Appendix F

Unit Dose Reconstruction for Task Force WARRIOR at Operation PLUMBBOB, Shot SMOKY

F.1 INTRODUCTION

This appendix presents an evaluation of a unit dose reconstruction for a participant group called Task Force WARRIOR at Operation PLUMBBOB, Shot SMOKY at the NTS (Goetz et al., 1979). The committee’s evaluation focuses on development of a plausible exposure scenario for members of the task force who received unusually high external doses. In dose reconstructions for atomic veterans, assumptions about exposure scenarios are of paramount importance for obtaining credible upper-bound estimates of dose for use in evaluating claims for compensation for radiation-related diseases (see Section I.C.3.2 and introduction to Chapter IV).

F.2 ACTIVITIES OF TASK FORCE WARRIOR AT SHOT SMOKY

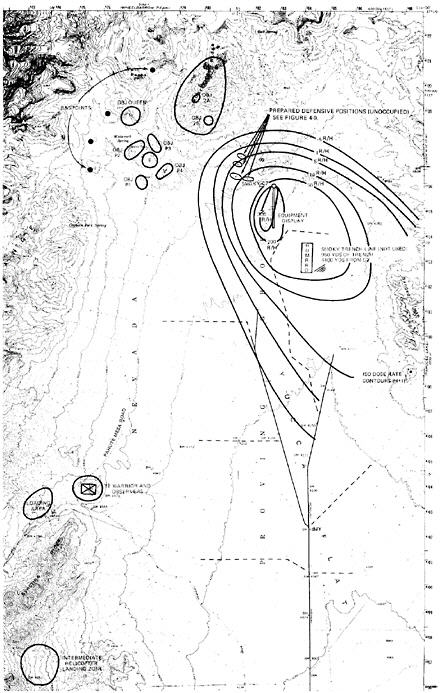

The discussions in this appendix concern only particular activities of Task Force WARRIOR in the first few hours after detonation of Shot SMOKY, specifically attempts by two units of the task force, the 2nd and 3rd Platoons of Company C, to reach the objectives of a planned maneuver shown in Figure F.1. Activities of interest are summarized in the following paragraphs (Jensen, 1957; Harris et al., 1981). The exposure-rate contour lines shown in Figure F.1 are discussed in the next section.

Shot SMOKY was detonated on August 31, 1957, at 0530 hours in Area 8, shot tower location T2C (see Figure V.C.6 in Section V.C.3.2). Some units observed the detonation at a location about 12 km south-southwest of ground zero (GZ) indicated in Figure F.1, and they moved to the nearby loading area shortly

FIGURE F.1 Map of maneuvers of Task Force WARRIOR at Operation PLUMBBOB, Shot SMOKY (Harris et al., 1981) (approximate scale: 1 cm = 1.14 km). Exposure-rate contours at H + 1 hour in R h−1 (“R/H”) are as given by Hawthorne (1979). However, assumption that contour lines were closed to northwest of ground zero was not based on measurement and was not confirmed by later survey data (REECO, undated); see Appendix F.3.

thereafter. Beginning shortly after 0700 hours, those units were transported by helicopter to landing sites about 5 km west-northwest of ground zero. By 0740 hours, the 2nd and 3rd Platoons had landed and seized Objectives P3 and P4.

At 0830 hours, the 2nd and 3rd Platoons were ordered to attack and seize Objectives 2A and 2B, which were on Quartzite Ridge about 4.5 and 3.5 km northwest of ground zero, respectively. The two platoons immediately moved to accomplish those missions. The next report of activity was at 0915 hours, or 45 min after the assault began. At that time, the commander of Task Force WARRIOR reported to the battle group commander that “the 2nd and 3rd Platoons, attacking to seize Objectives 2A and 2B, had advanced to the points permitted by [radiation safety] personnel and had been halted prior to seizure of Objective 2” (Jensen, 1957). At 0935 hours, a request was made for delivery of water to the west slope of Quartzite Ridge to supply the troops in that area. The last report of activity was at 0945 hours, when the exercise was terminated; the request for water was not honored for this reason.

Termination of the exercise 45 min after the assault on Objectives 2A and 2B began was unexpected because planning for the exercise called for resupply of the objective area by helicopters “for a period of not less than two days” (Jensen, 1957). The request for delivery of water noted above presumably was part of the plan of normal resupply.

F.3 RADIOLOGICAL CONDITIONS IN MANEUVER AREA

At the time Shot SMOKY was detonated, surface winds were calm, and winds above about 6,000 ft (1,800 m) were from the north and northwest (Hawthorne, 1979). Thus, as anticipated during planning for the test and post-shot maneuvers, the pattern of fallout near ground zero was mainly to the south and southeast. The exposure-rate contours at H + 1 hour shown in Figure F.1 (Hawthorne, 1979) were based on survey data at H + 8 hours and at 1, 3, and 5 days after detonation (REECO, undated). However, it is important to emphasize that survey data were not taken in the vicinity of Objectives 2A and 2B on Quartzite Ridge, because of rough terrain in the area, and the assumption in Figure F.1 that exposure-rate contours were closed to the northwest of ground zero (that is, that there was no significant fallout beyond the contour lines in this direction) was not confirmed by the later surveys (REECO, undated). Thus, survey readings do not directly address the question of whether there was significant fallout at locations of the planned assaults by the 2nd and 3rd Platoons.

Reports of activities of the 2nd and 3rd Platoons during their assaults on the two objectives on Quartzite Ridge, as described in the previous section, provide compelling evidence that these units encountered unexpected radiological conditions. The assault was halted before they seized their objectives (and much sooner than planned), and this action was taken by radiation-safety personnel who accompanied the platoons and monitored radiological conditions during the assault.

There is no apparent reason that the exercise would have been terminated if the expected low levels of radiation had been encountered.

Another interesting aspect of the early phases of the exercise was the apparent presence of a dense dust cloud produced by the blast wave of Shot SMOKY. At 15–18 minutes after detonation, the first helicopters left an assembly area about 25 km south of ground zero and headed toward landing sites west-northwest of ground zero. The task of the pathfinder team in the initial landings was to determine that radiological conditions would permit deployment of troops in the task force who awaited transport at the loading area. A report of the initial helicopter flights (Jensen, 1957) includes the following statement:

The pathfinder serial was forced to deviate from its proposed flight path because of a dense smoke and dust cloud which lay between it and the objective area. Taking advantage of a west wind which was beginning to move the cloud back in the direction of ground zero, the flight flew around the cloud and landed in an eastern approach, on appointed landing sites under conditions of visibility that did not exceed 800 yards … Visibility did not permit the establishment of the designated release point for a period of 30 minutes after the pathfinder landings.

Because the pathfinder team landed at 0617 hours, dust evidently was a problem for more than an hour after detonation, and some dust could have persisted after the 2nd and 3rd Platoons landed at about 0715 hours.

In addition, an aerial survey team that began making measurements one-half hour after detonation observed large dust clouds in the area of ground zero “which persisted for several hours” (Harris et al., 1981). The presence of an extensive dust cloud is significant because the area affected by the blast wave from Shot SMOKY was contaminated by fallout from previous shots, including PLUMBBOB Shots BOLTZMANN, DIABLO, and SHASTA (see Table IV.C.1 in Section IV.C.2.1.1 and Figure V.C.6 in Section V.C.3.2).

F.4 DOSE RECONSTRUCTION FOR TASK FORCE WARRIOR

This section describes aspects of the unit dose reconstruction for Task Force WARRIOR (Goetz et al., 1979) that apply to the 2nd and 3rd Platoons that assaulted Objectives 2A and 2B on Quartzite Ridge. The chronology of events up to when the exercise was halted by authority of radiation-safety personnel who accompanied the platoons is as described in Appendix F.2. The dose reconstruction then included information described in the following paragraphs.

Section 2.6 of the report documenting the dose reconstruction (Goetz et al., 1979), which describes operations on the day of Shot SMOKY, includes the following statement:

The extent of fallout patterns … indicates that [the radiation safety] criterion should not have been a factor in halting the advance, if the path of the assault was as planned. Because the planned path of direct assault would have encoun

tered some very steep slopes, the assault may have deviated to the south and east. This excursion could have led the 2nd Platoon toward the SMOKY fallout field where residual radiation levels were sufficient to cause [radiation-safety personnel] to halt the attack.

The fallout patterns referred to in that statement include the exposure-rate contours at H + 1 hour in Figure F.1. It is again important to emphasize that the assumption that the contour lines were closed to the northwest of ground zero and did not extend as far as Quartzite Ridge was not based on measurement shortly after detonation and was not confirmed by later surveys (REECO, undated). The 2nd Platoon assaulted Objective 2B from Objective P4 in the landing area.

Section 6 of the report by Goetz et al. (1979) discusses film-badge dosimetry for Task Force WARRIOR. Film-badge records for members of the task force were available for use in dose reconstruction. The report notes that many participants were issued two film badges, the first covering pre-shot operations up to August 27 and the second covering the period from August 27 to September 2, including operations on the day of Shot SMOKY.

The analysts noted that the film-badge readings cluster into two groups (Goetz et al., 1979). In the first cluster, which included about 95% of the film badges, doses for the period covering pre-shot operations (390 ± 150 mrem) were about twice the doses for the period covering operations on shot day (185 ± 60 mrem), indicating that most of the dose was due to exposure to residual fallout from the prior PLUMBBOB shots noted in Appendix F.2. In the second cluster, which included 20 film badges, doses for the period covering operations on shot day (1140 ± 150 mrem) were nearly 3 times as high as doses for the period covering pre-shot operations (405 ± 130 mrem). The agreement of pre-shot doses in the two clusters was noted, and the report also discusses how the film-badge readings during the first period are in reasonable agreement with estimates of dose that were based on the exposure-rate contours for the previous shots that deposited fallout in the area (Hawthorne, 1979), knowledge of the locations and times of activities of members of the task force, and assumptions about decreases in dose rates from deposited fallout over time.

Goetz et al. (1979) discuss the cluster of 20 unusually high film-badge readings during the period of operations on shot day. Those doses ranged from 800 to 1,400 mrem, and there was evidence that the spectrum of radiation was similar in all 20 badges. On the basis of that information, the analysts inferred that the 20 badges were worn by members of a group that stayed together during the operation, and their doses were assumed to apply to members of the 2nd Platoon, which was supposed to assault Objective 2B. On the basis of the presumption that the high doses were received on the day of Shot SMOKY, the report states (Goetz et al., 1979) that:

[I]t follows that the group would have been closer to SMOKY [ground zero] than the task force as a whole. Nowhere else on 31 August could the 800 to 1,400

mrem dose level have been achieved unless the group was subjected to the radiation field of SMOKY itself. It could be postulated from the film badge evidence …that [a group] could have proceeded due east from the objective area toward Smoky Hill and the Phase I positions instead of assaulting Quartzite Ridge to the northeast. Whether such an excursion was by oversight or design is immaterial. In either case, it is undocumented. The excursion would explain, however, why the assault was halted due to [radiation safety] considerations, presumably at the 500 [mR h−1] level. An examination of the SMOKY residual contamination contours would support this hypothesis—the group would have halted short of Smoky Hill near the Phase I defensive positions, having proceeded less than two miles in about 45 min…. They could have remained in the vicinity of the 500 [mR h−1] line until exercise termination at 0945, inspecting the post-shot damage to the defensive positions… If they had adhered to the 500 [mR h−1] limit, had not encountered any hot spots, and had departed promptly at exercise termination, their total dose from this excursion would have been about 300 mrem. They may have encountered hot spots, however. It is also possible that they ventured toward the close-in positions where intensities were greater, or stayed long enough to view all the positions. Given the uncertainties of this excursion, doses on the order of 1,000 mrem cannot be ruled out.

The Phase I defensive positions noted in these statements are the positions (trenches) within about 1,850 m northwest of ground zero shown in Figure F.1. The presumption that the excursion was halted when the exposure rate exceeded 500 mR h−1 may be questioned because a later report states that the limit for maneuver troops probably was 10 mR h−1 and that an exposure rate of 100 mR h−1 defined full radiological exclusion areas (Harris et al., 1981). However, such discrepancies are not important when doses are measured by film badges.

Finally, the analysts developed an upper-bound estimate of external dose to individual members of Task Force WARRIOR of 1,530 mrem based on film-badge readings during pre-shot and post-shot phases of the operation. In discussing the upper-bound estimate, the report notes that “if the group of 20 [film badges] are excluded due to evident incompatibility with the troop movements as known, the film badge equivalent of the upper exposure limit compares favorably with the highest combined film badge readings for any individual” (Goetz et al., 1979). The term “film badge equivalent” refers to a reconstructed dose based on exposure-rate contours estimated from survey data, as described previously.

F.5 DISCUSSION OF EXPOSURE SCENARIO ASSUMED IN DOSE RECONSTRUCTION

In reconstructing external doses received by the two platoons that assaulted objectives on Quartzite Ridge, the committee believes that it is reasonable to assume that the 20 film badges discussed in the previous section that had unusually high readings for the period including the day of Shot SMOKY were worn by

members of the 2nd Platoon, as assumed in the dose reconstruction (Goetz et al., 1979).

The essence of the analysts’ explanation of the unusually high film-badge readings, as given in the previous section, is that the 2nd Platoon disobeyed orders, either deliberately or inadvertently, and went toward ground zero instead of the planned objective. The reason given is that the planned path of assault on Objective 2B would have encountered very steep slopes and that a substantial deviation from the planned path of assault is the only way that unexpectedly high radiation levels could have been encountered, according to an assumption that the exposure-rate contours shown in Figure F.1 adequately describe the radiation environment to the northwest of ground zero.

The committee does not believe that the analysts’ explanation of the unusually high readings on the 20 film badges is credible. There is no documentation that either of the two platoons encountered inaccessible terrain in assaulting the objectives. Furthermore, Figure F.1 indicates that the steepest terrain lay beyond the locations of the objectives. It also does not seem reasonable that the objectives would have been placed at locations that were inaccessible by direct assault, especially inasmuch as two plans for the exercise were rehearsed in advance (Jensen, 1957), as acknowledged in the dose reconstruction (Goetz et al., 1979). The committee also notes that a deviation from the planned path of assault by the 2nd Platoon to an extent sufficient to approach ground zero, instead of Objective 2B, would have required a change in direction of about 90°. Such a large deviation was not required to avoid steep terrain.

It is, of course, possible that the 2nd Platoon deliberately disobeyed orders and marched toward the defensive positions (trenches) much closer to ground zero and therefore encountered higher radiation levels. However, such an action would have entailed substantial risk of discovery with no evident benefit, given that maneuver units were to be resupplied regularly (Jensen, 1957) and that their absence from the area of the objectives would have been noticed. The committee does not believe that it is reasonable to assume that military units deliberately disobeyed orders unless there is documented evidence of such actions.

F.6 ALTERNATIVE EXPOSURE SCENARIO FOR TASK FORCE WARRIOR

The committee believes that there is a plausible explanation for the unusually high film-badge readings that apparently occurred for members of at least one of the two platoons during the aborted assault on Objectives 2A and 2B on Quartzite Ridge. This explanation does not require assumptions that a platoon did not follow the plan of assault, and it is based on observations at a later shot in the area of Shot SMOKY.

There is no doubt that at least one of the two platoons encountered unexpected radiological conditions during the period after the assault on Objectives

2A and 2B began. With reference to Figure F.1, Shot SMOKY was detonated in an area of north Yucca Flat that is ringed to the north and west by mesas, as indicated by the dense contour lines to the northwest of the landing areas. The elevation at ground zero is about 1,400 m, and the elevation of the mesas reaches about 2,300 m. The detonation occurred about one-half hour before sunrise. The upper part of the cloud of debris that rose above the elevation of the mesas was carried to the south and southeast by the winds aloft (Hawthorne, 1979), as indicated by the fallout pattern in Figure F.1. However, as the sun rose, it is plausible that warming of the east- and south-facing slopes of the mesas caused an updraft and, therefore, a northwestly wind at low elevations in the area of the maneuvers. As a result, the stem and lower portions of the cloud that had not risen above the mesas and portions of the remaining dust cloud caused by the blast wave could have been transported in the direction of the platoons on Quartzite Ridge and resulted in fallout along the planned path of the assaults.

The scenario described above does not contradict a statement in Appendix F.3 that a dust cloud in the vicinity of the landing areas to the north-northwest of ground zero was soon transported back toward ground zero by a west wind, because the eastward movement of the dust cloud, which could have been caused by reflection of the blast wave from the slopes of the mesas to the west, occurred 3 hours before the assault by the 2nd and 3rd Platoons was halted (Jensen, 1957). Thus, the two occurrences probably are unrelated.

The committee believes that two pieces of evidence support an assumption that the platoons assaulting Quartzite Ridge encountered unexpected fallout that was not lofted above the mesas but was transported to the northwest of ground zero at low elevations. First, such an occurrence after underground Shot BANEBERRY in December 1970 is documented. As shown in Figure F.2, photographs of the plume from Shot BANEBERRY, which vented to the atmosphere about 4 km west of ground zero of Shot SMOKY, clearly indicate movement of the lower portion toward the northwest, with the upper portion drifting north and east under the influence of winds aloft.

Second, ground survey teams that approached ground zero from different radial directions within the first 3 hours after detonation of Shot SMOKY, including a monitor who approached from the southwest, encountered conditions that caused erratic instrument readings and contamination of the instruments (REECO, undated; Harris et al., 1981). Those conditions could have been caused only by airborne radionuclides that were not carried in the rapidly rising fireball but were separated from the fireball, probably by reflection of the blast wave from the slopes of surrounding mesas, including a mesa to the north indicated in Figure F.1. If most of the radionuclides had been carried in the fireball, the extensive fallout encountered by the ground survey team would not have occurred for several hours, given the typical height of a cloud of about 10 km (see Section IV.C.2.1.5) and a typical fall velocity of large fallout particles of about 10 cm s−1

FIGURE F.2 Photograph of plume from underground Shot BANEBERRY showing separation of lower and upper portions due to different directions of winds near the ground and aloft.

(Sehmel, 1984). That assertion is supported by a report that stable measurements by the survey team were possible by 0900 hours, or about 4 hours after detonation (Harris et al., 1981). Airborne radionuclides at low elevations that were separated from the fireball were available for transport to the northwest toward Quartzite Ridge as an updraft at the slopes of mesas farther to the northwest occurred.

Thus, the committee believes that the most likely scenario for exposure of at least one of the platoons on Quartzite Ridge is that airborne radionuclides that were separated from the rapidly rising fireball were transported from the area around ground zero by surface winds generated by an updraft at the slopes of mesas to the north and west of Quartzite Ridge as the slopes were heated by the morning sun. The credibility of that scenario is supported by a similar occurrence at underground Shot BANEBERRY near ground zero of Shot SMOKY and by the evident presence of substantial amounts of airborne radionuclides at low elevations in the vicinity of ground zero for more than 3 hours after detonation. In the scenario, the unexpected radiological conditions experienced by at least one of the platoons presumably were due to fallout at planned locations of the assaults on Objectives 2A and 2B.

F.7 EVALUATION OF APPROACH TO DOSE RECONSTRUCTION

The committee’s primary concern about the unit dose reconstruction for Task Force WARRIOR (Goetz et al., 1979) involves the assumed exposure scenario for the two platoons that assaulted Quartzite Ridge and encountered unexpected radiological conditions that resulted in premature termination of the exercise. It is the committee’s opinion that by forcing the scenario to be consistent with the expected radiation environment, the analysts developed a scenario that required implausible and unsupported assumptions about the actions of one of the platoons and thus lacked credibility. The analysts apparently assumed that available survey data after Shot SMOKY defined the radiation environment in areas near Quartzite Ridge during the assault and thus precluded high radiation levels at those locations and times. However, radiation levels were not measured near Quartzite Ridge to support the assumed scenario (REECO, undated). Rather, radiation levels to the northwest of ground zero were simply assumed on the basis of an extrapolation of measurements elsewhere and the belief that the entire plume traveled south and east away from Quartzite Ridge. The committee believes that there is a plausible scenario that is consistent with all available information and would explain the unexpected radiological conditions encountered during the assaults on Quartzite Ridge, without the need to invoke an assumption that one of the platoons inadvertently or deliberately disobeyed orders and marched a considerable distance in a different direction and into a high-radiation area near ground zero.

The committee’s concern about the exposure scenario assumed by Goetz et al. (1979) goes beyond the reconstruction of external dose for Task Force WARRIOR. An assumption of an implausible scenario does not have important consequences for estimating external doses to members of the platoons on Quartzite Ridge, because doses could be estimated from film-badge readings. Rather, the implausible scenario is important, in part, because it ignores possible doses due to inhalation of descending fallout, which probably contained important longer-lived radionuclides that were deposited in the area after previous shots and were resuspended by the Shot SMOKY blast wave.

Of greater concern to the committee is that the assumption of an implausible exposure scenario in this case is not an isolated occurrence. In its review of 99 randomly selected individual dose reconstructions, as discussed in Section V.A, the committee encountered several cases in which an analyst developed an exposure scenario based on prior expectations of exposure conditions or a scenario that conformed to a plan of operation or operational radiation protection guidelines but in doing so ignored evidence, including statements by participants, that indicated that the actual conditions of exposure did not conform to the assumptions. Plausible scenarios that could have resulted in substantially higher doses than were obtained in a dose reconstruction were not considered. Indeed, in contrast to the unit dose reconstruction for Task Force WARRIOR, in which the

analysts assumed that troops must have disobeyed orders to receive external doses indicated by film-badge readings, analysts have argued in other dose reconstructions that a plausible scenario could not have occurred because it was against orders, did not conform to a plan of operation, or resulted in doses exceeding operational guidelines (see case #3, 58, 77, and 92).

The committee believes that development of exposure scenarios for use in dose reconstructions for atomic veterans should not be dictated by plans of operation. Rather, plausible alternatives involving unexpected occurrences should be considered and evaluated when they are supported by available information, as is sometimes the case. The goal should be to develop plausible scenarios that are consistent with the body of available information and result in the highest estimates of dose to give veterans the benefit of the doubt as required by regulations governing the NTPR program.

REFERENCES IN APPENDIX F

Goetz, J. L., Kaul, D., Klemm, J., McGahan, J. T. 1979. Analysis of Radiation Exposure for Task Force WARRIOR—Shot SMOKY—Exercise Desert Rock VII-VIII, Operation PLUMBBOB. McLean, VA: Science Applications, Inc.; Report DNA 4747F.

Harris, P. S., Lowery, C., Nelson, A. G., Obermiller, S., Ozeroff, W. J., Weary, E. 1981. Shot SMOKY, a Test of the PLUMBBOB Series, 31 August 1957. Alexandria, VA: JAYCOR; Report DNA 6004F.

Hawthorne, H. A. (Ed). 1979. Compilation of Local Fallout Data from Test Detonations 1945–1962 Extracted from DASA 1251. Volume I. Continental U.S. Tests. Santa Barbara, CA: General Electric Company; Report DNA 1251-1-FX.

Jensen, W. A. 1957. Report of Test, Infantry Troop Test, Exercise Desert Rock VII and VIII. San Francisco, CA: Headquarters, Sixth US Army; Report AMCDR-S-3 (December 11).

REECO (Reynolds Electrical & Engineering Company, Inc.). Undated. PLUMBBOB On-Site Rad-Safety Report. Las Vegas, NV: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission; Report OTO-57-2.

Sehmel, G. A. 1984. Deposition and Resuspension. In: Atmospheric Science and Power Production, ed. by D. Randerson. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy; Report DOE/TIC-27601, pp. 533–583.