4

Case Studies of Adaptive Management

This chapter reviews some of the Corps’ initial efforts in implementing adaptive management principles, most of which were initiated during the mid-1990s. These case studies include the Florida Everglades, the Missouri River Dam and Reservoir System, the Upper Mississippi River, and coastal Louisiana. A case study of the Adaptive Management Program at the Glen Canyon Dam and Colorado River ecosystem, in which the Corps is not involved, is included for comparative purposes, as there is a relatively long record of applying adaptive management principles to managing the Colorado River. A case study on the Columbia River, the site of one of the earliest adaptive management applications in a large U.S. river system (Lee, 1993), was considered but not included. Although the Corps has responsibilities for navigation and dam operations on the Columbia River, it has had only a relatively small role in formal adaptive management efforts, which mainly involved the Northwest Power Planning Council (renamed the Northwest Power and Conservation Council in 2003) and federal and state resources agencies. The settings of these case studies vary in terms of spatial scale, biophysical features, inter-agency relations, economic activities, and stakeholder preferences. Lessons from experiences in this breadth of settings may reveal general principles regarding potential barriers, useful management actions, or inter-agency relations that merit consideration in establishing and managing adaptive management programs.

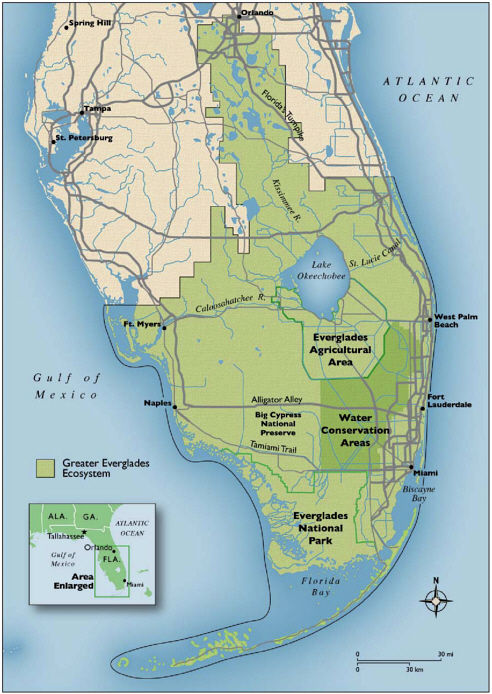

FLORIDA EVERGLADES

The Everglades ecosystem (Figure 4.1) stretches from Florida’s Lake Okeechobee southward to the Florida Reef Tract. The pre-settlement ecosystem featured the slow movement of surface waters to the south and the west, which eventually emptied into the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. This low-relief, marshy ecosystem is often referred to a

“river of grass,” a term coined by Marjorie Stoneman Douglas in her famous book on the Everglades ecosystem. Her book was published in 1947, the same year Everglades National Park was established. The ecosystem experienced significant human-caused alterations as early as the mid-eighteenth century, when parts of it were drained to promote agriculture and settlement. In 1907 the Everglades Drainage District was created (Blake, 1980) and by the early 1930s, 440 miles of drainage canals had been constructed in the Everglades (Lewis, 1948). Concerns about ecological degradation of the Everglades were raised as early as the 1920s, and by the time Stoneman wrote her book, the ecosystem had been extensively altered. These ecological changes continued in the late 1940s, when huge floods in 1947-48 across south Florida led Congress to establish the “Central and Southern Florida Project for Flood Control and Other Purposes.” This initiative led to accelerated ecological changes in the Everglades, as the project entailed levees, water storage, improvements of conveyance channels, and large-scale pumping to supplement drainage. All these projects helped channel water away from the Everglades in an effort to reduce floods, support agriculture, and promote settlement. The project also entailed the construction of a 100-mile perimeter levee separating the Everglades from coastal urban development. These hydrological changes were substantial and have been linked to, for example, declines in avian species and the listing of dozens of animal and plant species as federally threatened or endangered.

In response to these declining ecological trends in the Everglades, the federal Water Resources Development Act of 1992 authorized a comprehensive review of the Central and Southern Florida Project. In 1993, the Corps of Engineers and the South Florida Water Management District began a Comprehensive Review Study (known as the “Restudy”) to determine the feasibility for modifications to improve the sustainability of South Florida (USACE and SFWMD, 2002). The Restudy led to publication of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP), a document that was approved in the Water Resources Development Act of 2000. Congress approved the comprehensive plan with an estimated cost of some $7.8 billion (1999 dollars) as a framework for planning projects to restore a major portion of the historic Everglades, including Everglades National Park, while meeting other water-related needs (e.g., water supply, flood management) of South Florida through 2050. In approving the plan, Congress included adaptive management (referred to as adaptive assessment) as an authorized activity, at a cost of $100 million, and provided for a 50/50 split of these costs between the federal government and the State of Florida. This authorization is notable for two rea-

sons. First, adaptive management was recognized explicitly as a water management approach for the first time in a civil works project authorization. Secondly, the Corps was authorized to share in the costs of all operations and maintenance costs of CERP, including the costs of "adaptive assessment and monitoring."

The Comprehensive Restoration Plan was developed by the Corps of Engineers in partnership with the South Florida Water Management District, and with participation of several federal and state agencies and extensive public and stakeholder involvement. Its purpose is “to restore, preserve, and protect the South Florida ecosystem while providing for other water-related needs of the region, including water supply and flood protection (WRDA 2000, Title IV, Section 601(b), Public Law No. 106-541).” The plan is to be implemented to ensure protection of water quality, restore some degree of pre-settlement hydrologic conditions (including reductions of freshwater flows to several estuaries), improve environmental conditions of the South Florida ecosystem, and achieve and maintain benefits to the natural and human environments (as described in the plan) for as long as the project is authorized (http://www.evergladesplan.org; accessed January 28, 2004). The plan is designed to provide over 1,100,000 acre-feet of additional water annually to the environment and human uses. About seventy percent of the water would be devoted toward environmental objectives, and the remainder would be devoted to economic purposes—largely for domestic use by the additional six million residents expected to inhabit the region served by the project by 2050 (USACE, 1999).

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan is not based on a traditional Corps feasibility study, but is largely a conceptual plan encompassing 68 individual projects. Major components of the plan involve sophisticated technical aspects, including large-scale use of aquifer storage and recovery for multiyear subsurface retention of captured surface water (NRC, 2001a), and subsurface seepage barriers to prevent loss of the captured water to the system as it is being stored and delivered (these techniques are not well-tested on this scale). Because of the plan’s size and complexity, it will take many decades to implement, and congressional authorizations to construct and operate the plan’s major elements will depend upon submission of detailed feasibility-level studies for individual projects. Additional modeling and design is underway to provide detailed project recommendations, and pilot projects are being developed to address technical uncertainties. Adaptive management will be critical to the plan’s evaluation and improvement. Key aspects of the

plan include additional water storage and water supply, improved water quality, and increased connectivity within the components of the hydrologic system. These features include more natural hydropatterns, including wet and dry season cycles; natural recession rates; surface water depth patterns; and, in coastal areas, salinity and mixing patterns characteristic of the natural system.

Adaptive Management in the Restoration Plan

The Programmatic Regulations for the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan contain definitions regarding adaptive management within the plan:

Adaptive management means the process of improving understandings of the natural and human systems in the South Florida ecosystem, specifically as these understandings pertain to the goals and purposes of the Plan, and to seek continuous improvement of the Plan based upon new information resulting from changed or unforeseen circumstances, new scientific or technical information, new or updated models, or information developed through the assessment principles contained in the Plan, or as future authorized changes to the Plan are integrated into the implementation of the Plan.

Assessment means the process whereby the actual performance of implemented projects is measured and interpreted based on analyses of information obtained from research, monitoring, modeling, or other relevant sources (68 Fed. Reg. 218, 64,199-64,249).

According to the proposed regulations, the purposes of the adaptive management program are to: (a) assess responses of the system to implementation of the plan; (b) determine whether or not these responses match expectations, including the achievement of the expected performance level of the plan, the interim goals and the targets for achieving progress towards other water-related needs of the region provided for in the plan; (c) determine if the plan, system or project operations, or the sequence and schedule of projects should be modified to achieve the goals and purposes of the plan or to increase benefits or improve cost effectiveness; and (d) seek continuous improvement based upon new in-

formation resulting from changed or unforeseen circumstances, or new scientific or technical information. Adaptive management activities are to be carried out by interagency and interdisciplinary scientific and technical teams organized under the Restoration Coordination and Verification program, or RECOVER (http://www.evergladesplan.org/pm/recover/recover.cfm; accessed January 28, 2004). These teams are established by the Corps of Engineers and the South Florida Water Management District to assess, evaluate, and integrate projects, with the goal of achieving system-wide goals and purposes. Adaptive management activities constitute only some of the many tasks within RECOVER. The RECOVER teams are not decision-making bodies. They make recommendations to the Corps and to the South Florida Water Management District, the latter which both implements and manages the project. The regulations indicate that these organizations are to use reports from RECOVER, reports of an independent scientific review panel (to be convened by the National Research Council), or other appropriate information for improving the plan by modifying its operations, goals, physical components, or the sequence of their implementation. An Initial Restoration Plan update (ICU) is planned, in which the plan is to be reconsidered and redefined.

The General Accounting Office (2003) reviewed interagency science coordination related to the restoration of the South Florida ecosystem. From 1993 through 2002, federal and state agencies spent $576 million to conduct mission-related scientific research, monitoring, and assessment. However, the GAO found that the “key tools needed for effective adaptive management have not yet been developed, including (1) a comprehensive monitoring plan for key indicators of ecosystem health and (2) mathematical models that would allow scientists to simulate aspects of the ecosystem and better understand how the ecosystem responds to restoration actions” (GAO, 2003). It was further noted that: “without such tools, the process of adaptive management will be hindered by the fact that scientists and managers will be less able to monitor key indicators of restoration and evaluate the effects created by particular restoration actions” (ibid.).

Even more recently, adaptive monitoring and assessment within the Comprehensive Restoration Plan was reviewed by the National Research Council Committee on Restoration of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem (CROGEE). The report from that committee concluded that: (1) the monitoring needs must be better prioritized; (2) system-wide indicators of ecosystem status should be developed to add to the present more nar-

rowly defined indicators; (3) region-wide assessment of external human and environmental drivers (such as population growth, land-use changes, water demand and sea level rise) is needed; (4) monitoring, modeling and research should be integrated to promote learning within an adaptive management framework; and (5) the process for scientific feedback to the restoration plan needs more consideration (NRC, 2003a). A 2003 draft monitoring and assessment plan from RECOVER (http://www.evergladesplan.org/pm/recover/aat.cfm; accessed January 28, 2004) represents some progress in addressing these concerns.

Summary

Adaptive management in the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan is currently more of a concept rather than a fully-executed management strategy. As outlined in the programmatic regulations governing the implementation of CERP, adaptive management is broadly defined. It is being applied to all aspects of performance, including progress toward achieving non-environmental outputs such as domestic water supply and maintenance of flood protection. The plan’s ultimate restoration objectives are broadly and generally defined. To date, specific interim performance measures have not been developed, nor is it clear how the RECOVER teams will establish appropriate interim performance measures. The focus of the adaptive management effort is to relate outcomes and plan activities. There is, however, little explicit consideration of factors outside the plan (the external human and environmental drivers identified by CROGEE; NRC, 2003) that may influence ecological or other outcomes and that such factors must be considered within adaptive management. Some of these factors, such as prospective future changes in precipitation patterns, the direction and magnitude of which are not clearly understood, may be beyond the ability of managers to immediately prepare for. But other, more immediate factors such as population growth and associated increased water demands, are currently influencing outcomes and may be amenable to ameliorative actions.

An adaptive management approach in the Comprehensive Restoration Plan is an ambitious undertaking. Substantial investments in scientific activities have been made. However, reviews by the General Accounting Office and the National Research Council Committee on Restoration of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem emphasized that significant improvements in the monitoring program, including priority setting and development of more comprehensive indicators of outcomes, are still

required. This is essential because monitoring and ongoing assessment plays a central role not only in measuring outcomes, but also in refining attainable goals and modifying plans to achieve them. A review of the plan illustrates the remaining challenges in fully integrating modeling, monitoring, and research into a framework that emphasizes learning for refining models, and in developing institutional mechanisms to ensure that knowledge gained is effectively applied in adaptive management. The Comprehensive Restoration Plan is on the leading edge of the Corps’ efforts to apply adaptive management in ecosystem restoration. These early evaluations of progress and shortcomings not only provide the opportunity for mid-course correction, but also serve as important lessons learned for adaptive ecosystem restoration in other parts of the nation.

MISSOURI RIVER DAM AND RESERVOIR SYSTEM

The Pick-Sloan Plan

The most important and lasting water development project on the Missouri River was the Pick-Sloan Plan. Passed as part of the 1944 Flood Control Act, the Pick-Sloan Plan represented a merger of plans prepared by the Corps and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The Corps’ plans focused on navigation enhancement and flood control through several dams on the Missouri’s mainstem. The Corps’ plans were being coordinated and promoted by the Corps’ Missouri River Division Engineer, Colonel Lewis Pick. The Bureau’s plans focused on irrigation and hydropower, and were developed in large part by the Bureau’s regional director, Glenn Sloan. The Bureau’s plans called for some ninety dams and reservoirs across the basin, along with hundreds of irrigation projects that would have doubled the basin’s irrigated acreage (Carrels, 1999). Both plans were presented to Congress at a time when the creation of a basin-wide Missouri River authority was being considered. The proposal to create a basin-wide authority was decidedly unpopular with both the Corps and the Bureau, but there was pressure from President Franklin Roosevelt to create a single plan for basin development. To forestall the creation of a new basin-wide authority, Pick and Sloan and their respective agencies agreed to combine their plans. Congress approved the combined plan, directing the Corps to build the mainstem dams and the Bureau to provide water to irrigated agriculture. Prior to the passage of

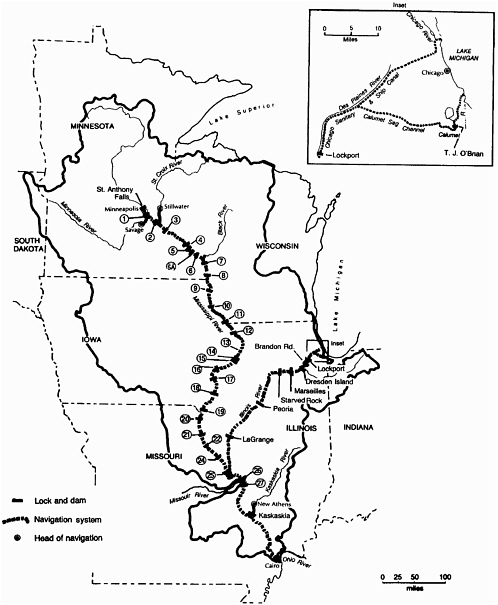

the Pick-Sloan legislation, the Corps constructed one large dam on the Missouri River—Fort Peck Dam in Montana—which was built in the 1930s. Under Pick-Sloan, the Corps built five additional mainstem dams in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to these six mainstem dams, the Bureau of Reclamation built Canyon Ferry Dam (also in Montana). There are today seven dams and reservoirs along the Missouri River (see Figure 4.2 , in which the three largest reservoirs are labeled).

FIGURE 4.2 Missouri River Basin. SOURCE: Modified from NRC (2003).

Current Setting

The Missouri River dam and reservoir system supports a variety of uses, including recreation, fisheries, hydroelectric power generation, and flood control. The river also supports commercial navigation on a 735-mile stretch from the river’s mouth at St. Louis upstream to Sioux City, Iowa. Water releases from the system’s most downstream dam—Gavins Point—are scheduled to support a 9-foot navigation channel. Navigation is among the most controversial issues in current discussions of system operations. It was expected that the mainstem dams constructed as part of Pick-Sloan were going to generate substantial navigation benefits. But commercial traffic levels on the Missouri River have fallen well short of 1950 projections, peaking in 1977 at 3.3 million tons, with a fairly steady decline since then, to near 1.6 million tons in 1997 (USACE, 2000b). In comparison, barges on the Upper Mississippi carry more than 80 million tons per year (USACE, 2000b). Commercial navigation generated a modest (when compared with other benefits) level of $7 million of benefits in 1995 (USACE, 1998). Most of those navigation benefits are concentrated in the downstream sections of the navigable channel. The Corps maintains this 9-foot navigation channel pursuant to the 1945 Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project. Since passage of this legislation, recreational use of the mainstem lakes has become much more important to upper basin economies. According to Corps data, recreation on the mainstem lakes increased from less than 5 million visitor hours in 1954 to more than 60 million visitor hours in fiscal year 2000 (USACE, 2000a). Annual recreational benefits for the region are estimated by the Corps at over $80 million annually (USACE, 1994).

Authorized purposes of the dams and reservoirs include flood damage reduction, water supply and irrigation, navigation, hydropower, fish and wildlife, and recreation. Some of the values of these authorized purposes have changed greatly since the Pick-Sloan era. The appropriate balance of these sometimes competing uses are central to the current decision making context for the Missouri River dams and reservoirs, and figure prominently in the Corps’ ability to implement an adaptive management framework for the river and its basin. Management protocols for the Missouri River include many federal laws, one of which is the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973. There have been significant post-settlement changes to riverine ecology: of 67 native fish species on the mainstem river, 51 are currently listed as rare, uncommon, or de-

creasing (NRC, 2002). One fish species (the pallid sturgeon) and two bird species (the least tern and the piping plover) are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. In addition to these legal responsibilities, many stakeholder groups representing a wide and sometimes conflicting variety of preferences and values are intensely interested in management of the river. Interest groups that compete for Missouri River benefits include the basin states, navigation interests, environmental groups, floodplain farmers, river communities, and Native American tribes.

The Corps Master Manual

The six mainstem dams and reservoirs that the Corps operates on the Missouri River comprise the core of North America’s largest reservoir storage system. The operations guidelines for this system are embodied in the Corps’ Missouri River Master Water Control Manual, or “Master Manual,” the first version of which was issued in 1960 by the Corps’ Omaha office, which codified operations practices developed over the previous decades (Ferrell, 1996). The Master Manual does not define specific operating priorities for the system, but it does provide general guidance for addressing possible conflicts between uses. The Master Manual is supplemented by a more detailed Annual Operating Plan (AOP), which is also prepared by the Corps. In response to drought conditions across the Missouri River basin in the late 1980s, and because of strong differences of opinion on how the reservoirs should be operated, the Corps began revising the Master Manual. To date, the Corps has not yet produced a revised version of the Master Manual, a situation that reflects the complex and contentious political and legislative setting along the Missouri River.

Implementing Adaptive Management

The Corps has been involved with habitat restoration efforts on the Missouri since the mid-1970s. In cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and with state conservation agencies, the Corps has implemented projects to mitigate the loss of natural resources resulting from bank stabilization and channelization of the river system. Formal authorization of the mitigation program dates to the 1986 Water Resources Development Act. The stated goal of the mitigation project was to restore five to ten percent of the habitat lost from the bank stabiliza-

tion and navigation project (Ferrell, 1996; USGS, 1997). Mitigation continues through experimental modifications of river structures, such as dikes, and enhancement of river flow through side channels and into backwater areas. Under the 1986 authorization, mitigation has been completed at nine sites, is underway at nine others, and nine additional sites have been targeted for acquisition (NRC, 2002). The emphasis in this mitigation project has been on terrestrial habitat, not on restoring pre-settlement ecosystem processes such as overbank flooding and cut-and-fill alleviation (see NRC, 2002, for more detailed advice on implementing adaptive management within Missouri River dam and reservoir system operations).

More substantial efforts at restoration that would adjust river flows to more closely mimic pre-settlement hydrologic patterns, however, have not received acceptance among all stakeholders, particularly among agricultural and navigation interests. In its Final Missouri River Biological Opinion issued in late 2000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) recommended an adaptive management program for managing river flows. The Fish and Wildlife Service recommended altering the current and steady year-round flows (approximately 32,000 cubic feet per second) to allow for more seasonal flows, a proposal that sparked intense debate, from hearings along the river to testimony presented to the U.S. Congress. Communities and some interest groups along the lower river, and elected officials from the State of Missouri, are concerned about potential impacts of high spring flows on agriculture and of low summer flows on navigation traffic. In contrast, upper basin state interests and their political leaders call for changes in order to avoid lowering upstream reservoirs in the summer that would harm the recreation industry there. Environmental groups call for restoration of some degree of seasonal flows that are fundamental to habitat restoration and to protecting endangered species.

The Corps released a draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for revision of its Master Manual in August 2001. In that document, the Corps explained potentially useful efforts to move toward adaptive management of the Missouri River dam and reservoir system. Successful implementation of the concept, however, is constrained by the conflicts embodied within an array of federal laws, congressional authorizations, administration guidance, the Corps’ own internal guidance, and differences of stakeholder opinion. Faced by the inconsistencies within this body of water policy, the Corps has been reluctant to depart from traditional authorizations (namely the 1945 Missouri River Bank Stabilization

and Navigation Project that authorizes a nine foot navigation channel), even when it has the legal authority to do so. As a result, the status quo remains in place and the impasse between conflicting objectives must be broken by Congress or by the courts.

The Corps has embraced the spirit of adaptive management in some of its recent Missouri River system planning documents. Conflicts and inconsistencies among statutory responsibilities, court orders, agency opinions, and stakeholder preferences continue to confound adaptive management actions on the Missouri River mainstem. A series of events as this report went to press illustrate these legal, political, and social entanglements. In July 2003, a federal district court ordered the Corps to temporarily lower Missouri River flows from mid-July to early September in order to comply with the Endangered Species Act. The flow reductions ordered were consistent with flow targets issued in a 2000 Biological Opinion from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—from 25,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) at Gavins Point Dam to no more than 21,000 cfs until August 15, and to not more than 25,000 from August 15 to September 1. These flow reductions were relatively moderate in both duration and scale and posed relatively low risks for users along river (e.g., power plant cooling stations; drinking water supplies). They also offered an opportunity to examine ecosystem responses to changes in flow. Yet rather than reducing flows from Gavins Point Dam, the Corps opted to contest the court order. The Corps argued that the order was inconsistent with an earlier injunction issued by a different federal district court that ordered the Corps to operate the river in accordance with its Master Manual. The court found, however, that the Corps' refusal to lower the river as ordered was inconsistent with their obligations pursuant to the Endangered Species Act, and held that the Corps was in contempt of court. The Corps ultimately lowered flows consistent with the FWS flow targets—for three days at the end of the flow period suggested by the FWS. In December 2003, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued another Biological Opinion that maintained the Corps would violate the Endangered Species Act if the agency refused to lower summer water flows to benefit the endangered pallid sturgeon, and that a “spring rise” was not required because the Corps dam operations are not jeopardizing the least tern and the piping plover. Whatever the correct explanation for the events during the Summer of 2003, they at least forestalled an opportunity to apply adaptive management actions to managing the Missouri River Dam and Reservoir System and to restore some degree of pre-settlement processes.

Summary

Missouri River management is legally complex and highly politically charged, and efforts to adjust status quo operations are strongly contested. In this instance, reasons for the Corps' reluctance to lower river levels to uphold its obligations pursuant to the ESA might include a lack of support from the administration and the Congress to make such changes, political influence of influential constituents, or an inertia that favors traditional authorities over more contemporary statutes. Although detailed investigation of these issues was beyond the scope of this study, a previous National Research Council report considered these issues in some detail, and concluded that clarification from the U.S. Congress regarding Missouri River objectives was essential to better management: “Support of the U.S. Congress is ultimately needed to help establish goals for the use and management of the Missouri River system. Congress must also identify the necessary authorities to do so” (NRC, 2002).

The Corps has embraced the spirit of adaptive management in some of its recent guidance (e.g., its 2001 revised draft environmental impact statement; USACE, 2001b) for Missouri River management. Some elements of adaptive management do exist in the basin. For example, the Missouri River Basin Association (MRBA) has recently convened workshops that engaged basin stakeholders to discuss prospects for adaptive management, ecosystem monitoring, and more effective stakeholder participation on Missouri River management issues. The MRBA, which is a coalition of governor-appointed representatives from each of eight Missouri River Basin states (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming) and the Executive Director of the Mni Sose Tribal Water Rights Coalition, has also been considering adaptive management efforts in other U.S. river systems, such as the Colorado River and the Upper Mississippi River, and how they might inform adaptive management for the Missouri. The U.S. Geological Survey sponsors the Columbia (MO) Environmental Research Center, which conducts research on large river floodplains and the effects of habitat alterations on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. State fish and wildlife agencies across the basin have also formed the Missouri River Natural Resources Committee, which aims to promote environmental stewardship based on ecological principles. A Missouri River Roundtable, with federal agencies as members, has also been created. Despite these and other positive developments across the basin, the Corps remains frustrated in its efforts to revise its Master Manual. As events in

the Summer of 2003 demonstrated, water management tensions in the Missouri are often resolved in courts. Support from the administration and Congress will be essential to creating an integrated and coherent adaptive management program for Missouri River management.

UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER

The Navigation System

The Upper Mississippi River begins at Lake Itasca, Minnesota, and ends at Cairo, Illinois, at the confluence of the Mississippi and the Ohio rivers (Figure 4.3). The Upper Mississippi River—Illinois Waterway (UMR-IWW) system also includes the Illinois River, which flows from near Chicago downstream to its confluence with the Mississippi at Grafton, Illinois. In the 1930 Rivers and Harbors Act, Congress authorized a 9-foot channel navigation project for the Upper Mississippi River. Pursuant to that act, the Corps constructed a series of locks and dams on the river. The dams created navigation pools that provided sufficient depth to support a 9-foot channel. There are today 29 locks and dams on the Upper Mississippi River, most of them constructed in the 1930s, and the Corps still maintains a 9-foot navigation channel. Commercial barge traffic carries grain (downstream), coal (upstream and downstream), and fertilizer and petroleum (upstream; NRC, 2001b), and several other products including scrap metal, sand and gravel, and vegetable products. The Upper Mississippi River supports many other uses, including the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge (the longest such refuge in the United States), which supports a vibrant hunting, sport fishing, and boating enterprise.

Ecosystem Monitoring and Science

The Upper Mississippi River Environmental Management Program (EMP) was established as part of the Water Resources Development Act of 1986. The EMP originally had three components: 1) habitat rehabilitation and enhancement projects (HREPs), 2) Long Term Resource Monitoring Program (LTRMP), and 3) Computerized Inventory and Analysis (USACE, 1997). The Corps has overall management responsibility for the EMP. The LTRMP is today overseen by the U.S. Geologi-

cal Survey, in cooperation with the five Upper Mississippi River System states (Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin). In 1999 the LTRMP became part of the Upper Midwest Environmental Science Center (UMESC) in La Crosse, Wisconsin. In a review of the EMP, the Corps stated that “ … the EMP has come to be the single most important and successful program authorized by the Federal government for the purposes of understanding the ecology of the UMRS and sustaining its significant fish and other resources” (ibid.).

The LTRMP’s primary mission is to analyze and report upon ecological conditions and trends of the Upper Mississippi River. The UMESC gathers ecological data through field, laboratory, and remote sensing methods, and the center has published hundreds of scientific and technical documents. In 1999 the UMESC issued a report that reviewed the ecological status and trends of the entire Upper Mississippi River system (USGS, 1999). The report represented a landmark of sorts, as it was the first time that the LTRMP data and historical observations were summarized in a single report. The report found that “Historical observations and research findings together make it clear that the reaches have been changed by human activity in ways that diminished their ecological health,” but also concluded that “the ecological potential of the UMRS remains great” (USGS, 1999).

Although there is no congressional mandate to manage the Upper Mississippi River according to adaptive management principles, the Corps has been varying the heights of some Upper Mississippi’s navigation pools in an effort to reintroduce a degree of natural variability to the ecosystem and thereby improve ecological conditions. The Corps began these efforts with several small-scale (on the order of a few inches of pool drawdown) efforts in 1996-1999. Drawdowns were conducted in Pool 8 (formed by Lock and Dam Number 8 at Genoa, Wisconsin) during 2000 and 2001. The fluctuations were relatively modest: in 2000, pool height was initially dropped six inches at the upper end, and in 2001 the height was dropped three inches. Some adaptive management elements were embodied in these actions, including citizen involvement (in establishing the magnitude of the drawdowns) and monitoring of the results of management actions. A review of these actions could yield insights into the responses of both ecosystems and human uses, and may thus hold lessons in the Corps’ abilities and constraints in implementing adaptive management.

Outcomes

As one of the nation’s large environmental monitoring programs that includes the Corps, it is important to ask how resources devoted to the EMP and LTRMP have proven informative and useful. Since the EMP’s establishment in 1986, the most important management issue on the Upper Mississippi River has been the prospect of extending several locks (just north of St. Louis) in an effort to relieve occasional waterway traffic congestion. Formal investigations by the Corps into the economic justification for these extensions dates back to the late 1980s and continues today. Current plans call for a report with a final recommendation to be released in late 2004. During the course of the Corps’ feasibility study, the U.S. Department of Defense requested the National Research Council to form a committee to investigate the economics and related analyses within the ongoing study. That committee’s report stated:

Although there has been some systematic research into the environmental effects of human and social activities on the Upper Mississippi River [the EMP] , the understanding of the complex ecosystem dynamics in the UMR-IWW system is limited in many areas … characterization of the current environmental system is insufficient, as it is in the early stages of scientific validation. Systemwide research should be conducted on the following topics: (1) cumulative effects of the existing navigation system on river ecology, (2) environmental effects of recent navigation system improvements, (3) cumulative effects of increased towboat passage, and (4) site-specific effects of future construction activities (NRC, 2001b).

The NRC report also concluded, “The EMP research effort should be enhanced to improve the assessment of the current navigation system’s cumulative effects on the environment, and broadened to include studies of the impacts of barge traffic on river ecology.” Despite possible past constraints on the EMP (which this panel did not investigate), the 1999 U.S. Geological Survey’s “Status and Trends” report noted that sufficient data now have been collected so that the EMP could provide useful information for future river management decisions on the Upper Mississippi.

Summary

There is no federal legislation requiring adaptive management principles to be used in managing the Upper Mississippi River and its floodplain ecosystem. Nonetheless, some elements of an adaptive management program, such as the extensive ecosystem monitoring program managed by the Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, are in place (although the monitoring program is not specifically designed to support adaptive management). The Corps, working in cooperation with the U.S. Department of the Interior, is also striving to introduce adaptive management concepts to management of the Upper Mississippi River ecosystem, and a recent Corps draft report demonstrates a good understanding of key concepts and implementation challenges (Lubinski and Barko, 2003). To its credit, the Corps and some of its fellow federal agencies, and some state resources management agencies, took the initiative to implement experimental drawdowns of navigation pools. Those drawdowns were heavily constrained, however, and thus of a small magnitude.

One observation is that the Corps will be unable to implement adaptive management principles unilaterally; cooperation from federal and state agencies and stakeholders will be required, especially in large ecosystems like the Upper Mississippi. The Upper Mississippi experience is important because it shows that formal management actions with river systems can be framed with stakeholder input and can improve scientific knowledge. The Upper Mississippi also shows the importance of the physical and social settings in which adaptive management is implemented. The Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge contains large expanses of publicly-owned backwater and floodplain areas, which allows the Corps some latitude in varying river flows and surface elevations. The drawdowns were implemented in a region where many inhabitants view the Mississippi River as a valuable ecological resource that supports important economic and leisure activities. Moreover, the Corps communicated closely with stakeholders before and during these drawdowns and has used stakeholder preferences to limit the extent of the drawdowns. This has led stakeholders to develop a degree of trust in the Corps and to a realization that adaptive management-type experiments can entail only limited impacts on activities such as boating. This trust could be important if a larger drawdown(s) is proposed in the future.

A fuller understanding of these positive and innovative efforts must be framed in terms of other adaptive management principles and the

condition of the Upper Mississippi River ecosystem. It is important to note that adaptive management entails not only procedural components, such as monitoring and adaptation, but also substantive dimensions. For example, a traditional tenet of adaptive management is the promotion of ecosystem resilience. In the 1978 landmark volume on adaptive management, C.S. Holling stated:

The concept of resilience, in which the different distinct modes of behavior are maintained because of, rather than despite, variability, is suggested as an overall criterion for policy design. The more that variability in partially known systems is retained, the more likely it is that both the natural and management parts of the system will be responsive to the unexpected (Holling, 1978).

Resilience refers to an ecosystem’s ability to recover from disturbances and to be self-sustaining without human intervention (Gunderson, 2000). The benefits of resilience are difficult to identify and estimate, however, which poses challenges to its implementation for a constructions and operations-oriented agency like the Corps. On the Upper Mississippi River, ecological conditions and trends suggest that ecological resilience has been compromised by the lock and dam and navigation pool system and that most key indicators suggest that conditions are not improving. For example, the 1999 USGS report noted the following in regard to floodplain forests:

… the UMRS retains its ability to regenerate early successional forest communities only in the Unimpounded Reach, where water levels fluctuate. Forests in pooled reaches apparently are limited by water-level regulation for commercial navigation and show little ability to reset in response to disturbance. The navigation dams likely will limit the health and diversity of forests within the Impounded Reaches for the foreseeable future (USGS, 1999).

Despite the noted ecological importance of water level fluctuations, efforts at restoration along the Upper Mississippi have emphasized restoration of highly managed habitats, rather than the restoration of hydrologic and related geochemical and biological processes that contribute to ecological resilience.

The roles and influence of the administration and Congress on the

Upper Mississippi are of great importance. In the 1986 Water Resources Development Act (WRDA 1986), the Upper Mississippi River Management Act stated that the river was to be recognized as “a nationally significant ecosystem and a nationally significant commercial navigation system” (P.L. 99-662). Despite this stated importance of ecological well-being, maintenance of the nine-foot navigation channel remains the prevailing authorization on the Upper Mississippi River. As pointed out in the 1999 U.S. Geological Survey report, the navigation pools and reduced variability in Mississippi River flows and river levels have negatively impacted river ecology: “Historical observations and research findings together make it clear that the reaches have been changed by human activity in ways that diminished their ecological health” (USGS, 1999). The WRDA 1986 legislation does not provide clear guidance to the Corps on how to appropriately balance traditional economic values (navigation) and environmental values. Lacking clear direction on how to appropriately balance these values, the Corps abides by the congressional mandate to provide a minimum nine-foot channel, and implements environmental restoration and protection programs such that this channel depth is not compromised. Environmental groups are generally dissatisfied with this operational regime, claiming that the balance called for in the WRDA 1986 has “ … never been reflected in national policy … ” and that “ … some balance between these competing needs must be sought” (League, 2003). The 1930 channel authorization does not require strict and permanent maintenance of a 9-foot channel, however, and the exploration of alternative operational regimes would allow the Corps more flexibility to implement adaptive management actions and increase ecosystem resilience. At the same time, some stakeholder groups and some citizens have demonstrated a reluctance to allow the Corps to enact substantial navigation pool drawdowns. Adaptive management could provide a framework for stakeholders and the Corps and other federal agencies to explore the relations and trade-offs between Upper Mississippi River ecology, navigation, recreation, and other uses in a more systematic fashion.

COASTAL LOUISIANA

Multiple Corps Responsibilities

For over a century the Corps has played a large role in coastal Louisiana through its flood control and navigation mission relative to the

Lower Mississippi River. The establishment of a system of levees along the lower river in the 1930s to both prevent flooding of adjacent lands and to confine to the river to its channel and thus enhance navigation, was consistent with a mandate to protect citizens and infrastructure from flooding and to facilitate economic development. The impact of these measures in isolating the Mississippi River Deltaic Plain from the river, and thus its sustaining source of freshwater and sediments, were unappreciated at the time. In the aftermath of the historic 1927 flood, the Corps was also directed to regulate the river flow from the Mississippi and Red rivers down the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf of Mexico and to construct and manage spillways to alleviate the risk of overtopping of levees. In the later half of the twentieth century, the federal interest was expanded to include a number of relatively deep navigation channels, such as the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet and Calcasieu Ship Channel, connecting inland ports and waterways with the Gulf of Mexico. These channels caused salt water to intrude into previously freshwater bays, bayous, and wetlands. The network of flood protection levees was also extended to afford communities protection from storm surges and backwater flooding. The Corps regulatory programs also played a role in the dramatic environmental changes in coastal Louisiana, permitting extensive channelization of coastal wetlands mainly related to oil and gas exploration, development, and transportation.

Wetland Loss

As a result of the cumulative effects of these and other alterations of the coastal landscape, and the disruption of the processes that created and sustain the delta and adjacent coastal environments and natural processes, the marshes, swamps, bays and barrier islands that comprise coastal Louisiana experienced dramatic changes during the latter half of the twentieth century. The rate of net loss of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands has been estimated at 25 to 35 square miles per year during various segments of this half-century (Louisiana DNR, 1999), posing threats to the productivity and biological resources of the coastal ecosystems, the safety of residents, and the infrastructure supporting this population and important industries such as oil and gas production.

The causes of rapid wetland loss and change in the characteristics of associated estuarine environments are multiple and complexly interrelated. The changes accompanied and followed pervasive physical and

hydrological alteration of the estuarine-wetland complex itself at a number of scales. The large-scale navigation channels mentioned above facilitated more extensive and vigorous tidal exchange and interconnection of previously isolated hydrological basins. Extensive canals were dredged through the wetlands to afford access to oil and gas exploration and production sites and corridors for transportation of product via pipe-lines. In addition to the direct losses of wetland due to dredging, the material removed was typically side cast as spoil banks that interrupt the natural inundation and drainage of the wetlands. Still other wetlands were affected by impoundments associated with failed agricultural conversion or with water-level management to provide waterfowl habitat. The net direct and indirect consequences of these physical and hydrological alterations were greater intrusion of tides, storm surges, salinity, and impoundment of water on wetland surfaces that causes mortality or prevents recruitment of emergent plants.

The human-induced changes that began even earlier (i.e. closure of distributaries along the lower river such as Bayou Lafourche and the prevention of flood-induced crevasses and seasonal overbank flooding) led to a longer-term problem for the Deltaic Plain wetlands. The periodic supply of sediments, fresh water, and nutrients from the Mississippi River has historically built and sustained the wetlands in the face of very high rates of relative sea-level rise due to subsidence of the thick layer of Holocene sediments on which the wetlands sit. In addition, it now appears that withdrawals of oil, gas, and associated formation waters during the last half of the twentieth century caused accelerated subsidence in some regions of the coastal zone. The only portions of the Louisiana coastal zone that have had only minor losses of wetlands or that have actually gained wetlands are adjacent to the mouth of the Atchafalaya River, which receives thirty percent of the combined flow of the Mississippi-Red river system. These wetlands have received the fluvial subsidies that have been interrupted elsewhere. Scientific consensus suggests that whatever the cause, channelization of wetlands, subsidence, or even accelerated sea-level rise due to global warming, reconnection to the fluvial supply of sediments and other materials that build and sustain the coastal wetlands must be the foundation for maintaining and restoring coastal Louisiana’s ecosystems (Boesch et al., 1994).

Role of the Corps in Wetland Restoration

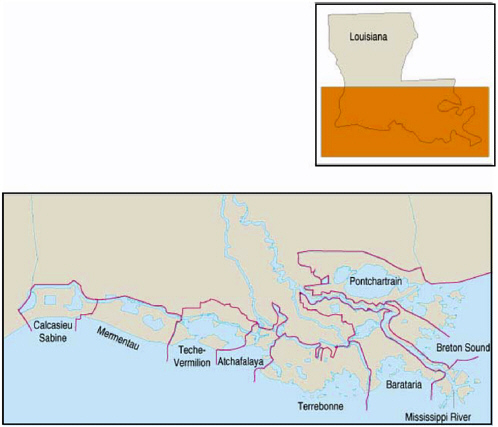

In recent decades, the Corps has been the lead agency in efforts to address some of the effects of these actions through projects justified on the basis of their net economic development benefits, rather than for ecosystem restoration. These include the placement of materials dredged from river channels to create or protect wetlands and controlled diversions of Mississippi River waters into adjacent estuaries and wetland at Caernarvon and Davis Pond, the former into the Breton Sound Basin and the latter into the Barataria Basin (Figure 4.4). The latter projects aim to restore salinity gradients to benefit economically important estuarine oyster habitat.

FIGURE 4.4 Louisiana Coastal Wetlands. SOURCE: Johnston, et al. (1995).

The role of the Corps of Engineers in the restoration of coastal Louisiana ecosystems expanded significantly with passage of the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act of 1990 (CWPPRA, PL-101-464). Although this act is national in scope, it established a priority for Louisiana wetland restoration projects. CWPPRA provides a dedicated federal revenue stream of approximately $35 million per year for restoration projects selected and managed by a federal-state Task Force (the Corps receives the appropriations and chairs the Task Force). To date, there have been 141 different CWPPRA projects across coastal Louisiana (USGS, 2003), most of which have been demonstrations or relatively small projects involving shoreline protection, hydrological restoration, or wetland creation.

The federal agencies represented on the CWPPRA Task Force and the State of Louisiana realized, however, that although the CWPPRA projects have been increasingly integrated within the hydrological basins along the coast, the approach was still piecemeal and inadequate in scale to significantly reduce, much less, reverse the rate of wetland loss across the state. The funding level for CWPPRA did not allow consideration of the large and expensive diversions of river water into the surrounding wetlands that experts thought would be needed to effectively address the problem. The Task Force and the state produced a much more comprehensive and ambitious strategy, Coast 2050: Toward a Sustainable Coastal Louisiana (Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Conservation and Restoration Task Force and the Wetlands Conservation and Restoration Authority, 1998; http://www.mvn.usace.army.mil/prj/lca/; accessed May 4, 2004), which included more than 80 projects and actions to achieve objectives for each of the hydrological basins along the coast.

The feasibility and benefits of many of the approaches included in the 2050 Plan are highly speculative. Consequently, the Corps of Engineers, with co-sponsorship by the State of Louisiana, is currently undertaking the Louisiana Comprehensive Coastwide Ecosystem Restoration Feasibility Study, or LCA Study for short. The LCA study builds on the 2050 Plan, but seeks to provide more rigorous analysis of design alternatives, benefits and costs within each of three subprovinces along the coast (Figure 4.4). Led by the New Orleans District office, the Corps is preparing a report to Congress that will seek authorization under the Water Resources Development Act for a comprehensive program to address wetland loss in coastal Louisiana. The authority would be for an umbrella program, much like the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Project, under which specific projects would be subsequently authorized and funded.

Summary

Various forms of adaptive management have been employed in several previous projects implemented by the Corps for economic development, for CWPPRA projects, and in the development of the Louisiana Comprehensive Coastwide Ecosystem Restoration report. River diversions at Caernarvon and Davis Pond have been monitored to determine the effects on salinity distribution and to address concerns about the introduction of harmful substances or other undesirable effects. Although not specifically designed to support adaptive management, interpretations of the monitoring data at Caernarvon (Lane et al., 1999) have contributed to quantifying nutrient removal and wetland growth rates in ways useful to the design of future diversions and the operational regimen for this diversion. For example, analysis of results from the estuaries and wetlands receiving the Caenarvon diversion have led to the realization that significant restoration benefits could be achieved through pulsed releases lasting several weeks while avoiding undesired salinity lowering on oyster grounds lower in the estuary. This is now being tested by more closely monitoring experimental releases within an adaptive management framework.

The LCA Study is explicitly applying adaptive management, within the Corps’ existing authorities, as a means of refining the design and operation of specific projects and learning by doing within the envisioned umbrella program that will extend over several decades. An adaptive management approach is particularly suited to the emerging strategy because of the multiple, but similar, water diversion and control components that are being considered, and because of the uncertainties involved not only in project performance, but in other important variables (e.g., variations in river flow, impacts of hurricanes, etc.).

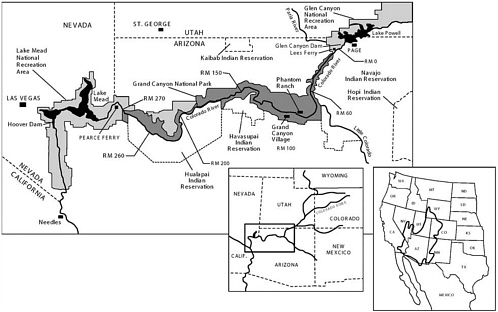

GLEN CANYON DAM AND THE COLORADO RIVER ECOSYSTEM

One of the notable and sustained adaptive management efforts in the United States is the Glen Canyon Adaptive Management Program (AMP). Founded in 1995 to help meet the monitoring requirements established in the 1992 Grand Canyon Protection Act, the AMP is building upon the extensive scientific program of the former Glen Canyon Environmental Studies (or GCES, which was conducted in two phases, 1982-

1988 and 1988-1996). The Adaptive Management Program is focused on the Colorado River ecosystem in the Grand Canyon (Figure 4.5). The Secretary of the Interior’s designee administers the AMP. The Grand Canyon Protection Act of 1992 mandates operation of the dam to “… protect, mitigate adverse impacts to, and improve the values for which Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were established.” An Environmental Impact Statement (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 1995), conducted in response to concerns over the downstream effects of the operations of Glen Canyon Dam, established the AMP to provide advice to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior on a continuing basis.

An Adaptive Management Work Group (AMWG) includes representatives of roughly two dozen groups with interests in the Grand Canyon and in Glen Canyon Dam operations (these groups include federal and state agencies, environmental groups, Indian tribes, and power and recreation interests). A Technical Work Group (TWG), composed mainly of representatives of the AMWG stakeholders, advises the AMWG on scientific and technical matters. The program also features a science center, composed of full-time staff, known as the Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center (GCMRC) in Flagstaff, AZ. The center is responsible for monitoring Colorado River ecology to help improve understanding of the downstream effects of Glen Canyon Dam operations. And, according to the 1995 environmental impact statement that described the structure and operations of the AMP, it is also to include an independent review panel(s) (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 1995). Although the Corps of Engineers is not a participant in the Adaptive Management Program, the preeminence and lengthy experience with adaptive management in the Grand Canyon should be of interest and value to the Corps.

The AMP is based on recognition that operations of Glen Canyon Dam have significantly altered downstream ecology of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Section 1802 (a) of the AMP has implemented some adaptive management program components to good effect. The Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center has taken the lead in informing stakeholders about the goals of and uncertainty involved with adaptive management. Through activities ranging from meetings to rafting trips, stakeholders have developed informal relations and lines of

communication. Experimental flows have been conducted, the most notable being a controlled flood in March 1996 when high water flows were released from the dam to simulate the spring rise that, in pre-dam conditions, transported sediment and helped restore beach habitat. Another experiment in the summer of 2000 involved low water flows in an effort to enhance conditions for native fish species. These experiments were extensively monitored and the results used in subsequent deliberations about dam operations.

The AMP is, however, struggling with the constraints inherent to most adaptive management efforts. Different values and priorities among stakeholders have stymied the creation of a set of clearly stated management objectives. As noted in a 1999 National Research Council report, the AMP has “not produced a scientific and stakeholder-based consensus regarding the desired state of the ecosystem.” Further, the range of possible experimental actions is limited by political and economic conditions. For instance, some recommended experiments in 2001 were postponed because of increased energy demand on the West Coast. Finally, and importantly, the independent review component of the program has never been fully and formally implemented. Lessons from the Adaptive Management Program that may be useful for the Corps include: the value of a congressional act in keeping focused on ecosystem recovery, the difficulties in forging consensus among stakeholders, the uncertainties and disagreements associated with some ecosystem monitoring results, the limitations of science to help establish management actions, and the potential value of (as well as some resistance to) independent review in addressing controversial or sophisticated issues.

COMMENTARY

The Corps has implemented some adaptive management principles and programs, with degrees of support from the U.S. Congress ranging from no specifically authorized capacity, to resources for monitoring and science programs, all the way to explicit authorization of adaptive management in the Florida Everglades. A review of the case studies presented in this chapter yields several observations and some commonalities.

Adaptive management is often implemented in river and aquatic ecosystems that are experiencing ecological decline, sharp differences of opinion among stakeholder groups, and an inability to make significant

departures from the status quo. Many parties, however, view the concept with skepticism; defenders of the status quo naturally resist new management directions, managers may interpret its implementation as indicating failure of their past decisions, some may view it as a vehicle to help circumvent environmental and other standards or for taking only minimal actions, and budgeteers may be concerned that it implies a blank check for an endless stream of monitoring and science-based programs. Whatever perspectives are held, successful implementation of adaptive management will require sustained participation. In addition to these barriers, actions taken under an adaptive management framework may not yield an abundance of positive and clearly understood results.

Paradoxically, however, these conditions may actually enhance the chances of the usefulness and success of adaptive management. Legislators should recognize that declining ecological conditions must eventually be addressed in order to conform with environmental statutes such as the Endangered Species Act. Stakeholders who wish to see management changes may welcome the prospects presented by adaptive management. In any event, the settings of declining environmental quality and political gridlock have often resulted from conflicts that have obstructed efforts to employ adaptive management-like principles and to adjust to emerging realities of shifting and broadening social preferences.

Decisive management actions and ecological recovery have, for the most part, not been realized, but given that it has often taken decades to arrive at the current situation, the way forward will require patience (whether adaptive management is used or not). Increased social preferences and attendant legislation aimed toward restoration of some degree of natural ecological processes and sustainability offer opportunities for adaptive management actions. Initiating communications among stakeholders is of great importance to the Corps and to the adaptive management process. The backing of the administration and the Congress, in terms of resources, as well as legislative authority, is crucial in encouraging sustained stakeholder participation in such efforts. In the Missouri, Congress has not established a formal adaptive management stakeholder group or larger program, or a formal basin-wide science program. By contrast, support from the administration and the Congress has been instrumental to the significant adaptive management programs in the Everglades and the Grand Canyon. Federal resources have been important to improving knowledge of ecological conditions in the Everglades, the Grand Canyon, the Louisiana Coastal Area, and within the Upper Mississippi River’s Environmental Management Program. Sustained support

from Congress for monitoring on the Upper Mississippi has helped synthesize and improve scientific knowledge of the Upper Mississippi River system. Congressional legislation mandating the Everglades restoration effort, establishing the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act, and creating a Grand Canyon Protection Act have legitimated efforts toward improving ecological conditions. Beyond the provision of resources, the administration and the Congress should help provide clearer direction to the Corps when the agency is obliged to respect legislation and administration guidance that reflects internal inconsistencies.