2

Plenary Session

Introduction of the Symposium and of the Director of the National Cancer Institute

Harvey Fineberg, M.D., Ph.D.,

President, Institute of Medicine

Good morning, everyone. It is a great pleasure for me to have this opportunity to welcome all of you to this symposium today. As you know, we are here to consider the ways in which the report Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection can be moved along to the next step: realization.

At the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Academies more generally, we are very accustomed to the task of producing a report. I have often said to our folks here that when the report is done, the project is really only half complete, because what matters is not what is written on a piece of paper; what matters is what happens in peoples’ lives as a consequence. A report is not done until it has been acted upon, and action is not complete until it has had an effect in the world.

So this gathering of all of you who are so engaged and committed to the task of cancer prevention and early detection is part of that task of completion: the task of moving forward together, beyond words on a page to actions by individuals, in clinical care, by health professionals, by institutions, by government. We will have the opportunity through the course of this day to engage in discussion of ways that we can move forward.

I am also very pleased that this program was sponsored jointly with the American Cancer Society (ACS) which over the years has done so much to enlighten the American public and to draw together resources and attention to the critical problem of cancer prevention. John Seffrin, I want to thank

you on behalf of all of us here for your support and sharing in this partnership.

There is hardly anyone who is better suited to start us off today than the Director of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach. Dr. von Eschenbach, prior to the time that he was scheduled to become the Director of the National Cancer Institute, was poised to take over at the American Cancer Society as president-elect, so he has been detoured from that duty but, I understand from Dr. Seffrin, not permanently excused. Dr. von Eschenbach is a man whose professional life long has been committed to the very objectives that we are talking about today, and that he has championed in his term as the Director, which he began in the year 2001. It is a great privilege for me to have this opportunity to welcome and to introduce my friend, our Director of the National Cancer Institute, Dr. Andrew von Eschenbach.

Cancer Prevention and Early Detection: Key Strategies for Challenge Goal 2015

Andrew von Eschenbach, M.D.,

Director, National Cancer Institute

It is a great honor for me this morning to come as the Director of the National Cancer Institute, and begin with very sincere congratulations to you, to the Institute of Medicine and the National Academies, for the work, effort, and the product you have created with regard to the report on prevention and early detection. I believe this report will serve us well, not only as a road map for the future, but also as a means of bringing us together to walk that journey collaboratively and cooperatively, to be certain that in fact, we achieve all of the outcomes that we know are within our grasp.

This morning, I would like to spend the next few minutes with you, talking about that journey into the future, specifically talking to you about a destination that I believe is within view. I will talk about it from the standpoint of a research agenda that can lead us to that end point. I know that John Seffrin and others can talk very eloquently about this from the perspective of a cancer control agenda, but of course, both of these agendas are woven together into a very synergistic and complementary pattern. I would like to begin with a vision for this future destination. I think it was summed up very well at a recent important ceremony in the White House celebrating cancer survivorship, and the fact that we have moved from three million cancer survivors in this country around the time that the National Cancer Act was signed in 1971 to now over 9.6 million cancer survivors alive within the United States today.

President Bush noted at the ceremony that for the first time in human history, we can say with certainty that the war on cancer is winnable, and that this nation will not quit until this victory is complete. Obviously, we are very pleased with the commitment to continue on in this effort. But I think what is really interesting and at the heart of the matter is the realization that perhaps today for the first time, we have the ability to recognize with certainty that the ability to conquer cancer is within our grasp. The reason why that is true, in my opinion, or one of the reasons why it is true, is because of the investment that we have made in basic and clinical biomedical research, and because of the kinds of things that have been promoted by organizations like the National Academies. The result is that our 21st century quest to truly understand the fundamental nature of matter and the tremendous revolution that has occurred in biomedical research have now brought us to the point that Andy Grove describes as a very magical moment in time called the “Strategic Inflection”: that time in which, by unraveling the secrets of the cell nucleus, we are creating entirely new paradigms in our ability to deal with diseases like cancer.

This strategic inflection in which we are immersed, this ability to now approaching diseases in fundamentally different ways, is in fact being led by the tremendous investment in cancer research. In that regard, the idea of the strategic inflection simply is the realization that with regard to diseases like cancer, for the first time we are really understanding cancer as a disease process, and understanding it at the very fundamental genetic, molecular, and cellular mechanisms. This strategic inflection, this new paradigm, is really creating for us extraordinary opportunities that enable us to begin to approach the burden of disease in fundamentally different ways. Instead of simply seek and destroy, find and kill, we now are opening up an entirely new portfolio in our ability to control cancer, to modulate it, as well as to eliminate it. That has created an opportunity for us. But it is more than an opportunity; it is in fact a responsibility and perhaps even a moral imperative. With the tremendous progress that has been made, with the enormous opportunity within our grasp, we now need to look into the face of cancer and recognize that it doesn’t have to be the way that it has been. We should look to a future in which we can fundamentally change cancer.

In this regard, the National Cancer Institute has set a very bold, a very ambitious, and to some a very shocking goal. The goal is that we will eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer, and we will bring that about by 2015. We did not say we will eliminate cancer; we said we would eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer or eliminate the burden of disease. We will bring that about because we are in the midst of the strategic inflection in which we have assembled a significant amount of financial and intellectual capital. It may not be as much as we need for the future, but it is more than has ever been assembled before. In addition to the financial resources and

intellectual capital, another important development is that this entire effort is immersed in what has been essentially an explosion in enabling technologies. This has made the rate and the pace of progress exponential and exhilarating.

So, in terms of the strategy to eliminate the burden, the outcome, and the suffering and death that results from cancer, we can begin to think about a process of pre-emption. Pre-emption is a strategy that enables us to inhibit or pre-empt the initiation and the progression of cancer on its way to a lethal phenotype. We recognize cancer as a process. Doug Hanahan and Bob Weinberg have talked about the six essential steps associated with the process of cancer. If we now begin to think about the product of our investment in research as giving us an understanding of cancer as a disease process, we begin to see that there are multiple steps within that process that make cancer vulnerable. We can think about it as a process in which even before malignant transformation, there is a stage of the process in which we are susceptible to disease, susceptible because of exposure to things like tobacco, or susceptible just because of aging. There is a period of time in that process of susceptibility, and then a moment where there is actually a malignant transformation, and once that occurs, evolution of that transformation to the point where we actually encounter clinical disease. Then there is a continuation through a very complex series of events which ultimately give rise to the lethal phenotype of cancer, namely, the metastatic phenotype. Only then, at the end of that process, over a period, of time does cancer succeed in taking a person’s life.

As we begin to think of this process and the burden over time, we can begin to think now of our ability to capitalize on our understanding of the multiple steps in this disease process. We can begin to think of a series of interventions that we can then apply, that are truly transformational, based on our new knowledge, to affect this disease process, and change its behavior. There are many steps, and these are at least a few of the possible steps that are associated with the evolution of the lethal phenotype of disease. In fact, patients do not generally die as the result of a primary tumor. Patients die due to the fact that we ultimately have a process of metastasis and evolution to a lethal phenotype. All of these steps and processes have been the subject of intense scientific scrutiny in cancer research, but there are also now incredibly rich opportunities for us with regard to interventions.

So as we think of this disease process, and as you go about your deliberations, we can begin to consider ways to interfere even in the premalignant phase of this process by preventing the actual transformation. Once that transformation occurs, multiple interventions are possible to detect it early at a time when we can apply effective interventions and strategies that we already have available, along with other strategies to modulate and

alter that evolution of pre-malignant disease into the process of clinical disease.

Finally, we have a whole portfolio of opportunities to interfere with the evolution of clinical disease to a malignant lethal phenotype of metastasis. So we begin to think about cancer as being preventable, able to be eliminated or modulated, so that patients do not die as a result of cancer. That is at the heart of the pre-emption strategy: a strategy along the same lines we use to modulate diseases like diabetes. The ultimate outcome is to enable people to live with and not die from cancer, to eliminate the suffering and death that occurs as a result of the disease. We will incorporate a comprehensive strategy of prevention, detection, elimination, and treatment of advanced disease and modulation of the disease process. There will not be a single magic bullet. There is no single intervention that will accomplish this. But there can be a significant strategy of integration of these interventions to enable us to bring about the outcome of modulation and elimination of suffering and death.

We have chosen to approach this at the National Cancer Institute in the context of a portfolio of investment in three areas: discovery; development; and delivery. This enables us to continue to drive our understanding of these fundamental mechanisms by our investment in fundamental research, but to rapidly translate that knowledge and understanding of cancer as a disease process into the development of interventions for detection, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of the disease, and then to be certain that we are using our infrastructure to deliver those interventions to all who are in need. We can think about detection, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention as a systems biology approach or an integrated approach, in which we are looking at all the components, those components that are operative in the cancer cell or the tumor, those components that affect the person or the host, and particularly the tumor-host interactions. We can also look at the process of cancer as it relates to the environment or populations and gene-environmental interactions, and it is in all these interactions that we will ultimately achieve our desired outcome.

We are launching a number of new initiatives that we will guide and modulate over time to continue to drive towards successfully eliminating the suffering and death due to cancer. This morning I want to spend time touching upon some of the very important issues with regard to prevention, early detection, and elimination. We have a significant investment in our portfolio of cancer prevention, and that investment continues to grow. It is a very balanced portfolio, looking at all the varieties and various elements that will enable us to contribute to the prevention and early detection strategies. As you know, very recently we launched a significant and major investment in early detection of lung cancer with regard to the role of spiral C-T scanning as compared to chest X ray. I point this out for two reasons, one, because of

how just one single intervention can have a significant impact on the suffering and death due to disease. With the ability to detect lung cancer earlier than we are currently able to, we will have the opportunity to change a disease that carries with it an 85 percent mortality rate to one that could carry an 87 percent survival rate, just with currently available interventions and strategies. The other reason for pointing this out is the need for collaboration and cooperation. One of the very major successes in this study is that within its first nine months of being launched, it was ahead of its accrual goals. One of the important aspects of the launch of this study was a collaboration with the American Cancer Society to work in the community around the 30 centers that are carrying out this study to promote education, awareness, and recruitment to this study. So, again, it is a collaborative effort to achieve success.

We have investments in gene-environmental studies to look at mechanisms of susceptibility, because it is critical for us to understand those interactions that occur, that determine our susceptibility to cancer and the trans-formations that occur, and to segment populations into populations at risk, so that we can strategically apply the most effective and the most appropriate strategies for prevention. We need to continue to pay attention to the important elements related to the person with cancer. You are aware of the tremendous investment that we have made in tobacco cessation. I point out again the important success of the strategy, namely the trans-disciplinary tobacco research centers. These TTRCs, which are truly transdisciplinary in nature, have had a major impact on our understanding of the full complexity of tobacco addiction, on the impact that tobacco has on persons.

The other important aspect of that effort is to realize our opportunity to apply the lessons learned from tobacco research to other major challenges, especially the ones we have identified with regard to our need to address the problem of diet. You are going to hear later about the important collaborative and cooperative efforts that we have on the subject of energy balance where we are looking at the interaction of diet and physical activity. You will also hear about the important trans-HHS initiatives that are underway in this regard.

Prevention and early detection through screening are exceedingly important. We have a significant number of efforts underway to understand our ability to modulate and prevent disease, not only from the standpoint of behavioral modification but also of chemopreventive strategies. You are aware of the very recent publication around the role of finasteride. Peter Greenwald has been at the forefront of that and will speak to that in more detail. But we have established at least proof of principle that chemoprevention in an area such as prostate cancer is achievable, with a 25 percent reduction in incidence. Many questions need to be answered about the biology of prostate cancer and the impact of a chemoprevention strategy like finasteride, but

proof of principle is established that we can reduce the incidence of that malignant process.

We also have a variety of other opportunities with the COX-2 inhibitors, and the like, with regard to chemoprevention strategies in diseases where prevention alone could significantly affect suffering and death due to those cancers. And we have opportunities with regard to risk identification and the important role that the human papilloma virus plays, especially in cancer of the cervix. We have an opportunity through the development of cancer vaccines and the cervical cancer vaccine trials that are underway to be able to eliminate disease by a preventative interventional strategy.

As I mentioned earlier, we have tremendous opportunities with regard to early detection. I have alluded to the impact the national lung screening trial could have through just one intervention such as a radiological technique. But the opportunity that is opening in biomarkers, particularly with protein profiles, is truly mind-boggling. Our opportunities in genomics and proteomics, in terms of our ability to detect cancer early in its course and predict its biologic behavior, are rapidly unfolding advantages from our proteomics initiative. We have, as you are aware, a number of proteomic early detection strategies underway based on some of the experience of looking at protein profiles. In regard to ovarian cancer, these studies are evolving and continuing to track with 100 percent specificity and complete sensitivity the use of proteomic profiles for the detection of early ovarian cancer. These strategies are being applied to other diseases as well.

I have mentioned the importance of collaboration. Collaboration is at the core of the success that will be necessary to achieve the 2015 goal to eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer. One important collaboration I bring to your attention is the very recent interagency agreement and formation of a joint task force that the NCI has established with the Food and Drug Administration. Our goal is to optimize and accelerate our ability to move these interventions rapidly through discovery, development, and delivery and through the approval process, so that they can be applied effectively to patient populations. This is important to the work that you are going to be discussing. As we look at strategies for chemoprevention, as we look at strategies for the development of devices for early detection, and as we look at the opportunity to apply those, one key element in our ability to save lives and eliminate suffering is to be able to move those very quickly to the point where they can be applied to patients. That is at the core of that important collaboration. But there are a host of other partnerships that are critically important as well.

Many of you in the room are a part of those interactions and a part of those efforts. To eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer, and to accomplish that by 2015, is a bold pronouncement. But it is achievable based on the accomplishments that people like you are making possible. It is

achievable based on the incredible progress that we have made up to now, and based on the unbelievable progress that is within our grasp as we continue on this exponential upward trajectory, in this strategic inflection that will truly change the face of cancer and other diseases as well. It is a privilege for me to be able to share with you a glimpse, and it is only a glimpse, of what we are committed to doing to bring this about, and most important, to reaffirm to you the NCI’s commitment to work collaboratively and cooperatively together with you. Working together, we can bring about the objectives and realize the opportunities to accomplish this goal.

View from the ACS: Fulfillment of the Potential of Cancer Prevention

John Seffrin, Ph.D., CEO, American Cancer Society

It is a privilege for me to be here and to represent the American Cancer Society, the world’s largest voluntary health organization and the largest not-for-profit in America today that receives over 90 percent of its total support from private contributions. I am grateful for this opportunity to share with you our thoughts on the critically important topic that brought us here today, namely, the prestigious Institute of Medicine’s recently released report, Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection.

This report, which provides comprehensive evidence-based recommendations for clear opportunities to dramatically reduce our nation’s cancer burden, is a clarion call to action for all of us and for this great nation to put in place key interventions which will make a difference in lives saved and suffering averted from cancer. The twelve recommendations highlighted in this report underscore what is possible in advancing the fight against this disease. Now it is up to us and others in this room and beyond to put teeth into these recommendations through further research and most importantly, implementation. Contemplate the following statement: If implemented and properly resourced, we simply don’t know anything else that can have a greater impact on this nation’s public health in as favorable a way. Think about that.

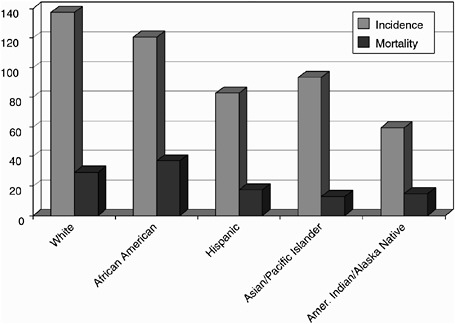

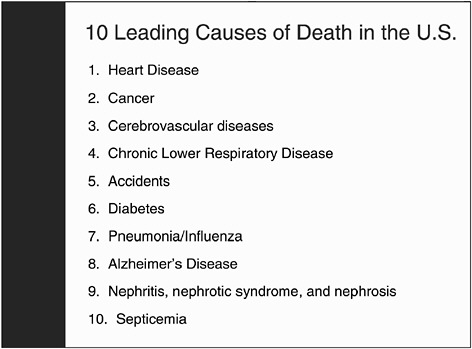

Let me begin my remarks today by stressing the unmistakable and remarkable opportunity we have to prevent premature death and unnecessary suffering in this nation—not only from cancer, but other diseases, too. Our nation’s leading causes of death are listed in order in Figure 1. I want to pause and have you consider them with me. I suppose there must be 10,000 ways that you can check out of this world. When I was in graduate school, we looked at birth certificates from the turn of the century, when a common

Figure 1. The ten leading causes of death in the United States. SOURCE: Mortality Public Use Data Tape 2000, National Cancer Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002.

cause of death was being kicked by a horse. We live in a nation where we have roughly two million deaths per year. Would you believe me if I said that over 90 percent of those deaths were from one of this list often? These ten things, of the 10,000 ways you can check out of this world, really represent the ways in which people in our society die, and most often, they are dying prematurely. The most important thing about this list is that these diseases and health problems are largely preventable. They are certainly far more preventable than they are curable. So, indeed, for today and for the foreseeable future, prevention is the cure.

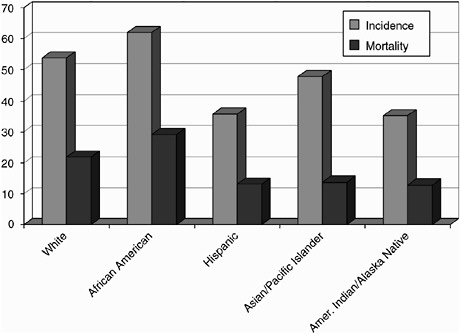

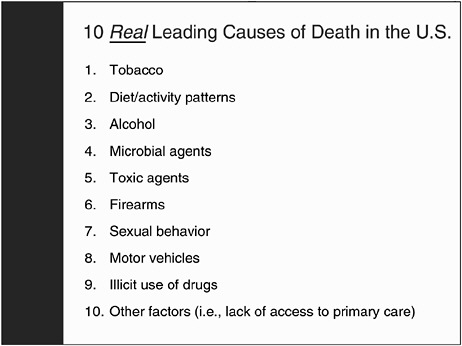

Figure 2 underscores the true root causes of death, and even more dramatically conveys the need for more aggressive national strategies to promote healthy lifestyles. While cancer is certainly a leading cause of death, number two overall, and the leading cause of death during the prime of life, it need not be so. If opportunities to prevent and control cancer were fully seized and realized, millions of lives could be saved. Cancer, the disease Americans most care about and most fear, over time, as we have already heard, could be eliminated as a major public health problem. What is more,

Figure 2. Medical perspective of the ten leading causes of death in the United States. SOURCE: McGinnis and Foege, 1993.

prevention strategies would also significantly reduce risks of dying prematurely from other diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes, along with cancer. So on that list of ten, add those five up, and we are talking about 80 percent of all of the deaths last year.

We are beginning to understand that if we focus on the right things, we could have an extraordinary, historically unprecedented impact on this nation’s public health. Where is the evidence? Today, for the first time in our nation’s history, we are witnessing sustained declines in overall adjusted cancer incidence and mortality rates in the United States. The trend is down, respectively, 7.5 and 7.2 percent over the last 10 or so years. This is due in part, of course, to progress in research and improvements in cancer treatment, but mostly due to more effective primary and secondary prevention efforts. That is impressive, although you might say it is not a free fall. But from roughly 1991 to 2000, that represents in the aggregate 200,000 deaths that didn’t occur if the cancer mortality rates had remained the same. Remember, through most of the 20th century, the rates went up every year. But

even if they just stayed the same as they were in 1990, we are talking about saving 200,000 lives. Many of those whose lives were saved are in the prime of life—42,000 in the year 2000 alone.

With the exception of a spike around 1993 due to the widespread adoption of the PSA test, incidence rate downturns are real, though one might say, relatively modest, and they underscore two important points. First, cancer can in fact be controlled in this century if we do the right things. We have turned the corner on this disease, and while there is a great deal yet to be done, we are no longer simply trying to stem the ever-increasing tide of higher cancer incidence and mortality rates. Second, we have discovered that prevention works. That has always been true in theory, but now we have evidence. Indeed, we now know that some two-thirds or more of all cancers could be prevented if we intervened in the right ways more aggressively and with sufficient resources. The current trends prove the concept and bear witness to the progress that we have already made.

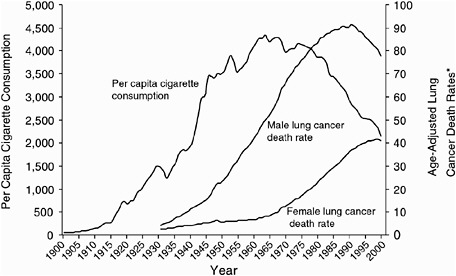

Here are just a few examples of the successes we have had in changing lifestyle behaviors to improve health and reduce the impact of cancer. Figure 3 shows the comparison between per capita cigarette consumption in the

Figure 3. Trends in tobacco use in the United States during the 1990s. SOURCE: Death rates: US Mortality Public Use Tapes, 1960–1999, US Mortality Volumes, 1930–1959, National Center for health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001. Cigarette consumption: US Department of Agriculture, 1900–1999.

U.S. and lung cancer mortality. Of course, we have known about the relationship between cigarettes and lung cancer. We have a literature of 50,000 studies about the causal relationship. But these data point out that you can change that, because if you can reduce the consumption, you can also reduce the diseases that it causes. Cigarette smoking prevalence rates in the United States for men and women show steady declines going back to 1964 when the first Surgeon General’s report was released. In spite of the powerful addicting effects of nicotine, people can quit. We now have over 50 million former smokers in America. So, the opportunity to have an impact is incredible. I’ll come back to that point later.

The prevalence of women reporting a recent mammogram has increased almost 40 percent, from 45 percent in 1990 to 63 percent in the year 2000. As you know, we have seen a decade of decline in breast cancer mortality in women in the United States. The prevalence of Pap tests within the past three years has remained high in women for a sustained period of time. Why go all the way back to the Pap test? Isn’t that history? Use of the test has actually increased in the late 1990s. As a result, cervical cancer mortality, which was a leading cause of cancer death of women in America (and is still the leading cause of cancer death in women in most other parts of the world), is now controlled for most women in this country, and could be eradicated if we could solve the access problem. This is a powerful, powerful example of what could be. As these data make clear, continued progress in prevention interventions is key, absolutely key, to the future public health of this nation. Our progress in reduced tobacco prevalence and better screening rates is linked to the reduction we see in mortality rates.

While we are gaining ground on a number of fronts, there are still many areas where we must redouble our efforts. One of those areas has to do with promoting healthier lifestyle behaviors which is critical to achieving what we now know is possible in cancer prevention and early detection. As is highlighted in the Institute of Medicine’s report: “Many of the behaviors that place individuals at risk for cancer are well recognized, and calls for behavioral change are not new. What is new is the growing body of evidence confirming the effectiveness of interventions to help people improve their health-related behaviors.” It seems to me that changes the whole dynamic. It actually elevates it to a moral imperative for a great nation such as ours if it really wants to walk the walk and not just talk the talk of saying we want to do what we can to improve the nation’s health.

In spite of all this, the epidemic of obesity may well prove to be every bit or even more challenging as other major public health threats like tobacco, and this is deeply troubling.

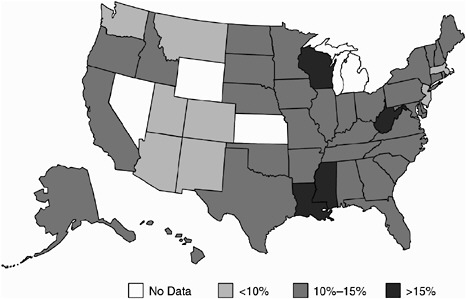

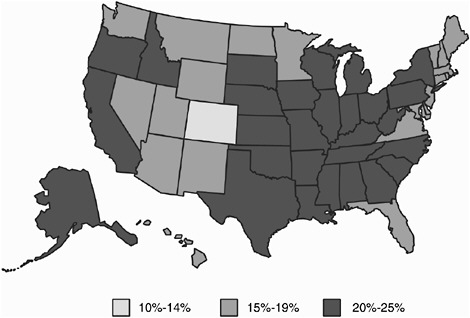

Today, in an overwhelming majority of U.S. states, more than 25 percent of all adults are obese, and the numbers are getting worse, not better. Of course, the obesity epidemic in this country is a major risk factor for numerous chronic conditions, and it threatens to undermine the progress we have made in other areas. Comparing Figures 4 and 5 illustrates how rapidly, from 1985 to 2001, obesity trends have increased and overwhelmed much of the country. What is troubling about this is that the data from the CDC indicates that the rates of increasing obesity are twice as high among our kids as they are for adults.

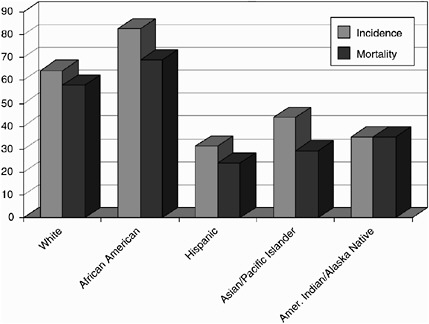

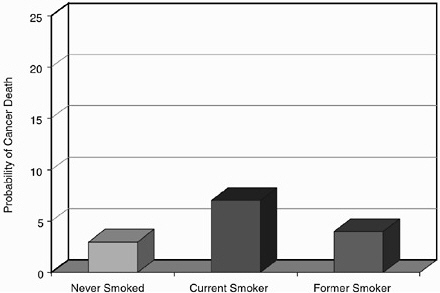

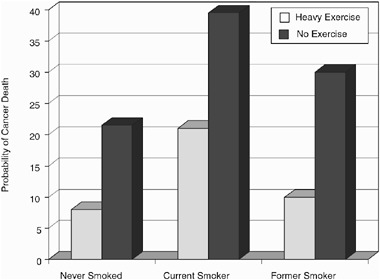

There are many factors that contribute to the soaring obesity trends in this country. Among them is our increasingly sedentary lifestyle. Let me share some data with you from the American Cancer Society’s Cancer Prevention Study II (CPS II), which demonstrates the startling impact of tobacco use combined with lack of exercise. CPS II, by the way, is the largest prospective epidemiologic trial ever undertaken in the history of public health. We have been following people since 1982, and will continue to do so throughout the course of their lives. Figure 6 shows the absolute probability in our study of premature death from cancer for women in mid-life based on smoking status. As you can see, which is no surprise, I’m sure, the woman who smokes is more than twice as likely to die of cancer in mid-life as her non-smoking counterpart. But if she quits, her chances of dying

Figure 6. Probability of death due to cancer among women ages 35 to 69 compared by smoking status.

decrease gradually and eventually return to near normal rates. One of the findings from this study that was most gratifying, particularly when we tracked women, is what happens if we can get to her before her 50th birth-day. We found we can save her life. So, here is a clear opportunity for prevention when time is on our side. It doesn’t have to happen by tomorrow. Because many people start smoking early in life, we may have years or decades to get to them, but we must get to them. Clearly the payoff is incredible.

The findings are much the same for men. Men who smoke are almost three times as likely to die from cancer in mid-life. But if they change their habits, they can reduce their risk, as has been well recorded and was the major theme of one of our Surgeon General’s reports.

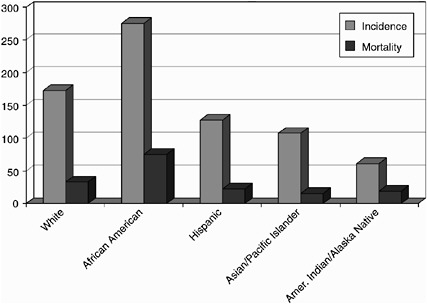

When we look at tobacco use combined with exercise patterns, just two risk factors, the impact is predictable, and it is still shocking. Women who exercise regularly and don’t smoke are less than a third as likely to die in mid-life than women who smoke and lead a sedentary life. The findings are even more dramatic for men. Men who smoke and do not exercise are almost five times as likely to die as those who exercise regularly and do not smoke. Now, there are data, and there are significant data, and then there are dramatically significant data. The key point is, to add to those factors body-mass index and diet, and you get dangerously close to flipping a coin as to

Figure 7. Probability of death among men between the ages of 35 and 69 compared by smoking and exercise status.

whether you die in mid-life or not. You may die at a time when you are most needed by your community and family. You may die in the prime of life.

The American Cancer Society, collaborating with others, continues to work to identify ways in which we can further prevent and control cancer. Here are just a couple of examples. The ACS supports evidence-based approaches to determining periodicity of age and gender-specific screening schedules for the early detection and prevention of cancer. Our guidelines have been developed in concert with—and publicly acknowledged by—multidisciplinary experts from the scientific and cancer communities. Furthermore, our guidelines for several major disease sites are complementary to those recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force, with both organizations striving to insure that the public is fully informed regarding life-saving cancer screening practices.

I was in town over the weekend for the meeting of the National Dialogue on Cancer, which the American Cancer Society is proud to be a part of with 150 other collaborating partners. The Dialogue’s CEO roundtable has developed something called “The Gold Standard,” which is evidence-based, state-of-the-art cancer screening and prevention guidelines in employee benefits. I am happy to say today that in 2004 some 37 CEOs from a number of major companies have agreed to include comprehensive cancer screening in their benefit plans. This initiative will improve cancer coverage for eight million employees, and when you include their children and family members, it ultimately reaches some 25 million Americans who will be covered by these state-of-the-art prevention guidelines. This will also include access to clinical trials. This is a tremendous opportunity. We also support the creation of reminder systems and other aids to assist the health care community in managing preventive care. Additionally, we believe it is important to place greater emphasis on prevention and early detection clinical trials, such as the National Lung Screening Trial that Dr. von Eschenbach has already mentioned. The American Cancer Society is very proud to be a collaborating partner in that project.

We believe that consistent messaging to the public across the voluntary health sector is also important. I am a little chagrined to share with you that it is only now for the first time in history that we are cooperating at the highest levels with the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association, through their CEOs and chief medical officers, to bring forth in 2004 a combined message about what the public needs to do to protect and promote better health. There will be clear messages about avoiding tobacco, preventing obesity, and the importance of medical checkups. Let me conclude by saying the Institute of Medicine’s report—and Harvey is absolutely right—is a first step, and a darned important first step, because it is based on the evidence. The National Cancer Policy Board and the Institute of Medi-

cine have done this nation a great service, because here it is: no brag, just fact, here is what can be done. It is a compelling piece.

Nonetheless, its implementation is obviously the key to seeing the end results, which are the improvement in the public’s health, and the improvement in the quality of individual and family lives. Indeed, if implemented, the results would be dramatic. It would make us the healthiest country in the world, which we are not now, even though we spend much, much more than any other nation on health care.

Cancer is potentially the most preventable and most curable of the major life threatening diseases facing Americans today. I believe that to turn that potential into reality requires a re-declared war on cancer and a battle plan based on prevention and building the nation’s public health infrastructure. I pray that God will speed the day.

How Many Lives Can Be Saved?

Tim Byers, M.D., M.P.H.,

Professor of Preventive Medicine and Associate Director,

University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center

I have a problem. I am an epidemiologist, and I have a problem remembering numbers. People ask me, what is the breast cancer incidence rate? I don’t know; I have to go look in a book. How many people are dying this year of heart disease? I don’t know, I can’t remember. I always have to go look in a book. How many people are dying this year of cancer? I’m a cancer epidemiologist, I can’t remember. I have to go look it up.

I have decided to speak to numbers in a little different way, by explaining to you how, in the preparation of this talk, I have come to try to think of numbers starting with the number one. There are a half million or so, 557,000 to be more precise, deaths from cancer in the U.S. this year. If you do the math, that comes down to one every minute. In the course of the ten-minute talk that I am giving, that is ten deaths. How many of those are preventable? Perhaps with a magic strategy, if not a magic bullet, all of them. Perhaps we could turn most of them into chronic disease; hopefully, we will achieve that in the next decade. There is another way to think about it, however. If a third of all cancer is due to tobacco, and of the remainder, another 20 or 25 percent is due to the combined effects of physical inactivity, poor nutrition, not eating enough fruits and vegetables, and the like, one can begin to calculate that of this half million deaths a year, perhaps two thirds are preventable by dealing with tobacco, nutrition, and a few other interventions like early detection.

Why then in Fulfilling the Potential of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection does the report begin with the lesser estimate that we came up

with four years ago in our 1999 ACS article (Byers et al., 1999)? Why does it begin with a more conservative number of 60,000 preventable deaths per year if we would close the gap between what we now know and what we now do? The entire report is a report on that gap, and the more conservative estimate is cited because it is based on the premise that we can’t do everything. We can’t make tobacco go away. We can’t reverse the epidemic of obesity or start screening everybody tomorrow. It is based on the premise that with additional efforts doing things that we know work—proven behavioral programs and other policies—with achievable, reasonable efforts, we could foresee improvements of about that order of magnitude, that is, about a ten percent further reduction. Now, that is not a ceiling, 60,000 deaths prevented, which in terms of minutes, by the way, in my ten-minute talk is one person. The reduction of 60,000 deaths that results in that one life saved just during these ten minutes is not a ceiling; it is a floor. I am assuming of course that we are going to re-double some efforts, that we are going to do some new things in tobacco, to bring the country to where Massachusetts and California are, and away from where we are in the South and in Kentucky and in places that aren’t making as much progress. So that is what that number means.

I took a walk last night after I got here. I was walking by the White House, and I remembered when I was first in Washington in 1971, which is when the National Cancer Act was being signed, and when the tobacco epidemic began to turn down. Those weren’t very prominent in my mind in 1971, because I was a student participating in one of the big marching protests against the Vietnam War. At that time, I was walking by the same spot I was walking by last night, the gates in front of the White House, and I was carrying a sign on my chest with the name of a boy from Kentucky who had died in Vietnam. I forget what his name was. I was carrying the candle and yelling out the name as I walked by the White House.

As I was remembering that last night, I looked down, and on that spot there was a rosebud, a beautiful little rosebud. So, I picked it up and I walked with it for awhile, and then was moved to go over to the Vietnam Memorial, and looked up randomly in the book there. The first Kentucky name I saw happened to have three names, the first, middle and last, and of the three names, one of them was mine and one of them was that of one of my children. I went to that spot, and on row 66, panel 9E, I found the name and laid the rose.

Then it occurred to me, there are 58,200 names on the Vietnam Memorial. That is a little less than 60,000. So, what do they mean—these numbers? The best definition of epidemiology is, it is the suffering of people with all the tears wiped away. What does 60,000 mean? If this is a conservative estimate of the number of lives we can save in this country every year by just doing some modest tweaking of the things that are already successfully

working—if that equates to one death as I am talking—what does that mean to us, and to what extent are we going to be moved ethically and morally or politically to take those kinds of actions? That is in fact what we are talking about today in our breakout sessions, what all the speakers are speaking to, what are the next steps, and what are the specific things that we can do.

I got a letter last week from a woman in Colorado that reminded me about the value of single lives. We are doing a mass mailing campaign in Colorado to Medicare beneficiaries to ask them to ask their physicians to give colon cancer screening, which is a Medicare benefit. We have tested this out, and we know we can get a five to ten percent bump in the screening rate. We are doing mass mailings to the entire state. After we did 35,000 mailings, I got a bunch of letters. One that I got last week was from a woman who said that the letter had come too late, that her husband had died of colon cancer after being seen for years by his physician for management of hypertension; in fact he had even had vascular surgery. Unfortunately, during all this time no one had told him to get screened. It is not a surprising story; it is happening all the time. We can reduce colon cancer death rates substantially in this country if we simply apply what we know. But most poignant to me was her comment at the close of her letter—we went to the moon in 1969, and you are telling me that we still have to be sending letters to people to do this now?

Applying the technology, applying what we know works, I think, is not so much an ethical imperative, actually, but a choice, an enormous opportunity to do enormous good. So in this meeting today, as we discuss how to close this gap between what we know and what we do, let’s remember that 60,000 is pretty conservative. We can do a lot better. If we can eventually eliminate tobacco and turn around the obesity epidemic, we can do a lot better than that. But even one person in ten minutes is not insignificant. As we sleep through the night, through tomorrow, through next week, through next month, those numbers add up to a lot of lives.

Harnessing the Power of Cancer Prevention and Early Detection

Susan J.Curry, Ph.D.,

Professor, Health Policy and Administration,

Director, Health Research and Policy Centers,

University of Illinois at Chicago

It is really a pleasure and a privilege to share ideas with you today about how to harness the power of cancer prevention and early detection. It is always gratifying to come to a symposium like this and see the level of inter-

est that has been generated in this important goal. I am going to start with the premises underlying my remarks. The first one is that we are not talking about radical changes. Modest shifts in the proportions of the populations at risk can make a big difference. Not everyone has to quit smoking, nor does everyone have to become a fitness buff. Moderate and achievable changes at the population level can make a significant difference. By way of illustration, if, on average, every American lost 2.2 pounds, that is, one kilogram, in the next year, we would see a 25 percent reduction in the prevalence of obesity.

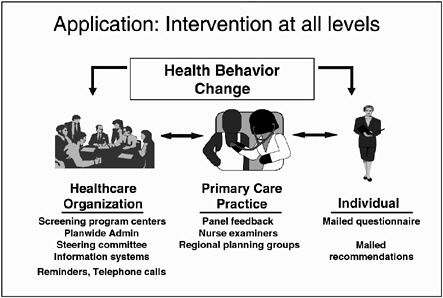

Second, although ultimately it comes down to individual behavior, it is important to focus our efforts on multiple levels. We don’t behave in a vacuum; we are influenced by the organizations that we interact with, our culture, environment, policy initiatives, and the like. Thirdly, different models or interventions are not necessary for different behaviors. There are more similarities than differences in what works. So if something works for one behavior, it can work for others. The fourth premise is that while we focus on preventing morbidity and mortality from cancer, achievements there will also reduce the morbidity and mortality from heart disease and diabetes and other major causes of disability and death. This synergistic effect is important as exemplified by the sobering statistic that each hour as many as 85 Americans will die prematurely from diseases other than cancer that are caused by tobacco use, inactivity, poor nutrition, and obesity.

The good news is that steps can be taken to reach our goals. Because I have a brief time in which to examine some of those steps, I will be selective. My comments will reflect my personal biases about where we can make a difference. I will touch on ways to harness the power of cancer prevention and early detection at the individual, organizational, and policy levels. At the individual level, we should increase access to, and demand for, state-of-the-art programs that facilitate healthful behavior changes. There is strong evidence that effective behavior change programs can be delivered by telephone, for example, particularly for tobacco cessation. There are successful models among state and national “health lines,” including state and national quit lines for tobacco use cessation. Evidence of their success has been published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Zhu et al., 2002). The Cancer Information Service has been leveraged to include participation in cancer screening and for the adoption of healthy eating behaviors. There is no reason why the infrastructure that is in place for these programs at the state and national levels could not be expanded. The availability of these resources should be accompanied by active mass media campaigns. Such campaigns create demand; they enhance motivation, and they can reinforce the changes that individuals make. As an example of how much demand a media campaign can create, recently New York City launched an initiative to provide free nicotine replacement therapy for smokers. The availability of this initia-

tive was widely advertised through the mass media. Over 280,000 calls were received, although the city had the resources to provide only 35,000 courses of treatment.

In an April speech at the National Press Club, entitled “A Little Prevention Won’t Kill You,” our Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Tommy Thompson, said: “The alarming growth rates of preventable disease also point to how out of whack our health care system is in America. We wait until people get sick before providing care. We invest mostly in developing technology or medicines to keep the sick living longer rather than preventing them from getting sick in the first place. This doesn’t make sense. We need to strike a better balance between preventive care and treatment.” I believe that we will achieve this balance if we can make prevention a standard of care in health care delivery. How can we do this? First, changing the culture of care begins with the training and licensing of health care providers. If it is a standard of care during training, it will be a standard of care during practice.

Second, health care systems do respond to outside influences. Employers and major purchasers of health care can hold systems accountable for the delivery of preventive care. The New England Journal of Medicine (Bodenheimer and Sullivan, 1998a and b) has documented successful examples of this kind of response. Accreditation organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) or the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations can include prevention-related performance indicators. For example, NCQA does this for tobacco cessation assistance, mammography, and cervical cancer screening. These efforts can be built upon.

Front-line health care providers need resources and accountabilities for prevention as a standard of care. We are trying to bridge the gap between what we know and what we do, and we know a lot. Unfortunately, that means there is a lot for health care providers to remember. Clinical information systems that allow doctors to track their patients’ progress, identify relevant evidence-based practice guidelines, and the like can really make a difference. Research shows repeatedly that these kinds of reminder systems work.

If prevention is a standard of care, then health care providers should be paid to do it. A ten-minute follow-up visit with a patient who is trying to stop smoking or lose weight should be paid for. As a personal example, I just took my 16 year old daughter for a preventive checkup. Her doctor, a good one, addressed tobacco use prevention, healthy eating, and physical activity. The statement that I received from my insurance company denying payment to the doctor said that this type of prevention visit is not covered, and I am paying the highest premiums for the most comprehensive plan that I can get. Moreover, we can’t expect physicians to do all of this alone. The

culture and the organization of health care delivery could change, so that it is provided by well-trained, multi-disciplinary teams that include appropriate prevention expertise. As noted in the IOM report, prevention and early detection should be viewed as an essential part of any basic insurance benefits package. As one of the nation’s largest insurers, the federal government can take a leadership role in making this happen.

There is much that has been and can be done at the policy level. We have had remarkable successes in tobacco policy. Why not apply them to other behaviors? For example, we collect and spend taxes, and, although nobody likes taxes, there are two possible benefits. First, revenues from taxes can be used to pay for what is needed to increase access to, and demand for individual programs, such as health lines and mass media campaigns. Second, we know from careful research with tobacco that when taxes increase prices, there is a direct and significant effect on tobacco use. Fewer kids start smoking, and more adults quit. Now, with or without added taxes, revenues can be earmarked for prevention. Tobacco excise taxes can fund a national quit line infrastructure.

What to do in other areas is less clear, but some examples have been suggested. Revenues from foods could be used for subsidies that reduce prices on healthful foods. Monies collected from the use of roadways can be devoted to creating physical environments that encourage walking and biking and other activities that help us increase our physical activity levels. With regard to regulations, clean indoor air laws and regulations for smoke-free workplaces are commonplace, accepted, and also shown to lead to reduced rates of tobacco use. This approach can also be applied to other behaviors such as providing point of purchase information about the foods we are eating, so we can make more informed choices in fast food restaurants and other places. Physical activity can be encouraged as an integral part of our daily lives through requirements for daily physical education in public schools. To my knowledge, my state of Illinois is the only state in the country currently to require this.

Our continued investment in prevention research is also important. As we heard this morning, there are clearly very new exciting and important frontiers to explore in preventing cancer. But let’s be sure that as we do that we also invest in applying what we already know. For that latter goal, it is important that we evaluate new policy initiatives. There will be pockets of early adoption of innovative ideas. Good evaluation data from these early initiatives can motivate later adoption and faster diffusion. We also need to focus resources on learning more about how to get from development of effective programs to their wide-scale delivery.

I want to close with a quote from Dr. Geoffrey Rose, who said, “The knowledge that we already possess is sufficient if put into practice to achieve great health gains for all and to reduce our scandalous international

and national inequalities in health” (Rose, 1992). This quote is over a decade old. Wouldn’t it be nice if it was an anachronism in 2013?

Comments, Questions, and Answers

Leonard Lichtenfeld, M.D.,

Deputy Chief Medical Officer,

American Cancer Society, Moderator

Participant: On September 18 and 19 of this year, the National Dialogue on Cancer will convene a prevention summit to which they are inviting key leaders from around the nation, including state and local officials, community-based organization leaders, and others. They plan to develop a strategy to address systems and policy issues related to prevention. Dr. Dileep Bal, who was one of the reviewers of the IOM report, is chairing this conference. The IOM report provides a good basis for this follow-up with the National Dialogue on Cancer. So, I want to commend you, and I hope many of you in this room will come to this meeting in September. It is at the tail end of CDC’s national cancer control conference.

Dr. Byers: The key challenge that we have for the rest of the day is to be as specific as we can about what we might shift and change and grow or contract to try to reach these goals. I hope we could focus on some specifics, even if they may be a little chancier or a little wild, that will fold into the National Dialogue on Cancer summit in September in a complementary way.

Dr. Greenwald: The specifics are what I wanted to address. This report has 12 recommendations, most fairly broad, with a lot of sub-recommendations. At least half ask Congress to increase funding for something. I would like your reaction to the idea that a report like this would be more meaningful if it had priorities that were very focused with milestones and a forceful effort to achieve them. Because if you recommend everything, no matter how important, rather than focusing, you can end up with nothing.

I would like to suggest two foci. First, support Medicare coverage of preventive services through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. That could help in tobacco control, obesity control, the use of evidence-based procedures for early detection, and coverage of medical costs associated with clinical prevention and early detection. That’s one thing that would have a huge impact, and it would be great if the IOM championed it. The second focus has to do with physical activity and institutional or community behavior, which would be to encourage throughout the United States inclusion in elementary and middle or junior high schools physical activity for every child as part of their regular curriculum.

Dr. von Eschenbach: I think the first two comments raise an important issue about the theme of collaboration and integration of the various efforts and initiatives, so that we really get synergy and get major impact. Harvey Fineberg and I had a sidebar conversation about thinking ahead as to how we can integrate the report, the outcome of this conference, into many of the initiatives that are under way, some of them through the National Dialogue, some of them occurring even within the Department of Health and Human Services. I would like to see an implementation strategy that thinks about the integration piece, how it would connect to Dialogue initiatives. To make a point about the importance of that, I would like to ask John Seffrin to amplify the issue he raised in his talk about the National Dialogue on Cancer’s CEO roundtable, in which they have implemented a “gold standard” program within their corporations for provision of healthy lifestyle initiatives and early detection and screening opportunities for their employees. Although the reason for doing that is better health, there is a very significant economic piece to it as well.

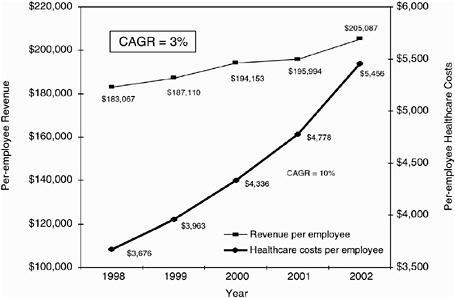

Having been a part of watching that scenario unfold, I can tell you that the scales didn’t tip until the financial analysis demonstrated that it would cost them something like $2.60 per member per month (pmpm) to implement those additional benefits. But they would experience a return on their investment of $3.00 pmpm1. There would be a net gain to the corporation of 40 cents per member per month. Now, 40 cents per member, per month is a little bit like Tim’s thinking about this as one life per minute. That net gain to them provided those corporations the economic rationale for making public health, welfare, quality of life decisions. They are implementing this plan, and it is going to save them money over time. We have to build the economic model as well as the public health model and get the alignment with the people who are essential if we are going to implement this across the board in our society.

Dr. Seffrin: This has been one of the most meaningful stories in my three-decade career. We learned from this that it doesn’t always have to be like pulling teeth when we do public health. It often means doing the right thing at the right time with the right people. The bottom line is, we went to any number of human resource directors and chief medical officers with things we thought made sense, and never could get to first base. But we began moving when we got CEOs around the table and thinking who was their

most valuable employee—their chief financial officer?—their administrator?—and thinking about losing them through premature death from cancer.

And then we went to Milliman USA2, a company we knew they respected and said you do the economic analysis. We presented those data to them, and it was a done deal. It was quite an experience to see the CEOs of major companies, employers of over eight million employees, make a commitment. We will have another meeting paid for by one of the CEOs, but he has already implemented the program, including providing reimbursement for clinical trials.

So we learn from this that sometimes we make public health more complex and difficult when we don’t push on the right buttons. We have the evidence; it is a matter of getting it in the right form and talking to the right people to get the job done.

Dr. Byers: What I would say as far as that point is that employers are important, but the employees also have certain demands, so it is a push-pull in this marketplace. I would also agree with Peter Greenwald that CMS coverage for clinical preventive services is important; in fact, coverage for preventive services across all the federal programs from the Indian Health Service to prisons to Medicare and Medicaid is important. Also employer, employee, insurance company relationships with regard to clinical preventive services are important.

But we shouldn’t lose sight of the importance of tobacco and nutrition. We need to put some emphasis on those big players; what kind of policy initiatives can we have in those areas? I also agree that our recommendations in this report are pretty general. There is a lot more specifics that we need to get to.

Dr. Curry: The concept of building the business case for this, not just within the health care system, but at the public health infrastructure level, is very important. There are many audiences, and the numbers that one audience wants, what the purchasers want to see, are not what the managed care CEOs necessarily want to see, or what the insurers want to see. I think there are some really good studies going on, and the data are out there. I am excited, to hear about the Milliman data, and I wonder if there is a way to disseminate that work; it would be incredibly helpful, because we are asked those questions all the time.

Ms. Eastman, Contributing Writer, Oncology Times. There were some mixed messages in the results from the recent prostate cancer prevention trial. There was a good message about taking finasteride, but there was concern about the grade of prostate cancer when it did develop. The general public needs things put in a simple way. So, I wonder, Dr. von Es chenbach, if you could address how you can communicate to the

public the importance of cancer prevention in a way that is not confused by the scientific complexities that are often the case when doing this kind of research.

Dr. von Eschenbach: We are in the process of closing out a negotiation for someone who will be extraordinarily effective in that role, working across the entire NCI in addressing that important problem. Often research gives us insights that themselves are quite complex, the finasteride study being one of them. Clearly, the 25 percent reduction in incidence of prostate cancer is a proof of principle and a positive finding, but the aggressiveness of the disease that was not prevented by the finasteride needs further analysis. How we communicate clearly, without resulting in what I describe as threat fatigue because of the dire messages that we keep giving to the public, is a major problem for us, and one that we will be strategically addressing and researching.

Ms. Mulhauser, Clinical Social Worker, Children’s Medical Center: Several years ago there was an effort to increase internist reimbursement for preventive services, but it was not a real successful effort. I am wondering what will happen as a result of this report that can help us approach that effort in a different way with the insurers and with perhaps a Congressional mandate.

Also, in the training section of the report, the one discipline that has the most access to low income families, social work, was not mentioned. I would advise you to think about emphasizing that and perhaps some other professions to bridge to those populations. The Institute of Medicine also had a wonderful report last May on health disparities (Smedley et al., 2002). I see some of the recommendations from that report as being very important to synthesize with this report so as not to re-invent the wheel.

Dr. Lichtenfeld: I have had experience with the physician reimbursement side, particularly with the Medicare fee schedule. We have codes for reimbursing physicians for preventive services, but they are not paid. They are not allowed or are considered uncovered services. When you go to insurers and you say a benefit will cost X number of cents per month, they respond that when that cost is applied to a million people each month it amounts to real dollars, but we will be talking more about that this afternoon. Furthermore, it is said that if every health care provider, primary care provider, devoted the time they are supposed to devote to providing all the preventive messages they are supposed to provide, it would take them around 7.4 hours on a daily basis (Yarnall et al., 2003). That is obviously not possible.

Dr. Byers: I concur with your comment about medical social workers, to the extent that is relevant to clinical psychology and dentistry and many other allied health services beyond that. I think the idea of multidisciplinary

training, not only training in multiple disciplines, but true multidisciplinary training is where we need to go.

Dr. von Eschenbach: Let me just comment on health care disparities. This year the Department of Health and Human Services at a senior leadership retreat established five strategic initiatives to focus on across the entire Department. One of the five is elimination of health disparities, and it will address specifically disparities in cancer and will be led by Harold Freeman who will be speaking to you shortly.

Dr. Fineberg: I have two comments. First, the themes that emerge when we begin probing a topic as rich as prevention of cancer ramify in a lot of directions. It is important for us to keep focus on this problem, while also remaining mindful of these wider implications. Specifically, disparities is a topic which is of not only deep significance to health and growing attention within the Department, as Dr. von Eschenbach was saying, but also the subject of a series of reports that preceded this report, the most recent prominent one being the report on unequal treatment (Smedley et al., 2002).

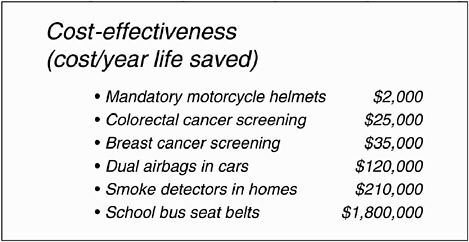

On the question of professional education, I might also reference a summit held here which produced a report on health professions education for improving quality (Greiner and Knebel, 2003), which ramifies again in a lot of directions, but which also emphasizes specifically the importance of training across the professions from a patient point of view rather than from a traditional provider point of view. Finally, on reimbursement, isn’t it notable that only with prevention do we ask that a service save money and not merely save lives? We pay for many treatments that we know will not produce net dollar savings, because we know we have to treat disease and reduce suffering. If we applied the same standard to prevention, we would be paying willingly and frequently for preventive care.

Dr. Seffrin: In addition to the Milliman data, I point you to the Lasker Foundation’s report commissioned from nine renowned economists at leading American universities (Lasker Foundation, 2000, and see also http://www.fundingfirst.org). Their conclusion was that a 20 percent reduction in cancer mortality in the United States will benefit the American economy by $10 trillion. We know how to reduce cancer mortality rates by 20 percent, so the investment, even though I don’t think it needs economic justification, can be justified on that basis.

Dr. Douglas Weed, Director, Cancer Prevention Fellowship Program, NCI: I’m glad the subject is turning to training. Dr. von Eschenbach mentioned that cancer prevention is a problem we inherited. For those here from the American Cancer Society, the academic community, it’s a moral imperative. Who is going to take this imperative into the future beyond these well established people? I do training in cancer prevention at NCI, and it is a challenge, because it involves both training and expertise in prevention. It is

critical to this effort to have people who say, yes that is what I am trained in, and that is what I am doing.

There is another group, the physicians, the nurses, the social workers, the clinical psychologists, and the epidemiologists, who participate in clinical medical practice and public health. The final group is the people themselves who believe that this is possible. I’d appreciate any reflections you have about this.

Dr. Curry: The important thing that Dr. Weed is saying is this notion of demand. We’ve talked in behavioral medicine about a framework of push-pull, where there is the scientific evidence and capacity providing the push. You also need the demand for this to happen. The kinds of changes and investments that health care systems will make in response to patient demand are amazing. Complementary and alternative medicine, much of which do not have the evidence base that we have for prevention, are in high demand, and they end up becoming a part of what patients can receive. It is part of the imperative to legitimize on the part of the American public that if your physician and your health care providers are not addressing prevention, you need to demand it.

Dr. Byers: We need to train individuals so that professionally and ethically they are motivated to spend a lifetime career in prevention. In terms of the institutions, it has to be collaborative across a number of them, NCI, CDC, ACS, and the like. One of the important questions that the National Dialogue on Cancer has to grapple with in its September meeting and beyond is—where is the leadership to make sure that is done?

Dr. von Eschenbach: Maybe there is an opportunity here. Secretary Thompson has been stressing this issue. Maybe, he and the Surgeon General can provide some additional visible leadership on this to get us where we want to go.

Mr. Bill Corr, Executive Director, National Center for Tobacco Free Kids: Dr. Fineberg began the meeting with a very important statement when he said that the work of this excellent report isn’t done until we implement its recommendations and actually have done something about it. The report captures so well all we know about tobacco control, all the proven solutions that we have implemented in places around the country. In my personal travels, I find that many elected officials, state legislators, local city council people, and many federal officials, do not know that we have proven solutions to reduce initiation of tobacco use and to help people quit. We have to find more creative and more effective ways of communicating the kind of information that has been compiled in a way that is real to our elected officials. Dr. Byers mentioned the California and Massachusetts tobacco control programs that have had great success. The Massachusetts statewide prevention and cessation program has been cut in the last year from $48 to $2 million, and it may end up with nothing in its current cycle.

I realize that we have a huge deficit, but here we have a proven solution that will save lives and reduce costs to the state. Yet it gets on the cutting block very, very quickly. Across the country, while many programs have been cut, tobacco control programs have been cut disproportionately. I’m not quite sure why or what is behind it, but I know that we have to get elected officials to understand and appreciate what you have compiled in this report. I would urge us to think of ways, creative new ways to get this information out in front of our elected officials.

Dr. Curry: You make an excellent point, and I don’t have an answer for it. But while I was on the National Cancer Policy Board, and while this report was in progress, we released State Program Can Reduce Tobcco Use (IOM, 2000). There were master settlement funds then that were being infused into states. The CDC has a wonderful document that described the ideal program, and we wanted to contribute to that effort. We sent copies of this report to every state legislature, but I haven’t met a person yet who knows that the report existed. So, I do think that we are challenged to come up with creative ways to do this.

Reducing Disparities in Cancer

Harold Freeman, M.D.,

Director, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities,

National Cancer Institute, Medical Director,

Ralph Lauren Center for Cancer Care and Prevention

I’d like to begin my remarks with a personal comment. I have spent my career in Harlem, New York, a place that former Mayor Jenkins called the village of Harlem, and it is a village. The things that I have accomplished in this line of work reflect my 35 year experience as a surgical oncologist in Harlem, a community of people who are 41 percent poor, heavily black, and more recently Hispanic, but minority in general, and who have a set of the worst health indices seen in the world. Indeed, in 1990, a colleague and I wrote a paper called “Excess Mortality in Harlem” in the New England Journal of Medicine (McCord and Freeman, 1990), that reported that a black male growing up in Harlem had less chance of reaching age 65 than a male growing up in Bangladesh, a third world country.

Superimposed on that experience, I have had the opportunity to advance to national positions that have allowed me to look at the entire nation. For example, as the national president of the American Cancer Society in 1988–1989, or for a number of years as chairman of the President’s Cancer Panel, I could look both ways, big, broad, but probably always through the lens of

my local personal experience. So, I am going to talk to you about some of that today.

Over the years, there have been important reports that have dealt with the issue of disparities. In 1989, the American Cancer Society report on cancer in the poor (American Cancer Society, 1989) found from the poor that spoke at hearings that they had difficulty in getting through the health care system; even with cancer, there were barriers to getting through the system. They told us that they made sacrifices in trying to get health care, like losing jobs, losing automobiles, losing dignity. They told us that the educational system in America, they felt, was irrelevant and insensitive to them so many times. They told us that they had more pain and suffering and death due to cancer because of late diagnosis. They told us that ultimately they become fatalistic and gave up hope. For this knowledge base, this was a major turning point which came from the American people themselves. Tim Byers said that epidemiology is data with the tears wiped away. At those hearings, the tears were there. So somehow we have to put together the epidemiological findings and the real experiences of the American people to try to understand this disease.

Then there were two major IOM reports, one in 1999 (Haynes and Smedley, 1999) and one in 2002 (Smedley et al., 2002), Unequal Burden and Unequal Treatment. We are standing in that institution now. I won’t go over those, except to say that they brought all of the known literature together and drew conclusions, looking mostly at black and white comparisons, that there is an unequal burden of cancer in black Americans in comparison to other populations, and there is also unequal treatment, which is a different issue.

Then we had the Healthy People 2010 report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000), Voices of a Broken System, from the President’s Cancer Panel, (President’s Cancer Panel, 2001), and the initiative that Andrew von Eschenbach mentioned, the Health and Human Services Secretary’s initiative on eliminating health disparities (http://www.raceandhealth.hhs.gov), which is one of five major goals for this Administration.

Traditionally, we look at causes of death by disease or condition, and cancer is the second most common cause. But there is another way to consider actual causes of death as McGinnis did in his 1993 paper (McGinnis and Foege, 1993).The “real” causes of death, as he stated from CDC, are somewhat different. Tobacco becomes number one, poor diet and lack of exercise number two, alcohol number three, followed by infectious agents, pollutants and toxins, firearms, sexual behavior, and so forth (see Dr. Seffrin’s Figure 2). So this is a different way of looking at the causes of death, and perhaps gives a road map for action. You can say heart disease and cancer, or you can say tobacco and diet.

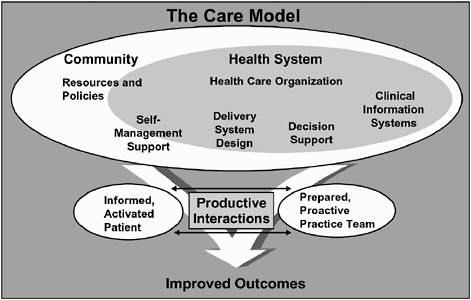

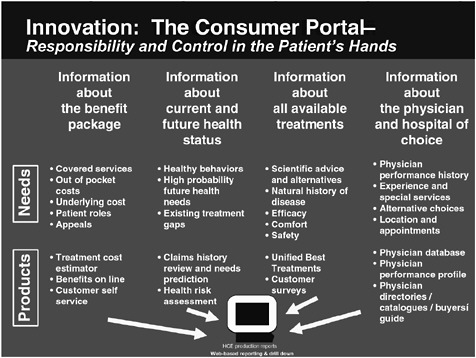

We believe at our center, the NCI Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, that the lesion is the critical disconnect between discovery, development, and delivery. This is what I call the pathological lesion that results in disparities. The discovery-delivery continuum, which Dr. von Eschenbach speaks about a lot, needs a lot of attention. The engine for everything is discovery, naturally, and then it has to be translated. But finally, it must be delivered. To the extent that we fail to deliver both knowledge and access to populations in America, that is what creates disparities.

We don’t have time to go deeply into the causes of disparities, but there are three overlapping causes—low economic status/poverty, culture, and social injustice; they seem to me to be probably not all, but certainly much at the root of the problem. Low economic status and poverty, overlapping with culture, which is not necessarily a negative or a positive, but lifestyle, attitude, and behavior are very important, and then the element of social injustice, brought out in the unequal treatment report of the IOM in particular, overlaps as well. My sense is that these three factors are major causes of disparities and that they may overlap to different degrees at different times in the history of our nation. There have been times when social injustice was the biggest; we had 350 years of slavery in this country. That is diminished, comparing 2003 with 1700, but, still, the factor is there.

Culture, lifestyle, attitude, and behavior—whether you smoke, your diet, among others—comprise a critical set of issues. Data were shown today illustrating the fattening of America. This was shown the last couple of days by the CDC Director as well, how fat we have become, and 20 percent of cancers are said to be related to the factors of obesity and diet. Then there is the issue of poverty and economic status. Notice that race is not in this picture; it is mostly in the sphere of social injustice, where race has an effect.

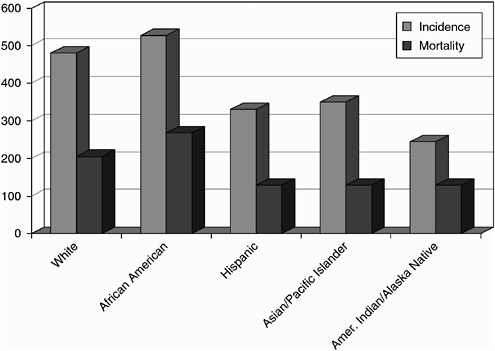

Life expectancy tells the story in a different way. In the end, it has to do with who dies and who lives in America. If you look at population life expectancy according to sex and race, here is the pattern. Black males—65 years, white males—73 years; black females—73 years, white females—78 years. We need to understand whatever is happening to create these differences. I do not believe that being black in and of itself causes people to live or die. I think it is the life circumstances that make the difference. It is clear to this audience in particular that some groups don’t do as well as others. We need to define who those groups really are, and try to understand the real variables that are causing disparities, and not just simply be satisfied to say it is black and it is white. I don’t think that is the best way to understand disparities. If there is a population that is black that is also disproportionately poor, that would overshadow that it is black, for example.