Chapter Four

Process for Identifying Priority Areas

Guiding Principles

The initial set of priority areas was chosen to guide the nation in taking the first steps toward a systematic redesign of the health care system. As discussed in Chapter 2, the committee focused on areas that have a high impact; are most amenable to improvement; and are broadly inclusive in several respects, cutting across the entire life span, involving the continuum of care from disease prevention through the end of life, and affecting a range of demographic groups for which inequities in health care need to be redressed.

The committee developed its recommendations using an evidence-based approach, supplemented by the perspectives of experienced experts. It relied on quantitative data, from national datasets to compare the burden of disease for specific conditions, evaluating such items as population-based estimates for prevalence and costs. The design of these measures allows for estimates of ranking and for rough comparisons across conditions. The committee synthesized available evidence from the literature and experience to judge the extent of improvability for each area through systems change.

The salient studies do not share common interventions or outcome measures and are often not reported in the published literature. Thus, the committee took both a quantitative and qualitative approach when assessing the potential for systems change, and employed data as well as the negotiated consensus of the group to decide whether a priority area under consideration met a threshold of confidence for improvability. The committee also considered the degree to which effective systems change in one area had the potential to diffuse to other areas in which improvements would be welcome. Making this determination required judgment as well, as there can be no historical evidence for the ability of improvement in one priority area to generate

improvement in similar conditions or settings until systems changes have actually been implemented. Thus the committee turned to illuminating examples of systems transformation provided by workshop presenters and presented in the literature, and took into account the value of these experiences.

Recognizing that no priority-setting process is perfect, the committee believed it essential to make its process as transparent as possible, being clear and open about the bases for its decisions (Daniels, 2000; Daniels and Sabin, 1998). The committee also decided that the process it adopted would have to be dynamic, capable of evolving over time, and characterized by ongoing interaction among its various components. A feedback loop would be needed as well to allow for periodic revisiting and updating of the priority areas and continuous assessment of progress.

This chapter describes the process used by the committee to identify the priority areas in the brief period of time available for this study. Additionally, a revised process is recommended for the future determination of priority areas, based upon the committee’s experience with its initial process.

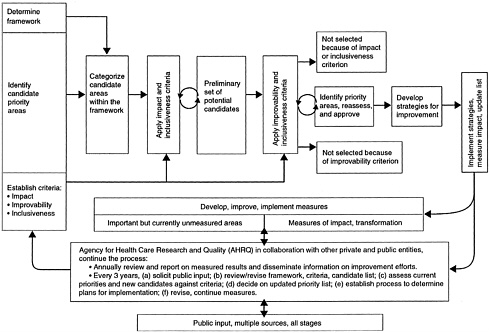

FIGURE 4–1 Process model used by the committee.

Process use by the Committee

The process used by the committee, summarized in Figure 4–1, consists of the following steps:

-

Determine a framework for the priority areas.

-

Identify candidate priority areas.

-

Establish criteria for selecting the final priority areas.

-

Categorize candidate areas within the framework.

-

Apply criteria to screen the candidates.

-

Identify priority areas; reassess and approve.

Although the process appears to be linear in fashion, it is much more dynamic than a succession of orderly steps. The decisions required in the first three steps, for example, are all closely interrelated.

Determine Framework

The framework used by the committee is discussed in Chapter 1.

Identify Candidate Priority Areas

In developing an initial candidate list, the committee drew on a variety of sources. In addition to the collective knowledge and broad expertise of its members, the committee made use of feedback received from presenters and the public at a workshop held in May 2002 (see Chapter 1 for a brief description of the workshop and Appendix B for its agenda).

The committee also considered the work done by other groups in the area of the burden of chronic conditions/diseases. It reviewed datasets on the economic burden of chronic diseases compiled by the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, (Cohen, 2001; Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2000, 2002). In addition, although this study’s focus was national, the committee considered statistics from the Global Burden of Disease Study (Michaud et al., 2001; Murray and Lopez, 1996). The committee also reviewed many of the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) standardized performance measures currently used by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) in its accreditation process (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2002).

The committee then looked to the work of other groups that have established lists of targeted or priority conditions and areas to meet their specific needs. These groups included the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) MEPS, the Veterans Administration’s (VA) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI), the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA) Health Disparities Collaboratives, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Quality Improvement Program (see Table 4–1 and Appendix C for more detail). To examine priorities pertaining to preventive services, the committee considered the work of Partnership for Prevention (see Table 4–2 and Appendix C). In addition, although the setting of research priorities was outside the purview of this committee, the criteria employed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for assessing health needs1 proved helpful in balancing the criteria established for screening candidate priority areas (see Appendix C). After utilizing all of the above resources, the committee compiled a list of over 60 candidate priority areas.

Establish Criteria

The criteria used by the committee in selecting the priority areas are described in Chapter 2.

Categorize Candidate Areas Within the Framework

Once a pool of candidate areas had been established, the candidates were organized within the categories of the framework. For example, the committee placed diabetes under chronic care, tobacco dependence treatment under preventive care, pain control under palliative care, acute respiratory infection under acute care, and care coordination under cross-cutting systems interventions. At this point, it became evident to the committee that the framework was a useful organizing tool, but its categories were too rigid. Many of the initial candidates fell quite easily into more than one category. For example, stroke could be viewed as the start of a chronic condition or an acute episode. Cancer could fall under chronic conditions, or it could perhaps be more appropriately placed under preventative care, such as screening for colorectal cancer.

|

1 |

Number of people with a disease, number of deaths caused by a disease, degree of disability caused by a disease, degree to which a disease shortens a normal productive lifetime, economic and social costs of a disease, and the need to respond rapidly to control the spread of a disease (National Institutes of Health (NIH), 1997) |

Although appearing in more than one category was a type of triangulation, it also exposed a weakness of this classification scheme. Nonetheless, while remaining cognizant of this limitation, the committee proceeded to organize the first-cut list of candidates in this fashion to facilitate application of the process model. In later deliberations and in determination of the final list of priority areas, the committee shifted away from placing areas within these categories and instead used the categories as part of a test of inclusiveness across the spectrum of areas. The framework thus served as a useful screen at the end of the process to assess the balance of the portfolio.

Being mindful that the number of priority areas requested by AHRQ was approximately 15 but no more than 20, the committee at this point set preliminary targets for the final portfolio of areas from each category of the framework. Chronic conditions received the largest allocation of approximately 8 final candidates because they were seen as far-reaching in their ability to spark change. Each of the other four categories of the framework (preventive care, acute care, palliative care, and cross-cutting systems interventions) was assigned approximately 3 areas each. As noted earlier, the committee believed it important to include on the final list a few cross-cutting areas (as opposed to specific conditions) that could be broadly applied to improve health care quality, especially since it was not possible to select every condition worthy of improvement.

Apply Criteria to Screen Candidates

After identifying a list of candidate priority areas and categorizing them within the framework, the committee applied the impact, inclusiveness, and improvability criteria to each candidate, being particularly sensitive to the impact on disadvantaged populations. Two subgroups were formed to accomplish this task. One group examined the areas within the chronic, acute, and palliative care categories; the other analyzed those within the categories of preventive care and cross-cutting systems interventions. To facilitate this step, a matrix was developed in which each priority candidate was cross-referenced against the criteria. The cells of the matrix were then filled in with supporting data and their source.

Identify Priority Areas

The subgroups discussed the extent to which each of the candidates met the criteria and ranked them accordingly. They then selected their top candidates for presentation to the full committee. The committee discussed each of the proposed candidates, continually comparing them against the criteria. During these deliberations, some areas were refined and narrowed, while others were broadened. The committee then approved a final list. Candidates not chosen were eliminated because they were relatively weak on the impact or inclusiveness criterion. Others did not meet the improvability criterion because of a lack of scientific evidence and clinical guidelines for effective interventions and valid and reliable measures; these represent important needs for future research. See Chapter 3 for the committee’s recommended list of priority areas.

TABLE 4–1 Comparison of Priority Areas from Selected Sources

|

Condition |

AHRQ/MEPS |

VA/QUERI |

HRSA/ Collaboratives |

CMS/Quality Improvement Program |

|

Diabetes |

|

|

|

|

|

Congestive Heart Failure |

|

|

|

|

|

Ischemic Heart Disease |

|

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

|

|

|

|

|

Acute Myocardial Infarction |

|

|

|

|

|

Stroke |

|

|

|

|

|

Depression/Mental Health |

|

|

|

|

|

Asthma |

|

|

|

|

|

HIV/AIDS |

|

|

|

|

|

Breast Cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

Cervical Cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

Colon Cancer |

|

|

|

|

|

Arthritis |

|

|

|

|

|

COPDb |

|

|

|

|

|

Spinal Cord Injury |

|

|

|

|

|

Post Operative Infections |

|

|

|

|

|

Pneumonia |

|

|

|

|

|

Infant Mortality |

|

|

|

|

|

Immunization |

|

|

|

|

|

a Expected future collaboratives. b COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease SOURCES: AHRQ/MEPS-(Cohen, 2002; Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002); VA/QUERI-(Demakis et al., 2000; Feussner et al., 2000; Kizer et al, 2000). HRSA/Collaboratives-(Health Disparities Collaboratives, 2002; Stevens, 2002) CMS/Quality Improvement Program-D.Schulke, The American Health Quality Association, personal communication. |

||||

TABLE 4–2 Partnership for Prevention Priority Areas

|

Type of Service |

Services Delivered to Less Than 50% of Target Population |

|

Counseling |

Tobacco cessation for adults Alcohol and drug abstinence for adolescents Antitobacco message or advice to quit to adolescents Problem drinking for adults |

|

Screening |

Vision impairment among adults aged 65+ Colorectal cancer (fecal occult blood test and/or sigmoidoscopy) among all persons aged 50+ Chlamydia among women aged 15–24 Problem drinking |

|

Vaccine |

Adults > age 65 for pneumococcal disease |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from (Partnership for Prevention, 2002). |

|

Recommended Process for Determining Priority Areas

As noted, several valuable lessons were learned as the committee was applying the above process. This section presents the committee’s recommendations for further refinements to the process based upon these insights and assuming a longer time period for deliberations.

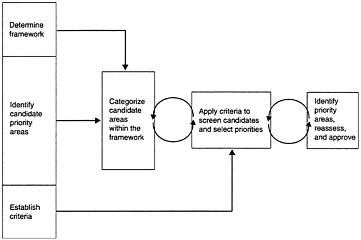

Since the committee’s task was over once it had identified the priority areas, its process did not include implementation and outcome assessment. The recommended model includes these critical follow-up components: implementing strategies for improving care in the priority areas, evaluating their outcomes, and reviewing/updating the list of priority areas. Figure 4–2 presents the committee’s recommended process for determining priority areas for a full and complete review. In this model, public input is solicited from multiple sources at all stages. The recommended process can be summarized as follows:

-

Determine a framework for the priority areas.

-

Identify candidate areas.

-

Establish criteria for selecting the final priority areas.

-

Categorize candidate areas within the framework.

-

Apply impact and inclusiveness criteria to the candidates.

-

Apply criteria of improvability and inclusiveness to the preliminary set of areas obtained in step 5.

-

Identify priority areas; reassess and approve.

-

Implement strategies for improving care in the priority areas, measure the impact of implementation, and review/update the list of areas.

Each step in this recommended process is discussed below.

Determine Framework

As noted, the initial framework used by the committee was advantageous for some purposes, such as the initial identification of candidates, but it was also found to be overly constricting. Given this limitation, future priority-setting processes will need to strike a balance between the need for categorization and the desire to capture the more dynamic and complex processes taking place for patients in the real world.

Identify Candidate Priority Areas

To identify potential candidates, an extensive review of relevant data should be conducted, as well as a thorough synthesis of similar work done by other groups. Input from the public should be aggressively solicited. In addition, future processes will need to examine:

-

Candidates that may become worthy of inclusion because issues associated with an area emerge, or measures are improved to allow more specificity about issues previously not measured, such as functional capacity.

-

Outcomes of efforts to improve quality in the initial priority areas to determine whether to retain or replace them on the list.

-

Candidates set aside in the past because of limits on the total number of priority areas, as well as improvability or measurement issues, to see whether changes have occurred that warrant their inclusion.

Establish Criteria

The criteria used by the committee are described in Chapter 2.

Categorize Candidate Areas Within the Framework

If a framework is used, the next step is to place the candidate areas into its categories. Chapter 1 details the initial framework adopted by the committee.

Apply Impact and Inclusiveness Criteria

Next, the impact and inclusiveness criteria should be applied to the initial pool of candidates using available data and public input. At this stage, individual areas should be ranked in terms of their clinical burden. A variety of data sources should be compared to ensure balance and inclusiveness in this process. Future applications of this approach to update the priority areas might well involve richer data analysis and more extensive feedback from the public and health professionals.

Apply Improvability and Inclusiveness, Criteria

The recommendation to apply the improvability criterion after the impact criterion does not reflect the former’s secondary status, but the fact that there was far less evidence available on improvability, and existing data could not easily be used for making comparisons across conditions. Therefore, the improvability criterion should be applied to high-impact areas to ensure that they can be improved within the current health system, and that evidence exists for believing that transforming the health system in these areas could result in widespread improvement for patients. Areas might be screened out at this step if they posed a large burden but were not improvable through interventions implemented within the health system. Finally, at each stage of the process, the list should be examined to ensure that it is inclusive across a range of populations, conditions, and quality improvement strategies.

Identify Priority Areas

The priority areas on the final list share a common set of features. The inclusion of each individual area is based on evidence of the need for improvement and of the likelihood that

current treatments, if applied more effectively, would substantially enhance health. Collectively, the areas encompass all age groups and types of care (preventive, acute, chronic, and palliative) and represent a range of sectors of the health care system (hospitals, ambulatory care, home health). The list of candidates that emerges after all the criteria have been systematically applied should be carefully reassessed to ensure, to the extent possible, that all the criteria have been adequately met.

Implement Strategies for Improving Care, Measure Impact, and Review/Update List of Areas

Once the set of priority areas has been identified, steps should be taken to prepare for follow-up. Doing so will first and foremost require the development of national strategies for improving care within each of the priority areas. Next, it will be necessary to implement those strategies and measure their impact using methods that are standardized and permit comparison across the diverse areas of quality improvement involved. This assessment must include measures of the degree to which the system has been transformed and of the clinical impact on patient care.

As such changes are effected, the list of priority areas should be reviewed and updated— optimally every 3 to 5 years. Other areas may need to be added to the list as the result of new data on impact or the development of new treatment strategies. Likewise, if strategies for improvement are effective, it may be possible to remove some areas from the list.

Recommendation 4: The committee recommends that AHRQ, in collaboration with other private and public organizations, be responsible for continuous assessment of progress and updating of the list of priority areas. These responsibilities should include:

-

Developing and improving data collection and measurement systems for assessing the effectiveness of quality improvement efforts.

-

Supporting the development and dissemination of valid, accurate, and reliable standardized measures of quality.

-

Measuring key attributes and outcomes and making this information available to the public.

-

Revising the selection criteria and the list of priority areas.

-

Reviewing the evidence base and results, and deciding on updated priorities every 3 to 5 years.

-

Assessing changes in the attributes of society that affect health and health care and could alter the priority of various areas.

-

Disseminating the results of strategies for quality improvement in the priority areas.

Recommendation 5: The Committee recommends that data collection in the priority areas:

-

Go beyond the usual reliance on disease-and procedure-based information to include data on the health and functioning of the U.S. population.

-

Cover relevant demographic and regional groups as well as the population as a whole, with particular emphasis on identifying disparities in care.

-

Be consistent within and across categories to ensure accurate assessment and comparison of quality enhancement efforts.

Recommendation 6: The committee recommends that the Congress and the Administration provide the necessary support for the ongoing process of monitoring progress in the priority areas and updating the list of areas. This support shall encompass:

-

The administrative costs borne by AHRQ.

-

The costs of developing and implementing data collection mechanisms and improving the capacity to measure results.

-

The costs of investing strategically in research aimed at developing new scientific evidence on interventions that improve the quality of care and at creating additional accurate, valid, and reliable standardized measures of quality. Such research is especially critical in areas of high importance in which either the scientific evidence for effective interventions is lacking, or current measures of quality are inadequate.

Discussion of Limitations

The model recommended by the committee should not be viewed as a formal, structured, quantitative process, but as an interactive and qualitative approach to solving the complex problem under the committee’s charge. It is too simplistic to think that a list of candidate priority areas could be screened through this step-by-step process to yield an unassailable final list. The committee struggled, for example, with how to balance the perceived need to make improvements in a particular area and a lack of evidence to support effective intervention at this point in time. There was debate over whether to focus on broader areas, such as heart disease, or narrower ones, such as hypertension. Some committee members believed that having a small number of priority areas might allow greater results within each area and facilitate the implementation of effective interventions. However, others believed that a small number of conditions might exclude the involvement of some health professionals and fail to meet the need for equity and breadth. In the end, the committee decided to lean toward a larger number of priority areas.

In trying to strike a balance between including too many and too few areas, the committee reached consensus that to achieve inclusiveness, it would recommend 20 areas, but it would select within most of these areas a specific focus that would be expected to yield both large and achievable benefits. In most but not all instances, this focus was placed on interventions designed to prevent or retard the progression of early disease or risk factors. Thus, for example, while the area of diabetes is very broad, the committee is recommending a special focus on aggressive treatment and control of the disease in its early stages, given the strong evidence that such early treatment can substantially delay or prevent later complications. As noted elsewhere in the report, however, a number of areas believed to be important in terms of impact were not included in the final list because of a lack of scientific evidence of improvability or the absence of valid, reliable, and widely available measures.

The committee also recognizes the obvious limitation of having a relatively small number of individuals engaged in its deliberations. Although a concerted effort was made to have diverse groups represented among the committee members, it was impossible to include all stakeholders. The committee also faced considerable time constraints. Nonetheless, the committee believes that due consideration was given to a wide array of candidate priority areas and input received from a broad range of researchers and interest groups. The committee’s recommended future process for priority setting would help address the limitations encountered during this study.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Unrealized Prevention Opportunities: Reducing the Health and Economic Burden of Chronic Disease.Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

——. 2002. The Burden of Chronic Diseases and Their Risk Factors.Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Cohen, S.B.2001. Enhancements to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to improve health care expenditure and quality measurement . In Proceedings of the Statistics in Epidemiology Section, American Statistical Association.

——. 2002. MEPS Enhancements to Support Healthcare Quality Measurements.Presented at April 1–2, 2002 Priority Areas for Quality Improvement Meeting.

Daniels, N.2000. Accountability for reasonableness. BMJ321 (7272): 1300–1.

Daniels, N., and J.Sabin. 1998. The ethics of accountability in managed care reform. Health Aff (Millwood)17 (5):50–64.

Demakis, J.G., L.McQueen, K.W.Kizer, and J.R. Feussner. 2000. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): A collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care38 (6 Suppl 1):I17–25 .

Feussner, J.R., K.W.Kizer, and J.G.Demakis. 2000. The Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): From evidence to action. Med Care38 (6 Suppl 1):I1–6.

Health Disparities Collaboratives. 2002. “Health Disparities Collaboratives.” Online. Available at http://www.healthdisparities.net/ [accessed June 4, 2002].

Kizer, K.W., J.G.Demakis, and J.R.Feussner. 2000. Reinventing VA health care: Systematizing quality improvement and quality innovation. Med Care38 (6 Suppl 1):I7–16.

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. 2002. “Introduction to MEPS Data and Publications.” Online. Available at http://www.meps.ahcpr.gov/Data_Public.htm [accessed June 4, 2002].

Michaud, C.M., C.J.Murray, and B.R.Bloom. 2001. Burden of disease: Implications for future research. JAMA285 (5):535–9.

Murray, C.J., and A.D.Lopez. 1996. Evidence-based health policy: Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science274 (5288):740–3.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. 2002. State of Health Care Quality Report. Washington, DC: NCQA.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). 1997. “Setting Research Priorities at the National Institutes of Health.” Online. Available at http://www.nih.gov/news/ResPriority/priority.htm [accessed June 4, 2002].

Partnership for Prevention. 2002. Prevention Priorities: A Health Plan’s Guide to the Highest Value Preventive Health Services.

Stevens, D.M.2002. Changing Practice/Changing Lives.Presented at May 9–10, 2002 Priority Areas for Quality Improvement Meeting.