5

Trends in Employment and Educational Opportunities for Youth

As they approach the completion of primary and secondary school ing, eligible youth confront the choice of entering military service. Competing with this choice are two primary alternatives: (1) entering the civilian labor market and (2) continuing education by entering college.1 In this chapter, we examine these choices, focusing on understanding the aspects of the choice that may affect the decisions of recruit-eligible youth (e.g., high school graduates).

THE DECISION TO ENLIST: A CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Underlying the rationale for examining these choices is a simple model of occupational choice: individuals compare pecuniary and nonpecuniary benefits of enlisting and conditions of service relative to their next best alternative and choose the one that provides the greatest net benefits. In this model, we hypothesize that individuals, at the completion of high school, choose a time path of jobs, training, and education that maximizes their expected welfare or utility over their lifetime. Elementary labor economics suggests that the utility of a job is a function of earnings and deferred compensation, benefits, working conditions, and hours of work (or its complement, leisure.) However, the earnings the individual can command, as well as the other aspects of the job, are a function of education, training, and experience. Hence, the individual has an incentive to

invest in additional education by attending college and to seek jobs that provide training that is generally valued in the labor market because this improves future job opportunities and earnings. The path chosen by any particular individual will depend on the individual’s tastes, innate abilities, information, and resources.

This choice model emphasizes the notion of a path of activities, rather than a single choice. In making a choice (or a series of choices), the individual invests in gathering information regarding alternatives, which can be a costly process. Furthermore, the information that the individual has with regard to various career paths is imperfect. Military service may be part of a path that also includes additional schooling and eventual entrance into the civilian labor market. Alternatively, military service could include a full career of 20 or more years of service.

In the remainder of this chapter, we outline the key aspects of each of the three major alternatives—military service, additional schooling, and civilian employment—that are likely to be relevant to the individual’s choice. We examine the tangible benefits associated with an option, the other conditions associated with that choice, and possible intangible factors.

MILITARY SERVICE

The Enlistment Process

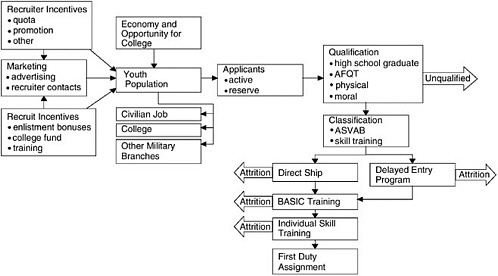

We begin by outlining the enlistment “production” process itself. Though there are differences in the details, the general process is the same for all of the Services (see Figure 5-1). All, or almost all, entrants enter at the “bottom” of a closed personnel system; there is little or no lateral entry. Consistent with our conceptual model, each Service competes for the youth population with civilian employers, colleges, and the other Services. Recruiters—the Services’ sales force—have quotas or targets for the enlistments in each period, typically one month. The Services also offer enlistment bonuses and education benefits, in addition to the basic education benefit offered to all recruits under the Montgomery GI Bill, which is targeted to qualified recruits who enlist in particular occupational specialties.

In order to qualify for military service, all applicants must first take the Armed Services Vocation Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). In addition, a background check is used to determine if the applicant is morally qualified for service. Once these two areas of qualification are met, the applicant can be offered a military job.

Most qualified applicants who accept the offer of enlistment do not begin military service immediately. Instead, they enter the delayed entry

program (DEP). While in the program, the recruit remains at home, continuing life as a civilian. The primary purpose is to schedule the recruit’s entry into service to coincide with basic and initial skill training classes and to accept applicants who are high school seniors and have not yet graduated. At some point, the recruit will enter basic training and upon completion will be assigned to a duty station. Typically, the first duty station is overseas for the Army and sea duty for the Navy.

Conditions of Military Service: An Overview

Enlistment in military service is unlike accepting a civilian job or even entering college; the military institution has a much larger influence on the member’s life while in the military. Although the service is constrained by laws and regulations and the recruit voluntarily agrees to accept the order and discipline of military life, the degree to which the military service influences the recruit’s location, hours of work, food and housing, and even leisure activities vastly exceeds that of any other choice.

The recruit begins by signing an enlistment contract that obligates the individual to serve for a specified period. This both constrains the individual’s employment over the term of the agreement and provides a degree of security in employment over the period. The potential recruit must consider this aspect of enlistment when making a decision. The contract itself is potentially enforceable, but in practice has not been strictly enforced in a peacetime, volunteer environment.2

All recruits receive basic training and most receive initial and advanced training in a particular skill. The skill training can range from technically intensive training in electronics, computers, nuclear power, or avionics to training in law enforcement, clerical skills, or mess management skills.

Initial and advanced skill training can last from a few weeks to well over a year. During this time in training, the member receives full pay. Most formal training occurs when the Service member is relatively junior and receives only modest pay. Nevertheless, civilian-sector employers do not typically provide training in such general areas as basic and advanced electronics, at no cost to the employee, while paying the employee’s full salary. One of the reasons the military Services are able to do this is that

the recruit is obligated by a potentially enforceable enlistment contract to serve for a specified period of time.

The military member is subject to military discipline and to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, meaning they must obey all lawful orders. On rare occasions, this may mean being deployed for significant periods of time without notice and the possible cancellation of individual or family plans. More typically, it means planned periods of family separation.

Frequent moves are a fact of life in the military, with planned rotations about every three years. The armed forces of the United States are stationed all over the world and on all of its oceans. The typical Service member considers some of these locations very interesting and desirable assignments, but others are not. Members are assigned to positions throughout the world through a process that might be described as “share the pain, share the gain.” Typically, this means that the member can anticipate that relatively onerous assignments will be followed by relatively desirable assignments, as judged by the typical member.

For most permanent assignments, the member may choose to bring his or her family. The Service, according to schedules of coverage and allowances, reimburses moving expenses for the member and his or her family. Moreover, there is an infrastructure at most military locations to support the member’s family. Some types of assignments, however, are designated as “unaccompanied.” The member’s family does not accompany the member to the location. These assignments are typically to onerous locations or locations of higher risk. Unaccompanied tours are typically of shorter duration.

The frequency of moves and the overseas assignments present hardships, primarily to married members or members with dependents. First, frequent moves make it difficult for the member’s spouse to pursue certain types of careers. Second, at some locations, there are very limited opportunities for any spouse employment.3 Third, members with school age children can find the frequency of moves disruptive to their education. However, the recruit typically has no dependents. The opportunity to be stationed overseas or even in other parts of the United States in the first term of service may be seen more as an opportunity for travel than a hardship.

Members in all of the military Services who are assigned to combat or combat support units—which includes most initial duty assignments for recruits—will be subject to deployments. Deployments occur when the

unit leaves its permanent station for a period of time (ranging from several days to many months) for an operational or training mission. During periods of deployment, the member is separated from his or her dependents. In the Navy, deployments typically mean time at sea. In the other Services, humanitarian, peacekeeping, and similar missions are typical deployments.4

Working conditions may be onerous or unpleasant, depending on the job, the assignment, and the member’s tastes, but they may also be quite pleasant. On sea duty, sailors work and live on a ship for 180 days at a time. Accommodations aboard ship are not to everyone’s taste, especially for junior enlisted members.

Military members may be physically at risk from two sources. First, some types of military jobs are inherently risky. Any job that puts one in constant proximity to live ordnance is potentially risky. Jobs requiring sailors to be on the deck of a carrier during launch and recovery operations, operation of high-performance aircraft, airborne operations, diving, and demolition are a few examples. Second, all members are subject to being deployed to hostile fire areas—to be put in harm’s way—regardless of their particular jobs. Some units, particularly combat and combat support units, and some types of jobs are more at risk than others.

In principle, active-duty members are “on call” 24 hours per day. Actual hours of work will vary by the nature of the job or skill, the current assignment or duty station, and factors that may be affecting the command at any particular time. It is not unusual for sailors on board ship, for example, to work 16 hours per day. Similarly, soldiers and airmen may work equally long hours in preparing for a deployment, for example. However, normal duty hours under typical circumstances will require a workweek not unlike that in the civilian sector. Unlike the civilian sector, however, members will be called on to take rotations for extra duty, such as watch standing. There is no overtime pay.

Military Compensation System

Because recruits enter voluntarily, rather than through conscription, pay and benefits must remain competitive with alternatives, if the Services are to attract and retain required numbers of qualified personnel. The military compensation system for active-duty members consists of a complex array of basic pay, nontaxable allowances, special and incentives pays, deferred compensation, and in-kind benefits. We briefly review its major elements below.

Current Cash Compensation

Basic pay is the major element of military compensation. Monthly basic pay is a function of the member’s rank or pay grade and years of service. The enlisted pay table in effect as of January 1, 2001, is shown in Table 5-1. Typically, recruits enter at the lowest pay grade, E-1. However, if they have some college or are highly qualified and are entering certain occupational specialties, they may enter at an advanced pay grade, typically E-2 or E-3.

Members progress through the pay table in two ways: length of service or promotion. As they gain longevity, pay increases in the ranges of the pay table. In addition, members may be promoted. Typically, promotions through E-3 are relatively automatic as long as the member is making satisfactory progress. From E-4 through E-9, promotions become increasingly competitive. Typically, the member must reach noncommissioned officer status (E-4) to reenlist beyond the first term of service. Members who remain competitive for promotions will reach senior noncommissioned officer (NCO) or chief petty officer status at about their 12th year of service.

In addition to basic pay, all members receive either housing and food in-kind, or a tax-free allowance for housing (basic allowance for housing or BAH) and a tax-free allowance for food (basic allowance for subsistence or BAS). These allowances vary by pay grade and, unlike the civilian sector, by dependency status. Members with dependents receive higher allowances than those without dependents. In addition, BAH varies by location, reflecting geographic variation in rental prices. BAH rates reflect the cost of renting standardized housing types across different geographic locations. Table 5-2 shows current BAH rates for enlisted members for Virginia.

BAH is substantial—about 33 percent of basic pay. Moreover, it is not subject to federal or state income tax, increasing its value by 15 percent or more for most enlisted members. Unmarried junior enlisted members (E-4 and below) typically live in on-base housing, however, and receive rations in-kind.

Regular military compensation (RMC) is defined as the sum of basic pay, BAS, and BAH (including the tax advantage on each). It is the most frequent way that military cash compensation is defined.

All members are paid from the common basic pay table, regardless of occupation. Similarly, allowances vary only by rank, dependency status, and location. Yet the training and experience offered in some military occupations is much more valuable in the civilian sector than that offered in other occupations. Hence, other things being equal, it is more difficult to retain personnel in some occupations than in others.

TABLE 5-1 Monthly Basic Pay Table for Enlisted Members (effective 1 January 2001)

|

|

Years of Service |

|||||||

|

GRADE |

<2 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

12 |

|

E-9 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$0.00 |

$3,126.90 |

$3,197.40 |

|

E-8 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2,622.00 |

2,697.90 |

2,768.40 |

|

E-7 |

1,831.20 |

1,999.20 |

2,075.10 |

2,149.80 |

2,227.20 |

2,303.10 |

2,379.00 |

2,454.90 |

|

E-6 |

1,575.00 |

1,740.30 |

1,817.40 |

1,891.80 |

1,969.50 |

2,046.00 |

2,122.80 |

2,196.90 |

|

E-5 |

1,381.80 |

1,549.20 |

1,623.90 |

1,701.00 |

1,777.80 |

1,855.80 |

1,930.50 |

2,007.90 |

|

E-4 |

1,288.80 |

1,423.80 |

1,500.60 |

1,576.20 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

|

E-3 |

1,214.70 |

1,307.10 |

1,383.60 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

|

E-2 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

|

E-1>4 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

|

E-1<4 |

964.80 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

Years of Service |

|||||||

|

GRADE |

14 |

16 |

18 |

20 |

22 |

24 |

26 |

|

|

E-9 |

|

$3,287.10 |

$3,392.40 |

$3,498.00 |

$3,601.80 |

$3,742.80 |

$3,882.60 |

$4,060.80 |

|

E-8 |

2,853.30 |

2,945.10 |

3,041.10 |

3,138.00 |

3,278.10 |

3,417.30 |

3,612.60 |

|

|

E-7 |

2,529.60 |

2,607.00 |

2,683.80 |

2,758.80 |

2,890.80 |

3,034.50 |

3,250.50 |

|

|

E-6 |

2,272.50 |

2,327.70 |

2,367.90 |

2,367.90 |

2,370.30 |

2,370.30 |

2,370.30 |

|

|

E-5 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

2,007.90 |

|

|

E-4 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

1,653.00 |

|

|

E-3 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

1,385.40 |

|

|

E-2 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

1,169.10 |

|

|

E-1>4 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

1,042.80 |

|

|

E-1<4 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

SOURCE: Available: <http://www.military.com>. NOTE: Basic pay for 0–7 and above is limited to $11,141.70, Level III of the Executive Schedule. Basic pay for 0–6 and below is limited to $9,800.10, Level V of the Executive Schedule. |

||||||||

An efficient compensation system recognizes differences in civilian opportunities through pay differentials by occupation. Although all enlisted occupational specialties are paid from a common pay table, there are two ways in which pay differentiation is achieved. First, some occupational specialties have more rapid rates of promotion than others. This means that personnel in these occupations will receive greater compensation. These tend to be occupations requiring technical skills that are highly transferable to civilian employment. Moreover, because the promotion system in the Services tends to be at least partially driven by vacant posi-

TABLE 5-2 Enlisted Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH) Rates: Virginia

|

|

GRADE |

|||||||

|

Location |

E2 |

E3 |

E4 |

E5 |

E6 |

E7 |

E8 |

E9 |

|

Without Dependents |

||||||||

|

Woodbridge |

$744 |

$744 |

$744 |

$793 |

$825 |

$874 |

$925 |

$930 |

|

Newport News |

559 |

559 |

559 |

580 |

596 |

636 |

705 |

750 |

|

Norfolk |

626 |

626 |

626 |

645 |

658 |

683 |

733 |

773 |

|

Fort Lee |

529 |

529 |

529 |

537 |

546 |

580 |

624 |

654 |

|

Richmond |

506 |

506 |

506 |

558 |

592 |

649 |

713 |

724 |

|

With Dependents |

||||||||

|

Woodbridge |

$817 |

$817 |

$858 |

$922 |

$938 |

$1,005 |

$1,078 |

$1,150 |

|

Newport News |

590 |

590 |

624 |

676 |

822 |

871 |

925 |

997 |

|

Norfolk |

654 |

654 |

675 |

707 |

837 |

901 |

972 |

1,044 |

|

Fort Lee |

541 |

541 |

569 |

613 |

669 |

709 |

763 |

853 |

|

Richmond |

583 |

583 |

631 |

705 |

742 |

768 |

797 |

877 |

|

SOURCE: Available: <http://www.military.com>. |

||||||||

tions, it serves as a natural equilibrating mechanism. Low retention increases vacancies, which make promotions more rapid, and increases pay, which increases retention.

The second source of pay differentiation is “special and incentive pays.” The purpose of these pays are to compensate for risks, onerous conditions, or responsibilities associated with particular occupational specialties or assignments and to increase retention in areas where there are, or would otherwise be, shortages. Special and incentive pays are the primary way in which pay differentials are introduced. They can be targeted to occupations and experience levels for which increased retention is needed the most. Because an across-the-board pay raise is very expensive,5 they tend to be an efficient solution to recruiting and retention problems that are skill-specific. For example, the Services may offer enlistment bonuses of $5,000 to $8,000 to qualified recruits in selected occupational specialties.

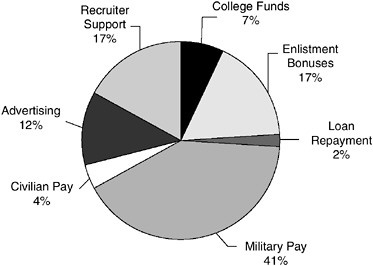

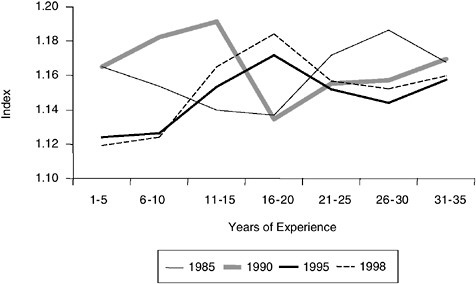

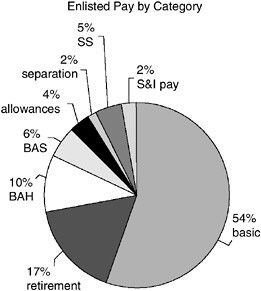

Special and incentive pays constitute only a small portion of the total cash compensation package. Although they are especially effective in targeting and alleviating specific recruiting and retention problems, because they are such a small proportion of total compensation, their influence is limited by their relatively modest proportion of total compensation. Figure 5-2 shows the distribution of cash compensation (including deferred retirement pay) for enlisted personnel.

FIGURE 5-2 Distribution of cash compensation: Enlisted personnel.

SOURCE: Paul F. Hogan and Pat Mackin, Briefing to the Ninth Quadrennial Review of Military Compensation Working Group, November, 2000.

NOTE: BAH = Basic Allowance for Housing; BAS = Basic Allowance for Subsistence; SS = Social Security; S&I = Special and Incentive Pay.

The military retirement system is a major component of total compensation. Those members who entered prior to 1980 are eligible to receive 50 percent of basic pay at the time of retirement if they retire with 20 years of service, rising linearly to 75 percent of basic pay with 30 years of service. Those who entered between 1980 and 1986 may retire under similar conditions, except that their annuity is based on an average of their highest three years of pay. Finally, those who entered after 1986 now have a choice to either (1) receive the same annuity as those who entered between 1980 and 1986 or (2) accept a $30,000 lump sum at 15 years of service and receive 40 percent of an average of their three highest years of pay at 20 years of service, rising linearly to 75 percent at 30 years of service.

The military retirement system is relatively generous. It has a dominant effect on retention after the second term of service. However, because of the “cliff” vesting of the current system—the member receives nothing unless he or she stays through 20 years of service—it is not a major factor in recruiting.

Benefits

In addition to housing and subsistence allowances, which may be provided either as cash or an in-kind allowance, there are numerous other in-kind benefits of military service.

Military members themselves receive medical and dental benefits at no cost from military treatment facilities. Dependents receive medical benefits through TRICARE, which offers managed care and fee-for-service (CHAMPUS) plans. The out-of-pocket costs are generally minimal and the overall benefits are competitive with plans offered by civilian employers.

The Montgomery GI Bill, which is offered to all recruits, provides resources for college, primarily to those who have left active duty service. The recruit must agree to have $100 per month deducted from pay for 12 months. In return, the member receives about $20,000 for college over a 36-month enrollment period. In addition, the Service may supplement this amount for qualified recruits in selected occupational specialties. The Army, through the Army College Fund, adds in excess of $30,000 to the benefits for qualified recruits who enlist in selected hard-to-fill occupational specialties. The Navy and the Marine Corps also offer additional education benefits, but on a smaller scale than the Army.

Recently, there have been numerous legislative proposals in both the House and the Senate to enhance the basic benefit of the Montgomery GI Bill and to add new features, such as the ability of the member to transfer all, or a portion, of the benefit for use by dependents. However, no major changes have been enacted as of this writing.

All of the Services offer a tuition assistance program for members who take college courses while on active duty. Typically, this program will reimburse 75 percent of the cost of college credit hours taken by members while on active duty.

In addition, there are numerous other benefits of military service. These include access to recreational facilities ranging from gymnasiums and bowling alleys to the opportunity to fly free on a space-available basis on military flights. Members also receive all of the benefits associated with veteran status, including the ability to obtain a VA mortgage while on active duty.

Finally, many military members serving in particular occupations receive training and experience that is transferable to the civilian sector. While not a benefit in the traditional sense, this training and experience are valued highly in the civilian labor market. The evidence in the research literature is consistent with intuition (e.g., Stafford, 1991; Goldberg and Warner, 1987). On one hand, in occupations that require technical skills and other occupations, such as health care, with a clear counterpart

in the civilian sector, military training and experience are about as valuable as training and experience in the occupation in the civilian sector. The advantage to the military members is that they receive this training at no cost to themselves while earning full pay on active duty.6 On the other hand, in the traditional combat arms occupational specialties, as well as in other occupations that are relatively military-specific, training and experience have a positive effect on potential civilian earnings, but not as large an effect as the equivalent amount of civilian labor market experience.

Competitiveness of Military Compensation and Benefits7

The adequacy of the military compensation package is ultimately determined by its ability to attract and retain sufficient qualified staff to maintain readiness levels. Generally, to do this, military pay must at least compensate members for what they could be earning in the civilian sector, given their actual level of education. Moreover, recruiting requires that some proportion of high school graduates who are in the upper half of the distribution nationally on an intellectual qualification test choose to enter the military rather than college. Arguably, because these potential recruits could have gone to college, military pay must compensate them for what they could have earned in the civilian sector, had they gone to college. Because not all would have completed college, at a minimum it should compensate members for what they could have earned with “some college.” Indeed, as reported in the Department of Defense (DoD) Personnel Survey for 1999, over half of enlisted personnel and 80 percent of enlisted members with more than 20 years of service report that they have completed at least one year of college (see Asch et al., 2001).

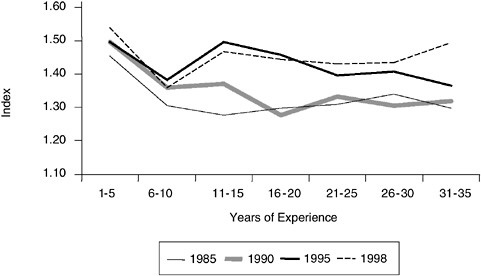

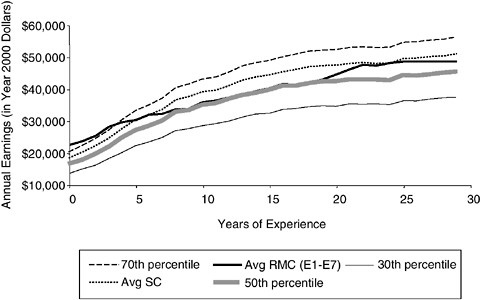

Figure 5-3 compares average enlisted regular military compensation (RMC) to the earnings of civilians with some college. Recall that RMC includes basic pay, allowance for subsistence, the housing allowance, and the tax advantage on the allowances. RMC is the standard measure of military cash pay to compare with civilian cash earnings. Average RMC is about at the same level as median earnings reported by those with some college and comparable experience and below average earnings for that group. Average RMC is significantly below those at the 70th percentile of

FIGURE 5-3 July 2000 enlisted pay (regular military compensation or RMC) compared with predicted year 2000 earnings of males with some college (SC).

SOURCE: Asch et al. (2001).

civilian earnings for those with some college. Because most military members are in the upper half of the intelligence distribution, as measured by the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT), those in the 70th percentile of civilian earnings are arguably the most relevant comparison group.

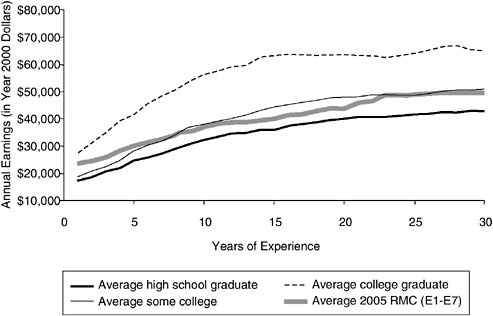

Many who enlist could have entered a four-year college and completed an undergraduate degree. Their earnings in the enlisted force would be significantly below the average earnings of college graduates. Figure 5-4 compares average RMC, projected to FY 2005 to average earnings in the civilian sector, at various levels of education, also projected to FY 2005 (Hogan and Mackin, 2000). Note that the difference in earnings between college graduates and high school graduates is quite large, as is the difference between college graduates and those with some college. The returns from completing four years of college appear to be quite substantial. Enlisted pay, as measured by average RMC, does not appear to be competitive with the pay of college graduates.

These pay comparisons suggest that if the Services are competing with the college market, recruiting will become more difficult, given the apparent earnings premium enjoyed by college graduates. Since the mid-1980s, the Services have been relatively successful in recruiting. It is only in recent years, since about FY 1997, that recruiting has become difficult again.

FIGURE 5-4 Average civilian earnings and average FY 2005 enlisted (regular military compensation or RMC) by years of experience.

SOURCE: Asch et al. (2001).

Recruiting success is typically measured not simply by numbers, but by the proportions of recruits who are highly qualified. We present two measures: the proportion of recruits who are high school diploma graduates and the proportion who are high school diploma graduates and also score in the top half of the AFQT. Data on these factors are presented in Chapter 4, this volume. The percentage of high school diploma graduates recruited by the Services has consistently exceeded about 90 percent since about FY 1984, with only the Navy falling below that level, and then only for a few years. However, while the percentage had exceeded 90 percent for the first half of the 1990s, it has fallen to 90 percent or near that for all the Services except the Air Force since about FY 1996. Similarly, while the percentage of highly qualified recruits exceeded 60 percent for each of the Services in the first half of the 1990s, the trend has been downward for all the Services since about FY 1996 and has fallen below 60 percent for the Army and Navy.

While the Services have experienced significant recruiting difficulties since about FY 1996, two related points are important to consider. First, recruiting results were extraordinarily good, as measured by the percentage of highly qualified recruits, in the first half of the 1990s. Hence, the poorer results of the second half of the decade are in comparison to the

best recruiting results in the modern volunteer force period. Much of the success of the early 1990s was due simply to the lower demand for recruits during the post-cold war drawdown of forces. Second, compared with the 1970s and most of the 1980s, the results in the second half of the 1990s through FY 2000 are relatively good.

Incentives and Resources Affecting Recruiting

The military environment, military compensation, and in-kind benefits all affect the desirability of enlisting. In addition, the Services and DoD allocate resources directly to improve recruiting. The largest share of the recruiting budget is for military recruiters—the recruiting sales force. In addition, the Services provide targeted incentives to recruits with certain qualifications who enlist in selected occupational specialties. These include enlistment bonuses, which can be as high as $8,000 and are paid on successful completion of initial skill training, and supplements to the Montgomery GI Bill, which can be as much as $30,000. Finally, the Services spend resources on advertising, both to inform potential recruits about opportunities in the military and to convince them to enlist.

The state of the economy has an important effect on the supply of recruits. When the economy is strong, with low unemployment, recruiting becomes more difficult. More recruiting resources are required to achieve a given recruiting goal. Similarly, during economic downturns, recruiting becomes somewhat easier. Fewer resources are required to achieve a given recruiting goal.

The effect of recruiting resources on enlistments is sometimes summarized in a measure called an “elasticity.” In the context of recruiting, elasticity indicates the percentage increase in recruits one can expect when a particular recruiting resource or factor increases by 10 percent. If the elasticity of enlistments with respect to recruiters is 0.5, for example, a 10 percent increase in recruiters would result in a 5 percent increase in enlistments.

In Table 5-3, we summarize the range of elasticities found in the recent econometric literature on military recruiting (e.g., Hogan and Dall, 1996; Hogan et al., 1998; Murray and McDonald, 1999; Warner et al., 1998). Although there has not been a large number of studies on recruiting in the 1990s, these studies use methods that build on and, in many cases, improve on the more numerous studies of the 1970s and early 1980s. In almost all cases, the elasticity is measured with respect to highly qualified recruits, a group that is in demand at the margin. The estimates vary by Service, time period of the data, and, in some cases, methods used to estimate effects. The estimated elasticities are statistical estimates ob-

TABLE 5-3 Elasticities of Enlistments with Respect to Various Recruiting Resources

tained by treating the observed variation in recruiting results and resources as a natural experiment.

An elasticity provides a measure of the importance of the factor on recruiting. However, it is not a cost-benefit analysis. Advertising, for example, has a small elasticity, but the advertising budget itself is small compared with the budget for recruiters. Hence, it is not correct to judge cost-effectiveness of the resource by the elasticity.8Table 5-4 provides an estimate of the costs associated with recruiting one additional highly qualified recruit using various incentives and methods (Warner, 2001; Warner et al., 2001). The marginal cost estimates of the major recruiting resources—recruiters, education benefits, enlistment bonuses, and advertising—are generally within a few thousands of dollars of each other. This is what one would expect if all the resources are being used reasonably efficiently.

TABLE 5-4 Marginal Cost Estimates of Major Recruiting Resources (in thousands)

|

|

Service |

|||

|

Factor |

Army |

Navy |

Air Force |

Marine Corps |

|

Pay |

$32.0 |

$30.0 |

$40.8 |

$59.0 |

|

Recruiters |

$13.2 |

$8.2 |

$3.3 |

$9.3 |

|

Educational benefits |

$7.4 |

$12.0 |

||

|

Enlistment bonuses |

$12.0 |

|

||

|

Advertising-Total |

$9–11.0 |

$7–8.0 |

||

|

Advertising-TV |

$7.0–9.3 |

$7.3 |

||

|

Advertising-non-TV |

$3.8–8.4 |

$2.7–4.7 |

||

|

SOURCE: Warner et al. (2001). |

||||

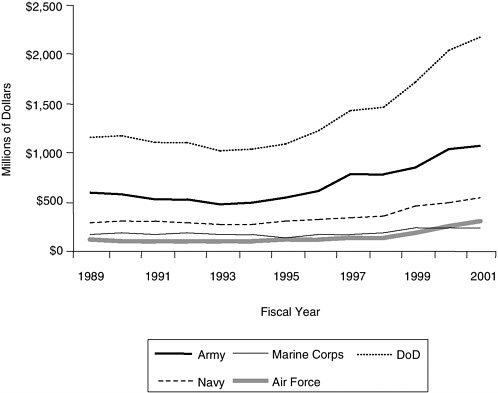

The table provides a measure of the effect of various resources (and environmental factors) on recruiting. Table 5-5 provides an indication of the budgets and changes in these budgets over time. Note that military pay, the largest single budget item, is largely pay and allowances for recruiters. Since about FY 1997, recruiting resources have increased significantly, particularly for the Army (see Figures 5-5 and 5-6).

Econometric models of enlistment supply, such as those of Warner et al. (2001), can provide insights into an important question: Given the estimated effects of recruiting resources and the economy on enlistment supply, can changes in these resources and changes in the economy explain the decline in enlistments in the late 1990s, or is the decline due to

TABLE 5-5 FY 2001 Recruiting Budget (in millions)

|

|

Army |

Navy |

Air Force |

Marine Corps |

DoD |

|

College funds (NCF) |

$101.62 |

$28.18 |

|

$29.42 |

$159.22 |

|

Enlistment bonuses |

$147.40 |

$105.12 |

$116.34 |

$7.44 |

$376.30 |

|

Loan repayment |

$32.89 |

$0.10 |

$6.00 |

— |

$38.99 |

|

Military pay |

$409.60 |

$252.05 |

$96.04 |

$119.87 |

$877.57 |

|

Civilian pay |

$47.57 |

$24.55 |

$8.76 |

$7.77 |

$88.65 |

|

Advertising |

$102.04 |

$66.39 |

$47.86 |

$38.65 |

$254.94 |

|

Recruiter support |

$225.23 |

$70.31 |

$35.21 |

$43.01 |

$373.75 |

|

Total |

$1,066.35 |

$546.70 |

$310.21 |

$246.16 |

$2,169.42 |

|

SOURCE: Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (2001). |

|||||

other, as yet unidentified, factors? Warner et al. accounted for changes in the economy, resources, and the effectiveness of resources. Based on their analyses, Warner and his colleagues conclude the following:

We do not believe that the downward trend in high-quality enlistment since 1993 can be attributed to shifts from the past in the way recruiting responds to economic factors (pay and unemployment) and it is not explained by diminished effectiveness of recruiting resources. Specifically, we do not find that the responsiveness of enlistment to either recruiters or advertising has declined. Positively, we also find that recruiting is responsive to educational benefits and enlistment bonuses. However, the effectiveness of Army College Fund benefits may have declined due to a large expansion in Army enlistment bonuses since FY 1997. Expansion in college attendance accounts for some of the decline in high-quality recruiting but is not the end of the story. There remains a significant negative residual component to recruiting that appears to be the result of a decline in youth tastes for military service. Understanding the reasons for the decline in youth tastes for service, and policy options for responding to it, would be an important avenue for future research.

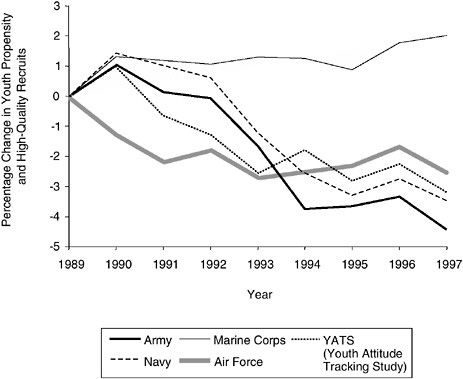

In particular, Warner and his colleagues note that the unexplained portion of the decline in highly qualified recruits (the portion of the decline that cannot be explained by changes in resources, the economy, or the effects of resources and the economy on enlistments) tracks the decline in youth propensity as measured by the Youth Attitude Tracking Survey (YATS). This is illustrated in Figure 5-7.

Possible sources for youth propensity and its changes over time that are not typically captured in econometric models are altruistic motives to enlist. One form of these motivations, patriotism, is briefly discussed in the next section.

Patriotism and Higher Purpose

We have discussed the financial rewards of military service, in-kind benefits, and the hardships and risks associated with military life. One aspect of military service that differs from most civilian jobs is that there is a higher purpose to military service than simply receiving pay and benefits in return for work and the acceptance of hardships. Patriotism and selfless service to one’s country provide a potentially strong motivation to enlist (as discussed in Chapters 7 and 8, this volume). While such sentiments cannot fully compensate for noncompetitive pay and unpleasant working conditions, they do provide a foundation for recruiting and retaining motivated staff that is generally unavailable to civilian-sector employers. Moreover, as suggested in the previous section, changes in

FIGURE 5-7 Normalized male YATS propensity and unexplained recruiting trend.

SOURCE: Warner (2001).

more altruistic motivations for service can have an important influence on recruiting.

Summary

Enlistment in the armed forces is one of three major options eligible youth have upon completion of high school. The armed forces offer a lifestyle that is very different from the one most recent high school graduates experience in college or in civilian employment. Typically, the individual leaves his or her hometown and is subject to military orders and discipline. These orders may, in fact, place the individual in harm’s way.

To attract recruits, the armed forces offer a complex but generally competitive system of pay, allowances, bonuses, and benefits to compete with civilian alternatives. In addition, they use a reasonably efficient mix of various recruiting resources, including bonuses, advertising, and recruiters. Finally, the rate at which youth continue to go to college has

grown over time.9 The armed forces offers postservice education benefits (in the form of the Montgomery GI Bill and augmentations to it) to attract those recruits who also have college aspirations.

Recruiting has become increasingly difficult since the second half of the 1990s. This was due, at least in part, to an improving economy through 2000 and to a decline in recruiting resources in the mid-1990s. However, while these factors can explain some of the decline, a portion remains unexplained. It is unclear whether this represents a change in tastes or preferences for military service on the part of American youth or is due to other factors that simply are not captured in econometric equations. Success in the recruiting market now and in the future will require that compensation and benefits remain competitive with those offered in the civilian sector, that other recruiting resources be applied efficiently and in proportion to the recruiting mission, and that innovative ways to combine military service with the pursuit of higher education are offered. Finally, military service offers youth a higher purpose, in the form of duty to country, service to others, and self-sacrifice, that is rare in other alternatives. The armed forces should not neglect this aspect of military service in its recruiting efforts.

THE EMPLOYMENT ALTERNATIVE

Employment in the civilian sector is a major source of competition to the military services. Although a small proportion of the civilian labor force works in the public sector and is employed by a governmental organization, a far greater proportion is employed by private industry. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2002b) estimates that 212 million people age 16 and older make up the civilian noninstitutionalized population; in contrast, the U.S. Bureau of the Census (2000b) reported 17 million people employed by federal, state, and local governments. Because the number of job opportunities is far greater in the private sector, our discussion primarily focuses on individuals employed in the private sector. When appropriate, examples from the public sector are included.

In general, the term “civilian” in this section refers to people employed in nonmilitary settings, while “private” and “public” sector refer to private industry or government employment, respectively. This section also provides brief descriptions of the common practices used in the private-sector labor market and compares employment opportunities in private industry to opportunities in the military at general levels. We provide

general information regarding entry-level private-sector employment, a description of the current labor market, the perceived benefits and liabilities associated with employment in private industry, and comparisons of various aspects of military service and private-sector employment.

Comparing the private-sector employment option to military service is difficult because of the many variations in civilian employment processes and opportunities. Differences among entrance and hiring practices, compensation strategies, benefit programs, education and training options, and working conditions vary across different industries and organizations. Moreover, such variables as the size of the organization, industry type, job family, presence or absence of labor unions, and geographical location also affect the civilian labor market. Even when the job or type of work is held constant, opportunities in private-sector employment are highly varied. While the military Services offer similar benefits and rewards for the same job level, the civilian sector may offer different compensation and benefits for the same job depending on the organization, industry, location, etc.

It is important to remember that slightly more than half of Americans work in companies with fewer than 500 employees and almost 20 percent work in firms with fewer than 20 employees. The jobs and associated opportunities in these smaller firms may be significantly different from those in larger firms. While the military may be more like the largest companies, only 3,316 of the 5,541,918 firms in the United States had over 2,500 employees (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999) and approximately 37 million of the 105 million U.S. employed work for these firms.

Yet another difficulty in comparing occupations across civilian and military settings is defining what jobs are similar across those settings and what jobs are different. For example, while the military may not have Internal Revenue Service (IRS) agents, the military does have personnel who engage in audit functions similar to the duties that might be performed by an IRS agent. Similarly, the military may lack a merger and acquisitions specialist, found in some large organizations, but it does have individuals who use similar skills to analyze situations and organizations. Thus, questions about the degrees of similarity in jobs and tasks as well as environment must be asked if meaningful comparisons are to be made.

Further complicating a comparison of civilian opportunities in the private sector and military opportunities are the continuous changes in the external contexts of work (e.g., markets, technology, and workforce demographics), the organizational contexts of work (e.g., organizational restructuring and changing employment relationships), and the structure and content of work (National Research Council, 1999). The National Research Council report The Changing Nature of Work noted many changes

that affect the actual content of a job. For example, the increasing use of teams has flattened organizational hierarchies, and teams are often given greater discretion over how work is performed. The report also pointed out that few trends were universal and cited as an example decreasing discretion in some jobs in the service and manufacturing sectors, in which rational processes and information systems are used to control the work.

In sum, there is enormous variability in processes and opportunities both across and within industries, organizations, and jobs. Considering the variability mentioned above, it is impractical to try to describe and compare all possible variations in organizational processes and employment options. Much of the research in these areas is limited to private-sector market research, general polls, and organizational surveys (e.g., American Management Association, 2001; Society for Human Resource Management, 2000). Moreover, the empirical literature on civilian employment is not scientifically sound or readily available. However, when available, we cite relevant sources of information on employment in the civilian sector (e.g., National Research Council, 1999; Office of Management and Budget, 1997; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999a, 2001, 2002a, 2002b).

Demographic Trends: Who Chooses Employment?

Of the 212 million people in the civilian population in 2001 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002b), over two-thirds (142 million or 70 percent) participated in the civilian labor force. Participation in the labor force varied little among race and ethnic groups. However, participation was higher for men than for women; specifically 74 percent of males age 16 and over participated in the labor force compared with 60 percent of females.

About half of all youth ages 16 to 19 participated in the civilian labor force in 2001 (approximately half male and half female; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002b). A majority (77 percent) of those ages 20–24 participated in the labor force (82 percent male and 73 percent female).

The labor force is projected to increase by 17 million to 155 million people in 2008, a 12 percent increase from 1998 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999b). Among race-ethnic groups, participation rates for Asians and Hispanics are projected to grow the most compared with blacks and non-Hispanic whites. The rate of participation for men in the labor force is expected to increase, but at a slower pace than in the previous decade. For women, the participation rate will surpass that of men. Older workers ages 45–64 are expected to show the highest growth (spurred by the baby boom generation of workers), but the youth population is also projected

to increase over the next several years, leading to rapid growth in the youth labor force.

Participation in the labor force typically increases with level of educational attainment (Table 5-6). In 2001, college graduates (25 and older) participated in the labor force at the highest rates (79 percent) compared with high school graduates (64 percent) and persons who did not complete high school (44 percent). The participation rate for male college graduates was 85 percent compared with 73 percent for female college graduates (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002b). For male and female high school graduates, participation rates were 74 and 56 percent, respectively. Blacks and whites with a high school degree participated in the labor force at lower rates (69 percent and 64 percent, respectively) compared with Hispanic graduates (74 percent).

Together, these data indicate that a number of high school graduates do not participate in the civilian labor force immediately after graduation or in the years thereafter. Instead, they may potentially choose among other options such as time off, postsecondary education, or military service.

Employment Opportunities in the Private Sector: An Overview

The array of jobs in the private sector can be classified into different categories. This overview describes the systems used to classify different occupations and presents a simple analysis of jobs found in the military versus the civilian sector. The National Research Council (1999:165) provides a detailed discussion of job classification systems and defined occupational analysis as “the tools and methods used to describe and label work, positions, jobs, and occupations”. The report reviewed three kinds of systems: (1) descriptive/analytic systems, (2) category and enumerative systems, and (3) systems that combine the two. Of the common enumerative systems, the most important is the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system, which is intended to be the primary occupational category system used by federal agencies (Office of Management and Budget, 1997), including the Census Bureau for the 2000 census and the Department of Labor for the Occupational Information Network or O*NET project.

A combination of the descriptive and enumerative approaches is embodied in the O*NET. O*NET was developed by the U.S. Department of Labor to provide employers, job seekers, career counselors, government workers, occupational analysts, researchers, and students computerized access to the database of occupational information. O*NET occupational profiles provide an overview based on 445 variables, such as worker characteristics, worker requirements, experience requirements, occupation

TABLE 5-6 Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population 25 Years and Over by Educational Attainment, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin, 2001 (in thousands)

|

Household Data Annual Averages Educational Attainment |

Total |

Men |

Women |

White |

Black |

Hispanic Origin |

|

Total |

|

|||||

|

Civilian noninstitutional population |

176,839 |

84,294 |

92,546 |

148,021 |

20,333 |

17,850 |

|

Percentage in the civilian labor force |

67.4 |

75.9 |

59.7 |

67.1 |

68.2 |

69.7 |

|

Less than a high school diploma |

|

|||||

|

Civilian noninstitutional population |

27,790 |

13,195 |

14,595 |

22,250 |

4,241 |

7,736 |

|

Percentage in the civilian labor force |

43.6 |

55.6 |

32.7 |

44.2 |

40.0 |

59.4 |

|

High school graduates, no college |

|

|||||

|

Civilian noninstitutional population |

57,367 |

26,542 |

30,825 |

48,277 |

7,094 |

4,911 |

|

Percentage in the civilian labor force |

64.4 |

74.4 |

55.8 |

63.6 |

69.2 |

73.9 |

|

Some college, no degree |

|

|||||

|

Civilian noninstitutional population |

30,529 |

14,300 |

16,229 |

25,441 |

3,968 |

2,281 |

|

Percentage in the civilian labor force |

71.9 |

78.9 |

65.8 |

70.8 |

78.0 |

80.2 |

|

College graduates |

|

|||||

|

Civilian noninstitutional population |

46,601 |

24,002 |

22,599 |

39,754 |

3,411 |

2,005 |

|

Percentage in the civilian labor force |

79.0 |

84.4 |

73.3 |

78.7 |

83.7 |

82.1 |

|

SOURCE: Data from Table 7, Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population 25 Years and Over by Educational Attainment, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin, 2001 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2002b). |

||||||

requirements, occupation characteristics, and specific occupational information. Each of these is further broken down into meaningful categories. Detailed information about employment opportunities referenced in the O*NET are available at www.onetcenter.org.

When comparing private-sector jobs and military positions, one finds

that not all military jobs are represented in the civilian sector and not all civilian jobs are found in the military. For example, military jobs related to warfare, such as armored assault vehicle crew members, artillery and missile crew members, and infantry, are not found among civilian jobs; civilian jobs like teaching the disabled are not found in the military. In the SOC system, which is linked to O*NET, 1 of the 23 major occupational groups contains occupations specific to the military. The implication of this observation, consistent with the literature briefly reviewed in the previous section on the value of military experience in the civilian sector, is that military service for the purpose of job training that will enhance the chance of successful employment in a civilian position may not be as valuable if the military assignment is in a field that does not have a civilian counterpart.

However, also consistent with the literature, many employers recognize that military service builds many job-related skills even when the actual work performed is not related to the civilian job. Basic skills like teamwork, following directions, and record keeping may be common to most jobs regardless of the nature of the work or the environment in which it is performed.

Many jobs are found in both the military and the private sector. Of the other 22 SOC major groups, all have a military counterpart in some form. The large number of jobs that are found in both the military and the civilian job market indicates that military service may provide job-specific training in many occupations that will facilitate later civilian employment.

The extent to which military and private-sector jobs overlap is difficult to assess without comparing specific jobs in a military service and in a particular organization. However, at a more macro level, comparisons have been made. The current military career guides, available at www.todaysmilitary.com, suggest about an 88 percent overlap of jobs based on analyses from the Defense Manpower Data Center (Today’s Military, 2001). These are more likely to be jobs in health care, service and administration, and electrical and machine equipment repair (Gribben, 2001). However, the distribution of personnel in military occupational areas shown in Table 2-5 indicates that almost 17 percent of personnel were in infantry alone in 2000, an occupation with no direct counterpart in the civilian sector. Furthermore, the Army and the Marine Corps have more personnel assigned to infantry positions.

Occupational Trends

Gribben (2001) did an analysis of occupational trends in the civilian sector and in the military; she reported noticeable shifts in the occupa-

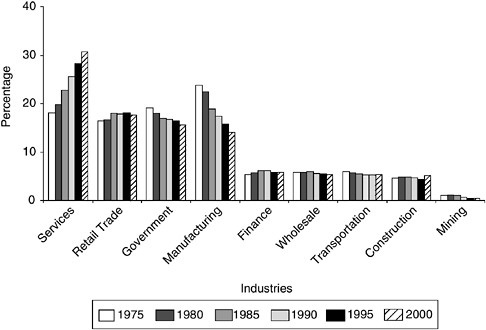

FIGURE 5-8 Civilian industry trends, FY 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000.

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2001).

tional mix of jobs in civilian employment. Between 1975 and 2000, the proportion of jobs in the service industry grew from 18 to 31 percent of all civilian positions, while manufacturing jobs decreased from 24 to 14 percent of all positions (see Figure 5-8; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2001). Government employment also decreased somewhat during the same time period, from more than 19 percent in 1975 to less than 16 percent in 2000. Other industries, such as construction, retail trade, and finance, accounted for about 30 percent of all jobs. These industries did not show appreciable changes in their proportion of the labor market during this time period.

Job growth during the 10-year period 1998–2008 is expected to continue particularly for service employees and professional specialty occupations (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1999a). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects the following as the 10 fastest-growing occupations for 1998–2008:

-

Computer engineers

-

Computer support specialists

-

Systems analysts

-

Database administrators

-

Paralegals and legal assistants

-

Personal care and home health aides

-

Medical assistants

-

Social and human service assistants

-

Physician assistants.

Demand for Workers

Although there is some military-civilian overlap in high-growth occupations (e.g., health care, service, administration, equipment operation and repair), current and projected trends in the civilian occupational distribution do not precisely mirror the trends in military distributions. Moreover, occupational mix requirements and the demand for workers in different occupations vary between the civilian and military sectors. In the military during the past 25 years, there has been a slight trend toward more technical occupations, such as electronic equipment repair, and communication and intelligence (Gribben, 2001). Service and supply handlers and functional support and administration specialists play a smaller role in the mix of occupations. During the period FY 1976–2000, there was a tremendous need for electrical and mechanical equipment repair specialists in the military along with a large contingent of infantry and related positions.

Military and civilian jobs are categorized by the SOC system. Civilian labor market opportunities depend on the mix of available jobs and demand for specific occupational areas. Though occupational trends have shown significant shifts in certain areas in civilian employment (particularly professional and service occupations), changes have been smaller and more gradual in the military. We have described the opportunities available in the civilian sector. Next, we turn to entry into occupations in each sector and compare the different selection processes and standards.

Labor Market Access

As described earlier in this chapter, the military has clearly defined processes and standards for entry into each service. In contrast, processes and standards in the private sector vary across companies and industries. For example, some employers have no defined processes or standards at all; the employer decides how to hire when a position becomes available and an applicant appears and may use selection methods with little relationship to the requirements of the job (e.g., likeability of candidate in the interview). Such employers may change hiring practices for different jobs and even for candidates for the same positions, setting standards for hiring only after a suitable candidate has been identified. At the other ex-

treme, other employers have specific hiring processes and standards as clearly defined as those of the military (e.g., the U.S. government). In between, there are significant variations in selection processes and standards, even for the same jobs within an organization.

All entrants to military service are subject to a centralized job classification procedure based on the results of the ASVAB. This is not the case in the private sector. Even when required skills are common across jobs and organizations, employers differ in how they assess those skills. For example, one organization may assess the cognitive ability of an applicant by administering a professionally developed and validated paper-and-pencil test, while another may assess cognitive ability by reviewing the applicant’s resume and evaluating his or her educational achievement. In 2001, 29 percent of private-sector companies used some form of psychological measurement to assess applicants (American Management Association, 2001). In addition to cognitive ability assessments, which are used most frequently (20 percent of respondents), interest inventories, managerial assessments, personality assessments, and task simulations may be used in the private sector. However, the number of organizations using any form of psychological tests other than basic screening is low and dropping.10

Organizations also differ on what knowledge, skills, and abilities they choose to assess. As described in O*NET, they range from basic writing skills to complex problem-solving skills, from knowledge in general domains to specific occupational knowledge and experience, and from physical to cognitive abilities. Even if the identical job with the same requirements exists in two different organizations, finding one organization that measures and selects on cognitive ability and another on “professional appearance” is not uncommon.

The degree of variation and lack of standardization across U.S. companies is reflected in data collected by the American Management Association. It surveyed human resource managers in their member and client companies in January 2001 (American Management Association, 2001). Based on 1,627 usable responses with a margin of error of 2.5 percent, the findings showed that several companies used formal selection processes like literacy testing in 2001 (35 percent), while large numbers did not. Responses also illustrated different testing practices—literacy testing,

math testing, or both—across industries (e.g., financial services versus wholesale and retail).

In addition to ensuring that recruits have the basic skills and abilities to learn and perform their military occupations, the military imposes other standards related to age, citizenship (or permanent residency), education, physical fitness, dependency status, and moral character. Most private employers avoid use of such standards because of the inherent conflicts with federal, state, and local equal employment and disability laws that protect individuals from discrimination on the basis of race, sex, age, and other variables that define a protected class of individuals. However, some jobs may require the applicant to submit to background checks, meet medical or physical requirements, or obtain certifications or licenses, similar to processes used in the military.

Some characteristics like education and moral character are used in the private sector for selection if they are job relevant. Although the practice might be questioned from a legal defensibility point of view (e.g., most organizations are not able to demonstrate a significant relationship between having a high school diploma and job performance), it is not uncommon for an employer to require a high school diploma. However, it is important to note that the usual question private employers ask is whether a person possesses a high school diploma or the equivalent, not whether a person has a GED instead of a high school diploma. Alternatively, organizations sometimes recruit applicants only at places that are likely to provide high school graduates (e.g., job fairs associated with a vocational-technical school). Because some characteristics like having a GED are correlated with other variables that constitute a protected class (e.g., race), most employers avoid making inferences about the kind of individual who earns a high school diploma and the kind who earns a GED.

Comparing the processes for entrance into the military and private-sector employment, there are two apparent differences. First, the standards and processes by which individuals are selected into military occupations are known and widely communicated. In contrast, the standards and processes used to staff jobs in business and industry are highly variable across and within organizations. While personnel in the staffing division of the organization (if they exist) usually know the processes and standards, in many organizations, these processes and standards are often not publicly communicated to other personnel. Although applicants will learn of the process through experience, the standards required are sometimes never explicitly stated.

Second, because of the federal, state, and local laws, civilian employers often may not use personal characteristics like age, physical ability, and dependency status. In fact, some companies avoid any questions

regarding these characteristics until after making a job offer. In contrast, these are primary criteria for military qualification.

Training Opportunities

Once an applicant is selected or hired into an entry-level position, the organization may provide training. Organizations vary considerably in their approaches to training. Some companies consider training to be an on-the-job effort and expect employees to learn by doing. So, in an entry-level job, a new hire may only attend a general orientation on the first day of employment and no other training. Other organizations devote considerable resources to providing formal training and evaluating competence (e.g., mentoring, staff development, technical training). Still others sidestep training altogether and hire only experienced employees for positions that require some training.

Organizations also vary on the kinds of training that are offered. While the military offers military training (e.g., basic training and occupational skills training) to all Service members, many private-sector employers provide basic skills training and supervisory training to only a few. The extent to which kind and amount of training are provided is unknown in the private sector as a whole. Similarly, outcome variables like standards and required competency levels are usually not specified.

Many employees are expected to invest in acquiring skills though postsecondary and vocational education and training courses prior to entry. When such general skills training is provided by business or industry, the employee often receives a reduced training wage although the employee may receive reimbursement for tuition. In contrast, the military provides fundamental job training in basic and advanced skills, such as electronics, computer science, and nuclear power, while the recruit continues to earn a salary. Training opportunities are available in some organizations for some occupations; in the military, training is offered to all recruits.

Working Conditions

To attract highly qualified and skilled employees, employers in private industry emphasize various inducements, such as attractive work settings (e.g., location, amenities, firm size), competitive compensation and benefits, advanced technology, career development, and training. For many job applicants, one of the most important aspects considered when choosing an entry-level position is working conditions.

While many positions in the civilian work force do not seem to vary substantially from similar positions in the military on skill or training

requirements, there may be substantial differences between working conditions in military and civilian-sector jobs. Some variables that differ include leisure time, level of supervision, autonomy, union membership, personal safety, work/family issues, culture, and commitment.

Unlike serving in the military, working in entry-level jobs may not require a contract with the employer or strict adherence to rules that govern almost all aspects of one’s life. A notable exception is certain jobs in local, state, or federal government. However, civilian employees are subject to organizational rules and regulations regarding such things as work hours (e.g., night shifts for security guards), dress code or uniform requirements (e.g., delivery drivers), and personal behavior (e.g., customer service agents). Nevertheless, in most cases, entry-level employees have more freedom to choose where to live and how to spend their free time compared with military personnel.

Not only are military personnel subject to military orders and discipline; they may serve under onerous conditions and in unpleasant places and may be subject to the risk of physical injury or death in combat. In some civilian occupations, conditions may be similarly undesirable or unpleasant. For example, police officers and firefighters risk their lives to ensure the safety of the people in their communities. With the exception of jobs in law enforcement and safety, however, most entry-level jobs are inherently low-risk, and none involves combat in warfare. Other work conditions may be less risky but have undesirable components, such as separation from family and night-shift duty.

The working conditions in the military and civilian employment vary considerably; however, it is important to note that it is the value an individual places on a specific working condition that is important in determining whether it is an advantage or disadvantage in the employment decision. What may be undesirable to one individual may be particularly attractive to another. While some may find the conditions of combat terrifying, others may find the same situation exhilarating. For some, night-shift work may be valued because it allows parental child care that would be precluded if both parents worked day hours.

Compensation

Like other human resource practices in the private sector, compensation strategies vary across and within different organizations, jobs, job families, and labor contracts. While the military has a fairly straightforward pay scale based on enlistment grade and various bonuses, private firms often use a complex array of recurring salaries or wages, merit increases, longevity increases, performance bonuses, and wage credits as

well as benefits with direct financial value (e.g., pension plans, savings plan match).

Compensation of entry-level employees typically includes a base salary, incentive pay, awards, and other rewards. In addition, entry-level employees often receive overtime pay for hours worked over 40 in a week or on holidays. Compensation is often determined through job analysis (e.g., comparison with market data, comparison with other jobs, manager interviews, site visits), job description (e.g., the nature and level of the work), job evaluation (e.g., job content, market drivers), and compensation strategy and resources. General wage increases usually occur either annually or semiannually.

Many employees receive incentives in addition to regular pay. Awards and other rewards include cash and noncash prizes for performance, attendance, service, stock plans, and retirement. Wage credits (based on experience), signing bonuses, and referral bonuses are frequent hiring practices. Recent trends that affect compensation are the competitive labor market, retention challenges, and performance-based plans.

Perhaps the most notable difference in compensation for military and private-sector work is the pay practices of each group. Private employers offer wider ranges of pay within smaller groups of individuals, and their practices often indicate a philosophy of rewarding those who make greater contributions (e.g., pay for performance). Pay ranges may vary as a result of wage credits given at entry for previous experience, merit increases based on superior performance, performance bonuses based on individual or team efforts, increases for tenure, credits for high cost-of-living areas, and more generous collective bargaining agreements.

Private employers take into account labor market conditions when setting pay. Most large organizations have compensation plans and a supporting organization to review and set pay scales. There are no laws other than the equal pay laws forcing private employers to pay at a given rate. The implicit limitations on pay rates come from concerns about profits, labor market rates, internal equity, and overall fairness. Private firms are free to change pay rates to meet changes in the marketplace.

In locations where the labor market is tight, such as in major metropolitan areas versus rural areas, organizations may increase pay. According to LinemenOnline, an Internet site that collects pay scales of linemen working for electrical utilities from around the world, linemen for Virginia Power are reported to make $25.62 per hour, while linemen for Tucson Electric Power Company in Arizona make $28.88 per hour (LinemenOnline, 2001). Private employers may also compete and pay more for highly desirable skills, like computer skills, than for common or easily learned skills, like administrative support skills. Although the military

also considers labor market conditions, it is on a much more limited basis (it sets one base pay rate that is congressionally approved). Thus, private companies have much more flexibility than the military Services to adapt quickly to the labor market and to reward individuals commensurate with their contributions.

In comparison, military compensation is consistent across large groups of individuals. Service members receive pay and signing bonuses for jobs that require high skills and substantial training (e.g., submarine or aviation personnel), that subject them to a high degree of personal risk, or that have shortages for any number of reasons. Thus, the pay range for everyone in a job at a particular grade in the military is very narrow.

Whether military or private-sector pay is greater overall is not clear. Some evidence regarding this was provided in the previous section. Recall that, in general, the pay of enlisted members compares favorably with the pay of high school graduates of similar age in the civilian sector, but it compares much less favorably to college graduates in the civilian sector (see Figure 5-4). However, like many other points of comparison, specific jobs in each sector should be compared. The military’s own information highlights the variability regarding pay competitiveness in a question and answer format on the Internet site, www.todaysmilitary.com:

Is military pay competitive with civilian jobs?

The answer is yes, it is. In a February 2000 survey, the Army Times Publishing Company compared 40 military positions (officer and enlisted) to their local civilian counterparts. In 19 of them, military pay was estimated to be below the local salary, but in 21 others, military pay was estimated to be equal to or higher than the comparable civilian pay. For purposes of comparison, military pay included base pay, basic allowances (housing and food), and the value of the average tax advantage for that pay grade (Today’s Military, 2001).11

One of the central questions regarding the role of compensation and military recruitment is the extent to which compensation deters (or aids) enlistments. While salary comparisons can be done for a few jobs, doing these comparisons across large numbers of jobs is quite time-consuming. Also, the data available typically compare wages across industries without accounting for differences in wages within the industry. Findings from the Army Times study mentioned in the quote above suggest that in

the aggregate there is no clear advantage to civilian employment in terms of pay. This is inconsistent with the aggregate age-education comparisons of earnings presented in the previous section, in which the comparison is with civilians who are high school graduates.

Another belief is that salary levels reach higher levels in the private sector than in the military. Many are willing to accept lower pay on a short-term basis if it leads to higher pay in the long run. Because there is generally greater dispersion in earnings in the private sector than in the military, it is likely that the financial rewards to exceptionally talented employees in the private sector are greater than the financial rewards to exceptionally talented military members.

The real issue may not be whether the actual salaries in the civilian sector are higher than those in the military or whether salaries in the private sector have a higher range. Instead, the important issue may be in how salaries are perceived by young people making decisions about enlistment.