Chapter 3

Priority Areas for Quality Improvement

The committee’s deliberations led to the selection of 20 priority areas for health care quality improvement:

-

Care coordination (cross-cutting)

-

Self-management/health literacy (cross-cutting)

-

Asthma—appropriate treatment for persons with mild/moderate persistent asthma

-

Cancer screening that is evidence-based—focus on colorectal and cervical cancer.

-

Children with special health care needs1

-

Diabetes—focus on appropriate management of early disease

-

End of life with advanced organ system failure—focus on congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

-

Frailty associated with old age—preventing falls and pressure ulcers, maximizing function, and developing advanced care plans

-

Hypertension—focus on appropriate management of early disease

-

Immunization—children and adults

-

Ischemic heart disease—prevention, reduction of recurring events, and optimization of functional capacity

-

Major depression—screening and treatment

-

Medication management—preventing medication errors and overuse of antibiotics

-

Nosocomial infections—prevention and surveillance

-

Pain control in advanced cancer

-

Pregnancy and childbirth—appropriate prenatal and intrapartum care

-

Severe and persistent mental illness—focus on treatment in the public sector

-

Stroke—early intervention and rehabilitation

-

Tobacco dependence treatment in adults

-

Obesity (emerging area)2

The committee made no attempt to rank order the priority areas selected. The first 2 listed above—care coordination and self-management/health literacy—are cross-cutting areas in which improvements would benefit a broad array of patients. The 17 that follow represent the continuum of care across the life span and are relevant to preventive care, inpatient/surgical care, chronic conditions, end-of-life care, and behavioral health, as well as to care for children and adolescents. Finally, obesity is included as an “emerging area” that does not at this point satisfy the selection criteria as fully as the other 19 priority areas.

This chapter first reviews the breadth of opportunities for health care improvement represented by the committee’s recommended list of priority areas. The three types of areas included on the list—cross-cutting areas, specific conditions, and emerging areas—are then described. The chapter next profiles each area in detail, including the aim of intervention in that area and the rationale for the area’s selection in light of the three criteria discussed in Chapter 2—impact, improvability and inclusiveness.

Breadth of Opportunities Represented by Priority Areas

The priority areas selected by the committee can be viewed through a variety of lenses. They represent a range of health care services and challenges, including:

-

The full spectrum of health care, from preventive and acute care, to chronic disease management, to long-term and palliative care at the end of life. Thus they encompass a wide variety of health care services, spanning both reactive acute, emergency, and surgical care and the proactive planned care required to prevent and manage chronic disease, pain, and disability.

-

Care provided for a variety of populations representing Americans of all ages and demographic groups, including care that is oriented to individuals and families, as well as populations.

-

Care delivered in a range of publicly and privately financed ambulatory and inpatient health care settings (outpatient and community health centers, home-based care, emergency departments, hospitals, and nursing homes) by a variety of health care practitioners (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals), including both generalists and specialists.

The Full Spectrum of Health Care

As noted, the priority areas recommended by the committee represent health care quality improvement challenges and opportunities across the full spectrum of health care. In fact, having relevance to multiple domains of care strengthened an area’s chances of being included on the final list. Boxes 3–1 to 3–6 show how the priority areas relate to a wide range of health care needs. For example, ischemic heart disease figures prominently in preventive care, inpatient/surgical care, chronic

care, and end-of-life care. Similarly, medication management cuts across inpatient/ surgical care, chronic care, end-of-life care, and child/adolescent care. Obesity—the emerging area—touches on preventive care, chronic care, behavioral health, and child/adolescent care.

The Entire Life Span

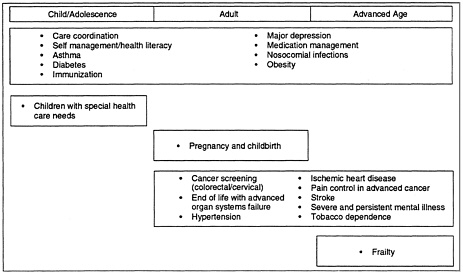

The committee made a concerted effort to ensure that the priority areas selected would represent issues pertinent to all age groups. Figure 3–1 shows how the priority areas cut across the stages of a typical life span. As demonstrated, only a few areas are unique to certain age groups, such as children with special health care needs and frailty prevention and management. Many areas, such as cancer screening and hypertension, cluster around adulthood and extend into end of life. Additionally, nine of the priority areas encompass the entire life span.

Figure 3–1: Priority areas across the life span.

Diverse Health Care Settings and Professions

The set of priority areas recommended by the committee involves care that is provided in multiple health care settings and organizations, care that is both privately and publicly funded, and care that is provided by a variety of health care professionals. For example, effective asthma management requires integration of care among primary care providers, pediatricians, schools, hospitals (particularly emergency rooms), and pharmacists. Adequate pain control in advanced cancer and stroke rehabilitation require a continuum of care that includes home, community, clinic, and hospital. Improving quality of care for severe and persistent mental illness, such as psychosis, provides an opportunity to focus on the effectiveness of mental health services provided by the public sector (Narrow et al., 2000; Wells, 2002a). To close the gaps between best practice and usual care for the full set of proposed areas will require the collective expertise of a vast array of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals, social workers, and vested laypersons. Virtually every conventional medical specialty will need to develop strategies for one or more of these priority areas.

|

Box 3–1 Priority Areas That Relate to Preventive Care

|

|

Box 3–2 Priority Areas That Relate to Behavioral Health

|

|

Box 3–3 Priority Areas That Relate to Chronic Conditions

|

|

Box 3–4 Priority Areas That Relate to End of Life

|

|

Box 3–5 Priority Areas That Relate to Children and Adolescents

|

|

Box 3–6 Priority Areas That Relate to Inpatient/Surgical Care

|

Three Types of Priority Areas

Cross-Cutting Areas

There was strong consensus among the committee members on the critical need to improve care coordination, support for self-management, and health literacy for all patients and their families. System and policy changes to achieve improvement in these cross-cutting priority areas would involve most health care organizations and practitioners, could impact all types of conditions, and could provide a means of dramatically improving health care for all Americans.

Improved care coordination would, if applied broadly, have an especially important impact on improving health care processes and outcomes for children and adults with serious chronic illness and multiple chronic conditions (Anderson and Knickman, 2001; Anderson, 2002b). Efforts to improve health literacy are in turn essential for effective self-management and collaborative care. For example, a recent study found that diabetics with poor health literacy, unable to read and/or comprehend directions on their pill bottles, had worse blood sugar control and higher rates of preventable vision impairment (Schillinger et al., 2002). Devising strategies to improve health literacy—both at the micro level, where patients and health care professionals interact, and at the macro level, where population health is the target—would not only improve diabetes outcomes, but also form part of a package of improvements for nearly all inadequate aspects of health care.

Specific Priority Conditions

Chronic Care

In keeping with the Quality Chasm report, which notes the critical need to close quality gaps for the growing numbers of Americans with chronic disease (Institute of Medicine, 2001a), the majority of the specific priority conditions recommended are chronic. For all of the recommended conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease, there are known, effective interventions that can be applied to improve health outcomes, reduce disease burden, and prevent more serious health problems later in life. Moreover, the enormous and rapid growth in the prevalence and burden of chronic disease over the past two decades has been a major force in clarifying the limitations of the current health care system—which evolved primarily to meet acute and emergency health care needs—thus motivating broad action for health care system redesign (Bodenheimer et al., 2002; Institute of Medicine, 2001a).

Acute Care

One priority area within the realm of acute care—effective medication management— focuses on preventing medication errors and the overprescribing of antibiotics, particularly for acute respiratory infections in children. This area provides an excellent opportunity for designing interventions that can enhance the use and capacity of management information systems. For example, lecturing to physicians about medical errors yields small gains, but technological advances, such as the electronic medical record tied to computerized medication orders with acceptable dosage ranges and interactions, can dramatically reduce errors arising from incorrect orders (Bates et al., 1999; Kaushal et al., 2001). Computerized alerts of potential drug interactions, prompts and reminders for required services, and electronic physician order entry for prescriptions could all be put in place to safeguard health and improve quality of care (Hunt et al., 1998). Corrective measures that redesign work so that errors are “engineered out” are repeatedly found to have high leverage.

Preventive Care

The committee explicitly included preventive services among the domains of health care that should be represented by the priority areas. Doing so reflected a growing body of evidence that early detection and timely

intervention for risk factors or diseases in their preclinical stages are effective in reducing both disease burden and costs. Selected priority areas represent a range of clinical preventive services involving immunization, screening, and counseling for lifestyle changes, which would singly and collectively reduce morbidity and mortality due to the nation’s leading chronic illnesses and infectious disease threats. Specifically, childhood/adult immunization, improved screening for colorectal and cervical cancers, and brief primary care interventions for adult tobacco dependence have been identified as major opportunities for cost-effective improvements in the nation’s health care system (Coffield et al., 2001).

For example, just 3–5 minutes of counseling and medication advice given to adult smokers by their physician could more than double the quitting success rates smokers achieve on their own (Fiore et al., 2000). Since there are over 430,000 tobacco-related deaths each year from heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, and chronic lung disease among U.S. adults, the impact of this simple intervention, combined with other effective modes of tobacco treatment, would be dramatic (Max, 2001; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

Unfortunately, only about 50 percent of patients who smoke receive such advice and assistance, largely because supports such as office-based reminder systems and insurance coverage for smoking cessation services are not widely in place (Goodwin et al., 2001; Thorndike et al., 1998). Treating tobacco dependence is critical to preventing disease in healthy populations of smokers, the progression of illnesses caused by tobacco use, poor pregnancy outcomes associated with smoking, and pediatric asthma in infants and adolescents whose parents smoke. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that the types of system and policy changes needed to spur broader use of evidence-based tobacco interventions are similar to those required to support the wider delivery of other proven interventions for changes in health behavior in primary care, such as counseling on physical activity and diet and on the importance of reducing risky consumption of alcohol (Glasgow et al., 2001).

Palliative Care

Between 2010 and 2030, America’s baby boomers will move beyond the age of 65 and swell the number of older persons to approximately 70 million, representing 20 percent of the population (Administration on Aging, 2002). Accordingly, the committee placed particular emphasis on addressing the complex care issues that surface after age 65 and particularly after age 80. One of the priority areas in the category of palliative care is frailty. Nearly everyone who survives past age 80 experiences a period of frailty involving decreased functional status as a result of multiple health problems, such as heart and lung disease, as well as cognitive deficits resulting from dementia or stroke. As more and more Americans face the physical and social challenges of frailty, systems of care must adapt in ways that allow them to live comfortably and safely at home. Advanced care plans should be put in place that are respectful of both the patient’s and family’s wishes. This priority area can serve as an exemplar for health care quality improvements that incorporate changes at various levels of the health care delivery system to provide integrated, dignified care for those of advanced age.

Emerging Areas

Obesity was intentionally placed last on the committee’s list and classified as an “emerging area.” The prevalence of overweight and obesity among Americans has reached epidemic proportions (Mokdad et al., 2001; Yanovski and Yanovski, 2002). Obesity represents an important medical condition in its own right and contributes to morbidity and mortality for other diseases, including heart disease, type II diabetes, osteoarthritis, hypertension, and cancer. Addressing growing rates of obesity and obesity-related disease in children and adults has been identified as an urgent national health care priority (Squires, 2001).

Obesity was selected as a priority area based on strong evidence for its impact and inclusiveness, but still emerging evidence for improvability. That is, there was relatively limited evidence for the efficacy of existing best-practice treatments for obesity in children and adults, such as behavioral counseling and drug and surgical interventions (Epstein et al., 2001). In addition, effective treatment for obesity will need to integrate many other aspects of society, such as housing, exercise opportunities, food supply, and work patterns, often considered outside the traditional realm of health care.

The committee’s aim in denoting obesity as “emerging” was to accelerate the rate at which research generates the evidence needed to identify effective interventions and to develop evidence-based treatment guidelines and valid performance measures. Since this area would serve as a model for potential future emerging priority areas, formal reviews of progress on obesity would be conducted more frequently than for other priority areas, perhaps as often as yearly, to determine future directions.

Priority Areas: Detailed Descriptions

The following brief descriptions are intended as illustrative rather than exhaustive profiles for each of the 20 recommended priority areas. The committee’s goal was to provide a starting point for experts in the field to undertake effective national health care quality improvement efforts over the next 3 to 5 years. Each priority area is discussed with reference to the committee’s three selection criteria—impact, improvability, and inclusiveness. A vignette is also provided for selected areas to illustrate how a transformed health care system would provide quality care in that area.

Care Coordination

Aim

To establish and support a continuous healing relationship, enabled by an integrated clinical environment and characterized by the proactive delivery of evidence-based care and follow-up. Clinical integration is further defined as “the extent to which patient care services are coordinated across people, functions, activities, and sites over time so as to maximize the value of services delivered to patients” (Shortell et al., 2000:129).

Rationale for Selection

Impact

Nearly half of the population—125 million Americans—lives with some type of chronic condition. About 60 million live with multiple such conditions. And more than 3 million—2.5 million women and 750,000 men—live with

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Gerard Anderson, Ph.D. (2002).

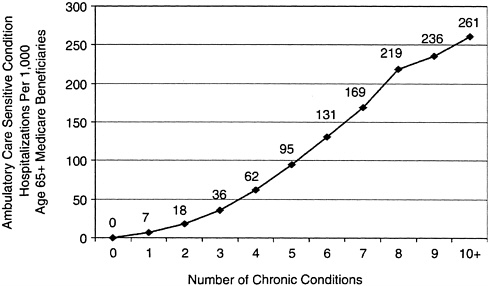

Figure 3–2. Hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions.

five such conditions (Partnership for Solutions, 2001). For those afflicted by one or more chronic conditions, coordination of care over time and across multiple health care providers and settings is crucial. Yet in a survey of over 1,200 physicians conducted in 2001, two-thirds of respondents reported that their training was not adequate to coordinate care or education for patients with chronic conditions (Partnership for Solutions, 2001).

More than 50 percent of patients with hypertension (Joint National Committee on Prevention, 1997), diabetes (Clark et al., 2000), tobacco addition (Perez-Stable and Fuentes-Afflick, 1998), hyperlipidemia (McBride et al., 1998), congestive heart failure (Ni et al., 1998), chronic atrial fibrillation (Samsa et al., 2000), asthma (Legorreta et al., 2000), and depression (Young et al., 2001) are currently managed inadequately. Among the Medicare-eligible population, the average beneficiary sees 6.4 different physicians in a year, 4.6 of those being in the outpatient setting (Anderson, 2002a).

Among this same population, as the number of chronic conditions a person has increases, so, too, does the number of hospitalizations that are inappropriate or avoidable because outpatient treatment would have been effective: from 7 per 1,000 for those with one chronic condition to 95 per 1,000 for those with five chronic conditions and 261 per 1,000 for those with ten or more such conditions (Anderson, 2002a). See Figure 3–2.

Improvability

In a randomized controlled trial of 970 patients with diabetes cared for by over 450 primary care providers, usual care was compared with a program utilizing regular follow-up, decision support, reminder systems, and modern self-management support. After 6 years, patients in the intervention group had significantly better outcomes, including lower HbAlc, blood pressure, and cholesterol levels (Olivarius et al., 2001). A recent review of ambulatory-care diabetic management programs found that patient education and an expanded role for a nurse in the intervention strategy also improved patient outcomes (Renders et al., 2001).

According to a meta-analysis of adult immunization and cancer screening programs, interventions that had the largest impact involved organizational changes, such as the use of a planned care visit for prevention, and designation of nonphysician staff to carry out specific prevention activities (Stone et al., 2002). There is also a growing body of evidence that planned (e.g., proactive, structured) care at set intervals makes a difference, and can be accomplished using nonstandard models, such as group visits (Beck et al., 1997; Sadur et al., 1999).

The Chronic Care Model, described in Chapter 1, provides a structure for planned, clinically integrated care. There are promising indications that a wide variety of health systems can reorganize themselves to deliver such care (The National Coalition on Health Care and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2002; Wagner et al., 2001a).

Inclusiveness

The Institute of Medicine’s 2002 report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care documents racial and ethnic disparities in several of the priority areas recommended in this report, all of which could benefit from a more integrated approach to care. These areas include children with special health care needs, diabetes, end of life with advanced organ system failure, frailty, pregnancy and childbirth, and severe and persistent mental illness (Institute of Medicine, 2002).

|

Box 3–7 Care Coordination One participating organization, Care Management Group of Greater NY, Inc. (CMGNY), in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s National Program on Improving Chronic Illness Care incorporated the elements of the Chronic Care Model to enhance recognition and treatment of depression in patients with congestive heart failure. This collaborative is an excellent example of how effective care coordination, or clinical integration of services, improved health outcomes for the chronically ill, particularly for patients with multiple chronic conditions. First, there was strong organizational support from key leaders at CMGNY, a subsidiary of the North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System. Second, clinical information systems were used to extract claims data and a disease registry was built to identify patients within the plan who had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure (CHF). Physicians participating in the program were given the names of their CHF patients for systematic screening for depression. Patients with recent hospitalizations, patients identified through care management, and patients whose annual costs exceeded $50,000 per year, were all targeted for depression assessment as well. Third, decision support was provided at many levels. Physicians within the plan were invited to attend “managed care college” where they were trained to recognize the classic signs of depression and coached to administer the Patient Health Questionnaire (PAQ), a screening tool for depression. Notably, clinicians were given financial incentives for incorporating the PAQ into their daily practice. Additionally, primary care physicians had access to a psychiatrist by telephone for consultation regarding medication dosage and depression management. Fourth, a nurse practitioner used telephone self-management support techniques to facilitate partnerships between patients and their providers. The hallmark of this relationship was active listening and empathy with the overarching goal to educate the patient about their condition and to monitor and encourage adherence to their treatment plan, including medications and appointments. In addition, goal-setting strategies were developed with the patient to encourage exercise and engagement in pleasant events as well as to resolve treatment-emergent problems such as side effects from antidepressant medications, attitudinal issues and social barriers. Fifth, the overall delivery of care was redesigned to incorporate elements of the chronic illness care model, including care management, decision support and development of community relationships. This included providing services outside the doctor’s office such as home health evaluations, home psychiatric evaluations, physical therapy and a home health aide. A nurse practitioner figured prominently in coordinating, monitoring and following-up of care. Lastly, patients were linked with community resources both on the local and national level. Outcomes from this study were dramatic. After 6 months a 50 percent or greater improvement in depression severity was observed among participants. In the words of one patient with CHF who was clinically depressed and on 20 medications “you have turned my life around” (Cole et al., 2002; Cole, 2002). |

Self-Management/Health Literacy

Aim

To ensure that the sharing of knowledge between clinicians and patients and their families is maximized, that the patient is recognized as the source of control, and that the tools and system supports that make self-management tenable are available.

Self-management support is defined as the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems, including regular assessment of progress and problems, goal setting, and problem-solving support. Health literacy is defined as the ability to read, understand, and act on health care information. Specifically, improvement in this area encompasses four features of successful programs: (1) providers communicate and reinforce patients’ active and central role in managing their illness; (2) practice teams make regular use of standardized patient assessments; (3) evidence-based programs are used to provide ongoing support; and (4) collaborative care planning and patient-centered problem solving result in an individualized care plan for each patient and support from the team when problems are encountered (Glasgow et al., 2002).

Rationale for Selection

Impact

According to the National Adult Literacy Survey, 40–44 million of the 191 million adults (21 percent) in the United States are functionally illiterate: they read at or below the fifth-grade level or cannot read at all (American Medical Association, 2002). Another 50 million adults (25 percent of adult Americans) are marginally literate: they are able to locate and assimilate information in a simple text, but are unable to perform tasks that require them to assimilate or synthesize information from complex or lengthy texts (American Medical Association, 2002). The Journal of the American Medical Association reported in 1999 that 46 percent of American adults are functionally illiterate in dealing with the health care system (American Medical Association, 2002). Patients with low literacy are frequently ashamed and hide it. A 1996 study of patients with reading difficulty confirmed that 67 percent had never told their spouse and 19 percent had never told anyone about their reading problem (American Medical Association, 2002).

People with low literacy skills have to rely on remembering what health professionals tell them. Recall of medical instructions is often poor; one study showed that people remembered only 14 percent of spoken instructions for managing fever or sore throat (Pfizer, 1998). A 1997 study of patients in two public hospitals found that those with inadequate literacy skills were five times more likely to misinterpret their prescriptions than patients with adequate reading skills, and averaged two more doctor visits per year than those with marginal or adequate literacy skills (American Medical Association, 2002). In one study, 23 percent of English-speaking and 34 percent of Spanish-speaking respondents were found to have an inadequate ability to read and comprehend medical information in their spoken language. Furthermore, of those with low ability to read medical information, only 55 percent reported having someone in their household who could read for them (Pfizer, 1998).

The estimated additional health care expenditures due to low health literacy skills total about $73 billion. Employers may be financing as much as 17 percent of these additional expenditures (American Medical Association, 2002).

Improvability

Self-management support is critical because patients and their families are the primary caregivers in chronic illness (Von Korff et al., 1997). There is evidence that in the current system, even minimal health education is inadequate for people with chronic illness: just 45 percent of persons with diabetes received

formal education on managing their condition in 1998; 42 percent of patients with a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia received counseling or education on diet and nutrition in 1997; and 8.4 percent of patients with asthma received formal patient education in 1998 (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). However, more than education is required for outcome change to occur. As noted by Norris (Norris et al., 2001) in a systematic review of diabetes self-management training: “It is apparent that factors other than knowledge are needed to achieve long-term behavioral change…and improved personal attitudes and motivations are more effective than knowledge in improving metabolic control in type II diabetes.”

There is strong evidence that support for self-management is a critical success factor for chronic disease programs. For example, a metaanalysis of primary care diabetes programs found that 19 of 20 interventions including a self-management component had improved a process or outcome of care (Renders et al., 2001). In addition, a study that investigated the effect of self-management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in the proportion of subjects reporting hospitalizations and emergency room visits, unscheduled doctor visits, days lost from work, and episodes of nocturnal asthma (Gibson et al., 2000). A companion review analyzed trials that employed only limited education interventions and concluded that education did not have a significant effect unless it was coupled with an action plan, self-monitoring or regular review (Gibson et al., 2002).

With regard to health literacy, use of both written and verbal communication has been shown to be the most effective way of increasing patient understanding and compliance. (American Medical Association, 2002). Research with junior college students, for example, showed that recall of spoken medical instructions was enhanced by having pictographs representing those instructions present during learning and recall (Pfizer, 1998). The fact that the Hispanic subjects in the study did especially well in recalling pictograph meanings suggests that this approach may be helpful with groups for whom English is a second language.

Several measures of literacy have been found to correlate significantly with comprehension. The time spent reading sample leaflets and finding answers to questions about the documents was positively and significantly associated with comprehension measured by a true-false test. Two pronunciation measures and a literacy test based on correctly defining drug terminology also correlated significantly with true-false test comprehension (American Medical Association, 2002).

Inclusiveness

Poor health literacy is a widespread problem that affects people of all social classes and from all ethnic groups. Functional health literacy is worst among the elderly and low-income populations, impacting more than 66 percent of U.S. adults aged 60 and over and approximately 45 percent of all adults who live in poverty. Thus, the populations most in need of health care are least able to read and understand information needed to function as a patient (American Medical Association, 2002; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000).

Appropriate Treatment for Persons with Mild/Moderate Persistent Asthma

Aim

To ensure that all persons with mild/ moderate persistent asthma receive appropriate treatment with pharmacotherapy and suitable self-management support.

Rationale for Selection

Impact

It is estimated that in the United States, 14.6 million persons have active asthma (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001a). In 1999, an estimated 478,000 persons were hospitalized (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999b) and 2 million sought emergency care for acute asthma exacerbations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999a). While death from asthma is almost always considered preventable, over 4,600 persons in the United States died from this condition in 1999 (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2002).

In 1998, the economic burden associated with asthma was estimated at $12.7 billion annually. This figure includes nearly $7.4 billion in direct health care expenditures and an additional $5.3 billion in indirect costs. Loss of school days alone accounts for nearly $1.1 billion annually (Weiss and Sullivan, 2001). The inflation-adjusted costs of asthma have risen over the past decade (Weiss et al., 2000). Despite these increases in costs, however, there have been few clear signs that health care for those with asthma has substantively improved.

Numerous studies published throughout the 1990s and as recently as 2001 reveal that guidelines for asthma care are not being followed (Diette et al., 2001; Hartert et al., 2000; Legorreta et al., 1998). A number of national public and private agencies continue to recognize the suboptimal care and clinical outcomes for this disease. The United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), through its Healthy People 2010 initiative, calls for reductions in asthma hospitalization rates (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) has added a performance measure to the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) that is aimed at improving the use of anti-inflammatory medications for persons with persistent asthma (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1997). Most recently, the American Medical Association has focused on the importance of improving of asthma care through its physician-based measures (Antman, 2002).

The use of antiinflammatory medications and asthma education, including the provision of self-management support, are essential to improved asthma care. However, a number of studies suggest that health system redesign may also be required to optimally improve asthma care and thereby clinical outcomes (Evans et al., 1999; Greineder et al., 1999; Mayo et al., 1990; Zeiger et al., 1991). Studies such as the recently reported work of the Pediatric Asthma Care Patient Outcomes Research Team suggest that provider education alone will not significantly improve asthma outcomes without system redesign through a planned asthma care approach (Finkelstein et al., 2002).

Improvability

Since the late 1980s, there has been mounting evidence of substantial variations in asthma care and of the inadequate or suboptimal nature of much of the care provided (Diette et al., 2001; Hartert et al., 2000; Legorreta et al., 1998). In response to this problem, in 1987 the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute convened a national expert panel to develop guidelines for the treatment of the disease. These guidelines, first published in 1991 (National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, 1991) and updated in 1997 (NHLBIUSPHS, 1997) and 2002 (NAEPP Expert Panel Report, 2002), provide a benchmark by which to view the current

practice of asthma care.

One of the cornerstones of these guidelines is the use of anti-inflammatory medications for the treatment of persons with persistent asthma. A number of different medications make up this therapeutic group, and of these, inhaled corticosteroids have been recommended as the preferred therapy (NHLBIUSPHS, 1997). There are also a number of other key elements to the guidelines, few of which are as commonly agreed upon as the need to provide asthma education focused on support for self-management of the disease (NHLBIUSPHS, 1997).

Inclusiveness

Afflicting more than 14 million persons, asthma is a disease that affects all segments of the population—children and adults, males and females, urban and rural populations, and the wealthy and the poor (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001a). At the same time, perhaps the most important problem related to asthma care is the disproportionate impact of poor care on minority populations and persons of lower socioeconomic status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998; Grant et al., 2000).

Asthma meets the inclusiveness criterion as it relates to the health care system. Care for persons with asthma extends across the primary care specialties of pediatrics, family medicine, and internal medicine. It also is an important health care concern for two subspecialty groups—allergists and pulmonolgists. Within asthma care, there are important lessons for outpatient, emergency department, and hospital-based care.

Cancer Screening That Is Evidence-Based

Aim

To enhance the effectiveness of screening programs designed to prevent colorectal and cervical cancer. More specifically, the aims are to increase the number of individuals who are offered appropriate screening for these cancers and to ensure that timely follow-up is provided.

In this report, colorectal and cervical cancer are used as examples, with the goal that effective systems-based interventions implemented for these two cancers could serve as models for other cancers where an evidence base is documented for screening or could be used once one has been established.

Rationale for Selection

Impact

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer among men and women in the United States, with an estimated incidence of 148,300 cases annually. In 2002, 56,600 Americans died from colorectal cancer, making it the nation’s second leading cause of cancer-related death. Lifetime risk for developing colorectal cancer is approximately 6 percent with over 90 percent of cases occurring after age 50 (American Cancer Society, 2002). The estimated long-term cost of treating stage II colon cancer is approximately $60,000 (Brown et al, 2002).

Cervical cancer is the ninth most common cancer among women in the United States, with an estimated incidence of 13,000 cases annually. Cervical cancer ranks thirteenth among all causes of cancer death, with about 4,100 women dying of the disease each year (American Cancer Society, 2002). The incidence of cervical cancer has steadily declined, dropping 46 percent between 1975 and 1999 from a rate of 14.8 per 100,000 women to 8.0 per 100,000 women (Ries et al., 2002). Despite these gains, cervical cancer continues to be a significant public health issue. It has been estimated that 60 percent of cases of cervical cancer are due to a lack of or deficiencies in screening (Sawaya and Grimes, 1999).

Improvability

Early diagnosis of colorectal cancer while it is still at a localized stage results in a 90 percent survival rate at 5 years (Ries et al., 2002). The American Cancer Society’s (ACS) guidelines recommend screening for colorectal cancer beginning at age 50 for adults at average risk using one of the following five screening regimens: fecal occult blood test (FOBT) annually; flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years; annual FOBT plus flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years; double contrast barium enema every 5 years; or colonoscopy every 10 years (American Cancer Society, 2001). The United States Preventive Services Task Force strongly recommends screening for men and women 50 years of age and or older for colorectal cancer. Screening has been found to be cost-effective in saving lives, with estimates ranging from $10,000 and $25,000 life-year saved. However, data were insufficient to determine whether one screening strategy is superior to another (Pignone et al., 2002; United States Preventive Services Task Force, 2002b).

In a nationally conducted survey assessing current rates of use of colorectal screening tests, 40.3 percent of respondents reported having had FOBT and 43.8 percent sigmoidoscopy or colonscopy at some point in time. With regard to screening being done within recommended ACS guidelines, 20.6 percent of respondents reported having FOBT within 1 year, and 33.6 percent reported having had sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy within 5 years (Seeff et al., 2002). Another national survey found that between 1992–1998 only a slight increase was observed in screening for colorectal cancer, and in 1998, only 22.9 percent of respondents age 50 or older had been screened with a home administered FOBT in the past year or proctoscopy within 5 years (Nadel et al., 2002).

Widespread use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test over the past 50 years as a screening tool for cervical cancer has led to an estimated 70 percent decline in mortality from this disease

(Dewar et al., 1992; Saslow et al., 2002). Early detection of cervical cancer that is still localized results in a 5-year survival rate of 92 percent (American Cancer Society, 2002). The American Cancer Society’s guidelines recommend that cervical cancer screening should start 3 years after a woman begins having sexual intercourse, but not later than 21 years of age, given that cervical cancer risk has been associated with sexually transmitted infection with certain types of human papilloma virus (HPV). Subsequently, women should have a Pap test every 3 years (American Cancer Society, 2002; Saslow et al., 2002). A recently report controlled trial demonstrated that administration of a HPV vaccine reduced both the incidence of HPV infection as well as HPV related cervical cancer among study participants (Koutsky et al., 2002).

As of 2000, the median percentage of women who had had a Pap test within the past 3 years was 86.8 percent (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000a). Despite these high screening rates, more than 50 percent of women in the United States who develop cervical cancer have either never undergone screening or not done so within the 3 years prior to diagnosis (NIH Consensus Statement, 1996). These women are likely to be older, to live in rural communities, and to be of low socioeconomic status (Anderson and May, 1995). Immigrant women with limited English proficiency are at especially high risk of never undergoing screening (Harlan et al., 1991).

Outcomes of a 5-year demonstration project targeting low-income members of minority groups who received their health care through the Los Angles County Department of Health Services demonstrated that systems-level strategies increased cervical cancer screening rates among this traditionally high-risk group. Systems interventions included physician education to heighten awareness of screening guidelines; patient education regarding risk factors for cervical cancer; policy interventions, such as written protocols to ensure follow-up of abnormal results; and expanded capacity, for example, increased clinic hours and same-day appointments for referrals. During the intervention time period, patients were three times more likely to receive screening as compared with the base line year (Bastani et al., 2002).

Ambiguity among health plans regarding coverage for cancer screening is a systems-related barrier. A study in which insurance departments were queried nationally found that 28 states and Puerto Rico did not require coverage for cervical cancer screening. Lack of consensus pertaining to guideline use was also demonstrated. Fourteen states and the District of Columbia have adopted ACS guidelines for cervical cancer screening whereas seven states have elected to use nonconforming guidelines (Rathore et al., 2000).

Inclusiveness

African Americans have the highest incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer among racial/ethnic groups. Their mortality rate from the disease is 22.8 per 100,000 in the U.S. population and is at least double that of Asians/Pacific Islanders (10.7 per 100,000), American Indians/Alaskan Natives (10.3 per 100,000), and Hispanics (10.2 per 100,000) (American Cancer Society, 2002).

Vietnamese women have the highest age-adjusted incidence rate for cervical cancer (43 per 100,000) as compared with Japanese women, who have the lowest rate (15 per 100,000). Three ethnic groups have incidence rates of 15 per 100,000 or higher—Alaska Natives, Koreans, and Hispanics. African American women have an incidence rate of 13.2 per 100,000 for cervical cancer as compared with Caucasian women with a rate of 8.7 per 100,000. Mortality rates are also higher among African Americans than Caucasians, at 6.7 per 100,000 and 2.5 per 100,000, respectively (National Cancer Institute, 1996). African Americans are less likely than Caucasians to have their cervical cancer diagnosed at an early stage, with 44 percent of invasive cancers being diagnosed at a localized stage for the former as compared with 56 percent for the latter (American Cancer Society, 2002).

Children with Special Health Care Needs

Aim

To maximize the quality of care for children with special health care needs by addressing key processes of care, including care planning; use of preventive services; access to specialists, ancillary services, mental health services, and dental services; and care coordination.

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau defines this population as “those (children) who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally” (McPherson et al., 1998:138).

Rationale for Selection

Impact

Although children with special health care needs having substantial medical problems make up a relatively small proportion of the pediatric population, it is particularly important to focus on (1) maximizing the quality of their health care, because they are the most in need of services, and (2) increasing the cost-effectiveness of their health care, because it is the most expensive. In recent years, the prevalence of complex chronic conditions has dramatically increased even as medical, surgical, and technological advances have decreased the mortality rates for infants, children, and adolescents (Cadman et al., 1987; Gortmaker et al., 1990; Ireys, 1981; Newacheck et al., 1991; Newacheck et al., 1998; Newacheck and Taylor, 1992). Among the total pediatric population, it is estimated that 6.7 percent have significant activity limitations, 0.2 percent have a limitation in an essential activity, such as eating, bathing, or dressing; and 0.047 percent receive technology-assisted care.

While the proportion of severely afflicted children is relatively low, public and private health care costs for children with special needs are substantial (Ireys et al., 1997; Silber et al., 1999; United States General Accounting Office, 2000). For example, in fiscal year 1998, the 1 million disabled children on Medicaid constituted 7 percent of beneficiaries under the age of 21, but accounted for 27 percent of the $26 billion in payments for children (United States General Accounting Office, 2000).

Improbability and Inclusiveness

The process of developing, implementing, and monitoring a care plan that involves the active participation of the family and health professionals is the most effective vehicle for ensuring comprehensive, culturally sensitive, patient/family-centered care for this population. Developing a care plan using a collaborative, interactive process is important to help families gain an adequate understanding of their child’s chronic illness. Even when families play a central role in caring for their child, they often lack an adequate understanding of the condition (Carraccio et al., 1998). Increasing the parents’ (and patient’s) understanding through educational interventions has been shown to be beneficial (Bauman et al., 1997). Examples of successful interventions include programs for self-management of asthma (Clark et al., 1984), for children with cancer reentering school (Nolan et al., 1987), and for support for parents performing care coordination (Stein, 1983).

Care coordination should help the family obtain the necessary services and ensure that information is shared among all providers and agencies. The care plan should identify specific individuals responsible for coordinating services; all children with special needs benefit from such coordination. A parent, physician, nurse, social worker, school health professional, other medical home staff member, employee of a community-based service, or other support person (such as a family friend or clergy member) can potentially play a significant role in care coordination. School health providers should be included in developing the care plan because about half of children with special needs who require emergency admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) are of school age

(Dosa et al., 2001).

It is also important to note that special-needs patients and their family members often have or develop behavioral and mental health concerns (Breslau et al., 1982; Coupey and Cohen, 1984; Kronenberger and Thompson, 1992; Lavigne and Faier-Routman, 1993; Wallander et al., 1989). Children with special needs have higher rates of mental health problems compared with otherwise healthy children (Pless and Wadsworth, 1988; Wallander et al., 1988; Weiland et al., 1992), and these problems persist (Pless and Wadsworth, 1988). Unfortunately, these children and families too often do not receive needed mental health services (Ireys, 1981; Kanthor et al., 1974; Stein, 1983).

Children with special health care needs require access to a range of medical services, including primary care, medical subspecialty and surgical specialty services, other ancillary services, and dental care. Services are provided in the home, office, emergency room, and hospital. Home care, which continues to evolve, is a major component of health care delivery that must be integrated into the planning process (Guidelines for home care of infants, children, and adolescents with chronic disease. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Children with Disabilities, 1995; Ciota and Singer, 1992; Goldberg et al., 1994). In the office, routine pediatric health maintenance and condition-specific preventive care that addresses the prevention and early diagnosis of disease-related conditions or complications are often quite variable and difficult to track (Liptak et al., 1998). Urgent-care needs may supersede routine health care maintenance.

It is important to prepare families for unavoidable emergencies; this is especially so for families of children with special needs who require technology-assisted care (Emergency Medical Services for Children; Sacchetti et al., 1996). Dosa et al. (2001) report that children with special needs are more than three times more likely to have an unscheduled ICU hospital admission compared with previously healthy children. Among children with special needs, those who receive technology-assisted care are 373 times more likely to have an unscheduled ICU admission than other children with special needs. Almost one-third of ICU admissions of children with special needs are considered to be potentially preventable. Preventable admissions are more common for children with special needs who do not require technology-assisted care (38 percent) than for those who require such care (19 percent). Of preventable admissions, 56 percent are due to the physical or social environment and decisions made by the family.

There is a evidence that improved comprehensive medical care that integrates primary and specialty care has an impact on outcomes (Broyles et al., 2000; Reogowski J., 1998). Broyles et al. (2000) report that comprehensive care for infants of very low birth weight results in fewer life-threatening illnesses, intensive care admissions, and intensive care days without increasing the mean estimated cost per infant for all care.

Diabetes

Aim

To prevent the progression of diabetes through vigilant, systematic management of patients who are newly diagnosed or at a stage in their disease prior to the development of major complications.

Rationale for Inclusion

Impact

Diabetes ranks as the fifth leading cause of death in the United States, affecting 17 million people and a contributing factor to over 210,000 deaths in 1999. In 1997, the total annual economic costs attributed to diabetes-related illness was $98 billion. Of this total, $44 billion was direct costs, such as personal health care spending and hospital care, and $54 billion was indirect costs, including disability, premature mortality, and work-loss days (American Diabetes Association, 2002).

Diabetes predisposes individuals to many long-term, serious medical complications, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, blindness, kidney disease, neurological disease, and increased risk of lower-limb amputation. For example, diabetics have at least twice the risk of heart disease and stroke of their nondiabetic counterparts (American Diabetes Association, 2002). Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure; 33,000 people with diabetes developed kidney failure in 1997. And 12,000–24,000 people go blind each year as a result of the disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000d).

The lifetime cost of complications from diabetes was recently estimated to be about $47,000 per patient over 30 years on average. Management of macro vascular disease is the highest-cost component at 52 percent, followed by nephropathy (21 percent), neuropathy (17 percent), and retinopathy (10 percent) (Caro et al., 2002).

Improvability

Tight glycemic control has been shown to lower health care costs, reduce primary and specialty care visits, and afford short-term gains in quality of life for individuals with diabetes (Testa and Simonson, 1998; Wagner et al., 2001b). In addition, professional and organizational interventions, including aggressive follow-up and patient education, have been shown to contribute to better health outcomes for diabetics (Renders et al., 2001).

The Diabetes Quality Improvement Project (DQIP), a collaborative public-private venture founded in 1997 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), NCQA, and the American Diabetes Association, has developed standardized performance measures for accurately and reliably assessing the quality of diabetes care both within and across health care systems. DQIP measures include, for example, annual testing for HbAlc, annual foot exam and eye exam, biennial lipid testing, and control of blood pressure (Fleming et al., 2001). In a recently published study using DQIP measures to evaluate the quality of diabetes care in the United Sates from 1988 to 1995, it was found that 18.9 percent of participants had high HbAlc values, 58 percent had poor lipid control, 34.3 percent had poor blood pressure control, 36.7 percent did not receive an annual eye exam, and 45.2 percent failed to receive an annual foot exam (Saaddine et al., 2002).

Outcomes from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial confirmed that lowering blood glucose levels slows or prevents complications arising from type I diabetes. Individuals in the intensive therapy group experienced a 60 percent reduction in risk for eye disease, kidney disease, and neurological disease as compared with the standard treatment group (Implications of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, 2002). The lifetime benefits of intensive therapy could translate to approximately 8 years of additional sight, 6 years free from end-stage renal disease, and 6 years’ deferral of lower-extremity amputation relative to conventional treatment (Lifetime benefits and costs of intensive therapy as

practiced in the diabetes control and complications trial. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, 1996).

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study analyzed the effect of improved glucose control on type II diabetes. Findings from this longitudinal 14-year study demonstrated a 25 percent decrease in the overall microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) complication rate for patients who received intensive therapy and maintained HbAlc levels at <7 percent. Although no significant effect on cardiovascular complications was observed for lowering of blood glucose levels, an epidemiological analysis did demonstrate a continuous association between the risk of cardiovascular complications and elevated blood glucose levels. For example, a 1 percent point decrease in HbAlc resulted in a 25 percent reduction in diabetes-related deaths (Implications of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, 2002; King et al., 1999).

Diabetes is a prime candidate as a priority area because convincing guidelines, a robust set of measures (for example, from DQIP) and known ways of improving delivery of care already exist. Diabetes could serve as a model for improving quality of care for other chronic diseases, particularly with regard to facilitating patient self-management and the active involvement of a multidisciplinary health care

|

Box 3–8 Diabetes The American Diabetes Association recognizes HealthPartners Medical Group of Minnesota as a model for diabetes care. Key components of the HealthPartners diabetes program include a diabetes registry that provides clinicians with automated reminders for needed services; use of interdisciplinary teams including physicians, diabetes nurse specialists, social workers, and mental health professionals; education programs, including counseling on diet and exercise; and implementation of a staged approach to diabetes management, with an action plan and timelines for stepping up care to meet therapy goals. As a result of these multifaceted interventions, improvements in both blood sugar and lipid control were observed over a 1-year period. For example, the proportion of patients with acceptable HbAlc levels (below 8 percent) rose from 60.5 to 68.3 percent, and the proportion of patients with acceptable control of their LDL (bad cholesterol) levels rose from 48.9 to 57.7 percent (HealthPartners, 2000; Sperl-Hillen et al., 2000). |

team. Improved care for this condition could also stimulate an approach that involves treating other risk factors (cardiovascular disease, hypertension, renal disease) through aggressive management of the disease as opposed to treatment of end-stage complications.

Inclusiveness

During the 1990s, the prevalence of diabetes increased by 33 percent. Most notably, this increase was seen in both males and females, across ethnic groups and educational levels, and among all age groups (Mokdad et al., 2000).

Racial and ethnic disparities have been documented with regard to the treatment of chronic diseases including diabetes (Chin et al., 1998; Institute of Medicine, 2002). For example, one study looking at racial disparities in quality of care for Medicare enrollees found that African Americans with diabetes were less likely than Caucasians to receive eye examinations (Schneider et al., 2002). African Americans are three times more likely than Caucasians to die of diabetes-related causes. And American Indians/Alaska Natives are 2.5 times more likely and Hispanics 1.5 times more likely to die of diabetes than Caucasians or Asians/Pacific Islanders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000d).

End of Life with Advanced Organ System Failure

Aim

To arrange care so that people facing the end of life with heart, lung, or liver failure will have as few frightening exacerbations as possible, as few symptoms as possible, and as many opportunities for life closure and control of the circumstances of death as possible.

Rationale for selection

Impact

Heart, lung, or liver failure is one of the more common conditions experienced at the end of life (Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Thoracic Society, 1995; Gillum, 1993; Higgins, 1989; Levenson et al., 2000; Lynn et al., 2000; McAlister et al., 2001; Rich, 1997; Rich, 1999; Roth et al, 2000; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). People live with these conditions for long periods of time that have become longer now that better treatments slow the progression of illness. However, the conditions still cause death eventually, and living for a long time in perilous circumstances poses its own challenges. Heart failure is one of the most common hospitalization diagnoses in Medicare, and lung failure is close behind (Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Thoracic Society, 1995; Rich, 1999). As many more people survive their first few heart attacks, their first episodes of lung infection with emphysema, and their first bleeds with cirrhosis, many more live with advanced organ system failure.

The normal course of such conditions is one of stability and comfort on a “usual” day, with a string of those usual days being interrupted by a rather sudden exacerbation in response to some stress (Levenson et al, 2000; Lynn et al, 2000; Roth et al, 2000). A fever, a small new heart attack, or a bowel problem is enough to disturb the fragile balance being enjoyed by the patient (Burns et al., 1997; Chin and Goldman, 1996). Often, one of these exacerbations is the cause of death, but the timing of that eventuality generally remains unclear to within a week of the patient’s dying. Good care for this population requires reducing the rate of exacerbations, diminishing their effects, and planning for the eventuality of an unsurvivable episode.

Improvability

Many studies have shown that the rate of exacerbations can usually be cut in half, and sometimes much more (McAlister et al., 2001; Rich, 1997; Rich, 1999). Doing so requires self-care education, reliable availability of medications, early intervention at the least sign of trouble, and mobilizing of services to the home setting. Most important, good care requires continuity in the care plan and in caregivers across time and settings. Some hospice programs support nearly all patients at home at the end of life (Lynn et al., 2000).

Most health care is loosely organized by referral patterns, and patients from the same neighborhood may go to disparate providers. In end-of-life care for persons facing organ system failure, services are probably best organized so that the same provider of services takes care of all persons in one area, or at least so that only a very small number of providers are working in one area. The number of persons affected by advanced heart, lung, and liver disease is not large, so even urban areas cannot efficiently support more than a few services for around-the-clock availability.

Improving care for this population also requires close monitoring and rapid responses. When a patient becomes quite ill, mobilizing of services-including both urgent and end-of-life services-to the home is essential. Thus, implementing good care for this population requires learning how to work in communities, how to plan ahead, and how to provide good care for very sick people in their homes and nursing homes.

Inclusiveness

Heart, lung, and liver failures account for about one-fifth of all fatal illness in the United States (Lunney et al., 2002), and they strike rather equitably across all genders, ethnic groups, and geographic areas. Cirrhosis tends to kill somewhat earlier than the other

|

Box 3–9 End of Life with Advanced Organ System Failure: A Current and Future Scenario In the current system, an elderly man lives with his wife in a small duplex, and their son lives nearby. As the man has become more disabled with heart attacks and progressive heart failure, his living arrangements have become more constrained. The family moved his bed to the living room, they arranged a long ramp to the door, and they changed the family diet to avoid salt. Nevertheless, he goes into an episode of “failure” every few months and is rushed to the hospital by the emergency ambulance, struggling to breathe. His wife lives in terror of these episodes, and shakes and trembles for days afterwards. She has lived through breast cancer and a stroke herself, and she worries all the time about what would happen to her husband if she died first, and what would happen to her if he died first. Their assets have been spent, and they routinely skimp on their prescription medications, since otherwise they could not meet their rent and food bills. Their son helps out by keeping the place repaired, but he works as a clerk in a convenience store and does not really have funds to assist his parents. Every time the man is hospitalized, he has a different set of doctors, who never seem even to have his medical record. Between hospitalizations, he is scheduled for a follow-up visit in “resident’s clinic,” but he does not usually go since it costs so much and seems to do very little good. He does not understand his medications, does not weigh himself, does not know what to do if he starts to become short of breath, and has had no conversations with any physicians in which it was implied that this condition will eventually take his life. In a transformed health care system, the same elderly man and his wife are enrolled in a complex care management program that ensures that they receive good medical services and helps with financial planning, family support, and advance care planning. Both have come to understand how to manage medicines and weight, and know what extra medications to take at the earliest signs of trouble. The man has had only two more hospitalizations–one for prostate trouble and one for heart failure brought on by a bad cold with a fever. As his condition has worsened, nurses have become available at home. As planned, he eventually dies at home, and the same care team continues to support his wife with the health and living challenges she faces. |

conditions, with many deaths occurring before Medicare eligibility (Roth et al., 2000). Heart and lung failures tend to reach life-threatening levels in the 65–80 age group (Lunney et al., 2002).

Frailty Associated with Old Age

Aim

To arrange care so that people in frail health can count on living in optimally safe environments, free of unnecessary threats to their physical safety, assisted as necessary with the tasks of daily living, encouraged to maintain functioning whenever possible, treated early for complications, and with care shaped by advance care plans that reflect patient and family preferences.

Rationale for Selection

Impact

As Americans routinely no longer die from infections, childbirth, early heart attacks, and the various threats to longevity that were commonplace just a few score years ago, they increasingly live out the end of life in advanced old age, afflicted by multiple medical problems, significant disability, and limiting social challenges, ultimately spiraling into a condition tht can be characterized as frailty (Fried and Walston, 1998; Walston and Fried, 1999). This condition is marked by having multiple chronic ailments and a lack of reserve capacity to endure health setbacks in most body parts and systems (Buchner and Wagner, 1992; Fretwell, 1993; Fried et al., 2001). About half of the people affected past the age of 85 have cognitive deficits from dementia, stroke, or other causes. Many have problems with falls or develop other impediments to mobility. Many have heart or lung problems, but even more have problems with vision, hearing, foot pain, and bowel discomfort (Fried and Guralnik, 1997). Approximately two-fifths of Americans now live with frailty for a few years before dying (Lunney et al., 2002).

The average person living with frailty at the end of life probably faces more than 2 years of self-care disability (Manton, 1989). Unfortunately, the current American health care system was never designed to support large numbers of people with cognitive and other self-care disabilities. Services for frail older adults are often poorly coordinated, entail differing and mismatched sets of eligibility criteria and coverage, and are inadequate to meet important care needs (Moon, 1996; Wagner et al., 1996). The shortcomings have been documented most extensively with regard to nursing facility care, but undoubtedly affect family care at home, paid help at home, hospice care, assisted living settings, and other strategies for services to this population (Bodenheimer, 1999).

The challenge of providing for the large numbers of elderly anticipated over the next quarter century is widely regarded as a major crisis for health care and for society generally (American Medical Association white paper on elderly health. Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs, 1990). Not only will the numbers of dependent elderly nearly double, but also the availability of family caregivers will actually decline.

Improvability

Achieving excellence in care for this vulnerable population will take some time, but some of the needed changes are well documented, highly visible, and strategically important, and it is these changes that the committee recommends making a priority. For example, good care systems have exceedingly low rates of skin breakdown from pressure and poor hygiene. Until the last few weeks of life, when some patients do not want to be turned, the rates can be kept to only a few percent. However, doing so requires assiduous nursing care around the clock (Prevention Program Reduces Incidences of Pressure Ulcers by Up to 87%, 2002; Bates-Jensen, 2001).

As another example, the death of frail patients is no surprise to anyone when it occurs. Advance care planning averts the inappropriate implementation of rescue efforts not desired by patient and family and offering little benefit. In some parts of the country, virtually all persons living in nursing homes or receiving regular home care for frailty have advance care plans that address what is to be done about

hospitalization, resuscitation, and other aggressive means to sustain life. In most parts of the country, however, advance care planning is the exception (Fried et al., 2002; Kolarik et al., 2002; Schwartz et al., 2002).

As a final example, many frail people sustain completely preventable injuries due to unsafe home environments. Surveillance of the risks at home, together with the use of improved lighting, warning systems, floor coverings, grip bars, and other environmental modificationsm, has been shown to greatly reduce the incidence of falls and injuries. Yet these measures are not routinely provided or even available to most frail patients (Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention, 2001; Fleming and Pendergast, 1993; Tinetti and Williams, 1998).

In addition, reliable care for the elderly should include interventions such as increased physical activity and strengthening, to prevent further declines in function. For example, in a program designed to prevent functional decline for frail elderly persons, participants were assessed on eight activities of daily living3 at 3,7, and 12 months, and the results were compared against baseline scores on a disability scale. Moderately frail persons who received the home-based interventions, which consisted of physical therapy targeting improved balance, muscle strength, ability to transfer from one position to another, and mobility, demonstrated less functional decline over time as compared with the control group (Gill et al., 2002).

Improving care for the frail elderly and the provision of support for their family caregivers will require transforming much of health care for this population to a chronic illness model. Continuity and reliability are priorities. Given the large numbers of people involved and the scarcity of caregivers, efficiency needs to be built in from the start. As noted, for example, reducing rates of skin breakdown to the extent possible will require adequate round-the-clock nursing care, thus pressuring the care system to attend to personal care and not overemphasize procedures. The development of advance care plans for most frail persons will require that professionals learn to counsel patients and families about their future prospects and to maintain effective continuity of the care plan over time. And preventing falls and injuries will necessitate mobilizing services to the places where the frail live, again requiring caregivers to adapt to the needs of this population.

Inclusiveness

Frailty awaits those who survive long enough simply to have diminished reserves, as well as those who encounter mental decline in old age. The condition is now so dominant at the end of life that all ethnic groups, both genders, and all parts of the country are affected roughly equally.

Hypertension

Aim

To reduce the incidence of complications resulting from inadequately treated hypertension (i.e., coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, peripheral vascular disease, and stroke) through early detection, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up.

Rationale for Selection

Impact

Hypertension (high blood pressure) affects approximately 43 million Americans aged 18 or older, representing 1 in 4 adults.

Approximately 20 million of these individuals are not receiving necessary blood pressure medication, and for another 12 million who are being treated, the condition is inadequately

Table 3–1. Estimated Number of Americans Age 25 and Older by Category of High Blood Pressure

|

|

Population in Million |

|||

|

Age group |

Treated, Controlled |

Treated, Uncontrolled |

Aware, Untreated HBP |

With HBP, Unaware |

|

25–34 |

1.7 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

2.9 |

|

45–64 |

4.5 |

4.2 |

2.8 |

4.4 |

|

65+ |

3.5 |

6.9 |

2.3 |

5.8 |

|

SOURCES: (Burt et al., 1995; Hyman and Pavlik, 2001) |

||||

Table 3–2. Extent of Awareness, Treatment, and Control of High Blood Pressure Race/Ethnicity 1988–1994

|

|

Percent of Population with High Blood Pressure |

|||

|

Race/ Ethnicity |

Treated, Controlled |

Treated, Uncontrolled |

Aware, Untreated HBP |

With HBP, Unaware |

|

Caucasians |

24 |

29 |

17 |

31 |

|

African Americans |

24 |

32 |

17 |

27 |

|

Mexican Americans |

15 |

25 |

19 |

41 |

|

SOURCES: (Burt et al., 1995; Hyman and Pavlik, 2001) |

||||

controlled (Burt et al., 1995). In 1999, high blood pressure was the primary cause of death for 42,997 Americans and was a contributing cause of death in 227,000 cases. In 2002, the economic costs of hypertension totaled $47.2 billion (American Heart Association, 2001). Table 3–1 presents the estimated number of Americans with high blood pressure by age group.

Overall, 32 percent of people with high blood pressure are unaware they have the disease. If left untreated hypertension can lead to several life-threatening complications, such as stroke, heart attack, heart failure, and kidney failure (American Heart Association, 2002). Table 3–2 shows the extent of awareness of high blood pressure among different racial/ethnic groups.

According to a recent study, the lifetime risk of developing hypertension for middle-aged and elderly individuals is 90 percent.

Notably, while women’s risk for hypertension remained constant over the two time frames evaluated in this study (1952–1975 and 1976– 1998), men’s risk increased by 60 percent (Vasan et al., 2002).

Improvability

Data from the Framingham Heart Study and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey II indicate that lowering of diastolic blood pressure by a slight percentage–2 millimeters of mercury (mm/Hg) could result in a 17 percent decrease in the prevalence of hypertension, a 6 percent decrease in coronary heart disease, and a 15 percent reduction in stroke (Cook et al., 1995). However, statistics released by the NCQA in its 2002 State of Health Care Quality report indicate that of those being treated for hypertension only 55.4 percent maintain their blood pressure at an adequate level. Although this current rate is unacceptable, gains have been made, as the rate was 39 percent in 1999 (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2002).

A systematic review of 18 long-term randomized controlled trials revealed that the use of low-dose diuretic therapy was effective in reducing stroke, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and total mortality. Additionally, beta blockers were demonstrated to decrease the incidence of congestive heart failure and stoke (Psaty et al., 1997). These findings are consistent with the guidelines of the Sixth Report of the National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC-VI), which recommends the use of diuretics and/or beta blockers for initial drug therapy for patients with hypertension (The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure, 1997). Despite these evidence-based guidelines, a recent study revealed that in 62 percent of visits, physicians failed to introduce proper pharmacologic therapy to patients with a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm/Hg or higher, the JNC-VI recommended cut-off point. On average, physicians were willing to accept a higher cut-off point of 150 mm Hg before believing it necessary to initiate or change drug therapy (Oliveria et al., 2002).

The most recent recommendations of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee for primary prevention of hypertension include a two-pronged approach employing population-based strategies and an intensive strategy targeting individuals known to be at high risk, such as African Americans. The recommendations focus on six lifestyle modifications that have not only been proven to be effective in preventing an increase in high blood pressure at the population level, but also can be readily applied to individuals with hypertension or with high normal blood pressure: weight loss; dietary sodium reduction; increased physical activity; moderation of alcohol consumption; potassium supplementation; and modification of diet to include foods rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and to reduce the intake of saturated and total fat (Whelton et al., 2002).

Inclusiveness