Achieving XXcellence

Diane Wara, M.D.

University of California–San Francisco

SPEAKER INTRODUCTION

SALLY SHAYWITZ, M.D., CHAIR, AXXS STEERING COMMITTEE

Dr. Wara is associate dean for minority and women’s affairs at the University of California–San Francisco. As a key member of the chancellor’s advisory committee on the status of women, she guided the passage of a number of faculty changes, including the statewide University of California policy on child-bearing and child-rearing leave. Dr. Wara is division chief of pediatric immunology and rheumatology and program director of the pediatric clinical research center. She is also an expert on abnormalities of the immune system in children, has a primary interest in AIDS, and has published extensively in this area.

DR. WARA:

I wear two hats here. I’ve just completed 12 years as the associate dean for women and minority affairs at UCSF, with fairly heavy involvement at the Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC] during that same time period. As well, I’m a clinical investigator. I tried to put those two hats together in fashioning a fairly brief summary talk that will contain these four components: What is clinical investigation, because that is what we’re here to talk about? Are women faculty in schools of medicine advancing? I will then offer a personal perspective. I finish by asking how can professional societies enhance the development of careers for women in clinical research?

Clinical Investigation—What Is It?

What is clinical investigation? If one takes just the middle component of Karen Antman’s notion about what do we do at academic institutions—the first being laboratory-based investigation, the second clinical investigation, and the third outcomes-based and epidemiological research—then clinical investigation in the middle implies that a doctor is in the same room with the patient. That definition was put forward by three different groups, including the Nathan panel that met four or five years ago at the National Institutes of Health [NIH]. By the way, having the doctor in the same room as the patient has some fairly heavy implications for the investigator.

Over the last decade the faculty in clinical investigation has decreased by about two-thirds—not the senior people who were well established, but the junior people coming in and moving up as clinical investigators. The problem, if you will, begins during medical school when clinical investigation is not discussed very thoroughly. It then moves on into residency where we really don’t spend a lot of time with them talking about clinical investigation. Those young residents in decreasing numbers have been choosing to enter subspecialty fellowship programs. During that time, a few are snared; we do glean some clinical investigators through our fellowship programs. But there’s been a significant falloff.

The data come from three separate reports during the 1990s.1 The first was published by the Institute of Medicine in 1994. The second is the Williams report published in 1995 (I was a member of the Williams panel). Gordon Williams and some of my colleagues in this room from the National Institutes of Heath, as well as some of us from academic institutions, looked at the grant funding at the NIH. We asked ourselves what was good and was directed toward clinical investigation, was there enough, and was it in the right proportion for different issues. And we made suggestions, most of which were followed. Finally, there was the Nathan report, published in 1998, which advanced both the IOM and the Williams report and put forth solid recommendations to the NIH.

The data from these three groups were consistent across the groups. So what’s happened? Since the Nathan report, the dollars at the NIH have increased by about one-third for clinical investigation. That includes all the mentor career development awards that we’ve heard about today, which really are aiming at the crux of the problem: how to bring more young investigators, both men and women, into clinical investigation. The answer is to provide structured mentored

career development awards as bridge dollars at the end of a young person’s fellowship or at the beginning of her academic career, and before she should be expected to compete for R-01 grant support. Ideally, there should be about five years of bridge dollars.

Study sections actually have been changed, although quite modestly. Some study sections have had the Gordon Williams golden rule imposed. I had the great job of reviewing for one calendar year the abstracts from every NIH grant submission if either “I” or “B” or clinical investigation was checked on the front sheet. When we looked at those abstracts and then asked how many of these grants were funded versus the priority scores or ranking of those grants by a study section, we learned (and we published in the Journal of the American Medical Association) that grant applications were much more likely to have a good and fundable priority score if they were reviewed by a study section that included at least one-third peers. For clinical investigation that meant that one-third of the study section should be or have been intimately involved with clinical investigation.

The NIH took that finding to heart and changed about 20 percent of its study sections. The result is that grant applications that move through the modified study sections, which have a larger number of clinical investigators, do better. In other words, applicants for clinical investigation do better if they’re reviewed by their peers. That’s simple.

The difficult part has been figuring out how one coerces enough faculty from our academic institutions to fill out one-third of the study section slots in the appropriate study sections. So I recommend that societies strongly encourage their members to participate actively in study sections. When asked, don’t say no, because it’s really where our dollars, our future comes from.

So study sections were changed, and that was good. However, women in clinical investigation and their unique needs were not truly addressed. Men and women have the same startup issues, and they have the same mentoring issues. But there is a difference between a young woman and a young man entering clinical investigation in academic medicine. Two of the major issues have been mentioned. The first is that whether we like it or not, agree with it or not, raising our children and caring for our parents remain primarily a woman’s job. Therefore, the impacts of those two care-providing jobs—I would say privileges actually, rather than jobs—fall on women. How to make that work for a young, mid-level woman clinical investigator remains an issue that we must address.

Second is an issue that no one really likes to talk about, and so I was pleased to see it listed: clinical investigators often are second-class citizens. The need for good to outstanding clinical investigators to work across disciplines, to be collaborative, to be the middle author on some publications, also is not discussed a lot. Our women’s collaborative natures are, from my perspective, a benefit and a huge joy, but that particular aspect of our work is undervalued, and that needs to be addressed and corrected.

Now I want to move to Goldstein and Brown and a publication that I recom-

mend to all of you and particularly love. In June 1997 Drs. Goldstein and Brown of cholesterol and Nobel laureate fame published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation a paper entitled “The Clinical Investigator: Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered but Still Beloved” that describes clinical investigators and clinical investigation.2 It is a joy to read. According to Dr. Goldstein, these investigators are bewitched by the thrills of science (meaning laboratory-based investigation) and medicine (meaning the care they provide to patients), bothered by the need to choose one over the other, and bewildered by the need to choose.

They further posed a diagnosis that they called PAIDS. I’ve always thought of PAIDS as “pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.” But Drs. Goldstein and Brown used PAIDS to refer to the “paralyzed academic investigators disease syndrome.” They posited many of the same issues that have been discussed previously.

First, there is a knowledge gap between medical school and a research career, which in the context of this article is a career in clinical investigation. The knowledge gap is that a set of tools is required for laboratory-based investigation. Few of us have admitted until recently that an equally complex set of tools is demanded for the conduct of clinical investigation. Again, the National Institutes of Health are to be commended for their K-30 and K-12 awards, which are allowing some of our institutions to provide training in this area. Now we have to give our junior faculty release time to acquire these skills.

We all know that it is difficult to combine research with medical practice. Yet the conduct of clinical investigation implies direct interaction with patients, and it implies ongoing clinical practice. But then there are the economic disincentives. The debt load averages $80,000 for everybody who finishes medical school. But that’s crept up, and by now it’s probably over $100,000.

Drs. Goldstein and Brown say that four P’s can be applied to patient-oriented research, or POR. The first is Passion—all of us are fairly passionate about our clinical investigation. The second is the Patients we care for and the patients for whom we define new therapies within our clinical investigation. The third is Patience. We’ve heard today that it takes a long time for a specific question posed within the context of clinical investigation to come to fruition. Goldstein and Brown say it took them eight years before they had anything meaningful they could translate to patients. And the fourth is Poverty. This does not mean personal poverty. It means grant dollar poverty, which has been somewhat remedied.

Moving Women into Leadership Positions

We know that women face many more challenges than men in obtaining career-advancing mentoring. We also know that men have difficulty effectively mentoring women. Men need some education, and, from my position, women do

too. There are just as many poor women senior mentors as there are poor men senior mentors. Senior women often are not leading the same lives and have not led the same lives as the junior women coming along. Senior women must then—and so must men—be very open and receptive to the changes in society and the increasing complexity of society if they’re going to be good mentors.

Isolation reduces a woman’s capacity for risk-taking, often translating into a reluctance to pursue professional goals or a protective response such as perfectionism. Why is risk-taking important, and why is it mentioned here, and why will I mention it later? I have a personal view that we make progress through taking risk. We make progress in terms of enhancing women’s careers by taking risks at our institutions and nationally. We make progress in our research by going out on a ledge, asking questions that are not easy to answer. It’s difficult to take risk if one is in isolation. If one has peers next door, down the hall, or in my case across the country to communicate with, it’s easier to take risk. I find that although I’ll be taking a risk, I can check with someone else that it’s not necessarily a stupid risk. It’s a good risk, a risk that will energize me and others, and a risk that will result in change and innovation. When women or men are isolated at any level—then risk-taking is diminished.

Without being conscious of their mental models of gender, both men and women still tend to devalue women’s work and to allow women a narrower band of assertive behavior. The AAMC Increasing Women’s Leadership Project Implementation Committee examined four years of school-provided data. Every institution receives a benchmark survey that’s compiled annually by the AAMC. It includes interviews with department chairs across the country, both in clinical and in basic science departments, and it includes new research from industry and higher education on women’s achievements and advancement.

The key findings are that women comprise 14 percent of tenured faculty, 12 percent of full professors, and 8 percent of department chairs in the United States and that very few schools, hospitals, or professional societies have a critical mass of women leaders. Moreover, the pool of women from which to recruit academic leaders remains shallow. I have to say that every time I present this, I’m told by my male colleagues to stop using the word shallow. Shallow can be interpreted in many ways. The pool does not necessarily include shallow women; it’s just that the pool is not very deep.

How can we fix that? I believe we can fix it by working together and by generating a centralized pool that’s easily accessible, so that when a great position is available, we can propose to the committee a group of women candidates who are serious candidates. But that list of candidates should not come just from our own list of preferences, but from a central pool of women who have said they are interested, they are prepared, they are academically viable.

According to AAMC data from 2001, 46 percent of new entrants to U.S. medical schools were women, and women were the majority of new entrants at 31 schools. At the level of residents or postdoctoral fellows, 38 percent of resi-

dents were women, with the highest proportion, 70 percent, as you might guess, in obstetrics and gynecology and 65 percent in pediatrics. A much lower proportion of women were in most surgical subspecialties such as urology, 12 percent; neurosurgery, 10 percent; orthopedic surgery, 8 percent; and thoracic surgery, 6 percent. So there’s an uneven distribution of women entering the subspecialties and much work is left to be done. At the faculty level, 28 percent of all faculties were women, but only 12 percent of full professors were women.

The AAMC graph presented earlier by Janet Bickel (see Figure 3, p. 39) shows that the slope for medical school graduates has increased fairly consistently since about 1980. There are some little blips, but they’re not substantial. On the other hand, the percentage of women faculty, which is now 28 percent, went up fairly rapidly during the late 1980s and the early 1990s, but it has leveled off and the slope is not nearly as steep as it was. To analyze the slope of that curve and the alteration in it, we need raw data that neither I nor the AAMC have.

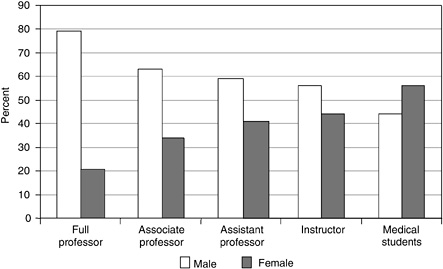

And where are all the women faculty positioned? In 2001, 11 percent of all women faculty were full professors, 19 percent were associate professors, and by far the majority were at the beginning of their careers—50 percent of women faculty were assistant professors and over 17 percent were instructors (see Figure 4, p. 40).

So where should the academic societies focus their energy? If we’re going to move women into leadership positions—meaning deans, chairs, division chiefs—we probably want to be working at the juncture between associate and full professors (Figure 4). But if we want to plan for the long haul, in a decade from now, we want to be working at the transition from assistant to associate professors. That’s a charge I would make to the societies—to nurture, mentor, and work with the junior faculty in order to bring them along and be as certain as we can be that they’ll be successful.

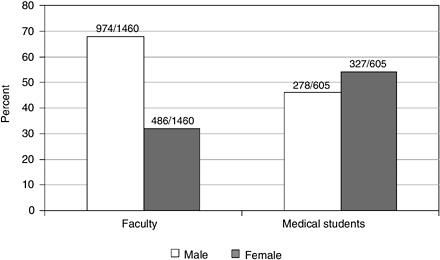

The data from my own school are not a lot different from anyone else’s (Figure 5). The real reason for showing this is that we mark it against the AAMC benchmark data every year so that our chairs and deans are very aware of where we are doing well and where we are not doing so well. In 2001, 327 of our 605 medical students, or 53 percent, were women. We’re very proud of this number. On the other hand, only 33 percent of our faculty, 486 out of 1,460, were women. This is higher than the AAMC data, but not good enough for an institution that’s put a fair amount of resources into bringing women into the system and nurturing them, retaining them, and advancing them.

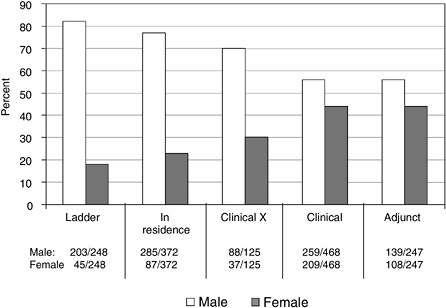

Where are these women at UCSF? Of all the full professors, 22 percent are women (Figure 6). Like on the AAMC national grid, the majority of women faculty at UCSF’s School of Medicine are assistant professors or instructors, and, of course, the largest percentage are medical students. But let me emphasize that the research faculty are there. At UCSF only 125 of the 1,400 School of Medicine faculty are in a clinician educator series; about 700 are in the clinical and adjunct series (Figure 7). Few women are in the prestigious series; they sit in the less

FIGURE 5 Gender distribution: full-time faculty versus medical students, University of California–San Francisco School of Medicine, 2001.

SOURCE: Unpublished data of the author.

FIGURE 6 Gender distribution within faculty ranks and medical students, University of California–San Francisco School of Medicine, 2001.

SOURCE: Unpublished data of the author.

FIGURE 7 Gender distribution within series, University of California–San Francisco School of Medicine faculty, 2001.

SOURCE: Unpublished data of the author.

prestigious series. We at UCSF are not unique, but now we have women in the assistant professor and instructor ranks in the less prestigious series. Although I would love to be able to say five years from now that these are not less prestigious series, I don’t believe we’re going to move everyone in this direction. What we do need to do is value everyone for what they contribute.

Our initiatives to support women’s progress have included mentoring programs. We have a mentorship faculty handbook, and we have a mentor-of-the-year award. What we have not done well is to develop family-friendly policies. Sue Shafer just co-chaired a climate survey at UCSF, which showed very clearly that both men and women were quite reasonably happy, over 60 percent happy, with their lives as academics at UCSF. But they were not happy about the absence of what are now termed family-friendly policies, including child-bearing and child-rearing policies, and the paucity of part-time positions “with a future” (one can work part time at UCSF but one doesn’t necessarily have a future). Our faculty members also don’t like that we do not have a day that actually begins and ends—our day is just a continuous cycle of 24 hours. And we don’t have adequate elder care, which was sorted out in the climate survey and was noted as a weakness.

Although we do, I believe, have salary equity, it has not been institutionalized. Throughout this workshop I’ve heard both junior and senior faculty commenting on the perception that women are not paid equitably. To prove or disprove that and to make change, we have to institutionalize salary equity, meaning a database that can be checked twice a year with a variety of controls in place. We have to focus on retention, and we need to change our search committees for leadership and for all positions.

As for search committees, we need to bring women to the table. We have to get our leaders and search committees ready for women, and that means beyond tokens. We have to improve the search process, which in my mind means going beyond the research CV, increasing the emphasis on diversity, placing two to three women on each search committee. That implies all of us have to do more work, and when we’re asked to serve on a search committee, we must say yes if we agree with this premise.

Finally, we need to avoid the reflecting pool method of hiring—that is, recruiting, hiring, and putting people on the short list who look just like the men on the search committee or perhaps even like me on the search committee. We need to look for people who have new ideas, who have new visions, and who are different from us. We have to request the reasons when the short list for any search committee does not include women or minority candidates.

Personal Perspectives

Clinical investigators are hybrids. I mentioned that they require skills both in the laboratory and in the clinic. They bring two worlds together and through their research give enhanced meaning to laboratory findings. What good is the human genome—all that work, all that money—if it’s not correlated within the next five to ten years with the phenotype? Do my patients care if I can’t explain to them the genetic basis of their disease or explain to them why a particular drug works differently for them than it does for the next person? So we need to move to importance, which is what has been done so beautifully in the laboratory over the last decade.

However, this clinical work implies patient demands. Night call and weekend call—it’s another layer of complexity. I have no solution for this, by the way. Both academic medicine and society at large are much more complicated now than 20 years ago. I actually believe that raising my two children, who are now 29 and 33, was a lot easier than the job given to my young women colleagues.

Finding time to sustain and build both one’s personal life and one’s professional life is increasingly difficult. Speaking for myself and for my family, there are not enough hours in the day to care for aging parents (I cared for four of them over the last decade), to retain the solid friendships outside of academic medicine, to have space—here’s that risk-taking thing again—for the necessary risk-taking that makes it all fun, to build skills (I like to think I’m still building) in clinical

investigation, and to mentor others. That’s a large platter, and there really needs to be room for all or at least most of it.

Then there’s my daughter’s wedding. She is working for Northern California Kaiser in obstetrics/gynecology, and so she has a lot of night call and weekend call. Because she’s getting married next month, she and I talk every night about how we’re going to divide up the jobs, because both of us have these very busy schedules. So it doesn’t end; it just keeps going on and on. It’s joyful and delightful, but there are problems for women that I believe are not there for men in balancing all of this.

The three-legged academic school of research, teaching, and community service does have a fourth leg: clinical responsibility for clinical investigators. One more thing, it’s lonely at the top. As the MIT report on the status of women faculty said, and I thoroughly agree with it, marginalization does increase as women progress. At every institution there are too few senior women clinical scientists to form an effective cohort. So my mentors and my colleagues are people I work with nationally. I met them and work with them continually through the pediatric AIDS clinical trials group, through the pediatric primary immunodeficiency network, and through my societies.

Societies

What can societies do? Societies should be a forum for leadership. They should develop leaders

-

through appointing women and men committee chairs, but they need to focus on women—they must

-

through achievement awards—we should be nominating everyone who’s eligible for research and achievement awards

-

through session chairs—we need to be certain that women are session chairs and that they’re junior women, because we want to nurture that large pool of women who are at the entry level

-

through more data and best practices.

For career development, I like the notion of mentoring and mentoring awards. I like the notion of working with advancing women, of workshops for women within the context of society meetings. I especially like the notion that we should provide a mechanism for interaction between mid- and senior-level women to maintain ongoing networks. It’s not just junior women who require the networking; it’s all the way up to the top.

One society, not a clinical society, that I’m actually a member of, as are many people in this room, has done quite a good job. The American Society for Cell Biology [ASCB] has had women in the cell biology group since the mid- to late 1990s. The committee has a whole panoply of interactive and interesting

pieces on the ASCB Web site [www.ascb.org], including AXXS ’99. And they have a monthly newsletter that has become a standard at UCSF. Our active women in cell biology members forward it to us by e-mail, so that we’ll all pay attention to it.

Today is an ideal time for societies to work toward the enhancement of career advancement for women in academic medicine and for women in clinical investigation, because the current environment, through the NIH, is providing unique support for young clinical investigators. It really positions professional societies to enhance women’s careers in a way that I have not seen since the early 1970s. The dollars are there, and the women are in the door as assistant professors. It’s a unique moment, and we should capitalize on it and perhaps just take a little risk and go ahead and do it.

Closing Remarks

Vivian Pinn, M.D.

Director, Office of Research on Women’s Health

Associate Director, Research on Women’s Health

National Institutes of Health

I want to begin by thanking Sally Shaywitz and all of you for your participation and helping to make this workshop successful. Many viable, innovative, and wonderful suggestions have come forward. Perhaps the most exciting results of this meeting, something that I enjoy every time I go to a meeting like this one, are the new interactions, new friendships, and new avenues for networking that have been established. Our speakers have all been marvelous.

As I listened to the recommendations, I liked hearing what we’ve all recognized—that societies can be and should be agents for change, and we want to facilitate that. We want them to be agents of change in the professions, in health careers, and in research careers for the entry and advancement of women—not only in the basic sciences, not only in medical sciences, but also in the clinical sciences. If we focus on our interdisciplinary collaborations, interdisciplinary research, and interdisciplinary career development, we will continue to ensure that our efforts are interdisciplinary in nature, spreading across not just the medical discipline but all of the other clinical disciplines, as well as basic science and perhaps traditional and nontraditional other areas through which women contribute both as basic scientists and as clinical scientists.

I liked some of the specific recommendations that were put forward. I heard three major things. The first was how to facilitate professional society meetings as a way to bring to the floor specific recommendations that would address the women who are members of those societies.

Second, as Dr. Pardes put forward, we need to bring together a panel on clinical research, including deans of medical schools and heads of medical centers, representatives of the NIH, and representatives of industry. We have heard people speak about the role of industry, but how do we add industry to the mix in

terms of facilitating the advancement of women in biomedical research careers? Also, how do we get professional societies involved?

We will work with the Committee on Women in Science and Engineering and the National Academy of Sciences, because we feel this is a wonderful way to undertake a meeting that both has credibility and puts in correct focus the particular topic we want to address. So we will work very closely to see if we can fund just such a meeting in the coming year. It is hoped that we can take all the recommendations contained in the report of this meeting and then see where we can go in terms of bringing together the leaders in the research community. It’s not just societies that are the agents of change, but also those who are in positions to be agents of change within the academic community, the academic health center community, the professional society community, and the NIH community.

Third is something that I thought was very important: being able to track progress, as Dr. Shaywitz and many others mentioned. We’ve heard accounts of individual institutions and individual societies. But how can we measure whether these activities and your participation are making any difference in your own professional societies? We’ve heard reference to things such as report cards; in fact, we heard that at AXXS ’99. So should there be report cards for professional societies? Or are there better ways or other ways to track the impact of these kinds of meetings and discussions on efforts to increase activities to support women scientists among the different professional organizations?

I don’t have the answer, and I didn’t hear the answer from you. I did hear a call for a way to do that. So that’s something else we need to pursue—how to better track the impact of these kinds of discussions. I have learned from my experience, and I’m sure you’d agree, that if there’s a way to track the progress, there’s more apt to be progress—that is, when someone knows that you’re going to look closely for accountability about what has occurred.

Mentoring is something that again is central to almost everything that our office continues to focus on. I also have some ideas about many of the recommendations that I heard today, including looking at how to gain a forum at professional society meetings. I don’t know that we could fund every society meeting that has a forum or a session on grant writing for women or on how to promote women’s careers, but we ought to be able to do that for some number. I’m going to ask our careers committee to take a look at what we can do. We have funded a small number in the past, and perhaps we can come up with some way to at least be able to support some societies.

In closing, I want to thank you by making a commitment to take forward as best we can as many of the recommendations that you made that are appropriate for us to fund or that are appropriate for us to pursue. I promise you we will do that in gratitude for your effort.