4

State Policies on Including, Accommodating, and Reporting Results for Students with Special Needs

As stated earlier, one objective for the workshop was to learn more about states’ policies for reporting results of accommodated tests. Given the mandates of recent legislation, states have accumulated a good deal of experience with including and accommodating students with special needs and reporting their results. NAEP’s stewards were interested in hearing about states’ policies and the lessons learned during the policy development process. The goal was to learn about findings from research and surveys as well as to hear firsthand accounts of states’ experiences. This information is useful for NAEP’s stewards as they formulate new policy for NAEP and is especially relevant, given the comparisons between NAEP and state assessment results expected to be required by law.

This chapter summarizes remarks made by the second panel of workshop speakers. This panel included three researchers who have conducted surveys of states’ reporting policies and two representatives from state assessment programs. Martha Thurlow, director of the National Center on Educational Outcomes at the University of Minnesota, reported on findings from her research on states’ policies and practices for including and accommodating students with disabilities in statewide assessments and reporting their scores. Researchers with George Washington University’s Center for Equity and Excellence in Education (CEEE) have conducted similar studies on states’ policies for English-language learners. One study, designed to collect information on policies for 2000–2001, is currently under way. Another study, examining policies for 1998–1999, has been published

(Rivera, Stansfield, Scialdone, and Sharkey, 2000). Lynne Sacks and Laura Golden, researchers with the CEEE, gave an overview of findings from the earlier study and highlighted preliminary findings from the study currently under way. This chapter summarizes major findings from the surveys and adds comments from the personal experiences of the two state assessment directors, Scott Trimble, director of assessment for Kentucky, and Phyllis Stolp, director of development and administration, student assessment programs for Texas. Trimble’s and Stolp’s comments about the policies and experiences in their respective states are described in further detail in Chapter 5. The chapter concludes with discussion about the complications involved in interpreting results that include scores for accommodated test takers.

INCLUSION AND ACCOMMODATION POLICIES

As background, the speakers first discussed their research findings regarding states’ inclusion and accommodation policies. Martha Thurlow discussed states’ policies for including and accommodating students with disabilities; Lynne Sacks and Laura Golden provided similar information about states’ policies for English-language learners.

Policies for Students with Disabilities

According to Thurlow, all states now have a policy that articulates guidelines for including and accommodating students with disabilities. These policies typically acknowledge the idea that some changes in administration practices are acceptable because they do not alter the construct tested, while others are unacceptable because they change the construct being assessed. Thurlow noted that the majority of states (n=39) make a distinction between acceptable and unacceptable accommodations, but they use a variety of terminology to do so (e.g., accommodation vs. modification, allowed vs. not allowed, standard vs. nonstandard, permitted vs. nonpermitted, and reportable vs. not reportable). For students with disabilities, accommodations are determined by the IEP teams, and they can be categorized as changes in the administration setting or timing (e.g., one-on-one administration, extended time), changes in test presentation (e.g., large print, Braille, read aloud), or changes in the mode for responding to the test (e.g., dictating responses, typing instead of handwriting responses, marking answers in the test booklet).

Policies for English-Language Learners

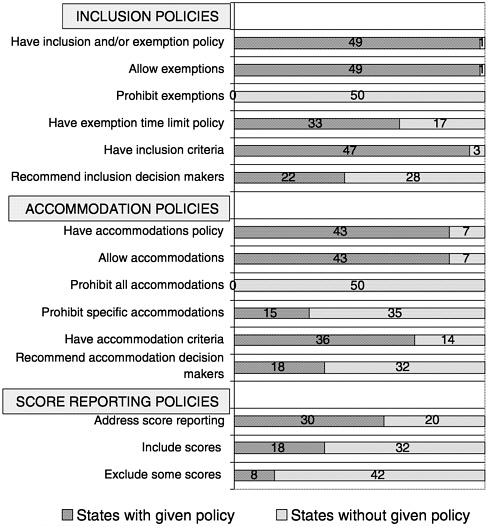

In their presentations, Lynne Sacks and Laura Golden reported that all but one of the states have policies that articulate guidelines for including English-language learners in assessments. Forty-three states have policies for providing accommodations to English-language learners. All of these states allow English-language learners to test with accommodations, and 15 states expressly prohibit certain accommodations. This information is summarized in Figure 4–1.

Accommodations for English-language learners can be classified as lin

FIGURE 4–1 States’ Policies for Including and Accommodating English-Language Learners in State Assessments—Preliminary Survey Findings (2000–2001).

SOURCE: Golden and Sacks (2001).

guistic or nonlinguistic. Nonlinguistic accommodations are those that have been traditionally offered to students with disabilities, such as extended time or testing in a separate room. Linguistic accommodations can be further categorized as English-language and native-language. English-language accommodations assist the student with testing in English and include adjustments such as repeating, simplifying, or clarifying test directions in English; the use of English-language glossaries; linguistic simplification of test items; and oral administration. Native-language accommodations allow the student to test in his or her native language and include use of a bilingual dictionary or a translator; oral administration in the student’s native language; use of a translated version of the test; and allowing the student to respond in his or her native language. Results from the research by Sacks and Golden show that states offer more nonlinguistic than linguistic accommodations to English-language learners.

Decision making about providing accommodations for English-language learners is complicated by the fact that these students do not have IEPs, which means that there is no common basis for making these decisions. States vary with respect to who makes the decision and how it is made. The 1998–1999 survey results indicated that most often the decision was simply to let the student use whatever accommodations he or she routinely uses in the classroom situation (Rivera et al., 2000).

REPORTING POLICIES

Panel three speakers also described states’ policies for reporting results for individuals who received accommodations. There are two distinct issues related to reporting such results-which students’ scores are included in overall reports of test results and whether or not group-level (or disaggregated) results are reported. Each issue is taken up separately below.

Policies for Reporting Overall Results

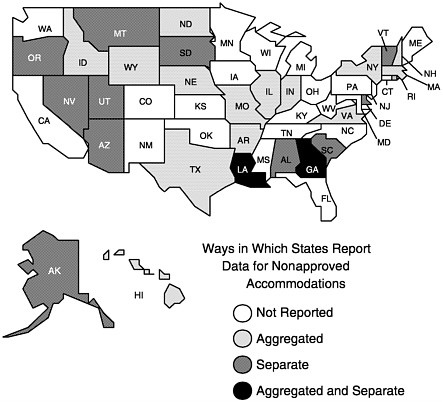

Thurlow’s findings indicate that states’ policies for reporting results for students with disabilities tend to differ depending on whether students received approved or nonapproved accommodations. Nearly all states (n=46) plan to report results for students with disabilities who use approved accommodations by aggregating those scores with scores of other test takers. However, methods and reporting policies for students using nonapproved accommodations vary considerably among states. Thurlow’s findings indicated that 25 states planned to report scores of students who

used nonapproved accommodations. Eleven of these states will aggregate these scores with other scores; twelve will report these scores separately from other scores; and two plan to report both ways.

A variety of policies are in effect in the remaining 25 states. In three states, students who use nonapproved accommodations will be assigned the lowest possible score or a score of zero. Six states indicated they plan to “count” (n=3) or “not count” (n=3) scores for examinees who use nonapproved accommodations, but these states did not explicitly indicate their policies for reporting such scores. Two states had not yet finalized their reporting policies at the time of the survey. Fourteen states have other plans for reporting scores, and many of these indicated that nonapproved accommodations were not allowed or that students who needed these accommodations would take the state’s alternate assessment. These findings are displayed in Figure 4–2 and Table 4–1 and are more fully described in Thurlow (2001a).

FIGURE 4–2 States’ Policies for Reporting Scores from Tests Taken with Nonapproved Accommodations (2001).

SOURCE: Thurlow (2001a).

TABLE 4–1 Responses of State Directors of Special Education to NCEO On-line Survey

|

State |

Approved Accommodations |

Nonapproved Accommodations |

|

Alabama |

No Decision |

Separate |

|

Alaska |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Arizona |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Arkansas |

Separate |

Aggregated |

|

California |

Aggregated |

Counted |

|

Colorado |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

Connecticut |

Aggregated |

No Decision |

|

Delaware |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Florida |

Separate |

Other |

|

Georgia |

Aggregated, Separate |

Aggregated, Separate, Counted |

|

Hawaii |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Idaho |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Illinois |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Indiana |

Aggregated, Separate |

Lowest Score |

|

Iowa |

Aggregated |

Not Counted |

|

Kansas |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Kentucky |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

Louisiana |

Aggregated |

Aggregated, Separate |

|

Maine |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

Maryland |

Other |

Other |

|

Massachusetts |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Michigan |

Aggregated |

No Decision |

|

Minnesota |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

Mississippi |

Aggregated |

Not Counted |

|

Missouri |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Montana |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Nebraska |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Nevada |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

New Hampshire |

Aggregated |

Lowest Score |

|

New Jersey |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

New Mexico |

Aggregated, Separate |

Other |

|

New York |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

North Carolina |

Aggregated |

Not Counted |

|

North Dakota |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

|

Ohio |

Aggregated |

Counted |

|

Oklahoma |

Aggregated, Separate |

Other |

|

Oregon |

Aggregated |

Separate |

|

Pennsylvania |

Aggregated |

Other |

|

Rhode Island |

Aggregated |

Aggregated |

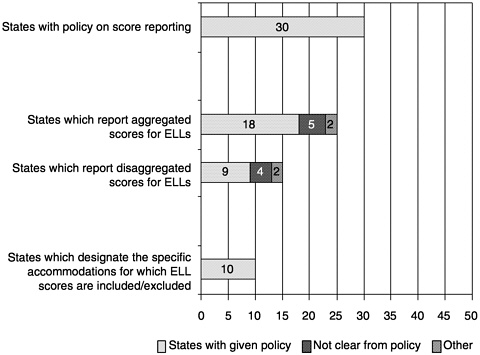

Sacks’ and Golden’s findings indicate that not all states have policies about reporting results of English-language learners, although the number of states with policies has increased since the 1998–1999 survey. Their most recent findings show that 30 states now have policies, as compared to only 17 for the earlier survey. Of these 30 states, 18 aggregate the scores for English-language learners with results for other test takers. The presenters commented that they did not yet have information on how reporting is handled in the other states. This information is portrayed in Figures 4–2 and 4–3.

Policies and Concerns About Reporting Group-Level Results

The federal legislation passed in January 2002 makes states accountable for the yearly progress of English-language learners and for students with disabilities, thus requiring the reporting of disaggregated results for both groups. This requirement was not in place at the time the various surveys were conducted, and few states indicated that they report disaggregated results by disability status or by limited-English-proficiency status. The topic of reporting disaggregated results provoked considerable discussion at the workshop and presenters, discussants, and participants commented about a number of issues related to group-level reporting.

FIGURE 4–3 States’ Policies for Reporting Results for English-Language Learners who Receive Accommodations on State Assessments—Preliminary Survey Findings (2000–2001).

SOURCE: Golden and Sacks (2001).

The first issue concerns the meaningfulness of disaggregated results. Eugene Johnson, chief psychometrician at the American Institutes for Research, and Jamal Abedi, professor at UCLA, pointed out that the categories of English-language learners and students with disabilities are very broad and comprise individuals with diverse characteristics. The group of English-language learners includes students who differ widely with respect to their native languages and their levels of proficiency with English. Similarly, the group of students with disabilities encompasses individuals with a wide variety of special needs, such as learning disabilities, visual impairments, and hearing impairments. With such within-group diversity, it is difficult to know what conclusions can be drawn about any reported group-level statistics.

Other issues arise because of the small sample sizes that result when data are disaggregated. These small sample sizes affect the level of confidence one can have in the results because statistics based on small sample sizes are less reliable and less stable. This is true for the summary statistics

about test performance as well as for the percentages and other statistics that summarize demographic characteristics. Scott Trimble pointed out that these concerns about reporting results based on small sample sizes have led Kentucky to implement several measures. The state plans to provide estimates of standard error on newer reports and has set a minimum sample size for reporting disaggregated results.1 Nevertheless, Trimble believes that many report users do not attend to standard error information. Johnson, who has served as consultant for numerous testing programs, added that interpreting standard error information for the lay public is so problematic that many programs simply resort to setting minimum sample sizes. According to Trimble, Kentucky does not report disaggregated data for any group that has 10 or fewer students. He added that while 10 seems to be a small number on which to base important decisions about a particular group of students, setting a higher minimum number would mean that a good deal of data could not be reported.

Another concern is the stability of group composition over time, an issue particularly important if the desire is to track and report valid trends for the various groupings. When the numbers are small, even slight changes in the composition of a group can produce large changes in the overall results. Such changes can occur, for instance, when geographical boundaries that make up the population of students attending a given school building are altered or when the guidelines for identifying students with special needs are refined. Hence, there may be changes in performance from one testing occasion to the next, but it is impossible to know whether they are the result of changes in the characteristics of the population or changes in the skill levels of the students.

Trimble recounted another problem that occurred in Kentucky in connection with disaggregation. For the state assessment, results are reported as achievement levels (novice, apprentice, proficient, and distinguished). It sometimes happens that all students in a particular population group score at the same level. When disaggregated results are reported for such a group, student scores are essentially disclosed, as the group’s composition can be easily identified. In Kentucky, this violates the state laws that prohibit producing reports that permit the identification of individual student scores. Kentucky now has a quality control check intended to prevent this.

FACTORS COMPLICATING THE INTERPRETATION OF REPORTED RESULTS

Several workshop speakers described complications that can affect the interpretation of data reported for students with disabilities and English-language learners. As the survey results showed, states’ accommodations policies vary considerably with respect to which types of accommodations are approved and nonapproved. Therefore, even if reports are confined to approved accommodations, the group of students actually included may differ from state to state, and the conditions of their testing may not be similar (disregarding for the moment the fact that the assessments also differ from state to state).

For example, consider the various ways accommodations might be provided and scores reported for students with a reading disability and Hispanic English-language learners taking a reading test. In state A, reported results could include scores for the general population testing under standard conditions, Hispanic English-language learners who took a translated Spanish version, and students with reading disabilities who received an oral administration. In state B, the oral administration and Spanish translation accommodations might be provided but considered nonapproved. Thus, unlike state A, overall score reports might not include results for these two accommodated groups. In state C, Hispanic English-language learners and students with reading disabilities may have received other types of approved accommodations (such as an English glossary for the English-language learners and extended time for the students with disabilities). Hence, like state A, their results might be included in the reports, but the scores were obtained under different conditions than in state A, conditions likely to affect performance and, consequently, the reported statistics. This variability in which accommodations are provided and which scores are included in reports complicates any attempt to make comparisons across states or between state results and NAEP (in addition to the problems posed by making comparisons of results based on different tests). This is true for reports of both aggregated and disaggregated results.

Another complication arises from states’ policies regarding accommodating students with temporary disabilities. Some states approve accommodations for students who have a short-term disabling condition (e.g., a broken arm) that incapacitates them from taking the test under standard conditions. Thus, group-level reports of results for those who received

accommodations may include scores for some general education students with temporary disabilities.

A third complication arises in connection with how students are identified as having a disability or as English-language learners. As Richard Durán, professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, pointed out, determinations about which students qualify as students with disabilities or as English-language learners are not made on the basis of empirically measurable, scientifically sound criteria. For students with disabilities, particularly those with learning disabilities or attention deficit disorder, the determination is often made only when they perform poorly in school. Similarly, a wide variety of methods are used for identifying students as English-language learners.

Durán is especially concerned about identification of English-language learners. He has found that the typical practice is to classify students as English-language learners if their proficiency in English is limited for the purposes of classroom learning. However, some states use a test to make the classification while others use the numbers of years of exposure to instruction in an English-speaking environment or other factors. Durán believes that determination of English-language learner status should be based on measured proficiency in English. He has found that it is not often done this way, in part because there are few tests of English proficiency and considerable disagreement about the quality of existing tests. This stems from the fact that there is no single theory on how to measure language proficiency. Tests vary across states as do the regulations about the number of years students are required to be in school before they must receive instruction only in English (e.g., in California the requirement is one year, but this varies across states).

The result of these inconsistencies is that the categories (i.e., English-language learner and students with disabilities) consist of heterogeneous populations. Some workshop participants thought that this problem could be overcome for students with disabilities by further refining the categories for reporting purposes, that is, categorizing by the nature of the disability or the type of accommodation provided. However, this would result in even smaller numbers of students in each category, and it would not resolve the problem of heterogeneous categories for English-language learners. These problems become more immediate with the newly implemented accountability measures that require disaggregated reporting of results for English-language learners and students with disabilities.