SUMMARY

We are in need of medicine with a heart. . . . The endless physical, emotional, and financial burdens that a family carries when their child dies . . . makes you totally incapable of dealing with incompetence and insensitivity.

Salvador Avila, parent, 2001

The death of a child is a special sorrow, an enduring loss for surviving mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, other family members and close friends. No matter the circumstances, a child’s death is a life-altering experience.

Except when death comes suddenly and without forewarning, physicians, nurses, social workers and other health care personnel usually play a central role in the lives of children who die and of their families. At best, these professionals will exemplify “medicine with a heart,” helping all involved to feel that they did everything they could to help, that preventable suffering was indeed prevented, and that the parents were good parents. At worst, families’ encounters with the health care system will leave them with painful memories of their child’s unnecessary suffering, bitter recollections of careless and wounding words, and lifelong regrets about their own choices. In between these poles of medicine, families will often experience both excellent care and incompetence, compassion mixed with insensitivity, and choices made and then later doubted.

Moving the typical experience of children and families toward the best care and entirely eliminating the worst care is an achievable goal. It is a goal that will depend on shifts in attitudes, policies, and practices involving not only health care professionals but also those who manage, finance, and regulate health care. That is, it will require system changes, not just indi-

vidual changes. Improvement will also require more clinical and health services research to fill gaps in our knowledge of what constitutes the “best” palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care for children and families with differing needs, values, and circumstances.

Viewed broadly, palliative care seeks to prevent or relieve the physical and emotional distress produced by a life-threatening medical condition or its treatment, to help patients with such conditions and their families live as normally as possible, and to provide them with timely and accurate information and support in decisionmaking. Such care and assistance is not limited to people thought to be dying and can be provided concurrently with curative or life-prolonging treatments. End-of-life care focuses on preparing for an anticipated death (e.g., discussing in advance the use of life-support technologies in case of cardiac arrest or other crises or arranging a last family trip) and managing the end stage of a fatal medical condition (e.g., removing a breathing tube or adjusting symptom management to reflect changing physiology as death approaches). Together, palliative and end-of-life care also promote clear, culturally sensitive communication that assists patients and families in understanding the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options, including their potential benefits and burdens.

The death of a child will never be easy to accept, but health care professionals, insurers, educators, policymakers, and others can do more to spare children and families from preventable suffering. Although research is needed to assess systematically the strengths and limitations of different care strategies, promising models exist now in programs being undertaken by children’s hospitals, hospices, educational institutions, and other organizations. Some of these programs focus on better preparing pediatricians and other child health specialists to understand and routinely apply the principles of palliative and end-of-life care in their practice. For example, some pediatric residency review committees have added requirements for training in aspects of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care. Other innovative programs aim to identify and reform specific clinical, organizational, and financing policies and practices that contribute to care that is ineffective, unreliable, fragmented, or financially out of reach. The federal government is sponsoring several demonstration projects to test modifications in current Medicaid policies to improve care coordination and access, and some private health plans are also making coverage of hospice and palliative care for children more flexible.

This report builds on two earlier Institute of Medicine (IOM) reports— Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life (1997) and Improving Palliative Care for Cancer (2001). It continues their arguments that medical and other support for people with fatal or potentially fatal conditions often falls short of what is reasonably, if not simply, attainable. Specifically, this report stresses the following themes:

-

The death of a child has a devastating and enduring impact.

-

Too often, children with fatal or potentially fatal conditions and their families fail to receive competent, compassionate, and consistent care that meets their physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.

-

Better care is possible now, but current methods of organizing and financing palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care complicate the provision and coordination of services to help children and families and sometimes require families to choose between curative or life-prolonging care and palliative services, in particular, hospice care.

-

Inadequate data and scientific knowledge impede efforts to deliver effective care, educate professionals to provide such care, and design supportive public policies.

-

Integrating effective palliative care from the time a child’s life-threatening medical problem is diagnosed will improve care for children who survive as well as children who die—and will help the families of all these children.

The report recognizes that while much can be done now to support children and families, much more needs to be learned. The analysis and recommendations reflect current knowledge and judgments, but new research and insights will undoubtedly suggest modifications and shifts in emphasis in future years.

CONTEXT AND CHALLENGES

In the United States and other developed countries, many infants who once would have died from prematurity, complications of childbirth, and congenital anomalies (birth defects) now survive. Likewise, children who previously would have perished from an array of childhood infections today live healthy and long lives, thanks to sanitation improvements, vaccines, and antibiotics. In the space of a century, the proportion of all deaths in the United States occurring in children under age 5 dropped from 30 percent in 1900 to just 1.4 percent in 1999. Infant mortality dropped from approximately 100 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1915 to 7.1 per 1,000 in 1999. Nonetheless, children still die. Approximately 55,000 children ages 0 to 19 died in 1999.

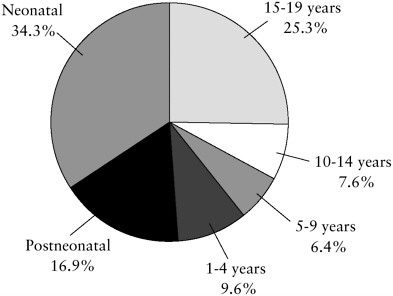

Patterns of child mortality differ considerably from patterns for adults, especially elderly adults who die primarily from chronic conditions such as heart disease and cancer. Palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care must take these differences into account. As shown in Figure S.1, about half of all child deaths occur during infancy. Most of these deaths occur soon after birth from congenital abnormalities or complications associated with pre-

FIGURE S.1 Percentage of total childhood deaths by age group (1999).

maturity, pregnancy, or childbirth. For older infants, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) is an important cause of death.

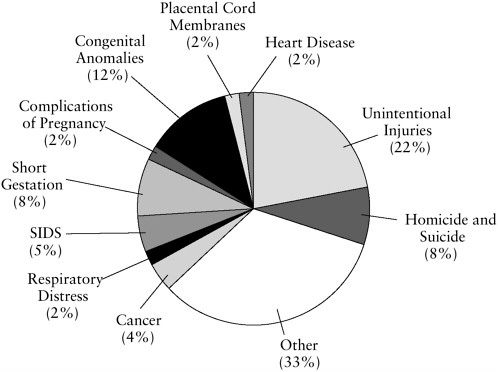

For older children and teenagers, unintentional and intentional injuries are the leading causes of death. Overall, injuries account for approximately 30 percent of child deaths (Figure S.2). Given the importance of sudden and unexpected deaths from injuries and SIDS, efforts to improve care for children and to provide support for bereaved families must extend to emergency first-response personnel, including police, emergency department staff, and staff of medical examiners’ offices. Among fatal chronic conditions, the most important are cancers, diseases of the heart, and lower respiratory conditions.

Common Problems Experienced by Both Children and Adults

Some deficits in palliative and end-of-life care for children parallel those experienced by adults. For example, frightened and upset patients and families may receive confusing or misleading explanations of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options. They may likewise be provided too little opportunity to absorb shocking information, ask questions, and reflect on goals and decisions, even when no immediate crisis drives decisionmaking. Patients at all ages suffer from inadequate assessment and management of pain and other distress, despite the ready availability of therapies known to help most patients. For both children and adults, physicians may advise and

FIGURE S.2 Percentage of total childhood deaths by major causes (1999).

initiate treatments without adequate consideration or explanation of their potential to cause additional suffering while offering no or virtually no potential for benefit. Because clinicians, patients, and families are reluctant to discuss death and dying, opportunities are routinely missed to plan responses for the reasonably predictable crises associated with many fatal medical problems. Failures to prepare for death may deprive families of the chance to cherish their last time with a loved one and say their final good-byes.

Further, if children or adults require complex care from multiple providers of medical and other services, they and their families may find this country’s fragmented health and social services systems to be confusing, unreliable, incomplete, and exhausting to negotiate. Even experienced physicians, social workers, and others are frequently frustrated and stymied by these systems. At the same time, patients, families, and providers may feel that they are in a constant battle with health plans over coverage and payment policies that favor invasive medical and surgical procedures, discourage interdisciplinary care, and undervalue palliative services, including the time needed to fully and effectively inform and counsel patients and

families facing fatal or potentially fatal conditions. Other children and adults suffer because they lack health insurance altogether.

Issues Unique to or Particularly Evident with Children

Notwithstanding these common problems, certain concerns in palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care are unique to or particularly evident with children. As is often emphasized, children are not small adults. Clinicians, parents, and others working with ill or injured children must consider developmental differences among infants, children, and adolescents that may affect diagnosis, prognosis, treatment strategies, communication, and decisionmaking processes.

Many children who die are born with rarely seen medical conditions, which creates substantial uncertainty in diagnosis, prognosis, and medical management. Even for common medical problems, children’s general physiologic resiliency complicates predictions about their future. In situations laden with fear, anxiety, and desperation, this greater uncertainty adds to the burdens on physicians and families as they try to assess the potential benefits and harms of treatment options and make hard decisions. Further, many communities will not have enough cases of various life-threatening medical conditions in children to generate much local experience and clinical expertise in their evaluation and management, including end-of-life care. As a result, seriously ill children and their families must often travel far from home for treatment, which removes them from their usual sources of emotional support and may disrupt parents’ employment and strain family relationships and finances.

While still mentally competent, adults can create advance directives and other binding documents to guide their care if they later suffer significant loss of decisionmaking capacity. In contrast, states, almost without exception, will not recognize a formal advance directive signed by a minor, even a minor living independently. In most situations, parents have legal authority to make decisions about medical treatments for their child.

Many problems facing children with life-threatening medical conditions and their families and many shortcomings in end-of-life care are embedded in broader social, economic, and cultural problems. Unlike virtually all elderly adults, who are covered by Medicare, approximately 15 percent of children lack public or private health insurance. Children with insurance are covered by myriad private and state programs that have widely differing but poorly documented policies and practices for covering palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement services. On the one hand, this diversity of insurance sources could encourage innovation; on the other hand, it makes it extraordinarily difficult to identify and correct deficiencies in any comprehensive way.

In addition, children and young families are disproportionately represented among immigrants and thus are especially vulnerable to misunderstandings related to differences in language, cultural experiences, and values about life, illness, death, and medical or nonmedical therapies. Millions of children, both immigrants and native born, live with their families in unsafe environments that put them at high risk of injury. Such environments can also make it a challenge to get a child to the doctor, pick up a prescription, or persuade a home care provider to come into the neighborhood. These broader problems are not the subject of this report, but their contribution to deficits in care for children and their families should be recognized in strategies to improve pediatric palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care.

WORKING PRINCIPLES

In general, the basic working principles and starting points set forth in the 1997 IOM report apply to children as well as adults. Some details differ, however, and certain additional values apply either uniquely or with special emphasis to children. Of the principles adopted by this committee (Box S.1), the first three are specific to children; the other four restate earlier principles from the 1997 report in terms of children.

|

Box S.1

|

PROVIDING AND ORGANIZING CHILD- AND FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

Palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care for children with life-threatening conditions and their families has many objectives and dimensions that relate to the physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being of each child and family and to their frequent need for practical help with coordinating care, preparing for the future, and maintaining as normal a life as possible. Depending on a child’s medical condition, his or her plan of care may include a mix of preventive measures, curative or life-prolonging interventions, and rehabilitative services in addition to palliative care. The mix can be expected to change over time as a disease progresses, the goals of care are reconsidered and changed, and the benefits and burdens of therapies are re-evaluated based on guidance and counseling from physicians and others.

When first confronted with the news that their child has a fatal or potentially fatal condition, parents will usually be shocked, perhaps uncomprehending. Initially and thereafter, they may be profoundly reluctant to accept that their child will die and will want to feel that they have tried everything possible to save their child. At the same time, they will want to protect their child from pain and other suffering. Thus, they may simultaneously hold multiple, possibly conflicting goals. This puts an exceptional premium on clear and timely information and sensitive counseling about the potential benefits and harms of different courses of care. Such communication requires not only technical and intellectual skills but also empathy, education, experience, teamwork, time, and reflection—as well as supportive administrative and financing systems.

As parents and clinicians determinedly pursue curative and life-prolonging interventions for an infant, child, or adolescent, they may sometimes fail to appreciate fully the suffering that these interventions may inflict. Not all suffering caused by the pursuit of cure or prolonged life can be prevented, but if the potential sources of distress are not adequately considered, opportunities to prevent or relieve distress will certainly be missed. Care plans should always include steps to assess and prevent physical, emotional, and spiritual suffering. As described by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the goal of palliative care is “to add life to the child’s years, not simply years to the child’s life.”

Formal clinical and administrative protocols are one means of defining expectations and responsibilities for the quality of care provided by health care professionals and institutions. Depending on the aspect of care in question, clinical practice guidelines and institutional protocols may include or be supplemented by ethical guidance, model conversations, checklists, documentation standards, and evaluation plans. They should be based

on the best available scientific evidence and expert judgment, including sound guidelines developed by professional societies and other national groups. Careful local review and adaptation may help meet local needs and win support from those who must implement the guidelines and protocols.

Recommendation: Pediatric professionals, children’s hospitals, hospices, home health agencies, professional societies, family advocacy groups, government agencies, and others should work together to develop and implement clinical practice guidelines and institutional protocols and procedures for palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care that meet the needs of children and families for

-

complete, timely, understandable information about diagnosis, prognosis, treatments (including their potential benefits and burdens), and palliative care options;

-

early and continuing discussion of goals and preferences for care that will be honored wherever care is provided;

-

effective and timely prevention, assessment, and treatment of physical and psychological symptoms and other distress, whatever the goals of care and wherever care is provided; and

-

competent, fair, and compassionate clinical management of end-of-life decisions about such interventions as resuscitation and mechanical ventilation.

Parents repeatedly cite the frustrations they have experienced in coordinating the care needed by a very ill child. The twin tasks of reducing the burdens of care coordination and improving the continuity of care present formidable challenges. This is especially true for children with complex, chronic problems that require inpatient, home, and community-based services from many different professionals and organizations that may be separated geographically, institutionally, and even culturally from each other and that may be subject to different insurance rules and procedures.

Interdisciplinary care teams (including hospice or palliative care teams), case managers, disease management programs, and “medical homes” for children with special health care needs all have a role to play in improving care coordination and continuity. In addition, those caring for children with life-threatening medical conditions need to collaborate in establishing procedures that support coordination, continuity, and timely transmission of information within and across sites of care. They also should assign specific responsibility to individuals and groups for implementing all policies and procedures related to palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care.

Recommendation: Children’s hospitals, hospices, home health agencies, and other organizations that care for seriously ill or injured children should collaborate to assign specific responsibilities for implementing clinical and administrative protocols and procedures for palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care. In addition to supporting competent clinical services, protocols should promote the coordination and continuity of care and the timely flow of information among caregivers and within and among care sites including hospitals, family homes, residential care facilities, and injury scenes.

Children with life-threatening medical conditions are often referred to specialized centers for treatment. Some need little follow-up care, but others require considerable attention after they return home. Especially in more rural areas, these children, their families, and the local health care professionals, community hospitals, and other organizations that serve them need additional support. This support may include proven Internet and interactive telemedicine applications as well as telephone consultations and written guidelines and care plans.

Recommendation: Children’s hospitals, hospices with established pediatric programs, and other institutions that care for children with fatal or potentially fatal medical conditions should work with professional societies, state agencies, and other organizations to develop regional information programs and other resources to assist clinicians and families in local and outlying communities and rural areas. These resources should include the following:

-

consultative services to advise a child’s primary physician or local hospice staff on all aspects of care for the child and the family from diagnosis through death and bereavement;

-

clinical, organizational, and other guides and information resources to help families to advocate for appropriate care for their children and themselves; and

-

professional education and other programs to support palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care that is competent, continuous, and coordinated across settings, among providers, and over time (regardless of duration of illness).

Parents (or guardians or other designated adults) will, in most cases, have legal authority to make decisions about a child’s medical care. Nonetheless, excluding children and, particularly, adolescents from conversations about their diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment strategies can isolate these patients emotionally and prevent parents and clinicians from truly

appreciating a child’s values, goals, and experience of his or her disease and its treatment.

Recommendation: Children’s hospitals, hospices, and other institutions that care for seriously ill or injured children should work with physicians, parents, child patients, psychologists, and other relevant experts to create policies and procedures for involving children in discussions and decisions about their medical condition and its treatment. These policies and procedures—and their application—should be sensitive to children’s intellectual and emotional maturity and preferences and to families’ cultural backgrounds and values.

After a child dies, friends, neighbors, spiritual advisers, hospice personnel, grief counselors, and others in the local community may provide most of the bereavement and practical support for a family. Parents or siblings may also seek care from their personal physicians or a psychotherapist. Still, the physicians, nurses, social workers, and others who cared for the child can meaningfully “be with” the family in a variety of ways in the days and months following the child’s death. An abrupt end to contact can feel like—and be—a kind of abandonment.

Recommendation: Children’s hospitals and other hospitals that care for children who die should work with hospices and other relevant community organizations to develop and implement protocols and procedures for

-

identifying and coordinating culturally sensitive bereavement services for parents, siblings, and other survivors, whether the child dies after a prolonged illness or after a sudden event;

-

defining bereavement support roles for hospital-based and out-of-hospital personnel, including emergency medical services providers, law enforcement officers, hospital pathologists, and staff in medical examiners’ offices; and

-

responding to the bereavement needs and stresses of professionals, including emergency services and law enforcement personnel, who assist dying children and their families.

FINANCING

Approximately two-thirds of children are covered by employment-based or other private health insurance. About one-fifth are covered by state Medicaid or other public programs, but some 14 to 15 percent of children under age 19 have no health insurance. In this latter group, some children

will receive care paid for or provided by “safety-net” providers, private philanthropies, and other sources, but some will go without needed services. The diverse sources of payment for children’s health care make it difficult to obtain a comprehensive picture of coverage, reimbursement, and other problem areas, but certain general problems are evident.

For insured children and families, coverage limitations, provider payment methods and rules, and administrative practices can discourage timely and full communication between clinicians and families and may restrict access to effective palliative and end-of-life care. Low levels of payment to providers can make it difficult for health care professionals, hospitals, and hospices to provide certain treatments or even accept some high-cost patients. At the same time, financing policies can promote excessive use of advanced medical technologies and inappropriate transitions between settings of care. In addition, as employers or states restructure their health insurance programs, families are often subject to changes in health plans, provider networks, or terms of coverage (e.g., reduction in home health care benefits). These changes may disrupt continuity of care, including relationships with trusted providers.

Most private health plans, particularly those sponsored by large employers, appear to cover hospice care to some extent, as do nearly all state Medicaid programs. Medicaid programs and some private health plans follow Medicare in limiting hospice care to patients who are certified to have a life expectancy of six months or less and are willing to forgo further curative or life-prolonging care. Such requirements are particularly trouble-some for children whose life expectancy is uncertain or whose parents cannot face relinquishing efforts to save or extend their child’s life.

Recommendation: Public and private insurers should restructure hospice benefits for children to

-

add hospice care to the services required by Congress in Medicaid and other public insurance programs for children and to the services covered for children under private health plans;

-

eliminate eligibility restrictions related to life expectancy, substitute criteria based on a child’s diagnosis and severity of illness, and drop rules requiring children to forgo curative or life-prolonging care (possibly in a case management framework); and

-

include outlier payments for exceptionally costly hospice patients.

In addition to targeting restrictive hospice coverage, this recommendation also is directed at limitations in the current hospice per diem payment method. Research and experience suggest that patients with particularly high-cost needs are often denied hospice or are accepted on the condition

that certain expensive services will not be provided by the hospice. An outlier payment system (similar to that adopted by Medicare for inpatient hospital care) for exceptionally high-cost hospice patients should help to reduce access problems by protecting hospices from some financial losses associated with serving these patients.

Even with these changes, additional reforms are needed to promote the integration of palliative care from the time of diagnosis through death and into bereavement and to make palliative care expertise more widely available. If enrollment in hospice is not possible or appropriate for a child, palliative care consultations and counseling for families should be covered.

Further, to recognize the required role of parents in decisionmaking for children, physician reimbursements should be adequate to cover intensive communication and counseling of parents, whether or not the child is present. In addition, bereavement care should be covered as such, whether or not part of a hospice’s services. Otherwise, insured parents or siblings who seek counseling generally will be covered only under diagnoses such as depression, which could result in later problems in securing health insurance. Although the committee does not believe that adding these services will be expensive because the number of children who die after extended illnesses is relatively small, it recognizes the cost pressures on private health plans and state Medicaid programs. Thus, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should develop estimates of the cost of adopting these recommendations in Medicaid. As the results of several hospice demonstration projects become available, other adjustments in Medicaid policies may be identified.

Recommendation: In addition to modifying hospice benefits, Medicaid and private insurers should modify policies restricting benefits for other palliative services related to a child’s life-threatening medical condition. Such modifications should

-

reimburse the time necessary for fully informing and counseling parents (whether or not the child is present) about their child’s (1) diagnosis and prognosis, (2) options for care, including potential benefits and harms, and (3) plan of care, including end-of-life decisions and care for which the family is responsible;

-

make the expertise of palliative care experts and hospice personnel more widely available by covering palliative care consultations;

-

reimburse bereavement services for parents and surviving siblings of children who die;

-

specify coverage and eligibility criteria for palliative inpatient, home health, and professional services based on diagnosis (and, for

-

certain services, severity of illness) to guide specialized case managers and others involved in administering the benefits; and

-

provide for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop estimates of the potential cost of implementing these modifications for Medicaid.

To implement the recommendations related to improved access to hospice and palliative care, child health professionals, insurers, and researchers will have to work together to define eligibility criteria related to diagnosis and, as appropriate, severity of illness. On a more general level, CMS should take the lead in examining the appropriateness of diagnostic, procedure, and other classification schemes that were originally developed for adult services and are now used by many Medicaid programs and private health plans that cover children. These schemes include diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for hospital payment and the resource-based relative value scale (RVRBS) for physician payment. Also, given the confusion about billing for palliative care services and the frequent denials of payment for improper coding or documentation, children’s access to care may also be improved by providing clearer guidance about accurate coding and documentation of covered palliative services.

Recommendation: Federal and state Medicaid agencies, pediatric organizations, and private insurers should cooperate to (1) define diagnosis and, as appropriate, severity criteria for eligibility for expanded benefits for palliative, hospice, and bereavement services; (2) examine the appropriateness for reimbursing pediatric palliative and end-of-life care of diagnostic, procedure, and other classification systems that were developed for reimbursement of adult services; and (3) develop guidance for practitioners and administrative staff about accurate, consistent coding and documenting of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement services.

LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES

Questions and disagreements about what constitutes appropriate medical treatment for infants and children with severe and often fatal medical problems are frequent topics in the bioethics literature and occasionally in high-profile litigation. One goal of palliative care is to minimize avoidable conflicts that can arise as a result of failures in communication, insufficient attention to goal setting and care planning, and inappropriate clinical care. Continued efforts at the individual and the organizational level can contribute to the prevention and resolution of conflicts about clinical care, for example, by defining procedures for identifying and managing situations

that pose high risks for conflict, developing and testing communication protocols to prevent or defuse conflict, establishing procedures for ethics consultations (or, in some cases, psychological counseling), and developing evidence-based practice guidelines that clarify the benefits and burdens of medical interventions in different clinical situations.

EDUCATION OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Whether the issue is inattention to pain or other symptoms, poor communication, or a clinician’s own anxieties about death, children and families suffer when they encounter pediatricians and other professionals who are ill-prepared to provide competent and compassionate palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care. By itself, education cannot ensure such care or guarantee desired changes in attitudes or behaviors, but it must provide the essential foundation of scientific knowledge, skills, and ethical understanding for all professionals who treat infants, children, and adolescents.

In addition to supporting changes in pediatric generalist and specialist education and consistent with the 1997 IOM report, this committee strongly supports the continued evolution of palliative care as a defined and accepted area of teaching, research, and patient care expertise. The development of a group of specialists in pediatric palliative care has begun, often with support from the larger group of palliative care specialists who care for adults. The numbers of such specialists are still small, but they have a central role not only in providing care but also in enlisting other clinicians, educators, professional societies, research funders, managers, and policymakers to support improvements in pediatric palliative care. Although improved reimbursement will help sustain and expand the ranks of specialists in pediatric palliative care, relevant academic leaders and medical center administrators must also recognize such expertise as essential to meeting their institution’s educational and service missions.

Recommendation: Medical, nursing, and other health professions schools or programs should collaborate with professional societies to improve the care provided to seriously ill and injured children by creating and testing curricula and experiences that

-

prepare all health care professionals who work with children and families to have relevant basic competence in palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care;

-

prepare specialists, subspecialists, and others who routinely care for children with life-threatening conditions to have advanced competence in the technical and psychosocial aspects of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care in their respective fields; and

-

prepare a group of pediatric palliative care specialists to take lead responsibility for acting as clinical role models, educating other professionals, and conducting research that extends the knowledge base for palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care.

Even for medical conditions that are invariably or often fatal, classroom lectures, clinical rotations, and medical textbooks focus almost exclusively on the pathophysiology of disease and the conventional or experimental interventions that might prolong life—often with little regard for the likelihood of success and with little attention to the burdens experienced by dying patients and their families. In one recent survey of pediatric oncologists, respondents reported that the most common way they learned about end-of-life care was “trial and error.” Experience in practice is an important and necessary teacher, but relying on such unstructured and unguided experience puts children and families at risk of much preventable suffering. Even in the crowded undergraduate medical curriculum, opportunities exist to use palliative care and end-of-life issues as powerful illustrations in didactic and clinical teaching.

Recommendation: To provide instruction and experiences appropriate for all health care professionals who care for children, experts in general and specialty fields of pediatric health care and education should collaborate with experts in adult and pediatric palliative care and education to develop and implement

-

model curricula that provide a basic foundation of knowledge about palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care that is appropriate for undergraduate health professions education in areas including but not limited to medicine, nursing, social work, psychology, and pastoral care;

-

residency program requirements that provide more extensive preparation as appropriate for each category of pediatric specialists and subspecialists who care for children with life-threatening medical conditions;

-

pediatric palliative care fellowships and similar training opportunities;

-

introductory and advanced continuing education programs and requirements for both generalist and specialist pediatric professionals; and

-

practical, fundable strategies to evaluate selected techniques or tools for educating health professionals in palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care.

DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH

Among the most common phrases in this report are “research is limited” and “systematic data are not available.” Research to support improvements in palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care constitutes only a tiny fraction of research involving children. Likewise, research involving children and their families occupies a small niche in the world of research on palliative and end-of-life care, which itself is small in comparison to other areas of clinical and health services research. Thus, clinicians and parents must often make decisions about the care of children with little guidance from clinical or health services research.

Recommendation: The National Center for Health Statistics, the National Institutes of Health, and other relevant public and private organizations, including philanthropic organizations, should collaborate to improve the collection of descriptive data—epidemiological, clinical, organizational, and financial—to guide the provision, funding, and evaluation of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care for children and families.

In the 2001 report Improving Palliative Care for Cancer, the IOM’s National Cancer Policy Board included two recommendations aimed at stimulating palliative care research in “centers of excellence” designated by the National Institutes of Health and encouraging such centers to take a lead role as agents of national policy in promoting palliative care. This report endorses a similar strategy to use federally funded pediatric oncology centers, neonatal networks, and similar structures to promote attention to palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care in both pediatric clinical trials and regular patient care. By organizing multiple sites to investigate a common problem using a common methodology, such a strategy should increase the numbers of children involved in studies and increase the credibility of the findings. It should also stimulate the development of investigator expertise in pediatric palliative care research and encourage the formulation and successful completion of more high-quality research projects.

Recommendation: Units of the National Institutes of Health and other organizations that fund pediatric oncology, neonatal, and similar clinical and research centers or networks should define priorities for research in pediatric palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care. Research should focus on infants, children, adolescents, and their families, including siblings, and should cover care from the time of diagnosis

through death and bereavement. Priorities for research include but are not limited to the effectiveness of

-

clinical interventions, including symptom management;

-

methods for improving communication and decisionmaking;

-

innovative arrangements for delivering, coordinating, and evaluating care, including interdisciplinary care teams and quality improvement strategies; and

-

different approaches to bereavement care.

This report also suggests more specific directions for research in a number of areas including symptom control, financing, service organization and delivery, perinatal loss, emergency medical services, and education. Some research in these and other areas will focus narrowly on children who have died or who are expected to die. Other research will include children who have survived or may survive life-threatening medical problems. Both kinds of research should provide knowledge that informs and improves the care of children who survive as well as those who do not. It should likewise help every family that suffers with a seriously ill or injured child. Indeed, all of the recommendations in this report, if implemented, should help create a care system that all children and families can trust to provide capable, compassionate, and reliable care when they are in need.