1

Introduction

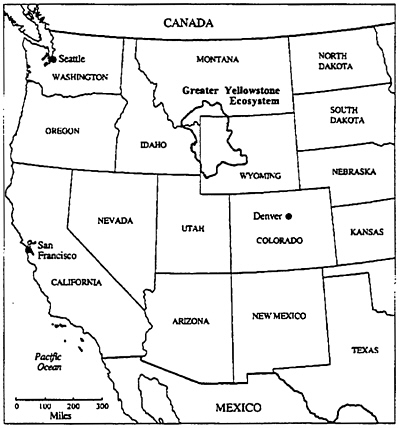

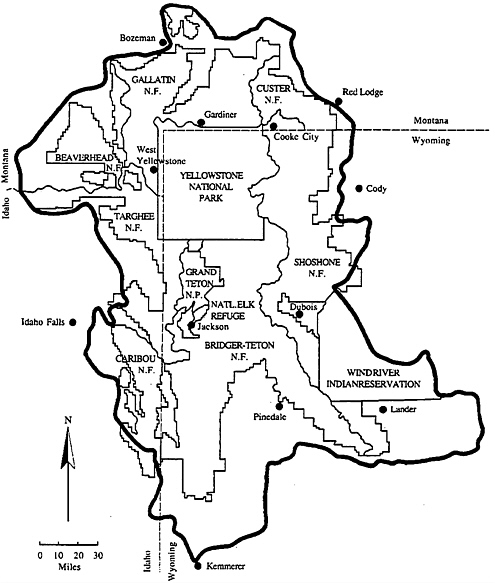

BACKGROUND AND CHARGE TO THE COMMITTEE

THE GREATER YELLOWSTONE ECOSYSTEM (GYE) is a large and rich temperate ecosystem (Figure 1–1). It includes six national forests, Yellowstone National Park (YNP), Grand Teton National Park, and two national wildlife refuges. It contains the largest functional geothermal basin in the world. More than 1,700 plant species have been identified in the GYE; 80% of the area is forested. Ten species of fish, 24 of amphibians and reptiles, more than 300 of birds, and 70 of mammals are present in the GYE in addition to thousands of invertebrate species. This rich and varied ecosystem supports diverse human activities; provides economic, recreational, educational, and aesthetic benefits; and has a growing resident human population. At the heart of the ecosystem is YNP—established as the world’s first national park in 1872, made a biosphere reserve in 1976, and added to the World Heritage List in 1978.

YNP, which encompasses 899,139 ha (8,991 km2), faces peculiar and complex management challenges. In the 128 years since YNP was established, a variety of management policies and strategies have been used to fulfill the park’s mission and its relationship to the American public’s desire for expanded tourism and recreational opportunities. The concurrent changes in societal values and attitudes toward the natural environment have complicated management of YNP over this time. Adding to the management challenges is the knowledge that management approaches implemented in YNP, the

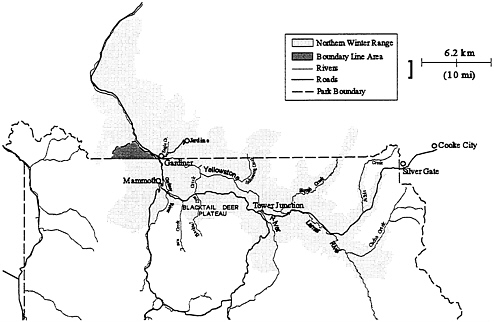

FIGURE 1–2 Yellowstone’s northern winter range. Source: YNP 1997.

nation’s premier park, influence management in other parks in this country, and throughout the world, as well as affect the economic bases of neighboring states, where wildlife viewing, recreation, and hunting are important. One of the most contentious approaches, applied since the late 1960s, is the policy of “natural regulation.” Concern has centered around the effects natural regulation might have on ecosystem processes, particularly in the northern winter range of ungulates of the GYE (Figure 1–2). Under natural regulation, ecological processes and physical influences—such as primary production, foraging, competition, weather, predation, and animal behavior—determine or limit population dynamics, rather than hunting and other human interventions.

Seven ungulate1 species are native to YNP: elk (Cervus elaphus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), bison (Bison bison), moose (Alces alces), bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), pronghorn (Antilocapra americana), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) are not native to the park, but their numbers are increasing from

introductions made outside YNP, particularly in the Absaroka, Gallatin, and Crazy Mountain ranges of Montana. All native large predators are present, including the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), black bear (Ursus americanus), coyote (Canis latrans), mountain lion (Felis concolor), and the reintroduced gray wolf (Canis lupus).

Ungulates that graze within YNP for much of the year often winter on the northern range in and adjacent to YNP. The northern range, a mixture of grassland and forest approximately 153,000 ha in area, encompasses lands along the Yellowstone River and Lamar River basins lower than 2,255 m from the junction of Calfee Creek and the Lamar River in the east to the area around Dome Mountain and Daly Lake in the west. Two-thirds of the northern winter range is within YNP; one-third is north of the park boundary on public and private lands (Houston 1982, Clark et al. 1999) (Figure 1–2). The pre-European winter range included the lowlands north of the park now devoted to agriculture, ranching, and rural residences.

Elk and bison populations have increased markedly during the past century, particularly in years with mild winters, leading some scientists to question the appropriateness of the park’s natural-regulation policy. Claims have been made that the northern winter range is overgrazed and that woody vegetation and riparian areas are being destroyed. Because they are the most abundant ungulate species, elk have been held primarily responsible for these effects. Elk commonly browse woody vegetation, such as aspen, cottonwood, and willow, especially in winter. The claim is that they have eliminated much of the riparian-zone woody vegetation and are preventing generation of aspen and cottonwood stands, thereby reducing food sources for other species, such as beavers, moose, deer, and grizzly bears. Stream degradation and serious erosion have also been attributed to overgrazing by elk and bison. The spread of diseases, especially brucellosis, among dense populations also is a concern. However, other scientists claim that ungulates have influenced vegetation on the northern range for thousands of years when natural density-dependent factors such as forage availability, predation, and disease regulated population dynamics and that current effects fall within the natural range of variability.

Because the controversy over natural regulation has heightened recently, in the 1998 appropriations to the U.S. Department of the Interior, Congress (the House Appropriations Committee report) stated: “A number of scientists question the natural regulation management program conducted by Yellowstone National Park as it relates to bison and elk, while others defend the approach. The Committee wishes to resolve the issue of population dynamics of the northern elk herd as well as the bison herd. The Committee thus directs

the [National Park] Service to initiate a National Academy of Sciences (Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology) review of all available science related to the management of ungulates and the ecological effects of ungulates on the range land of Yellowstone National Park and to provide recommendations for implementation by the Service” (HR Report 105–163; appropriations in 105–83).

In response to that mandate, the National Research Council convened the Committee on Ungulate Management in Yellowstone National Park. The committee is composed of experts with backgrounds in ungulate ecology, wildlife biology, animal/veterinary science, animal population modeling, grassland ecology, riparian ecology, climatology, hydrology and geomorphology, landscape ecology, and soil science. These experts were charged to review the scientific literature and other information related to ungulate populations on the Yellowstone northern range, particularly as they relate to natural regulation and the ecological effects of elk and bison populations on the landscape. Much of YNP is not noticeably affected by current management practices. The northern range, however, where Yellowstone’s elk herds spend the winter, is the origin of much controversy, and the geographic focus of this study. The following specific scientific questions were addressed within the context of the park’s goals:

-

What are the current population dynamics of ungulates on the northern range of the GYE?

-

To what extent do density-dependent and density-independent factors determine average densities and fluctuations in populations of YNP ungulates?

-

What are the consequences of continuing the current natural regulation practices (e.g., on range condition, habitat for other species, risk of disease transmission)?

-

How do current ungulate population dynamics and range conditions compare with historical status and trends in those processes?

-

How do current ungulate population dynamics in the GYE compare with other North American grasslands and savanna ecosystems that still have native large predators?

-

What are the implications and limitations for other natural regulation practices applied to other biota?

-

What gaps and deficiencies in scientific knowledge should future research attempt to address?

During its analyses, the committee identified other topics relevant to its charge

and important to evaluating the consequences of current ungulate management strategies in YNP.

The committee met four times over the course of its deliberations. Meetings were held in Gardiner, Montana, and in Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming, to permit committee members to see the northern range in summer and winter and to obtain input from federal and state agency personnel and members of the public who are intimately familiar with the issues. The committee is aware of the deeply held convictions of many different parties and the difficulties faced by land and animal managers in the GYE. This consensus report presents the committee’s scientific evaluations of the issues it was asked to address. The committee recognizes that these evaluations are only part of a multifaceted problem that includes sociological, economic, and other important dimensions that it was not asked to evaluate.

NATURAL REGULATION

Natural regulation is the current National Park Service (NPS) policy for management of ungulates and other ecosystem components within YNP. As currently practiced, natural regulation means simply “free of direct human manipulation.” The intent is to allow the biological and physical processes within the park to function without human influence. Implementation of the policy includes letting wildfires burn freely and prohibiting hunting within the park. However, NPS has other policy mandates within YNP that might not be consistent with natural regulation. For example, the National Park Organic Act of 1916 prescribes that “[t]he fundamental purposes of said parks is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such a manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” It is of course not possible to construct and maintain a road system within the park, with associated public facilities and services, “to provide for the enjoyment” of the three million visitors who currently visit the park annually, without affecting the scenery, vegetation, and animal life.

A more realistic definition of natural regulation as practiced by NPS in YNP is that it attempts to minimize human effects on the natural systems of the park. The National Park Service 1988 Management Policies describes the management strategy as “natural environments evolving through natural processes minimally influenced by human actions.” Under this policy, some

interventions have been allowed. For example, to restore natural predation processes, wolves were reintroduced. To gain a better understanding of ungulate ecology in the park, there has been some manipulation of animals and vegetation through live capture, the equipping of animals with radio transmitters, and the use of fenced enclosures to assess plant growth in the absence of grazing and browsing. Research is also undertaken to satisfy NPS mandates to better facilitate management of visitors to the park, to minimize their impact on wildlife and vegetation, and to enhance public enjoyment by providing interpretive information about the ecology of the park. Where these mandates conflict with preservation of natural environments and processes, conservation is considered the park’s primary responsibility (NPS 2001).

NPS also influences the behavior and movement patterns of ungulates and their predators through control and routing of park visitors in both summer and winter. YNP biologists and managers participate in the Northern Yellowstone Cooperative Wildlife Working Group, which includes NPS; Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks; Gallatin National Forest; and the Biological Resources Division of the U.S. Geological Survey. They also provide advice and make recommendations in the development of management policy for YNP ungulates when they are outside of the park, where human interventions are more pervasive.

Although YNP’s natural regulation policy attempts to minimize human intervention within the park, this does not characterize the policies that affect ungulates when they are outside the park. In other words, YNP is an ecological island whose processes are influenced by human activities in the surrounding area. These activities, which strongly influence YNP wildlife, include agriculture, ranching, and hunting. Thus, even if there were no human intervention within YNP, ecological processes there would be profoundly influenced by human activities elsewhere. In this sense, management can, at most, be only partly natural.

What Is Natural?

Climate displays a great deal of variability, even over the ecologically short period of 100 to 200 years. Other ecological processes also fluctuate with time but fluctuations may fall outside natural variability if driving factors create extraordinary responses. The limits of variability of an ecosystem process or component can be known only if those attributes have been examined with

appropriate tools using long-term analyses. This has not been the case for YNP. How, then, can a reasonable standard be found to indicate what range of conditions on YNP’s northern range is natural? The historical sequence of interacting biotic, environmental, and anthropogenic factors is unrepeatable, which makes it difficult to identify “natural baseline conditions” (Anderson 1991, Patten 1991). It follows, therefore, that if the natural regulation policy assumes that all processes under the policy are functioning in a natural fashion, any outcome of the policy would also have to be termed natural. However, our lack of understanding about previous conditions and current dynamics makes it difficult to reject either the hypothesis that ungulate populations will be naturally regulated without causing long-term damage to the GYE or the notion that naturally regulated ungulate populations will cause long-term damage to the GYE. Outcomes may indeed be natural, but their desirability is a question of values beyond this committee’s scientifically circumscribed task.

Some Implications of a Natural Regulation Policy

The national park system comprises many diverse parks, ranging from vast expanses of near-wilderness, like YNP, to small urban gardens, such as Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens in Washington, D.C. No single management policy is appropriate for this diverse array of parks.

A natural-regulation policy is motivated in part by the belief that national parks should contain natural ecosystems. However, even the largest of them is only a fragment of the predevelopment ecosystem, and none has been unaffected by human activity. So the “natural” in “natural regulation” can never be absolute, and debates about what interventions are appropriate will inevitably accompany all management decisions. Pritchard (1999) described the issue well: “A rock-solid definition of what is natural will elude us, because that question is wrapped up in our cultural attitudes about our place in nature. In an age when science recognizes the role of change and disturbance in the landscape, discussion will shift from ‘how do we restore nature’s balance?’ to consideration of how much change we are willing to allow in our parks. Given the shrinking size of naturally forested areas and continually growing human disturbances in the region, however, landscape changes may bump into other conservation goals, namely the preservation of threatened species.”

The belief that national parks should harbor natural ecosystems has

fostered extensive debates about whether observed changes in the parks are caused by humans. If they are, natural management would require intervention to reduce, if possible, human-caused changes. If they are not, intervention would be inappropriate. The problem is aggravated by changes in the perception of the role of humans in nature, from acceptance that Native Americans were part of the GYE in the past to today’s viewpoint in our highly urbanized society that humans exist outside of nature. The problem, as described by Pritchard, is to distinguish between natural and human-caused changes. Disagreements about this issue are at the heart of controversies over management of YNP. For example, critics of YNP maintain that human influences on elk populations, and on their predators, have led to overgrazing. Thus, overgrazing represents a human impairment and should be managed. In contrast, YNP maintains that changed climate is a major driver and that the ecological changes are natural. As Schullery (1997) put it, “[W]e have imagined ourselves wise enough to control [Yellowstone National Park] and have rushed to judge what is wrong with it. And every time we looked hard enough, we discovered that there was more wrong with our judgment than with Yellowstone.”

Although such debates in part may be stimulated by the value-laden word “natural regulation,” describing management strategies by different words will not cause the debates to disappear. Controversy will continue, because, fundamentally, the debates are not about the words but rather about the roles people want the parks to play.

Policy Versus Practice

The distinction between policy and practice is subtle and ill defined; however, an understanding of the distinction as applied in YNP is important for understanding the controversy about ungulate management in YNP and for evaluating management options. A policy is “a definite course or method of action selected from among alternatives and in light of given conditions to guide and determine present and future decisions,” whereas a practice is much less formal or rigid, being “actual performance or application, a repeated or customary action, [or] the usual way of doing something” (Merriam-Webster 1993).

Natural regulation as a policy for YNP (Schullery 1997, YNP 1997, Pritchard 1999) implies that if a change in the ecosystem is natural, then

management intervention is inappropriate. On the other hand, if a change is due to a management policy implemented by the park, then there is justification for repair or restoration of that change or impairment. This has led to distracting and ultimately unproductive arguments about whether high elk populations and low aspen recruitment in the northern range are the effects of natural changes (e.g., climate) or human actions (e.g., removal of predators). Under a policy of natural regulation, such an argument is important, because the appropriateness of the park’s management actions (or lack of them) depends on whether they are consistent with the policy. If natural regulation were only a practice, the debates could focus on the actions and their outcomes. In addition, adaptive management might be easier to undertake.

The committee believes that a better way to approach these issues is to focus on objectively measured processes, numbers, and events and how intervention might alter them rather than to debate what is or is not natural. Thus, this committee has tried to assess whether current ecosystem conditions are outside the range of what might be expected in similar ecosystems elsewhere or might have been expected in this ecosystem over the past few millennia. The committee has also tried to assess whether current conditions are likely to lead to a substantial and rapid change in any major ecosystem component or process.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The current policy for management of YNP has been influenced by the history of the region, the park’s establishment, previous park management, and the public’s goals for the park (Schullery 1997, Pritchard 1999). One ongoing debate focuses on whether the “natural” in natural regulation includes humans as part of nature. Most writing on the subject relative to North America has included aboriginal people and their activities before contact with Europeans (Callicott 1982). But historical and archeological evidence suggests that Native American cultures and their effects on the environment have been in a dynamic state of flux marked by periods of change and intervals of stasis since the first humans arrived from Asia (Guthrie 1971). In the Great Basin and adjacent Rocky Mountain region, human cultures were based on hunting and gathering, but during the century before direct contact with Europeans, major changes in aboriginal peoples’ distribution, numbers, and cultural relationships to the environment followed acquisition of the horse (an indirect product of European contact). Thus, whether we view humans as part of

nature, we still must acknowledge that humans have, since their arrival in the area, been agents of change.

In addition to human-caused changes, the ecology of YNP has been profoundly influenced by changes in the physical environment. Of these, climate change has been the most important driving factor during the past 10,000 years. Climate models developed by scientists project major climate changes for the future, some of them caused by human activity (NRC 2001). Climate changes complicate management strategies because they make it especially difficult to predict the likely consequences of any human interventions as well as the consequences of not intervening.

Biodiversity Context

Yellowstone’s wildlife, including its ungulates, is part of a diverse biota. YNP is estimated to have 1,700 species of native vascular plants, 170 exotic plant species, 186 species of lichens, 59 mammal species, 311 species of birds, 18 fish species, 6 species of reptile, 4 amphibian species, and an unknown number of organisms associated with hot springs, to say nothing of insects, invertebrates, fungi, and bacteria (YNP 2001). The GYE contains even more species. In addition, YNP is home to several threatened (grizzly bear, Canada lynx, and bald eagle) and endangered (peregrine falcon, timber wolf, and whooping crane) species.

Biodiversity is a dynamic ecosystem characteristic that may fluctuate naturally or in response to human activity (Noss and Cooperrider 1994). Altered community structures, and processes including those resulting from human activities and management practices (Weins and Rotenberry 1981, Rothstein 1994, Hansen and Rotella 1999), may change species composition and prevalence (Hansen and Urban 1992), but how they have done so in the GYE is poorly understood. Changes caused by changes in population dynamics of ungulates may affect not only dominant landscape features, such as aspen or sagebrush, but also vast numbers of associated organisms.

A Brief History of Park Management

At least 28 federal, state, and local entities manage various activities in the GYE, sometimes with conflicting goals. Within YNP, management policies generally have been based on the prevailing understanding of wildlife biology

and ecology. When the park was established in 1872, ungulates were fed and given protection from hunting and predators because they were considered the species visitors desired to view. Most predators were reduced, and wolves were extirpated from the area. Wolves were restored in 1995; about 160 are present in the GYE, 50 of which are on the northern range. From the 1930s through the late 1960s, NPS shot and trapped elk to reduce the population to what was considered a sustainable level for the northern range (Houston 1982). By the late 1960s, the elk population on the northern range had been reduced from some 10,000 animals to fewer than 5,000. Unfavorable reactions to NPS control measures from a variety of public interests led to Senate hearings. YNP then adopted natural regulation practices because they had no other management alternative (Pritchard 1999). The most recent northern range elk count observed 13,400 individuals (T.Lemke, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, personal communication, June 13, 2001). Some 120,000 elk are present in the GYE. Roughly 2,500 free-ranging bison also are present in YNP.

Aldo Leopold (1933), in his classic Game Management, which laid the foundation for modern wildlife management, acknowledged that wildlife management was essentially management of human behavior toward the land that harbored wildlife and toward the wildlife through harvest by hunting and trapping. To quote Leopold, “…game management produces a crop by controlling the environmental factors which hold down natural increase, or productivity, of the seed stock” (Leopold 1933). Management of wildlife within YNP, or more correctly management of human behavior that affects wildlife within YNP, has been driven by the view that national parks exist for public enjoyment and appreciation. Thus, wildlife within YNP has been managed to achieve certain objectives for human interactions with wildlife, although recent management philosophy tends toward ecosystem management. To enhance human contact with wildlife, roads, trails, campgrounds, and other park facilities have been constructed. Those actions have altered habitats upon which wildlife depends and have influenced the movement, location, and concentration of people, which further alters the distribution of wildlife.

YNP was established in 1872, more than 60 years before Leopold provided the conceptual basis for modern wildlife management. Efforts to manage wildlife in Yellowstone in the past and present must therefore be viewed within the context of those times (Table 1–1). Market hunting of ungulates and killing of carnivores were common in the area before and continued after the park was established. In 1883, public hunting within the park was prohibited, but no effective enforcement occurred until the U.S. Calvary was assigned in

TABLE 1–1 Chronology of Significant Events in Yellowstone National Park’s History

|

Year/Period |

Event |

|

1860s |

Period of extensive fires (Romme and Despain 1989) |

|

Before 1870 |

Evidence of substantial elk use of the northern range, at least in summer (Houston 1982) |

|

1872 |

Yellowstone National Park declared first national park (organic act) |

|

1869–1883 |

Extensive market hunting; ungulates and carnivores greatly reduced (YNP1997) |

|

1883 |

Public hunting within YNP prohibited (YNP 1997) |

|

1886 |

U.S. Calvary assigned to protect the park; beginning of effective control of hunting (Houston 1982, YNP 1997) |

|

1894 |

Lacey Act enacted, prohibiting all hunting and killing of wildlife except dangerous animals (Schullery 1997) |

|

1900–1935 |

Intensive control of predators; wolves extirpated (YNP 1997) |

|

1902 |

Few bison remained in YNP; population supplemented from domestic bison herds (Meagher 1973) |

|

1917 |

Brucellosis detected in YNP bison (Mohler 1917) |

|

1918 |

U.S. National Park Service assumed control of YNP (YNP 1997) |

|

1920s |

“Too many elk in park”; active management to control population. Increasing concern about overgrazing (YNP 1997) |

|

1920s |

Reported decline in white-tailed deer population from about 100 to few or none (Skinner 1929) |

|

1920–1960 |

Commercial definition of over-grazing applied to YNP; intensive population control of elk and bison (YNP 1997) |

|

1923–1929 |

Elk removed primarily by hunting outside park; probably 10–15,000 elk on northern range (Houston 1982) |

|

1930s-present |

Very little recruitment of aspen on the northern range |

|

1960s |

Period of most intensive elk population control and population reduction (YNP 1997) |

|

1963 |

Leopold report published (Leopold et al. 1963) |

|

1968 |

YNP adopts policy of “natural regulation”; intensive regulation of elk and bison ends (Cole 1971) |

|

1969–1981 |

Period of rapid increase in elk population from ~4,000 to ~16,000 (Houston 1982) |

|

1969–1995 |

Bison population expands from ~400 to ~4,000 (YNP 1997) |

|

1986 |

Congress funds study of “overgrazing” in the northern range |

|

1988 |

Extensive fires in YNP |

|

1988–1989 |

Severe winter reduces elk and bison populations |

|

1995 |

Reintroduction of wolves |

|

1996–1997 |

Severe winter; slaughter of #DXGT#1,000 bison as they left YNP |

1886 to protect the park. Public attitudes toward wildlife at the time were mixed (Magoc 1999). With the rapid expansion of domestic livestock onto western range lands, many viewed wild ungulates as competitors for forage. Others appreciated them for their meat and hides. The decline of wild ungulates in the Yellowstone area by the end of the nineteenth century resulted largely from market hunting (Krech 1999). Construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad into the region north of the park in 1883 expanded access to markets for meat and hides. Concern about the decline of wild ungulates developed among residents in the area as well as in eastern states where an embryonic national conservation movement was emerging. At that time large carnivores were viewed as undesirable by most of the public, because they killed both domestic livestock and wild ungulates and were feared to pose a threat to humans. As a reflection of this public sentiment, although other wildlife species were protected within the park, control of predators by park managers began in the nineteenth century and became intensive between 1900 and 1935, resulting in the extirpation of wolves and probably mountain lions.

Few bison remained in Yellowstone by the end of the nineteenth century, and the population was supplemented from domestic herds in 1902 (Meagher 1973). The Yellowstone bison herd had become the only free-ranging herd in the United States, and thus, the YNP played a key role in restoring bison in the wild and removing the threat of their extinction that existed by the late 1800s. Intensive management of bison within the park was the practice until the NPS announced in 1968 a policy of natural regulation of wildlife populations. Management included an early period of annual roundups with selective slaughter, maintaining an irrigated hay field in the Lamar Valley for winter feeding, capturing and shipping animals outside of the park, and, from the 1920s into the late 1960s, harvests to prevent overgrazing on the winter range (Pritchard 1999). Concern about the spread of brucellosis, carried by bison, to domestic livestock outside of the park led to the slaughter of more than 1,000 bison as they left the park during the extreme winter of 1996–1997 (Peacock 1997).

In the twentieth century, although not as intensively managed as bison, elk in Yellowstone were periodically fed in winter and were subjected to population reductions through shooting, corralling, and translocation until the winter of 1968–1969, a year after the adoption of natural regulation (Pritchard 1999). Hunting of Yellowstone elk that leave the park in winter has continued throughout the history of the park. Other ungulates present in the northern

portions of YNP—mule and white-tailed deer, moose, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats—have not been the focus of restoration efforts or population reduction efforts in response to concerns about overgrazing.

In the early history of the park, the public and park managers thought that wolves, mountain lions, and coyotes threatened the well-being of the park ungulates. The ungulates, because of their attractiveness to park visitors and the opportunities that existed to observe them, were considered a primary justification for the park’s existence and thus were the focus of management efforts. Interestingly, bears, which were considered a threat to human interests outside of the park, were appreciated by park visitors, who were allowed to view them at garbage feeding sites until the practice was discontinued in 1943 (Pritchard 1999).

By the middle of the twentieth century, there was a broadening appreciation for wildlife among the public along with an increased understanding of the interrelationships of wildlife in nature. This increased interest in wildlife led to recognition of the importance of natural environments for wildlife as well as their importance in providing ecologically rich environments for Americans to appreciate nature through leisure travel and other outdoor activities.

Changes in management of wildlife in YNP since its establishment reflect the changes in attitudes toward wildlife that have taken place among the American public. Several research efforts aimed at increasing understanding of the ecology of ungulates and carnivores within the park were initiated in the post-World War II years, although many studies occurred earlier and are cited in several sections of this report. Two studies worthy of note were by the Muries. In the 1930s Adolph Murie (1940) completed a detailed study of the diets of coyotes in the park, and his brother, Olaus Murie (1951), studied elk foraging ecology in the Jackson Hole area south of the park. Research findings by the Muries and other researchers who followed them, although preliminary and often controversial (Leopold et al. 1963, Schullery 1997), disclosed some of the complexity of the ecological relationships of bears and coyotes as well as of the ungulates in the park. Large predators had finally gained appreciation in the eyes of both the public and the park managers. They were protected with the intent to restore them as valued components of the park wildlife. However, the NPS did little to encourage continued research toward understanding the complexity of predator-prey relationships or the details of the functioning of park ecosystems (Pritchard 1999). As a consequence of carnivore protection in the park, NPS came under increased pres-

sure from ranchers outside of the park who were losing livestock to coyotes, bears, and mountain lions that were leaving the park as their populations increased.

In 1967, NPS Director Hartzog, along with Secretary of the Interior Udall and Senator McGee of Wyoming made a decision to stop killing elk in YNP. Hartzog announced that the most desirable means of controlling the elk numbers was through public hunting outside the park. According to Sellars (1997), this policy decision to use “natural regulation” for management of wildlife “came not as the result of scientific findings, but because of political pressure.” Whereas Cole’s account (1969) represents natural regulation as simply a research hypothesis. This was essentially a “hands off” policy that abolished direct manipulation of wildlife or their habitats except to repair or reduce damage caused by human activities (Schullery 1997), although early elk management practices under this policy still allowed trapping and transport of elk (Sellars 1997). Recently, some intervention has been considered appropriate, including reintroducing wolves to the park to reestablish their role as a major predator of ungulates. Criticism of natural regulation policy and its perceived consequences resulted in the establishment of this committee and this report.

CLIMATE VERSUS ELK AS CAUSALITY OF CHANGES IN ASPEN AND WILLOW

The controversy over the status of aspen and willow within the northern range (often considered indicators of ecosystem condition) and natural regulation practice often revolves around conflicting statements about what factors most strongly influence the conditions currently found in the northern range. Supporters of natural regulation policy believe that current range conditions are determined primarily by biophysical factors, climate in particular, and that ungulate populations are having a small effect on range condition. Others believe that ungulate populations play a central role in determining range condition and that those populations are now so large that damage to vegetation on Yellowstone’s northern range has occurred. As an example, the impact of elk on streamside willows is a central issue in the controversy. However, willow communities are inextricably linked to climate, geology, surrounding vegetation, and fire history as well as to shorter-term and local impacts from ungulates and beavers, which makes the issue hard to resolve.

Several people who made presentations to the committee compared the condition of the northern range unfavorably with that on nearby ranches. Such comparison, however, reflects a confusion of values. Ranching seeks to maximize production for human use, whereas YNP seeks to preserve natural ecological processes. For example, within YNP, aspen is an important landscape element—it is an aesthetically pleasing tree that grows in groves on the hillsides and shows spectacular fall colors. It also is important as habitat for a diversity of bird species (Mueggler 1988, Pojar 1995). Willow, by comparison, is a rather plain plant that most lay visitors to YNP do not notice or might consider an ordinary “bush” if they did. Nevertheless, willow communities may prevent stream-bank erosion and subsequent changes in stream-channel morphology and are a food source for browsers and habitat for many other riparian species. Critics of the park’s natural regulation policy particularly emphasize the adverse effects of elk on streamside willows, which they maintain are excessive and are leading to erosion of northern range streams (Kay 1990, Chadde and Kay 1991).

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

To present a perspective for understanding current conditions in YNP, Chapter 2 describes historical conditions in the GYE, including climate, geological, and landscape conditions. Chapters 3 and 4 give an ecological context in which park management strategies are conducted, including a review of vegetation, possible driving factors, and processes related to ungulate population dynamics. Chapter 5 is a synthesis chapter that reviews overarching questions related to the problem at hand, and it presents the committee’s conclusions and recommendations.