8

Personnel Qualifications, Training, and Continuing Education

INTRODUCTION

Research, educational, and testing facilities that use nonhuman primates are usually dynamic environments. Changes in these environments require a commitment to training and continuing education to provide a safe and healthful workplace. Some changes involve staff turnover and the involvement of new students and visitors at a facility. New animals and even new nonhuman-primate species are received and new studies begin with their own procedures and equipment. Other changes are facility-related, such as those caused by facility modification (addition or reconfiguration). Changes in equipment can include new caging and housing systems, new materials-handling equipment, new anesthetic or surgical equipment, and the use of new instruments and devices. Training and continuing education programs provide an opportunity for management and staff to communicate about workplace hazards, program changes, updated organizational policies and procedures, and emergency procedures.

An institution can achieve its OHS objectives only if its employees know the hazards associated with their work; understand how the hazards are controlled through institutional policies, engineering controls, work practices, and PPE; and have sufficient skills to do their work safely and proficiently (NRC 1997). To meet those requirements, a multifaceted training program that addresses the full array of health and safety issues related to the care and use of nonhuman primates must be instituted.

Such a program not only benefits the workers, it also benefits the institution through minimization of occupational illness and injury and lost time.

Institutions have legal and ethical responsibilities to provide staff with the training, knowledge, and equipment they need to protect themselves from workplace hazards. In 1985, Congress enacted two laws that require that institutions provide training for staff who care for or use animals: the Health Research Extension Act (Public Law 99-158), which made compliance with the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy a matter of law for all PHS-funded research, and the Food Security Act (Public Law 99-198), which amended the Animal Welfare Act (7 USC 2131-2156).

This chapter provides a framework for assessing personnel qualifications and developing training and education programs for organizations that use nonhuman primates in research, education, and testing.

PERSONNEL QUALIFICATIONS

AAALAC International requires accredited institutions to describe personnel qualifications in the accreditation application; OLAW lists evaluation of personnel qualifications as an IACUC oversight responsibility.

The point of responsibility for assurance of personnel qualifications must be clear if conformance with AAALAC International and federal guidelines are to be met. Nonhuman-primate housing facilities are often centralized and used by research staff from an entire institution. If personnel that work with the nonhuman primates do not share local lines of authority, it can lead to confusion about responsibility for qualification assurance. The facility director is ultimately responsible for determining the qualifications of facility employees, contract staff, support-services staff, program inspectors, and visitors who work with or around nonhuman primates and the associated equipment. Principal investigators are responsible for the verification of the qualifications of research assistants, collaborators, and guests.

Delineation of responsibility for assurance of qualifications should be established by institutional policy. Such policy demonstrates that upper management recognizes the importance of personnel qualifications, has determined an appropriate assurance plan, and has delineated responsibility for the implementation of the plan.

Management should determine operationally specific minimal qualifications for all staff and visitors that work directly with the nonhuman primates, their byproducts, housing, holding rooms, equipment, or tissues. Minimal assurance of qualification is important not only for new employees but also for current staff as they gain proficiency and engage

in more challenging tasks. Attention should also be given to the development of qualification standards for support staff, such as maintenance personnel, housekeeping staff, materials-handling staff, providers of such services as pest management, laundry, environmental monitoring, and occupational medicine, and emergency personnel such as police and firefighters. Conducting a facility orientation and an overview of the operationally specific hazards, risks, policies, and emergency procedures for support staff is recommended.

Managers, principal investigators, and others often view possession of pertinent professional credentials, a history of work with nonhuman primates, or simply length of employment as evidence of qualifications. This can be a dangerous assumption. All personnel who work in nonhuman-primate facilities and everyone who works with nonhuman-primate tissues must have knowledge of task-specific hazards, be able to recognize when an exposure has occurred, and be able to accurately demonstrate emergency steps to take in the event of an exposure.

An assessment of basic skills is often a good place to start in assessing a person’s qualifications. Through observation, supervisors can note whether an employee has the basic communication skills necessary to perform the task at hand and whether the employee’s reading skills are sufficient for understanding the SOP, organizational policies, and material-safety data sheets applicable to their position. After establishing a person’s basic skills, management can strengthen assurance of qualifications by conducting behavioral observations and comparing them with the previously established minimal qualifications. Supervisors can observe new and current employees engaged in tasks and note their familiarity with the nonhuman-primate species used, equipment, and tasks. Through behavioral observations, a supervisor will be able to observe an employee demonstrating (or failing to demonstrate) the knowledge, skill, and deportment needed to conduct specific tasks safely.

It is important to assess behavior in a task-specific context. To determine whether a person is qualified to perform a specific task involving a nonhuman primate or nonhuman-primate tissues, the supervisor may choose to seek answers to several pertinent questions, such as the following:

-

Has the person performed this task before?

-

If so, how long has it been since the person last performed the task? Has anything about the task changed since the person last performed it?

-

Was previous performance of the task of a similar duration?

-

Has the person worked with the necessary equipment before?

-

Is the person familiar with the equipment’s uses and associated risks?

-

Has the person performed this task with others or independently?

-

How confident is the person of his or her ability to conduct the task safely?

-

Has the person been observed and found to be proficient in the performance of the task?

-

Has the person worked with this species of nonhuman primate before?

-

Is the person not only familiar, but also experienced, with the species-specific behaviors, housing, handling, and restraint methods?

-

If the animal being manipulated is to be anesthetized, does the person show proficiency in the use and administration of anesthesia?

It is clear that a qualification assessment can benefit enormously both from the exchange of information between management and staff and from observation. Thoughtfully constructed dialogue can help to identify skill or knowledge deficiencies and pinpoint the need for initial and refresher training. Supervisors should always verify the written and stated qualifications of an individual employee with observation. This measure will help to ensure that the knowledge and skills that a person claims to have are commensurate with the specific task requirements and safe work practices.

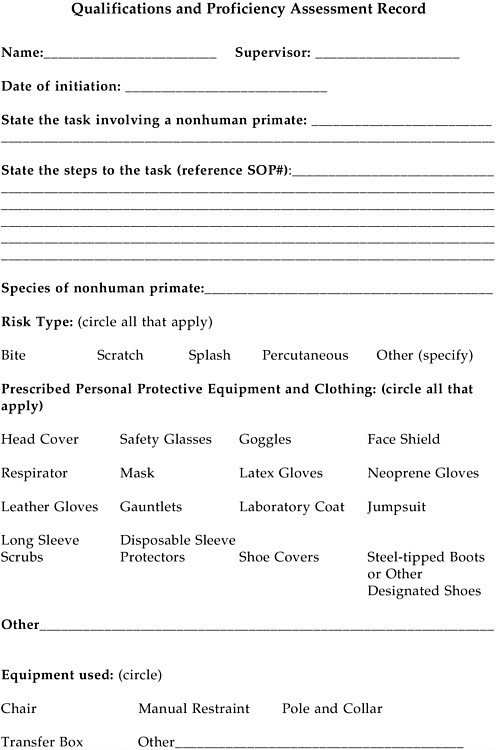

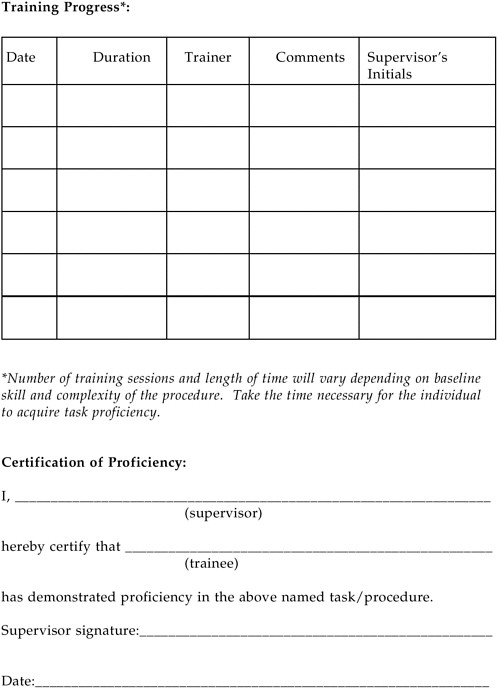

There are many approaches to determining whether a person is qualified to perform a specific task. One approach is the use of proficiency assessment documentation. The following form is an example of how an institution can document an individual’s qualifications and proficiency for a specific task. This sample form is aimed at a task or procedure involving awake nonhuman primates, such as a pole and collar transfer or transfer of the animal to a clean cage. The form can be easily modified to accommodate additional tasks, such as cagewashing, material handling, environmental enrichment, and tasks involving anesthetized nonhuman primates.

TRAINING

The ultimate goal of safety training is to reduce occupational exposures, accidents, near-accident incidents, injuries, and illnesses (Gershon and Zirkin 1995), that is, to ensure that safety-related human performance and training discrepancies are identified and that appropriate techniques are used to improve the safety and health of the workforce. The program will do this by providing information to improve knowledge, demonstrating safe work techniques, providing instruction on emergency response, providing information on regulatory controls, providing infor

mation and yearly updates on safety policies and procedures, and motivating staff to work safely (Gershon and Zirkin 1995).

Requirements established by federal and state regulations, accrediting, and funding agencies place various training demands on institutions where nonhuman primates are housed and used, and training records should be maintained and retained in accordance with applicable federal and state regulations and guidelines. Thoughtfully constructed and conducted staff training can have a major impact on the safety record of the institution.

An effective training program requires resources, administrative support, recordkeeping, and a system for monitoring training efficacy. Management can demonstrate its commitment to its safety and health training program by funding it appropriately and by visibly supporting the program, its goals, and its objectives.

Safety training should begin at each new employee’s orientation and progress continuously as more complex tasks are assigned and job responsibilities increase. Staff may perform a variety of tasks, from routine daily care and feeding of animals to animal handling and research-associated manipulations; the multifunctional aspect of the work can mean that the skills personnel must have will vary greatly in regard to complexity. Periodic refresher training is needed to maintain proficiency and adherence to institutional procedural standards. Safety training should also be conducted when unsafe or risky behavior is observed.

To be successful, safety training should be delivered routinely. When safety training is provided only episodically, such as when an accident has occurred, it can be interpreted by staff as punitive and have an undermining effect on accident-reporting compliance. Safety training should be conducted during regular work hours; this demonstrates that management values the training and recognizes it as an integral part of employment. Training topics should be chosen carefully to meet real training needs. Training should be developed for individuals and for specific worker groups, and that training should be delivered in terms related to the specific environment and at a trainee-appropriate cognitive level. If possible, trainers should be selected from current staff to ensure the program specificity of the training and to facilitate follow-up discussion after the training. Two-way communication is important in a training program; staff must be afforded the opportunity to ask questions and clarify their understanding of the messages being presented.

Several key factors can improve the effectiveness of training:

-

The trainer must be knowledgeable and an effective communicator.

-

The message to be conveyed should be succinct and not cover too many topics at once.

-

The audience must comprehend the message; training should be aimed at the proper level of knowledge and understanding (including language).

-

The environment in which training is conducted should be conducive to the lesson at hand, lighting, temperature, no distractions, and so on (Gershon and Zirkin 1995).

Many OHS professionals have found value in an annual training plan. Upper management, organizational safety committees, supervisors, workers, and safety managers should provide input pertinent to a comprehensive and operationally specific annual training plan. The plan should outline training-specific details, such as training topics, dates and duration of training sessions, needed resources, and training objectives. A training plan communicated well ahead of time to managers and administrators has several benefits; it will minimize organizational disruptions by allowing management to plan around presentations and it provides administrators with information needed for resource allocation and management decisions.

Several methods are available to assist managers and supervisors in their approaches to training. The following elements will help to ensure that the instructional program will be effective and meet the needs of both the organization and individual personnel: needs assessment, development of objectives, determination of content, selection of methods and techniques, establishment of the timing and administration of training, and evaluation are all important (Broadwell 1986). These elements are discussed below.

Periodic Needs Assessment

Training needs should be assessed in regard to organizational needs, worker group needs, and individual worker needs. Organizational needs are based on organizational goals and objectives. Worker group needs can be described as departmental or unit needs, such as the needs of a research group or the needs of those involved with routine husbandry procedures, including care and feeding. Examples would be group skills training or familiarization with required procedures for a new study and training in the use of a new piece of equipment. Individual employee needs can be as varied as basic literacy and numerical skills, special technical skills, new-employee orientation, and task-specific employee competence. In many occupations, the confidence that an employee has in his

or her own ability can directly influence on-the-job safety. Managers and supervisors should listen to staff, observe them, and be responsive when employees demonstrate or otherwise convey their lack of confidence in performing a particular task.

Before launching into training as a solution, it is important to determine whether training is likely to solve a problem or resolve an issue; training is not the answer for all situations. There is often a difference between what people are expected to do and what they are actually doing, and training might not be effective in resolving the disparity. For example, a manager might observe an increase in the number of occupational injuries associated with the movement of nonhuman-primate caging. If investigation reveals that employees are not using a mechanical lift to move large objects, such as macaque caging, and thus are not following SOP, management needs to look into why the staff are not using the lift. Talking with staff directly can often reveal why they are performing outside operational standards. In the example, such discussion could include the following questions:

-

Is the lift operational?

-

Is the lift the right piece of equipment to do the job?

-

Are there enough lifts available to meet the unit needs?

-

Does corridor activity permit the safe passage of a mechanical lift?

-

Do the employees know how to operate the lift correctly?

Such questions will help supervisors and managers to determine whether training is warranted. Perhaps the real reason for not using the lift is simply that at peak use times there are not enough lifts to meet staff needs. Intervention might include the purchase of enough lifts to meet staff needs, rather than lift-operation training.

Work analysis, job and task inventory, assessments, and surveys or questionnaires can be useful for pinpointing training needs. A work analysis is accomplished by breaking down a job into the required skills and knowledge. Similarly, a job or task inventory involves breaking down a job and ranking tasks by whether lack of pertinent knowledge or skill can have serious consequences. Assessments or surveys can be conducted by written or oral methods and can reveal training needs through identification of discrepancies between employee replies and the responses desired by management. Surveys can be conducted anonymously to give a trainer a feel for group beliefs, knowledge, or perceptions of risk, or on an individual basis to provide a trainer with individual specific training needs.

A needs assessment will identify discrepancies between what people

are doing, how they are doing it, and the prescribed way to do it safely. A needs assessment should involve an overall evaluation of an organization’s program, processes, and past performance. It is most helpful to assemble an interdisciplinary group of people to conduct the assessment or to seek their individual inputs. The functional parts of the overall program should be examined initially followed by the processes or activities that define them. In a research facility that houses nonhuman primates, the functional parts might be animal care and feeding, enrichment, animal health, and technical assistance. Activities associated with animal care and feeding would include cagewashing, animal transfer, material handling (caging, feed, and bedding), and daily animal room maintenance. A review of past performance is one way to evaluate a quality assurance program and is also fundamental to a complete needs assessment: injury and illness reports, absentee and out-sick records, safety and health citations, and staff and management views about worker safety and health concerns. This review can be inserted into the quality assurance program.

Development of Objectives

Training objectives should clearly reflect the desired training outcome. There are programmatic objectives and learning objectives. Both should be identified in the training plan. The programmatic objectives should be written to meet organizational goals, for example, to reduce accidents by 10% on an annual basis. Learning objectives should state what is expected of the trainee. Properly written learning objectives have three basic elements: the task to be completed, the conditions under which the task is to be completed, and the behavior or performance that is being measured and the standard against which it will be measured (Broadwell 1986). These three elements may be expressed as performance, condition, and criteria (Mager 1997). The objectives must be specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and trackable (Broadwell 1986). The following are examples of learning objectives:

-

The trainee will demonstrate how to perform an eyewash at the unit’s eyewash station.

-

The trainee will be able to quickly list three areas of the face that are recognized as sites of a mucosal exposure to potentially infectious splashes.

-

The trainee will be able to quickly state the steps to take after a percutaneous exposure to material potentially contaminated with B virus.

-

The trainee will be able to state one aggressive macaque behavior and one nonaggressive macaque behavior as taught in class.

Determination of Content

Training content should reflect primarily what the trainee must know as opposed to what the trainee should know or could know (Broadwell 1986). To enhance comprehension and retention of training material, the number of major concepts in any training session should be limited to seven, with each major concept being presented at least three times during the session. Trainees should be told at the outset of training what will be presented, why it is important, and how they should use it in their daily work activities. That information will convey the relevance of the training at the beginning of the session and prepare the learner.

The involvement of scientists in the development of content for health and safety training is particularly important. Often, employees who routinely care for nonhuman primates are not placed under the direct supervision of the scientist who is responsible for the research project, so there can be gaps in communication of information that is necessary to protect worker health and safety or information that could correct misperceptions about risks associated with the project. Such gaps could also place the research animals at unnecessary risk if exposed to a staff member who is an active carrier of an infectious agent. Safety-related information from the scientists needs to be conveyed both to the animal care staff and to their supervisors. Supervisors who understand the research objectives and the attendant hazards will create and maintain a safe work environment in which the animal care staff can be integral and knowledgeable participants in the research activity (NRC 1997).

The following are examples of the types of topics and content that may be presented in safety training:

-

Facility orientation. Entrance requirements, facility policies, emergency procedures, and management overview.

-

Overview of the organization’s safety program. Integration of safety into SOP, the safety committee, safety elements of performance appraisals and position descriptions, and overview of the safety department and the organization’s safety policies.

-

Hazards. Hazards unique to nonhuman primates and the institution’s specific activities.

-

Personal protective equipment. Type required, function, protective capability, selection, individual fit, cleaning, storage, and replacement.

-

Personal protective clothing. Function, protective capability, proper donning, wearing and removal, care, cleaning, and storage or disposal.

-

Eye protection. Selection, individual variability, fit, task-specific selection, coverage, and care and storage.

-

First aid. An overview of first aid to be administered in the event of an exposure.

-

Material safety data sheets. What they are, how to use them, where they are stored, and limitations.

-

SOP. What they are, how to use them, where they are stored, and limitations.

-

Species-specific behavior. Threat behaviors, affiliative behaviors, individual differences, and descriptions of how the species responds to human behavior.

-

Sharps safety. Proper selection, use, and disposal; proper use of safe sharp devices; and when to use these devices.

-

Protection of the back. Proper lifting techniques and alternatives to lifting.

-

Safe movement of equipment. Overview of equipment-related accidents and injuries, safe hand placement, hand protection, and overview of instances when more than one person may be needed to move a piece of equipment and why.

Selecting Methods and Techniques

Once the needs assessment has been done, the learning objectives developed, and the training content determined, training methods and techniques to accomplish the stated learning objectives can be selected. Types of training methods and techniques include traditional classroom style, on-the-job-training, practical hands-on training for groups and individuals, and computer-based training. For substantial learning to occur, learners must be actively involved in the learning process (Bird and Germain 1996). If the training pertains to humane restraint of an alert adult macaque, it may entail multiple methods, such as classroom instruction, practical exercise of restraint technique with a macaque model, and individual instruction with an animal.

Timing and Duration of Training

The time needed for instruction is based largely on the training objectives established and the content of the training. The more complex the issue, the more time may be required for training and learning. Generally speaking, more time should be allowed when conveying new information during training than for a refresher session or for teaching a variation of an existing operating standard.

Administration of Training

Trainees want to know why the information conveyed during training is important to them and their organization. They want to know how management expects them to use the new information. They want the training session to be organized and concise. And, they want to be treated with respect.

Five basic principles of adult learning have been identified (Bird and Germain 1996):

-

Principle of Readiness. We learn best when we are ready to learn. You cannot teach someone something for which he or she does not have the necessary background of knowledge, maturity, or experience. Readiness also means that the learner is emotionally ready and motivated to learn; this readiness is created by communicating to the trainees why the training is important and how it will be of benefit to them (for example, in career progression, improved performance evaluations, and safer work).

-

Principle of Association. It is easier to learn something new if it is built on something we already know. Start with the known practices and proceed to the new. Build up to the new information or more difficult tasks from the base of the known and familiar ones.

-

Principle of Involvement. Substantial learning will occur when learners are actively involved in the learning process. The more senses involved (hearing, seeing, tasting, smelling, and feeling), the more effective the learning. Learner-involvement tools include practical or hands-on training, questioning of the group, open discussion, case studies and problem-solving, simulations, and demonstrations.

-

Principle of Repetition. Repetition aids learning, retention, and recall. When there is a long period of disuse of information after it is learned, learned responses can weaken.

-

Principle of Reinforcement. The more likely a response is to lead to satisfaction, the more likely it is to be learned and repeated. Instructors should use praise, reward, and recognition to reinforce learning.

Evaluating the Training

Learning is measured by a change in behavior. For example, are the trainees from the back-safety class demonstrating proper lifting techniques as demonstrated in class? Supervisors and managers must be knowledgeable about the content of training programs so that they can effectively monitor workplace practices and behavior to ensure adherence to prescribed methods or investigate and mitigate the reasons for discrepancies.

Several approaches can be used for evaluating the success of the training program. Periodic evaluation of the presentation, instructor, accommodations, and resources can assist in training program revision and improvement. That can be accomplished through student evaluation forms and monitoring of the training process by management and supervisors. Pre- and post-training testing can provide an indication of the information learned, how it is used, and changes in risk perception and attitudes. Other training-evaluation mechanisms include site inspection, personnel review, review of injury and illness records, review of regulatory-compliance citations, and periodic use of questionnaires. The approach should be carefully designed and applied to provide information useful for both institution officials and employees (NRC 1997).

One measure of training effectiveness is organizational impact. Has the organization experienced reduced costs associated with injuries since training inception? Perhaps there has been observable improvement in work quality or quantity. Improvements in worker-management relations can be effected through safety training. Safety should be integrated into the organization both horizontally and vertically, and safety-training efforts should be followed by careful review of activities and findings to develop recommendations for overall program improvement.

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Continuing education provides a broad background in which much of the information presented might not be directly related to the trainees’ experience and needs. Training is job- and task-specific; training is directly related to performance and is intended to improve performance (Broadwell 1986). A qualifications assessment and a periodic individual needs assessment will assist those responsible for training to determine when continuing education, as opposed to training, is warranted. Does the person have an educational base that, when supplemented with the training that the institution is prepared to offer, will make it likely that the person will be qualified for a particular job? If the answer is no, continuing education is probably warranted. The resources required for offering continuing education are often different from those required for training, because of the broad background of the information to be presented. Institutions that use nonhuman primates for research, education, and testing often sponsor continuing education for assistant-technician, technician, and technologist certification examinations, and support veterinarians’ preparation for board certification.

RECORDKEEPING

Recordkeeping is an essential aspect of a training program. Training records should reflect the date of the training, the instructor’s name, names of attendees (documented with their initials), the location of the training, duration of training, broad topics, subtopics, learning objectives, course content, and a list of handout materials. Organizations such as AAALAC International and IACUCs may request review of training records during site visits and inspections. Some training records are required to be retained for specified durations to satisfy federal and state environmental health and safety regulations. Animals experimentally infected with HIV or HBV are included under the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030) in the category of “other potentially infectious materials.” For training that is conducted to satisfy compliance with this standard, OSHA requires training records to be retained for 3 years. State OHS offices and regional OSHA representatives have information on specific requirements that may affect a facility. The institutional official is responsible for ensuring the maintenance of training records.

The head of the environmental health and safety office will usually strive to establish a simple system that presents the smallest administrative burden. A computer-based system should facilitate such an approach (NRC 1997).