6

Society and Culture

Suicide carries a social and moral meaning in all societies. At both the individual and population levels, the suicide rate has long been understood to correlate with cultural, social, political, and economic forces (Giddens, 1964). Suicide is not everywhere linked with pathology but represents a culturally recognized solution to certain situations. As such, understanding suicide and attempting risk prevention requires an understanding of how suicide varies with these forces and how it relates to individual, group and contextual experiences.

Society and culture play an enormous role in dictating how people respond to and view mental health and suicide. Culture influences the way in which we define and experience mental health and mental illness, our ability to access care and the nature of the care we seek, the quality of the interaction between provider and patient in the health care system, and our response to intervention and treatment. This has important implications for treating individuals belonging to different racial, ethnic and cultural groups in the United States, as discussed in detail in the Surgeon General’s Report, Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity (US DHHS, 2001). Cultural variables have a far-ranging impact on suicide. They shape risk and protective factors as well as the availability and types of treatment that might intervene to lessen suicide. This chapter describes a framework for thinking about the continuum of cultural influences on suicide. Next, it explores the roles of the individual, of geographical location, of society, and of historical perspective on the social factors that impact the risk of suicide. Finally, some of the barriers to a full understanding of social and cultural forces on suicide are described.

FRAMEWORK: A SOCIAL SAFETY NET

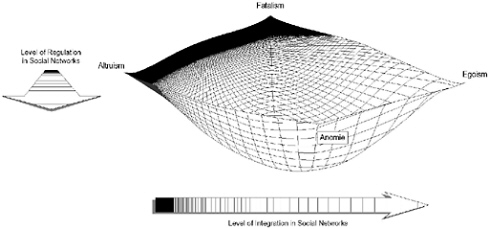

Human connections through informal and formal organizations and the tenor of social change are sources of both distressing and liberating events. They also are the building blocks of a “safety net” that can push individuals toward or pull them away from suicide as a “solution” to their problems. A description of this social safety net originated early in the history of suicide research and evolved over time (Durkheim, 1897/ 1951). As illustrated in Figure 6-1, individuals in crises often find themselves in social and cultural situations where the both the integration (i.e., love, comfort, caring, feelings of belonging) and regulation (i.e., obligations, duties, responsibilities, oversight) are moderate in level. They would be near the bottom of the net where the bonds to others are able to “catch” the individual in crises, protecting them from suicide. However, as a social or cultural group becomes too loosely bound together on either dimension, individuals facing crises are not provided with bonds of either concern or obligation, are not provided with sufficient support to deter the resort to suicide as a solution. These circumstances are presented at the front and left-hand side of the social safety net in Figure 6-1. For example, historically, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the nineteenth century, suicide rates have been reported to be correlated with low levels of social integration (Ausenda et al., 1991). In contemporary times, individuals in the United Kingdom under age 35 who completed suicide

FIGURE 6-1 Networks and the Durkheimian Theory of Suicide. SOURCE: Pescosolido and Levy, 2002. Copyright © 2002. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Science.

were found to be more “rootless” and have withdrawn socially compared to case-controls (Appleby et al., 1999; see also Trout, 1980, on the general role of social isolation on suicide). Bille-Brahe (1987) attributes the differences between Norway and Denmark’s suicide rates to be due to difference in social integration; and in Norway, where the level of integration among young men was reported to be in decline, suicide rates among this groups are increasing. Over time, the doubling of the Irish suicide rate since 1945 appears to be directly related to lower levels of regulation and integration (Swanwick and Clare, 1997).

However, social and cultural groups can also be repressive, stifling, and conducive to suicide. In circumstances where the social group demands 100 percent loyalty and commitment, individuals lose their capacity to decide on options to crises. In these “greedy groups” as Coser and Coser (1979) called them, individuals are called on to demonstrate their commitment to the group and its causes by handing over the power of life and death to the group’s needs (See Box 6-1; see right and back side of the social safety net). Under these circumstances, the social network ties of

|

BOX 6-1 Cases of “Altruistic” or “Fatalistic” Suicide: September 11, 2001, Jonestown, and the Branch Davidians There have been a number of recorded instances of apparently ideologically motivated suicides best explained by understanding the power of the group beliefs over individuals. The terrorists who willingly gave their lives to promote the anti-American cause of the Al-Qaeda terrorist organization; the over 700 individuals in Jonestown, Guyana, who drank cyanide-laced Kool-Aid; and the members of David Koresh’s religious group who allegedly set fire to their compound in the face of the federal government’s attempt to enter, all represent cases where individuals were expected to give up their lives for the group and its cause. In some cases, there is debate whether these are situations where the attachment to the group was so strong that individuals had handed over their lives willingly (over-integration) or whether there was coercion (over-regulation) involved. Nevertheless, there is no evidence, for example, that the religious extremists who become “martyrs” have a mental illness. Palestinian and Israeli psychiatrists and psychologists who have interviewed “suicide bombers” (recruited or foiled) are impressed with their acceptance of suicide as a highly positive status, a moral status that is elevated by their commitment to a radical religious goal. These are all seen as suicides explained not by individual level decisions or problems but by the power of the social and cultural groups to which individuals belonged (Black, 1990; Maris, 1997; Pescosolido, 1994). |

integration and regulation are so dense that the safety net closes up and forms a wall which shatters rather than supports (Pescosolido, 1994). Social and cultural forces that are this strong in their contribution to suicide must be understood fully and considered in risk prevention.

SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN SUICIDE

The social and cultural factors correlated with suicide have been considered at four different levels: individual, geographic, societal, and historical influences. The first, the individual, focuses on the influence of specific events in someone’s life and their affiliation with and participation in social groups. An approach at this level assumes that critical life events or circumstances are responsible for suicides. For example, individuals who face divorce, economic strain, or political repression are often characterized as suicide risks. Here, empirical research often relies on the case-control method, comparing at-risk individuals to others, often matched by age and gender. When considering the second level, the focus is on the geographic distributions of suicide, often within countries, and socio-cultural profiles are assessed to see if they contribute to the suicide rate. These studies rely on suicide rates and characteristics of geographical areas. For example, individuals living in areas of low social integration (e.g., high divorce or unemployment rates) have higher risk of suicide. Third, research at the societal level has examined differences in suicide rates cross-nationally. Different countries, having different institutional arrangements, differ significantly with respect to suicide. For example, Northern European societies, especially Finland and Austria, have especially high rates, as do many Eastern European post-Soviet countries (e.g., Hungary and Russia; see Chapter 2, Table 2-1), whose suicide rates reflect a general worsening of health conditions in a time of societal turmoil and crisis with vast economic, political, and social changes. Further, Confucian societies, Japan and China in particular, have comparatively higher suicide rates than other Asian societies. Moreover, the discrepancy between male and female rate of suicide is much smaller for Asian, especially East Asian, societies. At the historical level of analysis, suicide rates are compared over time periods, to examine either short period effects or longer-term trends. Trends can be examined and correlated with changes over time in social and cultural indictors for various societies. Although these studies use very different approaches and consequently are difficult to compare and analyze (see van Egmond and Diekstra, 1990), they do reflect the importance of understanding context and historical period. The following sections will explore many of the social and cultural factors that influence suicide and will draw upon data from these multiple levels.

Family and Other Social Support

Across societies, family attachments influence suicide probability. Some researchers maintain that the family unit is the single most important factor in understanding suicide (e.g., in India, see Gehlot and Nathawat, 1983). However, others demonstrate that economic circumstance of life must also be considered (e.g., Leenaars and Lester, 1995, see also discussion of the interplay of these variables under occupation and suicide). Whatever the societal context, living alone increases the risk of suicide (Allebeck et al., 1987; Drake et al., 1986; Heikkinen et al., 1995). Family and other social support are protective factors, as will be discussed.

|

My mother also was wonderful. She cooked meal after meal for me during my long bouts of depression, helped me with my laundry, and helped pay my medical bills. She endured my irritability and boringly bleak moods, drove me to the doctor, took me to pharmacies, and took me shopping. Like a gentle mother cat who picks up a straying kitten by the nape of its neck, she kept her marvelously maternal eyes wide-open, and, if I floundered too far away, she brought me back into a geographic and emotional range of security, food, and protection. Her formidable strength slowly eked its way into my depleted marrowbone. It, coupled with medicine for my brain and superb psychotherapy for my mind, pulled me through day after impossibly hard day (Jamison, An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness, 1995:118–119). |

Marital Status

Marital status provides an opportunity to see the convergence of sociodemographic effects on suicide; its influence on suicide rates varies by gender, culture and across the life course. In general, however, across many cultures, marriage is associated with lower overall suicide rates, while divorce and marital separation are associated with increased suicide risk (Allebeck et al., 1987; Charlton, 1995; Heikkinen et al., 1995; Leenaars and Lester, 1999; Lester and Moksony, 1989; Motohashi, 1991; Petronis et al., 1990; Zacharakis et al., 1998). Widowed persons are also more likely to complete suicide (e.g., Heikkinen et al., 1995; Kaprio et al., 1987; Li, 1995; Ross et al., 1990; Zacharakis et al., 1998; Zonda, 1999). Other studies suggest that being single also influences the likelihood of committing suicide (e.g., Charlton, 1995; Heikkinen et al., 1995; Li, 1995; Qin et al.,

2000). Results for suicide attempts and marital status are slightly different. As seen with completions, divorced and single individuals were over-represented among suicide attempters (Schmidtke et al., 1996). However, a study in the Netherlands found the lowest overall rates of attempts were among the widowed (Arensman et al., 1995), perhaps reflecting the lethality of attempts among this cohort (see Chapter 2).

Cultural context provides insight into the role of marital status in suicide. In the United States, Stack (1996) found that among African-Americans, divorce or death of a spouse significantly raised the risk of suicide, but being single did not. The strength of the association between marital status and suicide was less than the effect for whites, which the author suggests is due to stronger family ties.

The impact of marital status also differs for men and women, and varies across the life course. Models that account for gender often have found that divorce increases suicide risk in men only; in women divorce does not seem to exert a strong influence on suicide (e.g., Kposowa, 2000; Pescosolido and Wright, 1990). In Israel, increased divorce rates between 1960 and 1989 were associated with higher suicide rates for men and lower suicide rates for women (Lester, 1997). In contemporary Pakistan, suicides were more prevalent in married than unmarried women (Khan and Reza, 2000). One controlled study (Heikkinen et al., 1995) found that suicides were especially common among never-married men ages 30-39 compared to the general population. Theoretical interpretations of this data frequently echo the suppositions of Durkheim, who proposed that marriage is protective when it is not over- or under-regulating, and provides social integration and support through a strong family network (Durkheim, 1897/1951). For example, reflecting Durkheim’s notion that very early marriage for men is “over-regulating,” high proportions of never-married populations are related to lower suicide rates among young men (Pescosolido and Wright, 1990).

Although the research in this area is incomplete, these results caution against generalizing on the basis of any single sociodemographic factor. Heikkinen and colleagues (1995) suggest that some of the age-related variations in social factors for suicide may be better explained by mental illness and alcohol abuse. An analysis by Qin and colleagues (2000) supported this theory. Controlling for psychiatric hospitalization, they found that marital status was no longer an independent significant suicide risk factor for women. Other research suggests that the quality of the marital bond may be most important; domestic violence seems to increase risk for suicide ideation and attempts across the world (McCauley et al., 1995; Muelleman et al., 1998; Roberts et al., 1997; WHO, 2001). It has also been suggested that when marital ties represent the only or primary source of

social integration and support, the dissolution of the marriage will have an especially strong effect on increasing suicide risk (Pescosolido and Wright, 1990). Integration of individual-level variables is necessary to understand the confluence of these factors.

Parenthood

Being a parent, particularly for mothers, appears to decrease the risk of suicide. In a prospective study of over 900,000 women followed for 15 years, Hoyer and Lund (1993) noted that both having children and the number of children decreased the risk of suicide. Across countries, having a young child appears to be a significant protective factor for women (de Castro and Martins, 1987; Qin et al., 2000). Pregnant women have a lower risk of suicide than women of childbearing age who are not pregnant (Marzuk et al., 1997).

Family Discord and Connectedness

Discord within the family also has an impact on suicide. Increases in the suicide rates in Ireland between 1970 and 1985 were correlated with a general decline in social cohesion as marked by a fall in the marriage rate and rise in the number of separated couples (Kelleher and Daly, 1990). A study in Scotland (Cavanagh et al., 1999) demonstrated that among patients with mental disorders, family conflict increased the risk of suicide by about a factor of 9. The effect of domestic discord also can influence the suicide rate for children and adolescents. Adolescents who had lived in single parent families or who were exposed to parent–child discord were more likely than matched controls to complete suicide (Brent et al., 1994; see also the case of young Canadians, Trovato, 1992). Furthermore, Tedeschi (1999) found that exposure to trauma, such as violence, predicts poor outcomes in children, especially if parental responses are inadequate (Bat-Aion and Levy-Shiff, 1993; Garbarino and Kostelny, 1993) (see also Chapter 5). But if parental physical and mental health are sound, children can do surprisingly well even in the face of terrorism (Freud and Burlingham, 1943; Miller, 1996).

On the other hand, some researchers (Borowsky et al., 2001; Resnick et al., 1997) have noted that perceived parental and family connectedness significantly protected against suicidality for youth. Other studies also demonstrated a protective effect of family connectedness and cohesion on suicidal behavior among American Indian and Alaska Native youth (Borowsky et al., 1999), Mexican American teenagers (Guiao and Esparza, 1995), and a largely white sample of adolescents (Rubenstein et al., 1989).

Social Support

Those who enjoy close relationships with others cope better with various stresses, including bereavement, rape, job loss, and physical illness (Abbey and Andrews, 1985; Perlman and Rook, 1987), and enjoy better psychological and physical health (IOM, 2001; Sarason et al., 1990). Studies have documented that social support can attentuate severity of depression and can speed remission of depression in at-risk groups such as immigrants and the physically ill (Barefoot et al., 2000; Brummett et al., 1998; Shen and Takeuchi, 2001). Studies of youth at risk for adverse outcomes, including suicide, have demonstrated that social support potently buffers the effects of negative life events (Carbonell et al., 1998; O’Grady and Metz, 1987; Vance et al., 1998).

As mentioned above, completed suicide occurs more often in those who are socially isolated and lack supportive family and friendships (e.g., Allebeck et al., 1988; Appleby et al., 1999; Drake et al., 1986). Studies from across sundry countries and ethnic groups show that suicide attempts and ideation among youths and adults correlate with low social support (De Wilde et al., 1994; Eskin, 1995; Hovey, 1999; Hovey, 2000a; Hovey, 2000b; Ponizovsky and Ritsner, 1999), with one study suggesting that perceived social support may account for about half the variance in suicide potential for youth (D’Attilio et al., 1992). Research has demonstrated that social support moderates suicidal ideation and risk of suicide attempts among various racial/ethnic groups, abused youths and adults, those with psychiatric diagnoses, and those facing acculturation stress (Borowsky et al., 1999; Hovey, 1999; Kaslow et al., 1998; Kotler et al., 2001; Nisbet, 1996; Rubenstein et al., 1989; Thompson et al., 2000; Yang and Clum, 1994).

Evidence suggests different mechanisms of support’s influence. Social support sometimes represents part of a protective process that increases self-efficacy and thereby reduces suicidal behavior (Thompson et al., 2000). At other times social support more directly reduces suicidality via reducing psychic distress (Schutt et al., 1994). Furthermore, family and friendship support appear to play somewhat different roles in protecting against suicidality (Rubenstein et al., 1989; Veiel et al., 1988); men and woment may differ in use and types of social support (Heikkinen et al., 1994; Mazza and Reynolds, 1998).

Effective treatment for suicidality, whether medical or psychosocial, involves human contact and support (see Chapter 7). Recent suicide prevention programming to increase social support and other positive variables (e.g., Thompson et al., 2000) builds on emerging evidence suggesting a greater ameliorative effect of increasing protective factors than reducing risk (Borowsky et al., 1999; Vance et al., 1998).

Religion and Religiosity

In general, participation in religious activities is a protective factor for suicide. In the United States, areas with higher percentages of individuals without religious affiliation report correspondingly higher suicide rates (Pescosolido and Georgianna, 1989). Annual variation in the suicide rate tends to correlate with annual variation in church attendance (Martin, 1984). Furthermore, older adults (50 or more years of age) who are involved with organized religion are less likely to complete suicide (Nisbet et al., 2000). Similarly, areas in the former Soviet Union with a strong tradition of religion had lower suicide rates from 1965 to 1984 (e.g., the Caucasus and Central Asia; Varnik and Wasserman, 1992).

The protection afforded by religion may have several components. Involvement with religion may provide a social support system through active social networks (see Stack, 1992; Stack and Wasserman, 1992). Suicide may be reduced with religious affiliation because of the proscription against the act (e.g., Ellis and Smith, 1991). Belief structures and spiritualism may also be protective at an individual level as a coping resource (e.g., Conway, 1985-1986; Koenig et al., 1992) and via creating a sense of purpose and hope (see Chapter 3 on these protective factors) (e.g., Herth, 1989; Werner, 1992; 1996).

Religious Affiliation

Historically, studies of Western Europe indicated that those countries or regions within countries that were Catholic as opposed to those that were Protestant had lower suicide rates; this has been proposed to be related to increased social contact and affiliation in practiced Catholicism (Durkheim, 1897/1951; Masaryk, 1970). In the United States, this classic hypothesis also has received empirical support (Breault, 1986; Lester, 2000b). However, unlike much of Europe, the United States has experienced intensive and widespread denominationalism among Protestant groups. While religion continues to be correlated differentially with suicide, it appears that areas with both a greater presence of Catholics and evangelical or conservative types of Protestantism (e.g., Southern Baptist) report lower suicide rates compared to those with higher representation of mainline or institutional Protestantism (e.g., Episcopalian, Unitarian). The presence of Jewish adherents results in a small but inconsistent effect on reducing suicide rates (Pescosolido and Georgianna, 1989). However, the proportion of Islamic adherents does not appear to be related to suicide rates (Lester, 2000a).

This research points to the social ties formed (by volition and obligation) across these different religious groups rather than differences in

dogma. This conclusion is further supported by evidence that indicates that in the “historical hubs” of religions (e.g., Lutherans in the Midwest, Jews in the Northeast), the protective effects of religious affiliation are stronger. Conversely, where religious adherents are located outside of these places, the effect of affiliation on suicide (e.g., Jews and Catholics in the South) may produce more suicides. It has been suggested that it is precisely in those places where religions have constructed institutions of assistance and informal communities of support that religion’s protective effects are strongest (Pescosolido, 1990).

Studies at the individual level of assessment further explicate the role of religion in reducing risk of suicide. Maris (1981) compared suicide rates among Catholics and Protestants in Chicago between 1966 and 1968. He found that for all age groups and across both sexes, the suicide rate for Protestants was greater than the suicide rate for Catholics. Immigrants to the United States who identified as Catholic report significantly lower lifetime rates of suicide ideation (3.7% vs. 11.8%) and suicide attempts (1.6% vs. 2.6%) than non-Catholic immigrants. Scores on church attendance, perception of religiosity, and influence of religion were negatively associated with suicidal ideation. When sex, marital status, and socioeconomic status were factored in, the perceived influence of the religion item was the strongest significant independent predictor of suicidal ideation. Those individuals who perceived religion to be influential in their lives reported less suicidal ideation, and those individuals who attended church more often reported less suicidal ideation. These findings yielded no support for the notion that affiliation with Catholicsm shows less suicide risk than with other religions, as church attendance rather than religious affiliation accounted for most of the variation in suicide attitudes. These findings do, however, lend support to the notion that religiosity plays a protective role against suicide. Although most studies of religion and suicide have focused on adult samples, some have found that church attendance among youths of various ethnic/racial backgrounds reduces suicide risk, including suicide attempts (Conrad, 1991; Kirmayer et al., 1998; 1996). A large meta-analysis of U.S. adolescent data that controlled for sociodemographic variables indicates that religiousness decreases risk of suicide ideation and attempts in youths (Donahue, 1995).

Religious Beliefs

Actively religious North Americans are much less likely than nonreligious people to abuse drugs and alcohol (associated with suicide), to divorce (associated with suicide), and to complete suicide (Batson et al., 1993; Colasanto and Shriver, 1989). Stack and Lester (1991) found that those individuals who attended church more often reported less approval

of suicide as a solution to life’s problems. In a study involving 100 college students, Ellis and Smith (1991), using the Reasons for Living Inventory (Linehan et al., 1983) and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Paloutzian and Ellison, 1982), found results that strongly indicate a high positive relationship between an individual’s religious well-being (faith in God) and that person’s moral objections to suicide; existential well-being correlated with adaptive survival and coping beliefs (see Chapter 3). Decades-long study of at-risk individuals has also suggested that religious involvement and beliefs can influence positive outcomes by providing persons with a sense of meaning and purpose (Werner, 1992; 1996).

Several epidemiologic studies have reported lower rates of depression among religious persons, whether healthy or medically ill (Kendler et al., 1997; Kennedy et al., 1996; Koenig et al., 1992; Koenig et al., 1997; Pressman et al., 1990). Koenig et al. (1998) also found that intrinsic religiousness (i.e., religious beliefs representing a person’s primary, unifying life motive) significantly increased the speed of remission from depression by 70 percent for every 10-point increase on the Hoge Intrinsic Religiousness scale. These changes were independent of other factors predicted to speed remission, including changing physical health status, religious activity, and social support.

Religious activity has also been found to be protective against suicide risk factors such as alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and anxiety disorder (Braam et al., 1997a; Braam et al., 1997b; Gorsuch, 1995; Koenig et al., 1992; Koenig et al., 1993; Koenig et al., 1994; Pressman et al., 1990). Further, a number of studies provide some evidence that spiritual protective factors (e.g., religious beliefs) may inoculate individuals against stressful life experiences (Conway, 1985-1986; Koenig et al., 1999; McRae, 1984; Pargament, 1990; Pargament et al., 1998; Park and Cohen, 1993; Park et al., 1990). At least one study has found attenuation of immune-inflammatory responses in those who regularly attend religious activities that could not be explained by differences in depression, negative life events, or other covariates (Koenig et al., 1997).

Koenig et al. (1998) noted that using spiritual/religious practices to treat depression and anxiety has been found effective. Propst et al. (1992) found religious therapy resulted in significantly faster recovery from depression when compared with standard secular cognitive-behavioral therapy. Similarly, Azhar et al. (1994) randomized 62 Muslim patients with generalized anxiety disorder to either traditional treatment (supportive therapy and anxiolytic drugs) or traditional treatment plus religious psychotherapy. Religious psychotherapy involved the use of prayer and reading verses of the Holy Koran specific to the person’s situation. Patients receiving religious psychotherapy showed significantly more rapid improvement in anxiety symptoms than those receiving traditional

therapy. Such studies suggest that being exposed to spiritual protective factors may also provide some protection from some types of mental illness associated with suicide.

Cultural Values and Suicide

In some cultures, suicide is morally acceptable under particular circumstances. Although most Western religions forbid suicide (see Chapter 1), some Eastern religions are more accepting. Among Buddhist monks for example, self-sacrifice for religious reasons can be viewed as an honorable act. During the Vietnam War, Buddhist monks set themselves on fire in protest (Kitagawa, 1989). In Japan, attitudes toward suicide are mixed, but some sanction and even glorify suicide when done for “good” reasons for controlling one’s own destiny (Tierney, 1989). The Hindu code of conduct condones suicide for incurable diseases or great misfortune (Weiss, 1994).

Other cultural traditions sanction suicide. For example, in India it is acceptable for a widow to burn herself on her husband’s funeral pyre in order to remain connected to her husband rather than to become an out-cast in society. The traditional belief is that with this act, a husband and wife will be blessed in paradise and in their subsequent rebirth (Tousignant et al., 1998). In Japan, hara-kiri was a traditional suicide completed by warriors in the feudal era (Andriolo, 1998) and as recently at 1945 army officers completed suicide after the defeat of Japan (Takahashi, 1997). Suicide by hara-kiri, a disembowelment, is slow and painful and considered by some to symbolize exercising power over death (Takahashi, 1997).

Some cultures see suicide as an acceptable option in particular situations. Suicide in Japan may be a culturally acceptable response to disgrace. Furthermore, it is more acceptable to kill one’s children along with oneself than to complete suicide alone, leaving the children in others’ care (Iga, 1996; Sakuta, 1995). Similarly, in the Pacific region, suicide represents one culturally recognized response to domestic violence (Counts, 1987). Wolf (1975) reports that Chinese women with no children can demonstrate their faithfulness to their husbands through suicide upon their spouse’s death.

Clearly, a society’s perception of suicide and its cultural traditions can influence the suicide rate. Greater societal stigma against suicide is thought to be protective from suicide, while lesser stigma may increase suicide. Chapter 9 discusses further the ways in which stigma and perceptions of suicide may affect suicide and mental health care in general.

Economic Influences and Socioeconomic Status

Epidemiological analyses reveal that occupation, employment status, and socioeconomic status (SES) affect the risk of suicide. A recent IOM report (2001) describes at length the influence of social factors (including employment and SES) on health in general. Many of the same issues exist when focusing on suicide. Some studies that address these issues for suicide and suicidal behavior are described here.

Occupation

Some professions have higher risk for suicide than others. Physicians and dentists, for example, have elevated suicide rates even after controlling for confounding demographic variables, whereas higher suicide rates for occupational groups such as police officers and manual laborers, may be best explained by the demographics of these subgroups (see Chapter 2). It is interesting that in some northern European countries, rates among physicians show gender differences; women having greater risk than men (in Sweden, see Arnetz et al., 1987; in England and Wales see Charlton, 1995; Hawton et al., 2001; in Finland, see Lindeman et al., 1997; Stefansson and Wicks, 1991). Some suggest that greater access to means among these professions contribute to the higher rates (Pitts et al., 1979). While some find that blue-collar workers are more likely to complete suicide, others find high suicide among professional classes (Kung et al., 1998), confirming earlier theories (e.g., Powell, 1958) suggesting that the risk of suicide is elevated at both ends of the occupational prestige spectrum. Chapter 2 describes recent research on this phenomenon.

Specific influences of occupation-related factors on suicide remain unclear. Mental illness and employment variables influence each other, with mental illness sometimes disrupting employment, and unemployment sometimes exacerbating mental illness. Research has implicated economic strain in marital disruption (e.g., Conger et al., 1990; Kinnunen and Pulkkinen, 1998; Vinokur et al., 1996; White and Rogers, 2000), and Zimmerman (1987) found, for example, that state welfare spending appears to influence suicide rates via increasing income and lowering divorce (see above section on marital status and suicide). The occupation-suicide relationship also demonstrates variability according to ethnic differences. One recent study (Wasserman and Stack, 1999) suggests no difference between Black and White suicide in high-status occupations when controlling demographic factors, whereas Whites evidence greater suicide rates for low-status jobs. South (1984), however, found a positive correlation between diminishing Black-White income gaps and Black sui-

cide rates. Increased income has been shown to increase the risk for attempted suicide in African-American females (Nisbet, 1996). One hypothesis for such relationships (Kirk and Zucker, 1979) posits that as discrimination against Blacks decreases, they are less able to blame external factors/society for life difficulties, and so turn blame inward. Nisbet (1996) contends, however, that observations of income’s effects on Black suicide rates most strongly reflect changes in African Americans’ social support networks as their socioeconomic status changes.

|

HEADLINE: Four Ukrainians kill themselves in separate incidents DATELINE: Kiev Four Ukrainians ended their lives in Kiev in separate overnight incidents, the Interfax news agency reported Thursday. The usual suicide rate in the Ukrainian capital is three or four a month, a city spokesman said. One woman, 76, threw herself from the sixth floor balcony of a hospital where she was undergoing treatment. A man, 74, jumped from his window in an apartment high-rise. Another retiree ended his life by pouring petrol over his body and setting himself on fire in his own apartment. Firemen responding to the scene were able to douse the blaze, but could not save him. Though Ukraines economy is slowly improving, retirees are often forced to live on pensions as small as 20 dollars a month, sometimes not paid on time. A man, 37, hanged himself in his house because of reported business problems. More than 14,000 Ukrainians commit suicide every year, in a population of around 50 million, the report said. SOURCE: Deutsche Presse-Agentur, November 23, 2000. Reprinted by permission of Deutsche Presse-Agentur. |

Such transactional processes between individual characteristics and environmental contexts underscore the complexity of the issue and the lack of transactional, longitudinal research uncovering the relative contributions to suicide risk of occupational stress, professional milieu, discrimination and acculturation, demographics, and means availability.

Unemployment

Unemployment is clearly associated with increased rates of suicide. In a broad review (Platt, 1984), an analysis of individual and aggregate cross-sectional studies and individual and aggregate longitudinal studies showed that almost all demonstrated a greater rate of suicide and/or suicide attempts with unemployment. This relationship has been documented in many countries, including Canada, Australia, Germany, Italy, Trinidad and Tobago, England and Wales, and Taiwan (Cantor et al., 1995; Chuang and Huang, 1996; Hutchinson and Simeon, 1997; Preti and Miotto, 1999; Saunderson and Langford, 1996; respectively: Trovato, 1992; Weyerer and Wiedenmann, 1995). A recent study in the United States, based on National Longitudinal Mortality Study (Kposowa, 2001), revealed a 2-fold increase in risk of suicide among the unemployed. Some gender differences may exist, as noted by Crombie (1990) in an assessment of suicide across 16 countries (e.g., in: Japan, Goto et al., 1994; the U.S., Kposowa, 2001; England and Wales, Lewis and Sloggett, 1998; Italy, Platt et al., 1992; New Zealand, Rose et al., 1999; Northern Ireland, Snyder, 1992). Within Italian counties, for instance, the influence of unemployment on suicide rates was reported to be greater for men than women (Preti and Miotto, 1999). In the United States, a recent analysis (Kposowa, 2001) suggested that while the relationship is stronger in men within the short-term, when followed for 9 years, unemployed women were actually more vulnerable to suicide than unemployed men.

Increases in national unemployment rates have had a mixed influence on suicide rates. Increased unemployment in Ireland has been credited with increased suicide between 1978 and 1985 (Kelleher and Daly, 1990). On the other hand, unemployment rates did not predict suicide rates in Hong Kong from 1976 to 1992, or in either the United States or Canada from 1950 to 1980 (Leenaars et al., 1993; Lester, 1999). In Japan from 1953 to 1972, the suicide rate for both men and women was positively correlated with unemployment. However, after 1972 and through 1986, the relationship did not hold. This change was hypothesized to reflect larger changes in the global economy as a transition from an industrial to a service economy occurred in Japan as it did in many capitalist societies (Motohashi, 1991).

Socioeconomic Status

A strong predictor of suicide, across levels, time, and countries, is socioeconomic disadvantage. Overall suicide rates appear to be associated with indicators of economic distress (Stack, 2000). For example, suicide rates are highest in low-income areas within Stockholm and across

Sweden as a whole (Ferrada-Noli, 1997; Ferrada-Noli and Asberg, 1997). The same relationship holds true in Canada (Hasselback et al., 1991), Australia (Cantor et al., 1995), and London (Kennedy et al., 1999). In addition, perceptions of individuals’ possibilities for earnings (i.e., permanent income) have been implicated in suicide risk (Hamermesh and Soss, 1974). Using individual level data on suicides of men in New Orleans, Breed (1963) documented a link between suicide and indicators of downward mobility, reduced income, and unemployment. In England and Wales, areas characterized by lower social class had higher rates of suicide (Kreitman et al., 1991). Even among those younger than 25, lower social status increased the likelihood of suicide compared to the local population (Hawton et al., 1999).

Similarly, societal-wide economic downturns have been linked to higher suicide rates. For instance in the United States, Wasserman (1984), using a multivariate time-series analysis, found that the average monthly duration of unemployment (1947 to 1977) and the Ayres business index (1910 to 1939) were related to the suicide rate. Pierce (1967) notes that the greatest changes in the economic cycle have been associated with greater increase in the suicide rate.1 Reflecting the importance of social stratification, as discussed earlier, the greatest increases in the British suicide rate occurred in areas with the greatest absolute increase in social fragmentation and economic deprivation (Whitley et al., 1999). In Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong following the decline of Asian post-World War II prosperity (La Vecchia et al., 2000; Schmidtke et al., 1999), suicide rates increased. In contrast, in the Nis region of Yugoslavia, the suicide rates dropped between 1987, when the country was economically and politically stable, and 1999, at the peak of the economic and political crisis (14.8/100,000 to 13.8 in males and 6.8 to 3.7 in females). Likewise, the rate in China remained high in its period of greatest economic growth (Chan et al., 2001). Phillips, Liu, and Zhang (1999) suggest that current high rates of suicide in China are related to social changes resulting from economic reforms that were instituted in 1978. These trends in suicide, repeated in many developing societies, suggest the destabilizing effects of current phases of social change spurred by economic shifts and further points to the critical role of the social environment and larger contextual forces.

Economic conditions can affect suicide in other ways as well. Alcohol consumption and marital discord can increase with financial difficulties, which can increase risk of suicide. Relocation of individuals or families can result as a consequence of unemployment or financial strain. The increased stress of breaking social bonds increase suicide risk (Stack, 2000).

Those left behind may also be at increased risk. For example, in China, 100,000,000 economic migrants from rural to urban areas left behind young wives responsible for small children, care of the elderly, and farming. With limited economic support, many of these women complete suicide as a result of the tremendous pressure (Shiang et al., 1998).

The Political System

During time of war, suicide among the population is generally reduced (Lester, 1993; Somasundaram and Rajadurai, 1995). However, political coercion or violence can increase suicide. In the former Soviet Union, areas experiencing sociopolitical oppression (the Baltic states) and forced social change (Russia) had higher suicide rates compared to other regions (Varnik and Wasserman, 1992). While Sri Lanka’s Tamils have long experienced a high suicide rate, its majority Sinhalese population experienced a low rate until the start of Civil War two decades ago, when its rate increased greatly (Marecek, 1998; Ratnayeke, 1998; Somasundaram and Rajadurai, 1995). Furthermore, war can promote altruistic suicides. In ancient times in China, for example, those soldiers thought to be particularly brave stepped forward in front of battle lines to complete suicide as a demonstration of the fierceness of their loyalty and determination against invading armies from Central Asia (Lin, 1990; Liu and Li, 1990).

General political activity such as United States presidential elections correlates with decreased suicide rates; researchers suggest that this is a consequence of stronger social integration during these times (Boor, 1981). However (Phillips and Feldman, 1973), this correlation is not supported by all studies (Wasserman, 1983).

The relationship between political, social and economic power and suicide rates is interesting, but direct data is limited. A positive correlation has been observed across 26 nations between male and female suicide rates and women’s access to social, economic, and political power (Mayer, 2000). De Castro et al. (1988) showed that in Portugal, the rise of the female independence movement correlated with a significant rise in the female suicide rate, particularly among professional women living in urban areas. This change in the rate may have been mediated through an increase in alcohol use among the professional women subsequent to achieving greater independence. As mentioned in Chapter 2, infrequently-held professional roles (e.g., women entering male-dominated professions) appear to increase suicide risk, though precise pathways of influence remain unknown.

The discussions above regarding occupation/employment and socioeconomic status, and the discussion in Chapter 2 of racial and ethnic differences in suicidality allude to differential social power as reflected by

racial/ethnic and sexual discrimination. The relationship of power to suicide in these contexts is extremely complex; the power a certain group has on a macro-social level must be disentangled from individuals’ perceived personal and interpersonal control, economic power, and self-perception of the ability to foster change. Emerging areas of community and cultural psychology refer to this latter concept as “sociopolitical control,” and have found evidence that sociopolitical control may moderate the relationship between certain risk factors and mental health outcomes (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 1999) by contributing to self-esteem and promoting self-efficacy. Other research shows that lack of power may engender hopelessness and exacerbate stress. Studies that focus on these concepts could help explicate phenomenological and etiological aspects of suicide among marginalized and disadvantaged sub-populations.

Community Characteristics: Rural vs. Urban

Consistently, suicide rates are higher in rural areas than in urban areas (see Chapter 2). In China, the rate is two to five times greater in the rural regions (Ji et al., 2001; Jianlin, 2000; Phillips et al., 1999; Yip, 2001). Young Chinese women kill themselves three times more often in rural areas than in urban areas (Ji et al., 2001). This same trend has also been documented in young males in Australia (Wilkinson and Gunnell, 2000). Even among Greek adolescents where the suicide rate is relatively low, urban areas reported significantly lower suicide rates than rural areas (Beratis, 1991). In the Ukraine, suicide is also more frequent in rural areas and in industrially developed regions than in the cities (Kryzhanovskaya and Pilyagina, 1999). Over time in some countries, the effects of rural– urban residence are changing. In Japan, for example, the discrepancy between suicide rates in rural and urban districts increased from 1975 to 1985 but declined in subsequent years (Goto et al., 1994).

Social Changes and Suicide

From the beginnings of the social science study of suicide rates, massive social change, especially that evidenced by the rise of the industrial age, has been implicated as a major cause of rising suicide rates (Masaryk, 1970; Porterfield, 1952). Not surprising then, is the recent decrease in suicide in many Western European countries and the contrasting increase in Eastern European countries (Sartorius, 1995). The rates in Russia during the post-Soviet era have increased, in keeping with an overall increase in age-adjusted mortality and morbidity. Age-standardized suicide rates have almost doubled between 1970 and 1995 in Latvia (Kalediene, 1999). In the Ukraine, the suicide rate increased by 57 percent between 1988 and

1997 (Kryzhanovskaya and Pilyagina, 1999). However, during Perestroika in Russia (1984 to 1990), suicide rates declined by approximately 32 percent for males and 19 percent for females (Varnik et al., 1998). The decrease in female suicide was the same as seen in the rest of Europe, whereas the male decrease in suicide rate was 3.8 times that observed in other European countries. This large decrease in Russian male suicides coincided with a national, multi-pronged anti-alcoholism campaign over the same period. In this way, social circumstances interacted to provide increased hope for economic prosperity and social freedoms, with significantly reduced access to alcohol, creating a period associated with the greatest decrease in male suicide rates across the globe in the last 20 years (Wasserman and Varnik, 2001).

Suicide rates have declined in the Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) since 1986, which marked the onset of turbulent social change (Varnik et al., 1994). Rancans and colleagues (2001) determined that the rapid swings in the suicide rate in Latvia between 1980 and 1998 could not be explained by the changing employment rate, a sudden drop in the GDP, or a rapid increase in first-time alcohol psychosis. Makinen (2000) concludes that, while suicide and social processes in Eastern Europe during recent periods of social change are clearly linked, there remain complexities regarding the mechanisms and the specific aspects of the social change that may affect suicide rates.

LaVecchi et al. (1994) analyzed World Health Organization data from 1955–1989 for 57 countries and suggested that trends are decreasing in many parts of the less developed world including Latin America and Asia (with the exception of Sri Lanka). Others contend that suicide rates have increased in less developed countries or among particular segments of the population in these countries (Makinen, 1997). For example, the rate of suicide in Sri Lanka has risen from modest levels to one of the highest in the world over the last 50 years (Marecek, 1998). In Singapore, the last 10 years shows a greater disparity in male and female suicide rates. Prior to this time, the gender gap had diminished, and the current discrepancy appears to result from decreasing rates among women rather than any real change in male suicide levels (Parker and Yap, 2001). Micronesia witnessed a spike among adolescents and youth in the 1970s and 1980s. Researchers attributed this “epidemic” to vast social changes associated with modernization and globalization, which resulted in the breakdown of traditional values and practices and the development of “normlessness” or anomie, especially among adolescents (Rubinstein, 1983). In Western Samoa, for example, the rise in suicide rates since 1970 has been hypothesized to result from rising expectations among adolescents in the context of fading opportunities due to Western Samoa’s peripheral position in the world economy (Macpherson and Macpherson, 1987). In China, most re-

cent data from the Chinese government for 2000 show a significant fall in suicide rate from 23 per 100,000 to 17 per 100,000.

CHALLENGES

Cross-National Differences: Real or Artifact?

Interpretation of cross-national suicide rates are subject to several limitations. First, different countries may assign different meaning and classification to the acts. Kelleher et al. (1998) report that countries with religious sanctions against suicide were less likely to report their suicide rates to the World Health Organization, and on average, their reported rates were lower than for countries without sanctions.2 In India, suicide rates may be misrepresented due to traditional and unique cultural practices such as “dowry death,” which is a category of deaths of young married women including both homicide and suicide following from intense coercion for payment of unpaid or additional dowry. It may be difficult to differentiate homicide from suicide in the investigation of such deaths (Khan and Ray, 1984; Leslie, 1998). Second, difference among countries may reflect the capacity of the emergency health care system to respond rather than differences in the intent of the individuals. For example, the high rate of suicide among young Chinese women may result from the lethality of available means in the face of limited treatment availability. Women living on farms in China often have ready access to extremely toxic pesticides. It is often not possible to obtain emergency treatment after these chemicals are ingested in an impulsive moment. Thus, cases that might end up as suicide attempts in the United States are fatal in China. Difference in the demographics of suicide attempts and completions between counties may reflect these artifacts of infrastructure rather than psychological or biological differences (Ji et al., 2001). Third, the organization and functioning of medico-legal officials across countries has long been thought to produce artifactual differences even between similar countries such as Britain and Scotland (Barraclough, 1972). Most developing societies lack registries and expertly trained officials to record suicide. Further, there are cross-national differences in the underlying logic of classifications systems. In India, for example, the classification scheme focuses on social stressors rather than psychopathology. In 1997, only 4.9 percent of all suicides were attributed to mental disorders, while other causes were cited for the remaining 95.1 percent (e.g., family problems (18.4 percent), love affairs (3.7 percent), poverty (3.4 percent)) (Gov-

ernment of India, 1999). Phillips and colleagues (1999) suggest that the high suicide rates in China might be due to lower deliberate miscalculations of rates there than in other countries where suicide is illegal or can elicit serious consequences for families.

Integrating Approaches

Individual and Aggregate Studies

Studies that integrate the events at an individual level with events at an aggregate level can be extremely valuable to the understanding of suicide risk. These studies are scarce. The few that have been done suggest that contextual level findings do not simply reflect summed individual level effects. For example, in one study in the United States, the influence of social and cultural characteristics at the county level (a lower level of aggregation) was not as strongly associated with suicide rates as at the county group level (a higher level of aggregation; Pescosolido and Mendelsohn, 1986). Theoretical and methodological barriers impede understanding how individuals facing similar personal crises respond differently depending on the social and cultural context in which they live their lives. For example, even with the classic findings regarding religion, it is essential to document whether it is only the Catholics in areas with high representation of Catholics who are “protected” from suicidal risk, whether the social context exerts a protective effect across the region, and whether being a member of a different group results in greater suicidal risk. Appendix A illustrates an approach that can be used to address some of these issues. As described in greater detail there, a breakdown of suicide rate by county shows geographic distributions. Using a spatial distribution of Bayes estimates reveals outliers, that is, counties that are unlike those surrounding them. For example, in the western United States and Alaska where suicide rates are typically high, a few counties have Bayes estimates that are consistent with the national average. Similarly, in the central United States where there is a high concentration of counties with the lowest suicide rates, there are also a few counties that exhibit the highest suicide rates. Identification of these spatial anomalies and examining the particular characteristics that account for them can be a fruitful area for further research.

A Biopsychosocial Understanding

The interactions between social environment and general health are well documented, and it is clear from the evidence that the mechanism goes beyond access to health care or exposure to environmental toxins

(IOM, 2001). Poverty, discrimination, and social isolation are associated with poor health. Links between mental illness and culture, race, and ethnicity also have been described (US DHHS, 1999; US DHHS, 2001). Risk factors are thought to involve everything from genetic variation in metabolism to the adverse effects of poverty and discrimination. These links are likely to extend to suicide, but the evidence is limited.

As described in this report, many factors impact the risk of suicide: social, psychological, and biological. Box 6-2 describes efforts to disentangle the roles of these factors among the Old Order Amish. Mental illness, personality and temperament, societal and individual experiential factors like economic depression, interpersonal loss, societal violence and childhood trauma, and the social context for these experiences are all important to consider in assessment of any individual. Psychic distress may be a common thread across cultures and diagnoses for those who are

|

BOX 6-2 In studying 26 suicides over a 100 year period among the Amish of Pennsylvania, Egeland and Sussex (1985) found that suicides clustered in four primary pedigrees with heavy loading for bipolar, unipolar, and affective illnesses. Yet attempts to verify a specific genetic link have failed (Egeland et al., 1987; Kelsoe et al., 1989). While still cited as evidence for a genetic component for affective disorders and suicide (e.g., Roy, 1993), the specific link for inheritance among the Amish is unresolved. To understand suicide among the Amish, it is important to consider their social and cultural circumstances. While the Amish have rates of bipolar illness similar to the non-Amish population (Egeland et al., 1983), Amish communities have a high level of social integration. Consequently, individuals are at greater risk if their social support networks are affected or if the larger community faces crises. Kraybill et al. (1986) suggest that suicides clustered during times when the community as a whole was under stress from outside social pressure resulting from the modernization of agriculture and schooling. This is further supported by the socio-demographic profiles of the suicides. While the gender distribution (3 males to 1 female) did not vary from the surrounding area, they were predominant among the middle age groups, those most likely to confront the outside pressures. There were no suicides among youth (under 18). Elders (over 59) were also at much lower risk in comparison with the surrounding population. While these findings need to be interpreted cautiously because of the small number of cases, these patterns suggest the utility of and need for integrated biological, genetic, and social/behavioral science research. |

suicidal. Despite years of research, we cannot predict who will commit suicide. African-American women, for example, have many risk factors including discrimination, poverty, exposure to violence, etc., but also have one of the lowest suicide rates. Why do some people with such adversity not commit suicide while others do? An understanding of this seemingly paradoxical relationship through biopsychosocial research is critical to the advancement of suicidology. Suicide can only be understood by integrating approaches that have historically remained distinct.

FINDINGS

-

Culture strongly influences how individuals view suicide. Cultural values and social structures largely determine the type and degree of both stressors and support, availability of means and access to treatment, and social prescriptions or proscriptions concerning suicidal behavior.

-

Across cultures, family cohesion and support acts as a buffer against suicidality; parenthood protects against suicide, particularly for women. Divorced and never-married status generally increases suicide risk, especially among men. Social support and various types of religious involvement and beliefs are protective against suicide.

-

Unemployment and low socioeconomic status generally increase suicide risk. Societal-wide economic and social changes also influence the incidence of suicide. Social change can create economic hardship, increase family discord, result in migration or separation of families and friends, increase use of alcohol, etc. Investigation into the complex interaction of the macro-social and individual variables is valuable. Yet there are few studies that integrate the events at an individual level with events at an aggregate level.

The field requires additional research on the interactions of individual and aggregate level variables. Since biological, psychosocial, and sociological factors all amplify or buffer the risk of suicide, future research needs to incorporate interdisciplinary, multi-level approaches. Studies on the interactions of genetics and psychosocial, socio-political, and socioeconomic context, for example, are necessary.

Use of data from developing societies that comprise more than 80 percent of the world’s population and look somewhat different than United States data may provide a more representative picture for poor and middle income countries. Contrasts among international

suicide data also offer important insights into the influence of cultural/macro-social contexts on suicide.

-

Cultures vary in their stigma against suicide, in treatment availability, in classifications of suicide and mental illness, and in the infrastructure for monitoring death by suicide. These differences render cross-national comparisons of suicidal behavior difficult.

New approaches and assessments are needed to ensure that social epidemiological findings are sufficiently powerful in predicting suicide to overcome classification differences that arise from diverse understandings and recording of behaviors that may be considered suicides. In addition, research based on ethnography and other qualitative methods provides greater detail about the setting, conditions, process, and outcome of suicide and should be developed to deepen and make more valid psychological autopsy studies.

REFERENCES

Abbey A, Andrews FM. 1985. Modeling the psychological determinants of life quality. Social Indicators Research, 16(1): 1-34.

Allebeck P, Allgulander C, Fisher LD. 1988. Predictors of completed suicide in a cohort of 50,465 young men: Role of personality and deviant behaviour. British Medical Journal, 297(6642): 176-178.

Allebeck P, Varla A, Kristjansson E, Wistedt B. 1987. Risk factors for suicide among patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 76(4): 414-419.

Andriolo KR. 1998. Gender and the cultural construction of good and bad suicides. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 28(1): 37-49.

Appleby L, Cooper J, Amos T, Faragher B. 1999. Psychological autopsy study of suicides by people aged under 35. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175: 168-174.

Arensman E, Kerkhof AJ, Hengeveld MW, Mulder JD. 1995. Medically treated suicide attempts: A four year monitoring study of the epidemiology in The Netherlands. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 49(3): 285-289.

Arnetz BB, Horte LG, Hedberg A, Theorell T, Allander E, Malker H. 1987. Suicide patterns among physicians related to other academics as well as to the general population. Results from a national long-term prospective study and a retrospective study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 75(2): 139-143.

Ausenda G, Lester D, Yang B. 1991. Social correlates of suicide and homicide in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 240(4-5): 301-302.

Azhar MZ, Varma SL, Dharap AS. 1994. Religious psychotherapy in anxiety disorder patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90(1): 1-3.

Barefoot JC, Brummett BH, Helms MJ, Mark DB, Siegler IC, Williams RB. 2000. Depressive symptoms and survival of patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62(6): 790-795.

Barraclough BM. 1972. Are the Scottish and English suicide rates really different? British Journal of Psychiatry, 120(556): 267-273.

Bat-Aion N, Levy-Shiff R. 1993. Children in war: Stress and coping reactions under the threat of scud missile attacks and the effect of proximity. In: Leavitt LA, Fox NA, Editors. The Psychological Effects of War and Violence on Children. (pp. 143-161). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Batson CD, Schoenrade P, Ventis WL. 1993. Religion and the Individual: A Social-Psychological Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beratis S. 1991. Suicide among adolescents in Greece. British Journal of Psychiatry, 159: 515-519.

Bille-Brahe U. 1987. Suicide and social integration. A pilot study of the integration levels in Norway and Denmark. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplement, 336: 45-62.

Black A Jr. 1990. Jonestown—two faces of suicide: A Durkheimian analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20(4): 285-306.

Boor M. 1981. Effects of United States presidential elections on suicides and other causes of death. American Sociological Review, 46: 616-618.

Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD. 2001. Adolescent suicide attempts: Risks and protectors. Pediatrics, 107(3): 485-493.

Borowsky IW, Resnick MD, Ireland M, Blum RW. 1999. Suicide attempts among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: Risk and protective factors. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153(6): 573-580.

Braam AW, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Smit JH, van Tilburg W. 1997a. Religiosity as a protective or prognostic factor of depression in later life: Results from a community survey in The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 96(3): 199-205.

Braam AW, Beekman AT, van Tilburg TG, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg W. 1997b. Religious involvement and depression in older Dutch citizens. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 32(5): 284-291.

Breault KD. 1986. Suicide in America: A test of Durkheim’s theory of religious and family integration, 1933-1980. American Journal of Sociology, 92(3): 628-656.

Breed W. 1963. Occupational mobility and suicide among white males. American Sociological Review, 28: 179-188.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Liotus L, Schweers J, Balach L, Roth C. 1994. Familial risk factors for adolescent suicide: A case-control study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 89(1): 52-58.

Brummett BH, Babyak MA, Barefoot JC, Bosworth HB, Clapp-Channing NE, Siegler IC, Williams RB Jr, Mark DB. 1998. Social support and hostility as predictors of depressive symptoms in cardiac patients one month after hospitalization: A prospective study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 60(6): 707-713.

Cantor CH, Slater PJ, Najman JM. 1995. Socioeconomic indices and suicide rate in Queensland. Australian Journal of Public Health, 19(4): 417-420.

Carbonell DM, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM. 1998. Risk and resilience in late adolescence. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 15(4): 251-272.

Cavanagh JT, Owens DG, Johnstone EC. 1999. Life events in suicide and undetermined death in south-east Scotland: A case-control study using the method of psychological autopsy. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34(12): 645-650.

Chan KP, Hung SF, Yip PS. 2001. Suicide in response to changing societies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 10(4): 777-795.

Charlton J. 1995. Trends and patterns in suicide in England and Wales. International Journal of Epidemiology, 24 (Suppl 1): S45-S52.

Chuang HL, Huang WC. 1996. A reexamination of “Sociological and economic theories of suicide: A comparison of the U.S.A. and Taiwan”. Social Science and Medicine, 43(3): 421-423.

Colasanto D, Shriver J. 1989. Mirror of America: Middle-aged face marital crisis. Gallup Report, No. 284, 34-38.

Conger RD, Elder GHJ, Lorenz FO, Conger KJ, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Huck S, Melby JN. 1990. Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(3): 643-656.

Conrad N. 1991. Where do they turn? Social support systems of suicidal high school adolescents. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 29(3): 14-20.

Conway K. 1985-1986. Coping with the stress of medical problems among Black and White elderly. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 21(1): 39-48.

Coser RL, Coser L. 1979. Jonestown as perverse utopia. Dissent, 26: 158-163.

Counts DA. 1987. Female suicide and wife abuse: A cross-cultural perspective. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 17(3): 194-204.

Crombie IK. 1990. Can changes in the unemployment rates explain the recent changes in suicide rates in developed countries? International Journal of Epidemiology, 19(2): 412-416.

D’Attilio JP, Campbell BM, Lubold P, Jacobson T, Richard JA. 1992. Social support and suicide potential: Preliminary findings for adolescent populations. Psychological Reports, 70(1): 76-78.

de Castro EF, Martins I. 1987. The role of female autonomy in suicide among Portuguese women. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 75(4): 337-343.

de Castro EF, Pimenta F, Martins I. 1988. Female independence in Portugal: Effect on suicide rates. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 78(2): 147-155.

De Wilde EJ, Kienhorst CW, Diekstra RF, Wolters WH. 1994. Social support, life events, and behavioral characteristics of psychologically distressed adolescents at high risk for attempting suicide. Adolescence, 29(113): 49-60.

Donahue MJ. 1995. Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues, 51(2): 145-160.

Drake RE, Gates C, Cotton PG. 1986. Suicide among schizophrenics: A comparison of attempters and completed suicides. British Journal of Psychiatry, 149: 784-787.

Durkheim E. 1897/1951. Translated by JA Spaulding and G Simpson. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. New York: Free Press.

Egeland JA, Gerhard DS, Pauls DL, Sussex JN, Kidd KK, Allen CR, Hostetter AM, Housman DE. 1987. Bipolar affective disorders linked to DNA markers on chromosome 11. Nature, 325(6107): 783-787.

Egeland JA, Hostetter AM, Eshleman SK 3rd. 1983. Amish Study, III: The impact of cultural factors on diagnosis of bipolar illness. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(1): 67-71.

Egeland JA, Sussex JN. 1985. Suicide and family loading for affective disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association, 254(7): 915-918.

Ellis JB, Smith PC. 1991. Spiritual well-being, social desirability and reasons for living: Is there a connection? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 37(1): 57-63.

Eskin M. 1995. Suicidal behavior as related to social support and assertiveness among Swedish and Turkish high school students: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(2): 158-172.

Ferrada-Noli M. 1997. Social psychological variables in populations contrasted by income and suicide rate: Durkheim revisited. Psychological Reports, 81(1): 307-316.

Ferrada-Noli M, Asberg M. 1997. Psychiatric health, ethnicity and socioeconomic factors among suicides in Stockholm. Psychological Reports, 81(1): 323-332.

Freud A, Burlingham D. 1943. War and Children. New York: International Universities Press.

Garbarino J, Kostelny K. 1993. Children’s response to war: What do we know? In: Leavitt LA, Fox NA, Editors. The Psychological Effects of War and Violence on Children. (pp. 23-39). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gehlot PS, Nathawat SS. 1983. Suicide and family constellation in India. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 37(2): 273-278.

Giddens A. 1964. Suicide, attempted suicide and the suicidal threat. Man: A Record of Anthropological Science, 64: 115-116.

Gorsuch RL. 1995. Religious aspects of substance abuse and recovery. Journal of Social Issues, 51(65-83).

Goto H, Nakamura H, Miyoshi T. 1994. Epidemiological studies on regional differences in suicide mortality and its correlation with socioeconomic factors. Tokushima Journal of Experimental Medicine, 41(3-4): 115-132.

Government of India, National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. 1999. Accidental Death and Suicide in India 1997.

Guiao IZ, Esparza D. 1995. Suicidality correlates in Mexican American teens. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 16(5): 461-479.

Hamermesh DS, Soss NM. 1974. An economic theory of suicide. Journal of Political Economy, 82(1): 83-98.

Hasselback P, Lee KI, Mao Y, Nichol R, Wigle DT. 1991. The relationship of suicide rates to sociodemographic factors in Canadian census divisions. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 36(9): 655-659.

Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. 2001. Suicide in doctors: A study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979-1995. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55(5): 296-300.

Hawton K, Houston K, Shepperd R. 1999. Suicide in young people. Study of 174 cases, aged under 25 years, based on coroners’ and medical records . British Journal of Psychiatry, 175: 271-276.

Heikkinen M, Aro H, Lonnqvist J. 1994. Recent life events, social support and suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplement, 377: 65-72.

Heikkinen ME, Isometsa ET, Marttunen MJ, Aro HM, Lonnqvist JK. 1995. Social factors in suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6): 747-753.

Herth KA. 1989. The relationship between level of hope and level of coping response and other variables in patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 16(1): 67-72.

Hovey JD. 1999. Moderating influence of social support on suicidal ideation in a sample of Mexican immigrants. Psychological Reports, 85(1): 78-79.

Hovey JD. 2000a. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among Central American immigrants. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 30(2): 125-139.

Hovey JD. 2000b. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6(2): 134-151.

Hoyer G, Lund E. 1993. Suicide among women related to number of children in marriage. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(2): 134-137.

Hutchinson GA, Simeon DT. 1997. Suicide in Trinidad and Tobago: Associations with measures of social distress. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 43(4): 269-275.

Iga M. 1996. Cultural aspects of suicide: The case of Japanese oyako shinju (parent-child suicide). Archives of Suicide Research, 2: 87-102.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Health and Behavior: The Interplay of Biological, Behavioral, and Societal Influences. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jamison KR. 1995. An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness. New York: A.A. Knopf.

Ji J, Kleinman A, Becker AE. 2001. Suicide in contemporary China: A review of China’s distinctive suicide demographics in their sociocultural context. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 9(1): 1-12.

Jianlin J. 2000. Suicide rates and mental health services in modern China. Crisis, 21(3): 118-121.

Kalediene R. 1999. Time trends in suicide mortality in Lithuania. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica , 99(6): 419-422.

Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Rita H. 1987. Mortality after bereavement: A prospective study of 95,647 widowed persons. American Journal of Public Health, 77(3): 283-287.

Kaslow NJ, Thompson MP, Meadows LA, Jacobs D, Chance S, Gibb B, Bornstein H, Hollins L, Rashid A, Phillips K. 1998. Factors that mediate and moderate the link between partner abuse and suicidal behavior in African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(3): 533-540.

Kelleher MJ, Chambers D, Corcoran P, Williamson E, Keeley HS. 1998. Religious sanctions and rates of suicide worldwide. Crisis, 19(2): 78-86.

Kelleher MJ, Daly M. 1990. Suicide in Cork and Ireland. British Journal of Psychiatry, 157: 533-538.

Kelsoe JR, Ginns EI, Egeland JA, Gerhard DS, Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Pauls DL, Long RT, Kidd KK, Conte G, et al. 1989. Re-evaluation of the linkage relationship between chromosome 11p loci and the gene for bipolar affective disorder in the Old Order Amish. Nature, 342(6247): 238-43.

Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. 1997. Religion, psychopathology, and substance use and abuse: A multimeasure, genetic-epidemiologic study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(3): 322-329.

Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C, Chen J. 1996. The relation of religious preference and practice to depressive symptoms among 1,855 older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51(6): P301-P308.

Kennedy HG, Iveson RC, Hill O. 1999. Violence, homicide and suicide: Strong correlation and wide variation across districts. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175: 462-466.

Khan MM, Reza H. 2000. The pattern of suicide in Pakistan. Crisis, 21(1): 31-35.

Khan MZ, Ray R. 1984. Dowry death. Indian Journal of Social Work, 45(3): 303-315.

Kinnunen U, Pulkkinen L. 1998. Linking economic stress to marital quality among Finnish marital couples: Mediator effects. Journal of Family Issues, 19(6): 705-724.

Kirk AR, Zucker RA. 1979. Some sociopsychological factors in attempted suicide among urban black males. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 9(2): 76-86.

Kirmayer LJ, Boothroyd LJ, Hodgins S. 1998. Attempted suicide among Inuit youth: Psychosocial correlates and implications for prevention. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(8): 816-822.

Kirmayer LJ, Malus M, Boothroyd LJ. 1996. Suicide attempts among Inuit youth: A community survey of prevalence and risk factors. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 94(1): 8-17.

Kitagawa JM. 1989. Buddhist medical history. In: Sullivan LE, Editor. Healing and Restoring—Health and Medicine in the World’s Religious Traditions. New York: Macmillan.

Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Pieper C, Meador KG, Shelp F, Goli V, DiPasquale B. 1992. Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149(12): 1693-1700.

Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, George LK, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. 1997. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 27(3): 233-250.

Koenig HG, Ford S, George LK, Blazer DG, Meador KG. 1993. Religion and anxiety disorder: An examination and comparison of associations in young, middle-aged and elderly adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7: 321-342.

Koenig HG, George LK, Meador KG, Blazer DG, Ford SM. 1994. The relationship between religion and alcoholism in a sample of community dwelling adults. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 45: 225-231.

Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL. 1998. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(4): 536-542.

Koenig HG, George LK, Siegler IC. 1999. The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. Gerontologist, 28: 303-310.

Koenig HG, Hays JC, George LK, Blazer DG, Larson DB, Landerman LR. 1997. Modeling the cross-sectional relationships between religion, physical health, social support, and depressive symptoms. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 5(2): 131-144.

Koenig HG, Larson DB, Weaver AJ. 1998. Research on religion and serious mental illness. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 80: 81-95.

Kotler M, Iancu I, Efroni R, Amir M. 2001. Anger, impulsivity, social support, and suicide risk in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(3): 162-167.

Kposowa AJ. 2000. Marital status and suicide in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 54(4): 254-261.

Kposowa AJ. 2001. Unemployment and suicide: A cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Psychological Medicine, 31(1): 127-138.

Kraybill D, Hostetter J, Shaw D. 1986. Suicide patterns in a religious subculture: The Old Order Amish. International Journal of Moral and Social Studies, 1: 249-263.