6

Challenges in Adult Education

The discussion during the workshop highlighted a number of key challenges that must be addressed when performance assessments are used for accountability in the federal adult education system: (1) defining the domain of knowledge, skills, and abilities in a field where there is no single definition of the domain; (2) using performance assessments for multiple purposes and different audiences; (3) having the fiscal resources required for assessment development, training, implementation, and maintenance when the federal and state monies under the Workforce Investment Act (WIA) of 1998 are limited for such activities; (4) having sufficient time for assessment and learning opportunities given the structure of adult education programs and students’ limited participation; and (5) developing the expertise needed for assessment development, implementation, and maintenance. This chapter discusses these challenges and their implications for alternatives identified by workshop presenters.

DEFINING A COMMON DOMAIN OF KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS, AND ABILITIES

Varied Frameworks

One very critical stage in the development of performance assessments is defining the domain of knowledge, skills, and abilities that students will be expected to demonstrate. In her remarks, Mari Pearlman said that in

order to have reliable and valid assessments to compare students’ outcomes across classes, programs, and states, a common domain must be used as the basis for the assessment. This poses a challenge to the field of adult education because, as several speakers pointed out, there is no consensus on the content to be assessed. As Ron Pugsley, Office of Vocational and Adult Education of the Department of Education (DOEd), reminded participants, Title II of the WIA specifies the core measures that states must use in reporting student progress (see Table 2-1), but the content underlying these measures is not operationally defined in the same way by the states and sometimes not even by all the programs within a state. In many testing programs, there is a document (called a framework) that provides a detailed outline of the content and skills to be assessed. But on the national level, no such document exists for adult education, and few states have defined the universe of content for their adult basic education programs. Hence, the extent to which specific literacy and numeracy skills are taught in a program can vary greatly depending on the characteristics of the student population and available staff.

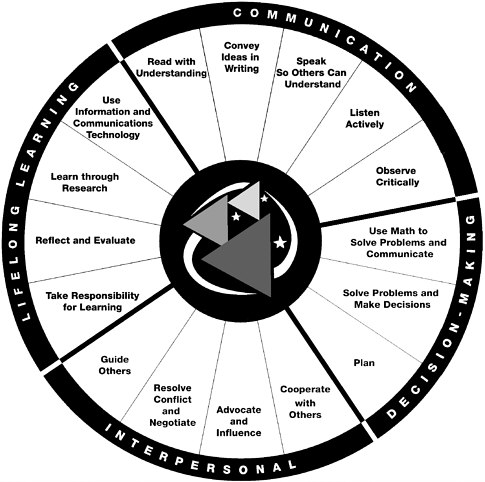

To address this variation in instructional content, the National Institute for Literacy (NIFL) began the Equipped for the Future (EFF) initiative in 1993. Sondra Stein explained that NIFL used the results of its survey of 1,500 adults to identify the themes of family, community, work, and lifelong learning as the main purposes for which adults enroll in adult basic education programs (see Figure 6-1 for the EFF standards). NIFL then specified content standards for each theme and is now in the process of developing performance assessments aligned with the content standards. Some states (Maine, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Washington) have adopted the EFF framework and are working with NIFL in the assessment development process, while others are in the process of developing their own assessments. Although EFF represents an important movement toward common content for adult basic education programs, not all states have adopted its framework at this time.

Comparability of Performance Assessments

As discussed in Chapter 5, workshop presenters described two approaches for identifying performance assessment tasks: the critical indicator approach and the domain sampling approach. Both approaches require delineation of the domain. In order for results from one version of the assessment to be comparable to results from another version, there needs to

FIGURE 6-1 EFF Standards for Adult Literacy and Lifelong Learning

SOURCE: NIFL, 2002.

be a common domain with agreed-upon critical skills and knowledge and types of tasks that allow students to demonstrate these skills and knowledge. While these two approaches may be feasible on a limited level, such as in a program or within a state, it will be much more difficult to apply them across states or nationally.

USING PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENTS FOR MULTIPLE PURPOSES

Throughout the workshop, participants enumerated the varied uses for assessments in adult basic education: for diagnostic purposes, to meet

accountability requirements, to provide feedback to students and/or teachers, and for program evaluation. As Pamela Moss explained, different purposes bring different kinds of validity issues, and David Thissen, Stephen Dunbar, and Jim Impara noted that it is difficult, if not impossible to develop one assessment that adequately serves such varied purposes. However, several speakers talked about ways performance assessments might be developed to serve the purpose of the NRS (National Reporting System). As suggested by Mark Reckase, Mari Pearlman, and others, the structured portfolio has the potential of serving the dual purposes of meeting accountability requirements and providing feedback to students. But for it to do so, the menu of content and tasks must be broad enough to meet the accountability requirements for the domain and to have enough examples to provide meaningful feedback to students.

Computer-based assessment could also serve the two purposes, and it has the advantage of providing rapid feedback to the student. According to Bob Bickerton and Donna Miller-Parker, use of computer-based assessment in adult basic education has been limited because of accessibility issues, costs, and training of staff. Henry Braun cautioned that it would be important to determine the types of learners for whom this modality would be appropriate before initiating its use for accountability purposes.

One factor that will need to be considered when performance assessments are used for accountability is the process of calibrating the performance assessments to the scale used for the NRS. Wendy Yen and Braun emphasized that a true calibration requires that the assessments be based on the same domains. While the developers of the tests with benchmark scores specified in the NRS attempted to calibrate their tests to the levels in ABE or ESL (depending on the test), various workshop presenters said that the calibration process was not technically accurate. Yen observed that these tests “have different content and have been developed under different criteria.” She said that these conditions are not sufficient for the more stringent linking procedures such as equating or calibration. These linking procedures require equivalence of test content and examination of item and test statistics, among other things. Yen also noted that several National Research Council (NRC) reports, such as Uncommon Measures: Equivalence and Linkage Among Educational Tests (1999c) and Embedding Questions: The Pursuit of a Common Measure in Uncommon Tests (1999a), have addressed the issue of linking results from different assessments. She observed that linking issues will need to be addressed when performance assessments are used to measure students’ movement on the NRS levels. She

cautioned that in order for multiple performance assessments to be developed and calibrated to the NRS, they would need to measure the same domains. If they do not, then the less rigorous process of social moderation could be used to ascertain the match between scores on the assessments and the NRS levels. However, several workshop participants questioned whether social moderation was sufficiently rigorous for use in a high-stakes environment.

HAVING THE REQUIRED FISCAL RESOURCES

Assessment Development and Staff Training

As described in Chapter 2, states have limited funding to spend on assessment development, staff training, implementation, and maintenance. Several presenters emphasized both the importance of having adequate development and training processes to support the creation of quality performance assessments, and the substantial cost of these activities. In his presentation, Reckase estimated that the cost for development of a performance assessment system could total $1.5 to $2 million.

Some of the expenses are one-time costs and some recur with each administration. One-time costs are those associated with initial implementation of the assessment. Recurring costs are the expenses for ongoing item or task development, administering the test, and scoring examinees’ responses. As mentioned earlier in this report, the cost for scoring responses to performance assessments or constructed-response questions is substantially higher than that for scoring selected-response questions. In addition, costs for the development of these assessments can be higher. Tasks used on performance assessments are easily memorized and, unlike selected-response items, often cannot be reused. Administration costs can also be hefty, given the time, materials, and resources required to administer performance assessments.

Eduardo Cascallar estimated that a performance assessment of language ability that he developed cost $120 per administration. Judy Alamprese noted that the current cost for an external degree program is approximately $2,000 per student, and Mark Moody stated that it is approximately $60 per student (for 180,000 students) for Maryland’s MSPAP, and this amount doesn’t cover the cost of test administration. States’ Leadership funding under WIA, which has ranged from $100,000 to $7.5 million per state per year (with most states at the lower end of this range), provides the money

states use for development and training activities. Because the federal allotment is the sole funding for these activities for most states, it is unlikely that individual states can afford substantial costs for implementing a performance assessment program. In light of this, workshop presenters suggested other options, such as the formation of consortia in which states work together or in conjunction with publishers to develop and score performance assessments. These ideas are further discussed in Chapter 7. However, the challenge to fiscal resources also extends to the administration of these assessments, especially when the national average expenditure per student in adult education programs is $374, and the 10 states with the lowest expenditures averaged only $156 per student (program year 1999).

Assessment Implementation and Maintenance

The creation of performance assessments, including specifying content domains and developing scoring rubrics as well as providing staff training, is only a portion of the cost of using these assessments. Implementing a performance assessment system and maintaining and refurbishing assessments are ongoing costs that programs must take into consideration. John Comings estimated that adult education programs could afford to spend only about $50 per student for assessment; this is inadequate for implementing a performance assessment system, according to Richard Hill, Impara, Reckase, and other speakers, given the experience of the National External Diploma Program in adult education or the K-12 system. While the presenters pointed out that there were cost differences in using the various alternative approaches to performance assessment that were suggested, none of the other assessments would cost as little as $50 per student.

Cascallar and other speakers observed that, in addition to implementation costs, there are costs associated with updating and revisions, particularly if the assessment is to meet the desire of many program staffs to have assessments that are dynamic. These updates include new development to keep the assessment current, refining scoring rubrics (particularly in the use of structured portfolios), and updating training manuals. The costs for these activities would need to be subsidized by the states or budgeted as part of the ABE programs’ operational costs. In addition, there are costs associated with training staff to administer performance assessments and providing the necessary materials and other resources. A final but important cost is associated with external review of the assessments

and the system. Under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the federal government has taken the lead in the evaluation of K-12 assessment systems. (Massachusetts is one of many states that also hire external reviewers.) Kit Viator emphasized the value of external review, commenting that it is important to let others have access to materials and come to their own independent conclusions about the strengths and weaknesses of the program.

HAVING SUFFICIENT TIME FOR ASSESSMENT AND LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES

Time is one aspect of the adult basic education service delivery system that poses significant challenges for the use of performance assessment. Time is a limited commodity for most adult education students. As mentioned in the overview and by a number of presenters, adult education students spend a limited amount of time in instruction, and they have limited time for carrying out performance assessments. Speakers queried whether this amount of time provided a sufficient “opportunity to learn.” If the instructional time is not sufficient for learning, then the assessment may not be a reliable test of students’ educational progress. The speakers noted that student persistence in regularly attending classes and completing a course of study is a critical factor for most adult education programs. Lack of student persistence appears to be a characteristic of the system that is unaffected by attempts to remedy it.

In suggesting alternative ways to construct performance assessments, Reckase described the challenge of addressing the “information channel” in which the goal is to assess as much skill and knowledge as possible within a specified amount of time. As stated earlier, Reckase estimated that 50 to 100 selected-response items can be administered to an adult in an hour, while no more than 10 performance assessments can be given in the same period of time. With the current levels of student persistence, students’ patterns of participation in adult basic education, and the limited number of hours that some programs operate, the amount of time required for adminstration is a critical factor to consider when state and local administrators are determining the feasibility of using performance assessment.

DEVELOPING EXPERTISE

A refrain heard throughout the workshop was the need to have trained and qualified individuals for all phases of performance assessment development, administration, and scoring. A number of presenters observed that the technical expertise of most adult basic education program staff is not sufficient for them to undertake assessment development. Assessment development is a technical field with stringent guidelines, and several presenters suggested that states and programs work collaboratively with psychometricians in the assessment development process. One possible role for adult education staff in the development process might be to provide the applications of content that can be used in the development of assessment tasks.

Another strategy might be to use assessment approaches that minimize the requirement for trained staff to administer and score the assessments, such as computer-based assessment. When both the administration and the scoring can be done electronically, staff do not have to perform these functions. If program staff are to be responsible for assessment administration and scoring, then experts are needed to provide professional development on a periodic basis. All of the activities involved in developing, administering, and scoring performance assessment systems require not only expertise but also time and fiscal resources.