6

The Imperative for Leaders and Organizations1

Steven F. Watkins

Louisiana State University

Despite the title, I do not intend to offer any imperatives; what I will do is describe the development of our chemistry graduate program at Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge (LSUBR) over the past 10 or 12 years and offer it as an example for other graduate programs. I hope this will lead to some discussion afterwards.

In December 2001 an article appeared in Chemical & Engineering News (Figure 6.1) that described our program in detail; that article was based on a talk I gave a little over a year ago to the Chemical Sciences Roundtable. I would like to acknowledge my colleagues in the effort to improve minority participation in the chemistry department. Dr. Sibrina Collins was instrumental in getting the article published and for filling in some historical research. She is now at the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a strong advocate for the Minority Scientists Network. Dr. George Stanley is chairman of the LSUBR chemistry department recruiting committee. Dr. Isiah Warner is of course a key factor in the growth of minority participation in our graduate program. I was privileged to be director of graduate studies during the 1990s, when the program grew and developed into the nation’s leading producer of African American Ph.D. chemists.

First, I would like to put the program in a historical context; I will then mention events that happened exclusively at LSUBR and in the LSUBR chemistry department. Finally, I will discuss a few of the success factors, some of which are unique, but some of which may be portable to other programs.

My story starts with the famous case of Plessy v. Ferguson. At the close of the 19th century, Homer Plessy sued the East Louisiana Railroad for requiring separate, but purportedly equal, facilities for blacks and whites. Plessy argued that this requirement violated the 14th Amendment by abridging “the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” John Ferguson, a Louisiana district judge, ruled against Plessy, and the U.S. Supreme Court eventually upheld Ferguson. Justice Harlan, in his lone dissenting opinion, said that “separate but equal” did indeed undermine the 14th Amendment and would

FIGURE 6.1 What is Louisiana State doing right?

SOURCE: Chemical & Engineering News, December 10, 2001, 79(50):39-42.

actually delay full implementation of it. How right he was! The entire 20th century saw the struggle to overcome separate, but by no means equal, accommodations in education, housing, and the workplace, a struggle that continues to this day

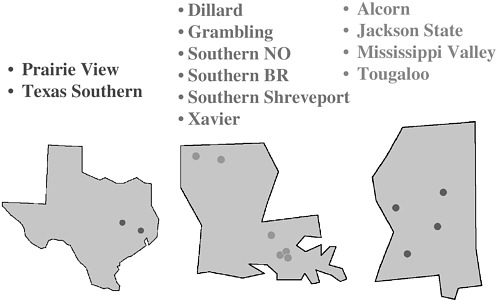

A consequence of this doctrine, at least in the deep South, was the growth and development of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), many located near LSUBR in Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi (see Figure 6.2). In Louisiana during the 20th century, most of the resources have gone to majority institutions such as LSUBR. More funds are now being allocated to HBCUs, but an equitable distribution of state and federal funds still has a long way to go. Nevertheless, these schools have done an incredible job of educating young black students with minimal resources.

Even after Thurgood Marshall argued successfully for integration in Brown v. Board of Education, blacks still were not welcomed, nor did they feel comfortable in majority white institutions. Certainly very few blacks came to LSU during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

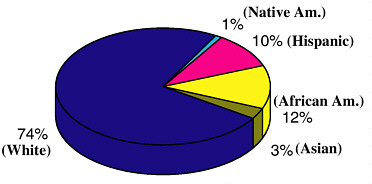

Even now the black population at LSUBR is very much out of proportion to the general population. The United States is approximately one-eighth African American. In Louisiana, that proportion is one-third. In East Baton Rouge Parish, where LSU resides, African Americans comprise nearly one-half of the population. With minority students representing only 26 percent of the student population at LSU as in Figure 6.3, the term “underrepresented” certainly applies.

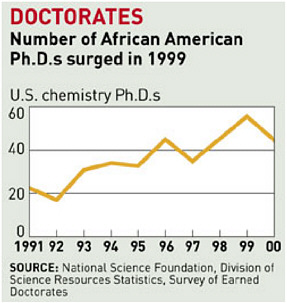

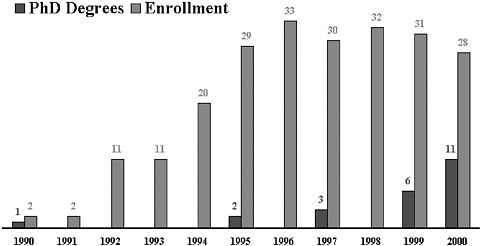

Figure 6.4 shows the small number of African American chemistry Ph.D.s produced in the United States since 1991. We at LSUBR believe we have contributed to the spikes in minority graduates at the end of the decade; in any case, the trend is definitely upward. The x axis in this figure represents the

FIGURE 6.4 African American chemists in the United States.

number of African American Ph.D.s graduating each year. This number is far better than it was 100 years ago. In fact, up to 30 years ago, it was traveling along in the binary mode, shown in ones and zeros. The number of graduates has certainly improved, but I think the message here is that we need to do more.

LSUBR is deep in the South and is an unlikely venue for our program as it has developed. For example, one of the first presidents of LSU was William Tecumseh Sherman, who resigned his post to join the Union Army and eventually wreck havoc on the South. To this day, Sherman’s name is not much in evidence on campus; William Tecumseh Sherman Memorial Hall is still far down on the list of buildings to be built. It is also ironic that both Isiah Warner, Vice Chancellor for Strategic Initiatives, and Greg Vincent, Vice Chancellor for Diversity, occupy offices in buildings named after Confederate generals.

It is not that LSUBR has been dragged kicking and screaming into affirmative action, because there have been a number of voluntary initiatives, but there have also been some definite actions taken by the courts. Some of these integration lawsuits are still in place and are monitored to date. Thus, many campuswide programs have developed in response to these actions.

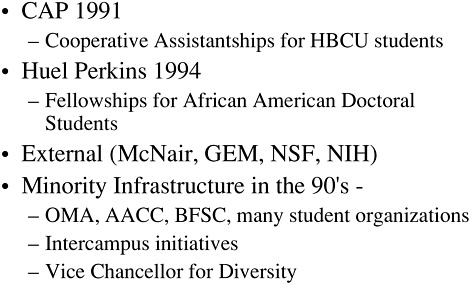

Figure 6.5 shows some of the developments on the LSU campus that began to occur in the 1990s. One of the first was a joint program with Southern University, an HBCU, called the Cooperative Assistantship Program (CAP). This was strongly championed by Dan Fogel, then assistant dean of the

FIGURE 6.5 Louisiana State University milestones.

graduate school and now provost. CAP was an assistantship program for black graduate students, primarily from Southern University, but it was expanded through the years to include students from a number of other HBCUs. The Huel Perkins Fellowship program was also the result of a desegregation lawsuit. Additional external funding is in place: McNair Scholars Program; National Consortium for Graduate Degrees for Minorities in Engineering and Science, Inc.; National Science Foundation; and National Institutes of Health, which have helped all graduate programs on campus significantly.

One of the great things that has happened at LSU in the past 10 or 12 years is the empowerment of minority students, faculty, and staff. The vice chancellor for diversity reports directly to the chancellor and the provost, the Office of Minority Affairs is an active and ongoing operation, the African American Culture Center is an active part of campus life, and the Black Faculty and Staff Caucus interfaces with and supports all of the student organizations.

Empowerment means that the students are able to network. One of the problems discussed earlier today in our breakout session was that black students, coming into some chemistry departments, did not know where to get old exams to study from. At LSUBR, both undergraduate and graduate organizations such as the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers and the Black Graduate Students Council provide a focus for information and activities.

There are also many intercampus initiatives with Southern University. There is cross registration between campuses, and a number of LSU students register for classes at Southern in addition to Southern students taking classes at LSU.

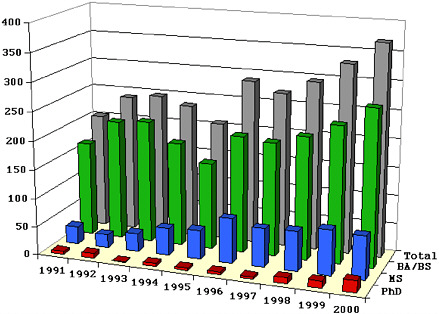

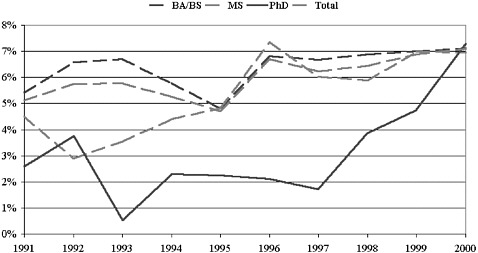

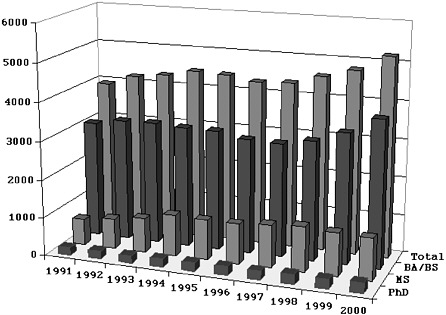

The overall program at LSUBR is a fairly massive educational enterprise. In 2000, approximately

3,000 bachelor’s degrees and 1,000 master’s degrees were awarded, along with several hundred Ph.D. degrees in more than 50 fields as shown in Figure 6.6. In contrast, Figure 6.7 shows the degrees awarded to African Americans: In 2000, approximately 250 bachelor’s degrees and 50 master’s degrees were earned. During most of the 1990s, the yearly Ph.D. degrees earned by African Americans could be counted on one hand. Clearly these numbers do not reflect the population of the United States, much less Louisiana. In fact, these numbers show that only 7 percent of each kind of degree awarded by LSU was earned by African Americans (see Figure 6.8). Note that LSUBR is the flagship university in a state that is 30 percent African American!

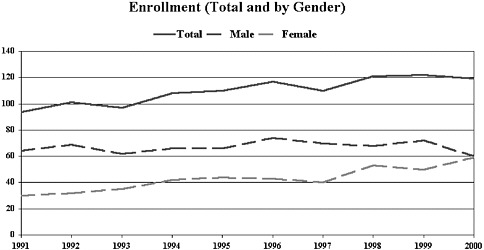

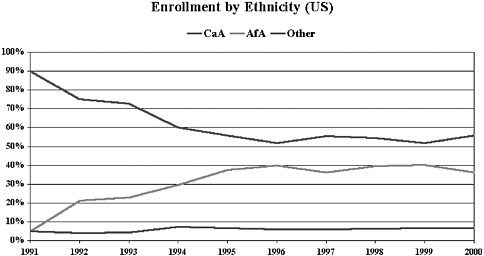

The chemistry department at LSUBR has changed during the 1990s, and to set the stage, I would like to put the program in perspective. First, notice that the total student population has been steadily climbing, shown in Figure 6.9 by the uppermost line. In 2000, the genders reached parity. Chemistry is no longer a male-dominated profession at LSU.

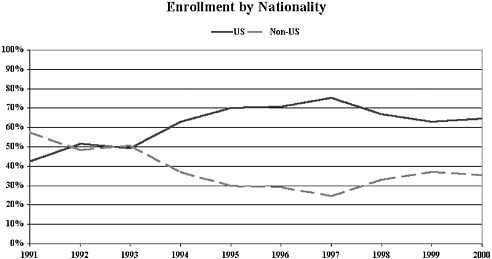

Figure 6.10 presents the yearly enrollment by nationality. In 1990 when I became director of graduate studies, the majority of our chemistry student body was composed of international students, and the largest international group was Asian. There is a huge pool of excellent Asian (predominantly Chinese) students that send hundreds of unsolicited applications to our program each year. However, at LSU, since 1990, we have made a concerted effort to recruit domestic students more actively to the program. We recognized that there were excellent students in HBCUs; they were not being recruited, and we needed a way to bring them into our graduate program.

FIGURE 6.6 Total Louisiana State University degrees.

Before 1991, only four African American students had been awarded Ph.D. degrees in chemistry at LSUBR. Richard Evans was the first African American Ph.D. (1971) in the history of the LSUBR chemistry department. He is now retired from Alabama A&M University where he was the chairman of the chemistry department for a number of years. Mildred Smalley (1972) is now vice chancellor for research and strategic initiatives at Southern University. Don Prier and Aris Gallon both joined the local Dow Chemical facility. The excellence of African American Ph.D.s had been proven; LSU simply needed to actually recruit these students for the graduate program.

Figure 6.11 shows the change in the domestic student body during 1990s, starting in 1990 with 90 percent Caucasian Americans, mostly male. Through the years, we have successfully recruited African Americans (see Figure 6.12). At present, the number of African American students in our department has reached between 30 and 40 percent of our domestic student body in the chemistry department.

Although we decreased the number of international students proportionately, we still have a very diverse population. International students now represent only 30 to 40 percent of our student body, but they come from more than 20 countries, making the chemistry department the most culturally diverse department on campus.

Isiah Warner joined the LSUBR chemistry department in 1992 and brought a number of his students with him from Emory. His presence and stature catalyzed a cascade of applications from African American students that has continued to this day. With his influence, one might think that all African American students come to LSU only to work for him, but in fact only four to five African American students are members of his group. All faculty members actively recruit these minority students; they have proven to be of excellent caliber, and they are productive researchers.

By 1995, the population of African Americans in the department had reached its steady state of about 30 students. Many of the students have indicated to me that, when they saw all of the black

FIGURE 6.11 Domestic student enrollment in chemistry by ethnicity.

FIGURE 6.12 African American student enrollment in chemistry.

students during their initial visit to the department, they felt very comfortable. Nearly every research group has African Americans in it, and this is an important factor in the success of our program.

From 1992 to 1994, the campus went through an induction to the minority recruiting program. Then, toward the end of the decade the Ph.D. degrees began to be awarded. Now, production of African American Ph.D. degrees continues at about ten per year, and we expect this to continue as long as we can maintain a high enrollment of African Americans in the department.

Figure 6.13 shows a list of the current graduate students and their undergraduate institutions. Schools like Grambling, Xavier, and Southern are well represented and are certainly regional, but in fact HBCUs and majority white institutions from all over the country are represented here. Thus, in terms of wide-area recruiting, the program is certainly successful. There are often measurable successes for the program as well.

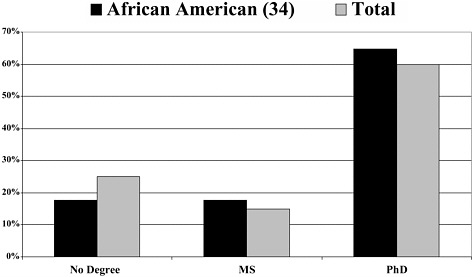

One measure of success is retention and degree attainment. African American students may actually perform slightly better than the overall student body, but the statistical universe is still too small to draw definite conclusions: About 60 percent of all students achieve the Ph.D., about 20 percent leave with a master’s degree, and the remainder leave the program with no advanced degree for a variety of reasons (see Figure 6.14).

If African American students do achieve at a higher rate than the total student body, there may be an “Avis effect”: we are number two, so we try harder. In any event, these students are producing some excellent work across the department in all research groups. In that sense alone, this program is a success.

Certainly the proximity of HBCUs has helped us to build this program. We are in the deep South. There are lots of excellent small schools nearby and the word is out. LSU is a comfortable place for

FIGURE 6.13 The African American student body in chemistry (2002).

FIGURE 6.14 Success rates for chemistry students.

African Americans to study chemistry. It is easy for us to go out and talk to these schools, and we always invite students to our campus because we think that is an important part of recruitment.

Perhaps the most important factor in our program is the achievement of a critical mass of students who share a common ethnic and cultural heritage. An African American undergraduate who is visiting

a graduate department has to be comfortable; if he or she sees only white faces, then they probably will feel uncomfortable simply because there is nobody around to talk to, who speaks and understands their language, and who shares their background.

In addition, LSU does not put much value in general GRE scores. We have found over the years that the GRE is not a good predictor of success in graduate school, and we have been able to convince the dean of the graduate school that it is not a good indicator, particularly for minority students. As a consequence, the graduate school has given us some flexibility in accepting students with lower GRE scores. A good GPA and good letters of recommendation are better indicators of a student’s ability to excel. This is very important to us because we want to know how the student has done, how they have interacted with others academically, and what research experiences they have had.

The LSU chemistry department has lots of built-in support for African American students. We certainly have achieved a critical mass. And the recruiting is almost self-sustaining; the students almost recruit themselves: In fact, we often ask graduate students to accompany faculty on recruiting trips to their alma maters.

Mentoring and support are extremely important (see Figure 6.15). The faculty have to be willing to help those students who may have a little trouble with some of the courses at the start of their careers. If a student wants to do chemistry and if he or she has had some experience and has been nurtured at a good school, the faculty have to be willing to help them along. In short, the sink or swim attitude has proven to be very counterproductive.

We also think it is extremely important to have in place black faculty who will be role models and who will simply make the students feel at ease. Minority students often feel more comfortable, at least

FIGURE 6.15 Factors in recruiting and retention.

initially, talking to a minority faculty member. Later, he or she becomes comfortable talking to all the faculty.

Unfortunately, there are not enough minority faculty members available for all the graduate programs in research universities. That is a serious problem for our country; a faculty that has no African American presence is going to have trouble recruiting and retaining African American graduate students.

For a program like this to be successful, the faculty has to believe in it. This was not the case in the beginning at LSU. There was some resistance to diversification from the faculty and from the majority white students. This resulted in a departmental workshop. Isiah Warner was chairman at the time, and he brought together the faculty and graduate students for a two-day meeting. We are a better department from the workshop process, but nevertheless, it was a painful step to take.

After that workshop, most people believed that diversification was going to lead to success—their success. Indeed, what we found was that the African American graduate students who came in with McNairs, Graduate Education for Minorities, Huel Perkins Minority Fellowships, and Career and Placement Service Fellowships had larger salaries than the majority students. The majority students started to agitate about this, and pretty soon their salaries went up. All of the students were cognizant of this chain of events; the interrelationship between the minority and majority students in our department has been very healthy and has led to higher salaries for all.

Employability almost goes without mention. Other schools, industrial labs, and government agencies are thirsting after minority students. When new students interview for positions in our graduate program, they know there will be a job waiting for them at the end of their long hard struggle. This benefit extends beyond the minority students. Companies like Dow and Proctor & Gamble come looking for minority graduate students; but with the overall pool of available graduate students who interview, majority students are offered jobs too. It is a win–win situation. We now have much more on-campus recruiting, and increased employability is definitely a success factor.

Approximately half of our minority Ph.D. students go into industry. The remainder are evenly divided between academics and government labs. What concerns me is the one-quarter that enter academia. How are we going to change the low number of minority academic positions if we are sending a majority of our students to industry? I am not suggesting that they avoid industry because they do earn better salaries. However, I am suggesting that the professoriate is not being served, and although I offer no solution, it might be worth discussing.

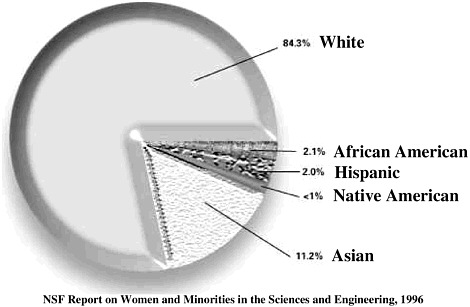

Figure 6.16 shows workplace demographics in 1996, but there probably has been some change in five years. Clearly, the workplace is still majority white, but over time, the small wedges are going to get bigger—we at LSU are working on it, and I know all of you are too.

LSU is doing some things right. We do not have all the answers, but we have, partly by chance but mostly by hard work, developed a diverse and productive chemistry graduate program. We have had many excellent minority students who are productive researchers, but are also active in departmental committees and on the Graduate Student Council. Some are also active in the Baton Rouge community, in such things as K–12 outreach and National Chemistry Week activities. In short, these students have enriched both the department and the university with their presence and will no doubt continue to be highly valued professionals and citizens.

DISCUSSION

David Bergbreiter, Texas A&M University: In your discussion, you mentioned an interview for

FIGURE 6.16 Workforce demographics in 1996.

SOURCE: Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering, 1996, NSF 96-311.

graduate students. Where, in the recruitment process, does the interview take place? Is it before or after they have an offer, on campus or off campus? Can you explain that in the context of graduate recruiting?

Steven F. Watkins: After the application has been made, we generally ask the students to come in before we give any offer. We do not generally make offers until we see and talk to the students and look at their credentials. We then invite the student to visit for a day, sometimes two, and to meet with each faculty member individually and personally. We do not have group interviews because nobody likes them. Occasionally, if a student’s credentials are good and he or she looks great in the interviews, we will produce an offer letter and give it to them in person.

David Bergbreiter: This interview process is something that you do only for the African Americans or is it something you do for everybody?

Steven F. Watkins: We do this for all domestic students, but it is particularly important for the African American students.

David Bergbreiter: You are actually the only place I know of other than Scripps that does this.

Derrick C. Tabor, National Institutes of Health: Could you comment on the presence of LSU faculty members at HBCUs, in terms of their seminar presentations, the nature of the interaction with their faculty colleagues, and especially their visits to the HBCUs as opposed to the HBCUs’ visits to LSU.

Steven F. Watkins: Good question. I am sorry to say that we do not do as well with that as we should. Isiah Warner is a great traveler and promoter.

Derrick C. Tabor: The white faculty.

Steven F. Watkins: The white faculty do not do as well with that as we should. Back before Isiah Warner showed up, I was traveling around and going to the HBCUs. You would be surprised—maybe you would not—by how much credibility a white man has in an HBCU. It was a good experience, and we did get some students that way. Locally, recruiting is easy. We have good relations and research collaborations with Southern University, Xavier, and with the other HBCUs that are close by, but the white faculty do not project the proper image.

Kristen M. Kulinowski, OSA/SPIE Congressional Science Fellow: I have to applaud you on the remarkable success of your program. It speaks to the importance of creating a comfortable environment for minority students.

I know that the subject of women was the topic of last year’s chemical roundtable. I was given an article (by another person in the audience) describing last year’s Chemical Sciences Roundtable workshop on women in the chemical workforce. It stated that the presence of faculty wives helped to create a comfortable environment for prospective women students.

I believe that just as Isiah Warner’s presence catalyzed a comfort level for African Americans, women faculty role models, rather than spouses, should be doing the same for women students.

One of the barriers [to retaining underrepresented groups in academia] may be that the academic environment is not seen as friendly on the faculty level to certain types of people.

Again, referencing the chemical sciences roundtable workshop in 2000, Debra Rolison made that point that the academic community, at the faculty level, is not creating a hospitable environment for certain types of people who may be excellent scientists but who do not fit well within a certain type of academic structure.

Can you comment? Is LSU doing anything at the faculty level to help promote these role models?

Steven F. Watkins: Specifically with reference to gender issues, we have been fortunate, just within the past couple of years, in fact, to bring on four women faculty.

Kristen M. Kulinowski: Out of how many?

Steven F. Watkins: Out of about 30. Before they arrived we did not have any tenure-track women faculty. In fact, one of these women, who was a postdoc at National Institute of Standards and Technology and who, I am sure, worked day and night as a postdoc, mentioned to me one day that her work load had gone way up at LSU because all of the women graduate students wanted to talk to her about their problems. The central idea is that every group has to be comfortable in the academic environment. I do not know how you do it for every group. You identify and try to make provisions for women, for international students, for minority students. The white males can fend for themselves, I suppose.

Kristen M. Kulinowski: The question was more about the faculty and how you make the women faculty members feel comfortable and successful so that they can help the students.

Steven F. Watkins: Again, I think it is a question of critical mass. If you have one woman in the department, she is going to be very lonely. Two women is good, three is better, and so on. We are fortunate enough to have two African Americans in the department. We have an adjunct, Saundra McGuire, who is also a part of this process. Isiah Warner is the one male faculty member right now, but we need more.

Clifton A. Poodry, National Institutes of Health: Your results are very encouraging. You are to be applauded for this effort. Do not take my next question, though, as too much of a criticism, but I would like to probe deeper. Are you, in the greater scheme of things, doing well? We have all sorts of birds in our backyard because my wife puts out suet and bird seed, but this does not make a difference to the birds. They are there for our enjoyment because we have attracted them to our lawn, but if we did not put food out, the birds would be doing just as well. So, you have created an environment, a hospitable place that welcomes the students. Your numbers have gone up. Do you have a sense, do you have a way of knowing, in the greater scheme of things, whether you are doing well?

Steven F. Watkins: I do not know how to answer that. I think in a graduate program we are dealing with small numbers of students. We are not dealing with thousands. We are dealing with dozens.

My sense is one success at a time is okay. One productive Ph.D. who goes out and makes a contribution to society is a success. Are we doing well overall? The numbers are impressive, but would these students have gone someplace else to get Ph.D.s? There is no control.

Isiah M. Warner, Louisiana State University: I think we have some data. For example, let me tell you about the Victor Vandell story. He is a young man whom I happened to find at Chicago State University. He worked while he was an undergraduate, had about a 2.6 grade point average, went on to do graduate work at RIT—I think he had a 3.1 average in graduate school. I found him at Chicago State as a lecturer. I was sitting there talking to this young man, thinking to myself, this is an incredibly bright young man. So, I talked to the chairman, “Yes, he is very bright,” said the chair. He had a poor undergraduate record, but he was working full time while in school full time.

I came back to the LSU faculty and told them about this young man and about his record. They said, “We don’t want to see this young man. We have completed all of our recruiting for the year.” I told them to just interview him. So, we brought him in and interviewed him. The faculty were so wowed that they made him an offer on the spot. Five years later, he graduated with a Ph.D. He went on to start his own company. He was the greatest ambassador for our department and he was all over the campus. Everyone on campus knew him. He did phenomenally well in our program. There are a lot of schools that would not have taken a chance on him. He is an extreme example; however, there are a number of other examples like that, of students that we took a chance on, and some of them are extraordinary students.

We now have companies beating on our doors. For example, Dow Chemical interviewed a few of our students. Previously, corporate headquarters told Dow Plaquemine, across the river from LSU, not to recruit at LSU because they wanted to recruit at a top ten university. Later, headquarters called and asked, “What is going on at LSU? Why aren’t you guys recruiting there?” Dow Plaquemine said, “Because you told us not to recruit there.” They said, Well, get on down to LSU and see what is going on there. We just interviewed these phenomenal students.

I will give you another example. I had two students who graduated from my group, both African Americans. A Dupont recruiter said that, regardless of what criteria he would have used—academic skills, gender, race, any criteria—those two students would have finished in the top 5 percent of his recruits. So not only are we taking students that some schools might consider marginal, we are producing a phenomenal product. That is why these companies are beating on our door. It is simply because they see a product that is incredible and suits their needs. They do not know the background. They do not know what we started out with. I think we are doing more than just pushing students through who would not have survived at other places. Although I am certain these are students who would not have made it at MIT or Berkeley, our close interactions with the students make an outstanding final product.

Iraj B. Nejad, National Science Foundation: I would like to applaud your effort as well and then ask a short question. If I understood it correctly, you showed a slide that said that about 7 percent of all degrees offered are to African Americans.

Steven F. Watkins: That is correct for the overall LSU population.

Iraj B. Nejad: That is not representative of the Louisiana population, which is 30 percent African American. My question is, with all the efforts that you have in place—mentors, a committed faculty, a committed department, self-sustained recruiting—what else would it take to bring that percentage up?

Steven F. Watkins: All the HBCUs would have to close down. HBCUs are still a good venue and value for many undergraduate students. Undergraduates have alternatives, but graduate students do not; that is why we are succeeding in the graduate arena. The trend is upwards at LSU.

Robert L. Lichter, The Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation: Isiah Warner’s last description reminded me of the comment that was made early in this workshop by Dr. Makinen: The focus has to be on the output, not on the input. If we restrict ourselves to the traditional methods of evaluation that focus on the input, we are not going to get the kinds of results that we are seeing.

Obviously you have challenged the traditional model for recruitment of graduate students and have succeeded in it. Are you doing anything more with the larger questions of graduate education taken broadly, challenging or revisiting traditional models, dealing with the kinds of issues that were brought up at an earlier workshop in this venue and that are going on now in other places in the country? It seems to me that you have a great opportunity.

Steven F. Watkins: We are probably not doing as well in that area. We have focused on recruitment and retention in this program, which is fairly traditional. We need to think about that; maybe we need your help.

Joseph S. Thrasher, University of Alabama: I, too, would like to commend you for your efforts.

I am curious about a question you raised. I am sure we do not have time to get the answers now, but I would like to hear any ideas on how to improve the professoriate to make more of these students want to pursue the academic career path. Perhaps industry has some interesting ideas.

I would like to close with one observation or comment. I am sure everybody in this room is convinced about the need to recruit minorities in science, but I think we need to do more to get the word out. There are a lot of people out there who obviously are not convinced how acute this underrepresentation problem is.

I can give you a personal example. A couple of years ago I was lead author on a Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need proposal. I quoted some of the same data you did on an early chart, in terms of African American Ph.D.s per year in chemistry. One of the referees wrote back that these data are surely incorrect and the number of students cannot be that small.

Jessica Arkin, Ventures in Education: We received permission to provide you with information about the Ventures Scholars Program. The Ventures Scholars Program identifies high-achieving high school and undergraduate students from traditionally underrerpresented groups and provides them with recognition and information that will increase their chances of entering careers in medicine and the allied health professions, science, engineering, and mathematics. This is accomplished by partnering with a consortium of undergraduate and professional institutions nationwide and providing opportunities for these institutions to recruit, enroll, and prepare targeted students for these professions. We work closely with the College Board to target these students based on preliminary scholastic assessment test scores and GPAs.

Recently, we started working with our undergraduate Ventures Scholars who were seeking to go into graduate programs. If you are interested in obtaining a database of these students, please call us at 1-800-94-SMART, extension 103.

C. Reynold Verret, Clark Atlanta University: What is being done to replicate these efforts in the other departments in our schools?

Isiah M. Warner: That is part of my charge in my new position. The chancellor and I were talking. He said, if we had sat down and talked ten years ago about being the nation’s leading producer of Ph.D.s in some area, chemistry for sure would never have been the area we picked. If we can do it in chemistry, we can do it in any area. One of the charges of my new position is to try to create the same kind of environment in other graduate programs.