9

Diversity in the Industrial R&D Workforce: Challenges and Strategies

D. Ronald Webb

Procter & Gamble

It is a pleasure for me to be here today and speak to the topic of “Diversity Models that Work.” I want to thank the workshop organizers, and in particular Dr. Isiah Warner, for inviting me. This invitation came, in large part, based upon Dr. Warner’s understanding of Procter & Gamble’s (P&G’s) past success with, and future commitment to, diversity. When first invited, I was not entirely sure how our experiences would complement those from the academic and government sectors. But after listening to the speakers yesterday who represented academe and government, I am now confident that our perspective should be quite helpful.

As manager of doctoral recruiting at P&G, I have the responsibility to attract advanced-degreed candidates to apply for R&D positions with our company. P&G has a commitment to building a diverse workforce, and thus I also own the particular responsibility of ensuring that our applicants represent minority, as well as majority, scientists. This has allowed me to develop an information-based perspective on how successful P&G has been in meeting diversity goals, and I will share these results with you today.

But before I do, I want to roll the clock back to 1971 when I first joined the company. I think that it will come as no surprise that our R&D workforce at that time was a monoculture, comprised largely of white males. Particularly in regards to Ph.D. employees, I saw very few women or people of color. Unfortunately, we heard from the speakers yesterday that this is still an accurate cultural description for departments of chemistry in most of the academic institutions in our country. What is my point? It is that academe should take comfort in the fact that we had the same problem, namely lack of diversity, but we proactively and successfully addressed it. In other words, there are solutions, and I believe they can be successfully modeled. We have made great strides, as I will demonstrate, and we are quite proud of our accomplishments. Can we do more? Absolutely, and we will do more by recognizing that our work here is not done, but needs constant focus and attention.

WHAT IS DIVERSITY?

First and foremost, diversity is valuing our uniqueness. It has already been pointed out in this workshop that diversity is not just defined in terms of race or ethnicity, but also should be extended to reflect other measures of difference, including sex, age, nationality, cultural heritage, sexual orientation, etc. As I prepared for this presentation, it was unclear to me what the workshop organizers had in mind as they used the term “diversity” in setting today’s agenda. I cannot possibly address all measures of diversity, due to time constraints, but instead chose to focus on a few of the more common topics, namely, race and sex. However, I want to assure the audience that we at P&G view diversity in its broadest sense and work very hard to value all of its components.

Diversity is also a matter of ethics. It is “doing the right thing.” A diverse workforce is proof positive that the organization respects the individual, providing equal opportunity to all for personal growth and development. A diverse workforce is also an outward indication that all individuals in the organization value diversity. If this were not the case, if diversity was only important to top management, then their majority peers would not make minorities welcome, and lack of retention would be an expected outcome. Respecting diversity yields cultural inclusion, and inclusion provides a positive environment for minorities to feel welcome.

Last, but of equal importance, diversity is a fundamental business strategy for success. Why? P&G markets consumer products globally, and thus we have to understand the needs of very diverse customers. A monoculture of white males cannot have all the answers to all questions. However, by building a diverse workforce, we will better understand such consumer needs, understand them more quickly than our competition, and thereby build and maintain a critically important competitive edge.

DIVERSITY AT P&G: A CORPORATE PERSPECTIVE

Valuing diversity is today an essential component of building a world-class, global organization at P&G. I recognize that this may sound like a company line, but let me expand on this theme. P&G has a set of core values, with “people” lying at the heart of this core. Thus, other values, such as leadership, trust, integrity, etc., must be seen as secondary. Valuing people first is clearly a natural springboard to valuing diversity

With this as a backdrop, when people are your most important asset, I submit that it is much easier to bring about a cultural change and develop a more diverse workforce when such a workforce may not currently exist. This also fits well with other cultural goals, such as “hiring the test” and “promote from within.” By attracting the best applicants, regardless of majority or minority status, and giving them equal access to higher level positions, we build upon any hiring successes we may have and turn them into retention successes. I will come back to retention issues shortly.

I now want to build on a theme highlighted by previous speakers, namely that commitment to diversity must begin at the top. This was essential to the diversity success seen most recently at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (Dr. Freeman Hrabowski), and at Louisiana State University (LSU) (Dr. Isiah Warner). The message is clear. You have to have someone at the top truly believe that building diversity is the right thing to do, and then see to it that it happens. Leaders must marshal the forces to make change and be consistent in their demand for change to take place. It cannot be an “on again, off again” program, but one of sustained advocacy. In other words, if there is no incentive to change, then change is unlikely to happen.

We are fortunate at P&G, in that building diversity has been the commitment of our top corporate officers for decades. Today, our president and CEO, Mr. A. G. Lafley, recently summed this up by

stating that, “I am putting particular importance on increasing the representation of women and minorities in leadership positions at all levels of the Company.” With such unambiguous expectations, it is no surprise that we now have a Corporate Diversity Leadership Council to track diversity progress and hold management responsible for meeting diversity goals and expectations.

I would like to conclude this portion of my talk by highlighting a different aspect of corporate commitment to diversity. Remember that one of my tasks is to attract minority doctoral candidates to seek research and development (R&D) careers with P&G. I submit that my task is incrementally easier if P&G is also sending other, non-R&D-related, positive signals to the minority workforce, demonstrating that ours is an attractive and welcoming culture for such workers. This is what we have done for the majority workers for decades, and it needs to be done for all employees.

P&G has a rich history of embracing diversity. For example, there are a number of industry initiatives that demonstrate, in a very public way, such a message. Perhaps the best example is in our supplier diversity programs. This effort has been in place for more than 30 years and has led to minority suppliers to P&G growing from only 5 to 6 suppliers at that time, to over 1,000 today. As a result, total Company expenditure to minority suppliers exceeded $500 million in 2000.

Similar examples can be cited in the area of charitable giving. The philanthropic P&G Fund contributed about $4.5 million in 2000 to a wide variety of minority-related causes. This included funding for education-focused initiatives, such as the United Negro College Fund, the Hispanic Scholarship Program, just to name two, as well as financial support for other nonprofit organizations such as the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center and the Minority Women’s Health Initiative.

Refocusing on R&D, P&G participates in, and/or financially supports, a wide variety of professional societies and organizations. For example, our scientists, minority as well as majority, are active members of such organizations as the Society of Women Engineers, the Society for Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science and the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers (NOBCChE). Dr. Leonard Small, a P&G researcher, is a recent past president of NOBCChE. Such efforts provide us with the opportunity not only to show corporate support, but also to allow our employees the possibility to be a mentor, to network, and to make a difference at the personal level in regard to attracting minority scientists to industrial research careers.

Last, diversity efforts, such as those previously discussed, have resulted in numerous diversity-related awards. It is not possible at this time to identify them all, but some of our more noteworthy examples of public signs of recognition in this area include the Opportunity 2000 Award, presented by the Secretary of Labor in recognition of P&G workforce strategies to ensure equal employment opportunities; the 2000 Corporate Circle Award from the National Medical Association for facilitating the development and use of state-of-the-art biomedical knowledge for improved therapeutics in African American patients; and The 100 Best Companies for Working Mothers, as published in Working Mother Magazine (2001). In regard to the latter award, it should be noted that P&G was in the top ten of these 100 companies.

THE R&D ISSUE: UNDERREPRESENTATION OF MINORITIES IN SCIENCE

P&G averages hiring about 60 Ph.D. scientists each year. Approximately a third are chemists; another third are life scientists; and the latter third are a broad mix of specialties including medicine, statistics, pharmacy, engineering, etc. Thus, this represents P&G’s “demand” for advanced-degree candidates. The academic “supply” of such candidates should also be considered. Because the theme of

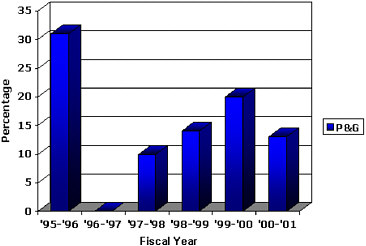

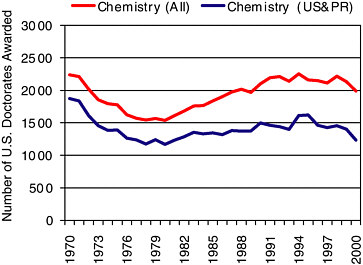

FIGURE 9.1 Doctorate degrees in chemistry awarded in the United States, 1970 to 2000.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, Science and Engineering Doctorates: 1960-88, NSF 89-320, NSF, Washington, DC; and National Science Foundation, Doctorate Recipients from United States Universities: Summary Reports (Individual), 1989 through 2000.

the workshop is “Minorities in the Chemical Workforce,” let us concentrate on the U.S. supply of doctorate degrees in chemistry.

Figure 9.1 shows the number of doctorate degrees in chemistry awarded in this country over the past 30 years. The top line in this graph represents the total number of degrees granted annually in the United States, while the bottom line represents the number awarded to only U.S. citizens or permanent residents. I would like to make two points with this figure. First, the total supply has been relatively flat over this time period, roughly averaging about 2,000 doctorate degrees awarded per year. Last, the gap between the top versus the bottom line is a direct measure of the number of doctorate degrees in chemistry that is awarded each year to foreign national students, and this gap has been widening over the past few decades.

A theme we will continue to hear in this workshop is that minorities are underrepresented in the sciences, and chemistry is no exception. I will share the numbers shortly. If the goal is to increase representation of minorities among candidates receiving doctorate degrees in chemistry, then the only successful strategy to reach this goal is to accept more minority students in these graduate programs than have been accepted in the past. However, with a fixed supply of doctorate degrees, this can be achieved only at the expense of others who, in the past, have had relatively greater access to such degrees. We heard yesterday from Dr. Steven Watkins (LSU) that they are changing their historical demographics of their graduate student population by accepting fewer foreign national students and accepting more minority students who are U.S. citizens or permanent residents. This is certainly one approach, but there

are others. My key point is that chemistry departments in the United States must make such tough choices if we are going to narrow the national minority underrepresentation gap in science.

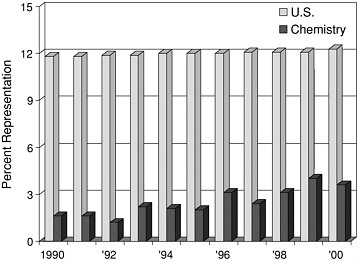

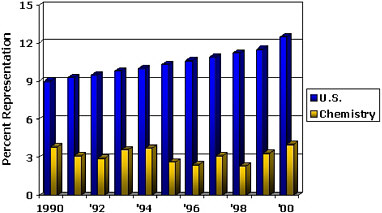

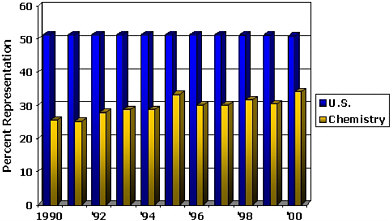

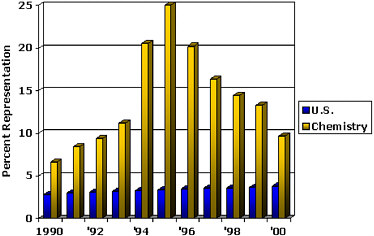

Figures 9.2-9.5 compare and contrast the annual percent representation of different ethnic groups in the U.S. population versus those receiving doctorate degrees in chemistry. For blacks, Hispanics, and women (Figures 9.2-9.4, respectively), it is clear that the percentage of doctorate degrees awarded to each group over the past decade was significantly less than their national representation. In other words, relative to national demographics, these groups are underrepresented minorities in science. In contrast, Figure 9.5 demonstrates that Asians are not an underrepresented group because they receive far more advanced degrees in chemistry than would be expected based upon their national demographic profile. Because this data set is for U.S. citizens or permanent residents only, the significant lack of underrepresentation in science for Asians could be highlighted even more dramatically if I were to also account for those advanced degrees in chemistry awarded to foreign national students who are of Asian descent.

A more compelling case for underrepresentation can be made by considering the number, not the percentage, of advance chemistry degrees awarded each year to minorities. For 2000, blacks received only 44 of the 1,990 doctorate degrees in chemistry awarded by all degree-granting institutions in the United States [1,236 of these degrees (62 percent) were awarded to U.S citizens or permanent residents]. Similarly, Hispanics and women received 50 and 422 doctorate chemistry degrees, respectively,

FIGURE 9.2 Representation of blacks in the United States vs. doctorate programs in chemistry, 1990 to 2000.

SOURCE: NSF/NIH/NEH/USED/USDA/NASA, Survey of Earned Doctorates, Doctorates Awarded to U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Fine Field: 1990-2000, Table 3, National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2000; and Population Estimates Program, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, December, 2000.

FIGURE 9.3 Representation of Hispanics in the United States vs. doctorate programs in chemistry, 1990 to 2000.

SOURCE: NSF/NIH/NEH/USED/USDA/NASA, Survey of Earned Doctorates, Doctorates Awarded to U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Fine Field: 1990-2000, Table 3, National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2000; and Population Estimates Program, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, December, 2000.

FIGURE 9.4 Representation of women in the United States vs. doctorate programs in chemistry, 1990 to 2000.

SOURCE: NSF/NIH/NEH/USED/USDA/NASA, Survey of Earned Doctorates, Doctorates Awarded to U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Fine Field: 1990-2000, Table 3, National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2000; and Population Estimates Program, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, December, 2000.

FIGURE 9.5 Representation of Asians in the United States vs. doctorate programs in chemistry, 1990 to 2000.

SOURCE: NSF/NIH/NEH/USED/USDA/NASA, Survey of Earned Doctorates, Doctorates Awarded to U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Fine Field: 1990-2000, Table 3, National Opinion Research Center, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, 2000; and Population Estimates Program, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC.

in the same time period. These numbers are especially noteworthy when one recognizes that the U.S. population demographics for each of these groups are measured in the tens of millions.

ATTRACTING STUDENTS TO SCIENCE

As highlighted earlier in my talk, P&G is committed to building a diverse workforce, and our R&D community is no exception. However, our ability to attract and hire the best minority scientists is directly impacted by the fact that the number of minority candidates with advanced science degrees is woefully small. P&G cannot immediately or directly fill this academic “pipeline,” but we can help by providing a demand for such candidates, and thus indirectly attract more minority students to pursue science careers. Because all aspects of our education system are potential “feeders” into this pipeline, we take the opportunity to interact with all phases of education and, in the end, hopefully make a positive difference.

The first place to start is in K-12 education. Our efforts here are primarily regional and are best exemplified by our Saturday Science program. Each spring, we invite between 60 and 100, predominantly African American, 5th graders to visit one of our research facilities and participate in this event. The students are drawn from a number of our inner-city schools and are selected in partnership with the local chapter of Minorities in Mathematics, Science & Engineering. Our objectives are to excite the students about science, give them a sense of scientific career opportunities, and also give them a chance

to interact with potential mentors and role models. The day begins with a science magic show, which does a wonderful job of setting a positive and up-beat environment, and then moves on to various interactive modules that focus on chemistry, nutrition, or math. Saturday Science is always well received and highly rated by the students and their teachers.

Additional efforts in the K-12 area include P&G’s financial support for the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards and my personal participation in the Ohio Mathematics and Science Coalition. The latter is an independent organization committed to continuous, systemic, and sustainable improvement in pre-K-16 mathematics and science education for Ohio’s nearly 2 million students.

At the undergraduate education level, one of our more longstanding efforts has been to attract these students to pursue an advanced degree. Giving such students the opportunity to conduct independent research projects is one effective strategy because it allows them the chance to have the challenging and rewarding experience of conducting original research. P&G has summer internship opportunities for undergraduates each year, and this has been a very popular and successful program for us. We also collaborate with local universities who independently developed the same approach. The most notable of these is the big ten’s Summer Research Opportunities Program, organized and coordinated by their Committee on Institutional Cooperation. Hundreds of students across the country are invited each year to conduct independent research projects on any of their campuses, and hopefully attract them to choose the big ten conference if they decide to pursue an advanced degree. My office provides financial support for this program, and our employees also participate in their annual celebration event by providing mentoring and role model opportunities to the students.

There are other efforts, too numerous to mention, that P&G relies on to attract undergraduate minority students to science careers. But before I move on, I wish to highlight one that we are very proud of, namely, P&G’s financial support of the American Chemical Society (ACS) Scholars Program. ACS conceived this program in 1995 as an effective way to provide scholarships for minority students interested in a chemistry career. It has been very successful, providing more than 600 minority students the opportunity to go to college and obtain an undergraduate degree. Their retention and graduation rate is outstanding, as is the fact that the GPA of their scholars is admirably high.

Turning my attention to graduate students, which is my area of focus, P&G has a number of successful efforts in place to attract minority students to industrial careers. P&G is one of the few companies to offer, to both minority and majority doctoral students alike, summer internship opportunities where they can conduct independent and original research in an industrial setting. We also offer industrial postdoctoral positions to any newly minted Ph.D., in essence mirroring the typically academic model of providing additional two-year research experiences to such candidates. The difference, of course, is that P&G postdocs gain an industrial research experience, which gives them a better understanding of what our employment sector has to offer in terms of professional growth and development. I can add that a large fraction of our postdocs will choose to apply for full-time positions after their postdoctoral contract has expired, and we are happy to make them job offers.

Our most successful, and original, strategy for attracting minority graduate students to industrial careers is our Research and Technical Careers in Industry (RTCI) conference. This is a three-day event, now in its 12th year, which is held each June in Cincinnati. Participants must be doctoral students in chemistry, biology, or engineering and in their final year of degree attainment, or currently finishing a postdoctoral assignment. In addition, the conference is offered to U.S. citizens or permanent residents who are also African American, Hispanic, or Native American. About 24 participants are chosen each year from an applicant pool that averages about 60.

The primary objective of RTCI is to provide a focused, fact-based insight into industrial research career opportunities and thus help conference participants choose between typical career paths such as

industry, academia, or government. Which path they choose is not the issue. With the facts made available, we believe the conference participants are better able to make well-informed career decisions.

What is RTCI all about? It is a conference intended to provide participants the chance to learn more about how industrial research is conducted and managed, network with minority scientists and scientific managers and learn about key factors for success, appreciate the value of team research and its role in bringing about innovation and technology development, evaluate their interview and resume-writing skills, and understand the value of diversity in a corporate culture. The conference is highly rated each year by participants and self-described as one of the more informative conferences many have attended. To learn more about this conference, please go to our website (www.pg.com/rtci) where more detailed information is available.

RECRUIT, REWARD, RECOGNIZE, AND RETAIN

I would now like to move from discussing generalities of diversity models that work to considering some specific measures of success. The theme of the remaining portion of my talk is recruit, reward, recognize, and retain. These are important concepts in building a diverse workforce, because if you omit any one of them you will substantially decrease your likelihood of success. In other words, it is not enough to just recruit. If you cannot retain minority candidates in your workforce, then the recruiting cycle is nothing more than a revolving door and it yields no net gain. And as I will discuss, rewarding and recognizing your employees, essentially giving them a comfortable and inclusive environment to work in, are the best ways to ensure retention.

Recruit: The recruiting strategy I rely on to attract minority, as well as majority, candidates is fairly standard and easily duplicated by anyone. In addition to the RTCI conference noted above, we continue to rely heavily on campus recruiting. Representatives of my office visit about 40 campuses each year and annually conduct about 600 campus interviews with doctoral chemistry students who are no more than a year away from graduation, or who are completing a postdoctoral assignment.

Although some employers are not relying on this approach as much as they did in the past, I continue to see this as a key recruitment strategy. In any given year, about half of the chemists we hire come from our campus recruiting efforts. Other, and again traditional, strategies for finding candidates is advertising (print and Internet job posting), national meetings of professional societies (e.g., the National Employment Clearing House of the ACS), regional or campus job fairs, referrals, and occasionally search firms.

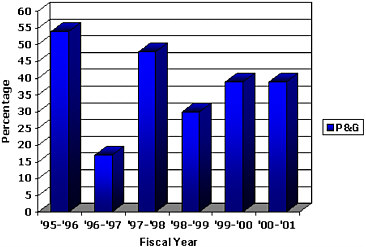

How are we doing? I conducted a doctoral recruiting benchmark study in 2001 with some of our industrial competitors, and I am pleased to report that we are doing very well. Representatives from Dupont, Dow, 3M, Eli Lilly, Union Carbide, Bayer, and Kodak provided doctoral hiring statistics over the preceding six consecutive fiscal years, which allowed me to compare and contrast such data with ours. Specifically, I evaluated the percentage of new Ph.D.s hired by each company who were black, Hispanic, or female. The data for the two ethnic groups were summed for analysis and presentation, while the hiring statistics for females were analyzed and reported separately. It should be pointed out that there were some nonrespondents, on any of these measures, for any fiscal year. The results are presented in Figures 9.6 and 9.7.

The results in Figure 9.6 show that, with the exception of fiscal 1996-1997, at least 10 percent of the doctoral candidates hired by P&G were either black or Hispanic, with an average annual underrepresented minority hiring rate of 15 percent over the six years measured. To put these numbers into perspective, we need to consider both the academic supply of advanced-degreed minorities as well as the average hiring rate of our industrial competitors.

Figures 9.2 and 9.3 show that blacks and Hispanics each received about 3 percent of the doctorate degrees in chemistry that were awarded to U.S. citizens or permanent residents over the period of the industrial benchmarking survey (1995-2000), for a combined minority group representation value of 6 percent. Similar values (not reported) exist if one looks at the percent of doctoral degrees awarded to minorities in other fields, including life science and engineering. Thus, the results in Figures 9.2 and 9.3 provide a representative example of the broader issue of underrepresentation in science. It is thus clear that P&G’s average annual hiring rate of advanced-degreed blacks and Hispanics (15 percent) is at least two times the academic supply value (6 percent) for this group. This is a conservative estimate, with our hiring rate increasing to about three times the academic supply value if doctorate degrees awarded to foreign national students are included in the analysis.

The benchmark study also indicated that P&G’s minority hiring rate exceeds that of our corporate competitors. Over the six years evaluated, the pooled results of the seven industrial partners who participated in this study show that their underrepresented minority hiring rate averaged 7 percent over the six-year period, with a standard deviation of 6 percent (n = 28 data points). P&G is clearly leading the way in building a diverse R&D workforce, and I take great pride in this.

Our results for hiring advanced-degreed women are just as successful. Figure 9.7 shows that P&G’s annual hiring rate for women with doctorate degrees ranged from 17 percent to 54 percent over a six-year period, yielding an average annual hiring rate of 38 percent. This average hiring rate exceeds academic supply by a considerable margin (Figure 9.4). P&G’s average hiring rate for advanced-degreed women is also greater than that of our competitors, where advanced-degreed women represented about 25 percent of their incoming workforce (standard deviation = 10 percent, n = 31 data points).

It would be appropriate at this time to recognize the success P&G has had in attracting women and minorities to our workforce by looking beyond the R&D sector and focusing on management hiring results. I gathered data for the past two consecutive fiscal years, and I am pleased to report that for fiscal 2000-2001, 35 percent of managers hired were black, Hispanic, or Asian. Note that Asians are included here as a minority group due to their low representation in the U.S. demographics (see Figure 9.4). A similar value (37 percent) was achieved for the last fiscal year reporting period (2001-2002). For perspective, the appropriate comparative value in this case is about 28 percent (sum of U.S. demographics for all three groups, see Figures 9.2-9.4). And while females represent about 50 percent of the U.S. demographics, P&G’s management hiring rate for females over the past two fiscal years was 52 percent and 48 percent, respectively. Both measures show quite convincingly that P&G is closing the minority underrepresentation gap, and validating the national diversity awards I spoke about earlier, which have been bestowed upon P&G in the recent past.

Reward and Recognize: There are three key components of a successful reward and recognition program, with ultimate success being measured in terms of retention, and each one is as equally important as any other. These components are (1) performance-based rewards and recognition must be made available to everyone, both for majority and minority employees; (2) public acknowledgment of success (e.g., awards, titles of advancement) is essential in achieving long-term employee satisfaction and professional development; and (3) all employees must proactively bring inclusion of others into all facets of the business.

This latter point, mentioned earlier in my presentation, is crucial. A leader can articulate the vision and set the tone, but the rank and file employees are the ones who bring about cultural change. I recognize that due to our “paramilitary” culture in industry, as compared with academe, it is relatively easier for the industrial rank and file to follow the lead of a leader. However, this is not an excuse for academia to use for justifying their lack of diversity today, but it does indicate that they likely will have

to develop their own strategies for recruiting their rank and file, and ultimately bring about their own cultural change.

P&G’s reward and recognition system is best exemplified by our dual-ladder system for promotion. Employees in R&D will choose, early in their career, whether to advance as a technical expert or as a manager of science. Both are equally valued, and this is important, so there is no stigma associated with one choice or the other. The management path for promotion is traditional and basically resembles all other industrial corporations, as well as the tenure track promotion system in academia. But the key here is that such a promotion system is public, not personal and private. It goes beyond a handshake and a raise and awards titles to individuals selected for advancement. Our titles include such terms as section head, associate director, director, company officers, etc. Others may use different titles, but the title used is far less important than its symbol, namely, the outward recognition of personal success.

We modeled this approach in our technical ladder for advancement with titles such as senior scientist, principle scientist, research fellow, etc. Not every industrial employer offers such a dual-ladder system, but I submit it is invaluable in terms of employee retention. This is because if employees have satisfactory choices for promotion, versus the one-size-fits-all approach of a single management system for advancement, then you will have satisfied employees who tend to stay with their employer over the long term.

How are we doing in terms of reward and recognition? Based upon the most recent results I found available (October 2001), 5 percent and 10 percent of our company officers today are female or non-Caucasian, respectively. Importantly, these values are as high as 22 percent among such groups poised for promotion to company officer status. I conclude that we have come a long way from those days 30 years ago when there were neither women nor people of color at such levels in our organization. We are by no means done here, but I submit we have made great progress in the recent past.

Retention: One of the more effective strategies for ensuring retention of minority groups, beyond an effective reward and recognition plan as discussed above, is to proactively provide, and also value, mentoring and support groups. I cannot overemphasize how important this can be. I informally polled a number of blacks, Hispanics, and women in our R&D community, and asked them to share their views on this subject. I heard loud and clear that mentoring and support make them feel more welcome and secure in a majority population. This is no surprise if you realize that mentoring and support, for majority-to-majority individuals, has been in place since the company was founded 165 years ago. It is how we help others to grow and develop. But in this case, we are saying that majority-to-minority mentoring and support may not exist, or may not be as effective as it needs to be for minority populations.

The poll confirmed this, and in their words indicated that mentoring and support by and for minority groups provide a safe, family-like environment to discuss and understand important business issues. Specifically, this includes the opportunity to discuss and understand such topics as successful on-board technique, company politics and business strategies, personal and/or technical resources, models of success and histories of failure, unwritten rules and expectations, obtaining constructive criticism and feedback on performance, and how to develop leadership skills.

Based on this perspective, it should come as no surprise that there are a number of minority mentoring and support groups at P&G, and these are actively supported by majority peers as well as our company leaders. I mentioned RTCI previously, the summer conference designed to highlight industrial research careers for minority scientists. We have hired a number of individuals through this conference, and they use this experience to remain close. They get together to shape the future of RTCI and to participate in the conference in a very active way. In turn, they interact with each other and get something out of it at the personal level. Other more formal P&G support groups include the Black

Technical Ph.D. Group; Black Women’s Development Network; Latino Ph.D. Group; and Women Directors and Above in R&D, just to name a few.

If we now look at retention results, as a measure of how we are doing, I can again state that we are doing very well. Based on average turnover data from 1997 to 2000, from all business sectors, the annual turnover rate at P&G was about 6 percent. The turnover for females was slightly less (4.5 percent), whereas the turnover for minorities (black, Hispanic, or Asian) was a little higher (7 percent). I do not have any benchmark data to quote, but anecdotally can share that double-digit turnover rates are not uncommon in business. More importantly, we do not see dramatic turnover rate differences when we look at women or minorities as employee subgroups.

So in conclusion, building a diverse workforce is not easy, but it can be done. Speakers at this workshop have shared examples of success for others to model, and they have some very common themes worth noting. First, to make a cultural change you need an active and unwavering leader or advocate of change. Such an individual will be responsible for defining success, insisting on results, and importantly, holding others accountable for change. You also need the rank and file to embrace the challenge of change. The leader cannot do it alone. Peers of newly hired minority coworkers must be willing to accept them, include them in their working groups, and thus make minorities feel welcome. If this does not happen, you will not be able to retain new hires, and the hiring process essentially makes no net gain in regards to building diversity. And finally, recruiting is a challenge, but as an end result it is not enough. An effective and healthy diverse workforce will be one that offers performance-based rewards and recognition to majority and minority employees alike, which in turn reduces turnover of minority groups.

DISCUSSION

Tyrone D. Mitchell, National Science Foundation: I want to congratulate you on doing a lot of the things right on diversity at your company.

Some of the data I would like to see that you did not show are on retention. Do you track the number of unrepresented groups and women in the “years of service” category? Those data are going to show how well you are doing. For example, in a lot of corporations the “5 to 15 years service” category is not populated with a lot of underrepresented groups, because people tend to wash out during that period of time for various reasons. So, do you have that kind of data available?

D. Ronald Webb: Your point is well taken. I have some of the information you asked for, but not all.

I recently looked at this issue, but only for women. On any given year, the percent of women who are leaving the company is, as I said in my talk, about 4.5 percent versus a 6 percent annual turnover rate for all R&D employees. This means males are leaving annually at about a 7.5 percent rate.

We also see a difference when we look at how long females stay in the company relative to males. We have been hiring women since the 1970s. It is now 2002, and in 2001, we saw the first women retire versus leaving at an early stage of their career. More specifically, most women hired into R&D opted to leave prior to a typical retirement age of about 25 years of service, with a 10- to 15-year departure time frame being frequently encountered. Exit interviews showed that they left for all the various reasons you can imagine, such as choosing to stay home and raise a family, help aging parents, or start another career.

Monica C. Regalbuto, Argonne National Laboratory: I have a question for you. You have a postdoc program, and I was wondering what percentage of those Ph.D.s that you hire come from that program.

D. Ronald Webb: I am not sure I understand the question. P&G hires postdocs in two different ways. First, we hire individuals at an entry-level position who are completing an academic postdoctoral position at a college or university. Second, we offer freshly minted doctoral students the opportunity to get postdoctoral training with us rather than with a university. Which of these two postdoctoral individuals are you talking about?

Monica Regalbuto: The latter, the ones that postdoc with you and are then eligible for employment. The reason why I brought this up is, we also have a postdoc program. The younger staff have been resentful and it is what they call slave cheap labor—a mechanism that is being used by many companies, universities, the national labs, and all across the spectrum to keep these employees for two or three years at a much lower-ranked level and pay.

D. Ronald Webb: I should first point out that our industrial postdoctoral program is quite modest. We average bringing in about three to five individuals a year, relative to an average doctoral hiring rate of about 60 per year. I should also point out that we do it for positive reasons, not to use them as a cheap labor force. We want to give them the additional postgraduate “seasoning” they seek, but in this case in an industrial rather than an academic environment. Our annual salaries are also quite competitive, currently averaging in the mid-$50s versus the more typical academic pay scale of mid-$30s.

The vast majority of those who participate in our postdoctoral program are eager to apply for full-time employment with us once they have fulfilled their contractual obligations, and we certainly consider them if their skills meet current hiring needs.

Thus, to answer your question, I would estimate that we average hiring about two to three of our postdocs in any given year, which means that, relative to an average hiring rate of 60 per year, these individuals make up less than 5 percent of our new hires.

James W. Mitchell, Lucent Technologies: P&G is to be commended for the progress that you have made with respect to diversity. If you analyze what you have there, there are some key elements that have to be present in an institution if you are really going to make progress.

We have some of the same key elements, and I just wanted to mention a couple of them. You certainly have the top-level management, who speaks, and I am sure you also have widely dispersed written information about what the policy was with respect to representation within the institution.

D. Ronald Webb: Correct.

James W. Mitchell: That has to happen at the top. You also mentioned that people in the down line must also come aboard to make it happen.

D. Ronald Webb: Right again.

James W. Mitchell: But second, within institutions, in the R&D sector, for the majority of skeptics, there must be someone present—minorities and females—who have already provided existence proof that excellence of performance within them just like it occurs within anyone else. That is certainly necessary to get many of the people to embrace a program and go along with what the CEO says.

Then an institution must have specific programs that fit the corporate culture of that particular institution, and people within that institution have to figure out what are the specific programs that they must put into place.

You then have to have a process for identifying and attracting what I will call minorities and women who are immune against bias and racism. We talked about the perceptions that other people have, based on programs and so forth that are in place. You have to try on people who do not care about the perceptions of other individuals, people who are excellent in terms of their performance and their self-image, and who will come in and perform the scientific and research job that you have for them.

Finally, there are institutions who claim that they cannot find the caliber of individuals that they want to hire. Then you have to do something about generating them. Some 30 years ago, Bell Laboratories claimed that we could not find the number of minorities and women of the caliber that we would like to hire. So we did something to generate them. We now have a postdoctoral program that has a mentoring component and summer research prior to going to graduate school. Over 250 minority and women have finished that program, at a 71 percent completion rate. They have gone to the best schools in the country; 63 of them have academic jobs.

This is not confined to just chemistry alone, but it is all of the fields that we hire in. Those individuals are now in academia, providing a network that can replicate themselves. So when the question came, how can we find the number of people that we need to hire, we told the institution that we need to be in the business of helping to generate them.

Now, corporate America has a better opportunity to make progress than an academic institution, but some of the same ingredients are going to have to occur in an academic department.

D. Ronald Webb: I agree wholeheartedly.

James W. Mitchell: And on the entire campus, if progress is going to be made there as well.

D. Ronald Webb: Thank you.

Robert L. Lichter, The Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation: I did not come prepared to comment on what James Mitchell just said, but I did want to say something on this notion that “we cannot find them.” That is one of the worst excuses given by academic institutions for not making change. Academic institutions have no problem raiding other places, or calling their contacts for help and leads, for the “best” people they want—if they are white. But they seem to have a problem doing this for the “best” people that they want if they are not white. There is a disconnect there that I do not get.

I look around this room and I see people who, if I were in an academic department and I wanted to get rid of its monochromaticity, I would go after them like crazy. But somehow they just do not do that, and I do not get it.

Anyway, that is not only why I stood up. I want to commend P&G for being an early and consistent supporter of the ACS Scholars Program.

D. Ronald Webb: Thank you.

Robert L. Lichter: But I do want to make a correction. The program provides support during the academic year. It has a summer research component, which is not a required part of the program, but it is certainly an encouraged one. Corporate donors who support the program have been very good about hiring these undergraduates for summer research appointments. However, the program’s funds provide academic-year scholarships.

Now I have to make a pitch. The program continues to need more and more support. Many here are already contributors, but if there are others who have not already ponied up, please do so. It is a really

good program, one that will make a difference. I think Yvonne Curry mentioned this yesterday, but I will say it again, that 114 ACS Scholars have completed their bachelor’s degrees. About half of them are now in graduate school. The first Ph.D. who was an ACS scholar has graduated from MIT and is now doing postdoctoral work at Berkeley.

Here is another example. I recently reviewed proposals in the National Research Council/Ford Foundation predoctoral minority fellowship program. Several applicants were ACS Scholars. So that program will make a difference in changing the numbers.

The other suggestion I want to make is that there is another venue for communicating to the broader community the notion that people who do science are not restricted to the ones that look like you and me. I am specifically speaking of museums. Every major metropolitan area has significant science museums, and smaller areas have them as well. Museum growth is spectacular in this country.

I do not know a lot about most other museums, but I do know a quite a bit about the New York Hall of Science. It has a program for training high school students to be “explainers” about the exhibits to museum visitors. These students come from the New York City school system and are about as diverse a population as you can get. So here is an opportunity both to train and to present to a broader public a broad, diverse array of youngsters who can and do, by that mechanism, become interested in science and who also serve as exemplars for others to become interested in science. That is something P&G might want to look into.

D. Ronald Webb: That is a good idea. Thank you very much.

Myra Gordon, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: I, too, would like to applaud P&G for what it is doing. I work in faculty recruitment and your presentation has given me better insight into the kinds of things you are doing that make you, in many cases, more successful in recruiting some Ph.D.s than we are.

From the programmatic initiatives you have described, I can certainly understand why many Ph.D.s would choose industry over academia. You pay them more, whereas higher education seems to be struggling everywhere. Industry does not have the promotion and tenure pressures. Women who want families and who want to do good science seem to be able to find a more hospitable environment with you. I see that you are clearly mentoring and nurturing people. You are providing not just technical things that people need to know, but it sounds as though you are also providing networks and places where people can feel connected, cared about, and important.

D. Ronald Webb: That is really critical. If you do not provide it, they are not going to be happy and they will not stay.

Myra Gordon: The question that I have for you is related to an elitism I see in some of the attitudes that some faculty have about the research done in corporate environments. How much of your research is published? For faculty members in the top-tier research institutions to feel as if the research that is being done in other settings is really good, it must be peer reviewed and published.

D. Ronald Webb: P&G encourages our people to publish their research, in all of the most appropriate journals, and also to present their findings at national meetings, network with peers, etc. This is how we communicate to the world that we are doing good science. The only time it tends to be different is that a larger percentage of our work, versus academic research, may eventually lead to a patent. At the time

the proprietary nature of the work is recognized, you have to maintain some secrecy so that it does not become prior art and you lose your patent protection rights. This is not different in kind, but in scale. I would also add that another way we let the world know about the quality of our science is by having patents granted. Obviously, patents signify original research, and we want to take credit for this. We currently have about 27,000 active patents and average filing 8 new ones each year.

If I may, I want to go back to your point that our environment looks better than yours. I will challenge you as I have challenged others personally. Our world is not perfect. I can compare and contrast the benefits of an academic versus an industrial career and demonstrate that each of us has something to offer, as well as things that we would like to change. The things that we do well and do not do well tend to be the exact opposites of you. Said another way, our weaknesses are your strengths and your strengths are our weaknesses.

But that does not mean you just give in to the industrial sector and assume you cannot be effective in attracting new people. Academia needs to understand how to sell themselves. Emphasize the positive and go at it very aggressively by letting recruits know they have choices when it comes to an academic, government, or industrial career. It all comes down to choices.

Steven F. Watkins, Louisiana State University: First, I would like to thank P&G for supporting our program. We have a nice relationship with P&G.

D. Ronald Webb: You are welcome.

Steven F. Watkins: Some of our folks are buried in your blue bars there. My question is, did you mention the National Consortium for Graduate Degrees for Minorities in Engineering and Science, Inc. internships that you support?

D. Ronald Webb: Thank you for catching this, but no, I failed to mention the Graduate Education for Minorities (GEM) program.

Steven F. Watkins: I would like to pump that program, and ask that the industrial sponsors of GEM consider upping the ante.

The GEM program is a national consortium. All of the companies in this room belong to it, each supporting from one to maybe two or three or four of these very portable fellowships—they are now four-year fellowships—to virtually any institution in the United States. So this is a way to bring minority students into programs. It supports their four years with tuition, a nice little stipend, and so on.

I would urge all of the industrial folks to think about doubling their contribution, if possible. But the point is that this is a global contribution to graduate education. It also could seed your recruitment, because these folks spend a summer in internship in your institutions, and a lot of those people go back after they have gotten their degrees. So it is a good feedback mechanism for you, it is wonderful for us, and it works.

Billy M. Williams, Dow Chemical Company: First, I have to commend P&G on an outstanding program from an industrial standpoint. I know that we in Dow have many similar efforts under way, and we are always running into you on campus.

D. Ronald Webb: Thank you, and I too am well aware of Dow’s presence during the campus interviewing season.

Billy M. Williams: A couple of points I wanted to make, and maybe just add to the record a couple of others—what I consider to be best practices or resources for future consideration.

In the K-12 arena, there is a group known as the National Science Resource Center (NSRC) based in Washington, D.C., which is sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution, the National Science Foundation, and the National Academy of Sciences. The NSRC is involved in K-12 educational improvement in the math and sciences. They do have a website, so I will refer you to that if you are looking at sponsorship and support for a very active K-12 support.

D. Ronald Webb: I would like to learn more about that. We will talk later.

Billy M. Williams: For my other point, you mentioned your affinity groups and employee networks. Within Dow, we have had in place the past several years companywide affinity networks. We now have a women’s innovation network, an Asian development network, an African American network, a Hispanic network, and a gay and lesbian network across the company, which we have found to be effective in providing the type of environment that you talked about and that has been discussed in other venues here.

These are supported quite heavily from the top in our corporation and have been effective in helping change the culture and environment across Dow Chemical Company.

D. Ronald Webb: Point well taken. Thank you.

Iona Black, Yale University. I was wondering if you have tracked your RTCI participants.

D. Ronald Webb: No, we do not track them but that might be interesting to do. I know many of them go on to industry, for example, Dow, DuPont, and Pfizer. Others have chosen academia as a career path, with one of our most recent RTCI alumni accepting an assistant professorship at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. But I cannot speak for all of our former RTCI participants.

Iona Black: I was in your first group. I was a second-year graduate student, so I thank you.

D. Ronald Webb: Thank you for sharing that.