1

Workshop Summary

David Hill

ASSESSING THE EVIDENCE

Cary Sneider, chair of the Steering Committee and vice president for programs at the Museum of Science in Boston, opened the workshop by stating its purpose: to determine whether the National Science Education Standards (NSES) have influenced the U.S. education system, and if so, what that influence has been. “This is absolutely essential,” he told the participants, “if we are to know how to go forward in our collective efforts to improve or, in some cases, overhaul the science education system.”

Sneider urged the attendees to “think of today as a learning event…. We are all the students.”

In that vein, Sneider asked each participant to write down what he or she considered to be the greatest influence of the NSES and then compare the notes with the person in the next seat. Sneider then asked for volunteers to share their ideas with the entire group.

One workshop participant asserted that the NSES have provided a “vision statement” to be used as a starting point for other organizations concerned with the improvement of science education. In addition, the NSES provide states with a roadmap to use when creating their own standards. Another participant pointed out that the NSES have “raised the debate” regarding the issue of science standards. One attendee cited the increased emphasis on inquiry in the science curriculum. Another pointed to the NSES’s “strong influence” on professional development for teachers.

Sneider proceeded to introduce the authors, whose papers were commissioned by the National Research Council (NRC) in preparation for the workshop. James Ellis, of the University of Kansas, investigated the influence of the NSES on the science curriculum. Jonathan Supovitz, of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education at the University of Pennsylvania, researched the influence of the NSES on the professional development system. Norman Webb and Sarah Mason, of the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, investigated the influence of the NSES on assessment and accountability. A team from Horizon Research, Inc., led by Iris Weiss and Sean Smith, looked at the influence of the NSES on teachers and teaching practice. Charles

Anderson, of Michigan State University, researched the influence of the Standards on student achievement.

In the fall of 2001, NRC staff searched journals published from 1993 to the present, bibliographic databases, and Web sites for relevant studies using a list of 61 key words and phrases. The hundreds of documents identified were screened using explicit inclusion criteria, e.g., studies focusing on the implementation or impact of the National Science Education Standards and/or the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Benchmarks for Science Literacy. Copies of the resulting 245 documents were provided to the commissioned authors, and authors added additional documents with which they were familiar or that were released in the months following the search.

The researchers analyzed and evaluated the documents relevant to their topics, produced bibliographic annotations, and synthesized the findings from the body of research, drawing conclusions and giving suggestions for future research.

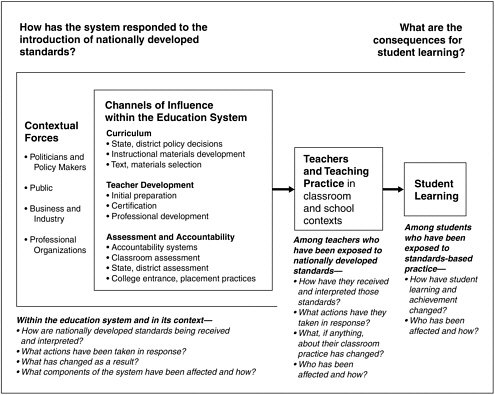

Sneider explained that the papers were organized under a framework developed by the NRC’s Committee on Understanding the Influence of Standards in K-12 Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education, chaired by Iris Weiss, of Horizon Research, Inc. (see Figure 1-1).

“It is a lovely scheme to think about the influence of standards,” Sneider said, “whether we are talking about mathematics, technology, or science standards. You will notice on the right there is a box that says, ‘Student Learning.’ That is what the standards are for. If they don’t have an effect on student learning, then any influence they may have had is irrelevant…. How do we have impact on students? Well, primarily through their teachers.”

The Framework identified three major channels of influence on teachers and teaching: the curriculum, which includes instructional materials as well as the policy decisions leading to state and district standards and the selection of those materials; teacher professional development, which includes both pre-service and in-service training; and assessment and accountability, which includes accountability systems as well as classroom, district, and state assessments.

“All of this occurs,” Sneider explained, “within a larger context. The larger context is political and involves politicians and policy makers. It involves members of the general public and their perceptions of the system. It involves business and industry as well as professional organizations. So the way we have organized and assigned the authors to analyze the research is in these five areas: learning; teachers and teaching practice; curriculum; teacher development; and assessment and accountability.”

The Curriculum

Ellis began his presentation by explaining that the body of research on the influence of the NSES on the science curriculum isn’t “solid” and consists mostly of surveys and “philosophical papers.” However, he added that he feels “pretty confident to say that states are moving towards the vision in the National Science Education Standards.”

FIGURE 1-1 A framework for investigating the influence of nationally developed standards for mathematics, science, and technology education.

SOURCE: NRC (2002).

In his paper,1 Ellis distinguishes between the “intended curriculum,” the “enacted curriculum,” and the “assessed curriculum.”

The first, he explained, is “a statement of goals and standards that defines the content to be learned and the structure, sequence, and presentation of that content.” Those standards are defined by national guidelines such as the NSES, by state standards and curriculum frameworks, by local standards and curriculum frameworks, and by publishers of instructional materials.

The NSES, he pointed out, target the intended curriculum as their primary sphere of influence.

The intended curriculum, he asserted, is interpreted by teachers, administrators, parents, and students to create the enacted curriculum— or what actually is taught in the classroom. The assessed curriculum comprises that portion of

|

1 |

The full research review by James D. Ellis is in Chapter 2 of this publication. |

the curriculum “for which current measurement tools and procedures are available to provide valid and reliable information about student outcomes.”

Ellis found evidence that the NSES have influenced all three aspects of the curriculum. “The influence of the NSES on the meaning of a quality education in science at the national level has been extraordinary,” he noted, adding that “decisions about the science curriculum, however, are not made, for the most part, at the national level.” Based on a review of surveys, Ellis found some evidence of influence of the NSES on textbooks, which he calls “the de facto curriculum.”

“Even a cursory look at textbooks published in the past five years,” Ellis noted, “provides evidence that textbook publishers are acknowledging the influence of the NSES. Most provide a matrix of alignment of the content in their text with the NSES.” The research literature reviewed by Ellis, however, provided little evidence about the degree of influence of the NSES on textbook programs.

According to the research, progress is being made toward providing models of “standards-based” instructional materials in science. However, the “vast majority” of materials being used by teachers fall short of those models and are not in line with the NSES. In addition, the adoption and use of currently available “high-quality, standards-based” instructional materials may be a “significant barrier” to realization of the science education envisioned in the NSES (see also Chapter 2).

At the workshop, Ellis acknowledged the need for “more innovative curriculum design” in the sciences as well as a diversity of models and approaches “so we can find out which ones work in which settings. I personally don’t believe that one design is going to work in all settings for urban, suburban, and rural students….”

Ellis also urged the development of “consumer reports” that would outline the strengths and weaknesses of curriculum models. “I think we need to help schools and states,” he said, “learn how to make good decisions, and we need to work on looking at how we enact high-quality, standards-based curricula and the approaches and procedures we go through in doing that.”

Professional Development

In looking at the influence of the NSES on professional development, Supovitz divided the research into three categories: the evidence of influence of the NSES on policies and policy systems related to professional development, which he characterized as “minimal”; the evidence of influence of the NSES on the pre-service delivery system, which he characterized as “thin”; and the evidence of influence of the NSES on the in-service professional development delivery system, which he characterized as “substantial.”

In his paper,2 Supovitz characterizes the overall influence of the NSES on professional development as “uneven.”

“On the one hand,” he asserted, “there seems to be substantial evidence that the National Science Education Standards have influenced a

|

2 |

The full research review by Jonathan A. Supovitz is in Chapter 3 of this publication. |

broad swath of in-service professional development programs. Most of the evidence points toward the influence of the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Title II of the old Elementary and Secondary Education Act, the Eisenhower program.” While it is difficult to estimate how many teachers have received standards-based science professional development, “the large scope of both the Eisenhower and NSF programs suggest that this influence has been extensive, although still only accounting for a small proportion of the national population of teachers of science.”

At the workshop, Supovitz cautioned that, because reform-oriented in-service programs tend to receive more scrutiny by researchers than those that are more traditional, seeing the “big picture” can be difficult. The overall state of professional development, he warned, may not be as promising as studies of some of the specific programs suggest.

There is less evidence that the NSES have influenced the state and district policy structures that leverage more fundamental changes in such areas as professional development standards, teacher licensing, or re-certification requirements, Supovitz noted in his paper. Further, there is little evidence that colleges and universities have substantially changed their practices and programs since the NSES were introduced.

Overall, Supovitz noted, the evidence base of the influence of the NSES on pre-service professional development is “extremely thin.” What few studies that do exist, however, lead to the impression that the NSES have not made substantial inroads into changing the way teachers are prepared for the classroom.

Supovitz added that “one cannot help but to have the impression that the science standards have focused the conversation and contributed to a freshly critical evaluation of the systems and policies that prepare and support teachers to deliver the kinds of instruction advocated by the science standards. What is lacking is empirical evidence that the science standards have had a deep influence on the structures and systems that shape professional development in this country.”

In his paper, Supovitz calls for more—and better—research in order to develop a more coordinated body of evidence regarding the influence of the NSES on professional development.

“Building a strong evidence base,” he writes, “requires multiple examples of quality research employing appropriate methods that together provide confirmatory findings. The evidence examined in this study suggests that the current research base is of variable quality and provides too few reinforcing results.” Despite a number of “high quality studies,” he noted, “the collective picture is largely idiosyncratic and of uneven quality.”

Assessment and Accountability

Webb began his presentation by acknowledging his co-author, Sarah Mason, who did not attend the workshop. Webb explained that he and Mason found very few studies that have looked directly at the question of whether the NSES have influenced assessment and accountability. “I think it is a legitimate question to look at,” he said, “but a lot of people have not really studied it.”

In their paper,3 Webb and Mason cite two case studies of reform, one in a large city and the other in a state, documenting that those who wrote the district and state content standards referred to the NSES and AAAS Benchmarks. “It is reasonable to infer,” they write, “that these cases are not unusual and that other states and districts took advantage of these documents if available at the time they engaged in developing the standards…. It is reasonable that states would also attend to the Standards and Benchmarks over time as they revise standards and refine their accountability and assessment systems.”

They also point out that although a clear link could not be established between assessment and accountability systems used by states and districts and the Standards and the Benchmarks, “there is evidence that assessment and accountability systems do influence teachers’ classroom practices and student learning.” What is needed, they argue, is a comprehensive study of policies in all 50 states that would reveal linkages between science standards, science assessment, and science accountability. Among Webb and Mason’s other findings:

-

Accountability systems are complex, fluid, and undergoing significant change.

-

Assessments influenced by the Standards will be different from traditional assessments.

-

The number of states assessing in science has increased from 13 to 33, but there has also been some retrenchment in using alternative assessments.

-

A likely influence will be evident through the degree that the Standards, state standards, and assessments are aligned.

Webb called for more research, including comprehensive studies to determine links between state policies and the NSES, assessments, and accountability, as well as multi-component alignment studies to determine how standards, assessments, and accountability systems are working in concert.

Teachers and Teaching Practice

Four questions guided Horizon’s research,4 according to Weiss and Smith: What are teachers’ attitudes toward the NSES? How prepared are teachers to implement the NSES? What science content is being taught in the schools? And how is science being taught, and do those approaches align with the vision set forth in the standards?

Then, they asked three more questions: What is the current national status of science education? What changes have occurred as a result of the NSES? Can we trace the influence of the NSES on those changes?

Smith, who spoke first, reported that secondary teachers are more likely than elementary teachers to be familiar with the NSES. However, among teachers who indicated familiarity with the standards, approximately two-thirds at every grade range report agreeing or strongly agreeing with the vision of science education described in the NSES.

In addition, a variety of interventions attempting to align teachers’ attitudes and beliefs with

the NSES have been successful. “Professional development,” Smith said, “often has an influence on how much teachers agree with the NSES” and how prepared they feel to use them.

The Horizon authors found that many teachers, especially in the lower grades, lack the necessary training to teach the content recommended in the NSES. In contrast, teachers in general feel prepared to implement the pedagogies recommended in the NSES.

Regarding what is being taught in the schools, Smith admitted that little is known about what actually goes on in the classroom. One reason is that little research has been done nationally on the influence of the NSES on the enacted curriculum. However, “if you look at teachers who say they are familiar with the NSES, they are also more likely to say that they emphasize content objectives that are aligned with the NSES.”

Looking at how science is being taught across the country, the Horizon team found that little has actually changed since the introduction of the NSES. “There is a slight reduction in lecture,” Weiss said, “as well as in the use of textbook and worksheet problems, and a reduction in the number of students reading science textbooks during class. But little to no change in the use of hands-on or inquiry activities.”

Smith and his colleagues concluded that the preparedness of teachers for standards-based science instruction is a “major” issue. “Areas of concern,” they write, “include inadequate content preparedness, and inadequate preparation to select and use instructional strategies for standards-based science instruction. Teachers who participate in standards-based professional development often report increased preparedness and increased use of standards-based practices, such as taking students’ prior conceptions into account when planning and implementing science instruction. However, classroom observations reveal a wide range of quality of implementation among those teachers.”

Weiss began her remarks by restating a point made by Jonathan Supovitz: reform-oriented education programs tend to be studied more than others and are more likely to be published if the conclusions are positive, resulting in a bias toward positive reporting. Consequently, programs that are scrutinized by researchers tend to look much better than teaching in general.

When teachers try to implement standards-based practices in their classrooms, she added, many tend to grab at certain features while omitting others. “The pedagogy is what seems to be most salient to teachers,” she said. “So what we have is teachers using hands-on [lessons], using cooperative learning” at the expense of “teaching for understanding.”

“One possibility,” she said, “is it just means that change takes time, and that the grabbing at features and the blending in of the new and the traditional may be on the road to a healthier Hegelian synthesis type of thing.”

On the other hand, she added, it may be simply that there is a “healthy skepticism” on the part of teachers when it comes to reform.

Another problem, she said, is that the content standards themselves are too daunting. “My personal belief,” she said, “is that you cannot teach all of the content embedded in the NSES or the Benchmarks in the 13 years we have available to us, using the pedagogies we are recommending to teachers. So, we force them to make those choices.”

One factor, Weiss said, may be the increasing influence of state and district tests. Anecdotal evidence tells us that teachers believe in the standards. “On the other hand,” she said, “they and we are held accountable for the state and district tests, which in many cases are not standards-based.”

Weiss expressed the need for better research, based on nationally representative samples, on the influence of the NSES on teachers and teaching. Much of the existing literature on teacher preparedness is based on the self-reporting of teachers, which is problematic. “We found frequent contradictions in the literature between self-report and observed practice,” Weiss noted.

“A major question that remains,” she and her colleagues conclude in their paper, “is what science is actually being taught in the nation’s K-12 classrooms. No comprehensive picture of the science content that is actually delivered to students exists. This lack of information on what science is being taught in classrooms, both before the NSES and since, makes it very difficult to assess the extent of influence of the NSES on teaching practice.”

Student Achievement

Anderson, in researching the influence of the NSES on student achievement, tried to answer two questions posed in the Framework (Figure 1-1): Among students who have been exposed to standards-based practice, how have their learning and achievement changed? Who has been affected, and how?

Before answering those questions, Anderson considered an alternative question: Do standards really matter? In his paper,5 Anderson cites the work of Bruce Biddle, of the University of Missouri-Columbia, who has argued that resources, not standards, are much more important when it comes to student achievement. “Improving achievement,” Anderson asserts, “is about making resources available to children and to their teachers, not about setting standards.”

At the workshop, Anderson pointed out that there is a tendency to think of the NSES as a set of rules or guidelines to follow, and if teachers follow those rules, student achievement will improve. But things are not so simple. Teachers are unlikely to adhere to the practices advocated in standards unless they have good curriculum materials and sufficient in-service education.

“So another way of thinking of the NSES,” he said, “is to say, ‘These aren’t really rules at all in a typical sense. They are investment guidelines.’ ”

Anderson looked at two types of studies: those that characterized standards as rules, and those that characterized standards as investments, such as the NSF-funded systemic initiatives. Overall, both types of studies provided weak support for a conclusion that standards have improved student achievement. At the same time, the studies provided no support for the opposite conclusion: that standards have had a negative impact on student achievement.

In addition, he notes in his paper, “if you look at the evidence concerning the achievement gap,

|

5 |

The full research review by Charles W. Anderson is in Chapter 6 of this publication. |

there really is no evidence that standards-based investment and standards-based practice is affecting the achievement gap between African American and/or Hispanic and European American students for better or worse.”

In other words, the evidence that the NSES have had an impact on student achievement is inconclusive. “The evidence that is available,” Anderson writes in his paper, “generally shows that investment in standards-based practices or the presence of teaching practices has a modest positive impact on student learning.” It would be nice, he adds, to have “definitive, data-based answers” to these questions. “Unfortunately, that will never happen. As our inquiry framework suggests, the standards lay out an expensive, long-term program for systemic change in our schools. We have just begun the design work in curriculum, professional development, and assessment that will be necessary to enact teaching practices consistent with the standards, so the data reported in this chapter are preliminary at best.”

At the workshop, Anderson noted that he also looked at several case studies that “tended to look very specifically at particular teaching practices and very specifically at particular student learning outcomes.” Some of those studies showed a convincing relationship between teaching practices and student learning. Anderson called for more case studies and design experiments to help us evaluate and improve upon standards-based work—to see “what is reasonable, what is realistic, how they fit together in kids’ minds….” Such studies, he said, are also useful in designing the particular systems and practices that enact standards-based teaching.

Other studies showed a positive connection between teachers’ participation in professional development or use of certain curricular materials and student achievement. “The longer the chains of inference and causation, though,” he notes in his paper, “the less certain the results.”

THE WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS RESPOND

Following the authors’ presentations, Cary Sneider solicited questions from the workshop participants.

One attendee made several points, beginning with what he called a “potentially controversial statement,” that the NSES are more of a wish list of what experts think should be taught rather than a set of standards based on the research of what we know students can do.

His second point referred to the Framework (Figure 1-1), which he proposed changing to a “feedback loop” to bring what we know about student learning back to the standards themselves to inform revisions and improvements of those standards. The questioner wanted to know if the authors thought that made sense.

In response, Iris Weiss explained that the diagram wasn’t an attempt to illustrate the system as it operates but rather an attempt to show influence, namely, the influence of the NSES on student learning. “I agree with you,” she said, “that we need to look at student learning and all the other pieces and think about this as an approach to changing the system,” she said, “but that is a research task….”

Charles Anderson, however, asserted that

the Framework is, in fact, “far too good a representation” of how the system really works. “There are a bunch of people in Washington,” he said, “who try to influence a bunch of people in the schools, and they don’t listen a whole lot before they do it, and they don’t look very carefully at the research before they do it.”

Another questioner asked Norman Webb about the information he presented from the 2000 state National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data in mathematics. It showed that when teachers’ knowledge of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) standards in states with no or with low-stakes assessments is compared to teachers’ knowledge of NCTM standards in states with high-stakes assessments, the first group of teachers reported being more knowledgeable about the NCTM standards than those in the second group. The questioner wanted to know if Webb had looked at whether any of the states with high-stakes tests used standards that were based on those published by the NCTM.

In response, Webb said that based on an analysis of mathematics standards in 34 states done for Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) in 1997, it is fair to say that at least some states with high-stakes testing have standards that were influenced by the national standards, but we do not know if all of those states do.

Another participant asked if there is not a need to substantially improve the way research is conducted on how to assess whether the standards are having an impact on teaching and learning.

Webb called the point valid, but noted that good assessments do exist. But, he added, “assessment is very complex,” hard to do on a large scale, and costly, and most states do not want to spend a lot of money on it.

Jonathan Supovitz added that large-scale assessments often get “muddied up” by “the policy incentives and the economics that go into the construction of the assessment.” Conducting smaller, more carefully designed assessments may yield better, more accurate results, he said.

Another participant asked if Supovitz knew what percentage of in-service professional development could be considered “reform-oriented.” Supovitz replied that, based on the cross-State Systemic Initiative (SSI) research, large numbers of teachers were involved in the SSIs, but the numbers were relatively small compared with the overall number of teachers in the states. “So, if you can generalize from that sketchy piece of information,” he added, “then you could say that the effects [of the NSES-oriented professional development] are probably overstated because you are looking at the areas where reform is going on.”

Weiss added that her recollection of the study by Garet et al. was that “the higher education piece of the Eisenhower Fund-supported professional development program fits more with the criteria for professional development as advocated by the NSES than when the districts use the money on their own. That’s nationally representative data. It is based on surveys, but it is a pretty carefully done study.”

Anderson added that, based on the available data, it is difficult to say how much influence the NSES have had on pre-service teacher education. “I know we teach our courses differently from the way we taught them four or

five years ago,” he said, “but not in ways that show up in the course titles.”

THE STEERING COMMITTEE MEMBERS RESPOND

After a short break, Sneider introduced the members of the Steering Committee present at the workshop: Ronald Anderson, of the School of Education at the University of Colorado; Enriqueta (Queta) Bond, of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; James Gallagher, of Michigan State University; and Brian Stecher, of the RAND Corporation. (Rolf Blank, of the Council of Chief State School Officers, was not present.)

Sneider praised the committee members for their role in planning the workshop. He asked each member to share his or her thoughts about the authors’ findings.

Speaking first, Anderson began by commenting on the Framework for Investigating the Influence of Nationally Developed Standards for Mathematics, Science and Technology Education (Figure 1-1). “I would like to note,” he said, “that a systems person would almost be sure to say that this is a loosely coupled system…. I think we need to note that it is a very ‘squishy’ kind of system. When you push one place, you are not quite sure where it is going to come out.”

With that in mind, Anderson tried to find a “key leverage point” as he read the papers. That point, he concluded, was the role of the teacher. “So, the question then is, How do you influence the teacher? …You have got to look closely at what the research has to say about teachers and what is involved in changing them and how you reform education in general, with teachers being part of that.” Specifically, Anderson noted that teachers’ values and beliefs are key elements, “and unless something is happening that influences the teachers’ values and beliefs, not much of a change is going to take place.”

Further, such reforms generally occur in a collaborative work context, “where people interact with each other and they wrestle with the real problems of teaching and how they are going to change things,” he said.

Bond stated that, in reading the papers, she was reassured that the NSES have been “a powerful policy force for making investments in science, math, and technology education and that the preliminary evidence is pretty good.” The NSES, she added, are having a “substantial influence” on curriculum development and teacher preparation. “The bottom line, though,” she said, “is that there have been only modest gains in student performance as a result of all the work that has taken place.” Therefore, she noted, we need to focus more on long-term investments.

Bond agreed with Charles Anderson’s recommendations for further research “to better understand what works in improving student performance and closing that gap.”

Gallagher began his remarks by recalling a bumper sticker he once saw on the back of a pickup truck. It said, “Subvert the Dominant Paradigm.” And that, he added, is the goal of the NSES.

“We are trying to change the paradigm of science teaching,” he said. One feature of the old paradigm, he asserted, is to teach some—but not all—students. “We do pretty well with 20 percent of the students,” he said, “maybe less than that, but we certainly don’t have a good handle on

how to teach a wide range of our students science effectively.”

Another feature of the dominant paradigm, he added, is the emphasis on content coverage and memorization. The NSES, however, are based on a different model for science teaching. It is a broader vision that emphasizes teaching for understanding. “We are trying to bring about a huge cultural change,” Gallagher said, “and that is not going to be an easy thing to achieve. We have to recognize that it is going to be a long and slow process.” One issue that needs attention, he said, is the amount of content in the science curriculum. As a result of the standards, many states are now calling for an increase in the amount of content. “[But] less is better,” Gallagher said. In Japan, for example, the national curriculum has been pared down over the last 15 years, so that it now contains 50 percent less material than it did before 1985. “We have to come to grips with that particular issue,” Gallagher said, “and we haven’t talked about it at all.”

Stecher, too, referred to the Framework (Figure 1-1) and talked about the “contextual forces” that have influenced the educational system. Those forces include politicians and policy makers, the public, business and industry leaders, and professional organizations.

“There is a sea change going on now in the nature of the educational context,” he said. “The standards and the research that we have looked at were done during a time in which this sort of top-down view of dissemination made sense.” The federal government, for example, was expected to play a large role. Now, however, he said, “we are moving into an era in which in theory the direction will come from the bottom. The arrows will go the other way, and the leverage point will probably be the assessment box more than anything else.”

Because of that sea change, Stecher added, it was unclear how applicable the research from the last seven or eight years is in light of “the new, more bottom-up local flexibility model of school reform.”

Sneider thanked the members of the Steering Committee and then made several points of his own: the common themes among the NSES, the AAAS Benchmarks, and other related documents set forth a vision of what science education should be; the NSES themselves must continue to be scrutinized over time; and improvements must be made based on what is learned from implementation in the classroom.

SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS

Next, Sneider posed two questions to the workshop participants: What are the implications of this research for policy and practice? And what are the most important researchable questions that still need to be answered?

The attendees were divided into six breakout groups. Sneider asked groups A, B, and C to answer the first question and groups D, E, and F to answer the second question. Each group was joined by a facilitator—a steering committee member—to make sure the participants stayed on task. He asked the facilitators to begin with a brainstorming session in order to get as many ideas as possible. Sneider explained that each breakout room was equipped with a word processor and projected screen, and asked each group

to appoint someone to record the ideas, edit that record with input from the entire group, and then present the group’s ideas to all once the participants were reassembled. Sneider asked the authors to serve as resources to all groups, circulating, listening, and answering questions, as needed.

After more than two hours of discussion, the participants reconvened, and a spokesperson for each group briefly presented its findings and recommendations.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Gerry Wheeler, executive director of the National Science Teachers Association, spoke on behalf of Group A, which grappled with the first question. He and his colleagues agreed that, regarding the curriculum, more direct focus on process is needed. Also, they wanted to know more about teachers’ values and beliefs. “Do they really believe all students can learn?” Wheeler asked.

He pointed out the need to trust “teacher-based, classroom-based assessments” and to fold them into large-scale assessment efforts. “If we’re going to measure the impact [of the NSES] on student outcomes,” he said, “we will have to find some way of agreeing on the measure. There has to be a standard of measure that’s broader than the science standards themselves.”

Regarding teachers and teaching, Group A concluded the following:

-

It is impossible to teach everything in the NSES.

-

More case studies on the teaching of science are needed.

-

The practice of “layering” NSES-based practices onto traditional practices, or selectively using certain features from the NSES, may not be a bad thing. “We need to know how that occurs,” Wheeler said. “We need to stop bad-mouthing it and learn more about it.”

Group A also raised the possibility that the inquiry-based pedagogy advocated by the NSES may not produce the desired student performance. “We felt that more research is needed on this issue,” Wheeler said.

Juanita Clay-Chambers, of the Detroit Public Schools, spoke for Group B. She urged caution when drawing implications from the research presented at the workshop. The research, she said, was “not substantive enough” to lead to major conclusions. “We need to stay the course,” she said, “to provide more time for us to take a look and get some stability in this whole process.”

There is an imperative, she added, for more focused research, as well as research that is linked to policy and to practice. It must become more systematic and standardized regarding the questions to be addressed. Also, we need more integrated work that looks at the different components in relation to one another, not in isolation from one another. “To the extent that we can be clear about what those big-issue questions are,” she said, “we need to include these in our policy and funding initiatives.”

In order to get more meaningful data, she said, researchers must look into “smaller boxes.” Large-scale, globally designed studies often result in “messy,” unusable data. Obtaining funding for small-scale studies is difficult, how

ever. It is imperative that funding agencies address this need, she said.

Group B also noted the conflict between high-stakes testing and standards-aligned practice. More work is needed, Clay-Chambers said, to help develop assessment tools that support standards-based teaching practice.

Regarding the issue of professional development, Clay-Chambers indicated a need to explore the mechanisms that can be used for influencing changes in pre-service teacher education. She mentioned several organizations—including the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards and the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education—but added that others are needed. Such organizations, she said, could offer pre-service teachers incentives for getting additional training within their disciplines—for example, state certification rules could influence this.

More research is needed, she said, to determine the effectiveness of in-service professional development activities “across the continuum,” including activities like lesson studies and action research, particularly “as these activities relate to the desired outcomes.”

Diane Jones, of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, represented Group C. She and her colleagues looked at the issue of funding. How are resources for research allocated within a limited budget? And what effect does that have on the results? Is the research design too narrowly focused on those areas where funding has been historically strong?

“If you don’t have funding,” Jones said, “you probably can’t publish, and so are we missing research just because ideas didn’t get funded along the way?”

Group C also questioned whether current assessment tools are adequately measuring state and district goals. Jones and her colleagues raised several questions related to assessment and accountability: Are we willing to fund the development of assessment tools at all levels from the classroom on up? Is it appropriate to use a single assessment tool for both assessment and accountability or for the evaluation of students, schools, and districts?

The word “reform” itself, Jones said, has become too loaded. “How can we help policy makers, the public, and even educators understand what the goals of reform really are?” she asked. “Do we need to reconceptualize the entire system? Are we looking for a ‘one size fits all’ solution to the current problems?” Are there adequate financial investments in utilizing the standards to raise the performance of all students (top, average, and underperforming)?

Unanswered Questions

Jeanne Rose Century, of Education Development Center, Inc., represented Group D, the first of three groups that grappled with the second question: What are the most important researchable questions that still need to be answered?

Century and her colleagues cited the need for more experimental and quasi-experimental research on the relationship between standards-based instruction and student outcomes among different student populations, including different ethnic, socioeconomic, and demographic groups and their subgroups.

They also posed a broad question: What does it actually take to achieve standards-based instruction and learning in the classroom? That question led to several subquestions: How do the

NSES look when fully operational? What mechanisms can education leaders use for better understanding of the actual status of instruction? What are some of the constraints on reform that are changeable, and how can they be changed? How can reformers work within the constraints that cannot be changed? Have the NSES influenced the content-preparation courses for pre-service teachers? How can we better support content knowledge of teachers in the service of inquiry teaching? How much content do teachers at different levels need? Is there an ideal or preferred sequence of the acquisition of teaching skills and/or knowledge?

Century also expressed the need for more research on “going to scale” with science-education reforms. What does it take for an individual teacher to change the way he or she teaches science? What does it take for an education system to change? And, what are the best mechanisms for researching the culture of education systems at various levels so that we can best adapt and/or target reforms?

Brian Drayton, of TERC, spoke on behalf of Group E. He and his colleagues compiled a list of more than 25 questions that still need to be answered, but they narrowed those down to the most essential:

-

Would a more focused curriculum lead to better learning?

-

Regarding the curriculum, is less more? What is the evidence?

-

Does the vision of science education represented by the NSES match that of teachers, the public, employers, etc.?

-

Do inquiry and critical thinking improve scores on typical assessments across the curriculum?

-

What do standards mean to administrators and teachers?

-

How do we know what students know?

-

Could a standards-based, high-stakes test have a positive effect on teaching and learning?

Representing Group F was Jennifer Cartier, of the National Center for Improving Student Learning and Achievement in Mathematics and Science. Cartier explained that she and her colleagues grouped their questions under three broad research categories: the “system,” the classroom, and students.

The following questions are related to the “system”:

-

What are the effects of limited resources on the support of education reform?

-

The Framework (Figure 1-1) shows the system that could be influenced by the NSES. It’s a dynamic system, and certain activities or components of the system may have more effect than others. What leverage points, or drivers, would likely lead to the largest effects?

-

What assessments best enhance individual student learning and how can we use these assessments to drive the system?

-

How would we recognize advances in student learning if we were to see them?

-

What would be the effects of reducing the number of content standards (i.e., to a more teachable number)?

-

What can be accomplished through informal education to increase public awareness of science and science education as envisioned

-

by the NSES and increase public awareness of the efforts to improve it? How can we utilize citizens’ influence on education to support reform efforts?

-

What kinds of assistance from outside the education system would be most helpful in promoting standards-based reform?

The following questions are related to the classroom:

-

How can we learn more about what actually goes on in science classrooms?

-

What are the cultural barriers for teachers in understanding the NSES, and what is the ability of school systems to institute the NSES in light of those barriers?

-

What kind of professional development will enable teachers to implement standards-based materials, and what are the student-learning outcomes that result from that?

-

Do we have any examples of where the NSES have changed pre-service education? How was that change accomplished? What has happened as a result?

The following questions are related to students:

-

What assessments best enhance individual student learning, and how can we use those assessments to drive the system?

-

Are different teaching approaches necessary to effectively reach student groups with different backgrounds?

QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS

After the panelists finished making their presentations, Sneider solicited questions and comments from the workshop participants.

Martin Apple, of the Council of Scientific Society Presidents, pointed out that nearly every presenter touched on the need for more information regarding the NSES and pre-service teacher education.

Wheeler noted that his group was surprised and concerned about the “lack of evidence” that pre-service education had been affected by the NSES.

Apple wondered why, given the consensus that was built into the NSES, there wasn’t a better plan for the implementation of the NSES, “other than hope and diffusion.” He asked, “Is there something we should do now to create a more active process?”

Clay-Chambers expressed the need for more “clarity” with respect to what is really meant about implementation of the NSES. In order to move forward, she said that more questions should be answered, “particularly with respect to the reform agenda.”

Diane Jones said, “We had a discussion in our group about the fact that there was a lot of investment in developing the NSES, marketing the NSES, and developing commercial curricula that promote the NSES before there was a lot of thought or money given to how we are going to assess their impact. So, it was a little bit of the cart before the horse.” It would have made sense, she added, to agree upon assessment tools right from the start to track the impact of the NSES on student achievement.

Jerry Valadez, of the Fresno Unified School

District, wondered why there were so few questions raised about equity issues related to the NSES.

Several equity issues were in fact raised by Group A, Wheeler said, but they were not included in the ones reported out to the workshop participants. Century noted that Group D “had a very extensive conversation about that.” She reiterated her previous point, about the need for more research on the relationship between standards-based reform and student outcomes among different student populations. “We also talked about how curriculum developers can create materials appropriate for subpopulations,” she said, “or that could be adapted for subpopulations, given the bottom line of publishers and [their] wanting to reach the largest market.”

Cartier said that Group F had talked about equity and how it relates to the overall issue of school cultures, which mediate a teacher’s ability to operationalize standards. Those cultures, she added, might be affected in part by issues related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors. Her group also questioned whether there were good data about the importance of using different teaching approaches to reach different student populations most effectively.

Drayton noted that Group E had some concerns about how language-minority students were being assessed on their understanding of science. He also said that one member of his group, a publisher, pointed out that just because book publishers make certain materials available—Spanish language curriculum materials, for example—doesn’t necessarily mean there is a large market for such materials.

Iris Weiss emphasized a previously made point, about the need to broaden the research to include schools and districts that aren’t engaged in school reform, and not just those that are. “If we are going to improve science education generally,” she said, “we need to know how to change the places that aren’t trying to reform.”

SUMMARY: FROM VISION TO BLUEPRINT

For the day’s final formal presentation, Brian Stecher offered an overview of the workshop participants’ responses to the research papers. In doing so, he explained that the NSES as they currently exist are “a vision about what might be done,” but what most people—including the workshop attendees—are looking for is “a blueprint.”

The difference, Stecher said, is that a vision is “kind of an emotional document that gets you marching in a common direction and gives you some vague view of the outlines of something.” A blueprint, on the other hand, is “very specific” and contains “drawings from which you can actually build something.”

The vision contained in the NSES, he added, is somewhat vague. The NSES may have some internal inconsistency or conflicting points of view. They may not be perfectly aligned with other documents, such as the AAAS Benchmarks or NSF documents. As a blueprint, however, “that wouldn’t be tolerable.” So the goal is to “clarify the fuzziness” into something that is implementable. “It has got to be contractor-ready,” he said. “That is what … the teachers in the trenches would like to have, and that is what some of the discussion today has been about.”

A blueprint, Stecher continued, isn’t just a set of instructions for how to build something. It must

also contain evidence of the quality of the design. But that element is missing from the NSES. “We didn’t build the part of this that will let us say whether or not it works,” he said. “We don’t have the assessment to say what is going to happen—whether, in the end, students will have learned science in a way that we vaguely hope they will.”

It is clear then, that more research is needed in order to turn the vision contained in the NSES into a blueprint for action. “We need a more comprehensive vision of research to provide answers,” he said, “so that three or four or five years down the road, there won’t be all the gaps. There will be some information to fill those gaps.” We need to “map out the terrain of unanswered questions and be systematic about making resources available to address them.”

Stecher called for more research that looks at student learning and the act of teaching. He called for more research that is sensitive to school and classroom culture that tries to determine how well teachers understand the standards, how they translate them into practice, and how they communicate them to students.

“It is clear,” he said, “we need research on assessment development to produce measures that tell us whether or not students are more inquisitive, have scientific habits of thought, can reason from evidence, and master the kind of principles of science that are really inherent in the NSES.”

Stecher also stressed the need for more research that focuses on pre-service and in-service teacher education. “If we implement [the NSES] through intensive pre-service training, if we put more money into pre-service training and less into in-service training, does it lead to better effects than if we do it the other way?” he asked. “To find the answers to those questions, you really need to mount some experiments on a small scale and study them and see whether they work or not.”

He called for more research on how to take micro-level results and apply them to the macro-level. “So, once we understand something about what goes on in the classroom,” he said, “how do we make those things happen on a larger scale?”

The work accomplished so far, he concluded, provides “a really good basis for moving forward and for making the most out of a number of years of really thoughtful work on bringing this vision to fruition. If we do this again in five years, maybe we can all be patting ourselves on the back about how well it has all happened. I would hope so.” Sneider thanked Stecher for his summary and then added his own closing remarks. He thanked the participants for their hard work, adding, “You carry with you the success or failure of this workshop, and I hope that you have found the time valuable, that all the colleagues to whom you will be reporting also find it interesting.”