2

Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences

The health differences we have considered present a complex picture, with older adults in some racial and ethnic groups clearly disadvantaged, though not on every dimension, and other older adults healthier than one would expect from their socioeconomic status. These differences are rooted in a complex of interlocking factors. This chapter reviews some previous attempts to analyze the evidence on differences, attempts that lead to a comprehensive framework within which these factors can be viewed. This previous work suggests variations in disciplinary perspectives, as well as possible alternative interpretations. The next nine chapters then focus on specific factors and summarize the current state of the evidence that they contribute to racial and ethnic differences; we offer recommendations about the needed research in each area.

MAJOR FACTORS

The roots of health differences, according to the summary of a 1992 national conference on behavioral and sociocultural perspectives on ethnicity and health, lie in five broad categories of factors (Anderson, 1995):

-

macrosocial influences: culture, institutions and politics, media, socioeconomic status, residence, family;

-

behavioral risk factors that produce chronic disease: diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol;

-

risk taking and abusive behaviors that are related to infectious disease and injury: sexual practices, injury risk behavior, violent behavior, drug abuse;

-

adaptive health behaviors: coping strategies, protective cultural practices, social support; and

-

health care behavior: the utilization or avoidance of health care, health care seeking behavior, self-care practices, provider behavior, the doctor-patient relationship, adherence to medical regimens.

In this list, behavioral factors receive the most attention, though institutional and social factors are not ignored.

Other perspectives provide more differentiation among the nonbehavioral factors that produce differences. Hummer et al. (1998), for instance, distinguish

-

socioeconomic status: education, income, wealth, employment, and occupational status;

-

other social factors: marital status, marital transitions, social participation and support, nativity, religion; and

-

macrosocial environment: residential factors, household factors.

These factors are assumed to operate through sets of “proximate determinants” of disease and mortality, including behavioral, psychosocial, and biological factors and health care.

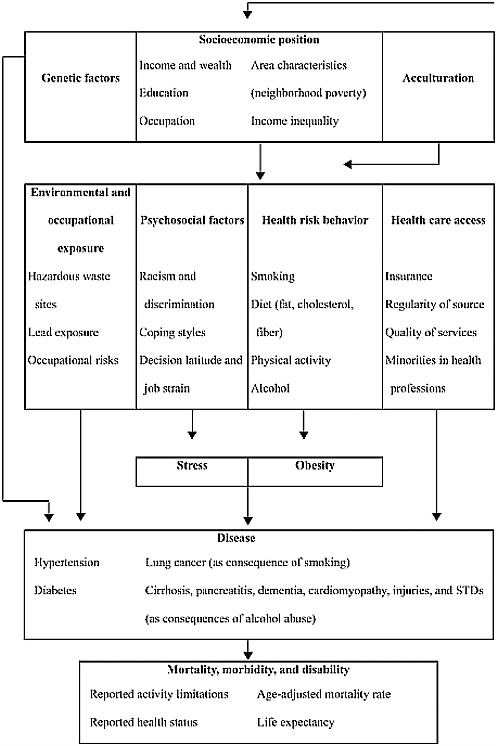

Different disciplines obviously emphasize different classes of determinants of disease. We did not seek to integrate these into a unified framework, but we do need a heuristic classification within which factors at the root of differences can be reviewed and research priorities assessed. A more complete starting point than the preceding lists is a review by Kington and Nickens (2001), who investigate racial and ethnic differences in health in the United States at all ages. They do not provide a conceptual framework, but in Figure 2-1 we represent the factors they review diagrammatically. These factors include those already noted and go beyond them. Genetic factors are added as relevant to specific disease differences. Acculturation is introduced as a factor that affects health risk behavior over time. Racism and discrimination are included among psychosocial factors, particularly as possible sources of stress. Stress is one of two broad physiological conditions—the other being obesity—that are discussed and can be assumed to partly mediate the effects of behavior and psychosocial factors on health. Kington and Nickens (2001) also note the possibility that disease and disability may itself affect socioeconomic status.

The rest of this section outlines the nine factors that are covered in Chapters 3-11. The second section of this chapter briefly discusses the issue

FIGURE 2-1 Factors in racial and ethnic differences in adult health.

NOTES: Most factors have a longitudinal dimension, affecting (and sometimes being affected by) health over the life course. Genetic effects on smoking are also noted by Kington and Nickens but are not represented.

SOURCE: Based on the discussion of Kington and Nickens (2001:253-310).

of evidence for the factors. The final section considers the critical and often overlooked issue of selection, which affects all studies and analyses of differences in health in late life.

Genetic predispositions underlie the mechanisms involved in health and disease, but whether these vary sufficiently by racial and ethnic groups is a question considerably complicated by multiple factors, such as the fact that racial and ethnic groups are not strict genetic groupings and the dependence of gene action on environmental factors. While some genetic variability across races and ethnic groups is tied to vulnerability to particular diseases (e.g., Neel, 1997), the variability within groups is considerable. Single-gene disorders make a trivial contribution to overall health differences (Cooper and David, 1986). Nevertheless, gene-gene and gene-environment interactions could play an important role in differences in specific diseases.

Among other factors, it is clear that socioeconomic status is implicated in racial and ethnic health differences. We have noted multiple dimensions of status recognized in the literature, chief among them education and income and wealth. The complications in the effects of status involve not only its reciprocal relationship with health, but also nonlinearities in its effects. For older persons, socioeconomic status over their lifetimes may be relevant for current health.

One possible route of influence of socioeconomic status is through health risk behavior, which covers such important factors as diet, smoking, exercise, sexual risk taking, and drug abuse. These behaviors may have an impact on health at specific stages in the life course, such as in adolescence, or may have a cumulative effect, in either case extending their influence into later life and affecting differences at older ages.

Possibly offsetting health risk behaviors may be positive factors: personal resources and social support may provide various ways of coping with unfavorable circumstances, such as avoiding physical or mental illness or mitigating its severity. For instance, religious involvement or a sense of personal control may contribute to psychological resilience and help avoid depression. To take another example, support from relatives or other caregivers is helpful in illness or disability, although the effects on differences are not necessarily straightforward.

While other people may contribute to an individual’s health through providing social support, they may also contribute to disease through prejudice and discriminatory behavior. Such behavior may also be characterized as racism, though we assume that it could be triggered not only by race but also by immigrant status, nativity, or religion. The roles of prejudice and discrimination may be broader than represented in Figure 2-1, since they can also affect such other factors as socioeconomic status, neighborhood conditions, and access to appropriate health care (e.g., Byrd and Clayton, 2002; Williams, 2001b). Researchers have focused more recently on the

possibility that experiences of prejudice and discrimination may have direct effects on health, which requires specific attention.

Stress is an important consequence of the experience of prejudice and discrimination. As suggested by Figure 2-1, stress can be treated as a separate factor, potentially mediating the effects on health not only of prejudice and discrimination, but also of other social and behavioral factors. It may, for instance, result from low socioeconomic status, and it may be alleviated by personal coping skills.

Figure 2-1 does not suggest any specific mechanisms to integrate the influences of all of these preceding factors on health. Relatively recently, various biopsychosocial mechanisms have been suggested that link environmental pressures, stress, psychological reactions, and physiological responses. While the investigation of these mechanisms has not so far focused strongly on racial and ethnic variation, the potential for insight into such differences merits separate discussion of this factor.

Health care is the final factor to consider. Several dimensions of care, as suggested above, might be relevant for differences: not only access to care, but also its quality; not only the behavior of health care providers, but also patient adherence to medical regimens; not only health care seeking behavior, but also self-care practices. While socioeconomic factors may be important in variations in health care use, other cultural factors specific to racial and ethnic groups, as well as geographic and other variation in health care, may also be involved.

All of these factors may operate at different points in the life course and also have direct effects on health in late life. The life-course perspective is discussed in the final chapter on factors. It is important for understanding late-life differences, many of which may have their origin in experiences early in life, perhaps in childhood or even infancy. A life-course perspective does not identify additional factors responsible for differences beyond those already noted, but it focuses on their operation at different stages in life and on the long-term effects. In discussing all the factors, therefore, we do not focus narrowly on their operation in late life but more broadly on their operation over the life course, with implications for late-life differences.

NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

As the study of racial and ethnic differences in health has moved away from descriptive studies towards trying to identify the underlying determinants of these differences, researchers have naturally become increasingly interested in developing models of causal processes.

Establishing causality in the social sciences is very difficult at best and in some cases impossible. A basic constraint is that the effect of anything (but say, for example, a series of stressful events) on health cannot be

established without invoking some minimum assumptions or restrictions. This is because of the impossibility of observing the counterfactual (i.e., observing that individual if he or she had not been subject to that particular series of stressful events). Yet if we want to understand the impact of various policies or say anything meaningful about the relative importance of various determinants, we need to be able to make statements about plausible causality.

Even the best social science has important limitations. Good natural experiments are few and far between and it is difficult if not impossible to control for all relevant aspects of context simultaneously. Furthermore, much of the empirical literature apparently relevant to understanding the determinants of racial and ethnic differences in health is not based on solid experimental data but rather it is based on associations among observable qualitative and quantitative data.

Conversations on causality both within and across disciplines are not always easy (Bachrach and McNicoll, 2003; Moffitt, 2003). There is no settled and accepted set of principles for addressing causal questions within the social sciences and different disciplines have different levels of tolerance for various kinds of assumptions. Plausible causality is best established by combining clear models of behavior with high-quality data. Findings that have been replicated in a number of studies using a multiplicity of different approaches are usually the most convincing.

The evidence we consider on these factors comes from studies of different types—each with their own sets of strengths and weaknesses—reflecting not only the variety of disciplines interested in the nexus between health, aging, and race and ethnicity, but also the wide assortment of research questions that must be considered. To verify differences between groups, either reliable vital registration (for mortality) or large representative surveys are needed. To explain these differences, one approach that researchers take, understandably, is to investigate variables in the same large surveys. This has the presumed advantage that accurately measured differences are being explained, but it also has a number of disadvantages. The variables available may not include all those of interest, or their measures may not be the most appropriate. Racial and ethnic identification may be problematic. The racial and ethnic groups of interest, if they are minorities and have not been properly oversampled, may be represented by too few cases.

These disadvantages might be overcome with a survey specifically designed to investigate differences, but other disadvantages are inherent in studies that rely on analysis of data from even well-planned surveys. Such studies are nonexperimental, and interpreting the empirical associations that may be uncovered is not straightforward. Causal inferences drawn from such associations are hazardous. Relationships may be spurious: a given determinant and the health outcome under analysis may appear linked

because both are separately related to a third factor. This possibility is a familiar problem in survey analysis: it is often addressed by taking care to include, in a multivariate model, measures of other factors that may affect the relationship under study—such as measures of socioeconomic status because of how it varies across racial and ethnic groups. Researchers can never be certain, however, that they have included all such relevant factors.

Another problem is that the temporal ordering between a presumed determinant and the health outcome of interest may not be determinable from survey data. The possibility of reverse or reciprocal causation, as suggested in the relationship between socioeconomic status and health, cannot be excluded. This problem plagues cross-sectional surveys and can even be a problem in some longitudinal designs.

A third problem involves the universe of respondents under study. Health-related factors may modify the racial and ethnic composition of this universe, which would affect any inferences about health determinants based on samples drawn from this universe. This issue, involving what are referred to as selection processes, has already been noted and will be considered in more detail shortly.

The evidence about factors in health differences is not limited to survey work. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs are also possible for addressing some issues, though not all. Not amenable to experimental study are such questions as how much prejudice and discrimination (with their potential health effects) are experienced by different racial and ethnic groups. However, experimenters do sometimes find ways to manipulate the experience of prejudice or discrimination or create laboratory analogues to such experience (Harrell et al., 2003) in order to assess the health effects. Such experimental studies have their limitations, in a sense the obverse of those of survey studies. One may question whether any specific experimental treatment can duplicate actual experience, particularly the cumulation of experience over a lifetime, and whether the small samples typically available to experimenters can provide findings that generalize to often heterogeneous racial and ethnic groups. In addition, experimental subjects may be college students rather than older persons, making the applicability of findings to older populations uncertain.

We consider in the next nine chapters the variety of studies that have been done on each major factor, trying to take the quality of the evidence into account. We note, where it is appropriate and not obvious, where conclusions are based on nonexperimental evidence or, contrariwise, on experiments of limited scope. These are not the only methodological issues, however. Issues of ethnic identification and measurement have already been noted. We will shortly consider selection issues, which could call into question findings from either survey or experimental studies. In this short summary of a diverse literature, we cannot provide a thorough method-

ological critique. The reader is referred to National Research Council (2004) where some specific factors and studies are treated in more detail.

SELECTION PROCESSES

Any analysis of racial and ethnic differences in health must take into account the effects of selection processes. Groups being compared will always be selected in some sense: for instance, they will necessarily be made up only of those who survive to the time of the study. This selectivity affects comparisons of group health, and it should therefore be explicitly attended to so that health differences are properly interpreted. (Selection, in the sense we use it here, is not the same thing as Darwinian selection and does not involve the evolution of genetic endowments).

Selection processes appear under various names in the literature, sometimes being referred to as unmeasured heterogeneity or drift and sometimes being labeled with reference to specific selection factors, as in “healthy migrant bias” (Abraido-Lanza et al., 1999). Related processes known as endogeneity or reciprocal causation are basically similar. The underlying processes, which can be represented within the same framework (Palloni and Ewbank, 2004), are potentially ubiquitous and need to be dealt with explicitly in interpreting health differences.

Selection Through Accession to Social Groups

Selection processes operate for any group—racial or ethnic, socioeconomic, religious, residential, or any other—if joining the group is dependent on factors that also affect health and mortality. Membership in the group may subsequently affect health, but initial selection into the group will have a separate, prior, and possibly large effect.

It is indeed possible to join a racial or ethnic group, by self-identification, for instance. This is perhaps most relevant for those of mixed ancestry who can choose their group. If healthier individuals self-identify with one group rather than another, that might not affect their health, but it will affect group health statistics.

A more important instance of accession to a group is immigration, through which one acquires, in effect, a new identity in a new society. The case of immigration provides a good example of a selection process, resulting in the so-called “Hispanic paradox.” As noted in Chapter 1, Hispanic immigrants in the United States are generally in better health than whites despite lower socioeconomic status. This paradox may be partly explained by the fact that immigrants who succeed in entering and staying in the United States seem to be drawn disproportionately from the ranks of those with better health in their countries of origin. This phenomenon is generally

known as the healthy migrant effect and appears to apply even more strongly to non-Hispanic immigrants, who immigrate at greater cost from longer distances. This positive selection is stronger for immigrants of working age; weaker for children, who generally immigrate as dependents; and possibly even reversed for the oldest immigrants, who may move specifically to obtain medical care (Jasso et al., 2004).

Selection processes could also operate through socioeconomic factors, affecting groups differently and therefore having some effect on differences. For instance, individuals who develop disabilities early in life may be precluded from certain occupations. Poor health in early life may reduce the chances for higher education and more successful careers, which in turn affect health. Individuals may self-select into higher- or lower-status occupations: black children, for instance, aspire less often than white children to higher status jobs, which they associate with whites (Bigler et al., 2003).

In addition, the choice of a place of residence (whether the choice is personally made or forced on one) could lead to a selection effect if this choice is somehow related to one’s health status. Aspects of residential location or neighborhood, it is argued (Morenoff and Lynch, 2004), have consequences, represented in survey analysis by “community” or “contextual” effects on health that are additional to the effects of individual characteristics. Choice of neighborhood may therefore have implications for health and may also have some link to prior health. For instance, more successful members of a minority group (who are presumably healthier) may move into more integrated neighborhoods, which would mean that any sample based on geographical concentrations of that minority would miss these healthier members and be unrepresentative of the entire group.

Selection Through Survival

As shown in Chapter 1, the magnitude and even the direction of health and mortality differences between groups change with age. A selection effect could be at work. Assume, first, that individuals are heterogeneous with regard to at least one health-related trait. (The term used in the mortality literature for such unspecified, unmeasured traits as a group is “frailty.”) Then, a racial or ethnic group subject to a harsher environment than another group will lose more of its members, generally the more frail ones, over time. Gradually, this group will come to be dominated by individuals who have superior health. By some indeterminate age, the mortality disadvantage this group suffers from may diminish, or even disappear or be reversed (Manton and Stallard, 1984; Vaupel and Yashin, 1985; Vaupel et al., 1979; Yashin et al., 1999).

Such a change in mortality differences as a cohort ages is not the result of changes in behavior or environment, but simply the outcome of the fact

that, over a long enough period, only healthier individuals survive. Note that this process does not require any initial difference in health-related traits between groups or any difference in the distribution of such traits within groups. The groups could be, at the start, entirely identical in frailty; over the life course, they would have been subject to different environmental pressures.

A good example of this phenomenon is the so-called black-white mortality crossover (Manton and Stallard, 1984; see Figures 1-1 and 1-2 in Chapter 1) and similar apparent crossovers for other groups. These crossovers are not necessarily just selection effects, however. They may be partly due to data artifacts, such as a greater tendency among older blacks than whites to overstate their ages.

Besides its involvement in crossovers, selection through survival could affect other health differences, though most research has paid little attention to this. For instance, it is reported that blacks are more resistant than whites to hearing loss (Henselman et al., 1995; Jerger et al., 1986) and to immunosuppression after kidney and liver transplantation (Nagashima et al., 2001). Selection could have some role in such differences, but the possibility has not been investigated.

In a cohort studied from birth (or preferably conception) to death, one need not treat selection effects separately but could, in principle, incorporate in the analysis the appropriate traits and the environmental factors that vary across groups. However, analysis of any sample of adults—and especially a sample of older people—must deal with this as a selection problem. Thorough knowledge of and complete data on the relevant traits and environmental conditions that determine survival at younger ages would permit the analysis needed to remove the influence on group composition of selection through survival. Such knowledge and data do not now exist.

Reciprocal Causation

Reciprocal causation, unlike selection processes, operates during, rather than before, the period under study. One might in fact characterize selection processes as a type of reciprocal causation that occurs before the analyst can collect any data. Technically, both can be treated in the same framework.

An example of reciprocal causation is what is referred to as “salmon bias,” the return of immigrants to their countries of origin. Return migration may be occasioned by ill health, and, to the extent it is, leaves the remaining group apparently healthier. In such a case, comparing those who remain to groups of nonmigrants is misleading. This is especially a problem in studies of Hispanics. Hispanic return migration is relatively high, at least partly because Mexicans in the United States, in particular, have easier access than other immigrants to their places of origin, and their immigrant

status does not constitute a political impediment to returning. Salmon bias is the obverse of healthy migrant bias and tends to reinforce the Hispanic advantage.

Changes in health status could also affect decisions about labor supply, consumption patterns, and wealth dilution that alter social standing, giving rise to another type of reciprocal causation. For example, adults affected by a health shock may incur large out-of-pocket expenses and be unable to work. When antecedent health status affects labor force participation, occupation, or wealth in this way, comparisons of health status across groups become more challenging. This process may reinforce differences between groups, as low status in a particular group gives rise to poorer health, which in turn may limit income-generating activities. In addition, the reactions of different groups may vary. The magnitude of a shock induced by equivalent health events on individuals may differ across ethnic groups, who may be exposed to contrasting labor market experiences, dissimilar health insurance coverage, and different dynamics of wealth accumulation processes. If so, reciprocal causation may leave different imprints in the patterns of health and mortality of different racial and ethnic groups.

Some of the literature refers to reciprocal causation as “direct” selection (West, 1991). This sets up a contrast with “indirect” selection, a term this literature applies to selection through accession to social positions or through survival. These terms are confusing to use, but they do help emphasize the similarities between what we have labeled selection and reciprocal causation, the latter being different mainly by taking place during rather than prior to the stage of life under study. For instance, if one could focus only on a stage of life after all return migration had taken place, then salmon bias would constitute a selection effect rather than reciprocal causation. Similarly, the effect of health on socioeconomic status may be either a selection effect, if it takes place prior to the stage of life under study, or reciprocal causation, if it takes place during this stage.

Implications

All of these selection processes are produced by a similar mechanism in that the initial composition of a group is affected by prior health and mortality conditions. The health status of the group at any given time, therefore, should not be construed as resulting solely from factors that spring from group membership. To infer the effects of group membership, one would need to remove the contribution of prior health conditions that influence membership. In order to do this, one would have to introduce factors responsible for selection into any model for interpreting racial and ethnic differences.

These selection processes should not be considered as distorting some deeper reality. The Hispanic mortality advantage, for instance, is not an illusion and is not negated by the possibility of its being rooted in selection. Rather, to the extent the selection explanation is correct, this advantage needs to be properly interpreted. The inferences to be drawn from observing such facts may not be the obvious ones. One should not assume advantageous Hispanic cultural practices or favorable behavioral profiles. By the same argument, the convergence of black and white mortality in old age (after removing the effects of data errors) is not an artifact or mirage. But because it may be partly due to selection, it does not necessarily mean either that older blacks are taking as good care of themselves or receive as satisfactory health care as whites.

Different selection processes can occur together. For instance, health differences between immigrant groups and the native population will be affected by both migration selection and survival selection (Palloni and Morenoff, 2001; Swallen, 1997). The initial immigrant advantage in mortality could expand, before contracting at the oldest ages. An increasing short-term advantage could occur if immigrant groups rapidly lose their most frail members as a result of exposure to unfamiliar risks, while native groups experience only average losses of frail individuals.

The literature on race and ethnic adult health differences tends to play down the importance of selection processes, when they are recognized at all. The exceptions are few (Adams et al., 2003; Fox et al., 1985; Goldman, 2001; Palloni and Morenoff, 2001; Power et al., 1986; Smith, 1999; West, 1991). The potential damage from such neglect of selection processes could be large and significant (Adams et al., 2003; Ewbank and Jones, 2001; Goldman, 2001; Jasso et al., 2004; Palloni and Ewbank, 2004; Palloni and Morenoff, 2001; Smith, 1999). The stronger the association between prior health status and membership in a group, the larger will be the selection effects. The larger the intergroup difference in the variance of unmeasured traits affecting mortality or health status, the larger will be the influence of heterogeneity. Selection effects may also wane, remain invariant, or increase over time, considerably complicating interpretations of trends in health differences (Goldman, 2001; Vaupel and Yashin, 1985).

To deal with selection processes, one has to avoid treating them simply as nuisances or threats to the validity of a study. Instead, they should be considered part of the reality under investigation. Models that represent the relationships of interest should incorporate selection processes to the extent possible. There are a number of ways of doing this (Palloni and Ewbank, 2004), though in most cases there are strong data requirements and stiff constraints on the inferences that one can draw. Nevertheless, researchers should at least be able to set bounds on the uncertainty surrounding inferences and conclusions.

NEEDED RESEARCH

Selection processes could create or exaggerate differences, or they could offset or disguise them. Identifying and analytically accounting for selection effects (and reciprocal causation) is a substantial, continuing, task. Researchers should either adopt strategies that attenuate some of the associated distortions or, at least, qualify the inferences likely to be drawn. But first they need to recognize the problem and define its reach. Research on health differences in old age should consistently consider the possible operation of selection processes. In most cases, a model representing the genesis of health and mortality differences should include a proper representation of selection processes. To understand and better model selection, research directed at this issue is also advisable.

Research Need 4: Identify and quantify the various selection processes that affect health differences among racial and ethnic groups.

The key reason for the neglect or superficial treatment of selection is the lack of information about the processes underlying it. What data and how much of it should be collected depend on the pertinent selection processes and on the availability of alternative procedures to account for their influence. A good example of the additional information that can be collected involves immigrant surveys that follow individuals from their places of origin to their destinations and through the assimilation process, tracking changes in health, socioeconomic and political status, and other factors (Jasso et al., 2004). (Other suggestions about alternative data collection strategies to account for immigration selection are given by Palloni and Morenoff [2001].)

In particular cases, the data needed could be obtained through modifications of conventional study designs to promote a broader range of comparisons. To understand immigrant selection, for instance, one needs to be able to compare movers and stayers in the origin population, possibly even comparing migrants with siblings, relatives, or in-laws. A transnational study design, though it involves logistical and financial obstacles, is therefore far more useful than a study design based only on the receiving population.

With appropriate data, models could be formulated to yield ranges of estimates for differences as well as confidence intervals. A number of estimation procedures do exist for dealing with a reduced class of selection processes. These should be deployed judiciously, if not to adjust estimates of differences to account for selection processes, at least to provide an idea of the sensitivity of these estimates to assumptions about selection. It is always better to supply information about uncertainty, even if this blurs the scientific conclusions, than to convey the impression of robustness while ignoring potentially relevant effects.

Models should be specifically formulated to allow selection factors to vary in their effects over time. Extant models allow for unmeasured traits to affect selection, but they rest on the rather unyielding and excessively restrictive assumption that these traits and their effects are time-invariant. Fixed traits are surely important, but they may be only a small subset of the relevant factors for health and mortality differences. Since little is known about the magnitude of errors caused by deviations from the assumption of invariance, it is difficult to evaluate whether choosing an incorrect model for selection may lead to more serious problems than ignoring it altogether. More research is needed on the nature, advantages, and shortcomings of models with time-varying effects (Weitz and Fraser, 2001).