CHAPTER 7

INDUSTRIAL, GOVERNMENTAL, ACADEMIC, AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES IN MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING*

CHAPTER 7

INDUSTRIAL, GOVERNMENTAL, ACADEMIC, AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES IN MATERIALS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING

INTRODUCTION

The United States, with about one-twentieth of the world’s population, consumes more than one-third of the world’s mineral resources. However, although the American people have become accustomed to the ready availability of a great variety and quantity of material goods, the mineral-resource base from which many of the materials are derived is changing in character and accessibility. Private industry, our society’s institution for providing these material goods, has developed a remarkably successful system to keep pace with the ever-growing product demand. World trade and improved technology are both parts of this system. Thus, the U.S. must export products and/or resources to pay for raw material imports and, through continued scientific and technological improvements in materials production and application, compete effectively in world product markets.

About one-fifth of the U.S. gross national product originates in the extraction, refining, processing, and forming of materials other than food and fuel. Thus, the translation of raw materials into finished goods is a large and significant economic activity. Nevertheless, the public is not normally perceptive of the materials because of their ubiquitous nature and the fact that they are seldom products in their own right.

All materials pass through a number of stages from their extraction to utilization. At each stage, economic value is added and costs are incurred to pay for energy, production manpower, research manpower, and administration. In addition, costs are incurred in post-use disposal and recycling. The institution generally employed in our society for implementing this utilization of materials is private industry. Competing in the marketplace under ground rules established by society through its governmental bodies, private industry attempts to minimize the cost of materials utilization to produce quality goods that satisfy its customers and to provide a reasonable return on investment to its owners.

As discussed in earlier chapters, the concept of the materials cycle, or the physical flow of materials, is very useful for perceiving the interrelationships of the various stages of extraction, conversion, processing, fabrication or assembly, product utilization, and scrap disposal or recycling. The general characteristics of the materials flows, including related energy and waste flows, that would have to be taken into account in a quantitative

model are indicated in Figure 2.3 of Chapter 2.*

Materials are produced in commodity-oriented industries such as rubber, plastics, metals, glass, ceramics, cement, timber, and chemicals. Materials are consumed in product-oriented industries such as transportation, electronics, containers, lighting, and construction. The ultimate user, society itself, is concerned principally with the cost, performance, and functional value of products, and is only incidentally knowledgeable in the materials involved in their manufacture. Because of future prospects regarding changes in the character of the sources of traditional materials and the increasing utility of newer materials such as aluminum, electronic materials, and synthetic polymers—and the increasing potential for designing materials to provide desired engineering performance—it is important that appropriate attention be given to the continued development of the science and technology of materials. This evolving field, which already affects almost all of the capital and consumer goods that we are familiar with, promises to have a worthwhile influence on this nation’s future economic, aesthetic, and social well-being.

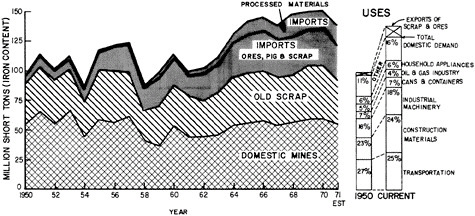

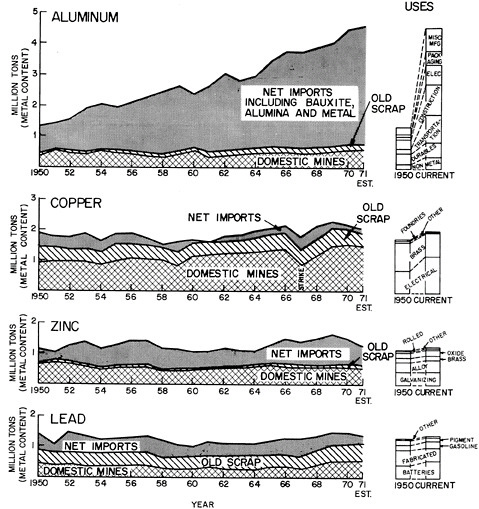

Regarding the existing relations between resource supplies and world trade, important changes are well underway and unmistakable. For example, a 1970 analysis1 reports that the U.S. has “rapidly deteriorating, and by now large,” deficits in trade with minerals and raw materials, and with manufactured materials such as steel, textiles, and nonferrous metals. In addition, exports of finished products which could help to offset these deficiencies, are also in a rapidly deteriorating position. Furthermore, we are faced with the same question whether the concern is with the depletion of the world-wide reserves or the deficiency of indigenous resources in the U.S. Today we require a greater supply of materials than at any previous time in our history. Our national overall annual requirements for materials are expected to continue to grow by several percent each year through the end of the century. Figure 7.1 illustrates current supply change and use patterns for several major materials, and Table 7.1 summarizes the U.S. per capita consumption. The U.S. already depends on foreign supplies for the majority of its tungsten, chromium, manganese, platinum, mica, bauxite, cobalt, nickel, asbestos, and about a dozen other mineral commodities. In addition, current engineering applications of zinc, nickel, copper, cobalt, lead, tin, and the precious metals are cutting into the world’s proven reserves.

That technological innovation can assist industry to keep pace with growing demand for materials by offsetting some of the above constraints is illustrated by the case of copper. At the turn of the century, typical ore grades from copper mines were about 5% copper. Yet today, the average grade of copper deposits mined in the U.S. is less than one percent copper—about 14 pounds per ton. Although the available copper has decreased drastically in grade, improvements in mineral and metallurgical practices still allow production of copper at a reasonable price. Indeed, there is potential