Strategies for U.S. Economic Growth

RALPH LANDAU AND NATHAN ROSENBERG

WITH THE MARKED SLOWING DOWN of U.S. economic growth and the apparent decrease in ability to compete in an increasingly international marketplace, more urgent attention from many quarters is now being directed toward finding the causes and cures. In this paper, we review what is known about the impact of technological change on economic growth. We emphasize that technological innovation has been the historic engine of U.S. economic growth, and we argue that it is equally critical to future growth and competitiveness. We find also that high capital investment rates are directly related to high productivity growth, which in turn is the key to rising prosperity and preservation of a high-wage economy. We conclude further that technological innovation and capital investment are essentially two sides of the same coin, and that the one without the other will not contribute significantly to the nation’s productivity growth. We analyze whether present U.S. economic policies, public and private, encourage or retard innovation and capital formation, and find that, in fact, they do not provide the stable, constructive environment required in these essential areas. Therefore, we propose improved strategies to preserve U.S. competitiveness and secure the social benefits of continued economic growth. We stress that competitiveness is not an end in itself but a means to increase such growth.

The growth rate in real income per person in the United States has been almost 2 percent per year since the Civil War. With this growth rate, standards of living nearly doubled between generations. Despite a simultaneous huge increase in population in this period, the United States moved from a largely rural economy to the greatest industrial power. Thus, the country’s average real growth rate in gross national product (GNP) was about 3 percent per year; from 1948 until recently it attained 3.5 percent. The United States surpassed the United Kingdom, at one time the leading industrial power,

which grew at a per capita increase of only 1 percent per year, and is now one of the poorer members of the European Common Market. On the other hand, Japan has surpassed even the high American growth rate in the period since the Meiji Restoration, which began in 1868. With a GNP growth rate of more than 5 percent since 1930, Japan has become the second-largest economy in the world.

Such is the power of compounding over long periods of time. Differences of a few tenths of a percentage point, which may not appear very significant in the short term, are an enormous economic and social achievement when viewed in the long term. Thus, it is of concern that the U.S. real GNP growth rate recently dropped to about 2.5 percent at the height of a long 5-year economic recovery. The basic question facing the United States today is whether it will be like the United Kingdom, while Japan and the Far East eventually outdistance it, or whether it will maintain a more prominent position of economic, and hence strategic, leadership.

QUANTIFYING THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE IN ECONOMIC GROWTH

It is obvious that the United States could have achieved its growth in per capita income in either of two very different ways: (1) by using more resources or (2) by getting more output from each unit of resources. How much of the long-term rise in per capita incomes is attributable to each?

For many decades economists approached this issue of rising per capita incomes as if it were primarily a matter of using more resources, especially capital equipment, all essentially unchanged. The first serious attempts at providing quantitative estimates came during the 1950s, and the answers came as a big surprise to the economics profession.

When, in the mid-1950s, Moses Abramovitz (1956) and Robert Solow (1956, 1957), among others, looked at the quadrupling of U.S. per capita incomes between 1869 and 1953 and asked how much of the observed growth could be attributed to the use of more inputs, the answer was about 15 percent. The residual—the portion of the growth in output per capita which could not be explained by the use of more inputs—was no less than 85 percent. What seemed to emerge forcefully from these exercises was that long-term economic growth had been overwhelmingly a matter of using resources more efficiently rather than simply using more and more resources.

Abramovitz was himself very circumspect in interpreting his findings, calling it “a measure of our ignorance.” Others attached the label “technological change” to that entire residual portion of the growth in output which cannot be attributed to the measured growth in inputs, and thus equated it to the growth in productivity. Productivity in this sense (multifactor) measures the efficiency of the inputs of both capital and labor, although the

figures on productivity most frequently cited refer to labor productivity, and economists generally employ the term in this way. Strict economic interpretation of this residual is not entirely satisfactory, however. Many social, educational, and organizational factors and considerations of scale and resource allocation are also at work. Nonetheless, if the definition of the role of technological change is viewed broadly enough, it is probable that it is indeed the central component of productivity growth.

This awakened interest in the 1950s by academic economists in the causes of long-term growth led to other studies by economists like Edward Denison (1985) of the Brookings Institution and John Kendrick (1984) of George Washington University in the 1960s and 1970s who applied different techniques and obtained varying results from refining the component causes of such growth.

THE REALIZATION OF THE MAJOR ROLE OF CAPITAL INVESTMENT

Long-term real productivity growth rates conceal considerable erratic variation in the short run. This extreme variability is caused by extraneous shocks, such as the oil price rises, cyclical variations of the economy, wars, inflation, and many others. Nevertheless, since 1966 productivity increases have greatly diminished from previous levels. For the period 1960–1979, the multifactor productivity growth of the U.S. economy was only 0.26 percent per year, and in much of the later part of this period, the growth of total GNP was brought about almost entirely by increases in capital and labor, especially (in the 1970s) the latter as the number of baby boomers entering the work force peaked. Although the explanations for the collapse in American productivity have varied, it seems clear from extensive recent studies by Harvard’s Dale Jorgenson and coworkers (1986, 1987) that the comparative performance of the U.S. and Japanese productivity growth rates (which in the same 1960–1979 period was 1.12 percent per year) has been heavily influenced by the much higher rate of Japanese capital investment. This high rate was well suited to a rapid adoption of the latest available technologies bought from many companies around the world, often at bargain prices. The Japanese investment was twice as high as the rate in many U.S. industries, which in some cases (e.g., steel) were not adopting technology with the same urgency. Other international evidence also suggests a high correlation between national investment and economic growth rates; for example, the Federal Republic of Germany and France, with investment rates roughly twice those of the United States, had about twice the productivity growth rate. Jorgenson’s research suggests that in the postwar era, capital formation has accounted for about 40 percent of economic growth, with productivity growth being 30 percent and increase in labor also being about 30 percent.

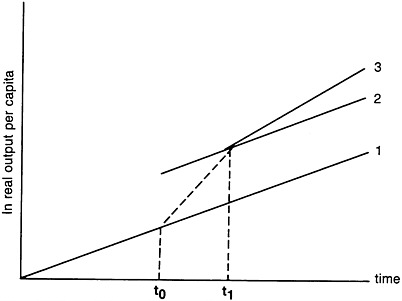

FIGURE 1 Alternative growth paths—technical change and capital formation. t0, Proinvestment policy leads to higher capital formation and transition to higher level of income. t1, Economy resumes long-term growth rate, or through interaction of investment and technical change, moves to more rapid growth path. SOURCE: Boskin (1986, p. 37).

Assar Lindbeck (1983) at the World Bank and Jorgenson et al. (1987) have each made recent extensive studies of the possible reasons for the productivity slowdown among various nations, and both draw particular attention not only to the lower rate of capital accumulation but also to the need to reallocate resources, because of the rise in energy costs or because of new regulations for greater environmental and health protection, etc. That the latter has had a detrimental effect on American international competitiveness, even though conferring genuine domestic benefits, is shown in a careful economic study by Joseph Kalt (1985) of Harvard University.

HOW GROWTH RATES CAN BE INCREASED

A complication in understanding the causes of growth is that quantitative measures of productivity do not fully describe the performance of any economy. Quality is difficult to measure, and of course, many goods and services have greatly improved in performance and variety and many new products have appeared, whereas the quality of other services may have deteriorated.

Nevertheless, significant insight into the key relationships is suggested by Figure 1. According to Michael Boskin (1986) of Stanford University, the fundamental variables that increase the rate of growth of a country in the long term are the rate of technical change (involving not only research and development [R&D] but also design, invention, market development, and the like) and the improvement in quality of the labor force. Merely increasing the rate of capital formation will lead to only a temporary increase in the

rate of growth (moving from growth path 1 to growth path 2). This increase in capital formation occurred during the 1960–1979 period in Japan, although it has more recently declined. These difficult-to-sustain large growth rates, which occurred as international resistance to the export-led drive increased, have now diminished, but permanent advantages for many industries have been created.

Measurements of productivity growth alone are not, however, a complete free-standing expression of the role of technology in economic growth. R&D by itself is seldom performed unless it is expected to be employed in new or improved facilities and in superior operating modes. Technological change is thus heavily carried by capital investment, but it is also a powerful inducement to it, since the availability of superior technology is a major incentive to invest. Likewise, improvements in labor quality (human knowledge, skill, and training) are both a carrier of and a spur to technological change. Hence, within each of the basic factors of production, technology often takes an embodied form. When more business capital is invested, new technology is usually embodied in it—it is seldom just a pure copy of what went before. Thus, the capital stock of a country is of different vintages, reflecting such changes.

Boskin’s growth path 3 in Figure 1 illustrates the point that if these interactions are in fact occurring, then the rate of investment can move the economy to a longer-term higher growth rate, as opposed to a mere upward shift in the level at any given time. This is especially true for the results of “breakthrough” R&D, which require large new investments. A substantial proportion of R&D is devoted to improving the performance of capital in place, or for ready modification or retrofitting by incremental investments, which require less new capital. Often even maintenance capital may embody improved technology, although the constraints imposed by the total process and product eventually force decisions for complete new plants using later technology if the firm is to remain competitive. Hence, in view of the really novel technologies now becoming available and the effects of continuing R&D efforts, the need for totally new facilities and closing down of obsolete units is becoming much greater if the United States is to remain competitive and to catch up with the Japanese spurt of the last 20 years. Some plants and even companies will disappear in the process. The interaction of investment and technological change constitutes a major guide to future policy. The earlier distinctions between capital investment and technological change as separate causes of growth need to be modified in favor of a view that sees them as largely parts of the same process. It is in this broad sense that technological change probably has been the main cause of as much as 70–80 percent of U.S. economic growth.

Technological innovation involves managing the reduction of uncertainty—both technical and commercial (economic). It is for that reason that

engineers, the agents of technological change, require, in addition to a sound science base, abilities in design, management, and economic judgment. It seems evident from the worldwide slowdown since the early 1970s that managements and engineers everywhere have been confronted by much greater uncertainty about the business environment and have been compelled to expend much effort in dealing with it. This uncertainty included not only the energy crisis but also adverse macroeconomic policies by many nations, the collapse of the Bretton Woods fixed currency exchange rate system, the Vietnam War and its consequences, inflation and inflationary expectations, new sources of competition, and other changed circumstances from the relative tranquility of the earlier postwar years.

Thus, to improve the erratic and unsatisfactory growth rate of the U.S. economy, the major prerequisites are increased capital investment of constantly improving quality, increased training and skill of the total work force, and increased investment in R&D. These all interact with each other and are complementary. But they will not be easy to obtain without a favorable economic climate for long-term steady growth.

THE WORLD HAS IRREVOCABLY CHANGED

A most notable change in the past two decades has been the extraordinarily rapid diffusion of technology to many other countries, including those with wage rates a great deal lower than those of the United States. A century ago, transfer of technology from one country to another took place over many years; today it may be a few years or even months. But now that industrial technology has taken root in many new places, many countries no longer depend on the technical progress of just a few industrialized nations; they have become serious new competitors. This is a historic upheaval.

Such diffusion and its consequences pose immense new difficulties as well as opportunities for the United States. It has posed particular problems for managements brought up in the earlier postwar years when the United States had the world markets as well as a pent-up domestic market to ensure ample aggregate demand for anything that could be made—even cars with no more than novel tailfins. But today’s managements, particularly in the manufacturing sector, face quite a changed world scene. Many, but by no means all, have coped quite well, such as by spreading their operations across international boundaries, and thus insulating themselves against the varying national policies that affect operations in particular countries. The recent cost-cutting efforts of many managements display a sharp awareness of the challenges from competitors. Such efforts suggest the presence of significant long-run strategic vision of how their companies must grow and compete. They must now do even better. Those companies that have not or do not recognize this will either be taken over or disappear. Indeed, in the past, the

successful entrepreneurial exploitation of new technologies to create new products, processes, and businesses has been America’s distinct comparative advantage. Now, the greater number of international competitors poses greater challenges to the United States.

Markets for goods and services are now global. Many countries are competing vigorously with the United States in advanced technologies such as electronics, space, nuclear power, chemicals, and autos, producing products that often are of better quality, greater reliability, and lower price. In addition, financial markets penetrate everywhere and impose their own discipline on countries’ policies. Trading in financial assets far exceeds trade flows in goods and services (perhaps more than $50 trillion per year versus $3 trillion). The financial system of the world has become international, while the individual monetary, industrial, fiscal, trade, and labor systems remain national.

American wage rates have traditionally been high, although exact comparisons depend significantly on the exchange rates, productivity rates, and inflation rates. Many countries such as Brazil, South Korea, Mexico, and Taiwan still have much lower labor costs and are increasing their productivity faster in a catch-up process. If the United States is to maintain a higher-wage economy, it must raise its growth rate, its productivity, and its rate of innovation. Clearly, the United States is no longer a largely isolated economy and has lost the power to control its destiny virtually unilaterally. Its growth rate now depends to a much greater degree on its ability to compete successfully in international markets, especially in manufacturing, the most exposed.

THE KEY ROLE OF MANUFACTURING

Despite the fact that manufacturing now employs only 20 percent of the work force and has maintained over the long term about a 22 percent share of real GNP, it is exceptionally important to the U.S. economy because:

-

It performed about $85 billion out of $88 billion spent by the total private business sector in R&D in 1986, virtually all of the applied R&D of the United States.

-

It provides the major component (two-thirds) of the foreign trade of the United States, which consists of about 8 percent of GNP as exports and 12 percent as imports. The combined value of these two figures was only 8 percent in 1970. The same handful of companies, primarily those exposed to foreign competition, dominate both R&D spending and exports (Table 1), and they are, on the whole, among the major investors for increased competitiveness.

-

The manufacturing sector purchases a large part of the output of the service sector, which reciprocates.

TABLE 1 America’s Leading Exporters and R&D Spenders, 1986 (in order of size)

|

Exportersa (1986—Over $1 Billion) |

R&D Spendersb (1986—Over $500 Million) |

|

General Motors |

General Motors |

|

Boeing |

IBM |

|

Ford |

Ford |

|

General Electric |

AT&T |

|

IBM |

General Electric |

|

Dupont |

Dupont |

|

Chrysler |

Eastman Kodak |

|

McDonnell Douglas |

United Technologies |

|

United Technologies |

Hewlett-Packard |

|

Eastman Kodak |

Digital Equipment |

|

Caterpillar |

Boeing |

|

Hewlett-Packard |

Chrysler |

|

Allied-Signal |

Xerox |

|

Digital Equipment |

Exxon |

|

Philip Morris |

Dow |

|

Occidental Petroleum |

3M |

|

Union Carbide |

Monsanto |

|

Westinghouse |

Johnson & Johnson |

|

Motorola |

McDonnell Douglas |

|

Raytheon |

|

|

Archer Daniels Midland |

|

|

General Dynamics |

|

|

Total: $56.8 billion U.S. merchandise exports |

Total: $23.59 billion R&D expenditures |

|

aSOURCE: Fortune, 20 July 1987, pp. 72–73. bSOURCE: Business Week, 22 June 1987, pp. 139–159. |

|

-

Productivity improvement in manufacturing has been historically higher than that of the service sector, contributing heavily to the overall growth and wealth of the economy and helping hold inflation down.

-

This sector produces material essential for national security.

It is because of these features that concerns exist about the ability of U.S. manufacturing firms to remain competitive, especially in the case of the many small firms that contribute so much to manufacturing. Nevertheless, spurred by this competition, American manufacturing has been improving its productivity markedly. Labor productivity grew by more than 3 percent per year between 1980 and 1984, and is still growing at close to that rate, in contrast with a 1.5 percent rate in the 1973–1980 period. True, Japan experienced a 5.9 percent productivity growth rate during the 1980–1984 period, slipping to a 5 percent rate more recently; but many American firms

are responding to the competitive conditions, aided by U.S. economic policies of the recent past, which also partially favored new investment.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE NEW TECHNOLOGIES TO FIRMS

A highly significant long-term trend is the increasing impact of the information age on the entire economy, which is changing the nature of manufacturing itself. In fact, this new information-processing industry, when joined with the new technologies of automation, represents at least as fundamental a change in the economy as electrification did in the early twentieth century. It may well be the precursor of a new Industrial Revolution. The impact of this new industry on the rest of the economy is only beginning to be felt, and it will doubtless be some time before its effect on productivity improvement is fully realized. Such lags are not at all unusual in the case of such fundamental innovations. Thus, in the early decades of the twentieth century, business sector productivity failed to grow significantly, at a time when many technological changes were occurring. Not until the early 1920s did the productivity increases begin to occur. The introduction of the assembly line and the electrical motor produced 20 years of upheaval in industrial organization and management strategies. It was the combination of associated institutional changes (including educational, legal, and financial systems) and entrepreneurial creativity that eventually led to rapid productivity growth in the business sector. In the process, not only institutions and organizations had to change; a great deal of existing capital was rendered obsolete. The energy cost changes in the 1970s had a similar effect.

Coupled with this transition are the new technologies now becoming available. The next great wave of technological innovation is rolling in—in physics-, chemistry-, and biology-based industries. These new technologies can be rapidly employed to introduce higher value-added products and services, which is a sensible prescription for America in a world that offers increasing competition from economies with much lower wage rates. Higher value added means higher value added per worker. The point is that sectors where each worker has a high value added are sectors where there are extensive inputs of capital per worker—both tangible and nontangible capital. In such sectors even a high wage still constitutes only a small part of the total cost of production. Only in this manner can the outflow of U.S. jobs be arrested and reversed while the standard of living is improved.

There is one essential prerequisite for an economy to succeed with a strategy such as that proposed here: Capital in all its forms must be abundant, cheap, and of increasing quality. This in turn means pursuit of policies that encourage high rates of savings and capital formation and enhanced education, training, and research and development. This, as noted above, is exactly what the Japanese have been doing, and they have been doing it

much better than the United States has. These prerequisites can be recognized as the key components of Boskin’s (1986) prescription for sustained growth.

In summary, the American manufacturing industry must now move even more rapidly into higher value-added, more technologically sophisticated products made by more technologically sophisticated processes within more flexible organizational structures, and away from commodities that can be made more cheaply abroad, if American living standards are to be preserved and improved. American manufacturing must become more competitive by becoming more technological, which also means more capital- and skill-intensive; and the service sectors, especially those connected to information technology, must do the same. Commodity manufacture can be successful, however, where the large domestic market permits the use of favorable plant scale, especially if coupled with advanced technology. On the other hand, flexible automated manufacturing may reduce the economies of scale and aid smaller companies in their ability to compete. Even where the bulk of the value added is in marketing, sales, and distribution, large amounts of capital are still required with close feedback to manufacturing. R&D-intensive companies are themselves capital intensive, because R&D is a long-term capital investment.

This formulation of the American imperative reflects a basic shift in international trade from the situation where countries and industries could count on long-term stable comparative advantages to a dynamic state, in which comparative advantages are constantly being altered.

THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

There is still vast ignorance in American society about the forces which fuel growth, as well as antitechnology influences (especially noteworthy today in biotechnology). The public must be made aware of what really is at stake in a technologically intensive competitive world economy and, particularly, that competitiveness is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for economic growth. It is not an end in itself, but a means to improve long-term growth rates, the American standard of living, and quality of life.

What else can government do effectively? Government cannot decree a successful growth strategy, but it can better coordinate its various policies if it understands the real goals involved and promotes the infrastructure that the private microeconomy requires for innovation. The basic R&D function and the provision of safety nets for the unfortunate and those unwillingly excluded from the growth process are among these activities. Some regulatory activities are essential, although they can also be inhibiting. Foremost among the services that governments can provide is a better educational system. Although many skilled workers of today may not be able to adapt well to the new technologies, the younger generation can be trained to be far more

adept at employing them. But continuing education is becoming more important everywhere.

THE MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT FOR GROWTH AND COMPETITIVENESS

Although there is good reason to be skeptical about the ability of government to make intelligent decisions in specific markets, there is a great deal that government can do in providing a more favorable environment for business decision making. If the roller coaster economic experience of the last 20 years has proved anything, it is that long-term real growth is brought about by change and improvement in the microeconomy. A macroeconomic program, directed at controlling economic fluctuations by fiscal and monetary policies, primarily affects short-term growth. Nevertheless, some macroeconomic policies, such as high interest rates and therefore high cost of capital, may have a long-lasting impact on the microeconomy, for better or worse. It is important to recognize this interaction in setting macroeconomic policy, so as to improve long-term growth prospects. This is particularly important with respect to the volatility of macroeconomic policies.

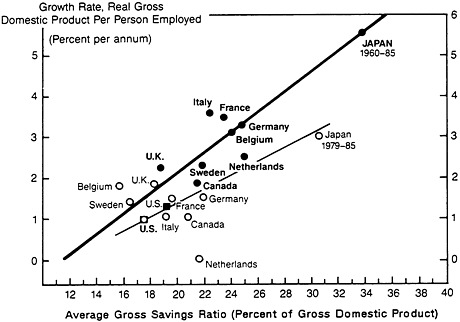

The complementary and interrelated nature of capital investment used by well-trained people and based on the latest technology has been argued in this paper. Unfortunately, the American savings rate from which such investments can be made is low in comparison with the rates of its principal trade competitors in East Asia. Boskin has shown that the savings rate of the Japanese, depending on how it is measured, is from two to nearly three times that of Americans (Boskin and Roberts, 1986). It is estimated that net domestic U.S. investment in 1986 was funded only 50 percent by net national savings; 50 percent came from foreign capital inflows. Japan’s high savings rate provides that country with a much lower cost of funds, permits heavy domestic investment as well as export of capital to other countries, and a “patient money” approach toward investment and R&D. If the cost of capital in Japan is half of that in the United States, as it appears to be—and it is much more abundant—then their horizon for decision making can be twice as long! This is the real Japanese comparative advantage, and is exemplified in Figure 2, which shows the resulting high productivity growth. This high savings rate is a postwar phenomenon and was carefully designed by encouraging tax-free savings and other measures. In addition, Japan has a high educational base and a number of unique societal institutions that shelter firms against risks and allow them to undertake large, long-term projects.

By contrast, postwar U.S. economic policies have generally favored current consumption over investment, which is likely to result in the reduction in the rate of increase of consumption and standard of living of future generations. In recent years, this has been accomplished by a fiscal policy of

FIGURE 2 National rates of savings and productivity growth, 1960–1985. Gross domestic product includes personal, business, and government savings. Symbols: ●, 1960–1985; ○, 1979–1985. SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (Courtesy of U.S. Department of the Treasury) (1986).

large government deficits (as much as 5 percent of GNP), accompanied by a tight monetary policy that has produced high real interest rates and a high cost of funds. The dollar consequently became overvalued and converted a small overall trade balance in 1981 to an annual deficit of perhaps $140 billion currently, injuring numerous American companies and industries. Although the dollar is much weaker against the Japanese yen and the German mark since the intervention by the finance ministers of the five major Western countries, it is still almost unchanged against the currencies of many American trading partners, such as those of Canada and South Korea.

Debt has accumulated at all levels at an accelerating pace, so that it now costs companies nearly 40 percent of cash flow to service debt versus 30 percent a decade ago and less than 20 percent in the 1960s. Interest on government debt has risen from 7 percent of public spending in 1975 to 14 percent today. Consumer installment debt service is now nearly 18 percent of personal income versus 12 percent in 1975. Total public and private debt in 1986 was more than 200 percent of GNP, up from 163 percent in 1975 and 174 percent in 1980. Some of this debt has gone into mergers, acquisitions, takeovers, restructures, and leveraged buyouts. Most have the effect of substituting debt for equity, a tactic favored by the tax laws, which allows deducibility of debt interest by corporations but not dividends. The U.S. Treasury in effect pays the premium that the stockholders of undervalued companies receive. Sometimes the resulting company becomes more effi-

cient; and restructuring, with or without takeovers, has produced major gains in efficiency and cost control in American manufacturing, contributing significantly to inflation control. More often, only the existing shareholders benefit (in the short run) and almost everyone else loses. The large debt cited above has not gone sufficiently into productive investment but has generated excess liquidity in the financial markets. Inflation in the 1980s is a financial phenomenon.

The United States is now an international debtor, and the longer the deficit continues, the greater the trade surplus will have to be in the future to finance the debt. With thinner cushions against economic downturn resulting from the increasing debt leverage, risk taking is discouraged or becomes foolhardy—not a climate conducive to gaining long-term competitive advantage or conducting long-range R&D or investment. The danger of recession and the consequent increase in the budget deficit is all the greater because government has already used up most of its fiscal and monetary stimuli. Furthermore, foreigners will at some point cease financing the American deficits. In 1986 the excess of spending over domestic production was more than 3 percent of the gross domestic product, and virtually all was financed by borrowing from abroad. This is unsustainable, and when foreign lending diminishes, the standard of living will inevitably decline: Capital for investment will become scarce because of the low net savings rate. Faced with such seemingly intolerable conditions, the government would be sorely tempted to monetize the debt, and with it, reduce its foreign debt while restoring price inflation as a potentially less painful way to reduce consumption. History suggests that, although there may be some favorable short-term effects, for example in employment, the long-term effects may be very unfavorable.

Science and technology, which require long time horizons, are bound to be undervalued in a short-term financial climate, which also favors financially oriented managers over engineers in promotions and salaries and short-term R&D projects over longer-term work, which might produce real breakthroughs. Inflationary expectations produce very short-term horizons indeed.

There was another side to this pro-consumption policy in the late 1960s and 1970s, when the surge of the baby boomers and women entering the job market crested. Because capital was relatively scarce and expensive and these new less-skilled workers were relatively cheap, the baby boomers and women flooded into the service industries, particularly into smaller companies, which play a vital role in new job creation. The result was an extraordinary boom in jobs (Table 2), wherein the United States did much better than its principal rivals. Europe still has much higher unemployment because of its greater labor and institutional rigidities. But, of course, the productivity of the American economy as a whole suffered by comparison, because policies were not in place to promote more of both jobs and productivity. In effect, American manufacturing remained competitive throughout the 1970s by keeping real

TABLE 2 Civilian Employment, in millions

|

Year |

EECa |

EECb |

United States |

Japan |

|||

|

1955 |

|

101.4 (est.) |

|

62.2 |

|

41.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

+3.4% |

|

+14.3% |

|

+12.9% |

|

1965 |

|

104.8 (est.) |

|

71.1 |

|

47.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

+0.5% |

|

+20.7% |

|

+10.4% |

|

1975 |

121.8 |

105.4 |

|

85.8 |

|

52.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

+4.1% |

|

+24.9% |

|

+11.3% |

|

1985 |

121.0 |

106.5 |

|

107.2 |

|

58.1 |

|

|

1986 |

121.5c |

107.1c |

|

109.6 |

|

58.5 |

|

|

Net increase: |

|

5.7 |

|

47.4 |

|

16.6 |

|

|

a12 members. b10 members. cEstimate based on 20–25 percent of total. SOURCE: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and European Economic Community. |

|||||||

wages down and reducing profit margins, thus compensating for the lack of new, and the lower cost of, production capital investment. The corresponding inflation masked the declining competitiveness because prices were raised by firms faster than real wages were adjusted. Even so, the last year of a positive merchandise trade balance was 1975; it averaged a negative $40 billion or so until 1982, when it began its plunge to a record $170-billion deficit in 1986.

So, from the early 1980s on, the American manufacturing strategy of the 1970s was ended by the strong dollar; firms were exposed to world deflationary trends and could not mask inefficiencies. The process of recovery, which entails adopting new technologies to regain a competitive edge, will be both expensive and perhaps even destructive of some jobs, of companies, and of certain industries that cannot realistically expect to restore their lost competitiveness.

However, the demographics are also changing—the baby boom is over. The labor force grew at a rate of 2.9 percent in 1976–1980, but currently it is growing at 1.8 percent, and the rate of growth is declining. Meanwhile, managements invested heavily for almost two decades in information technology, which will be required as skilled labor becomes scarcer and more expensive, rather than in assembly line capital. As a result, the ratio of capital to labor rose rapidly in the information sector, while capital per industrial worker stagnated. Nevertheless, the effect of information technology investment shows up in the recovery of manufacturing productivity in the 1980s. The service sector should follow.

The time has come, therefore, for macroeconomic policies that would

favor large new investments in all sectors, both for replacement of obsolete facilities and for installation of the new technologies that would favor increased productivity growth while still providing for an adequate number of new jobs. Because foreign capital inflows of the past must be paid for by exports, this policy will require a major increase in U.S. savings. A trade gap means that a country spends more than it earns, which is identical to saying that it invests more than it saves. If prudent noninflationary long-range macroeconomic policy is to be followed, this would require a tighter fiscal policy (reduced dissaving by governments) and a looser monetary policy to supply the money for increased growth at lower interest rates, combined with sensible regulatory and legal policies and a tax system that favors investment. Such a tax system would more nearly resemble that of the Japanese in allowing essentially tax-free saving and lowering the cost of funds. Most economists concur that a consumption tax system of suitable progressivity would favor a higher savings and investment rate. The 1986 Tax Reform Bill is not such a system and will in fact probably increase the cost of funds. This is a disastrous trend when capital and its cost have become the principal factors in international comparative advantage and competitiveness. As noted above, this is the other side of the coin of technological innovation. The current talk of reducing the budget deficit by raising taxes begs this question; if new taxes merely reduce savings in the private sector while producing an equivalent gain in savings in the public sector, nothing fundamental has been accomplished.

Most probably, to avoid the risk of recession if the budget deficit is brought down too hastily, and of inadequate savings if the trade deficit is sharply reduced, both need to be addressed simultaneously. A beginning has been made, and there is a modest downward trend in the twin deficits as a percentage of GNP. If continued, a cheaper dollar could eventually reduce the trade balance deficit, while the net national savings rate would improve as government dissaving is reduced. The reduced trade deficit would permit domestic demand to replace the loss of demand brought about by lower government deficits, as would increased demand for American exports abroad. Finally, steps can be taken to improve the savings rate in the private sector, which is a much longer-term but essential problem. Such a “soft” landing would aid the entire world economy to continue to grow; in this way, the nations are not deadly rivals by virtue of productivity increases and they permit the world economy as a whole to grow—a positive-sum strategy.

If the United States falters in following such a benign pro-technical-change policy, it may fall into varying degrees of protectionism, in addition to the perils of inflation. The world’s military and financial stability may be undermined. The burden of low productivity growth is forced upon the consumers. The consequences will inevitably lower the standard of living and security of the American people, as it is a zero, or negative, sum game.

Other countries are sure to retaliate. The United States may then retrace the path of Great Britain. Although there is certainly room for selective trade actions to meet egregious examples of foreign protectionism in order to improve overall world trade and therefore growth, “managed trade always ends up being managed on behalf of special interests,” not the general public, as Paul Krugman (1986) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has stated. The purpose of such selective trade actions should be to open up other nations’ markets, rather than close those of the United States. Recently, the United States has been acting more vigorously to overcome perceived ingrained protectionism abroad and to counteract “dumping” at home, and has come to the conclusion that it can no longer afford to be the principal world locomotive of growth. The dividing line between such actions and counterprotectionism is a very fine one, however, and there are dangers inherent in such steps if injured interests can politicize the process.

Many in government are already using the concept of “competitiveness” as a code word for old-fashioned government intervention in industry, under which bureaucrats, politicians, and pressure groups try to protect failing companies and promote supposed “winners,” while in fact promoting mostly each other’s interests. It has also been widely noted that American institutions make it difficult to have a full-fledged industrial policy as advocated by some, but that may be a blessing in disguise. Government regulatory agencies tend to become the captive of special interests through the political process. The rapidly changing conditions imposed by the global pace of technological innovation will make it even more difficult for government to control or direct the private sector, and the interventionist role of the Japanese government in this regard has been exaggerated. As Daniel Okimoto (1986) of Stanford University says: “What lies within the [Japanese] government’s effective power is largely limited to the creation of a healthy environment for business growth….” If this is true for a Japanese government operated largely by a powerful, prestigious bureaucracy, under an essentially one-party government where the Finance Ministry has always been much more powerful than the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, how much more true is it of the American system of constitutional law, with a strong and increasingly intrusive court system, in a country with a largely powerless bureaucracy and two contentious political parties, and where the Secretary of the Treasury has always outweighed the Secretaries of Commerce and Labor?

In many countries, managed trade is no problem—the business interests and government tend to see things the same way. In the United States, that is not the case. Companies would soon lose touch with global technological and economic developments; LTV’s bankruptcy shows the damaging effects on the steel industry of the trigger price system. The absence of foreign competition would reduce the pressure on companies to excel and develop.

Protectionism might even extend to capital flows, as happened in the 1960s, which could seriously harm American growth and lead to a decline in the stock market, which has been buoyed by the inflow of foreign capital. Maintenance of American competitiveness in the long run depends on sustained increases in productivity. Effective actions to achieve this will be required in both the public and private sectors. For example, in addition to those measures already described, technologists in private companies may well be asking themselves whether new high value-added technologies can be developed that are not as capital-intensive as present technologies—perhaps even more knowledge based.

So, a positive-sum strategy boils down to this: Only if Americans become better trained and managed—and invest a great deal more capital and technology in both manufacturing and services—can the standard of living improve at an acceptable rate in a highly competitive world market. The United States has some real historically demonstrated advantages in such a competition, but it must take a longer-term view and pursue those seemingly unexciting few-tenths-of-a-percentage-point increases in growth rate each year.

REFERENCES

Abramovitz, M. 1956. Resource and output trends in the United States since 1870. American Economic Review 46:5–23.

Boskin, M.J. 1986. Macroeconomics, technology, and economic growth: An introduction to some important issues . P. 35 in The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth, R.Landau and N.Rosenberg, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Boskin, M.J., and J.M.Roberts. 1986. A Closer Look at Savings Rates in the United States and Japan. Working Paper No. 9. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute.

Denison, E.F. 1985. Trends in American Economic Growth 1929–1982. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

Jorgenson, D.J., M.Kuroda, and M.Nishinizu. 1986. Japan-U.S. Industry Level Comparisons 1960–1979. Discussion Paper 1254. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Institute of Economic Research.

Jorgenson, D.J., F.M.Gollop, and B.M.Fraumeni. 1987. Productivity and U.S. Economic Growth. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Kalt, J.P. 1985. The Impact of Domestic Environmental Regulatory Policies on U.S. International Competitiveness. Discussion Paper E-35–02. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Kendrick, J.W., ed. 1984. International Comparisons of Productivity and Causes of the Slowdown. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Publishing Company.

Krugman, P. 1986. A trade pact for chips. New York Times, August 10:F-2.

Lindbeck, A. 1983. The recent slowdown of productivity growth. Economic Journal 93:13–34.

Okimoto, D.I. 1986. The Japanese challenge in high technology. Pp. 541–567 in The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth, R.Landau and N.Rosenberg, eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 1986. Historical Statistics. Paris.

Solow, R. 1956. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics 70:65–94.

Solow, R. 1957. Technical change and the aggregate production function. Review of Economics and Statistics 39:312–320.