3

Community Effects on Access to Care

The Committee hypothesizes that the burden of financing care for uninsured persons affects the health services available within the community, especially in urban areas where providers treat large numbers of uninsured persons and in rural areas where providers treat relatively high proportions of uninsured. The strategies taken may be different in rural and urban areas, but the Committee finds plausible the idea that providers in rural and urban settings respond to financial pressures related to uninsurance in similar ways. In an effort to avoid this burden or to minimize its impact on a provider’s bottom line, services may be cut back, relocated, or closed. Staffing may be reduced. This may further strain the capacities of already overcrowded hospital emergency departments, and physicians’ offices or even hospitals may be relocated away from areas of town or entire communities that have concentrations of uninsured persons. Such disruptions may reduce people’s access to care and the quality of care they receive, regardless of their insurance status.

In this chapter, the Committee explores the consequences of community uninsurance for access to care in the context of the present era of rapid change in public and private health care financing. As discussed in Chapter 1, the Committee has chosen to interpret its task as concerning community effects of uninsurance but not of underinsurance, despite the difficulties of disentangling the likely mutual influences of uninsurance and underinsurance and the limits of the existing literature. After a brief discussion of access to care considered in general, the chapter is organized by type of service, examining primary care, emergency medical services and other specialty care, and hospital-based care in turn. The chapter concludes with a discussion of questions for further research and a summary.

Although many of the data and studies are organized by institution or profes-

sion, the Committee takes the perspective of community residents as consumers of health care and reports on local health services arrangements as typically encountered by someone seeking care. Focusing on the types of services as they may be affected by uninsured rates, rather than on providers and institutions, allows a more systematic perspective on the adequacy of health services throughout the community (see IOM, 2001b). In addition, the mere survival of particular institutions may not be a good proxy for the availability of high-quality care (particularly primary care) or for judging the impacts of uninsurance in a rapidly changing health care system or market. Nonetheless, the value of a hospital or clinic may include contributions to a community’s social and economic base or serve as a source of community identity. Thus, changes related to uninsurance may have additional effects beyond those related to access and quality of care. These values are discussed in the next chapter, which addresses some potential social and economic effects of uninsurance.

ACCESS TO CARE

Finding: Persons with low to moderate incomes (less than 250 percent of the federal poverty level), nearly one-third of whom are uninsured, and uninsured persons have worse access to health care services in communities with high uninsured rates than they do in communities with lower rates. The causal influence of the local uninsured rate on measures of access is unclear.

While insurance facilitates access to health care by removing or diminishing financial barriers faced by individuals and families, it also secures a revenue stream for health care providers and institutions (IOM, 2001a, 2002a, 2002b). The Committee hypothesizes that when this revenue stream is diminished by higher local uninsured rates, providers may opt to change their patterns of service provision within the community in an effort to preserve revenues. Depending on the local organization of health services, this provider phenomenon would be expected to affect the opportunities of insured residents to obtain health care. Lower-income residents are particularly likely to be affected by loss of access to care because of their limited economic ability, for example, in rural areas to travel long distances to obtain services unavailable locally or to pay higher costs for care.

Three recent studies examine the relationship between self-reported access to care and community uninsurance in urban areas (Cunningham and Kemper, 1998; Brown et al., 2000; Andersen et al., 2002). All of the studies rely on survey data about self-reported access to care, using a number of different measures (e.g., difficulty obtaining care, not having seen a physician in the previous 12 months).

The first study, based on the nationally representative 1996–1997 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey, examines the differences among metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) larger than 200,000 population in the rates

that uninsured residents reported forgoing, postponing, or having difficulty obtaining needed medical care as a function of the community uninsured rate (Cunningham and Kemper, 1998). The authors show that the rates at which uninsured residents reported difficulties in obtaining care differed more than two-fold over the range of high-uninsured-rate and low-uninsured-rate communities, from about 41 percent (Lansing, Michigan) to 19 percent (Orange County, California), with a national average of 30 percent.1 Only about 15 percent of the variation among the communities in rates of difficulty in accessing care is related to measured differences in the health needs or other population characteristics of the uninsured respondents, indicating that most of this variation is related to unmeasured factors. Concluding that an uninsured person’s place of residence plays a key role in determining ease of access to care, the authors hypothesize that differences in access may reflect the economic make-up of the uninsured person’s community (e.g., providers in wealthier areas may be better able or inclined to deliver free or reduced-price care) or the availability of health care outside of the community (e.g., proximity of multiple health care markets in the larger MSAs) (Cunningham and Kemper, 1998).

Although the first of the three studies discussed focuses only on uninsured residents, it points up how their ability to obtain care depends on their relative numbers within the overall community. Further, the possibility remains that insured residents are affected by local uninsurance in ways not measured in the analysis. The authors report no relationship (correlation) across the 60 communities studied between the proportion of privately insured respondents reporting difficulty obtaining access to care and the proportion of uninsured respondents with access difficulties, as well as different reasons for difficulties, with 90 percent of uninsured respondents citing cost as the key constraint, compared with 48 percent of insured respondents. Yet the often separate experiences of uninsured and privately insured with the organization and delivery of care in urban areas (as described in Chapter 2) may be linked through the effects that uninsurance exerts on the local health care market.

The second study considers the aggregate experiences of all low- to moderate-income residents (earning less than 250 percent of the federal poverty level [FPL]), under age 65 in the 85 largest MSAs in 1997, without distinguishing between insured and uninsured respondents (Brown et al., 2000). The authors examine measures of health care access including forgone or delayed care, no physician visit within the year, and having a regular source of care, as a function of uninsured rate (Brown et al., 2000, data for 1997). Residents of the 12 MSAs with

significantly higher uninsured rates (at least one standard deviation above the mean for all 85 MSAs) reported greater difficulty obtaining health care than did residents of the 17 MSAs with significantly lower uninsured rates, unadjusted for any covariates of unin-surance: 22 percent reported delaying or going without needed health care in MSAs with high uninsured rates, compared to 8 percent in MSAs with substantially lower uninsured rates; the comparable figures for those who reported no physician visit in the past year were 39 and 14 percent in MSAs with high and low uninsured rates, respectively. Since almost one-third of persons under age 65 who earn less than 200 percent of FPL or who are members of families that earn less than 200 percent of FPL are uninsured (Fronstin, 2002), it is likely that a proportion of the effect observed of local uninsured rate reflects the experiences of the uninsured rather than the insured study participants.

The third study complicates conclusions that might be drawn from the findings of Cunningham and Kemper about what unmeasured community-level characteristics may influence the access of uninsured persons to care and the findings of Brown et al. about the relative influence of community uninsurance on insured versus uninsured residents. In a multivariate, cross-sectional study of the likelihood (odds) that low-income children and adults under age 65 have seen a physician in the past year in the 25 largest MSAs nationally, the authors show that a number of individual-level and community-level covariates may better explain differences in access to care than does the community uninsured rate (Andersen et al., 2002). While analytically adjusting for measures of community demand for care (percentage in poverty, uninsured rate, and percentage enrolled in Medicaid) did not change the odds that low-income children and adults would have seen a physician in the past year, taking into account differences in a community’s financial and structural capacity to deliver care (e.g., higher per capita income, lower unemployment, greater income inequality, number of public hospital beds per thousand population, number of community health centers per thousand population, lower degree of managed care penetration) did improve the odds of seeing a physician in the past year (Andersen et al., 2002). Echoing the hypothesis laid out by Cunningham and Kemper, the authors suggest that a possible explanation for their findings is that greater community wealth may strengthen the financial viability of safety-net arrangements, either directly or through the support of higher levels of eligibility for public coverage or higher spending on related public programs.

Together, these three studies provide evidence that, with limited analytic adjustments for the many covariates of insurance status and uninsured rate, an urban area’s uninsured rate is associated with the ability of uninsured and of moderate- and lower-income residents to obtain needed and regular health care. Such measures of access to health services are basic markers of effective, quality care that improves health outcomes (Millman, 1993; IOM, 2002a, 2002b). Longitudinal studies are needed, with adjustments for covariates of insurance status and uninsured rate, to better distinguish whether and how community uninsurance

influences the access experiences of insured and uninsured community members in different ways and to a greater or lesser extent.

PRIMARY CARE

Except for the studies of access to care described in the preceding section, which include measures that can be interpreted as measures of access to primary care, there is little empirical documentation of the relationship between community uninsurance and access to primary care. In this section, the Committee draws on the literature about primary care providers and sites of care, for the most part, physicians and clinics, to develop background information about potential mechanisms and outcomes of community effects.

Uninsurance may compromise access for many community residents to preventive, screening, and primary care services. These services are provided in diverse settings, ranging from general primary care and specialized health department clinics (e.g., immunization, family planning), private physician offices, community health centers, hospital outpatient and emergency departments, and dedicated hospital primary care outpatient clinics (Donaldson et al., 1996). See Box 3.1 for the Committee’s working definition of primary care. Particularly for low-income residents and members of other medically underserved groups, clinics and health centers play a special role in primary health care services delivery due to their close geographical proximity to underserved populations, their cultural competence and history in the community, and their provision of supportive “wrap-around” services that facilitate access to care and quality care (Hawkins and Rosenbaum, 1998). As a result, when uninsurance results in fiscal pressures on community facilities, insured as well as uninsured clients may be affected by reductions in health center services. To make up for the provision of uncompensated care, clinics and health centers may cut back on available services, lengthen waiting times for all patients, and cease operations altogether in some communi

|

BOX 3.1 The Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care defines primary care “as the provision of integrated (that is to say, comprehensive, coordinated, and continuous over time), accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community” (Donaldson et al., 1996). Primary care clinicians typically are physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners, sometimes working together in a team. The ongoing personal relationship between provider and patient that is the ideal in primary care is an integral element of quality health care (IOM, 2001b). |

ties. In Los Angeles County in the latter half of the 1990s, for example, in a survey of private providers who contracted with the county to care for medically indigent patients, respondents reported finding themselves at financial risk, with the potential loss of the provider’s services to the entire community (Grazman and Cousineau, 2000). See Box 3.2 for case studies of uninsurance and primary care in two of the country’s largest urban areas.

Shortages of physicians in rural and urban areas with relatively high uninsured rates can mean less access to primary care for all residents. Access for rural residents is particularly sensitive to reductions in available care, because residents have limited choices to begin with and are likely to face long travel times and distances to reach providers outside their community. Furthermore, rural residents, who tend to be in poorer health and older than residents of suburban and urban areas, are likely to experience greater difficulty traveling these longer distances (Ormond et al., 2000a).

Physicians

Physicians’ decisions about the nature and location of their practice may be influenced by the uninsured rate of the community among other factors (e.g., malpractice insurance costs, the availability of specialty support, the option to practice in large tertiary care hospitals, the safety and overall attractiveness of the community as a place to live). Considerations about where to locate a new practice are likely to differ from those regarding an ongoing practice because established practices may be better able to accommodate charity or other uncompensated care. Many rural areas and lower-income and economically depressed urban neighborhoods have a harder time recruiting and retaining primary care practitioners than do more populous and affluent communities.

For communities in rural areas, uninsurance may make it more difficult for a private physician to maintain a financially viable practice. Physicians in rural areas are more likely to treat Medicaid and uninsured patients and have higher proportions of Medicare patients due to rural demographics (Mueller et al., 1999). As a result, rural physicians may face lower levels of reimbursement. This can place further financial drains on their practices (Coburn, 2002). At the same time, in such areas, safety net arrangements for primary care tend to be informal and not publicly subsidized, especially in the smallest towns (Taylor et al., 2001). A convenience survey of informal safety net arrangements in eight towns across the country (less than 5,000 population) finds that rural hospitals are particularly important in this regard (Taylor et al., 2001). Many rural physicians work in affiliation with or are supported by their community hospital, through either a rural health clinic or the hospital itself. For example, a family practice in Deer Island, Maine, a fishing community in which 60 percent of the residents were uninsured, alleviated its financial problems by affiliating with a local hospital as a rural health clinic (Finger, 1999).

Physicians who serve uninsured patients encounter ethical and legal dilemmas

|

BOX 3.2 Los Angeles County, California Los Angeles County is home to 10 million people, roughly one-quarter of whom (2.5 million persons) are uninsured. Financial pressures on the county health department related to the care of medically indigent and uninsured persons are leading to a reduction in primary care and preventive services and the closing of sites of care for all county residents. The county health department serves an estimated 800,000 patients each year, many of whom are uninsured. Broad cuts in services were averted during a county budget crisis in the mid-1990s through an increase in federal Medicaid payments for outpatient services (totaling more than $2 billion) under a five-year program waiver from the federal government. This waiver was renewed once and is scheduled to expire in 2005. Under the waiver, county health services were reconfigured to emphasize primary care and preventive services, which improved access to care but did not reduce hospital inpatient utilization significantly or result in appreciable cost savings. Recent years’ state Medicaid budget troubles are shared by Los Angeles County. Despite the county’s Board of Supervisors’ efforts to balance the department’s $2.9 billion dollar budget and voter support of a property tax increase earmarked to support hospital trauma centers ($168 million expected annually), a $700 million to $800 million deficit is anticipated in 2003. To reduce this deficit, the county has made cuts in primary care rather than in specialty services, hospital inpatient services, or emergency medical services. According to one news account, decision makers justified this choice by explaining that primary care services are more affordable for the clinics’ clients than specialty services, even though one of the anticipated consequences is increased emergency department (ED) use for non-urgent, primary care. Like hospital EDs elsewhere, those operated by public hospitals in Los Angeles are precluded by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) from limiting the use of their services to persons with health insurance. In June 2002, the county closed 11 of its 18 public health clinics and 1 of its 6 public hospitals. It also scaled back support for 100 private clinics and cut 18 percent of employees (5,000 jobs). This was done as part of efforts to trim the deficit in preparation for negotiations for additional federal or state subsidies. Further downsizing and closings are anticipated to be announced in the coming months.1 New York City New York’s municipal Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC) is the largest public hospital system in the country, overseeing 11 acute care public hospitals and more than 100 local clinics among its varied responsibilities to provide health care to medically underserved groups. HHC serves approximately 1.3 million per- |

|

sons a year, 43 percent of whom are uninsured. About half of all hospital-based care is delivered to uninsured and underinsured residents, and HHC facilities provide a disproportionate share of services more likely to be used by vulnerable populations (e.g., tuberculosis, HIV/AIDs, psychiatric, trauma, alcohol and substance abuse, emergency medical services). Since 1994, HHC has responded to several financial challenges by cutting back funds and shifting patients from hospitals to primary care clinics. During 2001, HHC experienced its first deficit in five years. News accounts attribute part of the $300 million deficit to a 30 percent increase since 1996 in the number of uninsured persons (totaling more than 564,000 uninsured patients in 2000). Other factors include changes in patient mix and volume (e.g., loss of market share to other hospitals), competition for Medicaid patients to fill inpatient beds (given declining inpatient utilization) from private nonprofit hospitals, and a growing gap between uncompensated care and public subsidies (e.g., indigent care dollars from the state, Medicare disproportionate share hospital payments, and appropriated city tax revenue). Uninsured patients account for 10 percent of hospitalized patients and 30 percent of ambulatory care patients in HHC facilities. As Medicaid payments lag behind health care cost inflation, especially for clinic visits, and private sector facilities compete successfully for Medicaid managed care enrollees, Medicaid revenues to HHC facilities have declined. Because patients have been shifted from hospitals to primary care clinics, there has been a 9 percent increase in clinic visits and a 12.5 percent decrease in inpatient admissions since 1992. Because Medicaid managed care payments to primary care clinics are lower than those for hospital care or for specialty services, HHC facilities have been squeezed financially. Despite the known benefits of primary care, HHC has closed and merged preventive and primary health care sites over the past year, including eight neighborhood health centers. After receiving additional funds from the city, HHC decided to keep open 15 school-based clinics slated for closure, although their operations will result in an anticipated $2.7 million loss in 2001. For the most part, the clinics selected for closing are located in immigrant and low-income neighborhoods where roughly two-thirds of the patients are uninsured. Clinics to be closed include 9 of 42 that specialize in children’s health. Overall, the loss of capacity is estimated as 100,000 children served annually. Other cost-control measures include cutting staff and downsizing capacity—for example, decreasing the capacity of the renovated Queens Hospital Center from 300 to 200 beds. These changes have resulted in overcrowding and longer waits at public hospital emergency departments and waiting areas, longer waiting times to get appointments, higher fees for pharmacy services, and lower quality of care. 2 |

that physicians who do not see the uninsured (either by choice or by practice location) can avoid. Anticipating little or no reimbursement for their services, they may have to decide between reducing the amount or nature of the services they provide to patients from whom they do not expect any compensation or seeing fewer uninsured patients in their practices (Weiner, 2001). The decision to limit service for uninsured persons may preserve the financial basis for individual or group practice, but it presents an ethical or moral conflict for many physicians (Weiner, 2001).

Over the 1990s, the proportion of physicians who provided charity care (whether to uninsured or insured persons) declined. The CTS results presented in Chapter 2 show a decline in the proportion of physicians reporting giving charity care from 76.3 to 71.5 percent between 1997 and 2001 (Reed et al., 2001; Cunningham, 2002). The proportion of physicians devoting more than 5 percent of their clinical practice time to charity care also decreased over this period from 33.5 to 29.8 percent, while the proportion devoting less than 5 percent of their practice time to charity care increased from 66.5 to 70.2 percent (Cunningham, 2002). This change is thought to be related to health care market changes, including the shift of physicians from solo and group ownership of practices to becoming employees of larger health services institutions. It may also be related to the financial strain on physician practices and increased time pressures. According to the results of a 2000 CTS survey, even at academic health centers (which serve a safety-net function in many urban areas), 63 percent of affiliated medical school faculty surveyed report that they are discouraged from seeing uninsured patients, by either inadequate payment, their teaching hospital, or their practice group (Weissman et al., 2002).

Physicians who provide charity care also have concerns about malpractice liability that may affect their provision of such care. A random sample survey of California generalist physicians (n = 124) finds that these practitioners’ decisions about accepting new uninsured patients were influenced by the concern that they would be more likely to be sued (49 percent) (Komaromy et al., 1995). This study reported that just 43 percent of those surveyed accepted new uninsured patients compared with 77 percent who accepted new privately insured patients.

Community Health Centers and Clinics

Finding: Serving a high or increasing number of uninsured persons reduces a community health center’s capacity to provide ambulatory care to all of its clients, insured as well as uninsured.

By mission, community health centers (CHCs) are located in areas with limited access to primary care (Davis et al., 1999). For uninsured persons, there is evidence that CHCs provide better access to primary health care, as measured by having a regular source of care and having a physician visit in the previous year, and higher-quality care, as measured by patient satisfaction and meeting Healthy

People 2000 goals for health promotion, prevention, and screening than other ambulatory care providers (Carlson et al., 2001). Expanding the number of CHCs or their capacity to provide services is likely to improve access to primary care for medically underserved groups (Forrest and Whelan, 2000). One survey of primary care access at four types of ambulatory care sites (public facilities, private nonprofits, federally qualified health centers, and other freestanding health centers) in New York City in 1997 found that public sites have the strongest performance for low-income patients in terms of coverage for uninsured persons, services available after business hours, and the availability of wraparound services.2 This study concluded that serving increasing numbers of uninsured persons, in the context of fiscal pressures from Medicaid managed care and fewer Medicaid patients overall, may weaken ambulatory sites’ capacity to provide primary care to all members of the community (Weiss et al., 2001). The loss of ambulatory care clinical services would be particularly damaging to vulnerable populations because these clinics serve higher proportions of low-income and minority group members under age 65 and have safety net missions (e.g., serving farmworkers, homeless persons, or undocumented immigrants) or patients with specific high-risk diagnoses (e.g., tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases, substance abuse).

CHCs face financial pressures on a number of fronts: from reduced income from Medicaid patients, related to the growth of state Medicaid managed care contracting; from reduced public subsidies; and from an increased proportion of their patient mix that is uninsured (Lewin and Altman, 2000). As discussed in Chapter 2, since the 1980s, Medicaid revenues have become more central to supporting clinics and supporting, indirectly, primary care for uninsured persons. During the 1990s, however, the rapid growth of state Medicaid managed care contracting destabilized this revenue stream for CHCs. Between 1980 and 2000, inflation-adjusted federal grant support for CHCs actually dropped 30 percent, even as the number of centers increased 22 percent and the number of uninsured patients served by CHCs grew by 54 percent (Markus et al., 2002). As a result, changes in the Medicaid program both influence uninsured rates and affect the capacity of CHCs to serve all of the members of their target community. For example, when a CHC is not included in a local Medicaid managed care network or when substantial discounts are negotiated as a part of its contract with a managed care network, the CHC’s scope of operations may be compromised (Cunningham, 1996; IOM, 2000a).

The increasing proportion of CHC clients who are uninsured may reflect not only greater numbers of uninsured persons but also the practice, becoming more common, of health care providers’ referring uninsured patients to CHCs rather than accepting such patients for treatment themselves (Hawkins and Rosenbaum, 1998). This phenomenon is akin to “patient dumping,” the transfer of medically indigent patients from private hospitals to public facilities. The result is likely to be the concentration of uninsured patients in safety-net institutions, including CHCs.

Over the long term, the increasing reliance of CHCs on Medicaid revenues, often through managed care contracting, has adversely affected CHCs’ capacity to serve all of their patients, insured as well as uninsured (Shi et al., 2001; Rosenbaum et al., 2002). A survey of CHCs between 1996 and 2000 found that participation in Medicaid managed care contracts was associated with financial losses for CHCs. Still, health centers’ participation in managed care, particularly for Medicaid enrollees, increased more than 50 percent over this four-year period (Rosenbaum et al., 2002). As a result, federal operating grants awarded to CHCs to support care for uninsured persons actually may be compensating the centers for losses incurred from treating insured patients enrolled in Medicaid managed care programs.

The financial difficulties experienced by community health centers may result in narrowing the scope of services offered at these sites and a decrease in the center’s capacity to deliver primary care, including wraparound services that facilitate access to care, for all members of a center’s target population (Hawkins and Rosenbaum, 1998).

Because wraparound services are, for the most part, not reimbursed by Medicaid or other third-party payers, federal grants support these services (McAlearney, 2002). In light of this fact, any increase in the number and proportion of uninsured users at a health center may create financial strains that result in the reduction or elimination of one or more of these enabling services. This is likely to decrease both access to care and quality and continuity of care (USGAO, 2000).

The degree to which CHCs have lost capacity to provide primary care is not uniform nationally. A longitudinal study of 588 CHCs between 1996 and 1999 found that reductions in capacity appear to be concentrated among subsets of health centers with a sizable number or share of uninsured patients or those that have experienced a recent increase in uninsured patients (McAlearney, 2002). Nationally, one-fifth of federally funded CHCs (130 of 700) have a high proportion of uninsured clients (62 percent or higher, rather than the national average of 41 percent). More than half are located in the South, West, or other areas with high uninsured rates (Markus et al., 2002).

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES AND TRAUMA CARE

Finding: Although hospital emergency department (ED) overcrowding is not primarily a consequence of uninsurance within a community, rising uninsured rates can worsen ED overcrowding and the

financial status of ED operations. As a result, community uninsurance is likely to result in lessened availability of hospital emergency services within a community, including reduced availability of on-call specialists.

Finding: A significant source of financial stress on regional trauma centers is the high proportion of uninsured patients that they serve. Hospitals may decline to open a trauma center or may decide to close an existing trauma center in response to this financial stress.

The fates of uninsured and insured community residents meet in the waiting room of their local hospital emergency department. Emergency departments are a key example of how market pressures and public policies (e.g., EMTALA requirements that EDs maintain an “open door” policy, serving all comers without regard to their ability to pay) interact in ways that create incentives for hospitals to reduce their exposure to financial losses associated with serving uninsured patients. The Committee hypothesizes that hospitals’ adaptive strategies with respect to containing financial losses have consequences for all community residents served by the hospital’s emergency department.

Perhaps more so than with hospital emergency departments, the closure of hospital regional trauma centers puts at greater risk the health of everyone in the communities the centers serve. Reliance on the highly specialized and resource-intensive care provided by trauma centers extends throughout populous metropolitan areas and multicounty regions in rural areas, transcending more local neighborhood boundaries that often separate wealthier, insured groups from less wealthy, uninsured ones. The lack of adequate financing for the care of uninsured persons with traumatic injuries thus poses the risk of diminished access to care for all residents of a region. See Box 3.3 for the Committee’s working definition of trauma care.

The following sections discuss the hypothesized community effects on emergency medical services and trauma care for all members of a community with a sizable or growing uninsured population.

Hospital Emergency Departments

Hospital emergency medical services often do not, and frequently are not, expected to make a positive contribution to a hospital’s overall financial margins, particularly as hospital accounting practices do not credit patient revenues from persons admitted through the emergency department, as some 40 to 60 percent of all admissions are (Bonnie et al., 1999). Typically, hospital emergency departments and trauma centers provide what are considered community benefits, often unremunerative services offered in exchange for a hospital’s nonprofit status and tax exemption (Kane and Wubbenhorst, 2000; Nicholson et al., 2000) (see discussion of community benefits in Chapter 2). Hospitals’ ability to cross-subsidize community benefits have been limited by an increasingly competitive market for hospital services during the 1990s. In addition, as managed care plans have negotiated

|

BOX 3.3

|

contracts for hospital services, some have excluded high-cost providers (including those that offer advanced trauma care) from networks or restricted enrollee’s use of them to cases in which the technologically advanced care was clearly needed, thereby undercutting hospitals’ ability to spread the costs of expensive service capacity across many (lower-severity) patients (Malone and Dohan, 2000).

In many urban and rural areas, hospital emergency departments are often filled beyond capacity. A recent survey of 1,501 hospitals (approximately 36 percent of all hospitals nationally with EDs) finds that 62 percent report their EDs to be at or over capacity (Lewin Group, 2002). A survey of California ED directors in a range of settings (university, county, and private hospitals) finds that virtually all respondents cited overcrowding as a problem (Richards et al., 2000). Ninety-one percent of ED directors responding to a recent national survey report overcrowding problems in their departments, with 39 percent reporting overcrowding on a daily basis and little difference between overcrowding in academic health centers and in private hospitals (Derlet et al., 2001).

A key cause of ED overcrowding appears to be an insufficient number of active or staffed inpatient beds into which ED patients can be admitted.3 This bed

shortage is in part a result of market and related financing pressures on hospital operating margins, pressures that include the relative amount of uncompensated care provided by the hospital, some of which is delivered to uninsured patients. When an ED cannot move seriously ill or injured patients into inpatient beds in a timely fashion, a logjam or backup of patients boarded in the ED can be created. If this backup becomes severe, the ED may temporarily close its doors to new patients who arrive by ambulance, diverting them to other area hospitals (Brewster et al., 2001). When a hospital is on diversion status, ED services are unavailable, although ambulatory (walk-in) patients may continue to arrive and wait to be seen.

The pressures on EDs created by a shortage of available inpatient capacity have been intensified by an increasing demand for ambulatory care services at hospital emergency departments, by both insured and uninsured patients, as a consequence of inadequate access to primary care in the community (Derlet, 1992; Grumbach et al., 1993; Baker et al., 1994; Billings et al., 2000). In addition, EMTALA has unintentionally fostered the use of scarce ED resources for non-urgent care (Fields et al., 2001).4 The costs of care provided through EDs often are not reimbursed in full (e.g., claims for urgent care may be challenged or rejected by managed care plans, and uninsured patients are estimated to pay only a percentage of their bills for ED care) (Johnson and Derlet, 1996; Kamoie, 2000).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the rising number of uninsured persons was clearly identified as contributing to the overcrowding of hospital emergency departments (Melnick et al., 1989; USGAO, 1993; McManus, 2001). Their growing numbers resulted in diminished access to emergency medical services, at least at large urban teaching hospitals. Overcrowding in the past few years, however, reflects a more complex set of interactions and is likely to reflect the effects of a community’s rising number or concentration of uninsured persons only in specific instances, for example, in the case of a large urban public hospital without adequate funding to support care for the greater number of uninsured patients. Overall, the number or proportion of uninsured patients in a community is likely to contribute to ED overcrowding only indirectly (USGAO, 2000; Derlet, 2002). See Box 3.4 for a case study of uninsurance and EDs in Arizona.

Overcrowding adversely affects the quality of care for all emergency department patients through longer waits to be seen and admitted and longer transport times to the hospital if some area emergency departments have been temporarily closed (Bindman et al., 1991; Kellermann, 1991; Rask et al., 1994). The problems ED patients then face range from dissatisfaction to needless suffering and adverse health outcomes. A survey of 30 emergency departments in Los Angeles County in 1990 found that about one of every twenty patients left before receiving treatment (Stock et al., 1994). In overcrowded EDs, staff experience greater

|

4 |

See Chapter 2 for a brief discussion of EMTALA. |

|

BOX 3.4 Like all hospitals, those in Arizona are subject to EMTALA, and like many other hospitals around the country, Arizona facilities have had to cope with a relatively high uninsured rate locally, a high degree of managed care penetration in local health services markets, and a rising patient volume at hospital emergency departments. In addition, Arizona hospitals also face the highest burden nationally of uncompensated emergency care, reflecting a rapid growth in the size of the local low-income population and the fact that a sizable proportion consists of undocumented immigrants, meaning that they are ineligible for Medicaid (MGT of America, 2002). Although hospitals do not formally document the immigration status or ethnicity of their patients, one recent study indicates that 16 Arizona hospitals along the Mexican border provided $44 million in expenditures over a three-month period in 2001 to treat uninsured, medically indigent immigrants. Overall, in 2001, Arizona’s 10 hospitals reported providing $525 million in uncompensated care. Hospital officials attribute the growth in uncompensated care expenses to a number of developments: the sheer number of low-income undocumented immigrants living and working in the state, the lack of reimbursement from the federal Immigration and Naturalization Service for health care services delivered to persons apprehended but not officially in custody, difficulty discharging patients out of the country for follow-up care, and the humanitarian practice of parole, or allowing Mexican residents in need of emergency medical services to obtain them at facilities on the U.S. side of the border, given the lack of trauma centers in nearby Mexico. After a November 2001 clarification of federal Medicaid regulations resulted in the disqualification of undocumented immigrants from receiving kidney dialysis and other treatments previously considered emergency services, the state legislature allocated $2.8 million in temporary Medicaid funding, from tobacco settlement dollars, to pay for dialysis and related care needed by approximately 150 uninsured, medically indigent immigrants. The state’s funding meets both humanitarian and fiscal needs, since access to care is anticipated to reduce patients’ utilization of the costly hospital emergency services expected to be needed if they could no longer afford regular dialysis. SOURCES: Associated Press, 2001, 2002; Duarte, 2001; Taylor, 2001; Arizona Daily Star, 2002; Erikson, 2002; Gribbin, 2002; MGT of America, 2002. |

frustrations and lower productivity, which may create an unsafe workplace (Derlet and Richards, 2000; Brewster et al., 2001). Emergency departments are expected to treat emergency conditions only and are not rewarded by their parent institutions for providing comprehensive care. Emergency department physicians and other personnel are thus caught between professional ethical standards and ideals of excellence and institutional pressures to minimize uncompensated care expenses. A financially unstable ED may even put its affiliated hospital in danger of closing (Malone and Dohan, 2000).

Although both insured and uninsured members of the community are likely to be adversely affected by overcrowded emergency departments, members of medically underserved groups are particularly likely to suffer because they have fewer options to obtain primary care outside EDs, compared with insured persons (Felt-Lisk et al., 2001; Weinick et al., 2002). The promise of EMTALA, that an uninsured person will at least be seen and medically stabilized, and the generally high quality of acute care and its around-the-clock accessibility, make the hospital emergency department a logical choice for uninsured patients (Kellermann, 1994; Young et al., 1996). For some, it may be their only option for receiving medical attention. However, despite the greater likelihood that uninsured persons will use EDs relative to other ambulatory care settings, they still use EDs less frequently than do Medicaid and privately insured patients (Cunningham and Tu, 1997; Billings et al., 2000; IOM, 2002a).

Financial stresses on hospitals related to EDs also contribute to the difficulty that many hospitals are experiencing in recruiting medical specialists to serve on on-call panels that EMTALA requires hospitals to maintain (Asplin and Kropp, 2001).5 Specialists may decline to serve on these panels because of the high numbers of uninsured patients they would be obligated to treat without any assurance of compensation (Johnson et al., 2001). When a hospital cannot summon an appropriate on-call specialist, the emergency department is forced to transfer the patient needing specialty care to another facility, adding to the cost of care, delaying needed care, and potentially leading to needless suffering, disability, or even death.

For example, in Phoenix, Arizona, which has a 17 percent uninsured rate (2001), some specialty physicians (e.g., orthopedists, neurosurgeons) have ended their hospital affiliation or refused to participate in on-call panels of area hospital EDs, in order to avoid treating uninsured patients for whom they do not expect to be reimbursed (Draper et al., 2001b). This has resulted in a shortage of specialty services both in emergency departments and within the community generally, as some specialists have organized their own group practices and hospitals on a for-profit basis or have collectively negotiated for higher payments from hospitals (Taylor, 2001). Likewise in California, nonprofit hospitals and academic health centers have experienced a shortage of specialists willing to serve in an on-call capacity to emergency departments (Johnson et al., 2001). A number of factors influence the reluctance of physicians to serve on on-call panels (e.g., coverage and payment limitations from both public and private insurance plans, high malpractice insurance rates). High levels of uninsured patients, together with the legal mandate of EMTALA, may represent the last straw and lead specialist physicians to drop participation in on-call panels.

Preserving the adequacy of the capacity for emergency and trauma care is a community-wide concern. Ideally, services should be coordinated regionally as well as within health services markets (Bonnie et al., 1999). When an individual hospital responds to ED overcrowding by diverting ambulances to other hospitals, it can trigger a wave of ED closures and ambulance diversions. When this occurs, the access to emergency medical care for all community residents is adversely affected. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century has identified the limited capacity of the nation’s hospitals to accommodate “surges” or sudden influxes of severely ill or injured patients as a system weakness that remains to be addressed by public health policy (IOM, forthcoming 2003).

Trauma Centers

Trauma centers often are “loss leaders” within hospitals, with the explanation for this attributed to rising health care costs, inadequate reimbursement for services provided, and unfavorable changes in health services financing (Dailey et al., 1992; Bonnie et al., 1999; Selzer et al., 2001). The successful organization of regional trauma systems, specifically the use of prehospital triage, has resulted in the most severely injured patients being admitted to trauma centers (Eastman et al., 1991; Rhee et al., 1997). The greater proportion of sicker patients at Level 1 trauma centers (who require more expensive care for which payment may not be automatic or complete), the greater proportion of uninsured patients, and the greater likelihood of seeing low-income patients, given their urban location, affiliation with safety net institutions, and type of injury, have each been identified as factors contributing to financial losses (Saywell et al., 1989a; Bazzoli et al., 1996; Fleming et al., 1992; Selzer et al., 2001). Trauma centers that have positive revenue margins tend not to be located in urban areas or tend to see patients who have health insurance (Taheri et al, 1999).

Trauma patients are more likely to be uninsured, compared with all hospital patients. One national but nonrepresentative survey of 25 Level 1 or 2 trauma centers in the late 1980s reported that 31 percent of trauma patients were uninsured, compared with 9 percent of hospital patients overall (Eastman et al., 1991). This large share of uninsured patients in trauma centers resulted in an overall negative financial margin (revenues less than costs) of nearly 20 percent. In addition, the expenses of uninsured patients related to trauma care are, almost by definition, less likely to be reimbursed. In a four-year study of one community hospital’s trauma registry, 211 patients with penetrating injuries related to assault (e.g., firearms, knives) generated more than $2 million in hospital charges (Clancy et al., 1994). Two-thirds of these charges were incurred by uninsured patients; only 30 percent of the $2 million was reimbursed.

Furthermore, along with the rest of the hospital industry, the financial margins for regional trauma center systems have been narrowed since the early 1990s, particularly in urban areas, with the transition in public program financing from

fee-for-service to prospective payment and managed care and with commercial managed care for private payers. According to one recent literature review, during the 1990s, trauma centers were able to bring in revenue to cover 71 percent of their estimated costs, when a cost-to-charge ratio was used as the base for calculations (Fath et al., 1999). In an analysis of regional trauma system development in 12 urban areas during the 1990s, Bazzoli and colleagues (1996) credited Medicare and Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, along with state and local subsidies to trauma centers, with sustaining trauma services within communities.

The high proportion of uninsured patients found in a trauma center can threaten its financial viability. A study of trauma care costs in a large urban teaching hospital in Detroit, Michigan, looked at all trauma patients over a one-year period (1996–1997), calculating actual costs for 667 insured patients ($10.3 million) and estimating costs for 96 uninsured patients ($1.6 million), for whom financial data were missing (Fath et al., 1999). Insured and uninsured patients had similar demographic characteristics and injury severity. For patients who stayed a relatively short time (seven days or fewer), hospital revenues exceeded costs by 17 percent, but for trauma patients as a group, revenues were only 87 percent of costs. Overall, the trauma center lost money. Citing other case studies as well as their own work, Fath and colleagues suggest that the urban location of many trauma centers means that their patient base will be more likely to be uninsured and at higher risk for trauma. A study of an urban Level 1 trauma center in Indiana over a six-month period included all 553 trauma patients for whom billing records were available (Selzer et al., 2001). Over six months, charges for these cases exceeded direct reimbursements by $2.1 million. Self-pay or charity patients, presumed to be uninsured, comprised 41 percent of the trauma patients in the study (224 persons), including 32 percent of the blunt injury patients, 37 percent of the penetrating injury patients, and 38 percent of the burn patients.

SPECIALTY CARE

Finding: Relatively high uninsured rates are associated with the lessened availability of on-call specialty services to hospital emergency departments, and the decreased ability of primary care providers to obtain specialty referrals for patients who are members of medically underserved groups.

Evidence about the relationship between uninsured rate and access to specialty services other than emergency medical care is limited. In the section that follows on hospital-based care, the Committee presents the results of its commissioned analyses, which include quantitative findings about the influence of community uninsurance on specialty services. As background to that discussion, this section describes likely mechanisms or pathways through which specialty care may

be affected, drawing on examples from the literature on specialist provider location and on specialty care provided by academic health centers.

Emergency medical services constitute one type of specialty care that is likely to be less available to all community members as a result of a community’s relatively high uninsured rate. As discussed earlier in this chapter, physicians (including generalists as well as specialists) are devoting fewer hours to charity care, which as measured does not distinguish between insured and uninsured recipients of this free and reduced-price care. This means that there are fewer referrals available for both uninsured patients and lower-income insured patients who share the same set of medical facilities and practitioners. This effect is more likely to occur in rural communities and central city neighborhoods, where the local economy may not sustain private physician practices. Another consequence of on-call obligations that hospitals may require of affiliated specialists may be the relocation of orthopedists, neurosurgeons, and other specialists out of the area, leading to local shortages of particular specialty services. EMTALA places the burden of maintaining on-call panels on hospitals, rather than physicians, feeding a dynamic where hospitals pressure specialists to participate as a condition of the provider’s continued affiliation (Bitterman, 2002). This dynamic accelerates the movement of specialists to relocate or, more often, drop their medical staff privileges in favor of opening an ambulatory surgical center or a boutique specialty hospital that does not include an emergency department.

Insured and uninsured rural residents alike may experience lessened access to specialty care (as with primary care) if providers leave the community because of financially unviable practice conditions (Ormond et al., 2000a). Rural areas tend to have shortages of specialty physicians, and referrals are often to specialists in urban areas, which may deter some patients from obtaining care or result in their seeking it later than advisable. Specialists who see patients at rural hospitals are key in preventing the loss of privately insured patients to larger urban hospitals, maintaining a broader payer mix to counterbalance the financial effect of patients for whom reimbursement is lower or absent (e.g., publicly insured and uninsured patients) at the rural hospital (Ormond et al., 2000b).

The inability of primary care providers to make specialty referrals for their patients may be an effect of relatively high local uninsurance. For example, while community health centers may have relationships with hospitals in the community that enable them to make specialty referrals for uninsured patients more easily than physicians in private practice, referrals may not come easily. In a study of access to care at 20 CHCs in 10 states, respondent providers reported that they had difficulty obtaining specialty referrals for all their patients, not only those who were uninsured (Fairbrother et al., 2002). Another descriptive study of rural counties in five states also reports that community health centers have difficulty obtaining specialty referrals for their patients, many of whom are uninsured (Ormond et al., 2000b).

Urban safety-net hospitals and academic health centers (AHCs), major sites

for specialty care in their communities, are also affected by high levels of uninsured patients (Gaskin, 1999). A study of 125 public and private AHCs between 1991 and 1996 concludes that a small increase in the proportion of uncompensated care provided by AHCs (as a proportion of gross patient revenues) reflects the combination of a decrease in bad debt and a 40 percent increase in the amount of charity care provided (Commonwealth Fund, 2001). Over that period, in local markets with high managed care penetration, care for uninsured persons had been increasingly concentrated at a subset of AHCs, resulting in less revenue overall. For private AHCs, particularly those that are not located in neighborhoods with high uninsured rates (e.g., central city), one strategic response of hospitals to such cost pressures has been to eliminate specialty services with relatively poor rates of reimbursement, such as burn units, trauma care, pediatric and neonatal intensive care, emergency psychiatric inpatient services, and HIV/AIDS (Gaskin, 1999; Commonwealth Fund, 2001). Public academic health centers or safety net hospitals in central city neighborhoods often are the only source of specialty care for local residents and may find it difficult to reduce or eliminate such services. A study of urban safety-net hospitals during the 1990s finds a decline in the provision of specialty services. However, because the hospitals’ initial array of specialty services was greater than at other hospitals, the volume and proportion of some of these services in safety net hospitals remained relatively high (Zuckerman et al., 2001a). In addition, to the extent that AHCs trim or eliminate certain specialty services, their teaching mission may be adversely affected.

HOSPITAL-BASED CARE

Finding: Community uninsurance can put financial stress on hospital outpatient and inpatient departments, sometimes resulting in lessened availability of services or the closing of a hospital. When public jurisdictions respond to this and other financial pressures by converting their hospitals to private ownership status, the availability of services may be adversely affected, especially for members of medically underserved groups.

In addition to the impacts of uninsured clients on EDs and hospital-based specialist services, hospital inpatient care is also affected by the level of uninsurance within the community. Hospitals treating uninsured patients must contend with the cumulative effects of inadequate care for chronic conditions, exacerbated acute illnesses, and delayed treatment among uninsured patients (IOM, 2002a). The more intensive and costly care that uninsured patients may eventually require because of having forgone care earlier in the course of their illness is frequently provided by hospitals. In addition, hospital outpatient departments and their satellite clinics are an important source of both primary and specialty care for medically underserved populations, including uninsured persons and their families.

Hospital Services

One way that hospitals have responded to increasing financial pressures is to stem the use of certain services known to attract persons who are more likely than average to be uninsured. The reduced availability or complete loss of these services (e.g., trauma, burn care, care for HIV/AIDs) may be expected to affect everyone in the health services market who needs them. As described in a previous section on emergency medical services, one dynamic seen recently within hospitals is a relative shortage of staffed inpatient beds, compared with the overall demand for admissions. When ED patients requiring admission end up waiting in the emergency department for a staffed inpatient bed that is open, ED capacity is limited and subsequently access to care for all members of the community is diminished. Favoring elective admissions over those from the ED reduces the hospital’s inpatient uncompensated care “exposure” because patients admitted from the ED tend to involve more costly care and are less likely to be well insured, if insured at all.

A survey of urban, nonfederal, acute care hospitals (n = 2,668) between 1990 and 1997 finds that the 498 safety-net hospitals (defined as hospitals with a high proportion of uncompensated care expenses relative to other hospitals in their market, a high percentage of total expenses that are uncompensated, or both) reported slower growth in the numbers of patients admitted and fewer births, on average, compared with non-safety-net hospitals (Zuckerman et al., 2001a). This trend reflects the impact of Medicaid managed care competition for patients, as well as the adverse financial effects of serving a sizable uninsured population.

New Analysis of Hospital Services and Financial Margins

Finding: Higher uninsured rates in urban areas are associated with lesser total inpatient capacity and fewer population-adjusted medical-surgical, psychiatric, and alcohol and chemical dependence beds. In rural areas, higher uninsured rates are associated with a lower number of population-adjusted intensive care unit (ICU) beds, especially where uninsured patients are not concentrated at specific hospitals within the area.

Finding: Higher uninsured rates in urban areas are associated with a smaller proportion of hospitals offering services for vulnerable populations, including psychiatric inpatient, psychiatric emergency, psychiatric outpatient, alcohol and chemical dependence, and AIDS services. In rural areas where uninsured patients are not concentrated at specific hospitals, higher uninsured rates are associated with a decreasing proportion of hospitals offering psychiatric inpatient services.

Finding: Higher uninsured rates in urban areas are associated with smaller proportions of hospitals offering trauma care, burn care, and tomography (SPECT). In rural areas where uninsured patients are not concentrated at specific hospitals, higher uninsured rates are associated with smaller proportions of hospitals offering transplants, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), radiation therapy, and lithotripsy (ESWL).

Finding: Higher uninsured rates in urban areas are associated with smaller proportions of hospitals offering such community services as community outreach and Meals on Wheels. In rural areas where uninsured patients are not concentrated at specific hospitals, higher uninsured rates are associated with smaller proportions of hospitals providing Meals on Wheels.

Finding: For urban areas, higher uninsured rates are associated with lower inpatient capacity and fewer services but not lower financial margins. In comparison, hospitals in rural areas with relatively high uninsured rates are more likely to maintain inpatient capacity and services provision but to have lower financial margins.

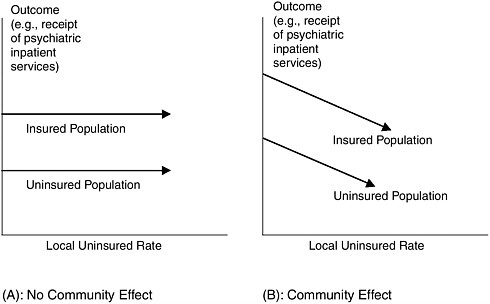

The Committee commissioned two analyses of hospital services and financial margins as a function of local uninsured rates, which are included in Appendix D. Because of the limited data available and identified limitations in the modeling and analytical adjustments, these analyses are exploratory rather than definitive. They are first steps toward testing the hypothesis that uninsurance adversely affects access to hospital-based care for community residents. Figure 3.1 depicts the hypothesized relationship between the independent variable (community uninsured rate) and one of several dependent variables (level of psychiatric inpatient services) tested in the analyses, with analytic adjustments for measured covariates of a community’s uninsured rate.

Both analyses use data from four years (1991, 1994, 1996, 1999) considered cross-sectionally as multiple data points rather than longitudinally, to assess relationships between uninsured rates, hospital services and financial margins. The first of the two analyses looks at the experiences of nonfederal, short-term (acute care) hospitals in the largest 85 MSAs (Gaskin and Needleman, 2002).6 The second analysis looks at hospitals in rural (defined as all nonmetropolitan) counties in an opportunity sample of seven states (California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New

FIGURE 3.1 Community effects diagram.

York, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin), using hospital discharge data to approximate uninsured rates at the county level (Needleman and Gaskin, 2002). Five types of dependent variables were chosen, to better understand the potential relationship between community uninsured rate and access to care not only for medically underserved, low-income or vulnerable populations but also for all community residents. These included measures of inpatient capacity, services generally offered by hospitals and those typically offered by safety net hospitals, and financial margin (Reuter and Gaskin, 1997; Gaskin, 1999).

The economic or policy significance of statistically significant associations seen between the community uninsured rate and access to services depends on the average number of beds and services for the hospitals in the areas studied. For example, a 5 percentage-point decrease in the availability of a high technology service associated with a 1 percentage-point higher uninsured rate may be expected to have more of an adverse effect on rural communities, where the level of services provision is lower than in urban areas. For a rural area, such a decrease may mean the loss of the service entirely and the need for local residents to travel to a neighboring urban area to obtain the service. Table 3.1 presents the means and standard deviations for the independent and dependent variables used in the two analyses. Except for two measures of inpatient capacity (total number of beds and number of medical-surgical beds), the bed, services, and margin variables all have higher means in the urban areas studied than in the rural areas. The confidence intervals for most of the dependent variables in the rural analysis are broader than for the urban analysis, with many including zero; the broad variation in

measures of beds, services, and margins reflects the heterogeneity of rural health services markets.

Area-Level Analyses

Table 3.2 displays the statistically significant findings from the urban and rural area analyses. Interpretation of these results is limited by their imprecision due to insufficient variation in the sample and model; see Appendix D for more discussion.

Urban Areas

For the 85 urban areas examined (the MSA analysis), higher uninsured rates are associated with fewer beds per capita, lower levels of services, and a lower financial margin. Analytically adjusting (weighting) the analysis to take into account hospital size changes some of these findings, yielding an association of higher uninsured rates with greater availability of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and angioplasty and erasing the association with financial margin. These findings are discussed in more detail below.

The urban area analysis of services and margins includes weighting for hospital size, as measured by a hospital’s share of beds as a proportion of hospital beds in the MSA. In the case of the service variables, for example, the unweighted model gives equal emphasis to smaller and larger MSAs and to smaller and larger hospitals. The weighted model examines the proportion of beds in hospitals that offer the service, attaching greater weight to larger hospitals. This is based on the rationale that changes in the level of services offered by a larger hospital are more likely to affect a community more broadly, compared with the offerings of a smaller hospital.

Reading across Table 3.2, for measures of inpatient capacity, an uninsured rate 1 standard deviation (5.3 percentage points) above the mean uninsured rate (14.6 percent) for the 340 MSA observations is associated with a 4.5 percentage-point decrease in the total number of beds per 100,000 population, a 6.1 percentage-point decrease in medical–surgical beds, a 17.5 percentage-point decrease in psychiatric beds, and a 25.8 percentage-point decrease in alcohol and chemical dependency beds. Interpreting these changes in terms of the number of beds in the “average” urban area, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with a decrease in total beds per 100,000 population from 316.2 beds (the mean number) to 302 beds and the loss of 1 of almost 4 alcohol and chemical dependency beds.

For services disproportionately used by vulnerable populations, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with a 14.7 percentage-point lower proportion of hospitals in the MSA that offer psychiatric inpatient services, a 23.2 percentage-point lower proportion offering alcohol and chemical dependence services, and a 4.6 percentage-point lower proportion offering AIDS services. In

TABLE 3.1 Means and Standard Deviations for Independent and Dependent Variables

|

Rural (County)2 |

|||||

|

Unweighted |

Weighted |

||||

|

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

N |

Mean |

S.D. |

|

426 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

|

||

|

422 |

423.3 |

392.3 |

|||

|

396 |

186.8 |

146.5 |

|||

|

396 |

17.8 |

22.1 |

|||

|

396 |

10.0 |

19.1 |

|||

|

396 |

4.2 |

16.0 |

|||

|

396 |

21.7 |

37.2 |

396 |

23.7 |

39.0 |

|

396 |

35.1 |

43.7 |

396 |

37.4 |

44.9 |

|

396 |

15.7 |

33.5 |

396 |

16.5 |

34.5 |

|

396 |

17.3 |

33.1 |

396 |

17.7 |

34.1 |

|

400 |

39.6 |

44.1 |

396 |

42.4 |

45.9 |

|

396 |

16.1 |

33.4 |

396 |

16.6 |

34.1 |

|

426 |

2.7 |

12.9 |

422 |

3.7 |

16.7 |

|

400 |

6.0 |

21.8 |

396 |

6.4 |

22.8 |

|

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

396 |

20.1 |

36.0 |

396 |

21.3 |

37.4 |

|

400 |

13.4 |

29.9 |

396 |

15.5 |

32.6 |

|

396 |

3.6 |

16.0 |

396 |

4.5 |

18.5 |

|

396 |

20.6 |

36.6 |

396 |

21.6 |

37.8 |

|

396 |

6.6 |

21.9 |

396 |

7.4 |

23.8 |

|

258 |

51.8 |

44.4 |

258 |

52.5 |

45.1 |

|

258 |

9.9 |

25.0 |

258 |

10.5 |

27.1 |

|

258 |

18.9 |

35.2 |

258 |

18.5 |

35.8 |

|

414 |

1.8 |

5.9 |

|

||

TABLE 3.2 Selected Regression Coefficients of Hospital Services and Financial Margins on Percent Uninsured, Area Analysesa

|

|

Urban (MSA)1 |

|||

|

Unweighted |

Weightedc |

|||

|

Dependent Variables |

Coeff. |

Change associated with uninsured rate 1 S.D. above the meanb (%) |

Coeff. |

Change associated with uninsured rate 1 S.D. above the meanb (%) |

|

Inpatient Capacity (beds per 100,000 population) |

|

|||

|

Total |

–2.67 |

–4.5 |

||

|

Medical–surgical |

–2.00 |

–6.1 |

||

|

ICU Psychiatric |

–0.61 |

–17.5 |

||

|

Alcohol and chemical dependence |

–0.19 |

–25.8 |

||

|

Services for Vulnerable Populations |

||||

|

Psychiatric inpatient |

–1.10 |

–14.7 |

–1.10 |

–9.8 |

|

Psychiatric emergency |

–1.40 |

–18.3 |

–1.30 |

–11.8 |

|

Psychiatric outpatient |

–1.27 |

–20.7 |

–1.36 |

–14.6 |

|

Alcohol and chemical dependence |

–1.13 |

–23.2 |

–1.31 |

–18.4 |

|

AIDS |

–0.47 |

–4.6 |

|

|

|

High-Technology Services |

||||

|

Trauma |

–0.62 |

–14.7 |

–0.63 |

–8.7 |

|

NICU |

|

0.61 |

7.5 |

|

|

Transplant Burn |

–0.17 |

–17.2 |

|

|

|

MRI Radiation therapy Angioplasty |

|

0.46 |

4.0 |

|

|

SPECT ESWL |

–0.65 |

–8.4 |

|

|

|

Community Services |

||||

|

Community outreach |

–1.15 |

–10.7 |

–0.77 |

−5.4 |

|

Transportation Meals on Wheels |

–0.52 |

–22.4 |

|

|

|

Margin |

–0.14 |

–21.8 |

|

|

|

aResults (coefficients) are reported if they are statistically significant at p<0.05. bPercent change is calculated as the value of the coefficient, multiplied by the value of 1 standard deviation from the mean of the independent variable (percent uninsured for the urban analysis, percent uninsured discharges for the rural analysis), divided by the mean value of the dependent variable. cFor the urban analysis, inpatient capacity and services are weighted by a hospital’s share of beds as |

||||

|

Rural (County)2 |

|||

|

Weighted and unadjusted for concentration |

Weighted and adjusted/not concentratedd |

||

|

Coeff. |

Change associated with % uninsured discharges 1 S.D. above the meanb (%) |

Coeff |

Change associated with with % uninsured discharges 1 S.D. above the meanb (%) |

|

–0.45 |

–11.1 |

–0.54 |

–13.3 |

|

|

–0.64 |

–15.8 |

|

|

|

–1.38 |

–25.6 |

|

|

|

–0.96 |

–66.0 |

|

|

Not studied |

Not studied |

||

|

–1.67 |

–34.5 |

–1.99 |

–41.1 |

|

|

–1.41 |

–40.0 |

|

|

−0.91 |

–54.1 |

–1.04 |

–61.8 |

|

|

|

–1.27 |

–30.2 |

|

−0.17 |

−37.4 |

–0.22 |

−48.4 |

|

a proportion of hospital beds in the MSA (a measure of availability). For the rural analysis, inpatient capacity is weighted by average county population and services by the percentage of hospitals offering the services. dAdjusting for the relative concentration of uninsured patient discharges, or the relative degree of clustering of uninsured patients at hospitals within the area, as measured by the ratio of the Herfindahl index for uninsured discharges over the Herfindahl index for all discharges. SOURCES: 1Gaskin and Needleman, 2002; 2Needleman and Gaskin, 2002. |

|||

the case of psychiatric inpatient services, this association translates into a decline in the proportion of hospitals offering this service from 39.6 percent (the mean across all MSA observations) to 33.8 percent. Adjusting the analysis by hospital size, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with between a 9.8 percentage-point and 14.6 percentage-point lower proportion of psychiatric beds in hospitals offering these services and an 18.4 percentage-point lower proportion of alcohol and chemical dependence beds in hospitals that offer that service. Compared with an urban area with the “average” uninsured rate, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with a decline from 37.8 percent to 30.9 percent of alcohol and chemical dependence beds in hospitals offering this service.

For high-technology services, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with a 14.7 percentage-point lower proportion of hospitals offering trauma services, a 17.2 percentage-point lower proportion offering burn services, and an 8.4 percentage-point lower proportion offering tomography (SPECT). These changes translate into a decline from 22.3 to 19.0 percent of hospitals offering trauma services, from 5.2 to 4.3 percent of hospitals offering burn services, and from 41.2 to 37.7 percent of hospitals offering SPECT. Adjusting the analysis for hospital size, a 5.3 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with an 8.7 percentage-point lower proportion of trauma beds in hospitals offering the service, a 7.5 percentage-point higher proportion of neonatal intensive care, or NICU, beds and a 4 percentage-point higher proportion of angioplasty beds in hospitals offering these services. The case of greater NICU availability may reflect the greater relative need for neonatal intensive care in communities with higher uninsured rates, the fact that this need is usually accompanied by eligibility for public coverage, and the more extensive coverage of pregnant women and newborns by public insurance programs, compared with public coverage of the population overall (Howell, 2001; IOM, 2002b). The finding of greater availability of angioplasty services in higher uninsured rate urban areas may reflect regional differences in practice patterns (e.g., the procedure is more common in the South and West, which also have higher uninsured rates) that are unmeasured and unadjusted for in the analyses (Pilote et al., 1995; Krumholz et al., forthcoming 2003).

Rural Areas

The associations between uninsurance in rural counties (measured as the percent of all hospital discharges in the county that are uninsured) and measures of beds, services, and financial margins follow a pattern similar to that seen in the urban area analysis. In addition, the rural analysis includes an adjustment for the degree to which uninsured patients were clustered at particular hospitals within a given county. The concentration of patients may reflect competitive strategic interactions among hospitals. For example, a hospital may eliminate a service it cannot support with its patient and payer mix. This could allow a competing

hospital to add to its caseload while lowering per-patient costs and making a profit on the service. Table 3.2 includes two sets of coefficients for the rural area analysis, one in which a general effect is found related to the uninsured rate and a second set in which a significant association is observed only when uninsured patients are not clustered at particular hospitals within the county; see Appendix D for details.

For the rural counties studied, higher uninsured rates are associated with lower inpatient capacity for ICU services and, where uninsured patients are not concentrated at specific hospitals, psychiatric inpatient services. A 4.4 percentage-point higher uninsured rate (one standard deviation above the mean percent uninsured discharges of 4.4 percent for the 426 nonmetropolitan county observations) is associated with a 11.1 percentage-point decrease in the number of ICU beds per 100,000 population. When patients are not concentrated at hospitals (adjusted model), the size of the effect increases. A 4.4 percentage-point higher uninsured rate is associated with a 13.3 percentage-point decrease in the number of ICU beds per 100,000 population and a 15.8 percentage-point decrease in the number of psychiatric beds. Viewing the adjusted percentage changes in terms of the number of beds in the “average” rural county, the findings indicate a decrease from 423.3 ICU beds (the mean number) to 367 ICU beds and a decrease from 10 to 8.4 psychiatric beds per 100,000 population.