2

Freight Transportation Data: Current Limitations and Need for a New Approach

In the United States, information on freight movements is collected by federal agencies and other public and private entities that monitor or analyze transportation and trade activities on a regional, state, national, or international level. Widely used federal databases providing freight transportation data at the national level include the Commodity Flow Survey (CFS) from the Bureau of Transportation Statistics and the Census Bureau, the Rail Waybill Sample from the Surface Transportation Board (STB), the Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey (VIUS)1 from the Census Bureau, and the Waterborne Commerce of the United States database from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Data from these sources are available free of charge but may be subject to confidentiality constraints. For example, limited data from the Rail Waybill Sample are made available in a public use file, but more detailed commercially sensitive data can be provided to certain parties upon approval by STB. Freight data avail-

able at a charge from private organizations include trucking industry directories, economic forecasts, and customized databases, such as the Transearch database from Reebie Associates and the Port Import Export Reporting Service (PIERS) database from the Journal of Commerce.

A 1997 report (Cambridge Systematics, Appendix C) identifies approximately 35 data sources containing particularly useful information on freight transport activity and demand. A somewhat shorter but more recent list of currently available freight data sources is provided by Meyburg and Mbwana (2002, Appendix 1), and Southworth (1999) identifies principal sources of data on national and international goods movement. The reader is referred to these reports for a more detailed discussion of the diverse sources of freight transportation data.

The limitations of current data sources for the purposes of freight transportation analyses are discussed in this chapter, and a need for a new, coordinated approach to data collection to fulfill the data requirements discussed in Chapter 1 is identified.

LIMITATIONS OF CURRENT DATA

At first sight, the large number of freight transportation data sources appears to indicate a plethora of information. However, transportation analysts seeking to use data from these diverse sources often encounter problems that detract from the usefulness of the available information. The following are among the problems:

-

Variations in reporting that complicate the interpretation, comparison, and combination of data from different sources;

-

Incomplete coverage of freight movements;

-

Lack of geographic detail, particularly at metropolitan and local levels;

-

Lack of information on data reliability; and

-

Difficulties in using databases designed for purposes other than transportation analysis.

These issues are addressed in the following sections. The growing need for more timely data to accommodate shorter technology cycles and decision times is discussed in Chapter 3.

Variations in Reporting

Because existing databases have been developed independently over time to meet the specific demands of different users, they vary considerably in terms of the way that information is reported on items relevant to transportation analyses, such as origin and destination, shipment characteristics, and transport characteristics. While these variations may not present any problem for the intended users of a database, they frequently cause difficulties for analysts seeking to interpret, compare, and combine data from different sources for the purposes of characterizing freight flows.

Origin and Destination

True origin–destination (O/D) flows are defined as movements of goods between locations where they are produced and locations where they are consumed. Some databases include true O/D information, but others frequently do not. For example, databases covering a single mode may report the origin and destination of the portion of a multimodal freight movement made using that mode.

The PIERS database on waterborne freight includes O/D data taken from vessel manifests listing addresses of the shipper and consignee, although it does not include information on shipment routing or landside modes used in transporting shipments to and from inland origins and destinations. Historically, the biggest problem with the PIERS O/D data has been confusion between the location of the owner or bill-to party and the physical origin or destination of the shipment.

Trade databases in general tend to be problematic in providing true O/D data. In addition to the PIERS example discussed above, confusion can occur between administrative and physical ports of entry or exit. For example, in the case of goods entering or leaving at land ports, data providers are asked to indicate the port of entry or exit where the cargo actually entered or exited the U.S. land border. In practice, however, the reported port is often the administrative port where information about the transaction was filed—not where the cargo physically moved. Hence, some data show imports coming by land from Canada entering the United States in Dallas, Texas (BTS 2002). Clearly, such

anomalies confound efforts to characterize freight flows on the U.S. transportation system.

Shipment Characteristics

Different industries and transport modes use different measures of shipment size—differences that are reflected in freight and trade databases. Although shipment weight is widely used, commodity-based sources often specify shipment volume and may use specialized volumetric units (e.g., bushels of grain, barrels of petroleum), thereby complicating efforts to generate comprehensive flow data (see Box 2-1). Trade databases may also specify shipments in terms of their total value, particularly for import/ export purposes.

|

Box 2-1 Barrels and Tons The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Waterborne Commerce Statistics Center (WCSC) decided to change its primary source of foreign waterborne import, export, and in-transit data to Customs’ manifest data. Following publication of the statistics for 2000, it was discovered that an incorrect factor had been used to convert barrels of inbound crude petroleum to tons. The size of such shipments reported in vessel manifests may be in barrels (volume), tons (weight), or both. No correction was needed for shipments where weight was reported, but data for shipment sizes reported only in barrels required correction. The correction process resulted in a nationwide decrease of 7.1 percent in WCSC’s published weight of foreign inbound crude oil; the corrections for individual ports ranged from 0 to −13 percent. Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 2003. |

The diversity of measures of shipment size is illustrated by the example of cargo passing through Port Canaveral in Florida (Metroplan Orlando 2002). This cargo falls into one of four categories, each of which uses different measures. Thus,

-

Dry bulk and breakbulk cargoes are measured by weight,

-

Liquid bulk is measured by volume,

-

Roll on/roll off cargoes are counted in units and converted to a weight measure, and

-

Containerized cargoes are measured in 20-foot equivalent units.

Information about commodities shipped also varies considerably in both form and level of detail. In some cases, industry-specific descriptive categories may be used to describe commodities, or goods may simply be described in terms of their handling characteristics (bulk, container, breakbulk). More often, commodities are described by using classification codes. Trade databases use product-based classification systems such as the Harmonized Schedule of Foreign Trade (HS) and the Standard International Trade Classification, whereas transport-oriented databases use classifications such as the Standard Transportation Commodity Classification and the Standard Classification of Transported Goods (SCTG). Each of these classification systems uses a hierarchical series of identifiers to provide different levels of commodity detail. In the HS system, for example, preparations of vegetables, fruit, nuts, or other parts of plants are assigned a two-digit identifier (20); fruit and vegetable juices are assigned a four-digit identifier (2009); and frozen orange juice is designated by a six-digit identifier (200911). In the SCTG system, fruit and vegetable juices are designated by a different four-digit identifier (0724) and the two-digit code “20” designates basic chemicals. Conversions between the various commodity coding systems have been developed, although there is always some loss of accuracy in the translation (Southworth 1999).

Transport Characteristics

Current data sources provide a variety of information on transport characteristics such as modes of shipment and equipment used. Some sources,

such as the Rail Waybill Sample and the VIUS, cover a single mode; others, notably the CFS and the Transearch database, cover all major modes. Information on equipment type may be fairly specific. For example, the Rail Waybill Sample identifies railcar type, and the PIERS database identifies the carrier and vessel name—information that can be correlated with data from other sources, such as Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, to learn more about equipment detail. In contrast, there is a notable lack of data on truck type and weight.

Incomplete Coverage

Although transportation and trade databases provide considerable amounts of data on freight activity, some aspects of freight movements are poorly characterized—at least using publicly available data. In particular,

-

Coverage of different economic sectors and transportation modes is uneven;

-

Coverage of international shipments is incomplete; and

-

Some specific items of information, such as travel time from origin to destination, are reported only infrequently.

Disparities exist between the freight data available to business and the data available to government (Meyburg and Mbwana 2002, 7). For example, few data are available to government on the movement of freight by express urban delivery vehicles, despite the contribution of such vehicles to congestion in areas of high-density commercial activity. However, companies such as FedEx and United Parcel Service have detailed information on the nature and movements of their vehicle fleets (number and type of vehicles, number and time of day of stops, deliveries made per mile, value of commodities carried, etc.). Since such commercially sensitive data are likely to remain confidential, the following discussion of deficiencies in freight data coverage focuses on limitations in publicly available data.

Many discussions of freight data gaps take the CFS as their starting point (see, for example, BTS 1998). While this survey does not aim to provide complete coverage of all economic sectors or supply all the data items users may need, it is the major source of publicly available nation-

wide data on the movement of goods by all modes (air, motor carrier, rail, water, and pipeline) and intermodal combinations. The Transearch database is a private-sector derivative that attempts to fill some of the gaps in the CFS. The CFS and Transearch are the only two national freight databases that recognize the need for a complete picture of freight flows.

Economic Sectors and Modes of Transport

In terms of economic sector coverage, the CFS captures data on shipments originating from manufacturing, mining, wholesale, and selected retail establishments. It does not cover establishments involved in farming, forestry, fishing, construction, and crude petroleum production; households; governments; foreign establishments; and most retail and service businesses (BTS 1998). Some of these gaps can be filled by using data from sources covering single modes, such as the Rail Waybill Sample and the Corps of Engineers and PIERS databases on waterborne freight, all of which provide comprehensive coverage across economic sectors.

While the CFS provides some coverage of all modes of transport, there is widespread agreement among data users that the coverage of air and truck shipments is limited. Air freight is particularly important for establishments not included in the CFS. Although air freight data can be obtained from other sources, there is a general lack of detailed information on commodity movements by air for both domestic and international freight (BTS 1998). The CFS collects data on freight movements by for-hire and private trucks. However, the activities of many firms involved in the trucking industry have proven difficult to track (Southworth 1999), and truck freight data are widely acknowledged to be both complex and deficient. One of the short-term action items suggested by participants in the 2001 Saratoga Springs meeting was to concentrate on truck data “since this is where the bulk of the problems reside” (Meyburg and Mbwana 2002, 25). The deficiencies in truck data are a major concern because of the importance of motor carriers for moving freight within the United States. In 1997, single-mode movements by for-hire or private truck accounted for more than 60 percent of the tonnage moved in U.S. commercial freight shipments and almost 30 percent of the ton-miles (BTS 2001). Trucks also play an important role in movements involving multiple modes, such as truck-and-rail and truck-and-water.

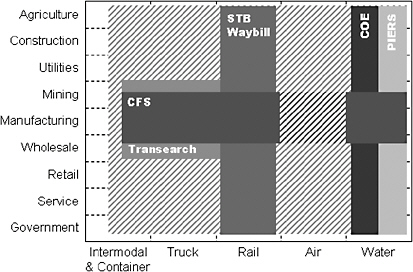

A schematic representation of the coverage of freight movements provided by important data sources for different economic sectors and modes of transport is given in Figure 2-1.

International Movements

Information about the domestic portion of international goods movements has become increasingly necessary as a result of the growing importance of international trade to the U.S. economy and expanding competition among transportation providers in North America (BTS 1998). The CFS captures some information on these movements but is notably deficient in its coverage of imports. Because the survey samples domestic shipper establishments, it cannot capture information on shipments from foreign establishments. Imported products are included in the CFS at the point where they leave the importer’s domestic location

Figure 2-1 Coverage of freight movements for different economic sectors and modes of transport. (CFS = Commodity Flow Survey; STB Waybill = Surface Transportation Board’s Rail Waybill Sample; COE = Army Corps of Engineers’ Waterborne Commerce of the United States database; PIERS = Port Import Export Reporting Service database. Source: Rick Donnelly, PBConsult, Inc.)

(which is not necessarily the port of entry) for shipment to another location in the United States. Thus, the CFS does not cover the first leg of import shipments (TRB 2003a).

Foreign trade data may be helpful in filling gaps in CFS import data and in establishing comparisons among different data sources. However, such data have traditionally focused on economic transactions rather than physical commodity flows and often provide only limited information about the transportation aspects of the transaction. In the case of the Canadian trade statistics, the data are likely to show the dollar flows between one large multinational firm and another or between divisions or factories within a single firm. The actual flow of goods may take place between subsidiary locations far from those physically handling the import or export transactions.

Specific Data Items

Data on shipment frequency, travel time from origin to destination, and costs of transportation would be useful in assessing the performance of the freight transportation system in terms of cost and timeliness. Data on routing and time of day would also be valuable in assessing strategies for alleviating congestion and identifying opportunities for modal diversion. The CFS does not collect such data because of concerns about overburdening survey respondents, and publicly available data on costs, travel time, and system reliability from other sources are too limited to compile a complete national picture (BTS 1998). A recent report on freight capacity notes that the available aggregate data are generally inadequate for identifying local constraints on transportation systems (TRB 2003b).

Lack of Geographic Detail

Most national data sets, such as the CFS, do not provide the level of geographic detail required by analysts seeking to understand freight transportation at metropolitan area and county levels. There is an outstanding requirement for more focused data on freight movements at the metropolitan level to provide insights into transportation demand, the relationships between freight movement and business patterns, and freight flows through key corridors (BTS 1998). These metropolitan-level data

need to be linked to data on global, national, and regional freight movements, since the latter have an important influence on what happens at the metropolitan level.

Much of the data already collected by the CFS could be useful in providing the levels of geographic detail required by analysts. However, Title 13 restrictions on the disclosure of company-specific information prevent the release of such data. The CFS data products present aggregate data to prevent the identification of individual establishments. The public release of much of the detailed trade data is similarly restricted to protect the confidentiality of data providers, notably carriers.

Sample size constraints also contribute to the lack of geographic detail in the published CFS data. As the sample size decreases, the statistical variability of the data increases. If the sample size is too small, the data may not be sufficiently reliable to be useful for analysis at the required level of geographic detail (TRB 2003a). The CFS provides information on state-to-state flows, but is not intended to provide detailed coverage of local freight movements. The information needed by local decision makers far exceeds the capacity of any single national survey, and local data collection efforts that supplement national surveys appear to be a more promising approach to remedying the current lack of detailed geographic data (BTS 1998).

Lack of Information on Data Reliability

Because many transportation-related investment decisions involve large expenditures and have long-lived implications, it is important to assess the reliability of data used to inform these decisions. Some sources, such as the CFS, are well documented in terms of the origin, quality, and limitations of the data they provide, thereby allowing users to assess data reliability. Others provide only limited insights into how data were obtained and processed, with the result that users risk providing information and advice on the basis of questionable data.

One of the most important distinctions affecting data reliability is that between “real” and synthesized data. The synthesis of missing data may sometimes be the only feasible method of providing timely information; this approach also avoids the expense of data collection and processing. However, synthesized data depend on the assumptions built

into the analytical models used to generate them and how well these models replicate reality. Furthermore, while such models may be helpful, data are required to validate them. In principle, real data obtained from survey questionnaires, bills of lading and other trade-related documentation, and continuous electronic data streams generated by traffic monitoring and control systems provide a more solid basis for decision making, although care is still needed in assessing data reliability.

The design of any data collection effort affects the reliability of the resulting data. For the many existing freight data sources based on surveys, sample size is a key determinant of data quality and reliability. The methods of data collection are also important. For example, data taken from vessel manifests and bills of lading are not subject to the same concerns about nonresponse bias as data gathered by using survey questionnaires.

Most federal data sets present real (as opposed to synthesized) data and provide much of the information needed by analysts to assess the reliability of these data. Commercial data sets tend to be less transparent. For example, they may incorporate proprietary data whose origin and reliability are not reported. They may also use proprietary methods to combine different data sets and synthesize data and may interpret reported data to generate information requested by clients. In many cases, little information is provided about the assumptions used in generating derived data products, with the result that their reliability is unknown.

Difficulties in Using Databases Designed for Other Purposes

Commodity flow–type freight databases typically include data on commodity type, shipment origin and destination, shipment weight, and shipment value for one or more modes of transport. Supplementary freight databases do not contain any commodity flow data but provide information that can be used in the development of freight models. For example, the VIUS microdata provide information on percentages of loaded miles by commodity for vehicles on an annual basis. (The records are masked to avoid possible disclosure of individual vehicles or owners.) However, the survey does not provide data on when during the year these commodities are carried or on the origin and destination of ship-

ments. Trade databases contain information about freight movements to and from, and sometimes within, the United States.2

The supplementary freight and trade databases were not designed to track freight flows. For example, VIUS data are used to perform cost allocation analyses, study safety issues, determine user fees, and estimate per-mile vehicle emissions.3 Many trade databases provide information on goods entering and leaving the country to inform decisions about the legal admissibility of and duty applicable to imported merchandise, the safety of food products for consumption, and the like. Consequently, the data reported may be incomplete for the purposes of transportation analysis or may include inconsistencies that are difficult to reconcile when developing information on freight flows. Two examples illustrate these difficulties.

The source documents (ship manifests, bills of lading) used to compile the PIERS database on waterborne freight are intended to provide evidence of liability and are not developed primarily as a source of freight transportation data.4 For example, a bill of lading functions as a receipt, as evidence of a contract of carriage, and as a document of title to the goods being shipped. Because the ocean carrier may be responsible for transporting the goods only from Port A to Port B, the bill of lading may not show the true O/D of the shipment, and the PIERS database will be similarly deficient. A transportation analyst seeking to establish a complete picture of the freight movement will, therefore, need to find other data describing the initial movements from the true origin to Port A and the final movements to the true destination from Port B.

The province of Ontario in Canada relies heavily on trucking knowledge gained from roadside surveys of carriers. While such surveys provide reliable vehicle data and relatively accurate commodity data, they cannot provide data on commodity value—data that are critical to informing investment decisions and building linkages with economic input/output models. In light of the economic importance of trade with the United

|

2 |

For further discussion of trade databases and the two major categories of freight database (commodity flow and supplementary), the reader is referred to Freight and Trade Data Information, Center for Transportation Research and Education, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa (www.ctre.edu/research/bts_wb/cd-rom/freight_intro.htm). |

|

3 |

Further information on the use of VIUS data is provided on the Census Bureau’s website (www.census.gov/econ/www/viusmain.html). |

|

4 |

As reported to the committee by Bill Ralph, PIERS, September 19, 2002. |

States and emerging issues relating to trade corridors, attempts have been made to obtain commodity values from other sources. However, data from shippers, receivers, the census, taxation officials, and Customs include different interpretations of commodity value, depending on the intended use of the data. Thus, the reported commodity value may reflect the insured value (possibly inflated), value added at different stages of manufacture, deliberate underreporting of value to Customs, nonreporting of in-bond or tariff-exempt flows, self-assessed value with the intent to avoid interference and subsequent secondary customs inspection, wholesale value, retail value, manufacturer’s estimate of costs to manufacture, transportation costs, and so on. Thus, there is no single reliable source of unambiguous data on commodity value to complement the information from roadside surveys.

NEED FOR A NEW APPROACH

Participants in the 2001 Saratoga Springs meeting on freight data needs observed that data collection, storage, and distribution are expensive activities, and they urged data users to make full use of available data (Meyburg and Mbwana 2002). They also noted that “any effort to collect new freight data should be preceded by an understanding as to why the new data are needed” (p. 23). Having established the reasons why freight data are required (see Chapter 1), the study committee initially considered the possibility that a comprehensive national picture of freight flows might be developed by combining existing data sources without the need for modifications to current data-gathering procedures or additional data collection initiatives. The committee quickly concluded that creating a comprehensive national freight database by patching together existing data sources is not feasible. The lack of coordination among different data collection efforts creates fundamental problems not readily overcome. In particular, the niche data products can be linked only with considerable difficulty and accompanying loss of accuracy, and even then important data gaps remain.

The committee concluded that a new approach is required to provide the freight data needed to inform important policy and investment decisions such as those described in Chapter 1. In the committee’s view, the coordination of freight data collection efforts through the imple-

mentation of a national freight data framework offers improvements over the current approach. Such a framework needs to recognize and build on the strengths of current data sources, but also establish linkages among different data sources in an effort to eliminate unconnected data “silos.” Similarly, any new data collection initiatives for filling data gaps need to be designed so that the resulting data can be readily integrated with data from other sources.

A recent National Research Council report notes that “when separate datasets are collected and analyzed in such a manner that they may be used together, the value of the resulting information and the efficiency of obtaining it can be greatly enhanced” (NRC 2001, 7). Thus, the committee anticipates that a coordinated approach to collecting freight data should be more efficient than current efforts. The uncoordinated collection of trade data by different federal agencies provides an interesting analogy to the situation with freight data. Currently, traders importing or exporting goods provide information to each individual trade agency by using a variety of different automated systems, numerous paper forms, or a combination of systems and forms. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has estimated that submission of redundant information and preparation of documentation amount to 4 to 6 percent of the cost of the merchandise. The International Trade Data System (ITDS), a federal government information technology initiative, aims to develop a system that will allow traders to submit one set of standard electronic data for imports or exports. ITDS will then distribute the data to the relevant federal agencies on a need-to-know basis. Requirements for traders to submit redundant information to multiple federal agencies will be eliminated, with associated reductions in cost and respondent burden.5

A new, integrated approach to gathering freight data will need to offer advantages similar to those of ITDS in terms of more cost-effective data collection and reduced respondent burden. The approach will also need to be more effective than the current fragmented system in providing data that meet the needs of a range of users. A concept for a national freight data program that aims to meet these ambitious goals is presented in the next chapter.

|

5 |

ITDS Background (www.itds.treas.gov/itdsovr.html). |

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

BTS Bureau of Transportation Statistics

NRC National Research Council

TRB Transportation Research Board

BTS. 1998. Transportation Statistics Beyond ISTEA: Critical Gaps and Strategic Responses. BTS98-A-01. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

BTS. 2001. Transportation Statistics 2000. BTS01-02. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

BTS. 2002. International Trade Traffic Study (Section 5115): Measurement of Ton-Miles and Value-Miles of International Trade Traffic Carried by Highways for Each State (draft). U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 1997. NCHRP Report 388: A Guidebook for Forecasting Freight Transportation Demand. TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

Metroplan Orlando. 2002. Freight, Goods and Services Mobility Strategy Plan. www.metroplanorlando.com/msplan.

Meyburg, A. H., and J. R. Mbwana (eds.). 2002. Conference Synthesis: Data Needs in the Changing World of Logistics and Freight Transportation. New York State Department of Transportation, Albany. www.dot.state.ny.us/ttss/conference/synthesis.pdf.

NRC. 2001. Principles and Practices for a Federal Statistical Agency, 2nd ed. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Southworth, F. 1999. The National Intermodal Transportation Data Base: Personal and Goods Movement Components (draft). Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

TRB. 2003a. Letter Report on the Commodity Flow Survey. National Research Council, Washington, D.C. gulliver.trb.org/publications/reports/bts_cfs.pdf.

TRB. 2003b. Special Report 271: Freight Capacity for the 21st Century. National Research Council, Washington, D.C.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2003. Corrections to CY2000 Published Crude Oil Import Statistics. www.iwr.usace.army.mil/ndc/usforeign/index.htm.