7

Determinants of Intention or Propensity

The preceding chapters have demonstrated that demographic and economic variables have not been able to account for all of the important variation in recruiting. In particular, after accounting for changes in the economy, recruiting resources, and demographic factors, there remains an unexplained negative trend in enlistments throughout the 1990s. Similarly, considerations of traditional attitudes and values have also provided little insight into variations in recruitment.

At the same time, however, one variable has consistently been shown to be a very good predictor of recruitment—the propensity to enlist. For example, as reported earlier, Bachman et al. (1998) found that among male high school seniors in class years 1984–1991, enlistment within the next six years was strongly related to propensity (R = 0.50, Eta = 0.55, p < 0.001). Moreover, while 70 percent of those male seniors strongly inclined join the military within six years, only 30 percent of those moderately inclined, and only 6 percent of those who said they “definitely will not join” actually did so.1 Similarly, Wilson and Lehnus (1999), using data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Survey (YATS), also found a strong association between propensity and enlistment. Although no correlation was reported, these investigators concluded that “positively propensed high school seniors are applying to enter the military about five times as

frequently as those who indicated negative propensity. Propensity is an imperfect but very significant predictor of enlistment behavior.”

Given that propensity, as it is measured in both the YATS and Monitoring the Future (MTF), is extremely similar to the psychosocial construct of intention, and that intention has played a central role in many behavioral theories,2 in this chapter we use behavioral theory to help explain why some young adults are, and some are not, inclined to join the military. More specifically, we briefly review some behavioral theories and describe an integrated model of behavioral prediction. We then consider the application of this model to the prediction of propensity (for both males and females) and enlistment, presenting available data. Finally we point out the implications of the model for military recruitment.

THEORIES OF BEHAVIOR

There are many theories of behavioral prediction, such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1985, 1991; Ajzen and Madden, 1986), the theory of subjective culture and interpersonal relations (Triandis, 1972), the transtheoretical model of behavior change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983, 1986, 1992; Prochaska et al., 1992, 1994), the information/motivation/behavioral-skills model (Fisher and Fisher, 1992), the health belief model (Becker, 1974, 1988; Rosenstock, 1974; Rosenstock et al., 1994), social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977, 1986, 1991, 1994), and the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein et al., 1991). However, there is a growing academic consensus that only a limited number of variables need to be considered in predicting and understanding any given behavior (Fishbein, 2000; Fishbein et al., 2001). Three theories have most strongly influenced intervention research, outlined below.

Social Cognitive Theory: According to social cognitive theory, there are two factors that serve as primary determinants underlying the initiation and persistence of any behavior. First, the person must have self-efficacy with respect to the behavior. That is, the person must believe that he or she has the capability to perform the behavior in the face of various circumstances or barriers that make it difficult to do so. Second, he or she must have some incentive to perform the behavior. More specifically, the expected positive outcomes of performing the behavior must outweigh the expected negative outcomes.

Social cognitive theory has focused on three types of expected outcomes: physical outcomes (e.g., performing the behavior will make me healthy); social outcomes (e.g., performing the behavior will please my

parents); and self-standards (e.g., performing the behavior will make me feel proud). Note that the expected outcomes of performing one behavior (e.g., enlisting in the Army) may be very different from those associated with performing another behavior (e.g., enlisting in the Marines). That is, one might believe that enlisting in the Army will lead to very different costs and benefits than those that will follow from enlisting in the Marines.

The Theory of Reasoned Action: According to the theory of reasoned action, performance or nonperformance of a given behavior is primarily determined by the strength of one’s intention to perform or not perform that behavior; intention is defined as the subjective likelihood that one will perform or try to perform the behavior. The intention to perform a given behavior is, in turn, viewed as a function of two basic factors: one’s attitude toward performing the behavior and one’s subjective norm concerning the behavior, that is, the perception that one’s important others think that one should or should not perform the behavior in question.

The theory of reasoned action also considers the determinants of attitudes and subjective norms. Attitudes are a function of beliefs that performing the behavior will lead to certain outcomes and the evaluation of those outcomes (i.e., the evaluation aspects of those beliefs). Subjective norms are viewed as a function of normative beliefs and motivations to comply with what the referent wants to do. Generally speaking, the more one believes that performing the behavior will lead to positive outcomes or will prevent negative outcomes, the more favorable will be one’s attitude toward performing the behavior. Similarly, the more one believes that specific individuals or groups think that one should perform the behavior and the more one is motivated to comply with those referents, the stronger will be the perceived pressure (i.e., the subjective norm) to perform that behavior.

The Health Belief Model: Although developed to help explain health-related behaviors, the health belief model can be adapted to a wide range of behaviors. According to this model, the likelihood that someone will adopt or continue to engage in a given behavior is primarily a function of two factors. First, the person must feel personally threatened by some perceived outcome, such as poor job prospects in the civilian labor market. That is, he or she must feel personally susceptible to or at risk for a condition that is perceived to have serious negative consequences. For example, in difficult economic circumstances, one might perceive a high likelihood of being unemployed and unable to support one’s family. Second, the person must believe that, in addition to preventing or alleviating this threat, the benefits of taking a particular action outweigh the perceived barriers to or costs of taking that action.

On the basis of these three theories, one can identify four factors that may influence an individual’s intentions and behaviors:

-

The individual’s attitude toward performing the behavior, which is based on his or her beliefs that performing the behavior will lead to various positive and negative consequences;

-

Perceived norms, which include the perception that those with whom the individual interacts most closely support his or her attempt to change and that others in the community are also changing;

-

Self-efficacy, which involves the individual’s perception that he or she can perform the behavior under a variety of difficult or challenging circumstances; and

-

The individual’s perception that he or she is personally threatened by or is susceptible to some negative outcome.

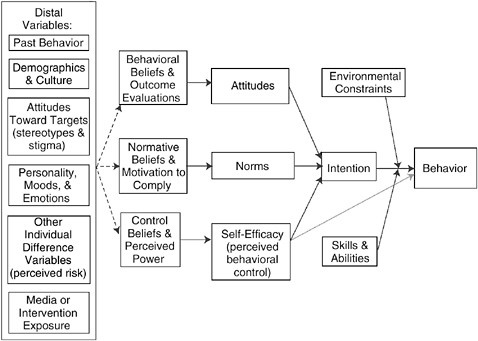

While there is considerable empirical evidence to support the role of attitude perceived norms, and self-efficacy as determinants of intention and behavior (Holden, 1991; Kraus, 1995; Sheppard et al., 1988; Strecher et al., 1986; van den Putte, 1991), this is not always the case for perceived susceptibility (or perceived risk—see Gerrard et al., 1996; Fishbein et al., 1996). Indeed, as we discuss below, it appears that perceived risk may best be viewed as having an indirect effect on intention. On the basis of these and other considerations, Fishbein (2000) has recently proposed an integrative model of behavioral prediction (see Figure 7-1).

An Integrated Theoretical Model

Looking at Figure 7-1, it can be seen that any given behavior, such as enlisting in the military, is most likely to occur if one has a strong intention to perform that behavior, if one has the necessary skills and abilities (i.e., meets military enlistment standards), and if there are no environmental constraints preventing behavioral performance. Indeed, with a strong commitment, the necessary skills and abilities, and no environmental constraints, the probability is very high that the behavior will be performed (Fishbein, 2000; Fishbein et al., 2001).

One immediate implication of this model is that very different types of interventions will be necessary if one has formed an intention but is unable to act on it than if one has little or no intention to perform the behavior in question. In some populations or cultures, a behavior may not be performed because people have not yet formed intentions to perform it, while in others, the problem may be a lack of skills or the presence of environmental constraints. In still other populations, more than one of these factors may be relevant. Clearly, if people have formed the desired

FIGURE 7-1 Determinants of behavior.

intention but are not acting on it, a successful intervention will be directed either at skill building or at removing environmental constraints.

If strong intentions to perform the behavior in question have not been formed, the model suggests three primary determinants of intention to consider: the attitude toward performing the behavior, perceived norms concerning performance of the behavior, and one’s self-efficacy with respect to performing the behavior. It is important to recognize that the relative importance of these three psychosocial variables as determinants of intention depend on both the behavior and the population being considered. Thus, for example, one behavior may be primarily determined by attitudinal considerations, while another may be primarily influenced by feelings of self-efficacy. Similarly, a behavior that is attitudinally driven in one population or culture may be normatively driven in another. Thus, before developing interventions to change intentions, it is important to first determine the degree to which that intention is under attitudinal, normative, or self-efficacy control in the population in question. Once again, it should be clear that very different interventions are needed for attitudinally controlled behaviors than for behaviors that are under normative influence or are strongly related to feelings of self-efficacy. Clearly, one size does not fit all, and interventions that are successful at changing

a given behavior in one culture or population may be a complete failure in another.

The model in Figure 7-1 also recognizes that attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy are all themselves functions of underlying beliefs—about the outcomes of performing the behavior in question, about the normative proscriptions or behaviors of specific referents, and about specific barriers to behavioral performance. Thus, for example, as was described above, the more one believes that performing the behavior in question will lead to “good” outcomes and prevent “bad” outcomes, the more favorable should be one’s attitude toward performing the behavior. Similarly, the more one believes that specific others think one should (or should not) perform the behavior in question, and the more one is motivated to comply with those specific others, the more social pressure one will feel (or the stronger the subjective norm) with respect to performing (or not performing) the behavior. Finally, the more one perceives that one has the necessary skills and abilities to perform the behavior, even in the face of specific barriers or obstacles, the stronger will be one’s self-efficacy with respect to performing the behavior.

It is at this level that the substantive uniqueness of each behavior comes into play. For example, the barriers to and consequences of enlisting in the military may be very different from those associated with reenlisting in the military. Yet it is these specific beliefs that must be addressed in an intervention if one wishes to change intentions and behavior. And although an investigator can sit in the office and develop measures of attitudes, perceived norms, and self-efficacy, she or he cannot tell you what a given population (or a given person) believes about performing a given behavior. It is necessary to go to members of that population to identify salient outcome, normative, and efficacy beliefs. To put this somewhat differently, one must understand the behavior from the perspective of the population one is considering.

The above discussion focuses attention on a limited set of variables that have consistently been found to be among the strongest predictors of any given behavior (see, e.g., Petraitis et al., 1995). Although focusing on behavior-specific variables may provide the best prediction of any given behavior, this approach does little to explain the genesis of the beliefs that underlie attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy. Clearly, the beliefs that one holds concerning performance of a given behavior are likely to be influenced by a large number of other variables. For example, one’s life experience will influence what one believes about performing a given behavior, and thus one often finds relations between such demographic variables as gender, ethnicity, age, education, socioeconomic status, and behavioral performance. Similarly, young adults who are unemployed may have very different beliefs about joining the military from those who are em

ployed. Other factors that may influence one’s beliefs include perceived risk, moods and emotions, culture, knowledge, attitudes toward objects or institutions, types of social networks, and media exposure.

Although these are all important variables that may help us to understand why people hold a given belief, they are perhaps best seen as “distal” or background variables that exert their influence over specific behaviors by affecting the more “proximal” determinants of those behaviors. This can also be seen in Figure 7-1.

According to the model, distal or background factors may or may not influence the behavioral, normative, or self-efficacy beliefs underlying attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy. Thus for example, while men and women may hold different beliefs about performing some behaviors, they may hold very similar beliefs with respect to others. Similarly, rich and poor, old and young, those who do and do not plan to go to college, those with favorable and unfavorable attitudes toward law enforcement, and those who have or have not used drugs may hold different attitudinal, normative, or self-efficacy beliefs with respect to one behavior but may hold similar beliefs with respect to another. Thus, there is no necessary relation between these distal or background variables and any given behavior. Nevertheless, distal variables, such as cultural and personality differences and differences in a wide range of values, should be reflected in the underlying belief structure.

It is probably worth noting that when properly applied, theoretical models such as the one presented in Figure 7-1 recognize, and are sensitive to, cultural and population differences. For example, the relative importance of each of the variables in the model is expected to vary as a function of both the behavior and the population being investigated. Moreover, these types of models require one to identify the behavioral, normative and self-efficacy beliefs that are salient in a given population. Thus, these types of models should be both population- and behavior-specific.

Applying the Model

The first step in using a behavioral prediction or behavioral change model is identifying the behavior that one wishes to understand or change. And unfortunately, this is not nearly as simple or straightforward as is often assumed. First, it is important to distinguish between behaviors, behavioral categories, and goals. Research has shown that the most effective interventions are those directed at changing specific behaviors (e.g., walk for 20 minutes three times a week) rather than behavioral categories (e.g., exercise) or goals (e.g., lose weight; see Fishbein, 1995, 2000).

Note that the definition of a behavior involves several elements: the action (enlisting), the target (the Army), and the context (after graduating from high school). Clearly, a change in any one of the elements changes the behavior under consideration. Thus, for example, enlisting in the Army is a different behavior from enlisting in the Navy (a change in target). Similarly, enlisting in the Army after graduating from high school is a different behavior from enlisting in the Army after completing college (a change in context). Moreover, it is also important to include an additional element—time. For example, enlisting in the Army in the next three months is a different behavior from enlisting in the Army in the next two years. Clearly, a change in any one element in the behavioral definition will usually lead to very different beliefs about the consequences of performing that behavior, about the expectations of relevant others, and about the barriers that may impede behavioral performance.

The second step in applying a behavioral theory is to identify a specific target population. For any given behavior, both the relative importance of attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy as determinants of intention or behavior and the substantive content of the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs underlying these determinants may vary as a function of the population under consideration. Thus, it is imperative to define the population to be considered. Target populations may be defined in very different ways. Often, populations are divided into groups according to characteristics of social diversity, such as age, income, gender, and education. Even a single group characterized by one demographic variable will comprise multiple diverse audiences. For example, the population of men between ages 18 and 25 will include men varying in ethnicity, income, education, age, family history, and beliefs.

Information about intended audiences can be obtained through national or local survey data or through formative research, which involves data collection on audiences’ sociodemographic characteristics, behavioral predictors or antecedents such as audience beliefs, values, skills, attitudes, and current behaviors. There is rarely only one way to segment a diverse population. Given limited resources, it is critical to prioritize and select a particular population segment in lieu of others.

Once one or more behaviors and target populations have been identified, theory can be used to understand why some members of a target population are performing the behavior and others are not. That is, by obtaining measures of each of the “proximal” variables in the model (i.e., beliefs, attitudes, norms, self-efficacy, intentions, and behavior), one can determine whether a given behavior such as enlisting in the military is not being performed because people have not formed intentions to enlist or because they are unable to act on their intentions. Similarly, one can determine, for the population under consideration, whether intention is

influenced primarily by attitudes, norms, or self-efficacy. And finally, one can identify the specific beliefs that discriminate between those who do or do not intend to perform the behavior. These discriminating beliefs need to be addressed if one wishes to change or reinforce a given intention or behavior. When the beliefs are appropriately selected, changes in these beliefs should, in turn, influence attitudes, perceived norms, or self-efficacy—the proximal determinants of one’s intentions to engage in and often the actual performance of that behavior.

Identification of these beliefs requires understanding the behavior from the perspective of the population in question. That is, proper implementation of theory requires one to go to a sample of that population to identify the relevant outcomes, referents, and barriers (Middlestadt et al., 1996). Once this has been done, survey data can be used to identify the beliefs that discriminate between those who do or do not intend to perform the behavior in question (Hornik and Woolf, 1999).

APPLICATION OF BEHAVIORAL THEORY TO MILITARY RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

Despite the fact that propensity, as measured by most investigators, has repeatedly been found to be the best single predictor of enlistment, and despite the fact that propensity can best be viewed as a measure of intention to join the military, there have been very few attempts to use behavioral theories, such as those presented above, as a framework for predicting and understanding propensity. Although we were able to find no studies that have applied behavioral theory to the prediction of propensity to enlist or actual enlistment, we did find two studies that were concerned with predicting retention.

Predicting Retention in the British Women’s Royal Army Corps

In 1976 there were many more applicants for the British Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) than could be accepted and a set of selection procedures was adopted. Despite this, a certain number of applicants (about 16 percent) left the Corps after the first six weeks of basic training. Because this was quite expensive, the Army Personnel Establishment wanted to see if they could predict who would leave and who would stay. In an attempt to answer this question, Keenan (1976, reported in Tuck, 1976) conducted a study using the theory of reasoned action. Consistent with expectations, intentions to “stay in the WRAC after my training at Guilford” as measured in the first three days of joining the Army, were very good predictors of retention (R = 0.68, df = 98, p < 0.001).

More important, this intention was significantly related to both their attitudes toward “joining the WRAC” and their subjective norms concerning “my joining the WRAC” (multiple R = 0.59, beta weights not reported), and these two measures were in turn predicted from their underlying behavioral and normative beliefs. More specifically, their behavioral beliefs that “My joining the WRAC” would lead to 12 outcomes (identified through formative research: gives me opportunities to travel, gives me independence, means good pay, means being away from home, etc.) weighted by their evaluations of these outcomes was correlated 0.47 with their attitudes. Their normative beliefs (also identified through formative research: about mother, father, friends in the service, boyfriend, etc.) weighted by their motivation to comply with these referents correlated 0.58 with their subjective norm.

In a further analysis, Keenen found that the main factors influencing retention were the women’s beliefs that “My joining the WRAC is a chance to get a career” and that their parents would support this decision. In addition, she found that the more favorable the women were toward “making new friends,” “independence,” “discipline,” and “being away from home,” the more likely they were to stay in the WRAC.

Reenlistment in the National Guard

As part of a larger study, Hom et al. (1979) used the theory of reasoned action to predict the propensity to reenlist of Army National Guard members as well as the actual reenlistment behavior of 228 men whose current term of enlistment expired in the next six months. Because the paper was concerned with comparing various models, the researchers measured only attitude, subjective norm, intention, and behavior. Consistent with expectations, the men’s intention to “reenlist in the National Guard when my present enrollment expires” was highly correlated with their actual reenlistment (R = 0.67, p < 0.001). Also consistent with expectations, their propensity to reenlist was highly correlated with both their attitude toward “reenlisting in the National Guard at the next opportunity” (R = 0.79) and their subjective norm with respect to “reenlisting in the guard at the next opportunity” (R = 0.69). The multiple correlation was 0.81, with both attitude (beta = 0.42) and norms (beta = 0.17) contributing to the prediction.

Other than these two studies, most information concerning factors influencing measured propensity have come from two surveys: Monitoring the Future (MTF) and the Youth Attitude Tracking Survey (YATS). In MTF, high school seniors (surveyed during the spring, just prior to graduation) are asked “How likely is it that you will do each of the following things after high school? The activities listed include “serve in the armed

forces.” Respondents are asked to choose from the following alternatives: definitely won’t, probably won’t, probably will, and definitely will.

As we discussed in Chapter 6 (see Figure 6-4, this volume), there has been a modest decline in the proportion of male high school seniors who say they definitely will or probably will serve in the armed forces from the mid-1980s onward. In contrast, during the same period, there has been a steady and significant increase in the proportion who say they “definitely will not serve” and a corresponding decrease in those who say they “probably will not serve.” Figure 6-5 shows responses by female high school seniors to the same question. The percentage of females who say they definitely will or probably will serve has remained relatively constant (at about 8 percent) since 1976. However, as with their male counterparts. the percentage who say they definitely will not serve has increased, with a corresponding decrease in those who say they probably will not serve.

The YATS asks respondents “How likely is it you will be serving on active duty in the [Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force]; would you say definitely, probably, probably not, or definitely not?” Those who say “definitely” or “probably” for at least one of the four services are said to have expressed “positive propensity” for military service; those who say they will “probably not” or “definitely not” join, along with those who say they “don’t know” or decline to answer, are said to have “negative propensity.” In 1991, 34 percent of males ages 16–21 were “positively propensed.” This dropped to a low of 26 percent in 1997 and 1998 and then showed a slight increase to 29 percent in 1999. More recently, respondents have also been asked about the likelihood that they would be serving on active duty “in the military.”

Predicting Propensity to Enlist from MTF Data

One major attempt to look at the psychosocial determinants of propensity and enlistment has been done by Bachman et al. (2000b). For example, Bachman et al. (2000b) predicted propensity from eight demographic variables including: race/ethnicity; number of parents in household, parents’ average education, post/current residence (e.g., farm, city/ large metropolitan region), region, intentions to attend college, high school curriculum, and high school grades. While all except high school grades contributed significantly to the prediction of propensity, the two most important predictors were race/ethnicity and college plans. Consistent with previous data, blacks were more likely than other race or ethnic groups to intend to join while those with college plans were least likely to indicate a propensity to join the military. Generally speaking, however,

these demographic variables accounted for relatively little of the variance in propensity; R2 was only 0.086 for men and 0.070 for women.

The researchers then analyzed a wide range of attitudes, values, and behaviors that they thought might be correlated with propensity. They examined roughly 140 possible predictors. They first examined the bivariate correlation of each of these 140 variables with propensity and then, for each variable that had a significant bivariate correlation with propensity, they controlled for the previously described background variables. It is interesting to note that, of the 140 predictors considered, only 14 were significantly related to propensity for men, and only 10 were significant for women. Perhaps not surprisingly, and consistent with the integrated model, the strongest single predictor of propensity for both men and women was an item that Bachman et al. viewed as an indicator of “attitude toward the military as a workplace.” More specifically, respondents were asked, “Regardless of your specific job, would you find the military an acceptable place to work?” It seems reasonable to conclude that this variable would be highly correlated with respondents’ attitudes toward joining the military. Even after controlling for the demographic background variables, this single item was correlated 0.73 with propensity for men and 0.61 for women. Only one other variable had a correlation over 0.28, and this too was considered as an indicator of the same attitude. Rather than being a single item, this latter variable was an index the authors constructed to assess “opportunities and treatment in the military.” This index was correlated 0.38 with propensity for men and 0.16 for women.

While such findings may initially appear discouraging from a recruitment perspective, they are entirely consistent with theories of behavioral prediction and change. That is, from a behavior theory perspective, demographic and economic variables, as well as more traditional measures of attitude and values, have primarily an indirect influence on a person’s decision to perform (or not to perform) any given behavior. Indeed, although one can identify hundreds of demographic, economic, and psychosocial variables that may or may not influence any behavioral decision, as we saw above, behavioral theories suggest that there is only a limited number of variables that serve as critical determinants of any given behavior. Consistent with this, MTF data suggest that young adults’ attitudes toward the military as a workplace are highly correlated with propensity. However, MTF was not designed to explore insight into why people hold such positive or negative attitudes. In order to gain some insight into this, we now consider the YATS data.

Predicting Propensity from YATS Data

As part of YATS, respondents were asked to indicate the “importance” of 5 randomly selected job attributes from a set of 26 such as “job security,” “getting money for education,” “preparation for future career or job,” “doing something for your country,” “personal freedom,” and “a job with good pay.” In addition, they were asked to indicate whether each of these five randomly selected attributes was more likely to be found in “the military,” “a civilian job,” or “equally in both.”

According to behavioral theory, the more people that believe they can attain valued outcomes from the military rather than from a civilian job, the more favorable should be their attitude toward joining the military and the higher their propensity to join the military. Because all attributes are phrased in a positive manner, ratings of importance are highly correlated with ratings of the value (i.e., extremely good, quite good, slightly good, neither good nor bad) that respondents place on these attributes. In addition, the second set of judgments can be viewed as measures of belief that the attribute would be obtained by “joining the military.” Thus, it’s possible to compute an expectancy-value score for each attribute. According to behavioral theory, this product should be most highly correlated with propensity. In order to explore this, we conducted a secondary analysis of the data. More specifically, we regressed propensity on (a) the 26 importance ratings, (b) the 26 belief ratings, and (c) the 26 belief × importance.

Because each respondent was only asked about five randomly selected attributes, the amount of missing data makes the interpretation of these regression analyses somewhat problematic. The following should therefore be considered suggestive rather than definitive. Table 7-1 shows the results of these three regressions.

It can be seen that consistent with expectations, the expectancy-value scores provided the best prediction of propensity. Moreover, it can be seen that beliefs were more important determinants of propensity than were values.

TABLE 7-1 Prediction of Propensity from Job Attributes

|

|

R2 |

Significance |

|

Importance |

0.154 |

NS |

|

Belief |

0.270 |

p < 0.02 |

|

Belief × Importance |

0.304 |

p < 0.005 |

|

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study. |

||

In looking at the particular job attributes that predict propensity, only one importance rating was significant at less than the 0.05 level. More specifically, the more these young adults felt that “doing something for my country” was important, the stronger their propensity to join the military (p < 0.01). Because of missing data and the likelihood of multicolinearity, we also consider those attributes that approach significance (i.e., that have p-values at less than 0.20). By relaxing this standard, there are two additional values that appear to influence propensity. The more people felt that a “mental challenge” was important, the lower their propensity (p < 0.15), and the more they felt that “opportunity for adventure” was important, the higher their propensity to join the military (p < 0.15).

In contrast, several beliefs appear to influence propensity. The more they believed that the military (rather than a civilian job) would allow them to be near family (p < 0.01), give them personal freedom (p < 0.05), prepare them for future jobs (p < 0.10), provide U.S. travel (p < 0.10), teach leadership skills (p < 0.15), give them something to be proud of (p < 0.15), would be doing something for their country (p < 0.15), and provide equal opportunity for minorities (p < 0.20), the stronger was their propensity to join the military.

Finally when the expectancy-value (i.e., belief x importance) scores are considered, propensity is related to being near family (p < 0.001), personal freedom (p < 0.02), getting leadership skills (p < 0.05); getting parents approval (p < 0.05); having an interesting job (p < 0.10); job preparation (p < 0.10), doing something to be proud of (p < 0.15), working with people you respect (p < 0.15), doing something for your country (p < 0.20), U.S. travel (p < 0.20), and equal opportunity for minorities (p < 0.20).

What is perhaps most surprising about these findings is the apparent lack of relationship between propensity and attributes that have often been promoted by the military—money for education, pay, job security, and working in a high-tech environment. Since it is possible that the failure of these attributes to emerge as factors influencing propensity could be due to issues of multicolinearity, and since it is probably not appropriate to consider each job attribute as independent, the committee decided it was important to examine the extent to which these 26 attributes represent more general, underlying dimensions. Given the amount of missing data, we were unable to arrive at a meaningful factor solution using traditional factor analysis. Thus we conceptually grouped attributes and used a confirmatory factor analysis procedure in AMOS (which uses all available data and does not impute missing values; see Arbuckle, 1996) to investigate whether various sets of selected attributes could be used as indicators of a more global construct. This analysis sug-

gested that five basic dimensions provided good fits to the data for both men and women:

-

Learning Opportunities: develop self-discipline, develop leadership skills, job preparation, learn new skills.

-

Working Conditions: work autonomy, work as a team, mental challenge, interesting job, work with people you respect, near family, personal freedom.

-

External Incentives: high-tech environment, money for education, good pay, job security, parental approval, earn respect.

-

Patriotic Adventure: opportunity for adventure, physical challenge, doing something for your country, foreign travel, domestic travel, doing something to be proud of.

-

Equal Opportunity: equal employment opportunity for women, equal employment opportunity for minorities, prevent harassment.

In order to explore the relations of each of these dimensions to propensity, we again used AMOS. More specifically, for each of the five dimensions, three models predicting propensity were tested: one predicting propensity from importance judgments, one predicting propensity from beliefs, and one predicting propensity from the belief x importance product. Based on the above regression analyses, we would expect that “importance” would be a significant predictor of propensity only when attributes concerning “patriotic adventure” are considered, while beliefs and the expectancy-value products would be significant predictors in all five domains. It is important to note that the prediction of propensity from beliefs is also an expectancy-value prediction. That is, since all attributes are phrased positively and represent valued outcomes, the higher the estimated belief score, the more likely it is that one will obtain a valued outcome. Thus one would expect the estimated belief x importance product to improve prediction over and above the estimated belief score only when importance is also a significant predictor of propensity.

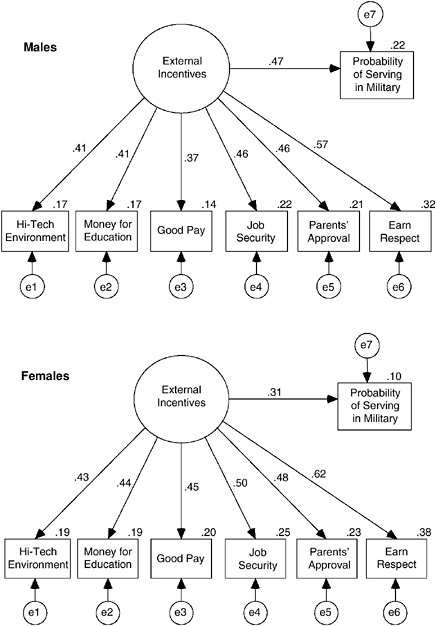

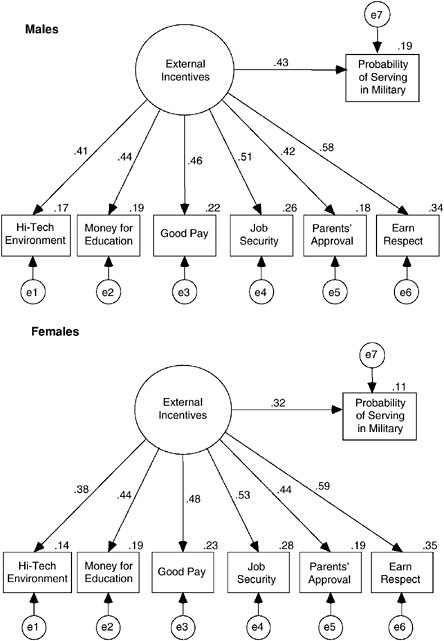

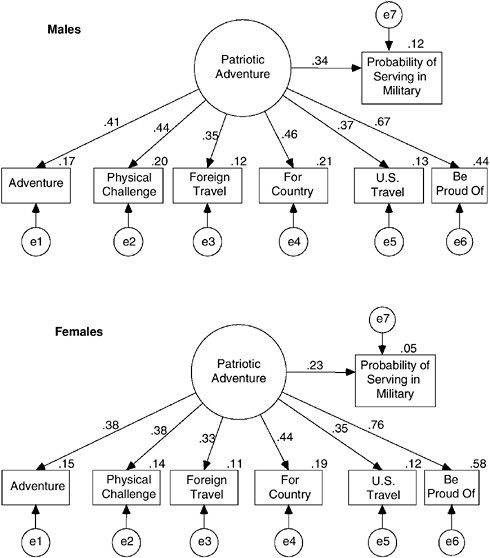

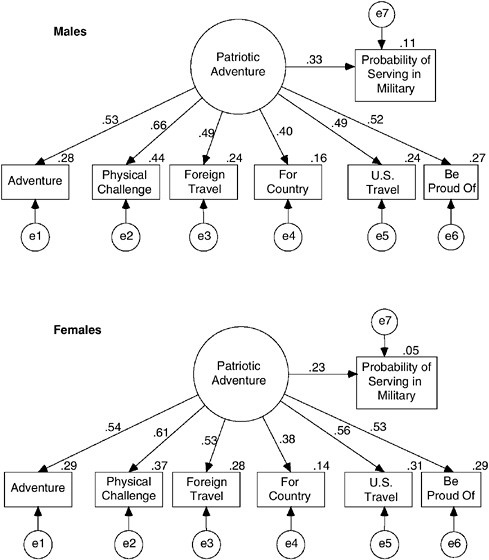

Each analysis simultaneously considered both males and females. Figure 7-2a shows how well the estimated importance of “patriotic adventure” predicted propensity; Figure 7-2b shows the relations between propensity and the estimated belief that the military (rather than civilian jobs) would lead to “patriotic adventure”; Figure 7-2c shows the role of the estimated expectancy-value score in influencing young men and women’s intentions to join the military.

Looking at Figure 7-2a, it appears that the model fits the data quite well (rmses = 0.024, TLI = 0.991) and, consistent with expectations, the estimated importance of attributes related to patriotic adventure accounts for 12 percent of the variance in young men’s propensity, and 5 percent of young women’s propensity, to enlist in the military. In Figures 7-2b

FIGURE 7-2a Predicting propensity from the importance of patriotic adventure. chi = 258.720, df = 38, p = 0.000, rmsea = 0.024, TLI = 0.991

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

and 7-2c, it appears that the model holds equally well for beliefs (rmses = 0.025, TLI = 0.990) and the expectancy-value products (rmses = 0.018, TLI = 0.993).

As expected, the more the men believed that they would be more likely to get “patriotic adventure” by joining the military (rather than by taking a civilian job), the higher their propensity to enlist (R2 = 0.11).

FIGURE 7-2b Predicting propensity from the belief that joining the military will lead to patriotic adventure. chi = 275.385, df = 38, p = 0.000, rmsea = 0.025, TLI = 0.990

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

Similarly, the more the women believed that they would be more likely to get “patriotic adventure” by joining the military, the higher their propensity to enlist (R2 = 0.05). Note, too, that taking both belief and importance into account leads to slightly better prediction than considering either one alone. That is, for men, the estimated expectancy value for patriotic adventure accounts for 21 percent of the variance in their propensity to join

FIGURE 7-2c Predicting propensity from the expectancy-value score associated with patriotic adventure. chi = 165.376, df = 38, p = 0.000, rmsea = 0.018, TLI = 0.993

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

the military and, for women, the estimated expectancy value for patriotic adventure accounts for 13 percent of the variance in their propensity to join.

These findings clearly suggest that in order to increase propensity, one should try to increase the importance of attributes such as “doing

something for my country” and “having an opportunity for adventure.” In addition, one should try to increase beliefs that these “patriotic adventure” attributes are more likely to be obtained in the military than in civilian life.

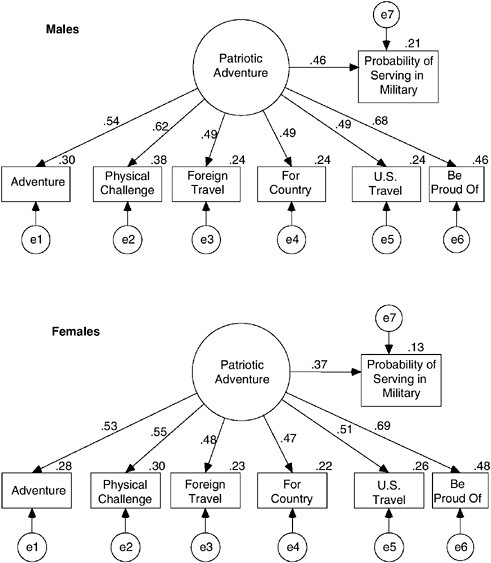

Figures 7-3a, 7-3b and 7-3c provide similar data for the role of “external incentives.” Once again it can be seen that all three models (i.e., for importance alone, for beliefs alone, and for the expectancy values) provide a good fit to the data. Here, however, it can be seen that the importance of this dimension contributes very little to the prediction of propensity (R2 = 0.02 for both men and women). In marked contrast, both beliefs and the belief x importance products are significantly related to propensity. More specifically, beliefs account for 22 percent of the variance in propensity for men and 10 percent of the variance for women’s and the belief x importance products account for 19 percent and 11 percent for men and women, respectively.

Similar analyses were done with respect to the remaining three dimensions. Table 7-2 summarizes the findings by showing the regression weights and R2 between propensity and (a) the estimated importance of each dimension, (b) the estimated beliefs that the attribute dimension would be most likely to be obtained in the military, and (c) the estimated expectancy-value score for each attribute dimension, for both men and women. There it can be seen that only the importance of “patriotic adventure” significantly contributes to propensity. In contrast, when beliefs are considered and when importance ratings are weighted by the belief that the attributes defining a given dimension are more likely to be obtained in the military than in civilian life, four of the five dimensions are found to significantly contribute to propensity. Somewhat surprisingly, these young adults appear to pay little attention to equal opportunity considerations. Note that, consistent with the earlier findings of Bachman, Freedman-Doan, and O’Malley (2000) men’s propensity is more predictable than women’s propensity. More important, considerations of external incentives and patriotic adventure are the most important determinants of propensity for both men and women.

Generally speaking, then, these analyses suggest that considerations of patriotism, adventure, external incentives, opportunities for learning, and working conditions all influence young adults’ intentions to join the military. These findings strongly suggest that, in order to increase the propensity to enlist, it will be useful to increase (a) the value young adults place on “doing something for my country” and on “opportunities for adventure,” as well as (b) their beliefs that they are more likely to be doing something for the country and that they will have a greater opportunity for adventure in the military than in civilian life. In addition, it might be useful to strengthen their beliefs that they are more likely to get

TABLE 7-2 Predicting Men and Women’s Propensity from Importance Estimates, Belief Estimates, and Expectancy-Value (Importance × Belief) Estimates

|

|

Importance |

Belief |

Importance × Belief |

|||

|

|

Beta |

R2 |

Beta |

R2 |

Beta |

R2 |

|

Men |

||||||

|

Working conditions |

0.02 |

0.00 |

0.48 |

0.23 |

0.34 |

0.11 |

|

Learning opportunities |

0.15 |

0.02 |

0.42 |

0.17 |

0.37 |

0.14 |

|

External incentives |

0.14 |

0.02 |

0.47 |

0.22 |

0.43 |

0.19 |

|

Patriotic adventure |

0.34 |

0.12 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

0.46 |

0.21 |

|

Equal opportunity |

0.03 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

0.09 |

0.01 |

|

Women |

||||||

|

Working conditions |

–0.04 |

0.00 |

0.30 |

0.09 |

0.20 |

0.04 |

|

Learning opportunities |

0.14 |

0.02 |

0.23 |

0.05 |

0.29 |

0.09 |

|

External incentives |

0.15 |

0.02 |

0.31 |

0.10 |

0.32 |

0.11 |

|

Patriotic adventure |

0.23 |

0.05 |

0.23 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

0.13 |

|

Equal opportunity |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

0.05 |

0.00 |

|

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study. |

||||||

a number of external incentives (e.g., money for education, good pay, job security, parents’ approval) from the military than from civilian life.

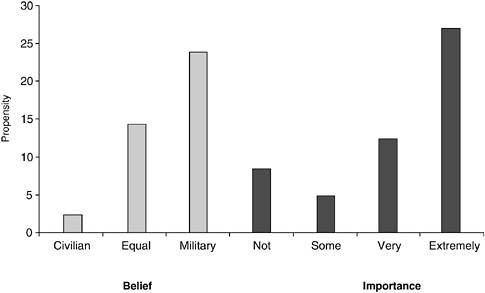

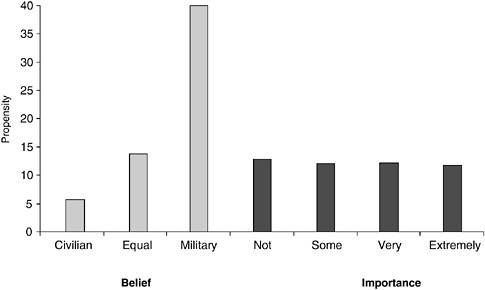

In order to illustrate this, Figure 7-4 shows how beliefs and values associated with “doing something for my country” are related to propensity. More specifically, the figure shows the percentage of young adults with positive propensity to join the military as a function of their beliefs that they are most likely to do something for the country in the military or in a civilian job (or equally in both), as well as of the degree to which they think that “doing something for the country” is important. Consistent with the above analyses, it can be seen that both importance and belief are highly related to propensity.

Looking at the three bars on the left of the figure, it can be seen that those who believe that they are more likely to be doing something for the country in the military are almost 10 times more likely to have a positive propensity to join the military (23.8 percent) than are those who believe that they are more likely to do something for the country in a civilian job (2.4 percent). Equally important, those who think that doing something for the country is “extremely” important are more than three times likely to have a positive propensity (27 percent) as are those who think that “duty to country” is “not at all important” (8.4 percent).

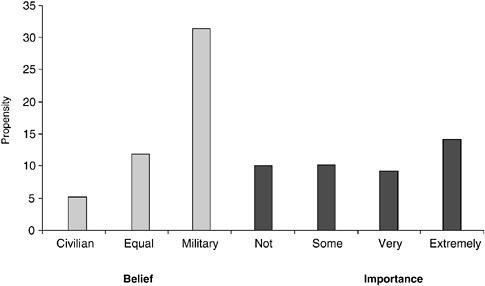

A somewhat different picture is presented in Figure 7-5. Recall that in the above analyses, we found that although the importance one placed on

FIGURE 7-4 Do something for country.

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

NOTE: Survey responses on “do something for my country.” See text for explanation.

external incentives had little to do with propensity, the more one believes that he or she is more likely to obtain these incentives in the military (compared with a civilian job), the more likely one is to have a positive propensity to join the military. Figure 7-5 considers the external incentive of “good pay.” Note that while those who believe that they are most likely to get good pay in the military are six times as likely to have a positive propensity (31.4 percent) as those who believe they are most likely to get good pay in a civilian job (5.2 percent). Those who think “good pay” is “extremely important” are only slightly more likely to have a positive propensity (14.1 percent) than are those who think that “good pay” is “not at all” important (10 percent).

One additional individual attribute is worth considering. In the previous chapter, we saw the important role that social influencers, and in particular one’s parents, play in young adults’ decisions to enter the military. Figure 7-6 shows that the more young adults believe that they are likely to gain parental approval in the military (rather than in a civilian job), the more likely they are to have a propensity to join. More specifically, 40 percent of those who believe that they are more likely to get parental approval by being in the military intend to join, while only 5.7

FIGURE 7-5 Good pay.

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

NOTE: Survey responses on “good pay.” See text for explanation.

percent of those who believe they will gain more approval in a civilian job have a propensity to join. In marked contrast, we can again see that the value these young adults place on parental approval plays little or no role in influencing their propensity to enlist.

These findings indicate that, at any given point in time, the greater the number of young people who value “patriotism” and who think that the “opportunity for adventure” is important, the greater should be the number of young people who have a positive propensity to join the military. Similarly, the greater the number of young people who believe that they are more likely to “do something for the country” or to have an “opportunity for adventure” in the military and who believe that they are more likely to obtain external incentives, such as job security, good pay, and parental approval, from the military than from a civilian job, the greater should be the pool of young adults with a propensity to join the military.

In Chapter 6, we saw that there have been relatively few changes in youth values over time. The two changes that have occurred—an increase in the value placed on educational attainment and a decrease in the value placed on doing something for the country—have undoubtedly contributed to reduced propensity and recruiting difficulties. Perhaps even more

FIGURE 7-6 Get parents’ approval.

SOURCE: Data from the Youth Attitude Tracking Study.

NOTE: Survey responses on “get parents’ approval.” See text for explanation.

problematic, however, there have been a number of substantial changes in young adults’ beliefs that valued attributes would be obtained from the military. For example, as recently as the beginning of the 1990s there was considerable agreement that one would be most likely to be doing something for the country by serving in the military. Since that time, however, there has a been a gradual erosion of this belief to the point at which more people now feel that they will be doing something for their country in a civilian job than in the military. More specifically, the net percentage attributing “doing something for the country” to the military rather than civilian jobs (i.e., the percentage attribution to the military minus the percentage attribution to civilian jobs) declined from 37 percent in 1992 to –5 percent in 1999 for men and from 39 percent in 1992 to –17 percent in 1999 for women.

Indeed, what is most startling about our analysis of the YATS data is that they clearly show a steady loss of a number of valued attributes to civilian occupations. That is, there has been a consistent erosion in the likelihood that many of these values are more likely to be obtained from the military and a corresponding increase in the likelihood that they will be obtained from a civilian job or equally in both. For example, among men, the net percentage attributing “working in a high-tech environment” to the military over civilian jobs declined from 20 percent in 1992 to –1

percent in 1999 for men and from 15 to –8 percent for women. What this means is that more young adults now believe that they will be working in a high-tech environment in a civilian job than in the military.

As another example, consider the attribute of “getting money for education.” Although the value of educational attainment has significantly increased over the past decade, the value young adults place on “getting money for education” has remained very high and has not changed over time. Once again, however, there has been an erosion in the belief that one is more likely to get money for education from the military than from civilian life and a corresponding increase in the belief that one is equally or more likely to get money for education from a civilian job.

If these trends continue, the pool of young adults with a propensity to join the military will begin to dry up. It is incumbent upon the military to develop strategies to increase the number of young adults with a propensity to join. The strategy for the past decade seems to have been to fish where the fish are (let’s go after those with a propensity and try to close the deal). At this point in time, however, it would appear that the pool needs to be restocked and enlarged. In order to do this, it will be necessary to renew a sense of patriotism and adventure and make it clear that these important values are best attained through the military. In addition, the military must continue to make young people and particularly women aware that it provides a number of extrinsic incentives, such as good pay, job security, health benefits, and vacations. Finally, the military must develop strategies to increase young adults’ beliefs that their parents (and other influencers) would approve of their going into military service. As pointed out in Chapter 6, one possible way of doing this is to direct messages toward influencers as well as to the youth per se.

The above analyses suggest that a change in advertising strategy might significantly increase the number of young adults with a positive propensity to join the military. As we discuss more fully in the next chapter, much of the military advertising to date has focused on external incentives and, except in the Marine Corps, little attention has been paid to issues of patriotism or duty to country.

At the very least, advertising should try to increase the number of young adults who have a propensity to join the military. And here it may be necessary to consider two potential audiences. On one hand, advertising could be directed at trying to move people who say they “probably will not” join the military to saying “they probably or definitely will join.” On the other hand, advertising could also be used to move people from “moderate” to “strong” propensity (i.e., from “probably will join” to “definitely will join.” If advertising were used to increase the pool of young adults with a propensity to join, it would seem quite reasonable for recruiters to concentrate their efforts on signing up those who already

have a propensity to join. However, this may often include attempts to strengthen the propensity of those with a moderate one. Issues of advertising and recruitment are addressed more fully in Chapter 8.

SUMMARY

In this chapter we have tried to show that proper application of behavioral theory can help to increase understanding of the factors influencing propensity and enlistment. However, the data necessary for a more comprehensive analysis at the individual level are currently not available. Clearly, it would be reasonable for the military to begin systematically obtaining data on the behavioral, normative, and efficacy beliefs that underlie young adults’ attitudes, perceived norms, and feelings of self-efficacy with respect to joining the military. If data of this type are obtained, it is important to recognize that all of the salient beliefs about joining the military should be considered. For whatever reason, most research to date has focused only on beliefs concerning the benefits (or positive attributes) of joining the military. There is, however, one very important potential negative consequence of joining the military: one could be injured or killed. To fully understand propensity it will be necessary to consider all of a person’s beliefs about joining the military. Clearly, if fear of death or injury is a critical determinant of propensity, then very different strategies and messages will be necessary to increase it. The committee could find few data to address this question.