1

Diversity: Why Is It Important and How Can It Be Achieved?

Clifton A. Poodry

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

National Institutes of Health

Over the years, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) has sought and supported programs to increase the number of underrepresented minorities participating in biomedical research. Indeed, the Division of Minority Opportunities in Research was established in NIGMS to support that mission.

Why is increasing the participation of minorities in biomedical research important to NIGMS and the rest of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)?

Unfortunately, there exists a substantial disparity in disease morbidity and mortality among subpopulations of the United States. Clearly, there are large segments of the population that have not fully enjoyed the benefits of the research that NIH has funded. The people in those populations are biomedically and educationally underserved. In 1998, the Clinton administration issued an initiative that set a national goal of eliminating, by the year 2010, longstanding disparities in the health status of racial and ethnic minority groups. One focus of that initiative is the training of investigators who come from minority communities.

Why focus on increasing the number of underrepresented minorities who are trained as biomedical researchers? Can the problems of health disparities not be solved as well by people of any ethnicity? Does representation matter?

THE NEED FOR MINORITY RESEARCHERS

One answer can be found in the reluctance of minority group members to participate in biomedical research or clinical trials. This reluctance is accentuated when few of the scientists doing the research or running the trials are themselves members of minority groups.

In her essay “Women, science, and society”1 published in 1998 in Science, Sandra Harding pointed out some benefits of diversity: “…these days, the presence of significant numbers of women in a field

often increases its legitimacy and the value of its work in the public perception.” She also wrote that “Gender diversity in policy-makers enhances the quality of decision-making in science and technology. To stress the importance of women’s perceptions and analyses, especially around issues that most affect them, is simply to point out that allowing for different viewpoints can have immense value in scientific and technological work.” Similar thoughts have been expressed with regard to the inclusion of minorities. These comments reflect the notion that representation in the scientific workforce matters because scientists, as individuals with their own points of view on what is important, make critical decisions for society on what should be studied and supported.

MAKING FAIR SELECTIONS

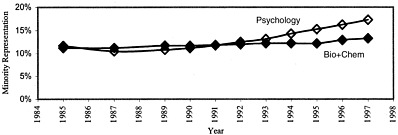

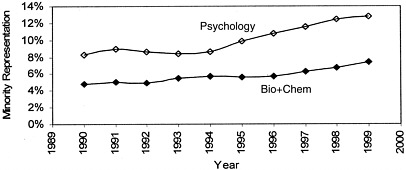

In recent years there have been gains in the number and percentage of minorities obtaining baccalaureate degrees in the sciences. Underrepresented minorities make up about 12 percent of the bachelor’s degree recipients in biology and chemistry (Figure 1.1). However, they make up only a little over 5 percent of the Ph.D. degrees awarded in those disciplines (Figure 1.2). It is important to recognize that

FIGURE 1.1 Minority representation among bachelor’s degree recipients in biology + chemistry and psychology (all U.S. institutions).

FIGURE 1.2 Percent of Ph.D.s in biology + chemistry and psychology awarded to underrepresented minorities (U.S. citizens and permanent residents).

the current underrepresentation of minorities in graduate science programs has occurred despite policies that were put in place to ensure fairness. That does not deny any unintended negative effects on minority groups, but it recognizes that academic decisions are based on the application of multiple, overlapping values. Whenever resources are limited, some people will be left out. In graduate admissions, for example, if there are more applicants than there are labs or graduate stipends, some applicants will not be accepted. Faced with that dilemma, admissions committees apply various criteria. One criterion is to select those who can best take advantage of the opportunity. A second is to select students who will quickly become assets to the research program of their graduate advisor and to the graduate program as a whole. In an effort to make unbiased judgments, graduate admissions policies gradually shifted toward the use of objective criteria in preference to subjective criteria in student selection. To remove the possibility of bias influencing the decision, dispensing with the use of subjective measures became a standard. As a result, standardized testing became an increasingly important way to be objective and fair. Conversely, current standards encourage a diverse and inclusive group of students in our training programs. Although objective testing may appear to have removed a source of overt bias, there is a great deal of uncertainty about what the tests measure and whether different communities are at a disadvantage in their abilities to perform on such tests.

Does support of our value of diversity necessarily mean that we must abandon objective standards designed to ensure fairness? A question that we have wrestled with for some time is how to increase opportunities for the development of a pool of underrepresented minorities without denying any opportunities to nonminorities.

In 1997, NIGMS convened a small working group to consider alternative criteria that might help guide the design of future Minority Biomedical Research Support and Minority Access to Research Careers programs so that NIGMS could meet the desired outcomes but avoid having race-restricted eligibility for the programs. The group considered alternatives to race and ethnicity, such as defining eligibility by a surrogate marker, such as disadvantage based on geography or quality of schools. The concept that emerged from the discussions was that programs should emphasize (1) the motivation and willingness of the participants to pursue training; (2) the motivation and desire to improve their skills and abilities; and (3) the provision of some service to underserved, underrepresented communities. The group members recommended that an advertisement for a program might say, “This program particularly encourages applications from individuals who have experienced and worked to overcome educational or economic disadvantage, individuals from underrepresented groups, and individuals who have other personal or family circumstances that may complicate their transition to the next stage of their biomedical research career.” The message to NIGMS was to devise programs that focus on outcomes rather than individuals.

AN ALTERNATIVE VIEW OF THE PROCESS

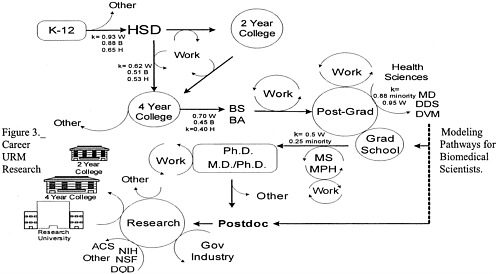

A metaphor that has been used over the years to describe the production of minority scientists has been that of a pipeline—a leaky pipeline. At NIGMS, we do not believe that a pipeline captures the essence of the way people develop in the course of their lives. We believe that the course of personal development is more like a complex chemical synthesis. Some reactants are moved along the pathway, but reaction products are also lost to our main pathway (Figure 1.3). Although there may be an enrichment step, it may be at the expense of substrate. This metaphor raises new questions. Do we know something about the rate of the reaction? Do we know something about the quantities and concentrations? Do we know enough about alternative pathways that, if somebody drops out on the way to a bachelor’s degree, we can predict if he or she will be likely to reenter the pathway or will they be lost? Perhaps most important, what are the catalysts that will help move reactions forward?

FIGURE 1.3 Modeling career pathways for URM biomedical research scientists, where k= fraction of students graduating per year by ethnicity, W=white, B=black, H=Hispanic. At each transition, the fraction of minority students who go on to the next level is lower than for nonminority students. Fractional completion rates derived from data found in Science and Engineering Indicators, 1996, NSF.

Figure 1.3 shows that transitions in academic progress differ among various minority groups. For example, if the high school completion rates for Mexican Americans and American Indians are only 50 to 60 percent, limiting our efforts to interventions at the college level misses a major part of the problem. Because the completion rate of Ph.D.s is lower for minorities than for nonminorities, another conclusion that can be drawn is that if the difference in completion rate were eliminated, the number of minority Ph.D.s produced would double.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Good examples of successful endeavors to develop minority scientists are included in the NIGMS booklet, Scientists for the 21st Century: Biomedical Research and Training Opportunities for Minorities.2 In it, three individuals are featured who have come through our programs and are doing wonderful things. We do have great success stories—the programs can work. Although we pride ourselves on these outstanding outcomes, we are concerned about the difference between the completion

|

2 |

National Institute of General Medical Sciences. 2000. Scientists in the 21st Century: Biomedical Research and Training Opportunities for Minorities. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health (http://www.nigms.nih.gov/about_nigms/more_brochure.pdf). |

rates for various groups and the overall low number of underrepresented minorities obtaining Ph.D. degrees.

When we ask how representation is different today from what it was 30 years ago, we are disappointed to find that we continue to have the same problems of underrepresentation. Consequently, our thrust is toward improving the ability of institutions to prepare and graduate increased numbers of minority students, as well as to promote the successes of the students.

In conclusion, at NIGMS we need to evaluate the effectiveness of our programs designed to diversify the scientific workforce and promote the most effective components. The activities highlighted at this workshop illustrate some of the outstanding positive examples. They should be studied and, where possible, emulated.

DISCUSSION

Isiah M. Warner, Louisiana State University: As I was listening to you talk, I thought about a study that reported that aspirins are now a good antidote for prostate cancer. When asked, researchers said 100 percent of the patients involved in the study were white males.

We in the minority community know that prostate cancer is much higher among minorities, African Americans, for example. It makes me wonder how, in this day and age, can studies not include a diverse population. It is just mind-boggling that those things continue to go on.

As we proceed through this workshop, I hope we will recognize that there will be some things discussed that people can use as a template so that they will not have to reinvent the wheel.

However, that aspirin study showed me that we have not learned from the past. I know that we are anxious on many fronts to try to make sure that there is a diverse population and that there are such studies, but I think we still have a long way to go.

Clifton A. Poodry: I will agree, and that is why we need a diversity of people—in gender, race, and ethnicity—at the table with those points of view, helping to influence policy.

C. Reynold Verret, Clark Atlanta University: Many of the initiatives at the NIH and the other agencies to increase the pipeline occur at the college and higher level. What programs do the NIH and other divisions have that reach into the high schools? A question that has come up at other meetings is how many of us opted for science while we were in college. That decision is actually made earlier. The paucity of the pipeline has to do with something that occurs much earlier. What is being done to address that issue?

Clifton A. Poodry: It is the Ides of March. Our authority, the NIH, is for research and for research training. Generally, that is not interpreted as meaning educational support or other activities at the precollege level. Although there are some experimental programs that address the question of motivation and preparation in high school, they are very small. At NIGMS, high school programs have been discussed a number of times, and we would love to have further discussions on them, but we have not done much. I think that unless the President or Congress told us to do more—that is, if our authority was changed—we probably will not. I absolutely agree with you, but we do what we can.

William M. Jackson, University of California, Davis: You pointed out two things. One was, if the graduation rate for minorities was increased to what it is for the majority students, it would double the overall Ph.D. production. How does that work out in terms of absolute numbers? How many minorities

are entering the Ph.D. program? As far as I know, the number entering is significantly lower than their percentages of the population. That is one issue.

The other issue, which I thought was interesting, was the criteria for judging students and faculty, and they are at odds with the outcomes that you want for those students and faculty, but you never suggested any new criteria for judging.

Clifton A. Poodry: No, I did not suggest new criteria. That is why I want to engage more minds in helping us with those criteria. I can give you some examples. One of the things that you want is someone who can be a multifaceted team player. I do not remember whether years ago if it was you that gave the example of a basketball player. I attribute it to you. Maybe it was somebody else. Well, you cannot have somebody who just shoots. The person may be wonderful, but that is not a basketball player. You cannot have somebody who can play only defense. You need somebody who is a balance. Not all faculty have to be high-scoring shooters or the best defensemen or passers. In fact, you need a team of people that have a variety of talents.

One of the things we want of a faculty in a college are people who can think about the issues, whether it is education, how to teach better, whether it is the research community, the community of scholarship, or the various other functions that we provide. Unfortunately, when we recruit new faculty, we seldom look at the attributes that are going to be important for them to be complete faculty.

David Bergbreiter, Texas A&M University: One of the things you did not mention that NIH does that I think they should be commended for is that, if you have an RO1 grant and if you have a minority student, you can add that student onto your grant basically at no cost. It adds an increment to your grant.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) claims to do this, but it is not as transparent. For NIH, that is very important. What that means is that a faculty member has an incentive to recruit minority students. For example, if a student has trouble in his or her second year trying to get through the semester, the principal investigator does not have to worry about using a significant percentage of the grant funds to support the student while the student figures out what to do with his or her life. It does not hurt the program very much. I think that is an important measure, at least for people involved in research.

Clifton A. Poodry: I appreciate that comment a great deal. It is ironic. We initiated that program at NSF nearly 20 years ago, and it is a shame that it has not blossomed. I am at least pleased that NIH has adopted it.

Patricia M. Phillips-Batoma, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign: You pointed out the importance of consulting literature on these issues rather than relying on personal experience.

I was wondering whether there might be a central agency somewhere that might be able to develop a website that has references to published literature in this area that people could consult readily.

Clifton A. Poodry: That is a terrific suggestion. In fact, if you go to the NIGMS website, one of the things you will at least find there is a small link to 20 top references. The University of Maryland, Baltimore County, put together a list for us. We had wanted to provide something just like that.

In fact, a list of 1,000 references was put together, but there are still hurdles. Some of those hurdles Isiah Warner may help us with. We should be helping the community by at least putting a lead out there. Take a chance. Put some titles out there, and, if people disagree, they will tell us there is a better one, but that is a way to get it started. It is a technical assistance that we can and should be doing. I hope we can follow up on that.

Robert L. Lichter, The Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation: I was glad you pointed out the importance of individuals taking responsibility. It seems to me that one of the best things that NIH and others can do is to enable individuals to engage and to become champions for change. In the end, that is what counts.

To what extent are NIH’s programs—your programs and related ones—taking into account the newest discussions relating to the lack of relationship between race and genetics? With the human genome project completed, there is a lot of discussion now showing that those things that we identify with ethnicity and race have little to do with health observations.

Clifton A. Poodry: Certainly that is a major continuing interest of the Genome Institute. NIGMS has a strong interest in that, not only because of the genetics division but also because of the pharmacogenomics program. We need to understand that the pendulum has swung from the belief that genetics was tremendously important to not important.

Clearly, we have genes and they interact with the environment. It is also true that people historically, from different geographies of the globe, have some differences. The amount of differences is much smaller than people might have thought ten years ago, but, nonetheless, there are differences and they may account for part of the reason that we react to the environment differently and have different susceptibilities. It is an important balancing act. We cannot lose the purchase that we have on being able to look at population genetics, but we also have to be cautious not to overascribe or to reinforce prejudice or stigma. That is one of the reasons why NIH has ethical, legal, and social-implications genetics programs, which both the NIGMS and the National Human Genome Research Institute subscribe to.

Donald M. Burland, National Science Foundation: NSF has a number of minority-related programs. In fact, any principal investigator can request a supplement to a grant for a minority graduate student or a minority postdoc.

There are minority planning grants, and a number of other programs, for a faculty member who needs to get those very important sort of preliminary results that always seem to be required to obtain funding. If I were to be critical of us, I would say that we have not done as good a job as we can to make sure that everybody knows about those opportunities. It is usually a small amount of money allotted per program officer, and it is limited by the amount of proposals that we receive.

Clifton A. Poodry: I appreciate your comments. When we started, Jane Paterson and I called every single grantee. We spent only about two-tenths of a percent of our budget. Our goal was to reach approximately half a percent of our budget. So, the budget was not the limitation. The limitation was, in fact, the number of applications that came in.

Josef W. Zwanziger, Indiana University: William Jackson raised this question about the absolute numbers, which we did not address.

If I remember correctly from the American Chemical Society data, the number of Ph.D.s per year in minorities is about 60. If I am wrong, please correct me. I think we just wrote up a report in our department about this, and I think that is the right number. Even if that number gets doubled, it is exceptionally small. I think that should be at least as big a concern as the actual rate of production, just because the numbers are very small right now.

Clifton A. Poodry: We have the numbers as of a couple of years ago. It is possible to download them from NSF databases. What I can tell you is that, if you combined biology and chemistry, and, unfortu

nately, psychology together, the number of baccalaureate degrees for minorities is currently about 16 percent.

That is the pool that is immediately available to go on to graduate school. The number obtaining Ph.D.s is closer to 10 percent. Actually, that is not so bad, considering that the slopes of the curves are running somewhat parallel. Unfortunately, if you take out psychology and just have biology and chemistry, the number drops back down to around 6 percent. That means that there is a disproportionate loss in the graduate program compared with the baccalaureates that are available. I agree that the absolute numbers are necessary. We can get them.

William M. Jackson: In that 16 percent, how many are foreign students who are classified as minorities? I think that is an important issue, and we need to know that number.

D. Ronald Webb, Procter & Gamble: If you look at chemistry students who were granted with doctoral degrees in 2000, U.S. citizens or permanent residents only, we are talking about 1,200 degrees being granted, with about 3 percent going to African Americans. In absolute numbers, African Americans received only 44 doctorate degrees in chemistry that year. Also for the year 2000, a little more than 700 doctorate degrees in chemistry were awarded to foreign national students, but I am unaware of how many of these would be classified as minority.

Clifton A. Poodry: If you add Hispanic, it is probably another 3.5 percent. So, it is probably 6-7 percent.

D. Ronald Webb: Right, if you look at Hispanic and African American combined, there were about 90 doctorate degrees in chemistry awarded to these two minority groups in 2000. These numbers are very low.

Michael P. Doyle, Research Corporation: You made some statements regarding affirmative action and then new criteria that would define motivation and other factors that would bring people into the scientific workforce.

There is a sensitivity to the term affirmative action. At the NIH, and especially at the NIGMS, with all its myriad of programs that provide great directed benefit to underrepresented minorities, is there a reevaluation criteria for both the allocation of resources and for the definition of what represents the population or the pool, given the changes in judicial actions and in government oversight?

Clifton A. Poodry: Yes, we are aware of the judicial actions, the risks. For our programming in general, we have a goal of increasing the numbers.

For example, for a program that major institutions can apply for, not just minority-serving institutions, we ask the program managers to come up with a plan that increases the numbers.

They can add students but they are not limited to adding minority students. They can add any student as long as they can come up with a plan to increase the numbers. In fact, I can just imagine a program that would be inclusive, that would bring the best of all groups together and, a lot like the Meyerhoff Program, establish an esprit de corps and a work ethic to work on important societal problems.

I welcome anyone that would do that. I think it would be self-selected. It would be an enrichment for minorities, but it would be self-selected. We asked institutions to make the judgment. We do say that outcomes are to increase the number of underrepresented minorities, and we also define, but we also give them the opportunity to define, underrepresentation.

There is one program that started out not at our institute, but that we received management of, that specifically says that students paid on it have to be underrepresented students. In that case, it is up to the institution to set that. For example, the University of Kentucky has argued and made the case that residents of Appalachia underrepresent all ethnicities. So, they have made a case. There is nothing that stops them from appointing people that they have indicated are underrepresented.

The state of California has made a case that Filipino Americans, not necessarily people who are from the Philippines but Filipino Americans, are underrepresented. So, in fact, in their programs, that is an allowable. It is a wiggly line, but we are very conscious of not denying people the opportunities.

Marvin Makinen, University of Chicago: I would like to raise an issue that I think is related to the part of your talk about raising the percentage of minorities completing Ph.D. programs. I am bringing this topic up because I would like to have some answers to this issue through the breakout discussion groups.

We have heard a lot about criteria and perhaps a need for “new criteria” in the selection of minority students for graduate study. I am not sure that we need new criteria. I would offer that perhaps we need to reweight the criteria that we presently use.

When one is in charge of a training grant, as I am at the University of Chicago, it is very easy to recognize applicant students who are strong candidates because they have high Graduate Record Examination (GRE) and high grade point average (GPA) scores. However, when one is dealing with students who have not had a tradition of focusing on higher education, I do not think that those criteria should be weighted in the same manner. Possibly other criteria are better indicators of probable success of completion of the graduate program.

This is a problem when it comes to trying to renew training grants. Faculty constantly worry over this issue because site-visiting committees look at the GRE and GPA scores of students accepted to the program.

If students are accepted with low GRE scores, as is often the case for minority students without a tradition of academic achievement, they lower the average, and the fear is that site-visiting committees mark that against you. On the other hand, if recruitment of minority students is not considered adequate by the site-visiting committee, this is also a mark against the program.

I want to know which studies have identified the factors that show a positive correlation with success in completion of graduate programs. Perhaps, for instance, it is better to weight the letters of recommendation, where someone has actually had a student in the lab and has seen the student work and knows that the student, in spite of initial difficulties such as poor study habits, is likely to complete the program because of his or her own personal commitment.

I believe that this is a critical issue to be addressed if one wants to increase the percentage of minorities getting Ph.D. degrees. It is not just numbers. The issue is how to identify those applicants who are going to make it through the program and the criteria to be used for their selection into the program.

Clifton A. Poodry: Excellent question. I wish I had access to the research, to the publications, and I think your point illustrates it. We need to know. We need good data to base decisions on. We need to have something that is good research—credible, believable, and publishable—that we can refer to. Currently, we do not have solid items to give you. Isiah Warner said that Steven Watkins will perhaps address that this afternoon.

Tyrone D. Mitchell, National Science Foundation: I am a program officer at NSF. I want to mention something that may cause many of you to say, this guy is really off the wall. One of the things that I am

concerned about is the use of the term minorities. I think I would like to challenge everybody to start thinking about moving away from that terminology.

To give you an example of my concern, we went to a group meeting at NSF to discuss working on issues to get more underrepresented persons into the pipeline in chemistry. In the meeting, some people were very vehement about what we are doing for the disabled. This group is underrepresented in some areas. I want to challenge us to use the term “underrepresented groups” in the workplace. The government, in its census, identifies about five or six categories of people that it tries to track, and Asians are in that category. We use underrepresented groups or underrepresented minorities because Asians are not underrepresented in the workplace even though their percentage in the population is small. However, they are underrepresented in the Chemistry Division at the NSF just as white males are underrepresented in certain administrative functions.

I think the use of the term underrepresented groups is quite a bit better, but we are probably not ready to start using this terminology especially in this workshop. We need to be more specific in trying to identify who are truly minorities. We have developed a lot of programs for women, and when you look at African Americans and women, they have one thing in common. For women, the bias is sexual, they cannot change their sex, and for African Americans, the bias is skin color and they cannot change their skin color. Some of the other minorities—Hispanics, Asians, and other groups—can leave behind the cause of much of the bias they receive (language, for example).

I think we ought to start looking at underrepresented groups and try to get people into those areas where they are underrepresented. I think the term minority is something that we might want to move away from in the future.