3

Concept for a National Freight Data Program

A conceptual plan for a national freight data program is presented in Appendix A under the section entitled “Product Definition.” The plan is based on an initial concept proposed by the committee’s consultant, Rick Donnelly, and further developed by Dr. Donnelly after extensive discussions with the committee at its second and third meetings. This chapter provides the committee’s commentary on Dr. Donnelly’s proposed plan.

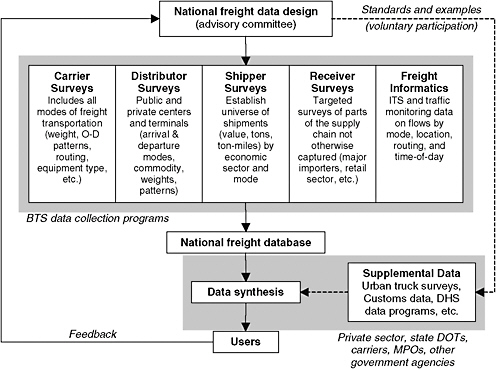

The framework for a national freight data program illustrated in Figure 3-11 and described in Appendix A proposes establishing an advisory committee to oversee the design and implementation of a multifaceted data collection program. An integrated program of freight surveys and a freight informatics initiative that gathers data from electronic data streams, such as those associated with intelligent transportation systems (ITS) and electronic data interchange (EDI), would provide the data needed to populate a national freight database. These data would be supplemented by

|

1 |

Figure 3-1 is adapted from Figure A-1 of Appendix A. |

Figure 3-1 Proposed framework of a national freight data program. [BTS = Bureau of Transportation Statistics; O-D = origin–destination; DHS = Department of Homeland Security; MPO = metropolitan planning organization; state DOT = state department of transportation. Source: Adapted from a paper prepared for the committee by R. Donnelly (Appendix A).]

data from other sources, such as urban truck surveys, and by synthesized data. The resulting databases would be made widely available to the user community, whose comments and feedback would help inform further development of the framework.

In the committee’s opinion, the framework shown in Figure 3-1 forms a guide for improving on the current patchwork of uncoordinated freight data collection efforts by a more systematic approach that eliminates unlinked data “silos.” The proposed framework focuses on increasing the linkages between different sources of data and filling data gaps to develop a comprehensive source of timely and reliable data on freight flows.

The committee recognizes that the implementation of a national freight data framework such as the one proposed will require a sustained effort—and funding—over many years and will involve many technical

and organizational challenges. From a technical perspective, the amount of information required is large, and some of the information needed by decision makers—such as comprehensive data on route, time of day, and commodity for highway freight movements—has not previously been collected in the United States. Research will be needed in areas such as survey methodology and data processing, and the effort will not succeed without innovative, low-cost data collection strategies.

From an organizational perspective, the success of a national freight data program to implement the framework will depend on the participation of diverse public- and private-sector organizations at various levels. The assignment of responsibilities for tasks such as the conduct of surveys, database development, and data synthesis will require further discussion and elucidation as part of program development and implementation activities. For example, the committee does not envisage the Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS) assuming responsibility for all the data collection activities (survey programs and the freight informatics initiative) grouped together in Figure 3-1 under the designation “BTS data collection programs.”

Instead, the committee anticipates that much of the data will continue to be collected by the same organizations as today (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Surface Transportation Board, Census Bureau, etc.). A coordinating body such as BTS, working under the guidance of an advisory committee of stakeholders and data experts,2 will take measures to encourage harmonization of these data collection efforts and will coordinate access to the data as appropriate. Public- and private-sector roles are discussed in the section of this chapter addressing challenges in implementing a national freight data framework.

The committee has deliberately proposed a flexible data framework that can evolve as research results indicate which data collection strategies are likely to be the most fruitful. For example, several types of survey are proposed, but it is unlikely that all will be pursued concurrently or that equal effort will be devoted to each. Since resources are limited, it will be necessary to identify the most promising avenues for development and implementation and prioritize funding allocations accordingly. The committee recognizes that, in some instances, further investigation

may reveal certain features of the conceptual plan to be impractical or not cost-effective.

Despite the many challenges to implementing a national freight data framework, the committee observed widespread agreement among data users—including high-level decision makers—that current freight data sources are not meeting the need for reliable data to inform investment, planning, and policy decisions. Thus, many stakeholders may be willing to support and participate in a national freight data program that offers benefits for diverse data users—and ultimately for the national transportation system as a whole. Nonetheless, it will be important to encourage the participation of data providers by clearly defining anticipated benefits. If the imposition of focused private costs on survey respondents appears to offer only diffuse benefits, the necessary broad participation is unlikely to be achieved.

The rationale for the conceptual plan presented in Appendix A is described in the remainder of this chapter, and additional insights into some of the challenges to be addressed in implementing the plan are provided.

RATIONALE FOR CONCEPTUAL PLAN

The conceptual plan for a national freight data program comprises five major components:

-

A national freight data framework,

-

An integrated program of freight surveys,

-

A freight informatics initiative,

-

Freight data synthesis, and

-

Standard survey methodologies.

The supporting rationale for each of these components is discussed below.

National Freight Data Framework

Because it would be impractical for the federal government to meet all the freight data needs of all users, the proposed national freight data framework facilitates opportunities for combining data from a variety of sources and identifies possible roles for a range of stakeholders, including the fed-

eral government, the private sector, state departments of transportation, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), and research organizations. The framework comprises a series of modules, as follows:

-

A national freight database will be populated through an integrated program of freight surveys and a freight informatics initiative. The survey program itself comprises another series of modules, namely, carrier surveys, distributor surveys, shipper surveys, and receiver surveys.

-

A freight data synthesis program will fill data gaps, particularly in the short term before all of the proposed data sources are fully established.

-

Supplemental data collection activities will provide additional specialized data to complement the data in the national freight database. Standard survey methodologies and examples of their use will be provided to guide supplemental data collection and help ensure compatibility with national data.

The committee anticipates that different users will use the various modules in different ways. For example, users interested in local transportation issues will gather supplemental data from their own jurisdictions to obtain the level of geographic detail they require. Following the practices and guidelines in the standard survey methodologies will help these users ensure that their data can then be combined with data from the national freight database. Other users will combine data from the national freight database with synthesized data to fill gaps that are too difficult—and expensive—to fill by using surveys or other data-gathering techniques. Yet others will leverage federal economic or trade data programs, such as the International Trade Data System (ITDS) of the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection, to obtain supplementary data that they will combine with data from the national freight database.

The provision of training and education in the use of freight data resources and methods will be an important component of efforts to implement the framework. As discussed in a report from BTS (1998), the availability of sophisticated models, complex analytical methods, and large data sets to relatively inexperienced users necessitates new approaches to training. Data customers are no longer limited to analysts in a few federal agencies and large consulting companies, and training programs will need to recognize user diversity. While the proposed frame-

work offers different users the option to employ the various modules in different ways, many will require training so they understand how to use the modules correctly and obtain meaningful results.

Since funding for new freight data initiatives is limited, simultaneous exploration of all possible data collection and synthesis options is not realistic. The advisory committee responsible for guiding the design and implementation of the national freight data framework will need to weigh the costs of obtaining data against the potential benefits when advising on program priorities and a timetable for development. The proposed modular approach lends itself to an incremental development process whereby various options can be investigated as resources permit, as new technologies become available, and as opportunities arise to leverage ongoing activities. Under this approach, implementation of the framework could focus initially on developing the national freight database rather than devoting equal effort to all aspects of the initiative. A similar phased approach could be adopted in populating the database. For example, ITS offers the possibility of collecting routing, time, carrier, and origin–destination data for trucks but cannot at present routinely determine the commodity carried or certain truck characteristics. Therefore, a carrier survey could be used initially to obtain the commodity and vehicle data needed to complement shipper survey data. The carrier survey could then be phased out and replaced by more sophisticated ITS data collection methods as these become available.

Table A-1 (Appendix A) proposes a schedule for a national freight data program to implement the proposed framework. The committee views the task breakdown and sequence outlined in Table A-1 as a helpful and appropriate basis for discussion and development by the freight data advisory committee. Further definition and detailed sequencing of the tasks will be needed, probably in the form of a road map. Clearly, the availability of funding and the pace of research will determine how many years the entire process will take.

Integrated Program of Freight Surveys

Comprehensive data on freight flows cannot be collected by using a single type of survey. As discussed in Appendix B, the complexity of supply chains and the number of agents involved in moving goods from their ori-

gin to final destination make it impossible to design a single survey process that would provide data on all aspects of freight flows. The shipper, receiver, customer, carrier, regulator, and distributor all make or influence decisions about freight movements, and most have only limited knowledge of the factors influencing decisions made by others. For example, a shipper may specify a date and time by which certain goods need to arrive at their destination but may not know (or need to know) the route traveled or the modes of transport used. Thus, a shipper survey is unlikely to provide good route data and may provide only incomplete modal information. Additional data from carriers are needed to provide some of the information required for a national freight database. Some analysts already fuse carrier and shipper data, albeit with some difficulty, to inform their investigations. For example, carrier manifest data from the Port Import Export Reporting Service database have been combined with customs data supplied by shippers to inform maritime infrastructure planning and analyses.

Some understanding of the supply chain is necessary to identify the best ways of gathering the various items of data needed by different users.3 For example, in deciding how to gather data on goods movements, it is important to understand that a carrier who transports goods from a warehouse to a distribution center may not know the true origin of the goods or their final destination. Thus, although a carrier survey (for example, a roadside truck survey) can potentially provide good data on mode, routing, time of day, and vehicle size and configuration, such a survey may well be of limited use in providing reliable data on the true origin and final destination of goods movements.

A dramatic increase in the importance of warehousing and distribution centers over the last two decades suggests that distributor surveys could provide useful data on freight movements (see Appendix B). When goods move through an intermediate point, such as a marine port or truck terminal, the visible linkage between the original shipper and ultimate receiver is broken. However, surveying a transportation terminal or distribution center could provide information on movements into and out of this intermediate location, as well as on the transition between the two movements. Despite their potential advantages, distributor surveys are conducted only

infrequently. Possible impediments to such surveys include the need to secure the cooperation of private-sector owners of distribution hubs and concerns over protecting the confidentiality of clients.

A judicious balance among the different types of survey (and other data collection methods) will likely be needed for cost-effective development of a national freight database. This balance is expected to change over time as experience is gained and new data collection opportunities arise.

Because different types of surveys have different data gaps, they can, in principle, be used to complement each other. Southworth (1999) notes that two or more data sources can be combined by a process known as “data fusion” to create more complete movement information without the additional costs of further data collection. However, as discussed in Chapter 2, different surveys have been developed independently to provide data to meet specific, and diverse, needs. As a result, the technical challenges in integrating data from different surveys are often formidable, in large part because differing data collection strategies and data definitions raise concerns about the quality and comparability of the resulting combined data. In addition, errors may occur because of confusion arising from the different ways of describing and quantifying shipments. Therefore, an important feature of the integrated program of freight surveys is the development of survey designs providing data that can readily be fused to provide users with the information they require.

Data fusion is a complex and challenging process, as the examples discussed by Southworth (1999) illustrate. Thus, specialized technical expertise will be needed to identify and develop approaches for facilitating the combination of data from different sources. Common data elements across surveys—such as commodity classifications, geographic information, and mode definitions—would not overcome all the difficulties but could aid in the fusion process. For example, geographic information systems could be used to connect different surveys that collect precise information on vehicle location (latitude and longitude) at specified times.

Freight Informatics Initiative

The budget for the 2002 Commodity Flow Survey (CFS), which collected data on 2.7 million shipments from 50,000 domestic shipper es-

tablishments, is $13 million. Order of magnitude cost estimates indicate that developing a comprehensive national freight database by using only data collection strategies similar to those currently used for the CFS is unrealistic. Affordable collection of the large amounts of data needed to provide users with high-quality data at useful levels of geographic and commodity detail will require innovative and less costly strategies.

Although the use of technology—for example, electronic reporting using Web-based survey questionnaires—offers opportunities to improve data quality and reduce both cost and respondent burden in survey programs, it is unlikely to result in the major cost reductions needed to populate a national freight database of the type envisaged. In contrast, passive data collection methods that take advantage of continuous electronic data streams from traffic-monitoring systems or mine transaction data from EDI systems promise large quantities of data at low cost. The purpose of the freight informatics initiative is to investigate the technical and institutional aspects of such passive data-gathering approaches. While current practical experience with passive data collection is limited, the committee believes that without such alternatives to conventional surveys the costs of developing a comprehensive national freight database will be prohibitive. Furthermore, passive data collection may be the most promising approach for gathering the reliable data on shipment routing and time of day required by many users. Given the importance of low-cost data collection methods for the overall success of the framework initiative, the committee would like to see an early emphasis on freight informatics pilot studies as part of the framework implementation process.

Freight Data Synthesis4

Ideally, the national freight database will contain “real” data, gathered by using a range of surveys and passive data collection methods, rather than synthesized data generated by simulation techniques. However, participants in the November 2001 Saratoga Springs meeting noted that data collection, storage, and distribution are expensive activities and stressed that data users should make full use of available data and where possible

“use analytical models to fill in data gaps” (Meyburg and Mbwana 2002, 23). Gathering the data needed to fill many of the current gaps will take time and resources, and, at least in the short to medium term, the national freight database is likely to contain important amounts of synthesized data. In the longer term, the replacement of much of the synthesized data by real data should allow users to have more confidence in the data they use to inform decisions.

Standard Survey Methodologies

The freight data needed for all proposed applications exceed current and expected future capabilities of national freight data sources, as illustrated by the examples given in Chapter 1. It is not clear that a national freight database can, or should, provide the large amounts of data required to capture the diversity of establishment sizes and inbound/outbound flows for all MPOs, counties, and local jurisdictions nationwide. Furthermore, even within a category such as MPOs, there is considerable variability in data requirements. For example, some MPOs require detailed data to address serious congestion problems, whereas others have little need for such information. In the committee’s view, the national freight database should focus on providing a large number of users with frequently requested data items—such as origin and destination, commodity information (characteristics, weight, value), modes of shipment, routing and time of day, and vehicle or vessel type and configuration.

The national freight database will form a foundation on which users can build their own data sets. Thus, users concerned with regional markets and metropolitan, county, and local issues will be able to supplement the national database with localized data to obtain the degree of geographic resolution they require. The inclusion of standard survey methodologies in the national freight data framework is intended to assist users in generating supplemental data compatible with the national freight database.

The committee envisages that standard survey methodologies will address survey design issues, including determination of the sample size needed to provide the required level of geographic detail with an acceptable degree of reliability. Different methods of data collection (mail, Web-based survey, telephone, etc.) and anticipated response rates will also need to be considered. To help ensure consistency, key items such as origin and

destination will need to be clearly defined, as will standard categories of truck type and size. Recommended best practices will address a range of survey topics, including the use of commodity categories with the potential to “roll up or down” to broader or narrower categories. Advice will also be required on assumptions about the first point of rest for freight shipments and how to avoid double counting. Examples of well-designed survey instruments that have yielded quality data will be provided for guidance.

CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTATION

The purpose of this report is to provide a blueprint to guide the reengineering of today’s disjointed patchwork of freight data into a more integrated and useful national freight data program, rather than to describe the detailed implementation of the framework illustrated in Figure 3-1. However, the committee considers it important to highlight some of the challenges likely to be faced in the implementation process. Some general principles pertinent to this implementation are discussed in the following sections, and issues relating to data quality and timeliness, new data collection opportunities, confidentiality, and the roles of the public and private sectors are identified. Some specific issues that may well arise during implementation of the framework are discussed in Appendix D.

General Principles

Although many current sources of freight data are far from ideal for the purposes of freight transportation analyses, the national freight data program will need to be developed in the context of these sources. The content and detailed structure of the data framework will evolve to reflect research findings and practical experience, but there will be a continuing need to provide consistent data for trend analysis. “Wiping the slate clean” by initiating a set of totally new data collection programs risks jeopardizing the ability to study trends in freight movements over time— a subject of considerable importance for many investment and policy decisions. Thus, implementation of the national freight data framework will need to be an evolutionary, rather than a revolutionary, process that builds on experience with a range of surveys, takes account of data classifications and standards, and establishes links to previous data sets for

the purposes of time series analyses. The data in the national freight database will also need to be updated on an ongoing basis. These updates will need to take account of the evolving nature of the data framework in such a way as to permit trend analyses.

Initiatives to modify or replace current surveys will need to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of current data sources, as illustrated by two examples. First, the CFS has been criticized because of its incomplete coverage and lack of geographic detail. Nonetheless, because the CFS is coupled to the Economic Census, response is mandatory and response rates are correspondingly high (approximately 75 percent for the 1997 CFS). Decoupling any successor to the CFS from the Economic Census could well result in a reduction in response rate—and an associated deterioration in data quality—unless an alternative mechanism could be established to require response to the new survey. Furthermore, diverting resources away from the CFS to other freight data initiatives could result in a reduced sample size and a resulting reduction in the usefulness of CFS data. Nevertheless, new data collection initiatives could remedy some of the deficiencies of CFS data, resulting in an overall improvement in the coverage and quality of multimodal freight data.

Second, data sets from the Surface Transportation Board (Rail Waybill Sample) and the Corps of Engineers already provide useful carrier data on rail and waterway movements, respectively. Rather than duplicate these efforts, it would seem appropriate for the national freight data program to focus on filling gaps and providing better data where current coverage is inadequate—for example, in the areas of motor carrier and air freight data.

Data Quality and Timeliness

Users need to have confidence in the data they use to inform decisions. In particular, most users would like to have information on how data were obtained, together with an estimate of their reliability. Although the widespread use of various commercial databases demonstrates the existence of a role in the marketplace for data that are not entirely transparent, many decision makers indicated to the committee that they would like to see a clear distinction made between real and synthesized data. Data also need to be provided in a timely fashion if they are to be useful for de-

cision making. Participants in the Saratoga Springs meeting observed that government long-term planning now has to provide for infrastructure capacity needs and efficient operations with shorter lead times because of the shorter life cycles of technology products (Meyburg and Mbwana 2002). Short times for decision making require more complete and detailed information sooner than is provided by data sources such as the 5-yearly CFS. The development of survey designs for the integrated program of freight surveys will need to take account of these user requirements for timely and reliable data.

The freight data business plan presented in Appendix A proposes moving away from periodic (5-yearly) surveys toward continuous surveys to obtain more timely data for decision making. The motivation for this proposed move is very similar to that which stimulated the Census Bureau to develop the American Community Survey (ACS). Rapid demographic and technological change meant that a static, once-in-a-decade snapshot of the nation’s population was no longer a satisfactory basis for informing a wide range of policy decisions and the allocation of billions of dollars of federal funds. Therefore, Census Bureau managers concluded that the design of the decennial census needed to be simplified and long form data collection made more timely in response to stakeholders’ requests. The ACS development program, which collects demographic and socioeconomic data in 3-month cycles, divides a huge nationwide workload into manageable pieces over a longer time frame, with the result that data products can be released much sooner than under the conventional episodic approach (Census Bureau 2001). From a development perspective, continuous surveys offer the potential to obtain timely feedback on new data collection strategies and other survey design features, rather than having to wait several years to learn how a new approach is working in practice. Thus, if continuous data collection is adopted for the integrated program of freight surveys, the committee hopes that relatively rapid progress can be made in developing and refining survey designs. The cost implications of a move to continuous data collection are dependent on the details of the survey design (sample size, frequency, coverage, and the like) and will require further study.

Research will be needed to optimize the designs of the proposed rolling series of cross-sectional freight surveys. For example, a better understanding of the changed (and changing) nature of commodity

distribution patterns would inform the development of effective sampling strategies. New business practices, such as freight logistics and just-in-time manufacturing, have changed the nature and volumes of goods shipped and the frequency, origins, and destinations of shipments. Thus, while the movement of bulk goods (e.g., grains, coal, and ores) still makes up a large share of the tonnage moved on the U.S. freight network, lighter and more valuable goods (e.g., computers and office equipment) now make up an increasing proportion of what is moved (FHWA 2002). A better understanding of the patterns of movement of these nontraditional commodities, possibly obtained through analysis of ITS data, would help inform decisions about survey design, notably sampling.

Wherever possible, survey research in support of the national freight data program should draw on the experience of public- and private-sector organizations in the United States and overseas. For example, there are valuable lessons about carrier surveys to be learned from Canada’s National Roadside Study (NRS), a joint effort by federal and provincial transportation officials to conduct roadside carrier surveys capturing information on vehicle, cargo, trip, driver, and carrier for both international and domestic intercity trips. The 1999 NRS collected information from approximately 65,000 truck intercepts at 238 data collection sites spread across the Canadian road network. The surveys attempt to provide much of the detailed geographic information needed by analysts and planners. For example, data are gathered on highways used, stops along the trip, international border crossings, provincial boundary crossing points, and both trip and commodity origin and destination in an effort to identify both carrier and shipper logistics.5

The use of technology to collect survey data is expected to result in improved data quality, with the possible added benefits of reduced cost and reduced respondent burden. For example, Canadian roadside truck surveys currently involve photocopying waybills for reference purposes. In the future, it may be possible to take a digital picture of the truck with a personal digital assistant to confirm the observations of those conducting the survey. Web-based surveys also show promise for a range of applications. For example, the implementation of a Web-based questionnaire

|

5 |

Further information on the NRS is available on the website of the Eastern Border Transportation Coalition (www.ebtc.info). |

for the 2002 Economic Census will allow businesses to extract data directly from their own spreadsheets rather than having to transcribe information onto a questionnaire form, thereby reducing the likelihood of transcription errors. This electronic reporting is expected to significantly lower the respondent burden and associated reporting costs incurred by some large businesses, as well as save the Census Bureau both time and money.6

During the early stages of implementing the national freight data framework, the emphasis is likely to be on the quality and timeliness of data in the national freight database, and particularly the data gathered as part of the integrated program of freight surveys. The committee identified a clear role for BTS, as a federal statistical agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation, to initiate and stimulate activities aimed at improving data quality and timeliness. In this context, consideration could also be given to including quality control procedures in the data framework, perhaps by incorporating predefined performance measures against which to assess survey designs and evaluate the statistical reliability of data sources.

In the longer term, the lessons learned from developing the freight survey program are expected to inform the development of the standard survey methodologies. Experience with the Canadian NRS suggests that special efforts may be needed to encourage organizations to follow survey guidelines designed to generate quality data. While there is consensus among the provinces that driver interviews should be conducted by local staff familiar with regional travel and vehicle characteristics, important variations still occur. Different groups with different objectives (enforcement, planning, policy making, etc.) gather the data, reflecting each province’s reasons for participating in the NRS. Some focus on collecting data on vehicle weight and dimensions for enforcement purposes, and others focus on collecting data on trip details (origin and destination, highway used, border crossings) for planning purposes.7 While such differences are understandable, it is important to capture local detail in a well-planned and consistent manner when national data for a wide range of uses are collected.

|

6 |

2002 Economic Census: Electronic Reporting (www.census.gov/epcd/ec02/ec02electronic.htm). |

|

7 |

As reported by committee member Robert Tardif, Ontario Ministry of Transportation, during committee discussions. |

Also in the longer term, the harmonization and streamlining of data collection efforts should result in data quality improvements as data from different sources are used to perform consistency checks and cumbersome and error-prone data-gathering methods are superseded.

New Data Collection Opportunities

In the short term, conventional transportation surveys (shipper surveys, carrier surveys, and the like) are expected to be the main source of data in the national freight database. However, because such surveys are frequently expensive and a burden on respondents, it will be important to identify and exploit additional data sources as the national freight data program develops. New data sources may emerge in the future, but the committee identified two current opportunities as potentially promising—security data and passive data collection technologies.

Security Data

Concerns over national security may drive more timely and efficient collection of freight transportation data, including real-time data on goods movements and more detailed information on the nature and value of shipments. Much of this information could be useful for modeling and planning applications and for identifying opportunities to improve capacity utilization. However, the extent to which such security data will be made available for nonsecurity applications is unclear. There is even concern in some quarters that certain data currently available to the public may no longer be generally accessible because of their potential to undermine national security.

Regardless of the unanswered questions about access to security data, the committee believes that the national freight data program could provide the Department of Homeland Security with important information on freight movements. In particular, establishing a picture of normal freight flows would be valuable as a baseline against which to identify anomalies associated with possible security threats. In the committee’s view, there are mutual benefits for BTS and the Department of Homeland Security in working together to ensure that (a) security data feed

into the national freight data framework as far as possible within disclosure constraints and (b) the framework is designed to support security-related data needs.

Passive Data Collection

As discussed in the earlier section on the freight informatics initiative, the national freight data program will need to take advantage of nonsurvey data streams. Research will be required to investigate

-

Opportunities offered by new technology for low-cost passive data collection; and

-

Methods for sampling and processing the large quantities of data generated by monitoring and control systems that function 24 hours per day, 7 days per week.

For example, the tracking of electronic transmitters on shipping containers may result in low-cost, high-quality data, but new data sampling and processing strategies will be required to make the most effective use of such large quantities of information.

Opportunities have already been identified for using ITS data for a much wider range of applications than originally anticipated (see, for example, BTS 1998 and Margiotta 1998). Most ITS systems are designed to manage day-to-day or minute-to-minute conditions, and many of the data collected for these monitoring and control purposes are not saved. If ITS data are to be used in populating a national freight database, procedures for data integration and archiving will be required. Legal issues, privacy concerns, and limitations on the use of proprietary data will also need to be addressed. In the longer term, the possibility of developing ITS further to meet specific data collection needs may merit investigation.

The involvement of data providers in developing and implementing new data collection methods is likely to be important to the ultimate success of such efforts. For example, the trucking industry will need to be involved in discussions about the possible collection of data from Global Positioning System–based truck-tracking systems to ensure that proposed approaches are not only technically feasible but also compatible with normal operational practices.

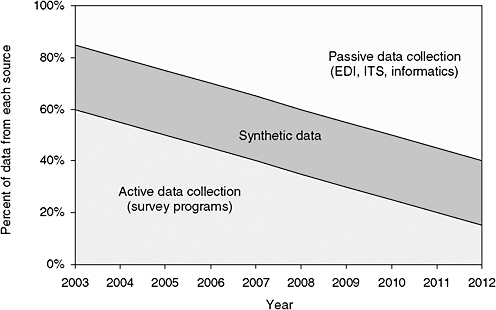

The committee recognizes that transitioning to passive data collection is “not a panacea” (BTS 1998, 18). Setup costs may be high, and the availability of continuous data streams will necessitate innovation in data management and processing. Nevertheless, passive data collection technologies are developing rapidly in coverage and sophistication and have the potential to generate large amounts of useful, high-quality data at low cost. Therefore, the committee anticipates that passive data collection is likely to increasingly replace active data collection (i.e., surveys) as the preferred method for populating the national freight database. For example, as ITS and EDI data become more widespread, traditional surveys are likely to become less important as sources of freight transportation data. The changing role of active and passive data collection approaches is illustrated schematically in Figure 3-2.8

The relative importance of active and passive data collection methods is likely to vary across modes of transportation as different modes embrace new technologies in different ways and on different schedules. For example, rail and marine carriers are already fairly advanced compared with other modes in implementing EDI. Thus, EDI may provide useful data for these modes in the relatively short term but may not capture a representative sample of freight movements by all modes of transportation for some years to come.

Figure 3-2 is also likely to look somewhat different for different data items. For example, because current truck detection systems can provide vehicle counts and information on vehicle type and speed, passive data collection could provide a high percentage of such data in the near term. However, these detection systems cannot determine the commodity being carried, so such information will need to be collected by active means, such as roadside surveys, pending the development of more sophisticated detector technology.

In the committee’s view, a phased approach to exploring the potential benefits of EDI and other electronic data streams offers important advantages. Useful data may be obtained in the relatively short term, and the lessons learned can be applied in subsequent development—for example, as other modes adopt EDI or as sensors used in passive data collection devices become more sophisticated.

|

8 |

Figure 3-2 is identical to Figure A-2 of Appendix A. |

Figure 3-2 Schematic representation of the roles of various data sources over time. Source: A paper prepared for the committee by R. Donnelly (Appendix A).

Confidentiality

The need to safeguard the confidentiality of data providers—and in particular to protect commercially sensitive information—will be critical in determining how data in the national freight database are made available to the public. Federal agencies such as the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection and the Census Bureau already collect data that could be useful for transportation analysts, modelers, and planners. However, legal limitations protecting the confidentiality of individual establishments prevent the release of raw data on freight movements and shape the presentation of data released to the public. These limitations are essential to obtaining the cooperation of data providers, without whose input survey programs such as the CFS would not be possible.

To meet the needs of users, particularly at state and local levels, the national freight data framework is intended to provide opportunities for improving the geographic resolution and level of commodity detail of freight data. However, a lack of accompanying measures to safeguard the

competitive position of individual firms and protect the confidentiality of data providers would be a fatal flaw in any efforts to implement the framework. Therefore, the committee considers it essential that a research effort to examine options for ensuring the necessary levels of confidentiality be initiated as one of the first steps toward implementation of the framework. Data providers will need to be involved in discussions of confidentiality requirements to ensure that proposed approaches address their concerns.

Research into confidentiality protection is likely to focus on a variety of models already in use or proposed. For example, limited data from the Rail Waybill Sample are available in a public use file, but more detailed information can be provided to certain parties upon approval by the Surface Transportation Board.9 For example, data may be provided to a contractor who has been asked to prepare investment advice for private-sector clients, but the clients themselves do not have access to the raw data. A particularly interesting model from the perspective of the national freight database is the hierarchical access system being developed for the ITDS. The ITDS will distribute standard data to federal agencies, but each agency will receive only information relevant to its mission.10 In the case of the national freight database, such varying levels of access to the data could eventually be provided through an interactive database system.

Other possible research areas include the application of disclosure limitation methods (see, for example, NRC 1993) and ways of protecting the confidentiality of items in electronic data streams being mined for passive data collection.11

Roles of Public and Private Sectors

Implementation of the proposed national freight data program will require the participation of a variety of public- and private-sector organizations at various levels. The former group will include federal agencies,

|

9 |

Access to nonpublic use rail waybill data is automatically granted to state governments. Access is granted to other parties on a need-to-know basis. |

|

10 |

ITDS Background (www.itds.treas.gov/itdsovr.html). |

|

11 |

In February 2003, BTS inaugurated a series of seminars to discuss confidentiality and access issues. Further details are available on the agency’s website (www.bts.gov/confidentiality_seminar_series/index.html). |

state departments of transportation (DOTs), MPOs, and local jurisdictions. The latter will include consulting companies, representatives of different modes of transportation, shippers, receivers, third-party logistics companies, and academic researchers. Since much of the nation’s freight transportation infrastructure is privately owned and almost all freight is carried by private firms, industry involvement will be critical to the success of the national freight data program.

In view of the diverse participation, broad scope, and complexity of the proposed program, the committee believes that federal government leadership will be needed to provide a key link among participants and to coordinate their activities. Federal government leadership does not imply that the federal government should bear the full financial burden of the national freight data program. For example, the Canadian NRS is coordinated at the federal level by Transport Canada but involves cost sharing with DOTs in the Canadian provinces and U.S. border states. The provincial DOTs are responsible for all data collection and related quality assurance. For both the 1995 and the 1999 NRS, a memorandum of understanding between Transport Canada and the provincial DOTs addressed areas such as study objectives, the federal formula for cost sharing, survey design, standardization of data collection processes, and data processing and dissemination. Similar approaches aimed at sharing costs and responsibilities among participants in the proposed national freight data program may merit investigation.

The freight data business plan presented in Appendix A suggests that BTS should be responsible for coordinating data collection activities to populate the national freight database; other organizations (private sector, state DOTs, MPOs, carriers, etc.) should be responsible for the collection and synthesis of supplemental data. The committee agrees in principle with this broad division of responsibilities between the federal government and other parties, although it recognizes that the detailed assignment of responsibilities will need to be worked out as part of the process of implementing a national freight data framework.

Experience with national surveys such as the CFS indicates the value of federal government involvement in providing transparent “core” data that are widely used by many different groups for a variety of purposes. For example, CFS data are used by the private sector to develop value-added data products, such as the Transearch database from Reebie

Associates and customized state and local databases constructed by consultants for specialized studies. The committee believes that the collection of specialized data is generally better left to organizations outside the federal government but considers it important for the national freight data framework to facilitate the linkage of such supplemental data to the national freight database.

Implementation of the national freight data framework will provide opportunities for various organizations to build on their strengths and experience in areas such as survey design, data collection, and data analysis. For example, a federal statistical agency such as BTS could play a key role in researching new sampling strategies for passive data collection systems and in developing standard survey methodologies to guide supplemental data collection efforts. Similarly, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and a number of private-sector organizations have developed expertise in data fusion through their work on the FHWA Freight Analysis Framework policy analysis tool. This expertise could be valuable both in developing the national freight database and in combining national and supplemental data for specialized applications.

The proposed framework includes a feedback loop from data users to the freight data advisory committee. This feature is intended to encourage ongoing dialogue between the advisory committee and data users to inform development and refinement of the national freight data program. A variety of feedback mechanisms will likely be needed to accommodate the diverse data users. Options include a feedback button on a website that allows users to send comments by e-mail, as in the case of the Vehicle Inventory and Use Survey, and meetings to facilitate the interchange of ideas among users and those responsible for survey development and design. The committee envisages the private sector playing a particularly valuable role in providing feedback, given its importance to the transportation enterprise as a whole and the underlying need to ensure confidentiality within the national freight data program.

A number of private-sector organizations currently provide freight data to meet specific client needs. The committee envisages that activities of this type will continue within the broad context of the national freight data program, which will need to recognize the private-sector role in selling value-added data to meet client requirements. In some instances, these data may be less transparent than those in the national

freight database; for example, different firms may fuse data sets differently using proprietary techniques for specific applications.

Implementation of the national freight data framework will require careful consideration of the roles of public- and private-sector parties in data fusion and synthesis to ensure that the desired levels of transparency are maintained and that users have access to unambiguous information on data reliability. Figure 3-1 indicates that it will be necessary to fuse data from the freight informatics initiative with survey data to populate the national freight database. This fusion process may be complicated by two factors. First, some of the freight informatics data—ITS data, for example—may not represent a random sample. Therefore, it will be necessary to develop statistical methods for fusing survey data collected from a random sample of respondents with nonrandom “informatics” data. Second, some of the data may not be collected by federal government agencies. When fusing such data with data from federal government surveys, it will be important to ensure that the sources and reliability of the resulting data are clearly reported. Under certain circumstances, private-sector groups could decide to follow the federal government lead in disclosing more information about the origin and reliability of their proprietary data. However, the extent of any such disclosure is difficult to anticipate. Thus, conferring the imprimatur of the federal government on fused data from a combination of federal and nonfederal sources could be potentially misleading to users whose expectations for federal government data are based on experience with the CFS and similar surveys. In the committee’s view, the public- and private-sector roles in a variety of data fusion activities merit further discussion.

Figure 3-1 also suggests that data synthesis should be the responsibility of parties outside of the federal government. Such data synthesis is a very different exercise from the data imputation performed during the analysis of raw survey data.12 In the committee’s opinion, there may be benefits in different groups making different assumptions and using different methods to obtain results aimed at meeting diverse user needs. As

noted earlier, the private sector has traditionally played an important role in developing data sets to meet the specialized needs of a range of users.

In the committee’s view, detailed definition of the public- and private-sector roles in implementing the data framework would be premature at this conceptual stage of the national freight data program. For example, decisions about strategies for protecting the confidentiality of data providers will be important in determining who has access to what data. Levels of data access will, in turn, largely determine who is in a position to undertake data-processing activities requiring access to survey microdata. Some data providers would like to see data stripped of any identifiers before being given to a regulatory agency such as the U.S. Department of Transportation. If implemented, this approach would have important implications for the development and maintenance of the national freight database.

NEXT STEPS

In the committee’s view, the conceptual plan for a national freight data program presented in Appendix A is a goal toward which BTS and others should aspire in seeking to respond to the recommendations of the 2001 Saratoga Springs conference. The committee recognizes that achieving the desired objective—a comprehensive picture of goods movement in North America—will take time and require considerable effort and resources. It is apparent from the preceding discussion that implementation of a national freight data framework will require careful analyses of various options to map out an appropriate strategy. Many technical and institutional issues will require investigation, and program planning, development, and management capabilities will be needed to help ensure the necessary continuity of effort. The committee’s recommendations address the initial programmatic and technical steps required to move forward with the implementation of a national freight data program.

REFERENCES

Abbreviations

BTS Bureau of Transportation Statistics

FHWA Federal Highway Administration

NRC National Research Council

BTS. 1998. Transportation Statistics Beyond ISTEA: Critical Gaps and Strategic Responses. BTS98-A-01. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

Census Bureau. 2001. Meeting 21st Century Demographic Data Needs— Implementing the American Community Survey. Report 1: Demonstrating Operational Feasibility. www.census.gov/acs/www/Downloads/Report01.pdf.

FHWA. 2002. The Freight Story: A National Perspective on Enhancing Freight Transportation. FHWA-OP-03-004. U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, D.C.

Margiotta, R. 1998. ITS as a Data Resource: Preliminary Requirements for a User Service. Office of Highway Policy Information, Federal Highway Administration. www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/its/itspage.htm.

Meyburg, A. H., and J. R. Mbwana (eds.). 2002. Conference Synthesis: Data Needs in the Changing World of Logistics and Freight Transportation. New York State Department of Transportation, Albany. www.dot.state.ny.us/ttss/conference/synthesis.pdf.

NRC. 1993. Private Lives and Public Policies: Confidentiality and Accessibility of Government Statistics. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Southworth, F. 1999. The National Intermodal Transportation Data Base: Personal and Goods Movement Components (draft). Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tenn.