6

Youth Values, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Influencers

Youth analysts are increasingly speaking of a new phase in the life course between adolescence and adulthood, an elongated phase of semiautonomy, variously called “postadolescence,” “youth,” or “emerging adulthood” (Arnett, 2000). During this time, young people are relatively free from adult responsibilities and able to explore diverse career and life options. There is evidence that “emerging adults” in their 20s feel neither like adults nor like adolescents; instead, they consider themselves in some ways like each. At the same time, given the wide variety of perceived and actual options available to them, the transition to adulthood has become increasingly “destructured” and “individualized” (Shanahan, 2000). Youth may begin to make commitments to work and to significant others, but these are more tentative than they will be later. Jobs are more likely to be part-time than at older ages, particularly while higher education, a priority for a growing number of youth, is pursued. There is increasing employment among young people in jobs limited by contract, denoted as contingent or temporary. Such jobs are often obtained through temporary job service agencies. Young people are also increasingly cohabiting prior to marriage or as an alternative to marriage.

This extended period of youth or postadolescence is filled with experimentation, suggesting that linking career preparation to military service might be attractive to a wider age range of youth than among traditionally targeted 17–18-year-olds who are just leaving high school (especially extending to youth in their early and mid-20s). But what about their values of citizenship and patriotism? Are young Americans motivated to serve? Are their parents and counselors supportive? Is there a

link between volunteering in the community and a desire to serve in the military?

This chapter is divided into two sections: the first deals with youth values and the second focuses on the individuals and events that influence or reinforce youth values. Our analysis of youth values includes (1) whether and how values have changed over time, (2) what trends can be anticipated in the future, and (3) changes in youth views of the military. Some primary questions regarding trends in youth values are

-

What are the important life goals for young people?

-

How do youth think about and act on values related to citizenship, civic participation, and patriotism?

-

What are their educational goals beyond high school?

-

What are considered the most important or desirable characteristics of a job?

-

How do youth feel about work settings?

-

What do youth believe about military policy and missions and about the military as a place to work?

The data we draw on to address these questions come from three large national survey databases supplemented by a locally based longitudinal study, several cross-sectional studies, and small observational studies as available.1 The three national databases are

-

Monitoring the Future, a nationwide study of youth attitudes and behaviors covering drug use plus a wide range of other subjects, conducted annually by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan (Bachman et al., 2001b; Johnston et al., 2001; see also <http://www.monitoringthefuture.org>). In-school questionnaire surveys of high school seniors have been conducted each year since 1975; similar surveys of 8th and 10th grade students have been conducted since 1991. The survey sample sizes range from approximately 14,000 to 19,000. The study includes follow-up surveys of smaller subsamples of graduates from all classes from 1976 onward.

-

Youth Attitude Tracking Study, a nationwide survey of youth attitudes about various aspects of military service, their propensity to enlist, and the role of those who influence youth attitudes and behavior, conducted by the Department of Defense from 1975 through 1999. In the

-

latest survey, approximately 10,000 telephone interviews were conducted. The age range of participants was 16–24.

-

The Alfred P. Sloan Study, a nationwide longitudinal study of students conducted by the National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago, from 1992 to 1997. The goal was to gain a holistic picture of adolescents’ experiences with the social environments of their schools, families, and peer groups. The methodology included survey, telephone interviews, experience sampling, sociometric reports, and supplemental interviews with those who might influence youth (Schneider and Stevenson, 1999). The sampling was designed to ensure diversity, not to provide population representativeness. Students were drawn from grades 6, 8, 10, and 12. The total sample was 1,211 students.

The locally based study is the Youth Development Study, conducted at the Life Course Center, University of Minnesota (Mortimer and Finch, 1996). The main purpose of this study is to address the consequences of work experience for youth development, mental health, achievement during high school, and the transition to adulthood. One thousand 9th graders were randomly selected in 1987 from the St. Paul, Minnesota, public school district; these youth have been surveyed annually through 2000, from the ages of 14–15 to 27. Selected subsamples of the respondents have been interviewed to develop a better understanding of the subjective transition to adulthood.

The second section of the chapter reviews the scientific literature and data characterizing youth influencers, drawing on (1) the literatures of socialization, attitude formation and change, and youth development as they inform decisions about early career development and (2) information regarding the role of influencers to the extent that it informs early career decisions. The focus of our analysis is on the aspects of the career decision-making process that bear most directly on youth propensity to enlist in the military.

TRENDS IN YOUTH VALUES

Although a primary source of data for this section is the Monitoring the Future survey, we rely more particularly on a report examining these data concerning high school seniors’ and young adults’ views about work and military service (Bachman et al., 2000a). That report covers trends from 1976 through 1998. Where useful, certain findings have been updated through 2001. The dominant finding from that report was stability rather than change over time in youth views about work and about military service, although there were also important changes that are examined in the following sections. The topics presented include: (1) important

goals in life, (2) citizenship, civic participation, and volunteerism, (3) education and work, and (4) views of the military.

Important Goals in Life

What are the life goals of youth, how have they changed over time, and what are the implications for military enlistment? Table 6-1 shows percentages of high school seniors in the Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys who rated as “extremely important” each of five goals in life (these five were selected from a longer list as being potentially relevant to military service decisions). The table shows young men and women separately and compares recent graduating classes (1994–1998) with classes nearly two decades earlier (1976–1980). Among young men, the percentages shifted only modestly over two decades, and the rank ordering was unchanged. Among young women, the shifts in percentages were small also, and the rank orderings showed only one trivial change (fourth and fifth places reversed). There were, on the other hand, some consistent differences between the male and female ratings, as noted below.

Among the items listed in the table, the highest importance ratings by far were assigned to “finding purpose and meaning in my life.” Just over half of the males in each time period rated it as extremely important, and the proportions of females were even higher. This item showed little correlation with military propensity during the last quarter of the 20th century, and from this we might infer that military service during that period was not seen as superior or inferior to other pursuits as a means for finding purpose and meaning in life. But the fact that most young adults still rate this as extremely important suggests that if military service in future years can provide such opportunities—and be perceived as doing so—the appeal is likely to be strong.

“Having lots of money” grew in importance among young men and young women between the classes of 1976–1980 and the classes of 1994– 1998, as can be seen in the table. The percentage of young people in the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) surveys who, two years after high school, thought having lots of money was very important also increased from 1974 to 1994 from slightly over 10 percent to approximately 35 percent (Larson presentation, 4th Committee Meeting—Irvine, December 2000).

According to data from the MTF surveys, “making a contribution to society” was somewhat less likely than money to be rated as extremely important by young men, whereas among young women it was a bit more likely. So are today’s youth altruistic? Or materialistic? And have young people been shifting in one direction or the other? The data show only modest changes over time, and the gender differences also remain

TABLE 6-1 Importance Placed on Various Life Goals: Comparison of Rank Orders

much the same. “Finding purpose and meaning in one’s life” seems more personal and possibly more selfish than “making a contribution to society,” but it is perhaps also more realistic and less grandiose. However, data from the Sloan study show that participants considered altruism as the most important value among a host of job values (Csikszentmihalyi and Schneider, 2000:50).

Two items relating to geography were included in Table 6-1 because they were hypothesized to affect willingness to enlist in military service. It was expected that propensity and actual enlistment would be below average among those who placed high priority on living close to parents and relatives, but above average among those who considered it important to “get away from this area of the country.” These expectations were correct with respect to the latter dimension, but the findings with respect to living close to parents and relatives were more complex. Specifically, young men who entered military service had been lower on this dimension when they were high school seniors, but after enlistment the importance of this dimension increased significantly, and they no longer were

below average in the importance they attached to living close to parents. (This pattern did not appear consistently among the small numbers of military women in the samples.) In any case, the items concerning geography were at the bottom of the importance rankings for both males and females at both times. It thus appears that military service may have some extra appeal for those who want to move to a different area, but for most individuals that is not a matter of great importance.

Citizenship, Civic Participation, and Patriotism

As shown in Table 6-1, a substantial portion of youth feels that it is “extremely important” to make a contribution to society. We need to consider how this finding relates to (or manifests itself in) civic participation, volunteerism, and the propensity to enlist in the services. There are many potential determinants of Americans’ national or civic-related attitudes and behaviors and many reasonable indicators of these phenomena. As a result, it is not easy to determine whether change has occurred and, if so, what the sources of such change might be. Some observations, however, are noteworthy. Trust in government, responsiveness to proximal political events, voting in national elections, and many other forces may be pertinent. Some commentators believe that growing materialism and individualism have diminished civic society in America; they provide evidence that political participation and civic engagement in general are declining (Putnam 1995a, 1995b; Bellah et al., 1985; Easterlin and Crimmins, 1991). Survey researchers find that trust in government declined from the 1950s to the 1990s (Alwin, 1998). The attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, may have altered this picture.

At the same time, youth are described as having relatively little interest in national politics, and they have low rates of voting in national and congressional elections (Tables 6-2a and 6-2b). This has been the case since 1972, when the voting age was lowered to 18 by the 26th amendment to the Constitution. Youth’s relative disinterest in traditional formal politics appears to be a trend that extends beyond U.S. horizons (Youniss et al., 2002). Recent surveys in the United States show that adolescents have little accurate knowledge about global issues or national political processes and at least until recently have felt little sense of threat, or potential threat, to their country (Schneider, 2001). This lack of knowledge may also have been altered by the September 11 events. Furthermore, recent studies at the National Opinion Research Center suggest that middle school and high school students (grades 6, 8, 10, and 12) are the most bored and the least engaged when they are attending history classes (Schneider, 2001; Csikszentmihalyi and Schneider, 2000:152).

TABLE 6-2a Presidential Voting by Age

Those who are more politically active among today’s youth often do not champion causes or goals that could be considered national in focus; instead they tend to direct their energies toward the resolution of global problems or to issues that might be more aptly described as promoting the welfare of humanity at large. Such issues are worldwide, not national, in scope and include human rights, poverty within and between nations, discrimination in all its manifold forms, the eradication of disease, animal rights, and environmental protection.

Table 6-2b Congressional Voting

|

|

Percentage Reporting They Voted in Congressional Elections by Age, 1974–1998 |

|||||

|

Year |

18–20 |

21–24 |

25–34 |

35–44 |

45–64 |

65 and older |

|

1974 |

20.8 |

26.4 |

37.0 |

49.1 |

56.9 |

51.4 |

|

1982 |

19.8 |

28.4 |

40.4 |

52.2 |

62.2 |

59.9 |

|

1986 |

18.6 |

24.2 |

35.1 |

49.3 |

58.7 |

60.9 |

|

1990 |

18.4 |

22.0 |

33.8 |

48.4 |

55.8 |

60.3 |

|

1994 |

16.5 |

22.3 |

32.2 |

46.0 |

56.0 |

60.7 |

|

1998 |

13.5 |

N/A |

28.0 |

40.7 |

53.6 |

59.5 |

|

SOURCE: Statistical Abstract of the United States. |

||||||

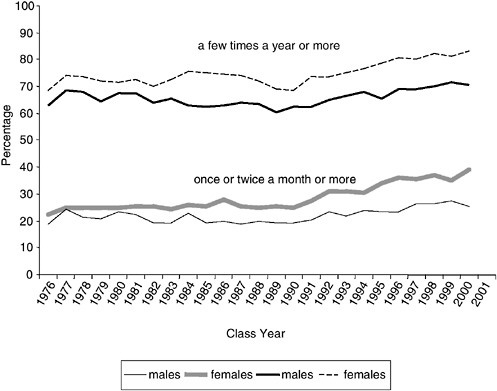

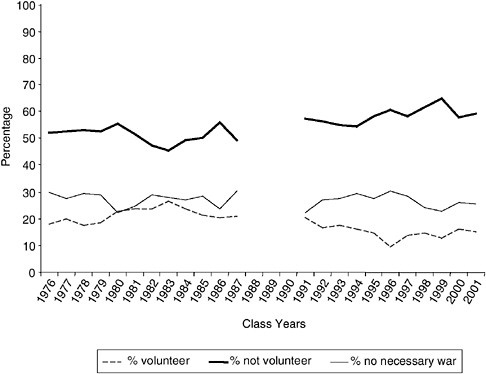

Although some evidence suggests that civic participation is declining, there also is evidence that volunteerism among youth is on the increase (Wilson, 2000). As Figure 6-1 shows, the MTF surveys provide some confirmation. From 1990 to 2000 the proportion of high school seniors who participated in community affairs or did volunteer work at least a few times a year rose gradually from about 65 to about 75 percent, and the proportion who did so at least once or twice a month also rose by about 10 percentage points—from just over 20 to more than 30 percent. Furthermore, the proportions of MTF seniors who considered it quite or extremely important to be a leader in the community increased from 21 percent in 1976 to 36 percent in 1990 and to 39 percent in 2000. These findings suggest that the avoidance of national concerns has been accompanied by an emphasis on local as well as global problems. While representing a more specific scope, local activities can be a crucial element in the development of civic engagement. Youniss and his colleagues, focus-

FIGURE 6-1 Percentage of high school seniors who participate in community affairs, class years 1976–2001, by gender and survey form number.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

ing on volunteering in the community, stress that civic activity during adolescence has lasting consequences (Youniss et al., 2002; Youniss and Yates, 1997; Youniss, McLellan, and Yates, 1997; Yates and Youniss, 1996). Their work is based on the theory that behavior drives attitude change. For example, high school volunteers in a soup kitchen, over the course of their service, developed empathy for the homeless as fellow human beings, reflected on their own advantages, and more generally began to consider broader political and moral issues as they thought about the circumstances of their own lives. In so doing, these youth had the opportunity to experience themselves as citizens, to develop a sense of efficacy as effective political agents, and to become more highly motivated to engage in their communities as adults.

Confirming evidence for the benefits of volunteerism has been found in data from the Youth Development Study. The data show that volunteer participation during high school is part of the lives of a substantial minority of Minnesota youth; 37 percent reported at least some volunteer activity while in high school (Johnson et al., 1998). Youth select themselves to volunteer on the basis of previous orientations (e.g., high educational aspirations, higher educational plans, higher grade point averages, higher academic self-esteem, and a higher intrinsic motivation toward school work). However, when the effects of previous attitudes are taken into account, participation in volunteer work was found to foster intrinsic work values, including the importance of service to society as well as enhanced anticipation of future involvement in the community as adults (Johnson et al., 1998). Volunteering also reduced the propensity toward later illegal activity as the respondents began the transition to adulthood (Uggen and Janikula, 1999). In this study, volunteering did not exert an independent effect on educational plans, academic self-esteem, or grade point average.

Furthermore, Verba et al. (1995) found that high school extracurricular activities, particularly participation in school government and clubs (but not sports), predict later political participation. Studies of social movement activists likewise support the conclusion that civic participation during adolescence and young adulthood encourages responsibility in youth, as well as more responsible and active political participation in adulthood (e.g., McAdam, 1988; Fendrich, 1993). Moreover, the effect of volunteering in high school on volunteering during the following four years has been shown to be significant, when numerous relevant background variables as well as prior altruistic and community-oriented values are taken into account (Oesterle et al., 1998; Astin, 1993). The extent to which volunteerism influences activities immediately after high school, such as postsecondary education or military service, is not known.

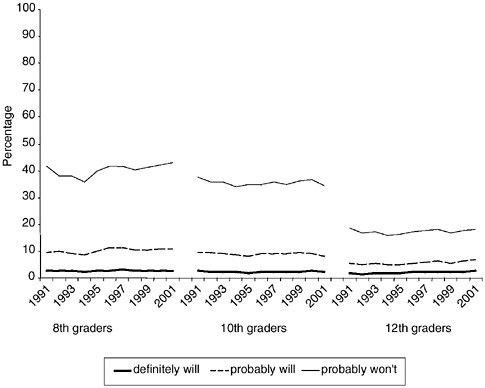

Education and Work

Educational and Occupational Aspirations

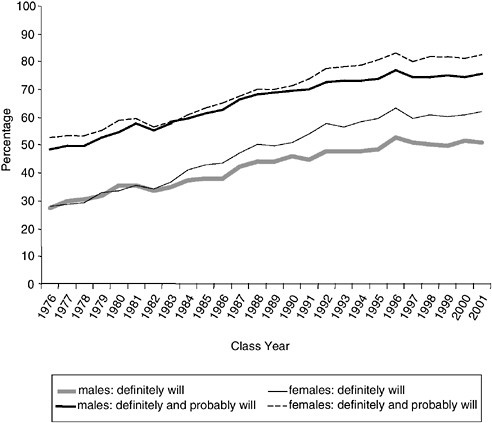

As discussed in Chapter 5, high school graduates have a number of competing opportunities open to them in the worlds of both education and work. During the last quarter of the 20th century, aspirations to complete four-year college programs rose dramatically. As Figure 6-2 shows, fewer than 30 percent of MTF high school seniors in the late 1970s expected “definitely” to complete college, but by the mid- to late 1990s about 60 percent of female seniors and about 50 percent of male seniors expected to do so. If those “probably” expecting to complete college are included, the shift is from about 50 percent in the late 1970s to about 80 percent among women and 75 percent among men in the late 1990s.

FIGURE 6-2 Trends in plans to graduate from a four-year college program: High school seniors, 1976–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

Looked at another way, it appears that during the space of about two decades the proportions of high school seniors not expecting (“probably” or “definitely”) to complete college was cut in half—from about 50 to less than 25 percent.

If military recruitment were limited to the noncollege-bound, this great reduction in the target population would be exceedingly problematic. In fact, however, in recent years the majority of high school senior males with high military propensity have also planned to complete four years of college (Bachman et al., 2001a). Nevertheless, it is also the case that average levels of military propensity are lower among the college-bound than among others, so the rise in college aspirations has added to recruiting difficulties.

It is important to note that the proportions expecting to complete college in the MTF reached a peak in 1996 and after that changed little through the latest available data (2001). It may be that in a booming economy, some high school seniors feel less certain that college is the only route to high-quality employment. This may be particularly true of high school students who already possess high levels of computer skills, for example.

Consistent with the increase in college aspirations, there has been a rise in proportions of high school students, especially young women, expecting to obtain high status jobs. For example, between 1976 and 1995 the proportions expecting to become “professionals with a doctoral degree” increased by about half among young men and more than doubled among young women, with some decline thereafter (Figure 6-3). However, young people are generally not well informed about the kinds of educational credentials or other experiences that are required in particular kinds of work. Indeed, the National Survey of Working America (Gallup Organization, 1999) shows that 69 percent of young people ages 18–25 would “try to get more information about jobs or career options than [they] did the first time.” Yet adolescents tend to avoid courses or other experiences that could be construed as specific occupational preparation. Apparently, such courses are seen as a diversion from a college degree program and not commensurate with the goal of obtaining high-quality employment. Furthermore, vocational and technical schools and technical certification programs are neither popular nor esteemed (Kerckhoff, 2002).

Youth may realize that the occupational world that they will enter after finishing their education may be quite different than the one that exists while they are in high school (Mortimer et al., 2002). At the same time, the importance of computer literacy in general is widely recognized (Anderson, 2002; Hellenga, 2002). However, instead of regarding technical courses in computer programming or any other technical programs as

FIGURE 6-3 Trends in expectation for kind of job at age 30 among high school seniors, by gender, 1976–2001 (percentage “professional with doctoral degree”).

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

vocational insurance, there is a tendency to take an all or nothing approach. Thus, the vast majority of youth plan to obtain a baccalaureate degree and do, in fact, enroll in colleges and universities after high school graduation.

These circumstances present challenges, as well as opportunities, for military recruitment. On one hand, the single-minded focus on getting into college and the lack of attention to the kinds of activities or experiences that would constitute useful preparation for high-quality careers lessen teenagers’ serious consideration of opportunities for technical training and related work experience in the military. On the other hand, college dropouts may be more receptive than high school students to these incentives. The decision to leave college may have been prompted by little success in the academic context or by mounting financial pressures. Older youth have had more time to pursue the extended postadolescent moratorium and may have become more attuned to the need for longer-term career planning and preparation. It is noteworthy that among 18–25-

year-old respondents to Gallup’s National Survey of Working America (June 2000), 80 percent thought they needed “more training or education to maintain or increase [their] earning power during the next few years.”

Preferred Job Characteristics

What do youth see as the most desirable characteristics of a job, and have these values changed over time? The most general observation, based on MTF surveys (Table 6-3), is that job characteristics rated as very important by high school graduates for any job they might hold were quite similar for the classes of 1994–1998 and 1976–1980 (indeed, product-moment correlations between the two sets of mean ratings were 0.97 for males and 0.96 for females). Another general observation is that the ratings for males were similar in most respects to those for females; notably, both genders gave highest importance ratings to a job “which is interesting to do” and lowest ratings to jobs with “an easy pace” and jobs “where most problems are quite difficult and challenging.” In other words, it appears that young people prefer interesting jobs that are neither too hard nor too easy.

Participants in the 1999 Youth Attitude Tracking Study (YATS) also gave high marks to “interesting job”—82 percent of the men and 85 percent of the women thought that this feature of work was extremely or very important (figures for the MTF respondents for a job “which is interesting to do” were highly comparable: aggregating data for 1994 to 1998, they were 82 percent for men and 87 percent for women).2

The Youth Development Study (YDS), conducted in the city of St. Paul, Minnesota, shows that three years after the 9th grade, when most youth were seniors (N = 930), teenagers of both genders placed high value on work that uses their skills and abilities (among males, 36 percent considered this feature “very important” and 44 percent considered it “extremely important”; comparable figures for females were 32 and 53

TABLE 6-3 Preferences Regarding Job Characteristics: Comparison of Rank Orders

|

Rank |

% Very Important |

Males 1976–1980 |

Males 1994–1998 |

Males Change |

|

How important is having a job |

||||

|

1 |

Which is interesting to do? |

86.1 |

82.1 |

–3.95* |

|

2 |

How important is being able to find steady work?a |

67.0 |

70.5 |

3.47* |

|

3 |

Which uses your skills and abilities—lets you do the things you can do best? |

68.0 |

66.3 |

–1.67 |

|

4 |

Where the chances for advancement and promotion are good? |

64.4 |

64.9 |

0.44 |

|

5 |

Where you do not have to pretend to be a type of person that you are not? |

64.0 |

64.2 |

0.15 |

|

6 |

Which provides you with a chance to earn a good deal of money? |

58.1 |

62.7 |

4.60* |

|

7 |

That offers a reasonably predictable, secure future? |

63.9 |

61.2 |

–2.65* |

|

8 |

Where the skills you learn will not go out of date? |

55.5 |

50.7 |

–4.82* |

|

9 |

Which leaves a lot of time for other things in your life? |

45.8 |

48.8 |

3.00* |

|

10 |

Where you can see the results of what you do? |

56.6 |

48.6 |

–8.00* |

|

11 |

That most people look up to and respect? |

34.3 |

41.5 |

7.19* |

|

12 |

Where you can learn new things, learn new skills? |

44.1 |

41.3 |

–2.76* |

|

13 |

Where you have the chance to be creative? |

34.6 |

40.1 |

5.57* |

|

14 |

That gives you a chance to make friends? |

48.2 |

39.8 |

–8.47* |

|

15 |

Which allows you to establish roots in a community and not have to move from place to place? |

40.9 |

38.7 |

–2.24 |

|

16 |

Where you get a chance to participate in decision making? |

30.3 |

35.4 |

5.15* |

|

17 |

Where you have more than two weeks’ vacation? |

23.7 |

34.4 |

10.71* |

|

18 |

That is worthwhile to society? |

37.8 |

34.1 |

–3.70* |

|

19 |

Which leaves you mostly free of supervision by others? |

31.3 |

33.8 |

2.55* |

|

20 |

That gives you an opportunity to be directly helpful to others? |

37.0 |

33.7 |

–3.27* |

|

21 |

That has high status and prestige? |

24.7 |

30.5 |

5.85* |

|

22 |

That permits contact with a lot of people? |

26.3 |

26.9 |

0.61 |

|

23 |

With an easy pace that lets you work slowly? |

11.5 |

16.5 |

4.96* |

|

24 |

Where most problems are quite difficult and challenging? |

14.8 |

13.8 |

–0.95 |

|

Rank |

% Very Important |

Females 1976–1980 |

Females 1994–1998 |

Females Change |

|

How important is having a job |

||||

|

1 |

Which is interesting to do? |

91.2 |

86.9 |

–4.25* |

|

2 |

Where you do not have to pretend to be a type of person that you are not? |

81.9 |

77.4 |

–4.48* |

|

3 |

How important is being able to find steady work?a |

61.3 |

76.4 |

15.12* |

|

4 |

Which uses your skills and abilities—lets you do the things you can do best? |

75.4 |

74.1 |

–1.37 |

|

5 |

That offers a reasonably predictable, secure future? |

62.7 |

66.6 |

3.88* |

|

6 |

Where the chances for advancement and promotion are good? |

60.3 |

61.6 |

1.27 |

|

7 |

That gives you an opportunity to be directly helpful to others? |

60.9 |

56.9 |

–4.05* |

|

8 |

Where the skills you learn will not go out of date? |

52.6 |

53.5 |

0.95 |

|

9 |

Where you can see the results of what you do? |

62.7 |

53.2 |

–9.52* |

|

10 |

Which provides you with a chance to earn a good deal of money? |

45.9 |

51.8 |

5.81* |

|

11 |

That is worthwhile to society? |

50.2 |

48.6 |

–1.60 |

|

12 |

That gives you a chance to make friends? |

60.9 |

46.8 |

–14.05* |

|

13 |

That most people look up to and respect? |

38.0 |

46.6 |

8.56* |

|

14 |

Where you can learn new things, learn new skills? |

51.9 |

44.9 |

–6.98* |

|

15 |

Which allows you to establish roots in a community and not have to move from place to place? |

39.2 |

41.2 |

2.06 |

|

16 |

Where you have the chance to be creative? |

39.9 |

40.1 |

0.19 |

|

17 |

Which leaves a lot of time for other things in your life? |

35.6 |

39.2 |

3.55* |

|

18 |

That permits contact with a lot of people? |

41.3 |

38.3 |

–3.06* |

|

19 |

Where you get a chance to participate in decision making? |

26.4 |

37.2 |

10.77* |

|

20 |

That has high status and prestige? |

22.4 |

28.0 |

5.56* |

|

21 |

Which leaves you mostly free of supervision by others? |

22.3 |

26.3 |

4.01* |

|

22 |

Where you have more than two weeks’ vacation? |

12.6 |

21.8 |

9.18* |

|

23 |

With an easy pace that lets you work slowly? |

8.5 |

12.6 |

4.08* |

|

24 |

Where most problems are quite difficult and challenging? |

11.4 |

11.4 |

0.01 |

|

a% extremely important *Rankings were assigned based on respondent ratings from the class years 1994 to 1998. Significance tests were calculated using t tests with pooled variance estimates based on percentages and adjusted for design effects, p < 0.05. SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys. |

||||

percent, respectively. These youth were much less interested in work that could involve a lot of responsibility. (These jobs might be analogous to the jobs the MTF respondents also considered relatively unattractive, jobs “where most problems are quite difficult and challenging.”) Like the MTF seniors, YDS youth of the same age expressed the least interest in jobs that were “easy” (only 16 percent of the total sample attached high importance to easy work).

Against the backdrop of overall stability in work values during the last quarter of the 20th century, as demonstrated by the MTF, there are some changes and other distinctions that may be relevant to military recruiting. Several job characteristics increased in importance, and we note a few of these next.

“Having more than two weeks’ vacation” rose from 24 percent of males in 1976–1980 rating it very important to 34 percent of males in 1994–1998; among females the increase was from 13 to 22 percent. Interestingly, although military service vacation allowances are far above the standard two weeks a year associated with most jobs in the civilian sector, this item was not correlated with enlistment propensity; among those who actually did enter military service, the vacation item remained somewhat important, whereas for others it declined in importance. Perhaps because vacations of more than two weeks are one of the perquisites of military service, those serving come to value that as part of their benefits package. (In general, work values tend to change in directions that make them more congruent with the rewards that are available—Mortimer and Lorence, 1979; Mortimer et al., 1986; Johnson, 2001.) In any case, the rising importance of vacation time among high school seniors has some implications for military recruiting efforts: specifically, advertising may need to stress the vacation benefits of military service.

MTF data show that proportions rating a chance to participate in decision making as very important in a job rose from 30 to 35 percent among males and more sharply from 26 to 37 percent among females. Even higher portions of YATS respondents considered decision making important in 1999:67 percent of men and 62 percent of women. (Differences in endorsement could be linked to variation in question wording: YATS refers to “role in decision-making”; MTF says “Where you get a chance to participate in decision-making.”) However, the ranking of this item is quite close in the two surveys: 14th and 16th for men and women, respectively, in the YATS, and 16th and 19th for men and women in the MTF. Both lists contained 24 items.

Ratings of high status and prestige as very important also rose from 25 to 31 percent of males, and from 22 to 28 percent of females. These changes took place during the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s; there was no further increase (actually, a slight decline) during the 1990s. In the

MTF, having a job that most people look up to and respect was rated as important by increasing proportions of males and females; once again, this increase took place prior to the 1990s. However, this indicator of job status was ranked 11th and 13th of 24 items by males and females, respectively. In the YDS, a “job that people regard highly” was considered relatively unimportant, receiving a ranking of 11 out of 12 criteria.

Having a chance to earn a good deal of money assumed considerable importance by youth responding to the MTF surveys, and the level of importance rose over time among both males and females; here again, the increase occurred throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, with a slight decline thereafter. In addition, higher portions of YATS respondents considered pay to be extremely or very important compared with MTF participants: 90 percent of men (versus 63 percent of male MTF respondents); and 88 percent of women (versus 52 percent of female MTF respondents). However, the particular wording of the YATS item (“job with good pay”), given its less specific and more modest referent compared to the MTF item (“which provides you with a chance to earn a good deal of money”), could have generated the higher level of endorsement.

In 1999, a large portion of YATS men and women (87 and 91 percent, respectively) considered “job security” important. A comparable item in the MTF “How important is being able to find steady work” also yielded relatively high endorsement in 1994–1998 (70.5 percent of men and 76.4 percent of women). In the YDS, a steady job, good chances to get ahead, and good pay were the highest-rated job features (of 12 criteria). Thus, in all three surveys—MTF, YATS, and YDS—extrinsic rewards of work— that is, those that are obtained as a consequence of having a job rather than from the work itself—rank high in importance.

As Table 6-3 shows, several factors declined in importance among both male and female high school MTF seniors, most notably having a job that provides a chance to make friends and having a job “where you can see the results of what you do.”

Some of the other factors did not change much but show important gender differences. Jobs providing opportunities to be helpful to others, jobs that are worthwhile to society, and jobs that permit contact with a lot of people are rated as very important by higher percentages of women than men. Women YDS participants also considered opportunities to work with people rather than things and the opportunities to be useful to society more important than did men. Finally, according to MTF data, fewer women than men consider it very important to avoid supervision by others—a dimension that correlates negatively with military propensity. However, these values were not as important for either gender as the extrinsic cluster (steady work, getting ahead, good pay) or the use of skills and ability.

Preferred Work Settings

Table 6-4, taken from the MTF surveys, shows preferences for different work settings among male and female high school seniors, comparing recent classes (1994–1998) with earlier ones (1976–1980). Self-employment was the top choice among males and was high in the ratings of females also. Working for a large corporation was the second most popular setting among both young men and young women; its popularity grew during the late 1970s and early 1980s, with little change thereafter. Schools and universities also gained in popularity, particularly during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Other work settings showed relatively little overall change.

Military service consistently received the lowest ratings among both males and females (although among males social service agencies were about equally unpopular as places to work). Not surprisingly, individuals who considered military service to be a desirable workplace were above average in military propensity and actual enlistment.

Views About the Importance of Work

High school seniors’ views about the importance of work in their lives have been mostly stable, although a few modest changes are worth noting. Overwhelming majorities of MTF respondents agree or mostly agree that work will be a central part of their lives. “Being successful in work” was rated most important (of five worthy objectives) among NCES respondents two years following high school in 1974, 1984, and 1994, with some increase being demonstrated over time (to approximately 90 percent at the last year). It is especially noteworthy how much more important success in general in the work sphere is rated by NCES survey participants, as opposed to the extrinsic indicators of such success (e.g., “having lots of money,” less than 40 percent in 1994).

However, in the MTF, the proportions considering work as a central part of life declined from about 85 percent for the classes of 1976–1985 to about 75 percent for recent classes (1996–1998). During the same period there was a roughly 10 percent increase in proportions of seniors who viewed work as “only a way to make a living.” Also, after the 1970s the proportion of young men who said they would choose not to work if they had enough money to live comfortably rose from about 20 percent to about 30 percent in the late 1990s, whereas among women it remained steady at about 20 percent. Finally, as noted earlier, there has been a modest but steady increase in the proportions of high school seniors who consider it very important to have more than two weeks of vacation per year.

TABLE 6-4 Desirability of Different Working Arrangements and Settings: Comparison of Rank Orders

|

Rank |

% Desirable and Acceptable Combined |

Males 1976–1980 |

Males 1994–1998 |

Males Change |

|

Apart from the particular kind of work you want to do |

|

|||

|

1 |

How would you rate working on your own (self-employed) as a setting to work in? |

80.8 |

77.7 |

–3.17* |

|

2 |

How would you rate a large corporation as a place to work? |

64.6 |

74.2 |

9.54* |

|

3 |

How would you rate a small business as a place to work? |

69.8 |

72.3 |

2.56* |

|

4 |

How would you rate a small group of partners as a setting to work in? |

63.2 |

64.8 |

1.66 |

|

5 |

How would you rate a government agency as a place to work? |

46.1 |

52.9 |

6.85* |

|

6 |

How would you rate a school or university as a place to work? |

34.7 |

45.5 |

10.78* |

|

7 |

How would you rate a police department or police agency as a place to work? |

35.8 |

41.0 |

5.22* |

|

8 |

How would you rate a social service agency as a place to work? |

28.4 |

28.6 |

0.13 |

|

9 |

How would you rate the military service as a place to work? |

27.8 |

28.1 |

0.23 |

|

Rank |

% Desirable and Acceptable Combined |

Females 1976–1980 |

Females 1994–1998 |

Females Change |

|

Apart from the particular kind of work you want to do |

|

|||

|

1 |

How would you rate a small business as a place to work? |

73.7 |

74.6 |

0.88 |

|

2 |

How would you rate a large corporation as a place to work? |

62.0 |

74.3 |

12.31* |

|

3 |

How would you rate working on your own (self-employed) as a setting to work in? |

64.4 |

69.8 |

5.40* |

|

4 |

How would you rate a small group of partners as a setting to work in? |

58.7 |

67.5 |

8.75* |

|

5 |

How would you rate a school or university as a place to work? |

51.7 |

60.9 |

9.21* |

|

6 |

How would you rate a social service agency as a place to work? |

64.7 |

59.9 |

–4.72* |

|

7 |

How would you rate a government agency as a place to work? |

49.7 |

49.4 |

–0.36 |

|

8 |

How would you rate a police department or police agency as a place to work? |

41.3 |

39.6 |

–1.66 |

|

9 |

How would you rate the military service as a place to work? |

23.2 |

21.9 |

–1.27 |

|

*Rankings were assigned based on respondent ratings from the class years 1994 to 1998. Significance tests were calculated using t tests with pooled variance estimates based on percentages and adjusted for design effects, p < 0.05. SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys. |

||||

It must be stressed again that the changes noted here in the MTF study were modest and gradual, not at all abrupt. Furthermore, in the NCES study, the aggregate results show that “being successful in work” also became steadily more important. It is abundantly clear that aspirations and ambitions with respect to educational and occupational attainment actually rose substantially among youth during most of the last quarter-century. These shifts in aspirations have had, and will continue to have, important implications for military recruiting efforts.

Trends in Youth Views About the Military

The findings in this section are based mainly on MTF samples of high school students and young adults (Bachman et al., 2000a, 2000b; Segal et al., 1999). We begin by noting recent trends in military propensity among youth, then we turn to their views about the military service as a workplace, and finally we consider their views about the military and its mission more generally.

Trends and Subgroup Differences in Military Propensity

As Chapter 7 and 8 show, military propensity (i.e., planning or expecting to serve in the armed forces) is correlated with actual enlistment, and these correlations can be quite strong (particularly when propensity is measured near the end of high school). Following the introduction of the All-Volunteer Force in the early 1970s, there has been considerable research focused on propensity among American youth. Here, we illustrate the trends only briefly (see Segal et al., 1999, for further details, discussion, and citation of relevant other research).

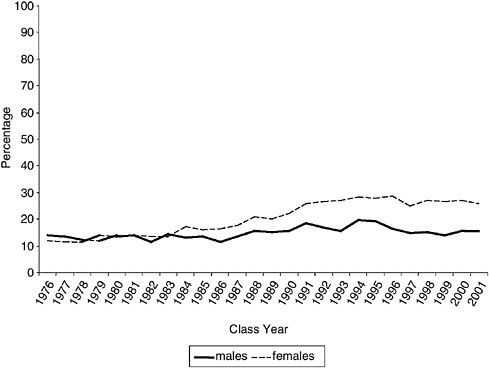

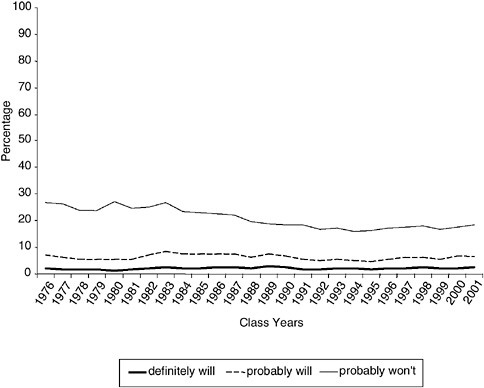

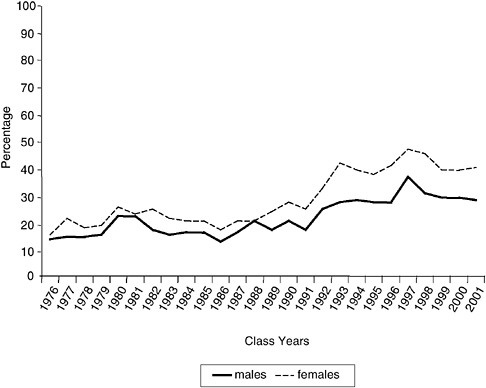

Figure 6-4 shows the trends in high school seniors’ propensity to join the military; the plots are cumulative and the spaces between the plots show the proportions in each propensity category. Specifically, the proportions of male high school seniors expecting “definitely” to serve in the armed forces varied somewhat from year to year during the last quarter of the 20th century, averaging about 10 percent throughout that period, but they have been slightly lower in recent years. Roughly equal or slightly higher proportions of young men expected “probably” to serve. However, follow-up data indicate most of them did not actually serve, whereas most of the “definitely” group did (Bachman et al., 1998). The largest percentage shift among young men was an increase in the proportion who expected that they “definitely” would not serve—from fewer than 40 percent in 1983 to more than 60 percent in 1996. This reflects primarily a shift from the “probably won’t serve” category to the “definitely won’t serve” category.

FIGURE 6-4 Trends in high school seniors’ propensity to enter the military: Males, 1976–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

NOTE: The spaces between the lines show the percentages in each of the three propensity categories.

One could conjecture that this increased certainty about not serving was simply the result of the growing proportions of young men planning on college. Although that may seem a plausible hypothesis, it is not supported by the data. For example, when the classes of 1976–1983 were compared with the classes of 1992–1998, proportions of male seniors indicating “definitely won’t” serve rose from 43 to 60 percent, whereas among the subsamples of male seniors not expecting to complete college (a category that shrank from nearly half of seniors in 1976–1983 to just over one-quarter in 1992–1998) the corresponding shift in “definitely won’t” was just about as large—from 37 to 53 percent. So it appears that the shift toward increasing certainty about not serving, shown in Figure 6-4, reflects a fairly pervasive phenomenon: the pool of young men who have not ruled out military service by the end of their senior year of high school

has been shrinking—among noncollege-bound as well as college-bound youth.

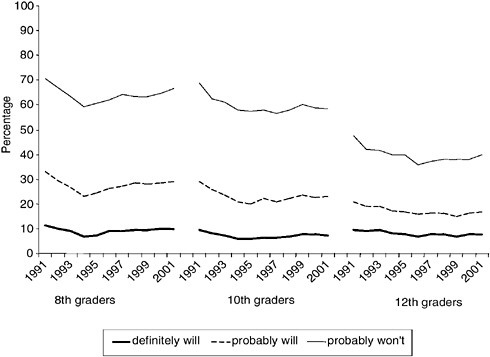

Figure 6-5 shows a similar but much smaller narrowing in proportions of female seniors who did not rule out military service. More important, the figure shows consistently very low proportions of young women expecting “probably” or “definitely” to serve; moreover, follow-up data show that even among those women “definitely” expecting to serve, most did not (Bachman et al., 1998). It is perhaps worth noting that when asked whether they would want to serve “supposing you could do just what you’d like and nothing stood in your way,” the proportion of female seniors indicating such a preference for serving was consistently higher than the combined proportions “probably” or “definitely” expecting to serve; among males the reverse was the case (Segal et al., 1999).

FIGURE 6-5 Trends in high school seniors’ propensity to enter the military: Females, 1976–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

NOTE: The spaces between the lines show the percentages in each of the three propensity categories.

FIGURE 6-6 Comparison of trends in propensity to enlist: 8th, 10th, and 12th grade males, 1991–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

NOTE: The spaces between the lines show the percentages in each of the three propensity categories.

Figures 6-6 and 6-7 make use of MTF data available from 8th and 10th grade students, beginning in 1991, and show how those in lower grades compare with 12th graders. Among males, the 8th and 10th grade data echo the above-mentioned rise in proportions expecting they “definitely won’t” serve. More important, these figures show how propensity tends to firm up as students near the end of high school. The findings for 8th and 10th graders differ little from each other, whereas by 12th grade the proportions expecting they “definitely won’t” serve are sharply higher, the “probably won’t” serve proportions are lower, and there are fewer in the “probably will” category. Among males it appears that at least a few individuals who at lower grades indicated that they “probably will” serve became more “definite” about not serving by the time they reached the end of 12th grade. There is less evidence of that among females.

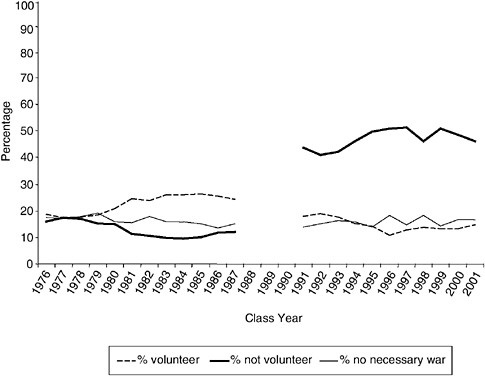

Arguably, prior to September 11, 2001, World War II was the last large-scale U.S. military effort that was overwhelmingly viewed, by both young people and the population in general, as being “necessary.” None of the U.S. military activities during the last quarter of the 20th century

FIGURE 6-7 Comparison of trends in propensity to enlist: 8th, 10th, and 12th grade females, 1991–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

NOTE: The spaces between the lines show the percentages in each of the three propensity categories.

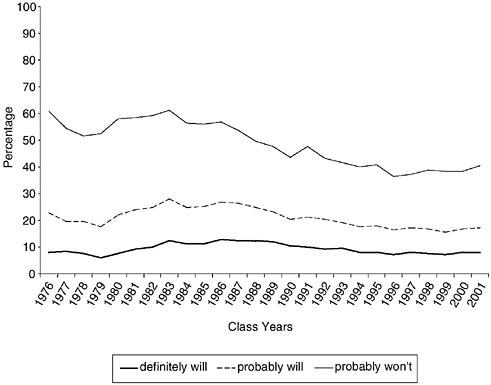

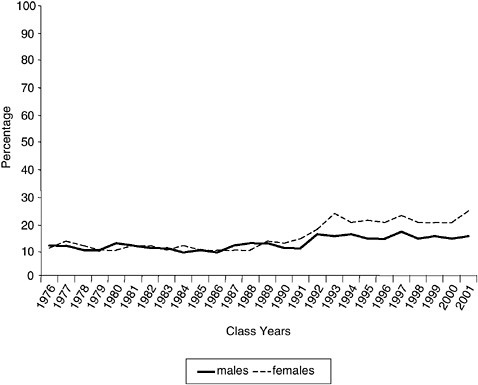

involved that level of support for shared sacrifice. One question included in most of the annual MTF surveys attempts to capture high school seniors’ willingness to serve in a “necessary” war. Specifically, the question asks: “If YOU felt that it was necessary for the U.S. to fight in some future war, how likely is it that you would volunteer for military service in that war?” The question is highly hypothetical and thus must be approached with a good deal of caution. Nevertheless, it is of interest to note that the proportions of young men and women who say they would probably or definitely volunteer under such conditions have been far higher than the proportions probably or definitely expecting to enlist under existing conditions. Figures 6-8 and 6-9 show that during the 1980s half or more of male seniors said they would volunteer for such a “necessary” war, whereas during recent years just over one-third said so; among female

FIGURE 6-8 Trends in high school seniors’ willingness to volunteer to fight in a “necessary” war: Males, 1976–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

seniors a similar, albeit smaller, decline was evident. The item includes the response option, “In my opinion, there is no such thing as a ‘necessary’ war,” and about 20 percent or fewer of males and 30 percent or fewer of females chose that option. Probably the most important trend shown by this item is that, among male seniors during the 1980s, substantially more thought they would volunteer than thought they would not— whereas in recent years that pattern was reversed. It is not clear whether this reflects a decline in patriotism, shifting perceptions of how many individuals would be needed in a modern “necessary” war, or some combination of these and perhaps other factors.

Trends in Perceptions of Military Service as a Workplace

Several survey items focusing on aspects of the military work role have shown relatively little in the way of consistent change during the last quarter of the 20th century. There were, however, consistent gender differences, with higher proportions of female than male high school se-

FIGURE 6-9 Trends in high school seniors’ willingness to volunteer to fight in a “necessary” war: Females, 1976–2001.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

niors giving high marks to military job opportunities. Thus, about 60 percent of young women, compared with about 50 percent of young men, viewed military service (to “a great extent” or “a very great extent”) as “providing a chance to advance to a more responsible position.” Roughly similar proportions viewed military service as “providing a chance for more education,” although these ratings declined very slightly over the years. Just under half of the women and about 40 percent of the men perceived military service as providing a chance for personally fulfilling work, whereas lower proportions viewed service as providing “a chance to get ahead” or “a chance to get your ideas heard.” Fewer than one in five seniors, male or female, viewed military service as a good place for a person to “get things changed and set right if...being treated unjustly by a superior.”

Two perceptions of military service as a workplace changed in a negative direction in recent years. Figure 6-10 shows a sharp rise in proportions of seniors perceiving that the armed services discriminate to a

FIGURE 6-10 Trends in perceptions that the military discriminates against women in the armed forces among high school seniors, by gender, 1976–2001. Percentage “to a very great extent” and “to a great extent” combined.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

“great” or “very great” extent against women. Figure 6-11 shows a similar rise in the (generally smaller) proportions of seniors who perceive “great” or “very great” discrimination against blacks in the armed forces. It comes as no surprise that high-propensity seniors generally saw the military workplace in a more favorable light than other seniors. But it does not appear that high-propensity seniors simply view military service through rose-colored glasses; even among the highest-propensity individuals, the perceptions of discrimination against women and against blacks rose in recent years (Bachman et al., 2000a).

Trends and Patterns in Views About the U.S. Military and Its Mission

The preceding section explored views about the military service as a place to work, and surely such views are important in understanding the

FIGURE 6-11 Trends in perceptions that the military discriminates against blacks in the armed forces among high school seniors, by gender, 1976–2001. Percentage “to a very great extent” and “to a great extent” combined.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

propensity to enlist in the armed forces. But other broader views about the U.S. armed forces and their mission may also be relevant to propensity and enlistment and are thus worth considering here. We take advantage of recently completed analyses of MTF data that compared views of high school seniors with their views in a follow-up survey one or two years later, distinguishing between young men who had entered military service, those full-time in college, and those full-time in civilian employment (the numbers of women in the samples who entered military service were too small to permit reliable estimates, so this analysis was limited to males; see Bachman et al., 2000b, for details).

Figure 6-12 shows, for young men in the high school classes of 1976– 1985 and separately for those in the classes of 1986–1995, their senior year and post-high school views about eight aspects of the U.S. military, its mission, and its role in society. All of the attitude dimensions shown in

FIGURE 6-12 Young men’s military attitudes, high school classes of 1976–1985 and 1986–1995, by post-high school occupational groups.

SOURCE: Data from Monitoring the Future surveys.

NOTE: A score of 5 = highly promilitary, 3 = neutral, and 1 = not promilitary.

the figure are based on 5-point scales with a neutral midpoint (scored 3) and with the most “promilitary” response scored highest (5) and the least “promilitary” scored lowest (1).

Before reviewing the dimensions separately, we offer a few general observations. First, those who entered military service were consistently more promilitary than those who did not; however, in most respects, these differences were not especially large. Second, the differences were evident before the end of high school, with generally little further change

after actual enlistment (although two important exceptions are noted below). Third, the comparisons across the two decades (classes of 1976–1985 versus classes of 1986–1995) showed a high degree of replication in subgroup differences, and across most dimensions there were only modest overall changes. We now look at each of the dimensions in the figure, with commentary condensed from the earlier report (Bachman et al., 2000b:568–575).

Views About Military Influence and Spending. The first two dimensions shown in Figure 6-12 have to do with military influence and tell fairly similar stories (although they come from different subsamples of the MTF surveys and thus are independent replications). They show that young men in both decades generally considered military influence to be “about right” and that it ought to remain the “same as now.” Among seniors about to enter the armed forces, a slightly higher than average proportion indicated a preference for more military influence; after graduation the differences between subgroups changed only very slightly. The question about adequacy of military spending showed roughly similar differences among high school seniors; however, after enlistment those in the armed forces showed distinct increases in the proportion who viewed current military spending as “too little.” Overall preferences for military spending declined from one decade to the next, except among enlistees from the classes of 1986–1995, who enlisted during a period when military salaries rose less than inflation; these respondents showed sharp increases (averaging about three-quarters of a standard deviation) in their preferences for greater military spending.

Views About U.S. Military Supremacy. Overall, young men during the past two decades favored U.S. military supremacy and showed very little enthusiasm for gradual unilateral disarmament, as shown by the fourth and fifth dimensions in Figure 6-12. Again, on average seniors headed for military service showed the most strongly promilitary views; they were significantly higher than the college-bound in support for supremacy and significantly higher than those headed for civilian employment in their rejection of unilateral disarmament. All of the military-civilian differences grew a bit larger after high school, so here again there is some evidence of initial differences (self-selection) that were then enlarged after entrance into different post-high school environments (socialization).

Views About Possible Military Intervention. Young men over the past two decades have been fairly supportive of the proposition that “the U.S. should be willing to go to war to protect its own economic interests”; large proportions of young men in all three subgroups agreed, and few

disagreed, with that statement. Support for military intervention was lower when the purpose was to protect “the rights of other countries” rather than U.S. economic interests. Changes between senior year and follow-up (one or two years later) were small and not significant for all groups, indicating no socialization effects attributable to post-high school environments; however, modest selection effects were evident.

Views About Unquestioning Obedience. “Servicemen should obey orders without question: Agree, Disagree, or Neither.” The final entry in Figure 6-12 shows responses to this item. This deceptively simple question is actually a bit like a trick question on a test. A correct answer would be “Yes, servicemen should obey orders provided the orders are lawful.” Such a response was not offered to respondents. In recent decades, high school seniors split their answers nearly evenly between agreement and disagreement, with many choosing the “neither” midpoint (coded 3). As can be seen in the figure, among young men, the agree responses slightly outnumber the disagree ones (among young women, data not shown, the split is even closer, although there is slightly more disagreement than agreement).

The data in Figure 6-12 show modest selection effects; high school seniors headed for military service were significantly more likely than their classmates to endorse unquestioning obedience. But upon actual entry into military, some of the enlistees changed their views, and most such changes were in the direction of lessened support for unquestioning obedience. It thus appears that military socialization largely cancelled the initial differences. The authors of the study commented on this finding as follows (Bachman et al., 2000b:574–575):

Arguably, the changes found with respect to obedience should meet with the approval of the military—and civilian—leadership, because such socialization has the effect of “correcting” some initial misconceptions about whether obedience in the armed forces should be absolute. Military doctrine maintains that service personnel are responsible to obey only lawful orders and to judge whether orders are lawful before following them. Clearly, such guidelines are quite different from the concept of “unquestioning obedience”; therefore, the changes found among servicemen in response to the obedience item suggest socialization consistent with military doctrine and training.

YOUTH INFLUENCERS

Young people’s beliefs, values, and attitudes are learned. They are formed and can be changed in interaction with others. It is therefore useful to inquire about who those influential others might be. In this

section the focus shifts from content to agency, from what beliefs, values, and attitudes influence youth propensity to enlist to who influences their propensity and how youth incorporate those influences into their career plans and decisions. While there are many potential influences on the propensity to enlist, the strongest are from a person’s social environment, particularly family and friends (Strickland, 2000).

The purpose of this review is not to summarize cumulative theory and research on youth development but, more modestly, to identify those nexuses in the career decision-making process that bear most directly on propensity to enlist in the military. We limit our examination of the literature in three ways. First, we define influencers narrowly, i.e., in interpersonal terms. We do not consider impersonal influences, including TV, film, radio, the Internet, print outlets, or associated media. Second, we maintain a close focus on the dependent variable, propensity to enlist in the military. We draw on the literatures of socialization, attitude formation and change, and youth development only to the extent that it informs early career decision making. We recognize that there are youth exposed to lawless influences that result in them being disqualified from military service (Garbarino et al., 1997), but examination of the causes of deviant behaviors are beyond the scope of this study. Third, we limit inquiry to variables that can be manipulated, by which we mean variables admissible to intervention in military recruitment policy and practice.

Background

The primary domains in which youth function are families, schools, neighborhoods or communities, and, to a lesser extent, the workplace. Briefly stated, people influence one another in three basic ways. A person can exert influence on another through the provision of reward and punishment, through teaching or explicit guidance, or by modeling what is perceived as appropriated or desirable behavior. We accept these processes as given.

Over the past 40 years, theory and research on youth influencers has evolved from efforts to understand youth attitudes and behaviors in terms of largely undifferentiated reference groups to more fine-grained significant-other influences. Taking Coleman’s seminal work, The Adolescent Society (1961), as a point of departure, the youth cohort was described as a society unto itself, a “world apart” that differs radically from adult society. Coleman’s adolescent society was a counterculture, even a contra-culture. His youth were rebellious, at odds with their parents and the rest of adult society. He memorably characterized the relationship between adult and youth cultures as a “generation gap,” a caricature that domi-

nated popular conceptions of the nation’s youth through the remainder of the century.

Challenges to the generation gap thesis surfaced in both the popular and technical literature over the decades that followed. For example, in the mid-1970s DeFleur (1978) reported that male and female Air Force cadets experiencing periods of career indecision turned more to their parents (45 percent) and other adults (48 percent) than to siblings (2 percent) or peers (5 percent) for career advice. When asked who had the most influence on their futures, jobs, and careers, the cadets identified their fathers as the biggest influence and their mothers as second in importance.

Soon thereafter, Stanford University issued a news release reporting that 4 out of 5 Stanford juniors sought advice on career planning from their parents, and 9 out of 10 sought parental advice on personal problems (Stanford University News Service, 1980). Rutter (1980) published an extensive meta-analysis of research on parent-child relationships in the United Kingdom and the United States, concluding that “young people share their parents’ values on the major issues of life and turn to their parents on most major concerns.” Taking dead aim at the generation gap thesis, Rutter asserted that “the concept that parent-child alienation is a usual feature of adolescence is a myth.”

MTF findings from 1976 through 1998 consistently show that a bit fewer than half of high school seniors thought their ideas agreed with their parents’ ideas when it comes to how the students spent their money and their leisure time, whereas just over half perceived agreement about what is okay to do on a date. About two-thirds reported that their ideas about what they should wear were mostly or very similar to their parents’ ideas. Although roughly two-thirds reported having a fight or argument with parents three or more times during the past year, about two-thirds also indicated that overall they were more satisfied than dissatisfied with how they got along with their parents. Agreement was stronger on more fundamental issues. About three-quarters thought their ideas and their parents’ ideas were very similar or mostly similar with respect to religion, politics, what values are important in life, and what they, the students, should do with their lives. Finally, views about the value of education showed high and growing agreement with parents between 1976 and the early 1990s; the proportions perceiving mostly or very different views declined from 14 to about 8 percent, whereas proportions perceiving very similar views rose from about 50 to about 65 percent. Notably, this increase in perceived close agreement about the value of education coincided with the increase in proportions of high school seniors reporting that they definitely expected to complete a four-year college program.

Empirical evidence to the contrary, the generation gap definition of parent-youth relations persisted, which may have had the positive effect of intensifying inquiry into generational differences and parent-child relations in both the popular and technical literatures. For example, a Reader’s Digest study of four generations (Ladd, 1995) reported that Americans in every age group share basic values, concluding that the finding “explodes the generation-gap myth—for good.” A Sylvan Learning Centers study (International Communications Research, 1998) asked identical questions of teenagers and their parents about perceived and actual career aspirations and reported remarkable similarities in parent-child responses across a variety of issues.

The persistence of the generation gap definition of parent-youth relations illustrates a noteworthy feature of much literature that characterizes youth. There is a penchant not limited to the popular press to dramatize, sensationalize, and otherwise mythologize youth behaviors and attitudes—to the detriment of youth (Youniss and Ruth, 2002). Adelson illustrated the point some years ago in an article in Psychology Today in which he cited the 1972 national election as an example. There had been talk that Democrat George McGovern would get the youth vote. After all, young people were supposed to be doves. Young people were supposed to be liberals. And young people would turn out to vote. The popular notion was that the youth vote would carry the election for McGovern. At the same time, youth studies were reporting that young people were as divided in their views on Vietnam as were their elders; that young people were probably more hawkish on war issues than were their elders; and that young people were less likely to vote, not more likely to vote, than were their elders. What happened? McGovern lost, convincingly. The conventional wisdom was wrong.

Against this backdrop, it is instructive to examine what is known about youth influencers and how they affect youth career decision making in terms of accumulated theory and empirical research.

The Achievement Process

The social psychological model of the achievement process provides a useful initial framework within which to identify major influencers and key processes that affect youth career decisions. In The American Occupational Structure, Blau and Duncan (1967) documented the fact that sons’ educational and occupational achievements depend largely on their parents’ educational and occupational achievement levels. To be sure, Blau and Duncan were interested in such issues as how much mobility occurred in occupational careers and how sons’ career outcomes compared to their fathers—issues of intra- and intergenerational mobility and strati-

fication. They were not interested in youth influencers and career decision-making processes per se. They asked: What are the ways that family education and occupation advantages or disadvantages transfer from one generation to the next? How is it that family levels of achievement remain relatively stable across generations? Why is there an intergenerational correlation (typically r = 0.3) between fathers’ and sons’ levels of occupational prestige?

Their research and that of others bear directly on the question of who influences youth career decisions. Following Sorokin and Parsons, Blau and Duncan reasoned and provided empirical confirmation for the theses that level of education is the key means by which society selects and distributes youth into occupational roles, and that education serves the critical socialization function of instilling achievement values and orientations in youth. Sewell and colleagues (Sewell et al., 1969, 1970) criticized the Blau and Duncan model for being too structural and too simplistic, as well as for its failure to explain the interpersonal processes that influence youth career decisions. Building on earlier work by Haller and Miller (1971), Sewell and colleagues (Sewell et al., 1969, 1970; Sewell and Hauser, 1975) expanded the model into a social psychological explanation of who influences youth aspirations and achievements and how that process works over time.

Simply stated, the model indicates that parental levels of education, occupational prestige, and income predispose youth in career directions in three ways that sequentially involve a young person’s academic ability and performance, the expectations others have for her or him, and the youth’s own career aspirations. What a young person aspires to is the critical link in the process. Formed and modified in interaction with other people, young people assess their own educational and occupational prospects in terms of their understanding of their abilities and past performance. Independently, influential others also evaluate the young person’s potential and communicate their career expectations to her or him. Because individuals and families live in social networks with similar levels of education, occupational prestige and income, those with influence in a young person’s life—including teachers and peers—tend to have levels of education, occupational prestige, and income similar to the youth’s parents and therefore provide career encouragement, role models, and expectations that complement parental values. Thus formed, career aspirations set a young person on a career trajectory. A young person’s self-reflection (Haller and Portes, 1973) is complemented by the independent evaluations of significant others (Woelfel and Haller, 1971) who communicate their expectations to the young person thus influencing his or her career aspirations, which is the strongest predictor of eventual career achievements.

Sewell and Hauser documented the predictive and explanatory power of the social psychological model of the achievement process at length (1972). Alexander et al. (1975) offered strong independent support based on a national sample. Otto and Haller (1975) provided conceptual replications based on four datasets and, assessing the convergence of theory and research across datasets, concluded that there is strong support for the social psychological explanation of the achievement process (see also Featherman, 1981; Hotchkiss and Borrow, 1996).

Significant-Other Influences

Significant others are people who are important and influential in the lives of others. The social sciences distinguish two kinds of significant others, role-incumbent and person-specific significant others. Role-incumbent significant others have influence because they have power and authority over a young person, who, for that reason, is beholden to them. Examples include parents, teachers, and police officers. Person-specific significant others, by comparison, are chosen by the individual. Examples include best friend, role model, and confidant—relationships based on understanding and trust.

Person-specific significant others have influence not because they have power associated with their role, but because individuals choose to follow them as models and exemplars. Young people follow them not because they have to, but because they want to, which positions person-specific significant others to make a difference in young people’s lives.

The empirical literature on the development of aspirations and achievements sketches the achievement process with broad-brushed strokes, and that literature is largely limited to estimating the effects of parents, teachers, and peers on respondents’ aspirations and achievements. That literature concludes that parents have the critical influence (Sewell and Hauser, 1975) on sons’ career aspirations and achievements. However, the large-scale longitudinal datasets on which achievement research tends to be based do not lend themselves to sharply focused inquiry into youth influencers. It is therefore instructive to intensify inquiry into youth career influencers in two ways: by broadening the inquiry to include more potential influencers and by shifting the focus from selected role-incumbent significant others to person-specific significant others.

Two studies inquired directly of youth about who influenced their occupational choice. Rather than assuming that persons in particular roles influenced youth and then measuring that influence, both studies asked the youth to specify who influenced specific aspects of their career plans.

In the Youth Development Study (Mortimer, 2001) students were surveyed about their experiences in the family, school, peer group, and work-

place each year during high school (1988–1991). Following a question about occupational choice, Mortimer and colleagues asked the high school seniors: “Have any of the following people influenced your choice of this kind of work?” Respondents were instructed to circle all that apply from a list of 15 possibilities.

Several observations follow from the results. Two-thirds of seniors identified a friend as the person who influenced their choice of occupation “very much, much, or somewhat.” Mothers followed closely. An adult working in the same field was chosen third most often, followed by father and teacher or coach at school. Fewer than half of the seniors identified anyone else as having influenced their choice of work—e.g., siblings, aunts and uncles, grandparents, another relative, a guidance counselor, a work-study coordinator, a neighbor or adult friend, or a priest, minister, or rabbi. It is noteworthy how prominently person-specific significant others were identified as influencers—particularly friends and adults working in the same field. Very few youth mention no influencers on their career choices. Clearly, young people seek and find guidance from others in their vocational decision making.

There were no differences in the number of influencers identified by adolescent gender, race, or nativity, but youth from two-parent families reported more influencers than those from other family structures. Their advantage comes from having two parents to draw on for help in thinking through their vocational goals. Other YDS data indicate that sons were particularly influenced by their fathers’ s occupational values. The transmission of values from parents to children was mediated by close, communicative family relationships (Ryu and Mortimer, 1996).