1

Introduction

Since the mid-1990s the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has redefined its role and organization in an attempt to improve its products and service to the nation. At the USGS, there has been an increased emphasis on the “Critical Zone,” defined by the National Research Council (NRC) in its report Basic Research Opportunities in the Earth Sciences as the surface and near-surface portion of the earth system that sustains nearly all terrestrial life (NRC, 2001a, p. 35; Sidebar 1–1). This effort has included an attempt to become a revitalized component of a more inclusive natural science and information agency. By becoming a broader and more comprehensive organization, the USGS seeks the capacity to take a national leadership role by developing information and knowledge about the web of relationships that constitute the air-, water-, human-, and land-systems. To respond effectively to the challenge of providing objective, dependable information about the many science issues that affect human welfare, the USGS needs a strong Geography Discipline. In recognition of this need the USGS enlisted the National Research Council (NRC) to provide fresh perspective and guidance on future research and strategic directions for its geography program. This report distills the findings of the NRC Committee on Research Priorities in Geography at the USGS.

This introductory chapter begins with a brief description of the recent changes within the Survey. Subsequent sections in this chapter review the practice of science conducted at the Survey, outline the mission and vision statements that guide its recent reformation, and provide an overview of the report.

GEOGRAPHY AND THE CHANGING USGS

Established by Congress in 1879, the USGS was charged to describe the natural resources of the nation’s western public lands. By the early twentieth century the Survey had become one of the nation’s prominent natural science research agencies. Although geography’s role at the Survey diminished shortly after the turn of the century, USGS researchers at that time were conducting other basic theoretical research and applied problem solving that was at the cutting edge of geology, geophysics, geochemistry, hydrology, geomorphology, cartography, and (later) remote sensing.

By the 1990s, however, critics in Congress considered the USGS obsolete and proposed its abolition. A thorough public debate about the Survey and its role resulted in a dramatic revision of those proposals. USGS clients stepped forward to convince their congressional representatives that the Survey continued to serve the public. As a result, Congress decided not to eliminate the Survey but instead to broaden its purview with additional responsibilities. These additional responsibilities came with the integration of the National Biological Service and parts of the U.S. Bureau of Mines into the USGS.

|

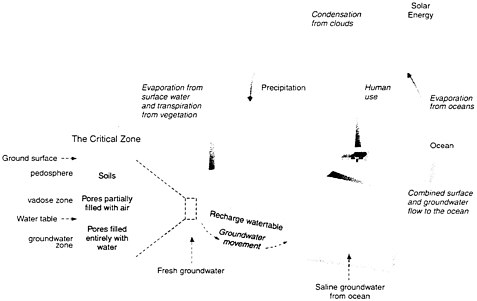

SIDEBAR 1–1 The Critical Zone: Earth’s Surface and Near-Surface Environment The surface and near-surface environment sustains nearly all terrestrial life. The rapidly expanding needs of society give special urgency to understanding the processes that operate within this Critical Zone (see figure below). Population growth and industrialization are putting pressure on the development and sustainability of natural resources such as soil, water, and energy. Human activities are increasing the inventory of toxins in the air, water, and land, and are driving changes in climate and the associated water cycle. An increasing portion of the population is at risk from landslides, flooding, coastal erosion, and other natural hazards. The Critical Zone is a dynamic interface between the solid Earth and its fluid envelopes, governed by complex linkages and feedbacks among a vast range of physical, chemical, and biological processes. These processes can be organized into four main categories: (1) tectonics driven by energy in the mantle, which modifies the surface by magmatism, faulting, uplift, and subsidence; (2) weathering driven by the dynamics of the atmosphere and hydrosphere, which controls soil development, erosion, and the chemical mobilization of near-surface rocks; (3) fluid transport driven by pressure gradients, which shapes landscapes and redistributes materials; and (4) biological activity |

|

driven by the need for nutrients, which controls many aspects of the chemical cycling among soil, rock, air, and water.  The Critical Zone includes the land surface and its canopy of vegetation, rivers, lakes, and shallow seas, and it extends through the pedosphere, unsaturated vadose zone, and saturated groundwater zone. Interactions at this interface between the solid earth and its fluid envelopes determine the availability of nearly every life-sustaining resource. SOURCE: NRC, 2001a, p. 36–37. |

This experience led the USGS, its scientists, leaders, and clients to reexamine the Survey’s range of expertise, its niche in the federal constellation of research bureaus, and its broader societal role. The Survey directly serves the natural science research needs of the Department of Interior (DOI), whose numerous agencies work toward a broad array of mission goals and objectives; however, these agencies share a need for spatial data and natural science research. The USGS meets these needs through cooperative agreements with client agencies, producing geographic information-based products and by engaging in basic and applied natural science research on problems specified by the agencies. Examples include investigations into the physical

effects of recreational use of public lands for the Bureau of Land Management, hydrologic analyses for water management decisions by the Bureau of Reclamation, and biologic studies of habitats and species for the Fish and Wildlife Service. The USGS also provides products for a variety of users outside the DOI who require mapping and other natural science data, including states, tribes, local governments, corporations, and private citizens.

The director of the USGS during the difficult years of the middle 1990s, Gordon P.Eaton, noted that the Survey persevered because of the value of its products to those who were willing to defend it. He also indicated that the inward-looking perspective of isolated researchers was no longer viable. “One lesson learned from the threat was that the viability and prosperity of the USGS depend on our ability to demonstrate the relevance of our work to society at large” (USGS, 1996). Eaton and his successor, Charles G.Groat, began a wide-ranging organizational and intellectual revision of the Survey to form a new social contract with the nation. In this new vision the USGS must respond to national and global needs by providing raw data, refined information, explanatory theories, and decision-support mechanisms to citizens and public agencies.

One outcome of this redefinition was the recognition by USGS leaders that geography again had a significant role to play in the Survey. When the USGS was first founded in the nineteenth century, geography was an integral part of its activities, but as the Survey evolved in the twentieth century away from pure description into basic earth science research, geography’s role diminished. Internationally, European scholars were delving into spatial theory, but through the 1930s, U.S. geography remained largely descriptive. In the U.S. academic community geographers and geo-logists divided into their respective scholarly camps, and geography virtually disappeared from the Survey’s activities.

By the end of the twentieth century, however, U.S. geography had academically become a powerful spatial science, and as a discipline it conducted scientific inquiry into the nature of space, place, location, patterns, distributions, and geographic flows. The discipline also included strong components related to the study of interactions between nature and society. The recognition of these potential contributions affected the reformation of the USGS. First, the newly defined Survey includes specific organizational accommodations for geography, including an Associate Director for Geography, a Chief Geographic Scientist, and a Geographic Information Officer. Second, the USGS now seeks to define and prioritize the potential bureau-wide contributions of geography in the Survey.

SCIENCE AT THE USGS

This report addresses issues related to the practice of science at the USGS. The term science denotes a way of knowing the world and a way of operating, a method of investigation with the ultimate goal of explanation and prediction. Science as a method begins with observations that may derive from field experience, theoretical manipulations, and data exploration. The collection and analysis of data then leads to classification and description, followed by questions, hypotheses, objective testing, and reporting of repeatable analyses. This series of steps in the scientific method is often so rigorous, and therefore laborious, that individuals or even organizations and disciplines may engage in only one or a few of the steps at a time. For biology, for example, more than two centuries was required to develop a descriptive classification of plants and animals before the science progressed to the next scientific step of intensive investigation and analysis. The USGS is charged to accomplish its basic mission of service to the nation through the practice of science, which requires a capability for sophisticated description, analysis, and dissemination of results.

In this report the term natural science denotes the broad range of scientific research addressed at the USGS. Natural sciences deal with the interactions, transformations, flows, distributions, and changes over time of both matter and energy. Decisions on priorities for the Survey within the natural sciences depend on the demands from other governmental agencies and society. A representative list recently published by the NRC characterizes the work of the USGS as including “geology, hydrology, geography, biology, and geospatial information sciences” (NRC, 2001b). The USGS often uses this same list in its vision statements. As the Survey becomes more involved in research addressing the nature-society interface, social processes will become more relevant to its work. In the present report the term social sciences refers to investigations of human activities, interactions, transformations, flows, and distributions, both individual and in social groups, that use the scientific method.

The reasons for specific scientific research at the USGS are based on external and internal factors. Types of studies and priorities addressed at the USGS are determined by (1) congressional intent, (2) institutional structure, (3) an agency focus on problem-solving, (4) magnitude of research projects, (5) expertise, and (6) data availability.

Congress often mandates certain research to be carried out by the USGS as part of the normal course of federal activities. This research can then be used to inform policy debate. For example, Congress has directed the Survey to conduct strategic assessments of oil and gas reserves. Alternatively, the research may provide the technical background for major public works, such

as if Congress authorizes construction of large water management projects, with the planning and design work supported by USGS generation and analysis of hydrologic data.

Institutional structure is another determinant of the Survey’s research domain. The USGS is part of the DOI, and its research first must support other DOI agencies (i.e., Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, National Park Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that manage resources but do not have a research function. These resources range from minerals, oil, and gas to water for reclamation, parks for recreation, lands for grazing, and wildlife resources. A federal division of labor between research and management also results in institutional variation in responsibilities among agencies. For example, the National Atmospheric and Oceanographic Administration (NOAA) undertakes investigations related to atmospheric and marine processes. The National Park Service manages parks, but the USGS Biology Discipline conducts research on parks.

The USGS produces problem-solving research, with topics and subjects driven by problems posed to the Survey by its clients or by federal needs. This approach is different from some other research agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), which funds many proposals for curiosity-driven research. The USGS also generates data, but such data are an early part of research at the Survey and are followed by intensive analysis, interpretation, and dissemination. This differs from agencies that are primarily or solely data producers.

Sometimes the USGS conducts research that is too large or complex for other entities to pursue. For example, geologic investigations into volcanic processes may require far more extensive instrumentation, travel, and maintenance in remote locations than universities or state agencies can provide, and projects that demand coordinated efforts of large numbers of researchers and support personnel are difficult for smaller institutions to justify. In many cases the USGS organizes, administers, and obtains funding for such efforts, with researchers from other organizations included in the effort.

In addition the USGS’s research benefits from the Survey’s personnel with special expertise. For example, the Survey’s Biology Discipline includes researchers that form a critical mass of expertise in understanding the connections between endangered species and their habitats. Although individual researchers outside the USGS have similar expertise, the Survey has a large group of researchers with strong ties to national parks and national wildlife refuges. In addition, the USGS incorporates specialized technical expertise, including the nation’s primary concentration of experts in stream gaging and earthquake monitoring.

USGS research benefits from the Survey’s long history of natural science data collection. The Survey’s databases are national treasures that define the past and present characteristics of natural systems in the Critical Zone. USGS personnel know these data, understand their complexities, and can access them better than anyone else. Because effective science relies on observations and facts, the USGS databases provide a firm foundation for the Survey’s investigations.

USGS VISION AND MISSION

Geography at the reformed USGS is part of a larger vision and mission for the Survey. The reformation of the USGS is a response to changing societal values that include more natural science requests in support of environmental quality, and devolution of federal authority with increased emphasis on service to regional and local clients. The vision and mission statements that stemmed from the Survey’s self-examination reflect these new perspectives, which the agency explicitly states as follows (USGS, 2000).

Vision. USGS is a world leader in the natural sciences through our scientific excellence and responsiveness to society’s needs.

Mission. The USGS serves the Nation by providing reliable scientific information to:

-

describe and understand the Earth;

-

minimize loss of life and property from natural disasters;

-

manage water, biological, energy and mineral resources; and

-

enhance and protect our quality of life.

These vision and mission statements give geography renewed relevance to the USGS’s redefined purposes and show that the USGS has rediscovered interest in recognizing social relevance, in understanding nature-society interactions, and in using geospatial data, which are all major themes in modern geography.

Social relevance and the connection between society and environment are especially important. Geography and geology separated in the early twentieth century as geologists became increasingly focused on earth science. At a time when geographers studied Earth as the home of humans and sought to maintain their emphasis on general relationships between societies and their environments, geology became more specialized, and thus the two

fields drifted apart both academically and at the USGS. The Survey seeks a closer association with geography to improve its approach to socially-relevant problems.

The refocusing of USGS interest on geospatial data is also a primary force in renewing geography at the Survey. Mapping has always been a primary activity at the USGS, but modern geospatial datasets go far beyond paper representations of spatial data. The ability to synthesize, display, manipulate, and analyze data directly from digital databases provide new scientific and decision-making tools that employ basic geographic principles. This combination of theory and methods results in a more complete product for the Survey’s clients and partners.

With the new vision and mission initiatives in place, the USGS asked the NRC to undertake a comprehensive study of the evolution of the Survey and its future directions. In 1998 the NRC organized the Committee on Future Roles, Challenges, and Opportunities at the U.S. Geological Survey. The committee’s recommendations helped sharpen the Survey’s vision and mission concepts with specific statements on major responsibilities (NRC, 2001b):

-

The USGS should place more emphasis on multi-scale, multi-disciplinary, integrative projects that address priorities of national interest.

-

Information management at the USGS should shift from a more passive role of study and analysis to one that seeks to convey information actively in ways that are responsive to social, political, and economic needs.

-

The USGS should provide national leadership and coordination in (1) monitoring, reporting and forecasting critical phenomena, including seismicity, volcanic activity, streamflow, and ecological indicators; (2) assessing resources; and (3) providing geospatial information.

-

In addition to its high priority mission responsibilities, the USGS should shift toward the value-added activities of data analysis, problem solving, and information dissemination.

-

The USGS should continue to exercise national leadership in natural hazards research and risk communication.

-

The USGS should provide national leadership in the provision of natural resource information.

This suite of major responsibilities has implications for geography at the USGS in terms of the dominant geographic techniques of cartography, remote sensing, and geographic information systems (GIS). As the Survey becomes more deeply involved in acquiring, processing, and disseminating geospatial data, the skills of geographic specialists will become even more

important. The design and production of maps evolves from a paper exercise to a cartographic design problem familiar to geographers. By suturing remote sensing to GIS, the Survey can apply geographic technical skills and provide products with raw data that have already graduated to the realm of information. The Survey also has the opportunity to contribute meaningful basic research in GIScience (GIS combined with spatial analysis) such as research to develop supporting theory for GIS, physical science for remote sensing, and mathematics for spatial statistics.

To implement the new vision and mission, Director Charles G.Groat charged a Survey Strategic Change Team to outline a managerial mechanism. The team’s objective was to change the Survey from its loose confederation of divisions into a more closely connected community adhering to, accepting, and sharing the same vision and mission. The Strategic Change Team expanded upon the earlier general vision statement (USGS, 1999), stating:

The Strategic Change Team envisions a flexible and responsive USGS that is a recognized leader in providing natural sciences information, knowledge, and tools. Customers, partners, and USGS employees and managers will form an interactive community with a common passion to create, share, and use knowledge of the natural sciences to solve society’s complex problems.

To bring about such a vision the Strategic Change Team recommended a number of adjustments, the most important of which was to alter the organizational structure. Instead of maintaining a divisional perspective (e.g., geology, hydrology, mapping), the team proposed a Survey-centered framework view, which would emphasize multidisciplinary approaches and a regional structure rather than a topical one. Increased emphasis would be placed on management and decisions taken at the regional offices in Reston, Virginia (eastern); Denver, Colorado (central); and Menlo Park, California (western), thereby bringing the Survey closer to its clients and partners.

In response, the USGS eliminated the former division organizational structure (Biological Resources Division, National Mapping Division, Geologic Division, and Water Resources Division) in the fall of 2001 and replaced it with a discipline-based structure: Biology Discipline, Geology Discipline, Geography Discipline, and Water Discipline. Scientific efforts are under the direction of an associate director in each discipline at the national headquarters. The Survey includes associate directors for the Geology Discipline, Geography Discipline, Water Discipline, and Biology Discipline, and regional directors for each Discipline are at each regional office. The elimination of divisional boundaries in the Survey is intended to

ease the formation of interdisciplinary teams and to improve the way complex problems that the Survey’s clients and partners face regularly, are addressed.

Implementation of the reforms proposed by the Strategic Change Team and the development of disciplines have reopened opportunities for geographic contributions at the USGS in two ways. First, geography can provide the mechanism for integrating multidisciplinary studies and, second, the regionalization of the Survey taps the traditional strength of regional geography.

Geographic integration of data, explanations, and predictions is a logical approach for earth, water, and biological resources or hazards. Much of the data collected by governments at all levels has locational identifiers, so the association of geologic, hydrologic, biologic, social, and economic data is easier than ever before. The advent of highly sophisticated GISs, along with desktop versions useable by the non-specialist, further enhance the role of geography as an integrator for multidisciplinary approaches. Thus, geography and geographic data can provide a common language for specialist scientists working on common issues and problems.

Integration in the Survey and in geography elsewhere is often an exercise in regionalization. The regional organization of the USGS not only brings the Survey closer to its clients and partners, but also provides a source of regional specialists for its many clients. These individuals, reminiscent of the regional geographers who once integrated the natural and social sciences by geographic area, are potential facilitators for multidisciplinary investigations and management teams, as well as information contacts for the public. Regional geography can provide the Survey with a method of packaging data for multidisciplinary users outside the agency. The resurgence of regional interests in U.S. academic geography complements this trend toward regionalization within the USGS.

The relationship between geography inside and outside the USGS is a two-way connection. While geography plays a role in the new vision and mission of the USGS, the Survey can also affect the impact and progress of American geography. By providing the field of geography with an entry to federal natural science, the USGS can stimulate the best research, particularly in geospatial information science, natural hazards, and resource analysis. The USGS can become a critical contact point between the natural and social sciences, bringing these two perspectives closer in addressing the nation’s needs. The Survey can connect its natural science data with social and economic data, especially from the Departments of Commerce and Transportation.

THE GEOGRAPHY DISCIPLINE AT THE USGS

The USGS was once divided into divisions related to subject matter, but during its recent reorganization the divisions were replaced with “disciplines.” The Geography Discipline (once the National Mapping Division) has three programs: Cooperative Topographic Mapping, Land Remote Sensing, and Geographic Analysis and Monitoring. The Geography Discipline employs 1274 people, most of whom are technical grade specialists, and 369 contractors. The Geography Discipline’s work force includes 10 Ph.D. geographers. Other disciplines may include a small number of additional geography Ph.D. holders. The number of Ph.D. researchers with degrees in subject matter coincidental with the Geography Discipline is small in comparison with other USGS disciplines. The Geology Discipline includes about 500 Ph.D. geoscientists; the Biology Discipline about 400 Ph.D. bioscientists; and the Water Discipline about 200 Ph.D. hydroscientists. The presence of these substantial numbers of Ph.D. researchers in the other disciplines provide those disciplines with a vital characteristic that the Geography Discipline lacks: a culture characterized by basic research ethics. These ethics include the skill to pose challenging questions, pursue rigorous analysis, and strive for predictions in a thoughtful agenda.

The budget for the Geography Discipline (a congressionally determined line item in the Survey’s budget) has remained relatively level for the past decade, while other disciplines have increased until the most recent budget cycle. For FY2002 the budget was $133.3 million, approximately 15 percent of the total USGS budget. The Cooperative Topographic Mapping program received 61 percent of the Geography Discipline’s total, Land Remote Sensing received 27 percent, and Geographic Analysis and Monitoring received 12 percent.

The combination of a history of emphasis on production, a lack of critical mass of Ph.D. researchers, and a budget that provides very minor support for its research and analysis program has created a Geography Discipline with a weak research element. This shortcoming occurs at a time when the Survey’s vision and mission emphasize geography to a greater degree than at any time in the last century.

STUDY AND REPORT

This study and report constitute part of the reformation of the USGS. In 1999, while the Survey was seeking to refine its self-image, its disciplines of geology, hydrology, biology, and geography also began reviewing themselves and their futures. John Kelmelis, Chief Scientist for Geography, approached

the NRC’s Committee on Geography of the Board on Earth Sciences and Resources and suggested that the USGS could benefit from input by geographers outside the Survey. After the study was requested by the USGS, the NRC formed the Committee on Research Priorities in Geography at the USGS. The committee was invited to conduct a study on research opportunities in geography as they relate to the science goals and responsibilities of the USGS. It was asked to address the societal needs for geographic research and the appropriate federal research role. Specifically, the committee was charged to consider the following areas of concern to the Geography Discipline of the USGS:

-

The role of the USGS in advancing the state of knowledge of the discipline (geography, cartography, and geographic information sciences);

-

The role of the USGS in improving the understanding of the dynamic connections between the land surface and human interactions with it;

-

The role of the USGS in maintaining and enhancing the tools and methods for conducting and applying geographic research; and

-

The role of the USGS in bridging the gap between geographic science, policy making, and management.

In answering this charge the committee has created a report with four dominant themes:

-

The Geography Discipline should engage in scientific research.

-

The geographic research throughout the USGS should provide integrative science for investigations of the Critical Zone.

-

The Geography Discipline should develop partnerships within the Survey and with the field of geography outside the Survey.

-

Geography should develop a long-term core research agenda that includes several projects of the magnitude of the National Map.

As a foundation for geography’s future contributions to knowledge detailed in subsequent chapters, Chapter 2 reviews the history of geography and geographers at the USGS. Chapter 3 outlines priorities for data and information management. Chapter 4 explores priorities for geographic information science (GIScience) as a means of maintaining and enhancing the geographic tools and technology of the Survey. Chapter 5 outlines priorities for research into the interactions between U.S. society and the land surface that supports it. Chapter 6 presents the committee’s conclusions and recommendations.