3

Improving the Effectiveness of NGDC

This chapter reviews the four tasks that relate toimproving theeffectiveness of the National Geophysical Data Center (NGDC).

Task 5. How well does NGDC collect the data and information it needs to effectively conduct its activities?

Task 6. How effectively does NGDC measure customer satisfaction?

Task 2. Is NGDC organized, staffed, equipped, and supported to fulfill its mission?

Task 4. Are NGDC’s performance measures appropriate for tracking progress in achieving results and for judging center funding?

DATA AND INFORMATION COLLECTION

One of NGDC’s missions is to acquire solid earth, marine geophysical, ionospheric, solar, and other space environment data. Examination of the holdings shows that data collection is rarely comprehensive and is even spotty in some cases. Examples of “missing” data include bathymetry data collected by individual investigators, marine seismic data collected by organizations around the world, historical ocean-bottom photography data, and popular geomagnetic indexes. Reasons why the data may be incomplete include:

-

NGDC is one of many archives in marine geology and geophysics, solid earth geophysics, and solar-terrestrial physics.

-

NGDC staff members are given great latitude in what data to acquire, and they are most likely to seek data with which they are familiar.

-

Funding limitations require the center to be opportunistic about what data are acquired or rescued (i.e., mission relevance and available funding appear to be the primary criteria for acquiring data; see Box 2.1).

-

Principal investigator requirements to deposit data in some disciplines are commonly not enforced by funding agencies (e.g., National Science Foundation [NSF], National Aeronautics and Space Administration [NASA], Department of Defense). As a result many important research programs do not contribute data regularly to NGDC.

NGDC has established a number of effective partnerships for acquiring data from other parts of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The fact that the center is taking on more responsibility for archiving and distributing gravity and geodetic data, for example, attests to its ability to perform these functions well. However, NGDC has not had equal success with the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS) or with data collection programs outside NOAA. For instance, NESDIS has not assigned responsibility for the National Polar-Orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS) space environment dataset to NGDC, even though staff expertise in developing and distributing such products would ensure better continuity between the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program and NPOESS products, enabling them to be used for studies spanning the two satellite eras. Moreover, some communities are considering whether to archive all their data at NGDC. For example, a recent workshop sponsored by the NSF and the Office of Naval Research recommended the establishment of a distributed system of discipline-specific archives, rather than a central repository for marine geology and geophysics data.1 NGDC will have to convince organizations that hold relevant data that they are best handled by NGDC and should eventually be archived at the center.

The “national” in NGDC implies that the center is a primary place to find a wide range of geophysical data. To be an effective national center NGDC need not have comprehensive holdings, but it should provide comprehensive access to geophysical data on its Web site by pointing to organizations that hold complementary data. Such organizations include the seismic reflection archive at the University of Texas; GLORIA sidescan sonar images and interpretive geographic information system layers at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS); offshore seismic data at the Minerals Manage-

ment Service; seismic data from the Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS) Data Management Center, USGS, Southern California Earthquake Center, International Seismological Centre, and the University of California, Berkeley; geodetic data from the UNAVCO Facility; elevation and land cover data from the EROS Data Center; geomagnetic data from the Canadian Auroral Network for the OPEN Program Unified Study (Canopus) at the Canadian Space Agency; magnetograms from the International Monitor for Auroral Geomagnetic Effects (IMAGE) program in northern Europe and Russia; ground-based magnetic records curated by the space physics group at the University of California, Los Angeles; magnetometer data from Magnetometer Array for Cusp and Cleft Studies (MACCS) at Boston University and Augsburg College; and geomagnetic data from the Polar Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (POGO) and Magsat at NASA, from the Orsted satellite at the Danish Meteorological Institute, and from the Gravity and Magnetic Field Mission (CHAMP) at GeoForschungsZentrum.2 None of these are prominently found on NGDC’s Web site or are simply listed without explanation under “related web sites.”3 Yet such pointers are a valuable service to users, especially those conducting studies that require data from multiple sources (e.g., see Figure 3.1). Negotiating reciprocal courtesy pointers with other relevant archives would greatly benefit the geophysical and environmental science community.

In the committee’s view NGDC should be an authority that is knowledgeable about the existence of all significant geophysical and complementary data relevant to its mission. NGDC should thus (1) acquire relevant data and metadata for its own databases and (2) provide information on these holdings on the NGDC Web site and links to the data and metadata either at NGDC or the other organization’s Web site.

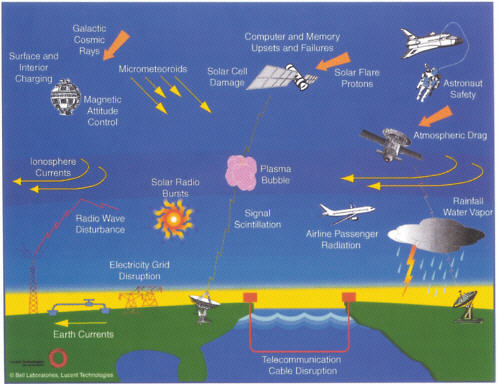

FIGURE 3.1 Some of the effects of space weather on technical systems deployed on and above the Earth’s surface and on signal propagation. Space weather refers to conditions on the Sun and in the solar wind, magnetosphere, ionosphere, and upper atmosphere that influence the performance and reliability of technological systems in space and on the ground or endanger human health. Adverse conditions in the space environment can disrupt satellite operations, interrupt various communication channels, degrade navigation capabilities, lead to the rerouting of transpolar flights, and cause the shutdown of electric power distribution grids. Research in this area is coordinated by the National Space Weather Program and is sponsored by a number of federal agencies, including NSF, NOAA, U.S. Air Force, NASA, USGS, Coast Guard, Navy, Army, Federal Aviation Administration, and the Department of Energy. The principal space weather forecast group is NOAA’s Space Environment Center in Boulder, Colorado. The principal archive of space weather records is maintained by NGDC. SOURCE: L. Lanzerotti, 2001, Space weather effects on technologies, in Space Weather, Geophysical Monograph 125, American Geophysical Union, Washington D.C., pp. 11-22. Reproduced by permission of American Geophysical Union.

Recommendation: NGDC should work with organizations that are sponsoring relevant data collection projects (e.g., National Ocean Partnership Program, National Science Foundation) from the outset to ensure that NGDC will receive the resulting data. It should also provide prominent links on its Web site to complementary archives.

To be most useful, Web links to other organizations should be organized and/or described in a way that helps users navigate through the maze of relevant resources.

CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

NGDC received a Department of Commerce customer service award in 1997 for its work in data distribution, archive and collection, and its focus on customer satisfaction.4 However, the question of whether NGDC’s users are satisfied cannot be answered with available data. The large and growing population of users, which far exceeds the number of scientists and operational users for which the system was designed,5 suggests that many users are getting what they need from NGDC. On the other hand, anecdotal evidence suggests that at least some users visit the center but never return.

Measuring Customer Satisfaction

To assess customer satisfaction it is first necessary to determine who the users are. A detailed knowledge of its user profile is one of the most difficult challenges faced by any data center. In general, data centers track data requests and supplement that information with user surveys, direct feedback from users and visiting scientists, phone contacts, and interactions with their advisory committee to learn about their users’ preferences and satisfaction with the center. However, several of these avenues are not available to or have not been fully utilized by NGDC.

-

With the shift to online access the center is losing direct contact with its users. Before the advent of the Internet the normal procedure for obtaining

|

4 |

Department of Commerce Excellence in Customer Service Award, National Geophysical Data Center, 1997. |

|

5 |

The membership of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) may serve as a proxy for the size of the geophysics community. AGU members represent the fields of atmospheric, hydrologic, ocean, planetary, and solid earth sciences; biogeosciences; geodesy; geomagnetism and paleomagnetism; and space physics and aeronomy. In 2002 there were 38,000 members from 117 countries. See <http://www.agu.org>. |

-

data from NGDC generally involved telephone calls, letters, or even personal visits. With Web-based data distribution, users have become anonymous. NGDC staff no longer know who most of their users are, what they need, or if they are satisfied with the data products. Online users are categorized by domain name, but such categories are misleading, as NGDC recognizes. A scientist working from home may have a dot-com e-mail address, and it is impossible to differentiate user groups from foreign countries or from U.S. e-mail addresses with dot-org, dot-net, or dot-com extensions. Even the number of online users is difficult to determine. NGDC counts hits (a browser request for any one item, such as a page or graphical image), which are likely to be several orders of magnitude greater than the actual number of users.6 It also tracks distinct hosts by Internet Protocol (IP) address for the center as a whole. This measure overestimates the number of users, because the same user may access the Web site from several different computers (e.g., home and work), but it provides the best estimate of unique users with currently available software. Finally, NGDC does not have a means of distinguishing actual users from casual browsers of its Web site. Actual users could be differentiated from casual browsers by tracking the volume of scientifically useful information actually transferred to users from the Web site.

-

The Web site is not used to follow user patterns. Through creative Web page design, NGDC can learn more about the interests of its users, even if it cannot obtain detailed information about who the users are.7 By following the steps of users on the Web site it is at least possible to find out what parts of the system are most used. Which pages were viewed, the order in which they were viewed, and the average number of visits by distinct users can be monitored with any number of sophisticated log-file analyzer programs available at little or no cost.

-

The Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) of 1995 makes it difficult for the center to survey its users. Before the PRA (Box 3.1) was implemented NGDC conducted quarterly surveys of users who received products shipped by NGDC (e.g., posters, CD-ROMs). An analysis of NGDC’s quarterly surveys from 1994 to 19998 shows that these users were overwhelmingly

|

6 |

D. Lohrmann, 2002, Is your site effective? The right metrics can tell, Government Computer News, 21, May 6, <http://www.gcn.com/21_10/tech-report/18546-1.html>. At the IRIS Data Management Center the number of hits exceeds the number of pages viewed by a factor of 8 and exceeds the number of visits by a factor of 25. |

|

7 |

D. Lohrmann, 2002, Is your site effective? The right metrics can tell, Government Computer News, 21, May 6, <http://www.gcn.com/21_10/tech-report/18546-1.html>. |

|

8 |

Respondents were asked to rank the center on a scale of 1 to 6 on the following questions: (1) timeliness of response, (2) condition of package, (3) helpfulness of staff, (4) knowledge of staff, (5) data quality, (6) application to your use, (7) accessibility of data, (8) data format, (9) documentation quality, and (10) data were as described. Users were also invited to provide written comments and suggestions. |

|

BOX 3.1 Paperwork Reduction Act One of the goals of the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995 is to “ensure the greatest possible public benefit from and maximize the utility of information created, collected, maintained, used, shared and disseminated by or for the federal government.” Federal agency responsibilities relating to user surveys are outlined in section 3506. (c) With respect to the collection of information and the control of paperwork, each agency shall— (1) establish a process within the office headed by the official designated under subsection (a),that is sufficiently independent of program responsibility to evaluate fairly whether proposed collections of information should be approved under this chapter, to—

(3) certify (and provide a record supporting such certification, including public comments received by the agency) that each collection of information submitted to the Director for review under section 3507— (A) is necessary for the proper performance of the functions of the agency, including that the information has practical utility; . . . (H) has been developed by an office that has planned and allocated resources for the efficient and effective management and use of the information to be collected, including the processing of the information in a manner which shall enhance, where appropriate, the utility of the information to agencies and the public; (I) uses effective and efficient statistical survey methodology appropriate to the purpose for which the information is to be collected; and . . . (e) With respect to statistical policy and coordination, each agency shall—

SOURCE: Public Law 104-13, See 44 U.S.C. §3507. |

-

positive about the center. On average more than 85 percent of responses were favorable, with the most positive responses concerning the questions “condition of package,” “helpfulness of staff,” and “data were as described.” The most negative responses concerned the questions on data format and documentation quality. Although this information is useful to NGDC, it is important to note that the number of respondents was a tiny fraction of the center’s total users. Respondents declined from about 250 per quarter in 1994 and 1995 to less than 100 per quarter by 1999. In that same interval the number of offline requests dropped from about 25,000 to 10,000 (Figure 2.4b), and the number of online users grew to about 100,000 (Figure 2.4a). By either measure the respondents do not represent a valid statistical sample. And as pointed out above, the respondents were not a representative sample of users because the surveys sampled only offline users who received data.

The Paperwork Reduction Act contains provisions to prevent government agencies from conducting nonrigorous surveys (Box 3.1). Before NGDC can conduct a survey the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) must approve the survey questions and the methodology for analyzing the results. NDGC staff members told the committee that this includes identifying the survey recipients and proving that the survey would yield a 65 to 75 percent response rate. If such a response rate cannot be guaranteed, the center must contract with professional statisticians to develop a statistical analysis plan for dealing with the survey responses. NOAA’s Chief Information Office acknowledges that conducting statistically valid surveys is nontrivial and that OMB approves very few surveys proposed by NOAA. OMB has recently approved a one-time survey of customers who have used data from any of the NESDIS data centers in the past year, although it will only be valid if a 75 percent response rate is achieved.9

The committee feels strongly that user surveys are essential for data centers to gauge user satisfaction with existing products and services and to determine which new products and services are needed. Nonrigorous sur

|

9 |

See <http://www.rdc.noaa.gov/~pra/customer.htm>. The one-time NESDIS survey is posted at <www.ncdc.noaa.gov/survey.html>. Survey questions are similar to but more comprehensive than the questions used by NGDC: (1) quality of service received, (2) quality of product(s) received, (8) timeliness of response, (3) cost of product/service received, (4) degree that product(s) met your needs, (5) format of data received, (6) documentation of data received, (13) description of data in catalogs and directories, (7) accessibility of data, (9) overall satisfaction with service, (10) overall satisfaction compared with services/data obtained from private sector, (11) overall satisfaction compared with services/data obtained from other federal agencies, (12) type of product obtained, (13) primary use of the product(s) received, (14) user affiliation, (15) frequency of product requests, (16) ways in which the data benefited the user or the user’s company, (17) online system used to order data, (18) ease of finding data on the Web site, and (19) data center that shipped the data. |

-

veys yield some information about customers, but the best analysis of customer satisfaction will derive from a properly designed survey with a suitable response rate. The questionnaire being used by NOAA is a reasonable start for learning about users, although additional questions might be useful to better characterize the general public. This survey and the process to obtain OMB approval would be useful guides to other federally supported data centers.

-

NGDC has not had an external committee of users since 1993. External advisory committees provide valuable insight into the needs and satisfaction of different communities with the center.10 The last NGDC external review committee met yearly from 1990 to 1993. In the 10 years that followed, the center has had no formal external advice. The lack of external guidance at the same time that the Web-based system no longer provides user feedback is especially hard to justify. An independent, external advisory committee with rotating membership (1) can provide a fresh view from at least some of the users of the center; (2) could stimulate the center to take useful actions that it might otherwise hesitate to embark on; and (3) can provide input by which NGDC can judge customer satisfaction.

Recommendation: NGDC should take steps to obtain effective feedback from its users by establishing an independent external advisory group, conducting statistically valid user surveys, and making better use of its Web site to characterize users and to define their interests and level of expertise.

Education and Outreach

As noted in Chapter 2 many NGDC users are not scientists in academia or government laboratories, and meeting their needs in practice is given lower priority by NGDC staff. Such an attitude is understandable given funding limitations, NOAA’s apparent user priorities, and the shortage of skills among NGDC staff for serving lay users. According to NGDC’s performance measures, only 0.25 FTE and associated resources must be devoted to outreach (Appendix E). Nonscientists, however, are a growing fraction of NGDC users, and the center will have to devote more attention to this group if it wants them to continue using the center. Currently the center does not make a coordinated effort to educate users about the holdings. For example, at the committee’s site visit one staff member complained about the need to explain basic electromagnetic theory to callers wanting to know how to use their Global Positioning System (GPS) device. The staff member referred callers to the frequently asked questions posted

on Web sites of other entities. Presumably users could then call NGDC back and get more detailed answers to questions that were incompletely addressed on these sites. In the committee’s view education of the user community (including lay users and scientists working outside of their discipline) about matters directly related to NGDC holdings is an issue that should be addressed by the center. However, NGDC’s effort in education and outreach is not substantial, especially compared with the resources devoted by other agencies.11 Education and outreach activities in some federal agencies are becoming more rigorous, and the ad hoc approach of NGDC has not kept up with the times. If NGDC is to meet its stated goal of serving the broader user community,12 it will have to develop a formal education and outreach program, integrated through all the data and information of the center, and spanning the different education levels of the user community.

Recommendation: For NGDC to have an effective education and outreach program, it should first develop a strategy that can be implemented for all disciplines, and the program should be given resources commensurate with that strategy.

ORGANIZATION AND RESOURCES

Intellectual Assets

The Boulder location is an asset to NGDC because of the nearby complementary intellectual and technical capital (e.g., NOAA laboratories, University of Colorado’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Science [CIRES], USGS, National Center for Atmospheric Research [NCAR]). These resources provide a greater pool of scientific expertise than could be garnered by NGDC alone and could be used by the center to better answer questions users have about the data. The CIRES link is used to the

center’s advantage, particularly with regard to technology. However, the committee was surprised to find that links to the academic staff at the University of Colorado are weak, especially compared with the links forged by the National Snow and Ice Data Center.13

Experience based on previous reviews suggests that data centers work best when their staff members understand the data and interact with scientific users. Centers that have robust interaction with the scientific community usually have a high level of customer satisfaction and a highly supportive user advisory committee.14 Metadata, calibration, and data quality all require involvement of the science community. There are several ways to accomplish this. One is to select center staff with scientific qualifications, expertise, and continuing interest in the science. A number of NGDC staff members have scientific credentials and publish regularly. From 1992 to 2002 NGDC staff members authored or coauthored 98 articles in scientific journals and books, conference and workshop proceedings, and organization publications.15 About 75 percent of the publications were peer reviewed. Nearly 40 percent of the staff appear on these publications, with one staff member contributing to one-third of them.

The center could also consider appointing a chief scientist, who would interact with all the divisions to energize the science and lead strategic planning for the scientific activities of the center. The right person—a scientist with a broad range of interests in NGDC disciplines and with an abiding interest in scientific data management and dissemination—would nurture interactions with NGDC’s natural constituency. A chief scientist also tends to attract data from and collaboration with external scientific institutions, which can enhance scientific involvement throughout the center.

Another way to obtain scientific stimulus is to have strong links with the science community. This can be achieved through (1) coauthorship of papers with scientists from outside the center, (2) a scientific advisory

|

BOX 3.2 Halley’s Comet: A Personal Experience with NGDC By Christopher Russell In 1986 when Halley last passed through the inner solar system, I came to realize that earlier in 1910 the geometry of Halley’s passage was such that the Earth passed through Halley’s ion tail. Observers at the time noted this occurrence but were unaware of the existence of the solar wind and the nature of a cometary tail. By the mid-1980s computer simulations had been run using the then understood properties of the solar wind to model the cometary ion and surrounding magnetic tail. We could now interpret ground-based magnetic records that had mystified the observers of 1910. I contacted NGDC and asked if it had records for this period of time. NGDC had ready access to hourly averages recorded as tables of numbers in station logs and requested the original paper records or microfilm recordings of these paper records from various record centers. Eventually sufficient data were acquired for the study to begin. The magnetic records were consistent with the Earth entering a large magnetic tail, surrounding a sheet of flowing heavy ions, and consistent with our modern understanding of the comet. The resulting paper was published, coauthored with two members of the NGDC staff.1 I was very pleased with the interest of the NGDC staff in my problem and the great lengths to which they went to acquire the data. |

committee, and/or (3) a visiting scientist program. NGDC is carrying out the first: About 60 percent of the peer-reviewed papers mentioned above were coauthored by scientists outside the center. Indeed, one of the committee members has published with NGDC staff (see Box 3.2). However, NGDC has no scientific advisory committee and although it has a number of visitors, it has no real visiting scientist program. NGDC’s advisory committee recommended establishing a visiting scientist program in 1990, 1992, and 1993.16 Most of the visiting scientists on the NGDC roster are retired NGDC employees, who are contributing positively to the center. However, to realize the true

benefits of a visiting scientist program the retired staff should be supplemented by routine visits by scientists from outside organizations.

Recommendation: NGDC should improve scientific involvement of center personnel with the datasets by recruiting scientists to work with the data, establishing a vigorous program of external visiting scientists, and/or creating strong partnerships with other agencies, industry, and academia to supplement staff expertise.

Implementing this recommendation would require a culture change and incentives for working with the data.

Staff

NGDC staff is aging and has been dwindling in number for several years, although the number of managers has remained the same. Yet the center has done little recruiting to fill in after retirements or departures and is thus losing the benefit of younger staff with fresh ideas. Not filling vacancies also sends the implicit message that particular tasks are not important. If the center does not replace a departing seismologist, for example, the implication is that one was not needed. Other staff members may wonder if that applies to their tasks as well.

Not filling vacancies also skews the balance of skills, especially since NGDC appears to devote little effort to retraining staff to fill new jobs needed by the center. For example, the committee noted apparent short-ages of skills in the areas of technological support and education and outreach. The senior Oracle database administrator, the network administrator, and Linux/Unix computer systems administrator are drawn from CIRES. CIRES also provides the only staff member with experience in teaching grade school.

Although CIRES positions compensate in part for NGDC’s inability to hire, they are not permanent and CIRES staff members are intended to conduct research, not operations. The upcoming round of retirements provides an unprecedented opportunity for the center to adjust the balance of permanent expertise and inject new blood into the center. The center should plan for this shift in personnel by developing a staffing strategy that outlines the skills needed and how to recruit qualified staff, including external searches to fill critical leadership vacancies.

Recommendation: NGDC should develop a strategy for recruiting and retaining staff that places a high priority on enhancing the scientific vigor of the center and ensures that key technological expertise resides on the permanent staff.

Organization

In the early years of NGDC there were a number of reasons for operating three parallel science elements: (1) scientific expertise in the holdings could be concentrated, making it easier for staff to work on multiple related projects; (2) an additional layer of management facilitated dealing with a large staff; and (3) the techniques for handling data were different in the different disciplines. With the shrinking staff and generalization of data management techniques, an internal organization along disciplinary lines may no longer be justified. Indeed, such a structure has two important disadvantages: (1) many data management functions are duplicated, which is not affordable in an era of flat budgets; (2) the divisions are isolated scientifically and managerially; and (3) the divisions often compete with one another, rather than collaborate. Keeping scientific expertise with the holdings is important for managing data and serving users well, but walling off the component disciplines inhibits cross-fertilization within NGDC, as well with other centers. A recent example is the transfer of the paleoclimate division to another NOAA data center, which was facilitated by its separation from the other NGDC divisions.

Organizing NGDC so that a common set of services and functions serves all disciplines would reduce duplication of effort. NGDC already has an information services division that handles systems administration and computer maintenance for the entire center. Other crosscutting services and functions include software engineering, relational database management, geographic information systems, and documentation and publication. On the other hand, maintaining expertise in the data is a service that probably cannot be shared across the disciplines. Whatever organizational structure NGDC adopts has to be flexible enough to handle the projected growth in holdings and number of users, as well as the change in scope as NOAA priorities change.

Environmental issues, such as those within NOAA’s purview, tend to require input from a wide range of disciplines and approaches. Addressing such multidisciplinary problems is a challenge that often requires seamless access to many types and sources of data. Examples of integrated science that rely in part on geophysical data are given in Box 3.3. Participating in these programs will require NGDC to manage its holdings and services within a broader context and take a more integrated view of its geophysical data and services. Operating as an integrated science organization instead of three competing discipline divisions would also allow the center to respond more easily to new scientific and technological approaches.

Recommendation: NGDC should develop an integrated approach to the stewardship of environmental data and operate in such a way that share

|

BOX 3.3 Examples of Integrative Science Examples of emerging science projects that require a multidisciplinary approach and the types of data held by NGDC include the following:

Implementing these projects will require collaboration within NGDC, among the NOAA data centers, and between NGDC and other organizations in the United States and abroad. |

able services and functions (e.g., database management, software development) serve all NGDC disciplines.

Implementation of this recommendation would also allow greater cost efficiency and flexibility for future growth. The challenge is to maintain the current disciplinary strengths while evolving into a more integrated operation.

Budget

Insufficient funding was a theme that ran throughout the site review. When the committee asked why something was not being done that should be done (e.g., put more data online), the answer was invariably “lack of sufficient funds.” There is certainly an appearance of a funding crisis in the center as indicated by the lack of recruitment and the increased workload of the staff.

To meet salary requirements NGDC divisions have been energetic in securing reimbursable work. Indeed, these entrepreneurial activities are necessary to pay for some core data center functions, such as archiving. (Data acquisition and special projects might be appropriate reimbursable activities.) This “follow-the-money” strategy makes it hard for NGDC to maintain and present a coordinated focus to NOAA and the broader community. It also distracts staff from carrying out the center’s primary mission.17 Furthermore, those staff members who are able to obtain reimbursable funding are de facto penalized by having their base support reduced.18 The formula for allocating the center’s base funding (see Chapter 2) does not appear to be closely tied to identifiable center priorities and may not be an efficient use of these funds. Interestingly, in interviews with individual staff members, a few dissented from the view of a funding crisis, stating their belief that more efficient management could stretch the existing resources.

The committee feels that NGDC has substantial resources and with the right focus a great deal can be accomplished with the existing staff and budget. Increases in the size and scope of data holdings and user populations, expanded efforts in education and outreach, and new scientific initiatives at the center may necessitate concomitant growth in the budget. However, most effective use of resources first requires a clarification of the NGDC mission and a vision for the center’s future evolution. These issues are discussed in Chapter 4.

DATA MANAGEMENT

Data Dissemination

In the Internet era, users have come to expect rapid online access to data, but three factors potentially limit such access.

-

The data are not all in digital form. NGDC has a substantial patrimony of analog data (e.g., paper records; see Appendix C), much of which will have to be converted to digital form to increase accessibility and to prevent deterioration. NOAA places a high priority on this type of data rescue and provides special funding for this purpose.19

-

Metadata are often insufficient for users to discover both online and offline data. When users search for data on the Internet, they tend to rely more on the metadata and less on personal contacts with a data center or original data collector to learn about the data. It appears to the committee that NGDC captures pertinent metadata where available, although NGDC acknowledges that it does not always have the scientific expertise to maintain the quality of the data or sufficient staff to ensure that metadata are kept up to date.20 In addition, it is sometimes quite difficult to produce comprehensive and accurate metadata for analog data.

-

The Web site can be difficult to navigate. The effectiveness of a data center’s Web site is an important ingredient in ongoing efforts to keep online customers satisfied. The center has not evaluated user satisfaction with its Web site, so the following discussion is based on the experience of committee members and their colleagues. Committee members searched for data in their own discipline and were generally able to find what they were looking for, although not always directly. They found that users seeking geophysical data using a search engine on the Web are likely to arrive first at NGDC. The NGDC Web site has been arranged in such a way that it pops up with high frequency in Web searches. This is a very positive characteristic of the center, one that few centers achieve. Having arrived there, however, some users may be frustrated because in some cases NGDC does not have substantial holdings in the searched-for discipline. Examples include upper-atmosphere data, which are held mainly at NCAR, and volcano data, which are held mainly at the USGS and the Smithsonian Institution. In both cases a search engine lists NGDC first, and NGDC even lists upper-atmosphere data on the front page of its Web site, but the center holds little relevant data.21 The frustration these users feel may be compounded by the fact that the center does not always have links to external organizations where relevant data may be held, including data that have been transferred from NGDC. In the case of upper-atmosphere and volcano data, for instance, the center has no links to the CEDAR database at NCAR or to the USGS, although a link to the Smithsonian Institution is prominently displayed.

A possible area of improvement in NGDC’s Web site is the internal search tools. The committee found it easier to find the Web page of interest by using a Web search engine than by searching within the NGDC Web site. For instance, the Space Physics Interactive Data Resource (SPIDR), which allows users to retrieve datasets interactively, needs better documentation and user instructions.22 Such systems should be transparent to al-

most anyone who uses the Web site. Finally, significant portions of NGDC data are not online or in useful forms (Appendix C). Even the digital holdings are not all online or nearline, an observation that surprised the committee. Making digital data available online would greatly increase the accessibility of the holdings and would reduce the staff overhead. It would also make it easier for researchers to locate data quickly and incorporate them into research projects.23

Recommendation: NGDC should continue to convert historical analog records to digital form and make all its digital holdings available online or nearline in the near future.

Researchers working outside of their disciplines or users looking for general information may find the Web site hard to use because there is no site map and relatively few introductory pages, tutorials, or other educational materials. Those that exist are often buried where only the most ardent user will find them. Moreover, the home page of the NGDC Web site may be confusing for inexperienced users because of the jargon of the disciplines. The committee notes the importance of continuing to tune the Web site to meet the needs of a wide spectrum of users.

Archive and Stewardship

The committee found the hardware infrastructure to be modern and to have the capability to meet NGDC needs. The move toward inexpensive ($10,000 to $15,000 per node) Linux servers is reasonable and follows trends in other parts of government and in industry. The network of about 100 servers is economical and affords some protection against failure of a single primary node, although it places an additional burden on an already busy staff. The center has made a significant investment in a modern tape robotic mass storage system that will simplify future data migration tasks. However, outside organizations (e.g., NCAR, NASA) were not consulted before the equipment was purchased and benchmarks were not run to see if it was appropriate. Although the robotic mass storage system will likely meet the needs of NGDC for years to come, the center should revamp its equipment acquisition process to permit more analysis of the problem to be solved before equipment is acquired.

The management and long-term storage of data are also of concern. NGDC’s intention is to move data to modern media, but the pace of doing

so seems much too slow to assure the integrity of the data. Moreover, the data transcription policy at NGDC does not seem to be applied consistently to the data holdings. In fact, the committee was alarmed to learn that 10-year-old data are waiting to be migrated to 3590 cartridges and stored in the robotic library system and that some of these data only reside on 8-mm media. The general rule of thumb for archives is that data should be retranscribed every four to five years24 and that copies of data should be made on at least two types of media with independent hardware devices capable of reading them. NGDC staff told the committee that this plan is followed only as resources allow, suggesting that periodic transcription of data to new media and new technologies is not the highest priority for the center.

Copies of most data exist at another location, but offsite storage is not nearline (robotically accessible), making the NGDC vulnerable to a single point of failure if the primary mass storage system encounters problems. For instance, if the Internet connection into the NGDC building were to suffer a catastrophic failure, there would be no backups to provide access to the data holdings. The official archive consists of an onsite and an offsite copy of the data. Both copies are on the same media type. Another concern is that the offsite backup storage is not located at a significant distance from Boulder. Although the Boulder area is not particularly vulnerable to natural disasters other than a regional power-grid failure caused by a space weather or other severe weather storm, the proximity of the primary and backup storage locations creates the potential for significant interruption of access to data. Plans should be put into place to maintain an NGDC Web presence in the event of natural disasters, power outages, loss of Internet connectivity to the Boulder facility, or other eventualities. At a minimum the NOAA data centers could back up each other to ensure a continuous Web presence.

NGDC has devoted significant resources to ensuring that Internet connections to the center are secure and that they properly address the vulner-abilities that any data center of this size and prominence has. The committee believes that adequate Internet security and practice are in place.

The committee was pleased to see the move toward commercial off-the-shelf software for managing and presenting information. In-house development of infrastructure software should be avoided as much as possible, permitting the center to focus on writing or customizing software for accessing, retrieving, and visualizing data. The partnerships forged between

NGDC and such commercial concerns as ESRI are mutually beneficial, and the center has created many useful data handling tools on its own. Providing such tools is an important role for data centers, although it entails a long-term commitment for supporting them.

Recommendation: NGDC should improve its data stewardship, guided by practices at other data centers, to accelerate its data migration schedule and its rate of archive transcription and should also address the center and backup site disaster vulnerability.

PERFORMANCE MEASURES

As part of NESDIS oversight of the center NGDC must write a management contract with performance measures each year.25 At the time of the review NGDC had two sets of performance measures: one developed by NESDIS and applied to NGDC and one developed by NGDC (Appendix E). In addition, the center had proposed to add three more performance measures (Table 3.1) in response to a fiscal year (FY) 2002 quarterly review. The NOAA strategic plan is being revised, however, and it will contain new performance measures and milestones. Once the plan is complete NESDIS and NGDC will revise their own strategic plans and performance measures accordingly. Given the substantive changes to the NOAA strategic plan it cannot be assumed that the NGDC performance measures provided to the committee will be used in FY 2003 and beyond. Nevertheless, the committee hopes that its comments on the FY 2002 performance measures will be useful in developing the new ones.

The committee found that many of NGDC’s FY 2002 performance measures and milestones (Appendix E) are bureaucratic and do not address the issue of how well the center is progressing. For example, measures such as “ensure a safe workplace” and “alternate dispute resolution” are aimed at operating a federally supported facility well but are only marginally relevant to the success of a science-oriented data center. On the other hand, measures of the completeness of the data holdings and the ease of accessibility are quite germane to the effectiveness of a data center.

Rather than defining performance measures at the outset, a better approach is to develop a list of characteristics that define a good data center (Box 3.4). Performance measures that gauge how well the center is achieving these characteristics could then be developed. Such performance measures should be supplemented with regular reviews by an independent advisory committee.

TABLE 3.1 Proposed Additional Performance Measures and Milestones for FY 2003

|

Performance Measure |

Milestone |

|

Build authoritative long-term archives |

Establish a data quality committee to review and document the information quality of NGDC products and services Expand use of metadata records to include more data quality information in our directory systems; populate these fields |

|

Acquire valuable emerging data streams |

Establish a preliminary operational mirror site for the National Geodetic Survey’s Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS) data processing and services |

|

Contribute to significant scientific research |

Complete the external review Develop implementation plan for recommendations |

|

BOX 3.4 What Makes a Good Data Center?

SOURCE: Modified from National Research Council, 1998, Review of NASA’s Distributed Active Archive Centers, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 233 pp. |

SUMMARY

The answers to four of the questions posed to the committee are summarized below.

How well does NGDC collect the data and information it needs to effectively conduct its activities? The answer is mixed. NGDC has had a long, successful history of partnering with other organizations to acquire, disseminate, and archive data from around the world. Much of the credit goes to the center staff members, who seek out relevant data and maintain good relations with data collection agencies. However, the center is opportunistic about acquiring data, basing decisions largely on affordability. Moreover, agency requirements that principal investigators deposit data at NGDC are often not enforced. As a result the holdings are spotty and new data acquired are not always those of the highest priority. NGDC need not archive all data related to its mission, but it should have prominent links to related archives on its Web site to guide users to data of interest.

How effectively does NGDC measure customer satisfaction? At the present time NGDC does not measure customer satisfaction effectively. To measure customer satisfaction it is first necessary to identify the users. NGDC has lost direct contact with the bulk of its users, because users overwhelmingly use the Web to find data instead of contacting a staff member at the center. Moreover, other mechanisms for capturing information about users (e.g., Web-log analysis, external user advisory committee) are not fully utilized. Determining customer satisfaction is hindered by new federal laws that forbid nonrigorous surveys, such as those employed by the center in the past. A data center that cannot survey its users cannot meet their needs. However, NESDIS has obtained OMB approval for a one-time user survey of its data centers, and the results will provide important feedback on customer satisfaction.

Is NGDC organized, staffed, equipped, and supported to fulfill its mission? The committee believes that the current organizational structure hinders NGDC from fulfilling its mission. NGDC’s historical structure has led to duplication of data management functions and scientific isolation of the divisions. It would be more efficient to reorganize the center, allowing for shared functions across different divisions and more integrated scientific activities. Having greater functional and scientific integration instead of three relatively autonomous divisions would allow the center to respond more easily to multidisciplinary scientific approaches.

NGDC is appropriately equipped to fulfill its mission. NGDC’s hardware infrastructure has the capacity to meet the needs of the center, al-

though the data migration schedule should be accelerated to ensure data safety. There is a core of competent and dedicated staff, although vacancies are a problem and the median age is high. The upcoming round of retirements will present an opportunity to hire employees with needed skills, such as technical support. Supplemental scientific expertise is readily available from universities and government laboratories in the Boulder area. A strong scientific connection—either by having scientific expertise among the center staff members, by collaborating with outside scientists, or by encouraging visits from outside scientists to work with the data—is needed to ensure the quality of the data and metadata.

NGDC’s base funding is insufficient to cover all of its activities. In response staff members seek reimbursable work, which dilutes the focus of NGDC and distracts staff members from the primary mission. It is possible that by pruning activities not central to NGDC’s mission, reorganizing the center structure, and reducing staff numbers the center could rely less on reimbursable funding. Such a decision has to be made within the context of the NGDC mission, which is discussed in Chapter 4.

Are NGDC’s performance measures appropriate for tracking progress in achieving results and for judging center funding? Many of the performance measures used by NGDC in FY 2002 are bureaucratic and miss their mark. With the revision of the NOAA and NESDIS strategic plans and performance measures, NGDC has an opportunity to propose a new approach to defining performance measures—one that begins by determining the characteristics of a good data center and then defining suitable performance measures.