4

Interventions Aimed at Illegal Firearm Acquisition

Firearms are bought and sold inmarkets, both formal and informal. To some observers this suggests that one method for reducing the burden of firearm injury is to intervene in these markets so as to make it more expensive, inconvenient, or legally risky to obtain firearms for criminal use. As guns become more expensive to acquire or hold, it is hypothesized that criminals will reduce the percentage of their criminal careers in which they are in possession of a gun. However, the pervasiveness of guns and the variety of legal and illegal means of acquiring them suggests the difficulty of keeping firearms from people barred by law from possessing them. The goals of this chapter are to provide a systematic analytic framework linking interventions to the outcomes of interest and to describe what is known about the effectiveness of those interventions. We also suggest a research agenda that addresses the major unanswered questions.

Market-based interventions intended to reduce criminal access to guns include taxes on weapons and ammunition, tougher regulation of federal firearm licensees, limits on the number of firearms that can be purchased in a given time period, gun bans, gun buy-backs, and enforcement of laws against illegal gun buyers or sellers. Other interventions that may have market effects—for example, storage requirements (such as trigger locks or the placement of firearms in secure containers) and mandating new technologies that personalize guns so only lawful owners can fire them—are dealt with in detail elsewhere in the report. While these new technologies may make new guns less attractive relative to older secondhand guns and thus reduce the attractiveness of guns in aggregate to offenders, the potential market effects are probably secondary to other mechanisms by which

these interventions may lower firearms injuries, such as preventing children from accidentally hurting themselves or others (see Chapter 8).

Little is known about the potential effectiveness of a market-based approach to reducing criminal access to firearms. Arguments for and against such an approach are based largely on speculation rather than research evidence. There is very little of an analytic or evaluative nature currently available in the literature on market interventions. Even on most descriptive topics (e.g., gun ownership patterns, types of guns used in crimes), there are only a few studies, often not well connected, that have been adequately summarized in existing papers (e.g., Braga et al., 2002; Hahn et al., 2005).

We begin with a brief discussion of legal and illegal firearms commerce, followed by a summary of what is known about the methods by which offenders acquire guns. We then present an analytic framework to understand the effects of specific interventions on gun markets. The next section reviews the literature evaluating various interventions. The final section presents the committee’s views about high-priority research activities. The relationship of firearms acquisition and markets to suicide is quite different and is discussed in the chapter on suicide.

We note that the interventions discussed here may impose costs on legitimate users of firearms. A waiting period law inconveniences hunters and others who use firearms in legitimate fashion. In addition to delays, the system may generate errors, causing unnecessary embarrassment or worse. Some interventions putatively have no such effects and may even facilitate the activities of legitimate owners; for example, gun buy-backs can only help by providing another outlet for individuals wishing to dispose of existing weapons with minimal inconvenience. No research has explored these effects, although they may be important in forming attitudes toward gun control proposals.

HOW OFFENDERS OBTAIN FIREARMS

Legal and Illegal Firearms Commerce

In the United States, there are some 258 million privately owned firearms, including nearly 70 to 90 million handguns (Police Foundation, 1996; see also Table 3-2). Some 4.5 million new firearms, including about 2 million handguns (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000b) and about 2 million secondhand guns, are sold each year in the United States (Police Foundation, 1996). Legal firearms commerce consists of transactions made in the primary firearms market and in the largely unregulated secondary firearms market. Acquisitions (other than theft) of new and secondhand firearms from federal firearms licensees (FFLs), whether conducted properly or not, form the primary market for firearms (Cook et al.,

1995). Retail gun stores sell both new and secondhand firearms and, in this regard, resemble automobile sales lots. FFLs are required to ask for identification from all prospective gun buyers and to have them sign a form indicating that they are not prohibited from acquiring a firearm; the FFL must also initiate a criminal history background check of all would-be purchasers. FFLs are also required to maintain records of all firearms transactions, report multiple sales and stolen firearms to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF), provide transaction records upon request to BATF; when they go out of business, they are required to transfer their records to BATF.

A privately owned gun can be transferred in a wide variety of ways not involving FFLs, such as through classified ads in newspapers, gun magazines, and at gun shows (which include both licensed and unlicensed dealers). Transfers of secondhand firearms by unlicensed individuals form the secondary market, for which federal law does not require transaction records or criminal background checks of prospective gun buyers (Cook et al., 1995). Using household survey data, Cook and Ludwig (1997) estimate that about 2 million transactions per year (30-40 percent of all gun transactions) occur in the secondary market. Primary and secondary firearms markets are closely linked because many buyers move from one to the other depending on relative prices and other terms of the transaction (Cook and Leitzel, 1996).

Since states vary greatly in their requirements on secondary firearms market transfers (see, e.g., Peters, 2000), another way to think about firearms commerce is to distinguish between regulated and unregulated transfers. In Massachusetts, for example, all firearms transfers must be reported to the state police, and secondary markets can be regulated through inspection of these transfer records (Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 140). In neighboring New Hampshire, however, sales of guns by private citizens are not recorded, and even legitimate transfers in the secondary market cannot be monitored. In this report we use the primary/secondary distinction because it is standard, but regulation is probably the critical distinguishing feature.

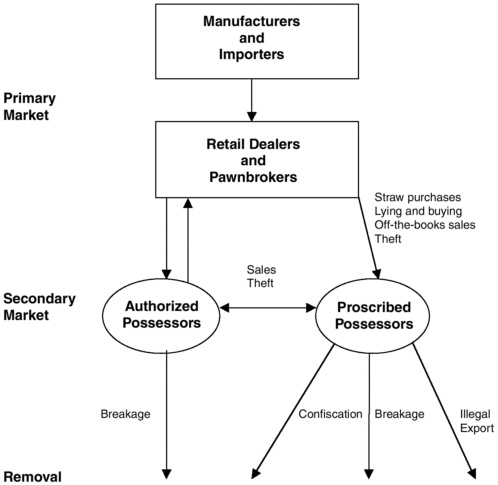

Figure 4-1 presents a conceptual scheme of the flow of firearms to prohibited persons developed by Braga and his colleagues (2002). Through theft, firearms can be diverted to criminals and juveniles at any stage of commerce. Guns can be stolen from manufacturers, importers, distributors, licensed dealers, and private citizens. Cook et al. (1995) estimated that some 500,000 guns are stolen each year. This estimate, derived from National Crime Victimization Survey data for the years 1987 to 1992, suggests that 340,700 thefts occurred annually in which one or more guns were stolen; separate data from North Carolina suggest that on average 1.5 guns are stolen per theft (Cook et al., 1995). This figure is also consistent with a

FIGURE 4-1 Firearms flows.

SOURCE: Braga et al. (2002).

similar estimate calculated for the Police Foundation (Cook and Ludwig, 1997), which used data from a telephone survey of a nationally representative sample of 2,568 adults in which those who were gun owners reported firearms theft and the number of firearms stolen per theft. Braga et al. (2002) also identify three broad mechanisms through which criminal consumers acquire firearms from licensees without theft: straw purchase, “lying and buying,” and buying from a dealer who is willing to ignore regulations. A straw purchase occurs when the actual buyer, typically someone who is too young or otherwise proscribed, uses another person to execute the paperwork. Lying and buying refers to prohibited persons (e.g., felons and juveniles ) who purchase firearms directly by showing false identification and lying about their status. And in some cases the seller is knowingly

involved and may disguise the illegal transaction by falsifying the paper record of sale or reporting the guns as stolen.

The available research evidence suggests that gun-using criminals go through a number of guns during the course of their short careers. The population of active street criminals is characterized by brief careers (typically 5 to 10 years) and many interruptions through incarceration and injury (National Research Council, 1986). Each year a substantial fraction of current offenders are released from prison and may have to acquire new weapons in order to continue their criminal career; others will have just begun their careers and must obtain guns from somewhere. Survey research on criminally active populations suggests that gun offenders buy, steal, borrow, sell, and otherwise exchange guns quite frequently (Wright and Rossi, 1994; Sheley and Wright, 1993).

Young offenders have been noted as active in illegal markets both as sellers and buyers of guns through their informal networks of family, friends, and street sources. Using data from self-administered questionnaires completed by 835 male inmates in six correctional facilities in four states between November 1990 and February 1991, Sheley and Wright (1993) found that 86 percent of juvenile inmates had owned at least one firearm at some time in their lives, 51 percent reported having personally dealt with many guns before being incarcerated, and 70 percent felt that they could get a gun “with no trouble at all” upon release. Wright and Rossi (1994) found that 75 percent of incarcerated adult felons had owned at least one firearm at some time in their lives and, for those who did report ownership, the average number of guns owned prior to their current incarceration was approximately six. For incarcerated felons who reported stealing at least one gun, 90 percent also reported that they had sold or traded a stolen gun at least once in the past, and 37 percent had done so many times.

It is also important to recognize that guns have value in exchange as well as in use. Based on interviews with youth offenders, Cook and his colleagues (1995) suggest that guns were valuable commodities for youth to trade for services, money, drugs, or other items such as video games, VCRs, phones, and fax machines.

Guns are not costly when compared with other durable goods but may constitute a large asset in the portfolio of drug users or of youth. The retail prices of guns vary greatly based on the type, manufacturer, model, caliber, and age. For example, the suggested retail price of a new high-quality 9mm semiautomatic pistol is about $700, while a secondhand low-quality one can retail for as little as $50 (Fjestad, 2001). The proximate source of a gun can also influence its price for prohibited persons. Sheley and Wright’s (1995) survey research suggests that juveniles paid less for guns acquired from informal and street sources than for guns acquired through normal retail outlets, such as gun stores and pawnshops: 61 percent of the juvenile

inmates and 73 percent of the high school students who acquired their guns from a retail outlet paid more than $100, while only 30 percent of the juvenile inmates and 17 percent of the high school students who acquired their most recent gun from an informal or street source paid more than $100 (Sheley and Wright, 1995:49). We do not know whether this is driven by differences in the quality of the guns purchased or in the costs of distribution in the two sectors.

Gun Sources

There are three main types of evidence on the origins of guns for criminals and juveniles: survey research, BATF firearms trace data, and BATF firearms investigation data. Each provides different insights into the means by which offenders acquire firearms.

Survey Research

A number of inmate surveys have documented the wide variety of sources of guns available to criminals and youth. Table 4-1 summarizes some of the basic findings from three of the most widely cited of these surveys. Precise patterns are sometimes difficult to discern because different definitions and questions are used to elicit similar information. Nevertheless, survey research has documented a wide variety of sources of guns and methods of firearm acquisition used by criminals and youth. Guns referenced in these surveys come from a variety of sources, including family members, friends, the black market, and direct theft.

Wright and Rossi’s (1994) 1992 survey of 1,874 convicted felons serving time in 11 prisons in 10 states throughout the United States, for example, revealed a complex market of both formal and informal transactions, cash and noncash exchange, and new and used handguns. Felons reported acquiring a majority of their guns from nonretail, informal sources. Only 21 percent of the respondents obtained the handgun from a retail outlet, with other sources including family and friends (44 percent) and the street (that is, the black market), drug dealers, and fences (26 percent). Moreover, the majority of handguns were not purchased with cash. Of the surveyed felons, 43 percent acquired their most recent handgun through a cash purchase, while 32 percent stole their most recent handgun. The remainder acquired their most recent handgun by renting or borrowing it, as a gift, or through a trade. Finally, almost two-thirds of the most recent handguns acquired by felons were reported as used guns, and one-third were reported as new guns. Illicit firearms markets dealt primarily in secondhand guns and constituted largely an in-state, rather than out-of-state, market.

TABLE 4-1 Sources and Method of Handgun Acquisition by Criminals

|

Study |

Measure |

Method of Firearm Acquisition as Reported by Prison Inmates |

Source of Firearm as Reported by Prison Inmates |

|

Bureau of Justice Statistics (1993) |

Handgun possessed by inmate |

27% retail purchase 9% direct theft |

31% family/friends 28% black market/fence 27% retail outlet |

|

Wright and Rossi (1994) |

Most recent handgun—incarcerated felons |

43% cash purchase 32% direct theft 24% rent/borrow, trade, or gift Estimated 40-70% directly or indirectly through theft |

44% family and friends 26% black market/fence 21% retail outlet |

|

Sheley and Wright (1993) |

Most recent handgun—incarcerated juveniles |

32% straw purchase 12% theft |

90% from friend, family, street, drug dealer, drug addict, house or car |

Results from a 1991 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) survey of some 2,280 handgun-using state prison inmates support Wright and Rossi’s observation that the illicit firearms market exploited by criminals is heavily dominated by informal, off-the-record transactions, either with friends and family or with various street sources (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1993). The 1991 survey found that only 27 percent of the inmates who used a handgun in crime that led to their incarceration reported they obtained the handgun by purchase from a retail outlet. In contrast to the Wright and Rossi (1994) findings, the BJS survey found that only 9 percent of inmates who used a handgun in a crime had stolen it. More recently, Decker and colleagues’ (1997) analysis of arrestee interview data (i.e., the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Survey) revealed that 13 percent of arrestees admitted to having a stolen gun. Among juvenile males, one-quarter admitted to theft of a gun (Decker et al., 1997).

Sheley and Wright’s (1993) survey of high school students and incarcerated juveniles suggested that informal sources of guns were even more important to juveniles.1 More than 90 percent of incarcerated juveniles obtained their most recent handgun from a friend, a family member, the street, a drug dealer, or a drug addict, or by taking it from a house or car (Sheley and Wright, 1993:6). Sheley and Wright (1995) found that 12 percent of juvenile inmates had obtained their most recent handgun by theft and 32 percent of juvenile inmates had asked someone, typically a friend or family member, to purchase a gun for them in a gun shop, pawnshop, or other retail outlet. When juveniles sold or traded their guns, they generally did so within the same network from which they obtained them—family members, friends, and street sources (Sheley and Wright, 1995).

BATF Firearms Trace Data

BATF firearms trace data, described in Chapter 3, have been used to document that firearms recovered by law enforcement have characteristics suggesting they were illegally diverted from legitimate firearms commerce to criminals and juveniles (see, e.g., Zimring, 1976; Kennedy et al., 1996; Wachtel, 1998; Cook and Braga, 2001). Trace data, reflecting firearms recovered by police and other law enforcement agencies, have revealed that a noteworthy proportion of guns had a “time to crime” (the length of time from the first retail sale to recovery by the police) of a few months or a few years. For example, Cook and Braga (2001) report that 32 percent of traceable handguns recovered in 38 cities participating in BATF’s Youth

Crime Gun Interdiction Initiative (YCGII) were less than 3 years old. Cook and Braga (2001) also report that only 18 percent of these new guns were recovered in the possession of the first retail purchaser, suggesting that many of these guns were quickly diverted to criminal hands. Recovered crime guns are relatively new when compared with guns in public circulation. Pierce et al. (2001) found that guns manufactured between 1996 and 1998 represented about 14 percent of guns in private hands, but they accounted for 34 percent of traced crime guns recovered in 1999.

Wright and Rossi (1994) found that criminals typically use guns from within-state sources, whereas the 1999 YCGII trace reports suggest that the percentage of crime guns imported from out of state is closely linked to the stringency of local firearm controls. While 62 percent of traced YCGII firearms were first purchased from licensed dealers in the state in which the guns were recovered (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000c), this fraction was appreciably lower in northeastern cities with tight control—for example, Boston, New York, and Jersey City—where less than half of the traceable firearms were sold at retail within the state. A noteworthy number of firearms originated from southern states with less restrictive legislation, for example, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Florida (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000c).

Moreover, by examining the time-to-crime of out-of-state handguns in the trace data, Cook and Braga (2001) concluded that the process by which such handguns reach criminals in these tight-control cities is not one of gradual diffusion moving with interstate migrants (as suggested by Blackman, 1997-1998, and Kleck, 1999); rather, the handguns that make it into these cities are imported directly after the out-of-state retail sale. In contrast, Birmingham (AL), Gary (IN), Houston (TX), Miami (FL), New Orleans (LA), and San Antonio (TX), had at least 80 percent of their firearms first sold at retail in the state in which the city was located (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000c). Kleck (1999) attempts to explain the interstate movement of crime guns by simply observing that, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 9.4 percent of the United States population moved their residence across state lines between 1985 and 1990. These migration patterns, however, do not necessarily explain the big differences in import and export patterns across source and destination states as well as the overrepresentation of new guns that show up in tight-control cities from other loose-control states.

BATF Investigation Data

While analyses of BATF trace data can document characteristics of crime guns that suggest illegal diversions from legitimate firearms commerce, trace data analyses cannot describe the illegal pathways through

TABLE 4-2 Volume of Firearms Diverted Through Trafficking Channels

|

Source |

N(%) |

Total Guns |

Mean |

Median |

|

Firearms trafficked by straw purchaser or straw purchasing ring |

695 (47%) |

25,741 |

37.0 |

14 |

|

Trafficking in firearms by unregulated private sellersa |

301 (20%) |

22,508 |

74.8 |

10 |

|

Trafficking in firearms at gun shows and flea markets |

198 (13%) |

25,862 |

130.6 |

40 |

|

Trafficking in firearms stolen from federal firearms licensees |

209 (14%) |

6,084 |

29.1 |

18 |

|

Trafficking in firearms stolen from residence |

154 (10%) |

3,306 |

21.5 |

7 |

|

Firearms trafficked by federal firearms licensees, including pawnbroker |

114 (8%) |

40,365 |

354.1 |

42 |

|

Trafficking in firearms stolen from common carrier |

31 (2%) |

2,062 |

66.5 |

16 |

|

aAs distinct from straw purchasers and other traffickers. NOTE: N = 1,470 investigations. Since firearms may be trafficked along multiple channels, an investigation may be included in more than one category. This table excludes 60 investigations from the total pool of 1,530 in which the total number of trafficked firearms was unknown. SOURCE: Adapted from Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (2000d). |

||||

which crime guns travel from legal commerce to its ultimate recovery by law enforcement. BATF also conducts numerous investigations both in the course of monitoring FFL and distributor compliance with regulations and following detection of gun trafficking offenses. Analyses of BATF firearms trafficking investigation data provide insights on the workings of illegal firearms markets (see, e.g., Moore, 1981; Wachtel, 1998). To date, the most representative look at firearms trafficking through a comprehensive review of investigation data was completed by BATF in 2000. This study examined all 1,530 investigations made between July 1996 and December 1998 by BATF special agents in all BATF field divisions in the United States2 (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000d). They involved the diversion of more than 84,000 guns. As indicated in Table 4-2, the study revealed a variety of pathways through which guns were illegally diverted to criminals and juveniles.

The BATF study found that 43 percent of the trafficking investigations involved the illegal diversion of 10 guns or fewer but confirmed the existence of large trafficking operations, including two cases involving the diversion of over 10,000 guns. Corrupt FFLs accounted for only 9 percent of the trafficking investigations but more than half of the guns diverted in the pool of investigations. Violations by FFLs in these investigations included “off paper” sales, false entries in record books, and transfers to prohibited persons. Nearly half of the investigations involved firearms trafficked by straw purchasers, either directly or indirectly. Trafficking investigations involving straw purchasers averaged a relatively small number of firearms per investigation but collectively accounted for 26,000 guns. Firearms were diverted by traffickers at gun shows and flea markets in 14 percent of the investigations, and firearms stolen from FFLs, residences, and common carriers were involved in more than a quarter of the investigations.

Interpreting the Data

Braga et al. (2002) suggest that the three sources of data on illegal gun markets are not directly comparable but broadly compatible. Each data source has its own inherent limitations and, as such, it is difficult to credit the insights provided by one source over another source.

None of the three sources of data contradicts the hypothesis that stolen guns and informal transfers (as opposed to transfers from legitimate sources) predominate in supplying criminals and juveniles with guns. However, they also clearly suggest that licensed dealers play an important role and that the illegal diversion of firearms from legitimate commerce is a problem. In their review of these three sources of data, Braga and his colleagues (2002) suggest that, in the parlance of environmental regulation, illegal gun markets consist of both “point sources”—ongoing diversions through scofflaw dealers and trafficking rings—and “diffuse sources”—acquisitions through theft and informal voluntary sales. As in the case of pollution, both point sources and diffuse sources are important (see also Cook and Braga, 2001). Braga and his colleagues (2002) also speculate that the mix of point and diffuse sources differs across jurisdictions depending on the density of gun ownership and the strictness of gun controls.

ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

General Model

Real interventions in gun markets tend to target particular types of firearms or sources. If policy raises the difficulty (cost, time, risk) of obtaining a particular type of gun or using a particular type of source, the effect

might be mitigated by criminals’ substitution across types of guns or sources. The following framework is helpful for organizing what is known, and what we would like to know, about whether access interventions can reduce harms from criminal gun use.

There are many types of guns; the term “type” encompasses both the literal firearm type (e.g., handguns versus long guns) and the source by which it is acquired (e.g., retail purchase, private sale, theft, loan, and other types of firearm transfers).3 Furthermore, there are many types of individuals (legal possessors, juveniles, convicted felons and other persons prohibited from legal gun possession). Restrictions aim at reducing firearm possession or use by some of those groups. For analyzing the effects of these restrictions, consumer demand theory provides a useful conceptual framework, in which the use of each type of gun by each type of individual depends on the total cost that individual incurs in acquiring or retaining that gun. This generates a specific volume of use (possession or purchase) by each type of individual for each type of weapon. When the difficulty felons face in acquiring new guns rises, for example because of a targeted intervention, we assume that new gun use will decline among felons; whether that decline is substantial can be determined only empirically. Use of other kinds of guns may rise.

We use the term “cost” as broader than the money required for purchase of the item. Nonmonetary costs may be particularly important for gun acquisition by offenders, compared with purchases of unregulated legal goods; these costs include the time required to locate a reliable source or obtain information about prices, the risk of arrest by police (and sanction by a court), and the risk of violence by the seller. These are potentially important in any illicit market and have received some attention in the context of drug markets (Caulkins, 1998; Moore, 1973).

To make clear how this framework operates, consider an intervention that raises the costs criminals face to obtain new guns. The direct or “own” effect of this intervention is to reduce criminals’ demand for new guns. Yet this is not the end of the story. The total effect of the policy intervention is the sum of the “own effect” and a “cross-effect” reflecting criminals’ substitution of used guns for new ones as new guns become more costly. Even if the own effect is negative, the cross-effect might be sufficiently positive to render the overall effect close to zero.

The patterns of substitution among sources may be different for different types of potential buyers. Adults without felony convictions or other disqualifications can presumably choose between buying new guns from retailers and used guns from legal private sellers. Juveniles, by contrast, cannot buy from retailers or law-abiding dealers in used guns. However, they can conceivably substitute by obtaining guns from a number of sources outside legal commerce, such as residential theft, informal transfers through their social networks, and scofflaw dealers; as one source becomes more difficult, youth may obtain more from another.

This framework is limited to an assessment of effects on the quantities of guns owned, which is not the final outcome of interest. Rather, it is crime or violence that ultimately interests policy makers. Whether changing the number and characteristics of firearms in the hands of persons of a given type increases harm is an additional question that requires different data and is considered at the end of the chapter.

We classify potential market interventions in two dimensions: market-targeted (primary or secondary) and supply or demand side programs. For example, consider police undercover purchases from unlicensed dealers. These aim to shift the supply curve in secondary markets by increasing the perceived risk of sale; dealers will be less willing to sell to unknown buyers and will charge a higher price when they do. Whether this has an influence on criminal possession of guns depends on many factors, such as the share of purchases that are made from nonintimate dealers and the price elasticity of demand (i.e., how much an increase in the price affects the purchase and retention of guns). Other interventions are focused on reducing demand, for example, taxes on FFL sales (primary market) and increasing sentences for purchasing from unlicensed dealers (secondary market).

Demand

What determines the demand for guns? Offenders acquire firearms for a variety of reasons: self-protection, a means for generating income, a source of esteem and self-respect, and a store of value. For example a rise in violence in a specific city may shift the demand curve up because of the increased return to self-protection. We assume that the demand for guns for criminal purposes is negatively related to the price and other costs of acquisition; there is no research on the elasticity with respect to either price or any other cost component that would allow quantification of the importance of this effect. Note that individuals make two kinds of acquisition decisions, active and passive; passive refers to holding rather than selling a valuable asset. Most market interventions aim only at the acquisition decision; retention is affected only indirectly, in that an increase in the value of a gun may lead to a greater willingness to sell to others.

Individual demand has an important time dimension to it, which makes inconvenience of acquisition a potentially valuable goal for an intervention. The value of a gun is partly situation-dependent; a perceived insult or opportunity to retaliate against a rival may make a firearm much more valuable if acquired now rather than in a few hours, when the opportunity or the passion has passed. Analytically and empirically that is a substantial complication; individuals are now characterized not only by their general risk of using a firearm for criminal purposes but also by their time-specific propensity of such use. This also allows for the possibility of positive effects from interventions that merely reduce the fraction of time an offender has a firearm.

Supply

The factors affecting the supply of firearms to offenders are comparably numerous. Guns used in crimes (crime guns) are obtained both from the existing stock in private hands (purchase in secondhand markets, theft, gifts) and from new production (sales by and thefts from FFLs, wholesalers, or manufacturers). In the aggregate these sources can be thought of as constituting a supply system; a higher money price will generate more guns for sale to high-risk individuals. Supply side interventions aim to shift the supply curve up, so that fewer guns are available at any given money price.

It may be useful to conceptualize each supply curve as independently determined. The factors that affect the costs of providing firearms through thefts (whether from households or stores) are likely to be distinct from those affecting provision of the same weapons through straw purchases. Raising penalties for stealing guns or expanding the burglary squad will raise the risk compensation (i.e., price) needed to induce burglars to undertake a given volume of gun theft. Those same measures are unlikely to have much effect on the risks faced in straw purchase transactions, which will be raised for example by tougher enforcement of FFL record-keeping requirements. While we will refer to a single supply curve for firearms to offenders, it is the sum of a number of components.

Markets may also be places; that is the guiding principle of much antidrug policing, since there are specific locations at which many sales occur on a continuing basis. It is unclear whether places are important for gun acquisition. Gun purchases are very rare events when compared with drug purchases; a few per year versus a few per week for those most active in the market (Koper and Reuter, 1996). The low frequency of gun purchases has two opposing effects. On one hand, it reduces the attraction to a seller of being in a specific place, since there will be a long period with no purchases but with potential police attention. On the other hand, buyers are less likely to be well informed because of the low rate of purchase and

may be willing to pay a substantial price premium to obtain a gun more rapidly, thus increasing the value of operating in a location that is known to be rich in firearms acquisition opportunities.

Gun shows are potential specific places where criminals acquire guns. Gun shows may be especially attractive venues for the illegal diversion of firearms due to the large number of shows per year, the size of the shows, the large volume of transactions, and the advertising and promotion of these events. Gun shows provide a venue for large numbers of secondary market sales by unlicensed dealers; they are exempted from the federal transaction requirements that apply to licensed dealers who also are vendors at these events. The Police Foundation (1996) estimated, from the National Survey of Private Gun Ownership, that gun shows were the place of acquisition of 3.9 percent of all guns and 4.5 percent of handguns. The 1991 BJS survey of state prison inmates suggests that less than 1 percent of handgun using inmates personally acquired their firearm at a gun show (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1993). However, these data did not determine whether a friend, family member, or street dealer purchased the gun for the inmate at a gun show. While it is not known what proportion of crime guns come from gun shows or what proportion of gun show dealers act criminally, research suggests that criminals do illegally acquire guns at these venues through unlicensed dealers, corrupt licensed dealers, and straw purchasers (Braga and Kennedy, 2000). Certain states specifically regulate firearms sales at gun shows; otherwise, there have been no systematic attempts to implement place-based interventions to disrupt illegal transactions at gun shows.

Note that the market is partly a metaphor. For example, many guns are acquired through nonmarket activities, gifts or loans from friends with no expectation of a specific payment in return. These may take place “in the shadow” of the market, so that the terms are influenced by the costs of acquiring guns in formal transactions; when guns are more expensive to acquire in the market, owners are more reluctant to lend them. However there is no empirical basis for assessing how close these links are. An additional complication is that guns are highly differentiated and there is no single price. No agency or researcher has systematically collected price data over a sufficient length of time to determine the correlation of prices across gun types over time and thus whether they are appropriately treated as a single market or even a set of linked markets.

Using the Framework

One value of this approach (demand, supply, and substitution) is in developing intermediate measures of whether an intervention might influence the desired outcome. For example, intensified police enforcement

against sellers in the informal market (through “buy-and-bust” stings), even though affecting the firearms market for offenders, may not be a large enough intervention to produce detectable changes in the levels of either violent crimes or violent crimes with firearms, given the noisiness of these time series and lags in final effects. However, if this enforcement has not affected the money price or the difficulty of acquisition in the secondary market, then it almost certainly has not had the intended effects; thus a cost measure provides a one-sided test. The ADAM (Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring) data system provided a potential source of such data at the local level.

Table 4-3 presents a list of hypothesized effects of the major interventions discussed in this chapter. This is more in the nature of a heuristic than a precise classification or prediction. It distinguishes between the two classes of markets and the two forms of acquisition cost (monetary and nonmonetary) in each market. Note again that the principal market for offenders is conceptualized as illegal diversions from retail outlets, such as convicted felons personally lying and buying or using false identification to acquire guns, straw purchasers illegally diverting legally purchased guns, and corrupt licensed dealers falsifying transaction paperwork or making off-the-book sales. The secondary market includes all other informal firearms transfers, such as direct theft, purchases of stolen guns from others, loans or gifts from friends and families, and unregulated sales among private sellers.

TABLE 4-3 Intermediate Effects of Market Interventions

SUBSTITUTION

Suppose for the sake of discussion that policy interventions can raise the difficulty faced by some individuals in obtaining some types of guns. The question of whether such interventions reduce gun use (or crime or violence) depends on how readily the potential buyers could substitute alternative weapons or sources for those targeted by policy.

In our framework, the existing studies, summarized in the section on how offenders obtain firearms, describe the distribution of guns across acquisition sources for a particular type of buyers (felons or youthful offenders). These surveys cannot provide an estimate of the total number of guns held by the population of offenders.

Although the studies are conducted on nonrandom convenience samples of inmates, they show fairly consistently that many guns are stolen or borrowed, rather than purchased in the primary market. Many guns are obtained through informal networks. The fact that criminals acquire guns from a variety of sources suggests substitution. Indeed, some (see, e.g., Kleck, 1999; Wright and Rossi, 1994; Sheley and Wright, 1995) have taken these studies to suggest that substitution possibilities are so pervasive that interventions cannot control the amount of gun use or ensuing harm. Some observers draw similar inferences from the fact that many guns are stolen from the large stock of guns available to steal.

Our framework, though simple, suggests that there are limits to what one can infer about substitution from these data. First, the existing studies combine survey responses of inmates from a variety of cities. The fact that inmates from various places, taken collectively, get their guns from different sources does not mean that any particular criminal or criminals in any particular city have ready access to all these alternatives. Cities may differ in terms of the sources of guns. Furthermore, even if persons of a particular type in a locale obtain their guns through different channels, this does not imply that each person has a variety of channels if deprived of the channel he or she currently uses.

Another finding in the literature concerns the vintage of guns used in crime. Vintage enters the framework through type: new and old guns may be seen as different types with particular policy relevance because there are different interventions for each type. In spite of the vast numbers of used guns that could be stolen and then transferred to criminals, the trace data suggest that a disproportionate fraction of crime guns are quite new, although, as noted in Chapter 2, it cannot be determined how well the trace data represent the total population of crime guns. In our framework, we can interpret this information to mean that criminals favor new guns over used guns, given current acquisition costs; this reflects in part the fact that new guns lack a potential liability from use in a previous crime that is unknown to the current purchaser. Again, it is only information on the

distribution of types of guns used by criminals. Since criminals use new guns, some observers have taken this information to indicate that interventions targeting new guns can reduce crime. This is a possible but not a necessary consequence. If both new and old guns are available to criminals, and criminals are observed using new guns, we can infer that criminals prefer new guns to old ones, given the respective prices and difficulties of obtaining the two types of guns. But this fact provides no information about whether criminals would substitute old guns for new ones if they faced increased difficulty of getting new ones.

That different criminals get their guns from a variety of sources—and that many guns used in crime are recent guns—provides little evidence about whether interventions would affect the volume of gun use. This is information about the types of guns used, not about the volume of, or harm caused by, guns. By itself, these findings are consistent with any level of substitution. Suppose that, when local rules are loose, some criminals get guns locally while others get them from elsewhere. The locale then adopts tight rules and suppose that all guns seized thereafter turn out to be nonlocal. That is consistent with either of two contradictory stories. In one, the restriction is totally effective and those who were purchasing local firearms can find none. In the other, there is full substitution; all the local buyers are able to find nonlocal sources without much increase in cost. Any inference requires information about the change in the tendency for the targeted type of individual to purchase other guns relative to those targeted with restrictions. In the language of our framework, we need to know the effects of the restriction on costs and of own costs and other prices on the tendencies for each type of person to buy guns.

INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE CRIMINAL ACCESS TO FIREARMS

This section summarizes the existing literature on the effects of different kind of access interventions. We do not include taxes on firearms or ammunition because there are no evaluations of either kind of tax.

Regulating Gun Dealers

As already noted, criminals can acquire guns in the primary market by personally making illegal purchases, arranging straw purchases, and by finding corrupt FFLs willing to ignore transfer laws. The available research evidence reveals that a very small number of FFLs generate a large number of crime gun traces (Pierce et al., 1995; Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000b). Assuming it is possible to categorize dealers by risk of diversion per weapon, this concentration of crime gun traces suggests an opportunity to reduce the illegal supply of firearms to criminals by focusing limited regulatory and investigative resources on the relatively small group

of high-risk dealers. In theory, this approach would increase the cost of guns to criminals by restricting their availability through retail outlets. However, in order for this approach to be effective in reducing gun violence, there must be limited substitution from regulated primary markets to unregulated secondary markets.

In their analysis of trace data contained in BATF’s Firearm Tracing System, Pierce et al. (1995) found that nearly half of all traces came back to only 0.4 percent of all licensed dealers. However, the concentration of trace data may simply reflect the very high concentration of firearms sales among FFLs. In California, the 13 percent of FFLs with more than 100 sales during 1996-1998 accounted for 88 percent of all sales (Wintemute, 2000). While handgun trace volume from 1998 was strongly correlated with handgun sales volume at the level of the individual dealer and highly concentrated among high-volume dealers, Wintemute (2000) also found that trace volume varied substantially among dealers with similar sales volumes, suggesting that guns sold by certain dealers were more at risk for generating crime guns than others. However, as Braga and his colleagues (2002) point out, Wintemute did not determine whether this variation was greater than could be explained by chance alone. It is possible that the variation of traces among dealers with similar trace volume was not significantly different from what would be expected from a normal distribution of crime gun traces among dealers.

The findings are important nonetheless. Even if only some high-volume dealers are high risk, the fact that most crime weapons come from high-volume dealers suggests that concentration of regulatory resources on this relatively small population may lead to more efficient enforcement, unless there is substitution across dealers by size category.

Due to concern that some FFLs were scofflaws who used their licenses to supply criminals with guns, the Clinton administration initiated a review of licensing procedures that led to their tightening (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000b). In 1993 and 1994, federal law was amended to provide more restrictive application requirements and a hefty increase in the licensing fee, from $30 to $200 for three years. After these provisions were put into place, the number of federal licensees declined steadily from 284,117 in 1992 to 103,942 in 1999 (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000b). With the elimination of some 180,000 dealers, BATF regulatory and enforcement resources became less thinly spread. In 2000, BATF conducted focused compliance inspections on dealers who had been uncooperative in response to trace requests and on FFLs who had 10 or more crime guns (regardless of time-to-crime) traced to them in 1999 (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000a). The inspections disclosed violations in about 75 percent of the 1,012 dealers inspected. While the majority of the discrepancies were resolved during the

inspection process, some 13,271 missing guns could not be accounted for by 202 licenses, and 16 FFLs each had more than 200 missing guns. More than half of the licensees had record-keeping violations only. The focused compliance inspections identified sales to more than 400 potential firearms traffickers and nearly 300 potentially prohibited persons, resulting in 691 referrals sent to BATF agents for further investigation (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000a). This reinforces the impression that a relatively small number of dealers systematically violate rules in ways that allow for leakage of guns to prohibited persons.

In a recent paper, Koper (2002) examined the effects of the nearly 70 percent reduction in FFLs following the 1993 and 1994 federal licensing reforms on the availability of guns to criminals. Using a data base of all active gun dealers in summer 1994 and the number of BATF gun traces to each dealer since 1990, Koper examined whether “dropout” dealers were more likely to be suppliers of crime guns than were “survivor” dealers. He concluded that it was not clear whether guns sold by the dropout dealers had a higher probability of being used in crime or moved into criminal channels more quickly when compared with active dealers. This study, however, used national BATF firearms trace data from 1990 through 1995, before the adoption of comprehensive tracing practices in most major cities and prior to BATF nationwide efforts to encourage law enforcement agencies to submit guns for tracing (Cook and Braga, 2001; Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000c). National trace data from this time period are not representative of guns recovered by law enforcement, so it is difficult to interpret the findings of Koper’s analysis of the impact of federal licensing reforms on the availability of guns to criminals.

Some states and localities have imposed additional regulations on gun dealers. In 1993, North Carolina found that only 23 percent of dealers also possessed its required state license (Cook et al., 1995). Noncomplying dealers were required to obtain a state license or forfeit their federal license. Alabama also identified FFLs who did not possess the required state license; 900 claimed not to know about the state requirements and obtained the license; another 900 reported that they were not currently engaged in the business of selling firearms; and 200 more could not be located (Cook et al., 1995). Alabama officials scheduled the licenses for these 1,100 dealers for cancellation. The Oakland (CA) Police Department worked with BATF to enforce a requirement for all licensed dealers to hold a local permit that required dealers to undergo screening and a criminal background check (Veen et al., 1997). This effort caused the number of license holders in Oakland to drop from 57 to 7 in 1997. Officials in New York found that only 29 of 950 FFLs were operating in compliance with local ordinances. In cooperation with BATF, all local license applications were forwarded to the New York Police Department, which assumed responsibility for screening

and inspections. The increased scrutiny reduced the number of license holders in New York from 950 to 259 (Veen et al., 1997).

These state-level and local initiatives have not been rigorously evaluated to determine whether they have affected criminal access to guns and rates of gun misuse.

Limiting Gun Sales

Federal law requires FFLs to report multiple firearms sales to BATF. A few states, including Virginia, Maryland, and California, have passed laws that limit the number of guns that an individual may legally purchase from FFLs within some specified time period. Underlying this intervention is the idea that some individuals make straw purchases in the primary market and then divert these guns to proscribed persons or others planning to do harm. Trace data analyses conducted by BATF suggest that handguns that were first sold as part of a multiple sale are more likely than others to move rapidly into criminal use (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, 2000c). If multiple sales were limited, then the volume of new guns available to criminals might decline. In the language of supply and demand, this is a supply-side intervention aimed at raising the price of new guns to criminals. In principle this sort of intervention holds promise. However, in order for this intervention to work—in the sense of reducing violence—not only must the intervention make it more difficult for criminals to get new guns but also the substitution possibilities must be limited; that is, comparably harmful guns cannot be available from comparably accessible sources.

In July 1993, Virginia implemented a law limiting handgun purchases by any individual to no more than one during a 30-day period. Prior to the passage of this law, Virginia had been one of the leading source states for guns recovered in northeast cities including New York, Boston, and Washington, DC (Weil and Knox, 1996). Using firearms trace data, Weil and Knox (1996) showed that during the first 18 months the law was in effect, Virginia’s role in supplying guns to New York and Massachusetts was greatly reduced. For traces initiated in the Northeast, 35 percent of the firearms acquired before one-gun-a-month implementation took effect and 16 percent purchased after implementation were traced to Virginia dealers (Weil and Knox, 1996). This study indicates a change in the origin of traced crime guns following the change in the law. In this sense, the law change had an effect. However, the law may have been undermined by a substitution from guns first purchased in Virginia to guns first purchased in other states.4 An important question not addressed by this study is whether the

law change affects the ultimate outcome of interest—the quantity of criminal harm committed with guns—or even the intermediate questions of the law’s effects on the number of guns purchased or owned.

Screening Gun Buyers

Enacted in 1994, the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act required FFLs to conduct a background check on all handgun buyers and mandated a one-week waiting period before transferring the gun to the purchaser. A total of 32 states were required to implement the provisions of the Brady act. The remaining states5 and the District of Columbia were exempted because they already required a background check of those buying handguns from FFLs. In 1998, the background check provisions of the Brady act were extended to include the sales of long guns and the waiting period requirement was removed when, as mandated by the initial act, it became possible for licensed gun sellers to perform instant record checks on prospective buyers. The policy intent was to make gun purchases more difficult for prohibited persons, such as convicted felons, drug addicts, persons with certain diagnosed mental conditions, and persons under the legal age limit (18 for long rifles and shotguns, 21 for handguns). In 1996, the prospective purchasers with prior domestic violence convictions were also prohibited from purchasing firearms from FFLs.

Theoretically, by raising the cost of acquisition, this procedure reduces the supply of guns to would-be assailants and to some persons who might commit suicide. Several BJS studies have demonstrated that Brady background checks have created obstacles for prohibited persons who attempt to purchase a gun through retail outlets (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999, 2002). The Bureau of Justice Statistics (2002) reported that, from the inception of the Brady act on March 1, 1994, through December 31, 2001, nearly 38 million applications for firearms transfers were subject to background checks and some 840,000 (2.2 percent) applications were rejected. In 2001, 66,000 firearms purchase applications were rejected out of about 2.8 million applications (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2002). Prospective purchasers were rejected because the applicant had a felony conviction or indictment (58 percent), domestic violence misdemeanor conviction or restraining order (14 percent), state law prohibition (7 percent), was a fugitive from justice (6 percent), or some other disqualification, such as having a drug addiction, documented mental illness, or a dishonorable discharge (16 percent) (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2002).

These figures suggest the possibility that the Brady act might be effective in screening prohibited purchasers from making gun purchases from FFLs. Based on descriptive studies revealing heightened risks of subsequent gun offending, some researchers suggest extending the provisions of the Brady act to a wider range of at-risk individuals, such as persons with prior felony arrests (Wright et al., 1999) and misdemeanor convictions (Wintemute et al., 1998). Wright et al. (1999) compared the gun arrest rates of two groups in California. The first consisted of persons who were denied purchases because they had been convicted of a felony in 1977. The second was purchasers who had a prior felony arrest in 1977 but no conviction. Even though the former group would reasonably be labeled as higher risk, they showed lower arrest rates over the three years following purchase or attempt to purchase. It is important to recognize that the group of convicted felons who attempt to purchase through legal channels may be systematically lower risk than the entire felony population, precisely because they did attempt to use the prohibited legitimate market; the finding is suggestive rather than conclusive

Wintemute et al. (1998) also recognize that extending the provisions of the Brady act would greatly complicate the screening process. Moreover, while this policy seems to prevent prohibited persons from making gun purchases in the primary market, the question remains what, if any, effect it has on purchases in the secondary market, on gun crimes, and on suicide.

Using a differences-in-differences research design and multivariate statistics to control for state and year effects, population age, race, poverty and income levels, urban residence, and alcohol consumption, Ludwig and Cook (2000) compared firearm homicide and suicide rates and the proportion of homicides and suicides resulting from firearms in the 32 states affected by Brady act requirements (the treatment group) compared with the 19 states and the District of Columbia (the control group) that had equivalent legislation already in place. Ludwig and Cook (2000) found no significant differences in homicide and suicide rates between the treatment and control groups, although they did find a reduction in gun suicides among persons age 55 and older in the treatment states. This reduction was greater in the treatment states that had instituted both waiting periods and background checks relative to treatment states that only changed background check requirements. The authors suggest that the effectiveness of the Brady act in reducing homicides and most suicides was undermined by prohibited purchasers shifting from the primary market to the largely unregulated secondary market.

While the Brady act had no direct effect on homicide rates, it is possible that it had an indirect effect, by reducing interstate gun trafficking and hence gun violence in the control states that already had similar laws. Cook and Braga (2001) document the fact that criminals in Chicago (a

high control jurisdiction) were being supplied to a large extent by illegal gun trafficking from south central states, in particular Mississippi, and that a modest increase in regulation—imposed by the Brady act—shut down that pipeline. However, this large change in trafficking channels did not have any apparent effect in gun availability for violent acts in Chicago, as the percentage of homicides with guns did not drop after 1994 (Cook and Braga, 2001). Moreover, the authors found that the percentage of crime handguns first purchased in Illinois increased after the implementation of the Brady act, suggesting substitution from out-of-state FFLs to instate FFLs once the advantage of purchasing guns outside Illinois had been removed.

Gun Buy-Backs

Gun buy-back programs involve a government or private group paying individuals to turn in guns they possess. The programs do not require the participants to identify themselves, in order to encourage participation by offenders or those with weapons used in crimes. The guns are then destroyed. The theoretical premise for gun buy-back programs is that the program will lead to fewer guns on the streets because fewer guns are available for either theft or trade, and that consequently violence will decline. It is the committee’s view that the theory underlying gun buy-back programs is badly flawed and the empirical evidence demonstrates the ineffectiveness of these programs.

The theory on which gun buy-back programs is based is flawed in three respects. First, the guns that are typically surrendered in gun buy-backs are those that are least likely to be used in criminal activities. Typically, the guns turned in tend to be of two types: (1) old, malfunctioning guns whose resale value is less than the reward offered in buy-back programs or (2) guns owned by individuals who derive little value from the possession of the guns (e.g., those who have inherited guns). The Police Executive Research Forum (1996) found this in their analysis of the differences between weapons handed in and those used in crimes. In contrast, those who are either using guns to carry out crimes or as protection in the course of engaging in other illegal activities, such as drug selling, have actively acquired their guns and are unlikely to want to participate in such programs.

Second, because replacement guns are relatively easily obtained, the actual decline in the number of guns on the street may be smaller than the number of guns that are turned in. Third, the likelihood that any particular gun will be used in a crime in a given year is low. In 1999, approximately 6,500 homicides were committed with handguns. There are approximately 70 million handguns in the United States. Thus, if a different handgun were used in each homicide, the likelihood that a particular handgun would be

used to kill an individual in a particular year is 1 in 10,000. The typical gun buy-back program yields less than 1,000 guns. Even ignoring the first two points made above (the guns turned in are unlikely to be used by criminals and may be replaced by purchases of new guns), one would expect a reduction of less than one-tenth of one homicide per year in response to such a gun buy-back program. The program might be cost-effective if those were the correct parameters, but the small scale makes it highly unlikely that its effects would be detected.

In light of the weakness in the theory underlying gun buy-backs, it is not surprising that research evaluations of U.S. efforts have consistently failed to document any link between such programs and reductions in gun violence (Callahan et al., 1994; Police Executive Research Forum, 1996; Rosenfeld, 1996).

Outside the United States there have been a small number of buy-backs of much larger quantities of weapons, in response to high-profile mass murders with firearms. Following a killing of 35 persons in Tasmania in 1996 by a lone gunman, the Australian government prohibited certain categories of long guns and provided funds to buy back all such weapons in private hands (Reuter and Mouzos, 2003). A total of 640,000 weapons were handed in to the government (at an average price of approximately $350), constituting about 20 percent of the estimated stock of weapons. The weapons subject to the buy-back, however, accounted for a modest share of all homicides or violent crimes more generally prior to the buy-back. Unsurprisingly, Reuter and Mouzos (2003) were unable to find evidence of a substantial decline in rates for these crimes. They noted that in the six years following the buy-back, there were no mass murders with firearms and fewer mass murders than in the previous period; these are both weak tests given the small numbers of such incidents annually.

Banning Assault Weapons

In 1994, Congress enacted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, which banned the importation and manufacture of certain military-style semiautomatic “assault” weapons and ammunition magazines capable of holding more than 10 rounds (National Institute of Justice, 1997). Assault weapons and large-capacity magazines manufactured before the effective date of the ban were grandfathered and thus legal to own and transfer. These guns are believed to be particularly dangerous because they facilitate the rapid firing of high numbers of shots. While assault weapons and large-capacity magazines are used only in a modest fraction of gun crimes, the premise of the ban was that a decrease in their use may reduce gunshot victimization, particularly victimizations involving multiple wounds or multiple victims (Roth and Koper, 1997).

A recent evaluation of the short-term effects of the 1994 federal assault weapons ban did not reveal any clear impacts on gun violence outcomes (Koper and Roth, 2001b). Using state-level Uniform Crime Reports data on gun homicides, the authors of this study suggest that the potential impact of the law on gun violence was limited by the continuing availability of assault weapons through the ban’s grandfathering provision and the relative rarity with which the banned guns were used in crime before the ban. Indeed, as the authors concede and other critics suggest (e.g., Kleck, 2001), given the nature of the intervention, the maximum potential effect of the ban on gun violence outcomes would be very small and, if there were any observable effects, very difficult to disentangle from chance yearly variation and other state and local gun violence initiatives that took place simultaneously. In a subsequent paper on the effects of the assault weapons ban on gun markets, Koper and Roth (2001a) found that, in the short term, the prices of assault weapons in both primary and legal secondary markets rose substantially at the time of the ban, and this may have reduced the availability of the assault weapons to criminals. However, this increase in price was short-lived as a surge in assault weapon production in the months prior to the ban and the availability of legal substitutes caused prices to fall back to nearly preban levels. The ban is also weakened by the ease with which legally available guns and magazines can be altered to evade the intent of the ban. The results of these two studies should be interpreted with caution, since any trends observed in the relatively short study time period (24-month follow-up period) are unlikely to predict long-term trends accurately.

District of Columbia Handgun Ban

Bans on the ownership, possession, or purchase of guns are the most direct means available to policy makers for reducing the prevalence of guns. The District of Columbia’s Firearms Control Regulations Act of 1975 is the most carefully analyzed example of a handgun ban. This law prohibited the purchase, sale, transfer, and possession of handguns by D.C. residents other than law enforcement officers or members of the military. Note, however, that individuals who had previously registered handguns prior to the passage of this law were allowed to keep them under this law. Long guns were not covered by the ban.6

One would expect the passage of the District’s handgun ban to have little impact on the existing stock of legally held handguns but to greatly reduce the flow of new handguns to law-abiding citizens. Over time, the number of legally held handguns will decline. It is less clear how the illegal

possession of guns will be affected. The flow of new guns to the illegal sector may be reduced to the extent that legal guns enter the illegal sector through resale or theft from the legal stock in the District. Theory alone cannot determine whether this handgun ban will reduce crime and violence overall. One would expect that the share of crimes in which guns are used should decline over time if the handgun ban is effective.

The empirical evidence as to the success of the Washington, DC, handgun ban is mixed. Loftin et al. (1991) used an interrupted-time-series methodology to analyze homicides and suicides in Washington, DC, and the surrounding areas of Maryland and Virginia before and after the introduction of the ban. They included the suburban areas around Washington, DC, as a control group, since the law does not directly affect these areas. Using a sample window of 1968-1987, they report a 25 percent reduction in gun-related homicides in the District of Columbia after the handgun ban and a 23 percent reduction in gun-related suicides. In contrast, the surrounding areas of Maryland and Virginia show no consistent patterns, suggesting a possible causal link between the handgun ban and the declines in gun-related homicide and suicide. In addition, Loftin et al. (1991) report that nongun-related homicides and suicides declined only slightly after the handgun ban, arguing that this is evidence against substitution away from guns toward other weapons.

Britt et al. (1996), however, demonstrate that the earlier conclusions of Loftin et al. (1991) are sensitive to a number of modeling choices. They demonstrate that the same handgun-related homicide declines observed in Washington, DC, also occurred in Baltimore, even though Baltimore did not experience any change in handgun laws.7 Thus, if Baltimore is used as a control group rather than the suburban areas surrounding DC, the conclusion that the handgun law lowered homicide and suicide rates does not hold. Britt et al. (1996) also found that extending the sample frame an additional two years (1968-1989) eliminated any measured impact of the handgun ban in the District of Columbia. Furthermore, Jones (1981) discusses a number of contemporaneous policy interventions that took place around the time of the Washington, DC, gun ban, which further call into question a causal interpretation of the results.

In summary, the District of Columbia handgun ban yields no conclusive evidence with respect to the impact of such bans on crime and violence. The nature of the intervention—limited to a single city, nonexperimental, and accompanied by other changes that could also affect handgun homicide—make it a weak experimental design. Given the sensitivity of the results to alternative specifications, it is difficult to draw any causal inferences.

SUMMARY

We have documented what is known about how people obtain firearms for criminal activities and identified the weaknesses of existing evaluations of interventions. There is not much empirical evidence that assesses whether attempts to reduce criminal access to firearms will reduce gun availability or gun crime. Most research has focused on determining whether prohibited persons illegally obtain firearms from legitimate commerce (legal primary and secondary markets) or whether crime guns are stolen or acquired through informal exchanges. Current research evidence suggests that illegal diversions from legitimate commerce are important sources of guns and therefore tightening regulations of such markets may be promising. There also may be promising avenues to control gun theft and informal transfers (through problem-oriented policing, requiring guns to be locked up, etc.). We do not yet know whether it is possible to actually shut down illegal pipelines of guns to criminals or what the costs of such a shutdown would be to legitimate buyers. Answering these questions is essential.

We also provide an analytic framework for assessing interventions. Since our ultimate interest is in the injuries caused using guns and not how guns are obtained, the key question involves substitution. In the absence of the pathways currently used for gun acquisition, could individuals have obtained alternative weapons with which to wreak equivalent harm?

Substitution has many dimensions; time, place, and quality are just some of them. For example, that crime guns tend to be newer than guns generally indicates that criminals prefer new guns, even though old guns are generally as easy to get and are cheaper. This may be strictly consumer preference, or it may be to avoid being implicated, through ballistics imaging, in other crimes in which the gun was used. Would offenders currently using newer guns use older guns—or any guns—if access to newer guns became more limited? If particular dealers account for a disproportionate share of crime weapons, then we are left with yet another version of the substitution question: Would the criminals have obtained other guns, with similar harmful effects, from other sources, including other FFLs? How long would this process of substituting from new to old or from one source to another take?

What data are needed to determine the extent of substitution among firearms? Much could be learned from individual-level data from a general population survey on the number of guns owned by length of time, along with detailed individual characteristics of the individual (age, demographic characteristics, psychiatric history, other high-risk behaviors), along with type of gun owned (if any) and the method of acquisition (retail purchase, legal purchase of used gun, illegal purchase of stolen gun, borrowed through informal network). In addition, one would want measures of the availabil-

ity of firearms of each type to potential buyers of each type in each locale. For adults without criminal records, for example, there are established, observable prices of new guns at retail outlets. Similarly, there are active markets in used guns, for which there are (at least in principle) prices. The prices are individual specific in the sense that, for example, juveniles and felons cannot purchase guns at Wal-Mart.8 In effect, they face an infinite price of guns through this channel.

Beyond this information one would also need a source of exogenous variation on the difficulty of obtaining guns through different channels. While guns available to legal buyers through retail outlets have literal prices, the measures of the difficulty of gun acquisition through some other channels are prices only in a metaphorical sense. When a city undertakes an intervention at a particular point in time, for example to make it more difficult for juveniles to get guns from interstate traffickers in new guns, then (provided that the policy has some effect), it is as if the price of guns to juveniles has risen. Provided that the timing of the intervention is independent of the time pattern of local gun use, we could treat it as an exogenous increase in the metaphorical price of a gun to juveniles; money prices may fall as other costs rise because this increase in nonmoney costs shifts the demand curve down. What happens to the tendencies for juveniles to obtain guns; do they substitute purchases of guns stolen from homes for the new guns they had previously purchased from traffickers? Is the substitution complete? That is, is the volume of juvenile gun use as high in the presence of the intervention as it was in the absence of the intervention?

The biggest potential problem with this framework, however, is the assumption of an exogenous intervention. No real intervention is likely to be exogenous; that is, unrelated to changes in gun crimes. It might be more realistic to think about exogeneity conditional on some specified set of covariates, but the prospects for finding consensus on the correct set of covariates to credibly maintain this independence assumption are unknown. Alternatively, researchers may be forced to rely on other methodological approaches and data.

The committee has not attempted to identify specific interventions, research strategies, or data that might be suited for studying market interventions, substitution, and firearms violence. The existing evidence is of limited value in assessing whether any specific market-focused firearm restrictions would curb harm. Thus, the committee recommends that work be started to think carefully about the prospects for achieving “conditional exogeneity,” the kinds of interventions and covariates that are likely to

satisfy this independence requirement, how one could gather the data, the potential for building in evaluation at the stage of policy change, and other possible research and data designs. Future work might begin by considering the utility of emerging data systems, described in this report, for studying the impact of different market interventions, This type of effort should be take place in collaboration with a group of survey statisticians, social scientists, and representatives from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the National Institute of Justice.