State and Local Immunization Issues in California

State and local health departments are both essential components of the immunization system. Responsibility for broad program oversight and management generally rests at the state level. Local health departments play a critical role in implementing immunization programs through activities that can include operating immunization clinics, conducting community outreach, and with the advent of Vaccines for Children (VFC), working with participating private providers who deliver most immunization services.

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH SERVICES

Natalie Smith, chief of the Immunization Branch of the California Department of Health Services, reviewed the state’s leading immunization activities and concerns related to the components of the immunization system outlined in Calling the Shots. She observed that serving a population of 35 million people poses substantial operational and financial challenges for the state. In terms of vaccine purchase, about 60 percent of the state’s vaccine doses are purchased with public funds (federal, state, or local), but about 80 percent of vaccinations are delivered by private providers. Dr. Smith noted that VFC funds cannot be used to purchase vaccine for children covered under the Healthy Families Program, California’s State Child Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). The health plans that contract with the California Healthy Families Program are responsible for reimbursing the costs of the vaccines to the providers. The

TABLE 2 Estimated Vaccination Coverage for the 4:3:1:3* Series Among Children Ages 19 to 35 Months, United States and California, 1996–2000

|

|

Percent |

||||

|

Area |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

|

United States |

76 |

76 |

79 |

78 |

76 |

|

California |

74 |

74 |

76 |

75 |

75 |

|

City of Los Angeles |

75 |

72 |

76 |

76 |

76 |

|

San Diego County |

74 |

78 |

77 |

75 |

76 |

|

City of Santa Clara |

80 |

69 |

84 |

82 |

76 |

|

Rest of state |

72 |

76 |

75 |

74 |

75 |

|

*Four or more doses of DTP, three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine, one or more doses of any measles-containing vaccine, and three or more doses of Hib vaccine SOURCES: CDC, National Immunization Survey (www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage). |

|||||

state also purchases 700,000 doses of influenza vaccine for use by county health departments to help assure the delivery of immunization services to the high-risk population. Dr. Smith noted, however, that the cost of influenza vaccine had more than doubled in a single year, going from $1.80 per dose in 1999 to $4.45 per dose for 2000.

As part of its surveillance activities, the state monitors both immunization coverage rates and immunization exemptions granted for personal beliefs. Immunization rates for 2-year-olds in California are comparable to rates for the nation as a whole (see Table 2 and www.cdc.gov/nip/coverage). The latest data for 2000 from the National Immunization Survey (NIS) show that 75 percent of California’s 2-year-olds are fully immunized for the 4:3:1:3 series, compared with the national average of 74 percent. Preliminary estimates for the 2001–2002 school year indicate that about 1.2 percent of children entering kindergarten were not immunized because of exemptions for their families’ personal beliefs. In some counties, up to 5 percent of children have been exempted. Where exemption rates are high, the state health department is concerned about increased risk for disease outbreaks.

The immunization rates for older adults (ages 65 and over) exceed the national average but still fall short of the national public health goal of 90 percent coverage. Dr. Smith reported that California data for 2000 show that 70 percent of older adults reported having received an influenza vaccination in the previous year. The national rate for 1999 was 67 per

cent (CDC, 2001). For 2000, California also estimates that 61 percent of older adults had ever received a pneumococcal pneumonia vaccination, compared with the national estimate of 54 percent in 1999 (CDC, 2001). Rates in California are lowest for high-risk adults ages 18 to 64 and for African-Americans.

Efforts to sustain and improve immunization coverage include adding varicella to the immunizations required for day care and school entry. Dr. Smith reported that NIS data show that varicella coverage rates for 2-year-olds had reached 76 percent in 2000, up from just 26 percent in 1996– 1997. She expressed concern, however, that the current shortages of DTaP and varicella vaccines might contribute to lower coverage rates. Health plans, which must report their immunization coverage rates as a Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set measure, are also becoming concerned about the impact of vaccine shortages.

Immunization registries can aid in monitoring immunization coverage rates and in efforts to identify children in need of immunization services. Dr. Smith noted that in California registries had begun at the county level and that efforts are now under way to establish regional systems. California has submitted an application for funding from Medicaid to help support registry activities. A workshop participant urged state-level leadership in developing a comprehensive registry to overcome the problem of incomplete and scattered records, which can arise when families move from one community to another.

With California’s large population, the amount of state and federal immunization funding available per child is relatively modest compared with many other states. The state received $18.3 million in federal immunization grant funds for 2001, down from a peak of $36.5 million in 1996. A multiyear approach to federal Section 317 grants, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), would aid the state in maintaining a more stable funding base for its immunization program. Dr. Smith noted that new federal funding for activities related to bioterrorism, some of which will be relevant for the immunization program, may be awarded on a multiyear basis.

California also supports efforts to implement the IOM recommendation for formula-based funding for Section 317 awards. A formula would help clarify the basis for federal funding decisions and is expected to produce a more equitable allocation of funds. In addition, Dr. Smith suggested targeting funds for “pockets of need” and giving greater attention to the implications of new vaccines and immunization recommendations for adolescents and adults. Overall, she urged maintaining an adequate level of funding to help break the “immunization cycle,” with disease outbreaks stimulating rapid but temporary funding increases (Roper, 2000).

LOS ANGELES COUNTY

The immunization financing issues facing Los Angeles County were discussed by Jonathan Fielding, county health officer and director of public health. With a population of 9.5 million and an annual budget of about $460 million, Los Angeles is larger than many states. The county is also exceptionally diverse. About 45 percent of its residents are Hispanic, 31 percent are non-Hispanic white, 12 percent are Asian or Pacific Islander, and 9 percent are African American. English is not the primary language of 49 percent of the county’s residents, and 35 percent are foreign born. Dr. Fielding noted that as many as 100 languages are spoken in Los Angeles. Overall, 22 percent of residents are living in poverty, but among children ages 0 to 4 years, 36 percent are poor. In 1999–2000, 20 percent of children were uninsured, but there is concern that the percentage of uninsured children may increase as a result of the current economic downturn.

Despite these challenges, Los Angeles County’s immunization coverage rates, at about 76 percent for 2-year-olds in 2000, are similar to state and national rates. Rates for children in low-income families are slightly lower, but the difference is not statistically significant. The incidence of vaccine-preventable disease has also been reduced significantly over the past decade, although the number of pertussis cases has increased (see Table 3).

The county’s immunization program receives 30 percent of its funding from the state and 70 percent from federal sources. For 2001, the total amounted to $5.4 million. In addition, the county funds the delivery of immunization services at 49 facilities operated by its Department of Health Services (DHS). However, more than 90 percent of immunizations in Los Angeles County are delivered by about 5,000 private providers. Of this group, about 1,100 participate in VFC.

TABLE 3 Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, Los Angeles County, 1990–2000

|

Year of Onset |

1990 |

1995 |

2000 |

|

Measles |

4,052 |

7 |

5 |

|

Mumps |

102 |

42 |

29 |

|

Rubella |

106 |

3 |

3 |

|

Pertussis |

93 |

103 |

102 |

|

Haemophilus influenzae type B |

208 |

6 |

1 |

|

SOURCE: Los Angeles County Health Department (2002). |

|||

Dr. Fielding outlined serious financial challenges for the county and its immunization efforts. Current funding from state and federal sources is about one-third less than the $8 million available in 1997. This funding decrease has made it necessary to reduce immunization clinic staff and services along with outreach and education activities, including assessments and referrals from WIC4 clinics and the production of health education materials. Further reductions in state funding are expected for 2002 and 2003. In addition, a fiscal crisis for the county means that lost state funding is not likely to be replaced locally, and closure of some facilities where immunization services are provided is expected.

In terms of publicly funded vaccine purchase, Los Angeles County depends heavily on the federal VFC program. For 2001, about 3.4 million doses of vaccine costing $60 million were obtained through VFC. The county purchased an additional 110,000 doses of vaccine, at a cost of $400,000. Dr. Fielding emphasized the challenges facing the county in the future. Substantial increases have already occurred in the cost of some vaccines (i.e., influenza and tetanus and diphtheria toxoids [Td]) and might occur for other vaccines. Moreover, demand for vaccines for adults (e.g., hepatitis A and B and pneumococcal vaccines) is increasing. Those vaccines cannot be obtained through the VFC program (but could be purchased with Section 317 funding, if funds were available).

Dr. Fielding also noted, as Dr. Natalie Smith had, that chronic vaccine shortages are becoming a concern because they pose a risk of reducing immunization coverage rates. Los Angeles DHS facilities have occasionally had to turn people away because requested vaccines were unavailable. In addition, private providers who have not been able to obtain vaccines are looking to the health department to provide those immunizations, even though the health department is subject to the same supply constraints. Referrals also appear to be coming from private providers concerned about inadequate reimbursement for vaccine and immunization services.

The current priorities for the immunization program in Los Angeles include ensuring the availability of free childhood immunizations, developing better programs to serve the children who are hardest to reach, directing additional resources to education and quality assurance activities for the large population of private providers delivering immunization services, and strengthening the immunization registry. Dr. Fielding

noted that resources for provider education and quality assurance are inadequate, even for VFC providers alone. He also emphasized the importance of improving providers’ use of the immunization registry. Not only should they submit data on a regular basis, but they should also check the immunization status of children before giving new doses.

Dr. Fielding identified several general concerns regarding financing for immunization services. Stable funding is needed for planning and sustaining immunization activities, including outreach and education. A more stable vaccine supply is also needed. Other concerns include funding for purchase of adult vaccines and combination vaccines and increased support for immunization infrastructure and immunization registries. Dr. Fielding also highlighted two issues related to private health insurance coverage for immunizations. Clearer guidelines are needed for judging the “medical necessity” of, and therefore coverage for, influenza vaccinations. Also, some employers may be considering a change in the way they offer benefits for preventive health care. Instead of offering coverage for certain services such as immunization, they may offer a fixed-dollar benefit and allow employees to decide how to allocate those benefit dollars. Dr. Fielding expressed concern that such an approach might make it more difficult to align personal and public health priorities related to immunization. He concluded that progress has been made in responding to the IOM recommendations on immunization finance policies and practices, but that growing financial problems such as those facing California and Los Angeles could overtake those gains.

SAN DIEGO COUNTY

Sandra Ross, immunization program coordinator for the San Diego County Health and Human Services Agency, discussed that county’s immunization activities and financing concerns. In San Diego County, an immunization program plan, developed in 1991 following the measles epidemic, is implemented by an extensive community coalition involving more than 150 community agencies and organizations. The health department provides leadership, but outreach efforts are delivered primarily through community partnerships. The broadly based coalition has helped generate political and legislative support for immunization activities. All activities and interventions have been data driven. Some of the activities included in the immunization program are community coverage assessments through telephone surveys and the review of kindergarten and day-care records; community education and outreach, especially immunization assessment and referral activities, such as activities for clients at WIC clinics; development and management of the immunization registry; and assessment of immunization coverage rates and provider

behaviors in public clinics and at private provider sites. Efforts are being made now to expand beyond the original focus on children to address adult immunization needs as well.

Immunization rates for 2-year-olds have risen since the start of the initiative. Estimates for 2000 from the NIS show that 78 percent of children have completed the 4:3:1 series,5 and the county’s own telephone survey puts the level at 86 percent. The annual review of kindergarten records is extensive enough to produce retrospective estimates of immunization rates for 2-year-olds by race and ethnicity, a level of detail not available from the telephone surveys. Those estimates show that coverage rates for 2-year-olds have been highest among white children, ranging from 71 percent in 1992 to 75 percent in 1997. Over the same period, rates among Hispanic children rose steadily from 56 to 70 percent. Rates for Black children, who include both African-American and foreign-born children, have remained the lowest, but rose from 56 percent in 1996 to 68 percent in 1997. Ms. Ross suggested that this increase reflected the results of special focus on the black community. She noted, however, that the outreach worker for that project is no longer available.

The county also conducts a telephone survey to monitor immunization coverage rates among adults ages 65 and over. For 2000, 75 percent had received an influenza vaccination in the previous year, and 69 percent had ever received a pneumococcal vaccination. Only 57 percent of older adults had an up-to-date tetanus immunization.

The annual cost to fully implement San Diego’s immunization program was originally estimated at $4 million, but actual funding has approached that level for only one year. For 2001, the program had $2.56 million from the state and $720,000 from the county, but future funding levels are uncertain. Funding reductions following the peak level in 1996 has meant that only some of the planned and implemented activities could be sustained. Furthermore, lack of stable and predictable funding has limited the establishment of regular full-time positions at the health department. As a result, the immunization program now relies on about 50 contract staff, but that approach has put the county in conflict with the employee union.

In terms of services, the immunization program currently maintains free walk-in immunization services at more than 40 sites, and over 150 private providers are participating in VFC. Ms. Ross noted that public health clinics are often used on a one-time basis by people who are

transitioning between health plans or seeking a regular health care provider. Systematic assessments of providers’ immunization records are conducted on an annual basis using CDC’s AFIX (Assessment, Feedback, Incentives, eXchange) strategy. The assessment program covers 13 public health clinics, 36 community health centers, and 132 private practices. Coverage rates have improved in all settings since the AFIX reviews began. To deliver additional training to providers and their staffs, the immunization program has begun to rely on videotapes and other distance-learning resources, which minimize the need for either instructors or participants to travel to attend educational programs.

The immunization program also manages the county’s immunization registry. Provider participation in the registry is being adversely affected by associated costs, however. Telephone charges for continuous access to the registry system have been as high as $1,000 per month for some providers. To overcome this problem, a web-based access system is being developed. Ms. Ross also observed that private providers have less money from managed care contracts than in the past to cover the cost of office operations, which includes data entry for the immunization registry. The immunization program lacks the resources to assist providers with data entry.

Ms. Ross noted that the immunization coalition has found that the community accepts the value of immunization and that parents rely on their doctors to provide immunizations when they are needed. As a result, outreach activities in San Diego County are focused on helping clinics and private providers improve immunization coverage among their patient populations rather than on community education. Immunization assessment services are available to the public by telephone, from the immunization coalition’s website (www.immunization-sd.org), and through coalition partners that provide record assessment and referrals.

WIC clinics have been conducting immunization assessments for their clients, but it is proving difficult to capture that activity in the immunization registry or to gain access to the clinic records to evaluate the effectiveness of the WIC assessments without federal approval. An immunization assessment program is also being tried for clients of CalWorks, the state welfare program. The health department is training CalWorks staff to conduct immunization assessments and to use the immunization registry. The pilot looks very effective, but the continuation of those activities will depend on the availability of immunization program funds.

OBSERVATIONS FROM IOM CASE STUDIES

Los Angeles and San Diego counties were the subject of one of the case studies for the IOM review of immunization finance policies and

practices. Gerry Fairbrother, from the New York Academy of Medicine and an author of the Los Angeles–San Diego case study, discussed key findings. As counties, both Los Angeles and San Diego have sizable populations, with Los Angeles being larger than five of the seven case-study states. In both counties, at least 90 percent of immunizations are given by private providers. Some aspects of the county-level immunization programs are shaped by state policies. California, in contrast to some states, does not mandate that private health insurance plans provide “first-dollar” coverage for immunizations and does not have a “universal purchase” policy that makes required vaccines available without charge to all children in the state.

California’s experience with federal immunization infrastructure funding through the Section 317 program mirrored that of other states: A rapid increase in funding was followed by both an increase in spending and repeated carryover of a portion of each year’s award. Funding, spending, and fund carryover all peaked in the mid-1990s, then rapidly declined. Most of the funds carried over by California had been spent by 1997. Los Angeles and San Diego counties followed a similar course of rising infrastructure funding that peaked in mid-decade. Dr. Fairbrother pointed out, however, that even though the state could carry over funds from year to year, the counties could not and therefore had even less assurance of stable funding.

As Dr. Fielding and Ms. Ross had described, the expansion of immunization program activities that occurred during the period of increasing funding has been followed by program cutbacks as funding has declined. Dr. Fairbrother highlighted the impact of the cutbacks on changes in the delivery of immunization services within the WIC nutrition program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The WIC program serves a large portion of the population of infants and young children; 45 percent of infants nationally and 70 percent in Los Angeles and San Diego counties are eligible for WIC services (Fairbrother et al., 2000b). In the 1990s, many local WIC programs elected to add immunization assessment and referral activities, usually with supplemental funding from local immunization programs. At the national level, reduced funding for immunization efforts led to tensions with the WIC programs. Many immunization programs cut their support for the immunization assessment and referral activities, but expectations for continued collaboration with WIC clinics remained.6

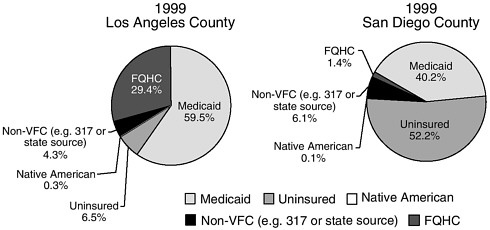

FIGURE 3 Sources of eligibility for children participating in the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program in Los Angeles and San Diego Counties, 1999. Note: FQHC represents vaccines distributed to children who receive their immunizations in federally qualified health centers. Source: Fairbrother et al., 2000b.

During the 1990s, immunization programs in California and elsewhere were also affected by the introduction of VFC and SCHIP and the growth of Medicaid managed care programs, which helped shift the delivery of most immunization services to private providers. However, VFC increased the availability of publicly purchased vaccine. The case study showed that Los Angeles and San Diego differ in terms of how publicly purchased vaccine is used. In Los Angeles, about 60 percent of the children who receive such vaccine do so through Medicaid and only about 7 percent are uninsured. In San Diego, 40 percent of the children receiving publicly purchased vaccine are on Medicaid and 52 percent are uninsured. As Dr. Natalie Smith noted, children enrolled in the Healthy Families Program are not eligible for vaccine obtained through VFC. This creates an added burden for providers participating in the Healthy Families Program because they must order and track that vaccine separately from the VFC vaccine. Moreover, provider payments for immunization services are relatively low because they were set based on an expectation of other funding for vaccine purchase.

The IOM case studies for the California counties and other states showed the problems that unpredictable federal funding posed for state and local efforts to plan and undertake certain activities for their immunization programs. They also demonstrated that while health departments were playing a smaller role in the direct delivery of immunization ser-

vices, they needed new policy tools—such as information management systems and collaborative partnerships with health plans and private providers—to manage their growing and sometimes unfamiliar responsibilities for oversight of the delivery of those services.

DISCUSSION

Questions and comments from workshop participants touched on various concerns for the immunization programs of the state and of local health departments. Given the likely constraints on future federal and state funding for immunization infrastructure activities, the prospects for county-level funding were discussed. In both Los Angeles and San Diego, however, county funding is expected to decline from current levels. For example, San Diego County may discontinue its support for the immunization registry. In Los Angeles, cuts are expected for the DHS facilities and staff where the health department provides immunization services.

Dr. Fielding commented on the challenges of meeting the immunization needs of the highly diverse population of Los Angeles. He noted that the county lacks good data on the full range of ethnic subgroups being served. He emphasized, however, that keeping immunization connected to other aspects of health care is a priority and that one approach taken by the health department has been to establish service contracts with several clinics based in particular ethnic communities. Those clinics, which have 700,000 visits per year, help provide access to culturally competent health care staff. The ethnic diversity in the county is so great, however, that the health department cannot afford to produce community education materials in all relevant languages.

Also discussed was the experience at the state and local levels in working with private providers on quality assurance for immunization services. To detect and correct problems such as improper vaccine storage and handling practices, the state has been working in partnership with the California chapters of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians to visit about 1,000 VFC physician practices each year. The state also works with managed care organizations to address quality improvement issues. Additional oversight and training occur at the local level.

A workshop participant encouraged efforts to reduce the administrative burden associated with data entry for immunization registries. Less burdensome data entry might increase provider participation. A workshop participant noted that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has awarded a grant to the L.A. Care health plan to assess the information system needs of its participating providers.