Executive Summary

This report follows several studies spearheaded by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and other groups that document disturbing shortfalls in the quality of health care in the United States. The following statement prepared for the National Roundtable on Health Care Quality captures the magnitude and scope of the problem:

Serious and widespread quality problems exist throughout American medicine….[They] occur in small and large communities alike, in all parts of the country and with approximately equal frequency in managed care and fee-for-service systems of care. Very large numbers of Americans are harmed as a result (Chassin and Galvin, 1998:1000).

Likewise, two subsequent IOM studies—To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Institute of Medicine, 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21stCentury (Institute of Medicine, 2001a)—focus national attention on patient safety concerns surrounding the high incidence of medical errors and sizable gaps in health care quality, respectively.

In addition to the IOM, many others have assumed leadership roles in the movement to address and improve health care safety and quality. These efforts have included both large-scale national initiatives, such as the President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry (1998) and Healthy People 2010 (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000), and private efforts such as the work of the RAND Corporation, which resulted in a call for mandatory tracking and reporting of health care quality (Schuster et al., 1998). The newly released chart book from the Commonwealth Fund, which examines the current status of

quality of health care in the United States, confirms that quality problems persist (Leatherman and McCarthy, 2002):

-

Fewer than half of adults aged 50 and over were found to have received recommended screening tests for colorectal cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001; Leatherman and McCarthy, 2002).

-

Inadequate care after a heart attack results in 18,000 unnecessary deaths per year (Chassin, 1997).

-

In a recent survey, 17 million people reported being told by their pharmacist that the drugs they were prescribed could cause an interaction (Harris Interactive, 2001).

Problems such as those cited above have now been noted so frequently that we risk becoming desensitized even as we pursue change. Our technical lexicon of performance improvements and system interventions can obscure the stark reality that we invest billions in research to find appropriate treatments (National Institutes of Health, 2002), we spend more than $1 trillion on health care annually (Heffler et al., 2002), we have extraordinary knowledge and capacity to deliver the best care in the world, but we repeatedly fail to translate that knowledge and capacity into clinical practice.

Study Purpose and Scope

The IOM’s Quality Chasm report sets forth a bold strategy for achieving substantial improvement in health care quality during the coming decade (Institute of Medicine, 2001a). As a crucial first step in making the nation’s health care system more responsive to the needs of patients and more capable of delivering science-based care, the Quality Chasm report recommends the systematic identification of priority areas for quality improvement. The idea behind this strategy was to have various groups at different levels focus on improving care in a limited set of priority areas, with the hope that their collective efforts would help move the nation forward toward achieving better-quality health care for all Americans. In response, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) contracted with the IOM to form a committee whose charge was threefold: to select criteria for screening potential priority areas, to develop a process for applying those criteria, and to generate a list of approximately 15 to 20 candidate areas.

Guiding Principles

Systems Approach

Behind each of the priority areas recommended in this report is a patient who may be receiving poor quality care. This is due not to a lack of effective treatments, but to inadequate health care delivery systems that fail to implement these treatments. For this reason, the committee considered quality to be a systems property, recognizing that although the health care workforce is trying hard to deliver the best care, those efforts are doomed to failure with today’s outmoded and poorly designed systems. The committee did not concentrate on ways of improving the efficacy of existing best-practice treatments through either biomedical research or technological innovation, but rather on ways to improve the delivery of those treatments. Indeed the goal of the study was to identify priority areas that presented the greatest opportunity to narrow the gap between what the health care system is routinely doing now and what we know to be best medical practice.

Scope and Framework

The Quality Chasm report proposes that chronic conditions serve as the focal point for the priority areas, given that a limited number of chronic conditions account for the majority of the nation’s health care burden and resource use (Hoffman et al., 1996; Institute of Medicine, 2001a; Partnership for Solutions, 2001; The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2001). Chronic conditions do represent a substantial number of the priority areas on the final list presented in this report; however, this

committee was constituted and charged to go beyond a disease-based approach. Therefore, the committee decided to recommend priority areas that would be representative of the entire spectrum of health care, rather than being limited to one important segment.

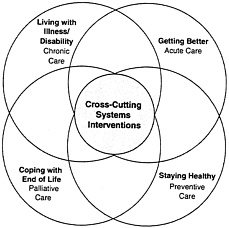

Given this broader perspective, the committee decided a framework would be useful in helping to identify potential candidates for the priority areas. The committee built upon the framework originally developed by the Foundation for Accountability and subsequently incorporated into the National Health Care Quality Report (Foundation for Accountability, 1997a, 1997b; Institute of Medicine, 2001b). This consumer-oriented framework encompasses four domains of care: staying healthy (preventive care), getting better (acute care), living with illness/disability (chronic care), and coping with end of life (palliative care).1 In response to the Quality Chasm report’s ardent appeal for systems change, the committee supplemented these four categories with a fifth—cross-cutting systems interventions—to address vitally important areas, such as coordination of care, that cut across specific conditions and domains.

Like all frameworks, that employed by the committee has advantages as well as limitations. The committee found its framework to be useful for initially identifying candidate areas and then later in the process for checking the balance of the final portfolio of recommended priority areas. However, one of the framework’s limitations was that it tended to result in placing conditions into rigid categories, whereas health care for many of the priority areas involves services in all five categories. Figure ES-1 presents the committee’s initial framework for determining priority areas. The overlapping circles represent the interrelatedness of the five categories.

Recommendation 1: The committee recommends that the priority areas collectively:

-

Represent the U.S. population’s health care needs across the lifespan, in multiple health care settings involving many types of health care professionals.

-

Extend across the full spectrum of health care, from keeping people well and maximizing overall health; to providing treatment to cure people of disease and health problems as often as possible; to assisting people who become chronically ill to live longer, more productive and comfortable lives; to providing dignified care at the end of life that is respectful of the values and preferences of individuals and their families.

FIGURE ES-1 The committee’s initial framework for determining priority areas.

Evidence-Based Approach

The committee developed its recommendations using an evidence-based approach. Particularly for estimates of disease burden, the committee relied on quantitative data from national datasets to compare the burden of disease as regards prevalence, disability, and costs across priority areas.

At the same time, the committee recognized that the existing evidence base could provide only partial guidance for fulfilling its charge. Specifically, there was little quantitative data available for comparing the costs and outcomes of quality improvement programs across different priority areas. For this purpose, the committee supplemented quantitative data with qualitative data and case studies of successful examples of system change. These sources were used to study whether, for a condition posing a high health burden, there was evidence that quality improvement could substantially improve care. Here, the committee used evidence to examine the potential benefits of system change, rather than to generate numerical rankings for particular priority areas. To ensure a stronger evidence base in the future, the committee has recommended strategic investment in research on effective interventions that can improve the quality of care in a number of the priority areas and the development of accompanying standardized measures.

Criteria

The committee used three closely related criteria—impact, improvability, and inclusiveness—in selecting the priority areas.

Recommendation 2: The committee recommends use of the following criteria for identifying priority areas:

-

Impact —the extent of the burden— disability, mortality, and economic costs—imposed by a condition, including effects on patients, families, communities, and societies.

-

Improvability —the extent of the gap between current practice and evidence-based best practice and the likelihood that the gap can be closed and conditions improved through change in an area; and the opportunity to achieve dramatic improvements in the six national quality aims identified in the Quality Chasm report (safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency and equity).

-

Inclusiveness—the relevance of an area to a broad range of individuals with regard to age, gender, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity/ race (equity); the generalizability of associated quality improvement strategies to many types of conditions and illnesses across the spectrum of health care (representativeness); and the breadth of change effected through such strategies across a range of health care settings and providers (reach).

Final List of Priority Areas

The committee’s selection process yielded a final set of 20 priority areas for improvement in health care quality. Improving the delivery of care in any of these areas would enable stakeholders at the national, state, and local levels to begin setting a course for quality health care while addressing unacceptable disparities in care for all Americans. The committee made no attempt to rank order the priority areas selected. The first 2 listed—care coordination and self-management/health literacy—are cross-cutting areas in which improvements would benefit a broad array of patients. The 17 that follow represent the continuum of care across the life span and are relevant to preventive care, inpatient/surgical care, chronic conditions, end-of-life care, and behavioral health, as well as to care for children and adolescents (see boxes ES-1 to ES-6). Finally, obesity is included as an “emerging area”2 that does not at this point satisfy the selection criteria as fully as the other 19 priority areas.

Recommendation 3: The committee recommends that DHHS, along with other public and private entities, focus on the following priority areas for transforming health care:

-

Care coordination (cross-cutting)

-

Self-management/health literacy (cross-cutting)

-

Asthma—appropriate treatment for persons with mild/moderate persistent asthma

-

Cancer screening that is evidence- based—focus on colorectal and cervical cancer

-

Children with special health care needs 3

-

Diabetes—focus on appropriate management of early disease

-

End of life with advanced organ system failure—focus on congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

Frailty associated with old age— preventing falls and pressure ulcers, maximizing function, and developing advanced care plans

-

Hypertension—focus on appropriate management of early disease

-

Immunization—children and adults

-

Ischemic heart disease—prevention, reduction of recurring events, and optimization of functional capacity

-

Major depression—screening and treatment

-

Medication management— preventing medication errors and overuse of antibiotics

-

Nosocomial infections—prevention and surveillance

-

Pain control in advanced cancer

-

Pregnancy and childbirth— appropriate prenatal and intrapartum care

-

Severe and persistent mental illness—focus on treatment in the public sector

-

Stroke—early intervention and rehabilitation

-

Tobacco dependence treatment in adults

-

Obesity (emerging area)

|

2 |

An emerging area is one of high burden (impact) that affects a broad range of individuals (inclusiveness) and for which the evidence base for effective interventions (improvability) is still forming. |

|

3 |

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau defines this population as “those (children) who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally” (McPherson et al., 1998:138). |

|

Box ES-1 Priority Areas That Relate to Preventive Care

|

|

Box ES-2 Priority Areas That Relate to Behavioral Health

|

|

Box ES-3 Priority Areas That Relate to Chronic Conditions

|

|

Box ES-4 Priority Areas That Relate to End of Life

|

|

Box ES-5 Priority Areas That Relate to Children and Adolescents

|

|

Box ES-6 Priority Areas That Relate to Inpatient/Surgical Care

|

Process for Identifying Priority Areas

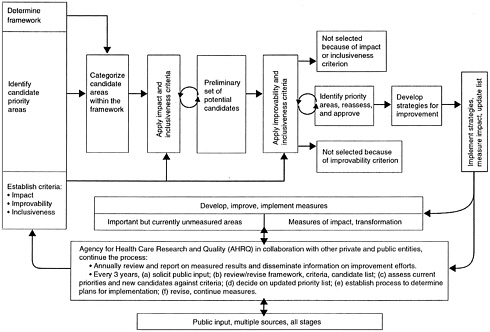

In response to its charge, the committee developed a process for determining priority areas (see Figure ES-2). This process was refined according to the committee’s experience in selecting the priority areas recommended in this report, and is suggested as a model for future priority-setting efforts. The steps in the process can be summarized as follows:

-

Determine a framework for the priority areas.

-

Identify candidate areas.

-

Establish criteria for selecting the final priority areas.

-

Categorize candidate areas within the framework.

-

Apply impact and inclusiveness criteria to the candidates.

-

Apply criteria of improvability and inclusiveness to the preliminary set of areas obtained in step 5.

-

Identify priority areas; reassess and approve.

-

Implement strategies for improving care in the priority areas, measure the impact of implementation, and review/update the list of areas.

Throughout the process, public input should be solicited from multiple sources.

Following is a detailed description of each of the above steps. This description encompasses both the process initially formulated by the committee and modifications that emerged as a result of the committee’s deliberations.

Determine Framework

The framework used by the committee’s was discussed above and is detailed in Chapter 1.

Identify Candidates

In developing an initial candidate list, the committee drew on a variety of sources. These included the collective knowledge and broad expertise of its members (see Appendix A for biographical sketches of committee members), feedback received from presenters and the public at a workshop held in May 2002 (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda), and work done by other groups in the area of the burden of chronic conditions/diseases and by organizations that have already established lists of priority conditions/areas to meet their specific needs. Using all these resources, the committee settled on a list of approximately 60 candidate priority areas to screen by means of the process outlined above. Selecting just 60 candidates for the first cut was extremely difficult, as there are hundreds of diseases, preventive services, and health care system failures that might be included. The remaining steps in the process were then applied to narrow this list still further to the 20 areas recommended by the committee.

Establish Criteria

The criteria used by the committee were cited above and are discussed in depth in Chapter 2.

Categorize Candidates Within the Framework

Once a pool of candidate areas had been established, they were organized within the categories of the framework. For example, using the committee’s initial framework, diabetes was placed under chronic care, tobacco dependency treatment under preventive care, pain control under palliative care, antibiotic overuse under acute care, and care coordination under cross-cutting systems interventions.

Apply Criteria to Candidates

After identifying a list of candidate priority areas and organizing them within the framework, the committee applied the selection criteria to each area, being particularly sensitive to the impact on disadvantaged populations. All three criteria were applied in a single step when the committee performed this selection process. On the basis of its experience, however, the committee recommends a two-step process for future efforts: one should screen for impact first, then for improvability, and throughout the process, particular attention should be paid to inclusiveness. This two-step approach would identify more clearly for consumers, practitioners, and researchers the rationale for including some areas and not others. It would elucidate, for example, which areas did not meet the impact criterion and which met this criterion but not that of improvability. Such clarification could help shape future work in the areas involved. Moreover, future applications of this approach to update the priority areas might well involve richer data analysis and more extensive feedback from the public and health professionals.

Identify Priority Areas

The priority areas selected by the committee were listed earlier under recommendation 3 and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Next Steps

With the priority areas having been identified, the final step in the process is to implement strategies for improving care in the priority areas, measure the impact of implementation, and periodically review/update the list of areas. Impact should be measured using methods that are standardized and can permit comparison across these diverse areas of quality improvement. The assessment must include measures of the degree to which the system has been transformed and of the clinical impact on patient care. As such changes are effected, the list of priority areas should be reviewed and updated—optimally every 3 to 5 years. Other areas may need to be added to the list as the result of new data on impact or the development of new treatment interventions. Likewise, if strategies for improvement are effective, it may be possible to remove some areas from the list.

Recommendation 4: The committee recommends that the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), in collaboration with other private and public organizations, be responsible for continuous assessment of progress and updating of the list of priority areas. These responsibilities should include:

-

Developing and improving data collection and measurement systems for assessing the effectiveness of quality improvement efforts.

-

Supporting the development and dissemination of valid, accurate, and reliable standardized measures of quality.

-

Measuring key attributes and outcomes and making this information available to the public.

-

Revising the selection criteria and the list of priority areas.

-

Reviewing the evidence base and results, and deciding on updated priorities every 3 to 5 years.

-

Assessing changes in the attributes of society that affect health and health care and could alter the priority of various areas.

-

Disseminating the results of strategies for quality improvement in the priority areas.

Throughout this study, the committee often encountered a lack of reliable measures to use in assessing improvability for the priority areas under consideration. Available datasets, although useful, were also limited in that they were unable to provide information on health status and health functioning because of their

disease—and procedure-based orientation. In addition, it was difficult to compare many quality improvement efforts because of a lack of standardization in the way outcomes were measured. Thus, the committee concluded that particular attention should be focused on enhancing survey data and developing new strategies for collecting, collating, and disseminating quality improvement data. Those conducting quality improvement studies should be encouraged to include a core set of measures that would allow comparability across different conditions, just as consensus standards have been developed for conducting and reporting cost-effectiveness analyses (Gold, 1996; Russell et al., 1996; Siegel et al., 1996; Weinstein et al., 1996). Only with such standardized approaches will it be possible to use findings from quality improvement studies for future efforts at priority setting.

Recommendation 5: The committee recommends that data collection in the priority areas:

-

Go beyond the usual reliance on disease—and procedure-based information to include data on the health and functioning of the U.S. population.

-

Cover relevant demographic and regional groups, as well as the population as a whole, with particular emphasis on identifying disparities in care.

-

Be consistent within and across categories to ensure accurate assessment and comparison of quality enhancement efforts.

If AHRQ is to spearhead this undertaking, appropriate funds must be allocated for the purpose. National experts should be convened to develop action plans in the priority areas, and this should be done expeditiously so as to sustain momentum and ensure the timeliness of the committee’s recommendations.

Recommendation 6: The committee recommends that the Congress and the Administration provide the necessary support for the ongoing process of monitoring progress in the priority areas and updating the list of areas. This support should encompass:

-

The administrative costs borne by AHRQ.

-

The costs of developing and implementing data collection mechanisms and improving the capacity to measure results.

-

The costs of investing strategically in research aimed at developing new scientific evidence on interventions that improve the quality of care and at creating additional accurate, valid, and reliable standardized measures of quality. Such research is especially critical in areas of high importance in which either the scientific evidence for effective interventions is lacking, or current measures of quality are inadequate.

The list of priority areas identified by the committee is intended to serve as a starting point for transforming the nation’s health care system. Many of the leading causes of death are on this list. Just five of the conditions included—heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes— account for approximately 1.5 million deaths annually and represent 63 percent of total deaths in the United States (Minino and Smith, 2001).4 If redesigning systems of care resulted in merely a 5 percent mortality improvement in these areas alone, nearly 75,000 premature deaths could potentially be averted.

Although AHRQ’s role in monitoring progress and updating the list of areas will be

|

4 |

Heart disease (ischemic heart disease and hypertension), 537,088; cancer, 551,833; stroke, 166,028; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 123,550; diabetes, 68,662. Total=1,447,161; total deaths all causes=2,404,598. |

critical, the health care system will be changed only through the individual and organized actions of patients, families, doctors, nurses, other health professionals, and administrators; no national body or collaboration can accomplish the task alone. The priority areas deliberately encompass a wide range of health care issues in which improvement is needed for overall system change. However, the priorities are also specific enough that individuals and organizations can choose areas on which to focus their improvement efforts, helping to guarantee that all Americans will receive the quality health care they deserve.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. Trends in screening for colorectal cancer— United States, 1997 and 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report50:161–66.

Chassin, M.R.1997. Assessing strategies for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood)16

Chassin, M.R., and R.W.Galvin. 1998. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality . JAMA280 (11): 1000–5.

Foundation for Accountability. 1997a. “The FACCT Consumer Information Framework: Comparative Information for Better Health Care Decisions.” Online. Available at http://www.facct.org/information.html [accessed June 4, 2002].

——. 1997b. Reporting Quality Information to Consumers.Portland, OR: FACCT.

Gold, M.R.1996. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine.New York: Oxford University Press.

Harris Interactive. 2001. Survey on Chronic Illness and Caregiving.New York: Harris Interactive.

Heffler, S., S.Smith, G.Won, M.K.Clemens, S.Keehan, and M.Zezza. 2002. Health spending projections for 2001–2011: The latest outlook. Faster health spending growth and a slowing economy drive the health spending projection for 2001 up sharply. Health Aff (Millwood)21 (2):207–18.

Hoffman, C., D.Rice, and H.Y.Sung. 1996. Persons with chronic conditions: Their prevalence and costs. JAMA276 (18):1473–9.

Institute of Medicine. 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.L.T.Kohn, J.M.Corrigan, and M.S.Donaldson, eds. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press.

——. 2001a. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

——. 2001b. Envisioning the National Health Care Quality Report.M.P.Hurtado, E.K. Swift, and J.M.Corrigan, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Leatherman, S. and D.McCarthy. 2002. Quality of Health Care in the United States: A Chartbook. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund.

McPherson, M., P.Arango, H.Fox, C.Lauver, M.McManus, P.W.Newacheck, J.M.Perrin, J.P.Shonkoff, and B.Strickland. 1998. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics102 (1 Pt 1): 137–40.

Minino, A.M. and B.L.Smith. 2001. National Vital Statistics Reports.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Institutes of Health. 2002. “NIH Press Release for the FY 2003 President’s Budget.” Online. Available at www.nih.gov/news/budgetfy2003/2003NIHpresbudget.htm [accessed Aug. 8, 2002].

Partnership for Solutions, The Johns Hopkins University. 2001. “Partnership for Solutions: A National Program of The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.” Online. Available at http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/statistics/prevalence.htm [accessed Dec. 12, 2002].

President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry. 1998. Quality First: Better Health Care for All Americans—Final Report to the President of the United States.Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Russell, L.B., M.R.Gold, J.E.Siegel, N.Daniels, and M.C.Weinstein. 1996. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA276 (14): 1172–7.

Schuster, M.A., E.A.McGlynn, and R.H.Brook. 1998. How good is the quality of health care in the United States?Milbank Q76 (4):517–63, 509.

Siegel, J.E., M.C.Weinstein, L.B.Russell, and M.R.Gold. 1996. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA276 (16):1339–41.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2001. A Portrait of the Chronically Ill in America. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health.2nd edition. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Weinstein, M.C., J.E.Siegel, M.R.Gold, M.S.Kamlet, and L.B.Russell. 1996. Recommendations of the Panel on Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 276 (15):1253–8.