Page 48

States' Efforts in Small Business Development: Two Models

David N.McNelis

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Depending on the diversity of the existing business base, states have set different goals and approaches to economic development in the high-tech area. Two models are presented herein—one from Nevada, which tends to emphasize the importation of businesses from areas outside the state, and the other from North Carolina, which emphasizes the seeding and nurturing of new high-tech businesses from within the state.

Historically, the various economic development authorities in the State of Nevada have had only minimal success in promoting the immigration of advanced technology companies or the growth of existing or new advanced technology companies from within the state. For example, of the 78 new enterprises for FY2000 for which origin data is available at the Nevada Commission on Economic Development ( www.expand2nevada.com/companies/recent.html ), 67 originated outside the state. Also of note, of the total of 98 new enterprises, 47 are in manufacturing and only 1 is in R&D. The other new businesses are in either the service or the distribution sectors.

Only as recently as 1991 did Nevada seriously undertake to pool the resources of the university system, state government, and private industry. A visionary group of Nevada leaders, in recognition of the need to diversify the state's economy and build on emerging university-based technology, formed Nevada Industry Science Engineering and Technology (NISET) to lead this effort. The organization served to create an environment that was politically and economically attractive to the technology-based businesses and strove to assist the regional development agencies in attracting them to Nevada. In that same time frame, the uni

Page 49

versity system initiated an effort to develop and implement an intellectual property policy and a technology transfer program.

As background, several years ago most technology in Nevada was associated with the federal government, i.e., with the Nevada Test Site or the Department of Defense or with the University of Nevada System. Because of the nature of the business and security concerns, the operation of the Nevada Test Site has essentially been a closed industry and now, with the exception of activities at Yucca Mountain and its use as a geological repository, it is a nongrowth industry with little opportunity for the development of spin-off companies. The main industry in Nevada now is gaming and tourism, and diversification, which was not attractive to the casinos in the past, is now considered essential to the sustainability of the gaming and tourism industry.

Small companies in Nevada are the backbone of the business development community. For example, 40 percent of the new businesses in Clark County, Nevada (the county that includes the city of Las Vegas) have four employees or fewer; nearly 20 percent have 5 to 9 employees and almost 13 percent have from 10 to 19 employees. By contrast, only 0.3 percent of the businesses in Clark County have 1,000 or more employees, and 0.2 percent have from 500 to 999 employees.

More generally, the common characteristics of most state technology development programs beginning in the early 1980s include the creation of tripartite linkages between state economic development agencies, universities, and private industry; a recognition of the importance of technology development as a key ingredient of economic renewal and diversity; and a significant investment of funds. Matching funding, however, is typically required either from federal, state, or private sources.

Differences in these programs tended to be more numerous. Some of the more significant differences were the degree to which basic or applied research is emphasized; the nature of the relationship and degree of private sector involvement; the manner in which state funds are distributed; and the degree of accountability that is applied to the programs.

In 1983 the North Carolina State Legislature established the Technology Development Authority (NCTDA) ( www.nctda.com ) to create jobs and wealth throughout the state and gave it authority to establish incubators to transfer technologies into commercial applications by private industry. Since then the NCTDA has expanded its offerings to effectively provide and connect entrepreneurs through business incubation, venture capital, technology transfer, rural initiatives, and entrepreneurial expertise to commercialize promising business opportunities.

The incubators typically provide office and laboratory space, consultant expertise, an administrative infrastructure, and Internet access. The goal, of course, is to graduate, and the incubators provide incentives by

Page 50

setting terms for tenure and by periodically raising the charges for rent and support.

The documented return on investment for the NCTDA indicates that

-

There are now 27 operational TDA-managed business incubators in North Carolina (and more than 800 nationwide).

-

More than 50 new companies have graduated from the Research Triangle Park TDA area alone.

-

The TDAs have accounted for more than 12,000 new well-paying jobs.

-

During the past year, more than $5.9 million in investments was made in 33 projects.

-

Over the past year, the TDA has approved nearly $600,000 in loans for rural enterprises.

-

A technology development partnership has been formed with the administration of the 16 campuses of the University of North Carolina.

-

There are over 700 enterprises involved in the incubators.

-

Each dollar provided by the TDA (i.e., a public subsidy) has resulted in $46 in matching funds raised from other sources, mainly venture capital. According to the National Business Incubation Association (NBIA), $45 is also generated in local tax revenues for each dollar of public operating subsidy provided the incubator, clients and graduates.

-

A total of $12 million in state, local, and sales taxes has been generated.

-

The internal rate of return during 1996 was 39 percent.

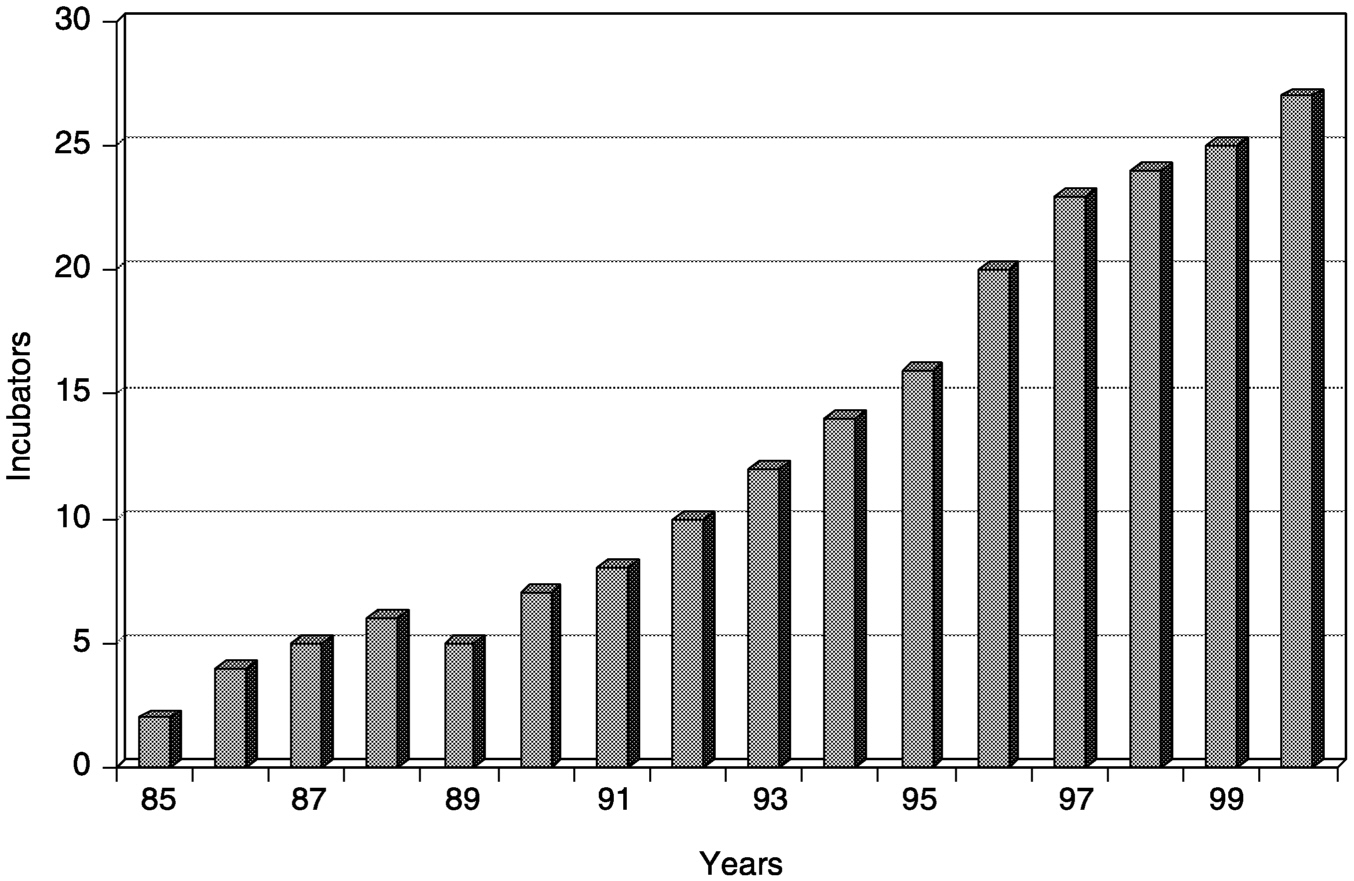

Figure 1 shows the growth of these incubators in the State of North Carolina during the period 1985–2000. What is indicated here is that this highly proactive mode of encouraging and assisting entrepreneurs and small enterprises in North Carolina (and elsewhere in the United States) is a relatively recent activity.

Of the enterprises in the North Carolina incubators, approximately 38 percent are women-owned and about 41 percent are in a manufacturing business. There are now more than 500 graduated enterprises, of which approximately 88 percent stay within a 30-mile radius of the incubator. Those graduated enterprises have averaged over $1 million in sales. The National Business Incubation Association ( www.nbia.org/info/fact_sheet.html ) provides corroborative national statistics, i.e., member incubators report that 87 percent of all firms that graduated from their incubators are still in business and 84 percent of incubator graduates stay in their communities and continue to provide a return to their investors. More importantly, the NBIA reports that the startup firms annually increased sales by $240,000 each and added an average of 3.7 full- and part-

Page 51

FIGURE 1 North Carolina incubators, 1985–2000.

time jobs per firm. Also, for every 50 jobs created by an incubator client, an additional 25 jobs are generated in the community.

One example of a highly innovative enterprise that graduated relatively recently from a North Carolina incubator is Blue 292. Blue 292 ( www.blue292.com/blue292/default_ns.asp ) is a business-to-business Internet exchange for environmental, health, and safety products and services. The Research Triangle Park-based company designs customized secure websites that match customers and the best suppliers of these services. It includes testing and monitoring equipment, sampling supplies, and analytical glassware, as well as staffing, training, analytical laboratory, and compliance services. Blue 292 combines market expertise with worldclass technology to allow major international companies to meet the challenge of compliance in a systematic and practical manner. Their software is designed to be easily integrated into a client company's existing business system and can be tailored to meet their unique needs.

In general, in the United States, universities and nongovernmental organizations have, over the past decade or so, aggressively sought to establish an endowment to support stability and growth. According to one such example from the Entrepreneurial Development Center of North Carolina State University (NCSU), the data indicate that during the 100-year period from 1898–1998, five new enterprises were formed around NCSU technologies. The University holds an equity interest in two of

Page 52

those new enterprises. During the next two years, 15 new companies were formed about NCSU technologies, and the University holds an equity position in eight of those new enterprises. Those 15 companies also caused the creation of 220 new jobs. There is, of course, a difference between the number of companies that launch a new business and the number that survive. As indicated previously, many do survive, however, and a few develop into major enterprises.

A sample highlighting the diversity of other small business development programs in North Carolina includes:

Small Business and Technology Development Center (SBTDC). The SBTDC, organized as an interinstitutional counseling and technical assistance program of the University of North Carolina, has as its mission supporting the growth and development of the state's economy by encouraging entrepreneurship, assisting in the creation and expansion of small businesses, and facilitating technology development and transfer ( www.sbtdc.org ). The SBTDC maintains 15 offices across the state and The SBTDC maintains 15 offices across the state and has, since its inception in 1984, provided managerial and technical assistance to thousands of new and established small business owners.

NC Biotechnology Center. The NC Biotechnology Center was established in 1981 by the State to support biotechnology research, development and commercialization statewide ( www.ncbiotech.org ). The Center assists in biotechnology startup enterprises in business development, science, and education.

MCNC. MCNC is a unique corporation that provides access to advanced electronic and information technologies and services for businesses, state and federal government agencies, and North Carolina's education communities to provide clients with a competitive advantage ( www.mcnc.org ).

The Council for Entrepreneurial Development. The CED serves the Research Triangle community of North Carolina by providing a forum for business managers to meet and exchange concepts of mutual interest. The CED also publishes a comprehensive resource directory of the organizations and agencies that provide assistance to startup enterprises. It also serves as a guide for growing a business and includes coverage of such issues as planning, financing, human resources, growth, and selling the business.

Research Triangle Park (RTP). RTP was established in 1959 by the Research Triangle Foundation, a not-for-profit organization, to stimulate the development of technology enterprises in the region. It is recognized internationally as a center for cutting-edge research and development and is now home to more than 140 enterprises with a total of approximately 42,000 employees. It also serves relocating and expanding companies that want access to technology-transfer opportunities made pos

Page 53

sible thanks to its close proximity and ties to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Duke University, and North Carolina State University.

Based on the 1990 census, records of the Small Business Administration indicate that there are a total of 159,745 small businesses in North Carolina (1997 data). Some 229,600 businesses of all sizes are women-owned (1999 data), and based on 1992 data, 29,221 businesses are Afro-American-owned, 3,827 are Asian-owned, and 2,802 are Hispanic-owned.

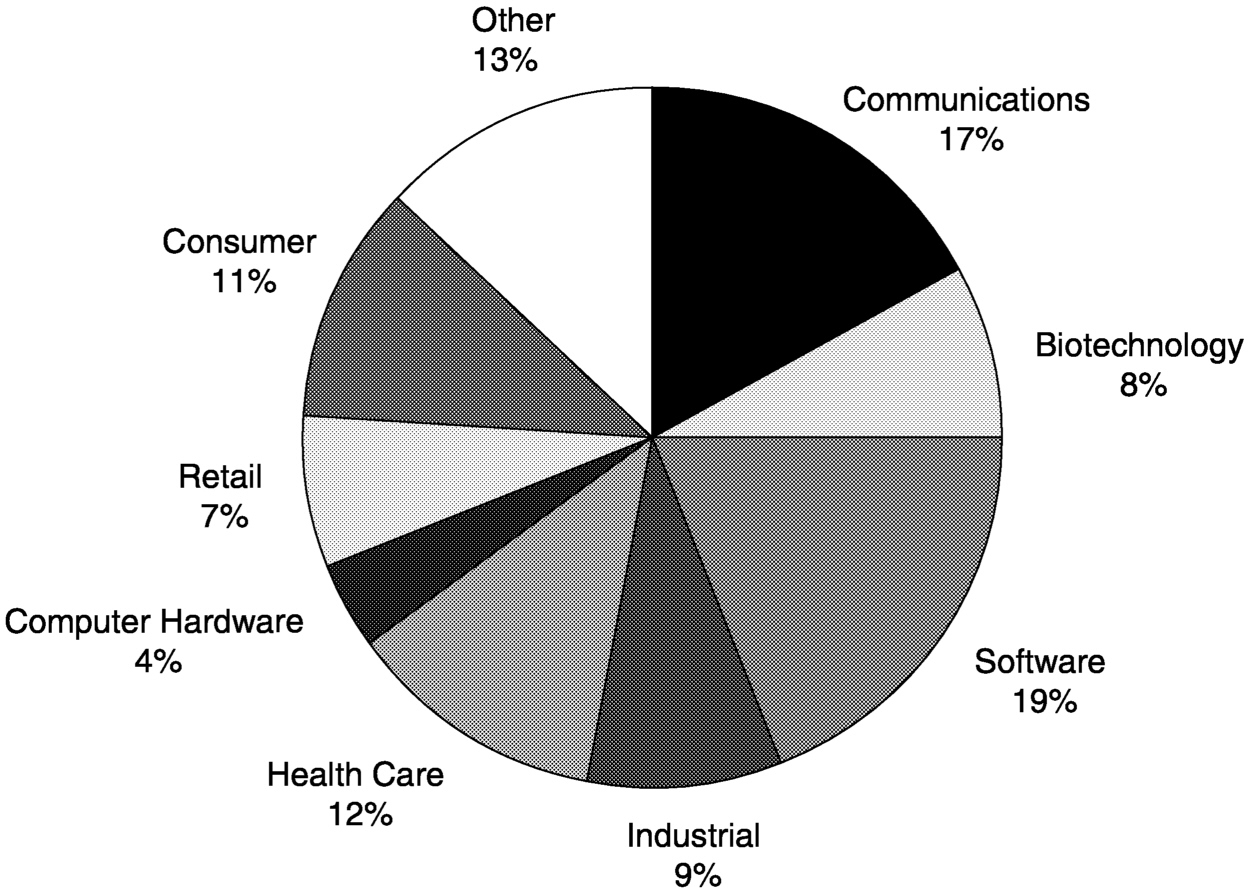

As a clear indication of sector interest, the venture capital investments during 1994–1995 in North Carolina by industry are shown in Figure 2. Almost 70 percent of those investments were in technology-related enterprises (representing 40 percent of the total number of enterprises). During this period, North Carolina had on the order of 17–20 venture capital firms with an estimated capital under management of over $375 million. The preferred size of the investments, however, was between $100,000 and $1 million.

Some of the more common barriers to new business enterprises, regardless of where they start up in the United States, include the following:

-

economies of scale—deter entry by either forcing a major entry and thereby causing the new business to risk a strong reaction from the existing enterprises or forcing a smaller entry and thereby causing a cost disadvantage

FIGURE 2 North Carolina venture capital investments by industry.

Page 54

-

product differentiation—forces new business to spend heavily to overcome existing competition and customer loyalties

-

capital requirements—a large capital outlay is required in order to enter and compete in the market

-

switching costs—expense to buyers to switch from one supplier or supplier's product to another

-

access to distribution channels—the more limited the wholesale or retail channels, the more they are tied up by the competition

-

cost disadvantages independent of scale—the government can limit or even foreclose the entry of a new enterprise with such controls as licensing and limits on access to critical raw materials

-

expected retaliation—history of vigorous retaliation to new entrants from established firms having substantial resources with which to fight back

-

government policy—established firms may have cost advantages not replicable regardless of the new business' size and economies of scale (favorable access to raw materials, favorable locations, government subsidies, learning/experience curve, proprietary product technology)

The Small Business Survival Committee (SBSC) ( www.sbsc.org ) released in July its 2001 ranking of the 50 states plus the District of Columbia according to their respective policy climates for small business and entrepreneurship. The Small Business Survival Index (SBSI), according to its author, SBSC chief economist Raymond J.Keating, “offers a gauge by which to measure and compare how government in the states treat small businesses and entrepreneurships.” It manages to capture much of the governmental burdens impacting critical economic decisions. The SBSI ties together 17 major government-imposed or government-related costs (see Box 1) impacting small businesses and entrepreneurs across a broad spectrum of industries and types of businesses. Many of these are, in fact, taxes.

BOX 1 Government-Imposed or Government-Related CostsPersonal Income Taxes Corporate Income Taxes Sales Taxes Unemployment Taxes Electricity Crime Rates Number of Bureaucrats Internet Taxes State Minimum Wages Capital Gains Taxes Property Taxes Death Taxes Health Insurance Taxes Workers' Compensation Right to Work Status Tax Limitation Status Gas Taxes |

Page 55

These measures are combined into one index number—the small business survival index. According to this index, the most entrepreneur-friendly state for 2001 was Nevada, with a score of 27.060. North Carolina was number 35 (score of 49.590) and the District of Columbia was number 51 (score 65.335).

The conclusion reached by the Small Business Survival Committee is that the best policy environment for entrepreneurship includes low taxes, limited government, restrained regulation, and government protection for life, limb, and property.

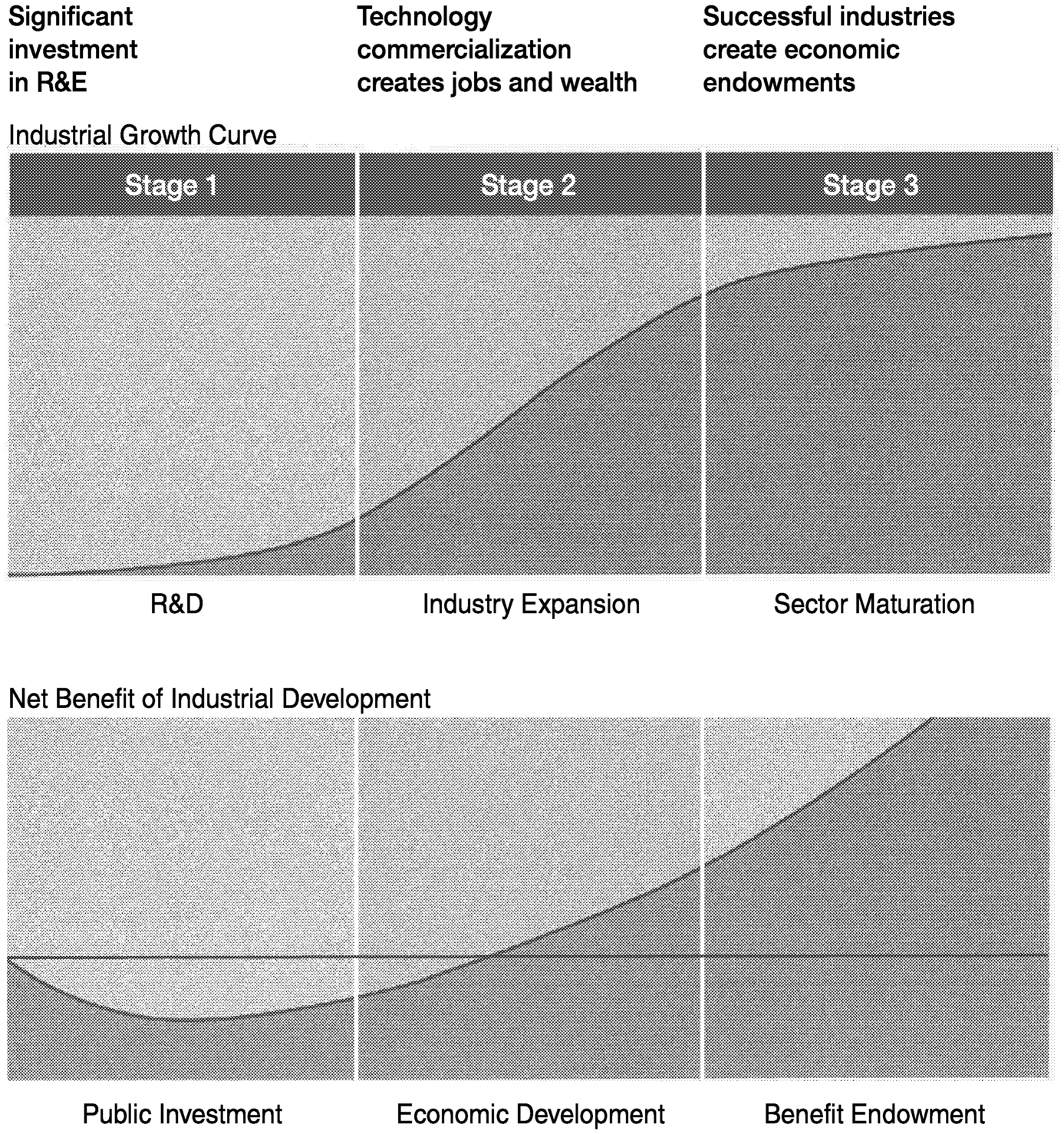

Figure 3 is a graphic from the NCTDA that shows the growth and development of an industry and the net benefits of that industrial devel-

FIGURE 3 Building returns on investment.

Page 56

opment. The first curve shows the magnitude of the industry as it moves through the three stages of R&D, expansion, and finally maturation. The second curve shows, in the first stage, the need for public (private and/or government) investment and actually a negative return on the investment. In the second stage the return becomes positive, and finally, in the third stage—i.e., in the sustainable growth mode—an endowment has been created. For most university and NGO research, reliance for funding (75–85 percent) is on the federal sector. The trend in these institutions was to use any discretionary R&D funds to provide seed funding for research leading to the development of a new proposal. More recently, however, the tendency is for more specific commercialization goals for any IR&D expenditures.

Finally, companies, however, rarely succeed or fail for minor or trivial reasons. The causes are usually substantial and are often self-evident, at least to an outsider. Typical reasons for failure generally include one or more key factors, i.e., that the enterprise was over-borrowed, its management was weak, the enterprise was involved in switching markets, governing or enabling laws changed, a major competitor expanded its business, or the enterprise never reinvested any of its earnings.

REFERENCE

,1996. The Entrepreneur's Guide to Starting and Growing a Business in the Research Triangle.Research Triangle Park, N.C.