment or safety, and cognitive ability to understand social expectations for performing behaviors. In general, individuals are to be rated according to what they actually do (or would do if age appropriate), rather than giving “credit” for these considerations or denying credit if tasks are performed well with the assistance of adaptive equipment, medication, or special technology (Hill, 1999). However, if functional independence is to be considered “within the context of the environments and social expectations that affect his or her functioning” (Hill, 1999), interpreting scores without considering opportunity and societal expectations for a person with physical limitations could be problematic for a diagnosis of mental retardation.

Adaptive Behavior Assessment System

The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS—Harrison & Oakland, 2000a) is the newest of the adaptive behavior measures that has sound psychometric properties. Although it had extensive field testing before publication, formal reviews are not yet available. It was developed to be consistent with the 10 AAMR adaptive skill domains, and, depending on the weight placed on using the AAMR definition for diagnosis by a clinician, this may be a relevant characteristic. Moreover, the ABAS is appropriate for use with children (age 5 and older) as well as adults. It includes two adult forms, including a self-report and a report by others, and norms that extend well into adulthood. It appears to have good potential for assessing adaptive behavior for diagnostic purposes. Average reliability coefficients of the adaptive skill areas across age groups range from .86 to .97, with the majority above .90 and corrected reliability coefficients of individuals with clinical di-

agnoses above .98. Norms for age birth to 5 years are expected to be available in 2002.

Battelle Developmental Inventory

The Batelle Developmental Inventory (BDI—Newborg et al., 1984) is a developmental scale, rather than an adaptive behavior scale, and is appropriate for children from birth to age 8 (Spector, 1999). It does not have the problems with floor effects in diagnosing developmental delays at the youngest ages that are present in other adaptive behavior scales. It contains broad domains similar to those found on adaptive behavior scales, which include: personal-social, adaptive, motor, communication, and cognitive. The BDI has well-documented reliability and validity, with norms based on a nationally representative sample of children (Harrington, 1985; Oehler-Stinnett, 1989). Several studies have shown significant and meaningful correlations between the BDI and other measures of cognitive, adaptive, language, and social functioning, with samples of children with and without disabilities (Bailey et al., 1998). The BDI is susceptible to “age discontinuities” (Boyd, 1989) or “differences in norm table layout” (Bracken, 1988) that are relatively common in measures of young children during this period of typically rapid development. This problem, and recommended strategies to avoid errors in diagnosis, are discussed in the section on norms.

Other Scales

The adaptive behavior scales described above have been consistently identified in research and practice reports as meeting criteria of technical excellence in measurement. Several other tests have been widely used and have many positive features but do not have the same reputation. Because clinicians are encouraged to utilize multiple measures in diagnosis, these other measures may be useful in providing supplemental or complementary information.

The Comprehensive Test of Adaptive Behavior (CTAB—Adams

& Hartleben, 1984) has been described as “fairly efficient and inexpensive,” with “excellent reliability, solid validity, and adequate norms” (Reschly, 1990). It is reported to be appropriate for ages 5-22, yet it may not have a sufficient ceiling to discriminate performance levels among children above age 14 (Evans & Bradley-Johnson, 1988). A second limitation of this scale is that the standardization sample was limited to the state of Florida. Because Florida is a large and populous state with a culturally diverse population, it is likely that results can be generalized to the national population. Scores on the revised version of this measure, the CTAB-R, are based on a standardization sample that includes four of five regions of the United States (Adams, 2000).

The Adaptive Behavior Inventory (ABI—Brown & Leigh, 1986) was designed to “reflect the ability of school-age youngsters to meet age-appropriate socio-cultural expectations for personal responsibility” (Smith, 1989). It is appropriate for use with students ages 5 through 18 and is completed by the teacher. The ABI has a normative sample representative of all school-age children, including those with disabilities, and of a sample with mental retardation. The standardization sample was proportional in demographic characteristics to the 1980 census data. However, Smith (1989) notes that, at the low end of the normal intelligence norms, a few raw score points can dramatically change the adaptive behavior “quotient,” and suggests that the norms on students with mental retardation are more useful. An attempt was made to select items that would avoid ceiling effects for the normal population and to ensure basal measures for the population with mental retardation. There is evidence that the ABI has adequate construct, content, and criterion-related validity, as well as internal reliability, but no data were provided on interrater reliability. Smith (1989) cited many problems with the norm tables but concluded the ABI could contribute some information to the determination of mental retardation.

The Independent Living Scales (ILS—Loeb, 1996) were designed to assess the degree to which older adults are capable of caring for themselves (i.e., functional competence). It requires an individual to

demonstrate adaptive skills, rather than using a third-party informant or self-report to gather information on typical behavior. Reviews of the ILS have been generally negative, and it may not be suitable for disability determination purposes.

The Adaptive Behavior Evaluation Scale (ABES—McCarney, 1983) and the Parent Rating of Student Behavior (PRSB—McCarney, 1988) are used to identify mental retardation, learning disabilities, behavior disorders, vision or hearing impairments, and physical disabilities in students ages 5 to 21. Moran (2001) concluded that the information in the manual was not adequate to show how students with mental retardation differed from students with other disabilities. Norms are available to age 18 for the ABES and to age 12 for the parent scale. Reliability is good. High correlations with intelligence tests suggest it may be a duplication of this construct.

The Adaptive Behavior: Street Survival Skills Questionnaire (SSSQ—Linkenhoker & McCarron, 1983) was designed to assess adaptive behavior in youth from age 9 years and adults with mild to moderate mental retardation. The subscales are similar to general adaptive behavior scales, but there is a greater emphasis on skills required to function in community settings than on basic adaptive skills. It also differs from other adaptive behavior scales because it is administered as a test directly to the individual and, as such, does not measure typical performance in “real life.” Haring (1992) found this to be an advantage in terms of its excellent reliability but noted that there were concerns about validity. Another concern was whether one may obtain a comprehensive picture of overall adaptation to the natural environment, because some skills could not be tested using the SSSQ’s multiple-choice picture format. He suggested that the SSSQ could provide useful data when combined with the results of other comprehensive tests. To the extent that SSSQ data can predict entry or retention of competitive, gainful employment among people with mental retardation, it may have utility.

For the Social Skills and Vocational Success, Chadsey-Rusch (1992) described three measurement approaches to operationalize a

definition of social skills, including (1) the perception of others in the workplace, especially employers, (2) the goals and perceptions of the target individual, and (3) performance of social behaviors in natural contexts. Perceptions of others are typically measured by sociometric ratings and behavior rating scales. The Social Skills Rating System, described below, is a behavior rating scale that was developed to provide this information for students. Sociometric ratings provide useful information but are impractical for diagnostic purposes, and the use of nonstandardized rating forms is not recommended for diagnosis of significant limitations in social skills. Direct measures from target individuals involve presenting them with hypothetical situations and conducting direct observations. It is unclear whether individuals with low-normal intelligence or mild mental retardation would be able to respond reliably to hypothetical situations.

The Social Skills Rating Scales (SSRS—Gresham & Elliott, 1987) is probably the best measure available of social skills adaptation in the school context. Although developed for school-age children, this scale may hold promise for adapted use with adults in work settings. In addition to rating skill performance, raters also specify whether each skill is critical to success in the environment in which the child is observed, i.e., school or classroom.

Table 4-1 shows the principal available adaptive behavior measures that are comprehensive in nature and their characterstics, including age range for use, age range of norm groups, date of publication, available versions, examiner requirements, appropriate scores for use in determining presence of adaptive behavior limitations, and assessed reliability of scores.

ASSESSMENT ISSUES IN ELIGIBILITY DETERMINATION

Relation of Principal Adaptive Behavior Scale Content to SSA Criteria

In Chapter 1 we provided the details of SSA’s criteria for a disability determination of mental retardation in terms of both mental capac-

ity and adaptive functioning. Adaptive behavior measures are useful in the identification of limitations concurrent with an IQ significantly below average. They also have utility in documenting delays or functional limitations consistent with marked impairment in motor development, activities of daily living, communication, social functioning, or personal functioning. These measures also may be validly used, with repeated or periodic administrations, for assessment of changes in status. Generally, however, adaptive behavior measures will be less effective in fine-grained analysis and classification of such problems as specific motor disorders or communication disorders and deficiencies in concentration, persistence, or pace.

SSA guidelines further clarify the intent and nature of activities of daily living and social functioning for adults, and personal functioning for younger and older children, closely paraphrased below:

-

Activities of daily living include adaptive activities such as cleaning, shopping, cooking, taking public transportation, paying bills, maintaining a residence, caring appropriately for one’s grooming and hygiene, using telephones and directories, and using a post office, etc. In the context of the individual’s overall situation, the quality of these activities is judged by their independence, appropriateness, and effectiveness. It is necessary to define the extent to which the individual is capable of initiating and participating in activities independent of supervision or direction.

-

The number of activities that are restricted does not represent a “marked” limitation in activities of daily living, but rather the overall degree of restriction or combination of restrictions must be judged.

-

Social functioning refers to an individual’s capacity to interact appropriately and communicate effectively with others. Social functioning includes the ability to get along with others, e.g., family members, friends, neighbors, grocery clerks, landlords, and bus drivers. A history of altercations, evictions, firings, fear of strangers, avoidance of interpersonal relationships, or social isolation may demonstrate impaired social functioning. Strength in social functioning may be docu-

TABLE 4-1 Principal Comprehensive Adaptive Behavior Measures and Their Characteristics

|

Adaptive Behavior Measurea |

Age Range: Use |

Age Range: Norms |

Year Published |

|

AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale-Residential and Community |

18-79 years |

18.0 to 60+ years N = 4,103 people with DD |

1993 |

|

AAMR Adaptive Behavior Scale-School |

3-18 or 3-21 years |

3.0-18.11 years N = 2,074 students with MR; N = 1,254 students w/o MR |

1993 |

|

Adaptive Behavior Assessment System |

5-89 years |

5-21 years; N = 1,670 &1,690; general population 16-89 years; N = 920 & 990; general population |

2000 |

|

Versions |

Examiner Requirementsb |

Appropriate Scores |

Principal Reliabilities |

|

Children’s version (see below) |

Completion by a professional; or completion by a paraprofessional, with professional supervision (perhaps Class C, not specified) |

-Personal self-sufficiency -Community self-sufficiency -Personal-social responsibility & 10 domain scores |

Test-retest: (N = 45) -Factors: r = .93 to .98 -Domains: r = .88 to .99 Interrater: (N = 16) -Factors: r = .97 to .99 -Domains: r = .83 to .99 |

|

Adult version (see above) |

Completion by a professional; or completion by a paraprofessional, with professional supervision (perhaps Class C, not specified) |

-Personal self-sufficiency -Community self-sufficiency -Personal-social responsibility & 9 domain scores |

Test-retest: (N = 45) -Factors: r = .72 to .79 -Domains: r = .75 to .95 Interrater: (N = 15) -Factors: r = .98 to .99 -Domains: r = .95 to .99 |

|

-Parent form -Teacher form -Adult form |

Completion by a professional; or completion by a paraprofessional, with professional supervision (perhaps Class C, not specified) |

-Global Adaptive Composite (GAC) -10 Domains: communication; community use; functional academics; home/school living; health & safety; leisure; self-care; self-direction; social; work |

(Parent Form) Test-retest: (N = 102) -GAC: r = .96 -Domains: r = .83 to .94 Interrater: (N = 81) -GAC: r = .84 -Domains: r = .57 to .82 |

|

Adaptive Behavior Measurea |

Age Range: Use |

Age Range: Norms |

Year Published |

|

Comprehensive Test of Adaptive Behavior-Revised |

Birth-60+ years |

5-22 years; N = 2,094; students with MR 10-60+ years; N = 4,456; with MR 5-22 years: N = 4,525; students w/o MR |

2000 |

|

Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised |

3 months-90 years |

3 months-90 years; N = 2,182; general population |

1996 |

|

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scalesc |

1-99 years |

0.1 to 18.11 years N = 3,000 general population |

1984 |

|

Versions |

Examiner Requirementsb |

Appropriate Scores |

Principal Reliabilities |

|

-Normative Adaptive Behavior Checklist-Revised (NABC-R) is composed of a subset of CTAB-R items -Also a parent/guardian form of the CTAB-R |

Completion of NABC-R by a parent or guardian Completion by a professional; or completion by a paraprofessional, with professional supervision (perhaps Class C, not specified) |

-Total score -7 Domains: self-help; home living; independent living; social skills; sensory-motor; language/academics |

(School sample) Test-retest: (N = 58) -Total: r = .99 -Domains: r = .98 to .99 Interrater: (N = 32) -Total: r = .99 -Domains: r = .95 to .99 |

|

-Short form -Early development form -Other related instruments |

Completion by a professional; or completion by a paraprofessional, with professional supervision (possibly Class C for & interpretation of scores) |

-Broad Independence Score (BIS) -4 Cluster scores: motor skills; social interaction & communication skills; personal living skills; community living skills |

(Children w/o MR) Test-retest: (N = 31) -BIS: r = .98 -Clusters: r = .96-.97 Interrater: (N = 26) -BIS: r = .95 -Clusters: r = .88-.93 |

|

-Interview survey form -Expanded form -Classroom edition |

Class C; or completion by social worker or educator |

-AB composite -Communication -Daily living -Motor -Socialization |

(Interview survey form) Test-retest: (N = 484) -Composite r = .88 -Domains r = .81 to .86 Interrater: (N = 160) -Composite r = .74 -Domains r = .62-.78 |

-

mented by an individual’s ability to initiate social contacts with others, communicate clearly with others, interact, and actively participate in group activities. Cooperative behaviors, consideration for others, awareness of others’ feelings, and social maturity also need to be considered. Social functioning in work situations may involve interactions with the public, responding appropriately to persons in authority, e.g., supervisors, or cooperative behaviors involving coworkers.

-

A “marked” limitation is not represented by the number of areas in which social functioning is impaired, but rather by the overall degree of interference in a particular area or combination of areas of functioning.

-

Personal functioning in preschool children pertains to self-care, i.e., personal needs, health, and safety (feeding, dressing, toileting, bathing; maintaining personal hygiene, proper nutrition, sleep, health habits; adhering to medication or therapy regimens; following safety precautions). Development of self-care skills is measured in terms of the child’s increasing ability to help himself or herself and to cooperate with others in taking care of these needs. Impaired ability in this area is manifested by failure to develop such skills, failure to use them, or self-injurious actions. This function may be documented by a standardized test of adaptive behavior or by a careful description of the full range of self-care activities. These activities are often observed not only at home but also in preschool programs.

-

Personal functioning in adolescents pertains to self-care. It is measured in the same terms as for younger children, the focus, however, being on the adolescent’s ability to take care of his or her own personal needs, health, and safety without assistance. Impaired ability in this area is manifested by failure to take care of these needs or by self-injurious actions. This function may be documented by a standardized test of adaptive behavior or by careful descriptions of the full range of self-care activities.

The overall correspondence of several adaptive behavior measures to the content within the functional areas that are considered in ascertaining marked limitations is shown in Table 4-2. Each of the four adaptive behavior measures included in the table collects or assesses information regarding developmental status or performance in the areas of motor development, activities of daily living, communication, social functioning, and personal functioning. This table is a useful means to summarize and illustrate the detailed description of adaptive functioning that meets listing criteria, which are required to establish eligibility for SSI and DI.

Sensitivity of Scales at Ranges in Which Diagnostic Confirmation Is a Priority

Because adaptive behavior scales are targeted either specifically at children and adolescents or at groups ranging from children to young adults, there is a strong developmental component to their structures (Widaman et al., 1987). Such scales sample behaviors that are typically achieved at a range of ages and can indicate strengths and weaknesses in the ability to adapt. However, this also means that most scales are structured in steps that permit sampling of typical developmental tasks at each age. For any given age, it is unlikely that developmental tasks will be oversampled. In fact, as noted above, in the construction of adaptive behavior scales, such oversampling is typically avoided. Therefore, these instruments generally do not have firm cut-

TABLE 4-2 Correspondence Between SSI Classification Domains and Domains or Subdomains in Prominent Adaptive Behavior Measures

|

SSI Classification Domain |

AAMR–ABSa |

ABAS |

SIB-R |

VABS |

|

Motor development |

-Physical development |

-Health & safety |

-Motor skills (gross & fine) |

-Motor skills (gross & fine) |

|

Activities of daily living |

-Independent functioning -Domestic activity |

-Self-care -Home living |