5

Community Health and Uninsurance

Discussion of the evidence in previous chapters about community effects on access to care and on the economic and social foundations of local communities suggests that the health of the community itself may be compromised. The Committee hypothesizes that this may result from both the burden of disease related to the poorer health of uninsured community members and from spillover effects that can affect the insured as well as the uninsured. The mechanisms for this result can be as diverse as the spread of communicable diseases from unvaccinated or ill individuals and the paucity or loss of primary care service capacity as a result of physicians’ location decisions, cutbacks in clinic staffing and hours, or outright closures, as described in previous chapters. Although it is easier to detect the impacts of high uninsurance on a community’s health care providers and resources than on the health of a community’s population, community-wide health effects can be inferred from studies of access, utilization, and disease incidence.

The intentional dispersal of anthrax through the U.S. mail in late 2001 revealed yet another way in which uninsurance could threaten community health, when the impaired access to care of uninsured persons means delays in detecting, treating, and monitoring the transmission of infectious disease linked to bioterrorism (Wynia and Gostin, 2002; IOM, forthcoming 2003). As public and policy attention turned to the country’s readiness to respond to bioterrorist threats, the weaknesses of the highly fragmented public and private health care systems became apparent. This fragmentation and minimal capacity for communication across systems and types of care hamper the ability of a community to respond rapidly and effectively to an unfamiliar threat to the public’s health.

As described in Chapter 3, community uninsurance is likely to lessen access to hospital emergency medical services for all members of a community, as one of

several factors contributing to overcrowding and the diminished capacity of emergency departments (EDs) to absorb a sudden and large increase in the number of patients (U.S. Congress, 2001). This capability is key to a community’s ability to respond to emergencies such as mass casualty events and certain types of biological and chemical terrorism (IOM, forthcoming 2003). As will be described in the pages that follow, unin-surance is also hypothesized to result in greater financial strains on state and local health departments, strains that may lead to the shifting of discretionary funds from population-based public health activities to the delivery of personal health services and cost-cutting measures such as the trimming of staff. Both types of responses weaken the ability of local health departments to respond to emergencies, particularly involving the spread of communicable diseases.

The case of the bioterrorism agent smallpox, a severe and often fatal infectious disease, illustrates how uninsurance may contribute to current weaknesses in emergency preparedness. Untreated, smallpox has a 30 percent or greater case-fatality rate among unvaccinated persons (Henderson et al., 1999). It can be spread through mass public exposure to aerosolized variola virus, by close personal contact and by contact with infected material (e.g., clothing). A person becomes infectious days after exposure to the virus, when rash, high fever, and other symptoms develop. Routine vaccination of the U.S. population ceased in 1972. Thirty years later, younger members of the population are likely not to have been vaccinated, and the long-term effectiveness of the vaccinations given before 1972 is unknown. The spread of smallpox can be checked through isolation of infected persons, if they are diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion, or through vaccination (Henderson et al., 1999). A mass vaccination campaign, whether in anticipation of or in response to the detection of a smallpox outbreak, would require staff and budget resources devoted to population-based public health activities. This would include the coordination of information, resources, and personnel across the health care sector, epidemiological surveillance and investigation of suspected or reported cases, laboratory testing of samples and medical supplies, and the training of staff to administer vaccines, track after-effects, and provide information to the public (Henderson et al., 1999; IOM, forthcoming 2003). While to date, limited federal funds have been made available to the states to assist in preparing for smallpox vaccination campaigns, it is anticipated that state and local health departments may have to reallocate funds from other programs in order to support vaccination (Connolly, 2002; Altman and O’Connor, 2003).

This chapter explores the implications for population health that flow from the Committee’s hypothesis about community effects. Previous chapters describe both empirically confirmed and hypothesized effects of uninsurance on health care services, institutions, and resources and on communities’ social and economic resources more broadly. In this chapter, the Committee traces these consequences through to their impact on the health of the community.

To understand the influence of uninsured populations on community health, it is more informative, yet more difficult, to examine cities and counties rather than states or regions. While marked local variation makes detection of hypoth

esized community effects more likely, uninsured rates and measures of health status are more readily available at the state level, where local variation tends to average out and health measures are often too crude to detect meaningful associations. While regional differences in health status across the United States are closely related to differences in demographic profiles and socioeconomic circumstances, the role of community uninsurance as a factor in this relationship has not been directly evaluated. In this chapter, the Committee reviews research that addresses the relationship between community uninsurance and population-level measures of access to and utilization of services. It also presents community-level (e.g., county or metropolitan statistical area [MSA]) data for the incidence of selected conditions and health outcome measures that merit further investigation.

This chapter has four sections. The first section examines the greater burden of disease and poorer health status in areas with relatively high uninsured rates and relatively low incomes. The second section considers the interrelationships between the capacity and performance of local public health agencies both in population health activities and as providers of last resort to medically indigent community residents. In the third and fourth sections, the Committee poses questions for further research to advance understanding of the relationships between uninsurance and a variety of measures and indicators of population health and provides a summary of the chapter.

GEOGRAPHIC AND SOCIOECONOMIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH

Finding: Measured across states and metropolitan areas, persons from lower-income families, nearly one-third of whom are uninsured, are more likely to report fair or poor health status in areas with high uninsured rates.

Finding: Hospitalization rates for conditions amenable to early treatment on an ambulatory basis are higher in communities that include greater proportions of lower-income and uninsured residents, indicating both access problems and greater severity of illness.

Community uninsurance rates converge with a number of other factors that affect access to care and health status, such as the proportion of the population that is lower income and the proportion that consists of racial and ethnic minorities (Shi, 2000, 2001; IOM, 2001a, 2002a). Having a lower family income is consistently correlated with being uninsured (IOM, 2001a). About one-third (30.6 percent) of persons under age 65 in families earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are estimated to have been uninsured in 2001, over double the uninsured rate for the general population under age 65 (Fronstin, 2002). The relationship between family income and coverage is seen in the aggregate as well, in comparisons of poverty and uninsured rates among geo-

graphic regions (IOM, 2001a). Whereas having public health insurance coverage is most strongly correlated with both bad health and low income (since many adults gain Medicaid coverage because they are disabled or medically needy), uninsured persons on average have worse health status than do those with private coverage (IOM, 2002a). The variations in family income across geographic areas are also correlated with population-level measures of health and health outcomes such as having a regular source of care or hospitalization for conditions amenable to treatment on an outpatient basis.

In this section, the Committee explores the hypothesis that uninsurance affects a community’s burden of disease. The independent influence or contribution of the local uninsured rate to the health status of insured residents is an important part of this story, yet one that has been insufficiently documented and tested. The studies that the Committee reviews in the discussion that follows do not include analytic adjustments allowing distinctions to be made among the relative influence on health-related outcomes of coverage status, income level, and other major covariates of uninsured rate. While the studies do not allow for the tracing of a definitive pathway for community effects, the Committee finds that the sheer number of uninsured persons in an area adds to the overall burden of disease and disability, as measured by self-reported health status and the number of preventable hospitalizations.

Geographic differences in self-reported health status across the states correlate with state uninsured rates (Holahan, 2002). It is not possible to conclude from such macro-level, cross-sectional statistics that high uninsured rates lead to poorer health. However, the worse measures of health in states with higher levels of uninsurance suggest unmet health care needs. Among 13 states surveyed in 1999, an unadjusted comparison indicates that children and adults in lower-income families (less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level [FPL]) are more likely to report fair or poor health status in states with higher uninsured rates, compared to lower-income children and adults in states with lower uninsured rates (Holahan, 2002). For lower-income children, whose overall average for fair or poor health is reported to be 8 percent, there is a range from a high of 12 percent for Texas (38 percent uninsured rate for lower-income children) and a low of 4 percent for Massachusetts (with its 15 percent uninsured rate for lower-income children).1 For lower-income adults (under age 65), the overall average for self-reported fair or poor health status is 24 percent, ranging from a high of 27 percent for Texas (52 percent uninsured rate for lower-income adults) to a low of 16 percent for Wisconsin (33 percent uninsured rate for lower-income adults). State-level uninsured rates also correlate highly with the proportion of lower-income children and

adults who do not have a usual source of care, a measure of access (IOM, 2002a, 2002b).

For urban, suburban, and nonmetropolitan communities across the country, uninsured rates also correlate with the relative health status reported by residents. A nationally representative survey of 60 communities (a stratified, random sample of counties and groups of counties, data for 1996–1997) finds that, unadjusted for the multiple covariates of uninsured rate, residents of the 12 sites with the highest uninsured rates (average of 23 percent) are significantly less likely to report excellent or very good health (64.7 percent) and more likely to report being in good, fair, or poor health, compared to residents of the 12 sites with the lowest uninsured rates (average of 9 percent), where 73.5 percent report excellent or very good health (Cunningham and Ginsburg, 2001).

Health services researchers have proposed that potentially avoidable hospitalizations (sometimes described as ambulatory care-sensitive conditions) serve as an indicator of adequate access to primary and regular health care (Weissman et al., 1992; Billings et al., 1993, 1996; Millman, 1993; Bindman et al., 1995; Pappas et al., 1997; Gaskin and Hoffman, 2000; Falik et al., 2001; Kozak et al., 2001; IOM, 2002a, 2002b).2 However, area-wide rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations also measure the acuity of illness experienced within a population and reflect the efficiency with which health care is provided to the population as a whole. To the extent that the fraction of these hospitalizations that could have been avoided with earlier and appropriate care can be identified, the excess burden of illness (and excess costs of care) within the community can also be estimated.

Uninsured patients are more likely to experience avoidable hospitalizations than are privately insured patients when measured as the proportion of all hospitalizations (Pappas et al., 1997). Nationally, the proportion of hospitalizations that were potentially avoidable for persons younger than 65 has grown more substantially over the past two decades for uninsured persons than for those with Medicaid or private insurance, from 5.1 percent to 11.6 percent between 1980 and 1998 for the uninsured, compared with increases for Medicaid enrollees from 7.0 to 9.8 percent and for those with private insurance from 4.1 to 7.5 percent (Kozak et al., 2001).

Using ZIP-code area data to measure the proportion of lower-income residents and rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations, studies consistently report substantially higher rates of these hospitalizations in lower-income areas (Billings et al., 1993, 1996; Millman, 1993; Bindman et al., 1995; Pappas et al., 1997).

Uninsurance is likely to contribute to these higher rates. One study, encompassing 164 ZIP-code areas in New York City, finds that age- and sex- adjusted rates of hospitalization for persons younger than 65 for asthma, congestive heart failure, diabetes, and pneumonia were five to six times higher in low-income areas (where more than 60 percent of the population had household incomes under $15,000) than in high-income areas (where less than 17.5 percent of the population had household incomes under $15,000) (Billings et al., 1993). A second study performed a similar analysis for 18 MSAs, 15 in the United States and 3 in Ontario, Canada. This analysis reveals disparities in rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations within U.S. metropolitan areas that were from 200 to more than 300 percent greater in low-income ZIP-code areas than in high-income areas. In contrast, the disparities within Canadian metropolitan areas were much lower (rates for the three metropolitan areas were 40 to 60 percent greater in low-income as compared high-income local areas) (Billings et al., 1996). The authors attribute the difference in experience between U.S. and Canadian metropolitan areas in part to the greater financial access of lower-income residents to primary and ambulatory care available under the Canadian health care system.

A third national study examines rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations (adjusted for age and sex) in relation to median income within ZIP-code areas (Pappas et al., 1997). The authors estimate that designated conditions accounted for between 3 million and 5 million hospitalizations in 1990 (12 to 19 percent of all hospitalizations in that year, excluding those related to childbirth and for psychiatric conditions); see footnote 2 for a list of these conditions. They used the rates of hospitalization for these designated conditions that residents in areas with the highest median household incomes ($40,000 or more) experienced as the baseline rates below which such hospitalizations could not be reduced. The authors then calculated that almost 30 percent of such hospitalizations (between 844,000 and 1.4 million) could represent excessive prevalence and severity of illness within lower-income neighborhoods.

The higher hospitalization rates for conditions that can be managed on an outpatient basis (if access to and quality of care are good) that occur in communities with proportionately more uninsured and lower-income residents highlight the costliness of uninsurance in terms of dollars as well as health. Individual suffering and disability could be avoided with greater access to appropriate ambulatory care services. In addition, timely and adequate care for uninsured residents could lead to offsetting reductions in the demands on the resources of community facilities and public budgets that currently provide hospital care.

PUBLIC HEALTH AND COMMUNITY UNINSURANCE

Finding: Because areas with relatively high uninsured rates are likely to have greater burdens of disability and disease, their needs for

population-based public health services are expected to be greater and the accompanying financial pressures on state and local health departments considerable.

Finding: State and local public health programs are adversely affected when funds are diverted to support personal health services for uninsured persons. Budgets for population-based public health activities, such as disease and immunization surveillance, community-based health education and behavioral interventions, and environmental health, which benefit all members of a community, frequently are squeezed by demands on health departments to provide or pay for safety net services for the uninsured.

Finding: The transformation of public health agencies into assurers rather than providers of health services is likely to leave uninsured members of the community disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to the receipt of privatized services.

Public health, as practiced by health departments, includes the key functions of assessing population health, developing policy solutions for problems identified, and ensuring that problems are addressed by the solutions devised (IOM, 1988). Many health departments also care for uninsured residents who have difficulty gaining access to care in other settings. About a third of local health departments surveyed in the early 1990s reported that they offered general primary care services (NACCHO, 2001). A more recent survey finds that more than one-quarter of local health departments serve as the only safety-net provider in their community (Keane et al., 2001a)

The national consensus-based planning document Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2000) identifies ensuring access to personal health services as one of ten essential activities of health departments. Particularly in rural areas, health departments can be central sites for the delivery of personal health services, even though many rural counties do not have fully staffed public health departments and may not offer much in the way of health services (NACCHO, 2001). Yet health departments do much more than fill in some of the many gaps in the U.S. personal health care delivery system, and public health involves much more than the provision of health services to uninsured people.

Historically, there have been tensions between the public health and medical care professionals and constituencies over the relative shares of resources devoted to population-based health-oriented activities (e.g., injury prevention) on the one hand and the provision of health services to members of medically underserved groups, including uninsured persons, on the other (IOM, 1988, forthcoming 2003; Baker et al., 1994). In many parts of the country, health department officials have expressed their perceptions of being caught between the increasing demand and need for care of growing numbers of uninsured persons and diminished

budgets (IOM, 1988; Lewin and Altman, 2000). These pressures are felt not only within health departments but also by other providers in the health care system (see Chapter 2 for further discussion).

In the 1990s, these tensions were sharpened by the privatization of services and functions at many health departments, a development brought about by the advent of Medicaid managed care contracting by many states and by local health departments seeking greater cost-effectiveness and efficiencies through contracting for personal health services delivery (Goldberg, 1998; Martinez and Closter, 1998; Keane et al., 2001c; Mays et al., 2001).

The transition of state Medicaid programs from fee for service to managed care contracting has added financial pressures on health departments, pressures that may result in decreased access to health department services for all members of a community (Koeze, 1994; Ormond et al., 2000a). Local health departments have experienced losses of revenue when Medicaid enrollees have been assigned for care to private health plans or networks for care that do not include the health department. They have tended to receive less favorable reimbursement than under fee-for-service arrangements and have had diminished capacity to support the delivery of personal health services to uninsured persons as a result (Goldberg, 1998; Martinez and Closter, 1998). For example, through the 1980s, Medicaid reimbursement for immunizations and screening and health assessment services (under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment [EPSDT] program) was an important revenue source for local health departments delivering well-child care to all of their clients, uninsured as well as Medicaid beneficiaries (Martinez and Closter, 1998; Slifkin et al., 2000). In response to the infusion of federal Medicaid dollars for these services during the 1980s, states cut back or simply did not increase their direct support of health department activities. With the loss in the 1990s of fee-for-service reimbursements for these health department services consequent to Medicaid managed care contracts with private health plans for EPSDT services, together with cuts in real-dollar terms in their budgets, local health departments have been pressed to reduce their level of service provision (Ormond and Lutzky, 2001; IOM, forthcoming 2003).

In an effort to improve cost-effectiveness and quality of care, many health departments have privatized the delivery of certain personal health services (Keane et al., 2001b, 2001c).3 Many services that were once delivered predominantly in public health clinic settings—for example, immunizations and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and tuberculosis (TB)—are or can be delivered effectively within other primary care settings. For example, as both childhood and adult immunization services have been integrated into private and public health

insurance plans, the role of local health departments in directly providing immunizations in special clinics and campaigns has shifted to quality assurance in private practitioners’ offices and in health plans, surveillance of immunization rates, and the promotion of professional best practices among private plans and practitioners (Slifkin et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000).4

With this privatization has come the growth of health departments’ roles as assurers of population health, rather than as direct service providers themselves, with an expanded role for states and localities in overseeing and facilitating the delivery of population-based public health services within private health plans (IOM, 2000, forthcoming 2003). However, for uninsured individuals, a shift to private sector primary care and the loss of dedicated public health sites for care may result in diminished access to this care because private practitioners and especially health plan services may not be readily accessible to the uninsured. A survey of a random sample of local health department directors, stratified by the size of their jurisdiction, finds that a majority believe that their uninsured constituents cannot rely on privatized services alone and that the directors do not see themselves as able to promote quality of or access to care for privatized services (Keane et al., 2001a). Thus, the transformation of public health agencies into assurers rather than providers of health services is likely to leave the uninsured within the community out of the equation and disproportionately disadvantaged with respect to the receipt of privatized services.

The Committee hypothesizes that health departments have often tried to address the unmet health needs of a sizable or growing uninsured population by shifting discretionary funds toward the delivery of health services at the expense of population-based public health programs (e.g., injury control, disease surveillance, environmental health) and that this shifting, absent new revenue sources to finance care delivery, is likely to have adverse effects on the community. The Committee bases its thinking on the conclusions of two Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committees that have evaluated the status of public health, one from the vantage point of the 1980s and the other more recently (forthcoming 2003). Both reach similar conclusions, based on site visits and interviews with public health officials as well as on a limited research literature.

-

According to the IOM Committee on the Future of Public Health, “the direct provision by health departments of personal health care to patients who are unwanted by the private sector absorbs so much of the limited resources available to public health—money, human resources, energy, time, and attention—that the price is higher than it appears. Maintenance functions—those community-wide public services that are truly ill-suited to the private sector—become stunted

-

because they cannot compete, and key functions such as assessment and policy development wither because they are not seen as life-and-death matters.” (IOM, 1988, p. 52).

-

The IOM Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century, in its recent report states: “The committee finds that as in 1988, the continued lack of a nationwide strategy to assure adequate financing of personal medical, preventive, and health promotion services will continue to place undue burdens on the public health system and to fragment the provision of personal health services to those most in need of comprehensive, integrated approaches. Also, if the number of uninsured continues to increase, this may require the diversion of resources urgently needed for population health efforts to the health care assurance component of the governmental public health system” (IOM, forthcoming 2003, p. 154).

Vaccine-Preventable and Communicable Disease

Finding: The strength of the local health department and the adequacy of its funding are likely to influence how community uninsurance affects the health of all community members. The incidence and prevalence of vaccine-preventable and communicable diseases are expected to be higher in areas with high uninsured rates where health departments have been chronically short of funding.

In the following discussion of childhood immunization and communicable diseases (including STDs, HIV/AIDS, and TB), the Committee examines how public health efforts in these areas are affected by and related to uninsurance within communities. The examples of childhood immunization rates and reportable conditions illustrate how the concentration of ill health in areas with higher uninsured rates may be amplified by these high rates. Despite the decline in the incidence of many infectious diseases in urban and suburban areas over the past decade (Andrulis et al., 2002), these conditions are common in communities facing other challenges related to the lower socioeconomic status of their residents, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Likewise, despite national and state public health efforts to maintain high levels of childhood immunizations, these rates also vary substantially among communities and are lower in lower-income urban counties and areas with less health insurance coverage (Santoli et al., 2000).

Communicable disease control is a traditional core function of health departments, to prevent their spread throughout the population, for example, through the tracing and notification of persons with whom an infected individual has come in contact. For both immunization rates and communicable diseases, the health consequences of uninsurance are intertwined with the long-term underfunding of health departments, which traditionally have led in managing immunization programs and detecting and treating communicable diseases. The Committee hypothesizes that the presence of sizable uninsured populations that do not have

reliable access to services provided either by health departments or by practitioners in the private sector means that both population immunization levels and communicable disease rates are likely to be worse than they otherwise would be if everyone in the United States had health insurance.

The section that follows includes illustrative discussions of potential population health effects of uninsurance related to childhood immunization levels, STDs (syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia), and TB, diseases that are both preventable and curable if diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion. The incidence and prevalence of these diseases reflect the level of public resources devoted to prevention, screening, contact tracing, and successful treatment. HIV/AIDS is an important part of the story (e.g., syphilis and gonorrhea leave a person more vulnerable to HIV infection, and HIV-positive persons are more likely to contract TB) and is also discussed below.

Immunization Rates

Underimmunization increases the vulnerability of entire communities to outbreaks of diseases such as measles, pertussis (whooping cough), and rubella (IOM, 2000). The history of childhood immunization and federal immunization policy since the development of the polio vaccine in the 1950s has been one of cyclical efforts and sporadic attention (Johnson et al., 2000; Roper, 2000; Smith, 2000). When attention to this public health issue wanes, outbreaks occur. The latest and deadliest major outbreak of measles occurred between 1989 and 1991 in several major U.S. cities, including Chicago, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and Washington, D.C. (Johnson et al., 2000). During 1989 and 1990, a total of 43,000 cases of measles were reported and more than 100 deaths were attributed to this disease (IOM, 2000; see Box 5.1).

Local, state, and federal public health agencies and programs have as central missions ensuring full immunization coverage of the nation’s children for a range of childhood illnesses and promoting the immunization of adults for influenza, pneumonia, and other diseases (IOM, 2000). These goals depend in ever-greater measure upon immunization within health insurance programs such as Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), employment-sponsored plans, and Medicare (DeBuono, 2000; Fairbrother et al., 2000; Sisk, 2000). As a result, both childhood and adult immunization levels are positively correlated with having either public or private health insurance as compared with being uninsured.

The completely federally financed Vaccines for Children (VFC) program provides childhood vaccines free to private primary care practitioners, federally qualified health centers, and public clinics for administration to uninsured children, Medicaid-eligible children, and in clinical settings, children whose private insurance does not cover immunizations (IOM, 2000). Established in 1994, this program provides vaccines to about one-third of all children in the United States between birth and age 18 (CDC, 2002b). Notably, VFC is the Centers for Disease

|

BOX 5.1 In 1983, a record low number of measles cases was reported in the United States, 1,497 cases. This was a reduction of 97 percent from the more than 57,000 cases reported in 1977. (A vaccine for measles became widely available in 1965.) This success was not sustained, however. In 1984 and 1985, outbreaks occurred among older children who had entered school before the vaccine was routinely used. In 1986, a new pattern emerged, with outbreaks among preschool children, concentrated in inner city, low-income neighborhoods in 20 counties across the United States. These sporadic outbreaks of measles became epidemic between 1989 and 1991. Unimmunized and underimmunized preschoolers became a reservoir for the disease, which spread rapidly through several cities, including Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New York, and Washington, D.C. Within two years, 43,000 cases of measles were reported and 101 deaths were attributed to the disease. The measles epidemic led to the creation of a federal Interagency Coordinating Committee in 1991 to improve access to immunization services and to the federal Infant Immunization Initiative in 1992. It also provided impetus for the passage of the VFC program as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 to reduce financial barriers for private practitioners to administer, and thus for children to receive, immunizations. SOURCE: IOM, 2000. |

Control and Prevention’s (CDC) largest public–private partnership, reaching children through arrangements with 33,000 private practice sites (primarily physicians’ offices) and 10,000 public clinics (CDC, 2002b). By making free vaccines available to physicians in private practice for administration to uninsured and Medicaid-enrolled children, the VFC program keeps children in their medical homes for immunizations and avoids fragmentation of their care by eliminating the need to make referrals to public immunization clinics.

Although VFC is an important programmatic improvement in securing the immunization of uninsured children, achieving childhood immunization goals is facilitated when children have public or private health insurance. Insurance increases the likelihood that children will have a regular source of care and receive routine preventive services (IOM, 2002b). When New York State expanded children’s insurance prior to the enactment of SCHIP, the statewide immunization rate rose from 83 to 88 percent for all children between 1 and 5 years of age (Rodewald et al., 1997). The increase was greatest among those children that had been uninsured and those who had had a recent gap in coverage of longer than six months. At the same time, immunization visits to primary care practitioners’ offices increased by 27 percent and those to public health department immunization clinics decreased by 67 percent (Rodewald et al., 1997).

Despite the efforts of the past decade to expand sources of federal financial support for childhood immunization services in children’s medical homes, the 8.5 million children who currently do not have health insurance (Mills, 2002) are at increased risk of not receiving immunizations. Because uninsured families and children tend to live in neighborhoods with higher-than-average uninsured rates and are likely to go without immunizations, influenced by a host of related factors such as lower family income and lower parental educational attainment, all who live in these communities are more likely to be exposed to disease outbreaks such as the ones that culminated in the measles epidemic of 1989–1991. Because a community’s level of childhood immunization is influenced by many factors that vary along with uninsurance rates (e.g., family income) and also by the scope and effectiveness of the local public immunization program, direct links between uninsurance and immunization levels are difficult to evaluate statistically. As an illustration of the general relationship, however, Table C.5 (Appendix C) displays the relative rankings of 28 metropolitan counties on up-to-date immunization rates for 2-year-olds for a basic series of four vaccines and on uninsured rates. Data are for 1997.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases are not confined to uninsured persons, but because uninsured persons are less likely to receive a timely diagnosis or treatment, the consequences can be particularly severe (IOM, 2002a). The Committee hypothesizes that these consequences may include continued transmission of the disease to other members of the community. Like many other conditions, STDs are more common among lower-income persons, and the extent to which they are diagnosed and treated depends on the capacity and responsiveness of community providers in serving such patients (IOM, 1997; CDC, 2000). Often, local health departments operate clinics devoted to STDs and their clientele tends to be uninsured persons (Landry and Forrest, 1996; Celum et al., 1997). If funding for local health department specialty services (e.g., STD clinics, family planning) is reduced because of mandated priorities or when other claims on public budgets take precedence (such as the state share of Medicaid program costs or public hospital operations), STDs may go undetected and untreated and their incidence and prevalence in the community at large may increase. Syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, three of the most serious and common STDs, are bacterial infections that are treatable with antibiotics once diagnosed (CDC, 2000). See Boxes 5.2, 5.3, and 5.4 for brief descriptions of these 3 diseases. If not treated, they are transmissible, so their incidence rates are indicators of the relative effectiveness of local public and personal health care services (CDC, 2000).

Although there are federal funds to support state and local programs for the diagnosis, contact tracing, and treatment of these STDs, federal grants do not meet the full need for such services. In the context of diminishing state and local funding to subsidize direct services delivery to medically indigent persons, the

|

BOX 5.2 During the 1990s the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States dropped significantly, with the number of cases reported in 2000 the lowest since record keeping began in 1941—5,979 reported cases, or a rate of 2.2 cases per 100,000 persons (CDC, 2001c; Lukehart and Holmes, 1998). This chronic, systemic infection is most often transmitted sexually, although it may also be conveyed nonsexually and in utero as congenital syphilis (Lukehart and Holmes, 1998). When it first appears, it can be treated with antibiotics. If untreated, it will become latent and later develop into secondary and tertiary forms with an array of severe adverse health outcomes (CDC, 2001c). Tracing, informing, and treating the partners of persons with infectious syphilis are critical to preventing spread of the disease because about 50 percent of all sexual partners of a person with infectious syphilis become infected themselves. The disease can be detected by screening during pregnancy (Lukehart and Holmes, 1998). Despite the declining incidence of syphilis nationally, the South remains the epicenter for this STD, particularly in urban and suburban areas, and African Americans as a group in this region continue to be disproportionately affected—a pattern reflecting the influence of demographic and socioeconomic circumstances and difficulties gaining access to health care (CDC, 2001c; Andrulis et al., 2002). Syphilis is also known to facilitate transmission of the virus that causes AIDS (Lukehart and Holmes, 1998). In 1999, the federal government began a national campaign to eradicate syphilis entirely. |

|

BOX 5.3 Gonorrhea is the most common of the reportable deseases in the United States, with a stable case rate in recent years of about 132 cases per 100,000 persons (Holmes and Morse, 1998). Patterns of incidence for gonorrhea resemble those for syphilis. There are marked ethnic and racial disparities, although, as with syphilis, biases tied to reporting from public clinics may overstate the degree of these differences. Reported rates range from 28 per 100,000 persons for non-Hispanic whites and 70 per 100,000 persons for Hispanics to 827 per 100,000 persons for African Americans (Holmes and Morse, 1998). In addition, youth, single marital status, and low socioeconomic status are each associated with greater likelihood of getting gonorrhea. While the incidence and prevalence of this STD reflect the presence of sexual and health-related behavioral risk factors, they also serve as indicators of local access to care (Holmes and Morse, 1998). Once transmitted, gonorrhea can become infectious within days and not exhibit symptoms. Public health outreach, interviews, and contact tracing must be carried out quickly if they are to be effective in preventing the spread of disease. Treatment is relatively inexpensive and may be as simple as one dose or a short course of antibiotics (CDC, 2001c). Incompletely treated, gonorrhea strains may mutate into drug-resistant versions. It is estimated that one-third of the strains found in the United States are resistant to penicillin or tetracycline, two common antibiotics used to treat this infection (Holmes and Morse, 1998). |

|

BOX 5.4 Chlamydia is frequently hard to detect, with an estimated incidence of 3 million cases annually, of which just one-sixth are reported (CDC, 2001a). This bacterial infection is easily treated and cured, when diagnosed. Untreated, it can cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, and tubal pregnancies. As many as 40 percent of women with untreated chlamydial infections develop PID, which in turn is related to infertility and chronic severe pelvic pain. Women infected with chlamydia are at much higher risk (three to five times greater than those not infected) of acquiring HIV infection. Because of its prevalence and the fact that 75 percent of the women and 50 percent of the men infected with chlamydia have no symptoms, screening is the most effective approach to controlling this disease. Adolescent girls between 15 and 19 years of age account for 46 percent of reported infections, and women ages 20 to 24 account for another 33 percent (CDC, 2001a). The CDC recommends screening all sexually active girls and women under 20 years of age at least annually, and annual screening of women 20 years and older who have one or more risk factors for chlamydia (e.g., new or multiple sex partners, lack of barrier contraception). Within the past decade, a collaborative federal prevention program has established demonstration projects across the United States that involve family planning providers, STD and primary health care programs, and public health laboratories to provide screening and treatment services. However, given the large at-risk population, targeted screening programs cannot control the spread of this disease. Screening and treatment within primary care programs and health plans present greater opportunities to address this health problem. One randomized trial of chlamydia screening and treatment in a health maintenance organization achieved a 56 percent reduction in the incidence of PID among the screened group within a year of the screening (CDC, 2001a). |

IOM report The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases also concludes that there is a need for “a secure source of funding for STD-related services for uninsured persons,” including federal categorical support, to maintain and improve on national progress in stemming the prevalence of STDs (Eng and Butler, 1997). State and local governments pay for clinical services, contributing a little more than half (58 percent) of the operating funds for specialized STD clinics, with much variation among localities (Eng and Butler, 1997). The Committee posits that because uninsured persons are less likely to gain access to private sector health services, they are also more likely to have undetected or untreated STDs and, as a result, may be more likely to infect someone else.

For uninsured persons, the key site of care for STDs is the local health department STD clinic. Other sites for care include other community-based clinics (e.g., community health centers, family planning clinics, school health centers), private physician offices, and hospitals (Landry and Forrest, 1996). Public STD clinics are found in most counties and cities and in every major city and every

state. The size of these clinics, the services provided, the quality of care, and the funding streams that support these clinics vary considerably from location to location (Eng and Butler, 1997). STD clinics function in a safety-net capacity, providing a high volume of care and much of the specialized care (e.g., screening, contact tracing and notification of partners who may have been infected by a patient, short-term treatment) for these diseases nationally and serving patients who seek privacy or have difficulties gaining access to care because they are uninsured or because there are no knowledgeable local providers (Eng and Butler, 1997). Clients’ access to STD clinic services is more often limited by clinic capacity than by the price of services, as sliding-scale payment arrangements are common and patients pay little or none of the costs of care (Eng and Butler, 1997).

A 1995 survey of five urban STD clinics around the country found that clinic clients are likely to be uninsured (58 percent), under 25 years of age (51 percent), members of ethnic and racial minority groups (64 percent), less well educated (55 percent with a high school diploma or fewer years of schooling), and low income (67 percent earning less than $20,000 a year) (Celum et al., 1997). Symptoms of an STD were most likely to be the motivator to visit the clinic, followed by concerns about the cost of care. Fully 66 percent of those surveyed were diagnosed with an STD as a result of their visit (Celum et al., 1997). Data on funding and services provided at public STD clinics and other community clinics that offer STD-related services are limited, and even less is known about experiences in the private sector, where the majority of STD cases are diagnosed (Eng and Butler, 1997).

A recent IOM study points to the lack of coordination among providers and institutions serving a common population and the importance of coordination in both cities (where STD clinics have very high caseloads) and rural areas (where clinics may have limited hours or services due to lower demand or fewer funds) (Eng and Butler, 1997). The fragmented and unstable nature of public funding and lack of coordination in the provision of STD services particularly affect uninsured populations that disproportionately rely on public clinic services. Poorly coordinated care can lead to incomplete treatment or no treatment (Eng and Butler, 1997). Lack of health insurance coverage may mean that an insured partner receives treatment while an uninsured partner does not. The relationship between lack of access to care and continued infectiousness among persons with syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia is clear. The Committee hypothesizes that community uninsurance, coupled with lack of public resources to pay for or deliver coordinated STD services, may contribute indirectly to the spread of disease within the community.

HIV/AIDS

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) constitutes an ongoing global epidemic. In 2000, an estimated 800,000 to 900,000 people in the United States were living with HIV infection or AIDS, the more advanced form

of the infection (CDC, 2001c). Almost 20 percent of all persons with HIV infection are uninsured (Kates and Sorian, 2000). Persons who are HIV positive and uninsured are more likely to be unaware of their infectious state than are seropositive persons with health insurance, either public or private (Bozzette et al., 1998). As a result, one health consequence of community uninsurance may be a greater risk of the transmission of the virus that causes HIV/AIDS especially for members of groups that are already at greater risk for becoming infected (e.g., persons from lower-income families or households, members of ethnic and racial minority groups, injection drug users).

The Committee’s second report, Care Without Coverage, documents numerous adverse health consequences for uninsured adults who are HIV positive, including greater morbidity and mortality (IOM, 2002a). These findings reflect the greater difficulties that uninsured persons have in obtaining access to health services, a regular source of care, and quality care that meets professional and clinical standards (IOM, 2002a).

-

Uninsured adults are less likely to receive primary and preventive services that include screening.

-

They are much less likely to receive the combination antiretroviral therapy, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), with either protease inhibitors or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, that is the clinical standard of care for HIV/AIDS (HIV/AIDS Treatment Information Service, 2002).

-

They are likely to experience greater delays in starting treatment after having been diagnosed, as measured by a first office visit and waiting time until the start of antiretroviral therapy.

-

They are less likely to receive the regular care that is integral to the clinical standard of care for HIV/AIDS, are less likely to receive needed health services, and are more likely to stop drug therapy.

While part of the difficulty in gaining access to timely and appropriate care is linked to the site of care for uninsured patients (Sorvillo et al., 1999), another aspect of the problem is the difficulty that uninsured persons who are HIV positive face in obtaining public coverage before they have developed full-blown AIDS (Kates and Sorian, 2000). Health insurance is a key facilitator of access to care for persons with HIV because of the cost of therapy. In recent years, lifesaving combination antiretroviral therapy has transformed HIV from a usually deadly disease into a chronic illness that may be managed over years but at a cost of roughly $20,000 annually for persons who have not yet developed AIDS (Kates and Sorian, 2000). Although uninsured persons can and do obtain care from community health centers, academic medical centers, public hospitals, and other providers that participate in safety-net arrangements, effective treatment of HIV, to lower the chances that a person will develop AIDS, requires regular care and coordination of care across providers, both of which are more difficult to do in

safety net settings, given limited funds and other resources (Kates and Sorian, 2000).

Most HIV-positive persons with Medicaid or Medicare, or other publicly subsidized coverage (e.g., through a state high-risk pool as a medically uninsurable person), have obtained this coverage only through being certified as disabled (Kates and Sorian, 2000). Medicaid coverage is available to persons who meet income and categorical eligibility standards in their state of residence, while Medicare coverage, which does not include prescription drug coverage, may be available after a 29-month waiting period (KFF, 2000). Some states have federal program waivers that allow them to provide Medicaid coverage as soon as someone is diagnosed with HIV (KFF, 2000).

Because of the existing barriers to public coverage, a particularly vulnerable group of people—uninsured persons who are HIV positive—is left at risk of not being diagnosed or adequately treated at the point at which they are most likely to transmit the virus. There are discretionary public funds for HIV care available to the states and certain designated metropolitan areas through the federal Ryan White program (Kates and Sorian, 2000). These funds are used by states and localities to fund some limited early intervention services, treatment, wraparound services (e.g., transportation, outreach, health education), and prescription drugs for uninsured and underinsured persons with HIV disease. Thus, uninsured persons may not necessarily have to rely on charity care or pay out of pocket for all expenses associated with diagnosing and treating HIV. States vary in how they use Ryan White funds, so the experiences of uninsured persons in obtaining access to screening and therapy for HIV-positive status depend on how the funds are allocated within states according to priorities set by planning councils and the state. In the case of prescription drug benefits under Title II of the Ryan White CARE Act (AIDS Drug Assistance Programs), all states participate in this program but many have waiting lists for potential enrollees (Aldrige et al., 2002).

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a preventable and treatable contagious disease whose spread may be exacerbated by uninsurance within a community. A bacterial respiratory infection that usually settles in the lungs, TB is transmitted through contact in close quarters, often by sneezing or coughing. The disease may be latent or active and is more likely to be conveyed in its active phase. For close contacts of persons with TB, the case rate is 700 per 100,000 persons (Geiter, 2000). In contrast with STDs and HIV infection, whose transmission requires intimate contact, TB is spread in public settings such as schools, workplaces, hospitals, and clinics. People may be completely unaware of their exposure to and potential for contracting the disease.

Although the incidence of TB has declined over time, it has been increasingly geographically concentrated within the largest cities (greater than 500,000 population), although prevalence data are not available consistently to compare the

experiences of specific communities (Geiter, 2000). Previously closely associated with the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and disproportionately seen in homeless persons, persons affected by substance abuse, and prison populations, in recent years TB has become more of a concern for low-income immigrant communities in urban areas, along the southwestern U.S. border with Mexico, and in other medically underserved communities (Geiter, 2000; CDC, 2001b; Kershaw, 2002). Of the 17,531 reported TB cases in the United States in 1999, 43 percent were among foreign-born persons, with people born in Mexico accounting for 1,753 cases (almost a quarter of the foreign-born cases) (CDC, 2001b).

Timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment are integral to stemming the transmissibility of tuberculosis, particularly when latent, given the relatively low number of active cases (IOM, 2000). Inadequate access to primary and follow-up care has contributed to the increase in drug-resistant tuberculosis, which poses a public health threat (CDC, 1999). This not only results in greater suffering and risks for the patient but also creates greater risks of infection for those with whom the patient comes in contact. Even more so than for STDs, the control of this disease rests with health departments and success is directly related to the adequacy and continuity of public funding. Screening, contact tracing and notification, and treatment are all labor intensive. This is particularly true for treatment, which requires up to a year’s worth of daily medication, with multiple pills taken at different times each day. To ensure compliance, the standard of care—directly observed therapy—involves a public health worker watching the patient take his or her medication (Geiter, 2000). As the number of TB cases has declined nationally, TB control programs have had to compete for public dollars that have been redirected to other health issues, even though the disease has not been eradicated (Geiter, 2000).

Immigrants from Mexico and binational U.S. residents have a greater risk of TB because of the higher rate of the disease in Mexico (CDC, 2001a). Legal immigrants seeking permanent residence are screened for infectious TB before entering the United States and may enter the country with either active but noninfectious disease or latent disease, with instructions to report to a health department at their destination for follow-up treatment (Geiter, 2000). Undocumented immigrants are unlikely to have been tested.

Immigrants to the United States are both more likely to be exposed to TB and less likely to be diagnosed and treated in a timely manner. Recent immigrants are more likely than long-term U.S. residents to encounter difficulties in gaining access to care. Their generally lower incomes and exclusion from Medicaid mean that they are much less likely to have health insurance coverage (Hudman, 2000; IOM, 2001a; Ku and Matani, 2001). Recent immigrants are at the highest risk for developing TB, and this risk declines with increasing length of stay: 30 percent of all TB cases among foreign-born persons occur in the person’s first year within the United States and 56 percent of all cases occur in the first five years (Geiter, 2000). In this way, immigrant communities with high uninsured rates can experience

tuberculosis as a spillover health consequence, and all members of the community may be exposed.

Urban areas around the United States have experienced an increase in TB case rates due to growth in the size of foreign-born populations from countries with higher rates than the United States. New York City, for example, has the highest TB rate of any city nationally, with 1,261 new cases of the disease reported in 2001. In parts of New York City, tuberculosis has made a resurgence, following a decline after HIV/AIDS-related TB was addressed in the mid-1990s (Kershaw, 2002). During the 1990s, the city saw a shift from 18 to 64 percent of new TB cases annually occurring among foreign-born residents (Kershaw, 2002). Compared to the 1992 rate of 240 cases per 100,000 persons in Central Harlem, the rate in immigrant communities is considerably lower—for example, 36 cases per 100,000 persons in the Queens neighborhood of Corona. The rate for Corona, however, is more than twice New York City’s average case rate of 16 cases per 100,000 persons and is seven times the national average.

Tuberculosis case rates are somewhat lower but no less a threat to public health along the 2,000-mile U.S.–Mexico border, where the mobility of local residents and the immigration of seasonal agricultural workers have brought greater-than-average risk for contracting TB (CDC, 2001b). The majority of TB cases reported between 1993 and 1998 were U.S.-born citizens. Persons born in Mexico, however, accounted for just over 40 percent of all cases reported in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (CDC, 2001b). The TB case rates for border cities in Texas are high. For 1998–1999, per 100,000 population, the case rates of TB were 23 in Laredo, 22 in Brownsville, 70 in Matamoros, 15 in McAllen, and 10 in El Paso, Texas (CDC, 2001b).

For the border region, higher rates of communicable and chronic diseases reflect a mix of circumstances that contribute to a lack of access to health care. Poverty rates are high, and the rapid economic and population growth has not been matched by increases in public or private health care services capacity (Pinkerton, 2002). Uninsured rates in border counties range between 25 and 35 percent and are believed to be even higher among residents of semirural colonias, where one survey put the uninsured rate at 64 percent (Pinkerton, 2002). Border hospitals that treat TB patients are at a financial disadvantage. As rural facilities, they deliver a relatively lower volume of services and receive lower payments from programs such as Medicaid, compared with urban, higher-volume hospitals. At the same time, they incur significant amounts of uncompensated care and may not receive reimbursement for nonemergency services delivered to uninsured recent immigrants, who are not eligible for Medicaid coverage (CDC, 2001b; Pinkerton, 2002). For TB patients, migratory living patterns and cultural and language differences are likely to make access to care and successful completion of treatment difficult. For border health departments, effective TB control will require greater coordination with Mexican health officers of outreach, partner notification and contact tracing, screening, and treatment (CDC, 2001b).

As is the case with childhood immunizations, multiple covariates are likely to

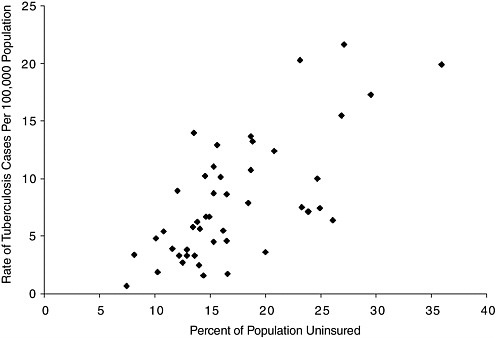

FIGURE 5.1 Urban uninsurance and tuberculosis case rates, 1997.

NOTES: Data points represent the following cities: Akron, OH; Albuquerque, NM; Atlanta, GA; Austin, TX*; Baltimore, MD; Birmingham, AL; Boston, MA*; Buffalo, NY*; Charlotte, NC*; Chicago, IL; Cincinnati, OH*; Cleveland, OH; Columbus, OH; Dallas, TX; Dayton, OH; Denver, CO; Detroit, MI; Fort Worth, TX; Houston, TX; Indianapolis, IN; Jacksonville, FL; Jersey City, NJ; Kansas City, MO*; Louisville, KY; Memphis, TN*; Miami, FL; Milwaukee, WI; Minneapolis, MN*; Nashville, TN; New Orleans, LA; New York City, NY; Newark, NJ; Norfolk, VA*; Oakland, CA; Oklahoma City, OK; Omaha, NE*; Philadelphia, PA; Phoenix, AZ*; Richmond, VA; Rochester, NY; Sacramento, CA; San Antonio, TX; San Francisco, CA; St. Louis, MO*; Tampa, FL; Tulsa, OK; and Washington, DC.*

*These cities represent multicounty areas, while disease rates are for the central county unless otherwise indicated.

SOURCES: Brown et al., 2000; CDC, 2002a.

influence the relationship between community uninsurance and TB case rates. Figure 5.1 illustrates the simple, unadjusted correlation between TB case rates and uninsured rates for 47 large MSAs (where both rates are available) for 1997. This fairly large and statistically significant correlation (Spearman coefficient = 0.63, p < .001) between reported cases of TB and uninsured rates is likely to be overstated due to the presence of unmeasured covariates with uninsured rate.5 Even if this substantial correlation does not support the conclusion that uninsurance

|

5 |

See Table C.5 in Appendix C for the uninsured and TB case rates used in this figure. |

is a major causal factor in the incidence of TB, it nonetheless indicates an increased risk for the community at large with respect to the transmission of TB.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

5.1 Health Status Within the Community at Large

Does the local uninsured rate, independent of other factors, affect the health status of community residents overall? Are particular groups within the general population more affected than others?

A number of cross-sectional studies have documented the worse health status and access to care of lower-income populations in localities and states with relatively high uninsured rates. However, these studies neither confirm nor reject the hypothesis that high rates of uninsurance locally have deleterious effects on health and access to care among those with coverage. Longitudinal studies could shed some light on this question. Do changes in the uninsured rate over time lead to changes in the health status of insured people as well as to changes in the health of those lacking coverage? Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status need to be controlled analytically in such studies, as they influence health outcomes and covary with uninsured status (IOM, 2002a; Smedley et al., 2002).

5.2 Public Health Departments and Services, Including Emergency Preparedness

Does demand for personal health care services by uninsured residents adversely affect the availability of public health services within localities and states? Does the presence of substantial uninsured populations within communities adversely affect emergency preparedness and the community’s ability to respond effectively to bioterrorism and other mass casualty events?

The Committee’s findings about the likely reduced access to hospital emergency medical services and trauma care in areas with high uninsured rates allude to a related community effect, emergency preparedness. Our nation’s capability to respond to casualties on a broad scale, including bioterrorism, is a function of its public health capacity, which depends on adequate and consistent funding for public health activities and health departments at the state and local level nationally. To the extent that uninsurance contributes to the under-funding of public health programs that perform these functions, uninsurance may weaken emergency preparedness. The influence of the presence of many uninsured people on public health preparedness and the ability of the public health programs to contain bioterrorism also need to be examined.

State and local health departments do not now offer a reliable source of information for tracking expenditures for and resources devoted to personal health care and public health services, either for insured or uninsured residents (IOM, forthcoming 2003). The issue of states’ allocations of federal and own-source health dollars between public health activities and personal health services merits

closer and regular evaluation. To do this would require more systematic and standardized accounting and reporting of state and local health spending than currently exists (IOM, 2000, forthcoming 2003). In view of the increasing demands being placed upon state and local health departments in the areas of emergency preparedness and disease surveillance in the context of bioterrorism, the need for such information is urgent.

5.2 Population Health (Burden of Disease), Including Spillover Effects of Com municable and Chronic Diseases

Does the local uninsured rate, independent of other factors, influence the spread or prevalence of communicable diseases?

The lack of information relating local health insurance coverage rates to health indicators precludes definitive statements about the effects of uninsurance on population health. Have preventable infectious disease rates declined in communities that have substantially reduced the number of uninsured? How concentrated or diffused are the spillover effects on population health of uninsurance within the community? Are those who are affected similar to the uninsured population on several social, geographic, or economic dimensions, or is population health widely affected throughout the community?

Surveys and statistics that report on both health insurance and health status at the county, city, and neighborhood levels are needed. In order to assess the effects of relatively low coverage rates on the incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis, HIV disease, and other STDs, for example, one must know local uninsured rates as well as the case rates for at-risk populations at the county and city levels. Any direct relationship cannot be detected with the aggregate statistics for STD case rates and for uninsured rate that are now available.

Chronic diseases can also have spillover effects, and their exacerbation by lack of health insurance has not been examined. For example, research on the interaction of severe mental illness and uninsurance could lead to a better understanding of the social and economic, as well as the health-related, costs that result. In Care Without Coverage, the Committee reports that nearly 20 percent of adults with severe mental illnesses are uninsured and as a result are less likely than insured adults to receive appropriate care (McAlpine and Mechanic, 2000; IOM, 2002a). One example of a spillover effect related to the lack of appropriate treatment of severe mental illness is imprisonment (President’s Commission, 2002). The costs associated with the lack of treatment due to lack of coverage are likely to be considerable and could be estimated.

SUMMARY

The research reviewed in this chapter points to a number of potential, but not fully documented, relationships between measures of population health within communities and communities’ uninsured rates. It is likely that the poorer health and lesser access to care of uninsured community members affects the health of a

community’s populations overall, through the several mechanisms outlined in this chapter. The uninsured themselves and those who live with and near them are undoubtedly the most directly affected. Because detailed local health status, health outcomes, and insurance coverage data are not available together, or available for enough localities to discern differences among them that could be attributed to the extent of local uninsurance, these findings are qualitative and suggestive rather than definitive.