3

Boundary-Crossing Technology Networks at Degussa

Karin Bartels

Degussa Corporation

OVERVIEW OF DEGUSSA

Degussa is a newly formed company with an old name. In 2002, Degussa had sales of about 11 billion euros and operating profits of about 1 billion euros. It employs about 46,000 people worldwide and focuses on specialty chemicals that have higher profitability and are less cyclical. The old Degussa was known more or less for its precious-metals and catalyst business. The new company is Germany’s third-largest chemical company and considers itself a world market leader in specialty chemicals.

The current trend in most chemical companies is not to make or sell new products but rather to sell system solutions to customers. That is the direction that Degussa has taken. The company knows customers’ needs and how to solve challenges, and it provides the appropriate expertise and technical solutions for customers. Degussa typically does not provide end-user products; rather, it makes intermediates that are unrecognizable in the products that people use but that contribute to their performance.

The current Degussa evolved by merging several German companies over the last 3 years. The old Degussa merged with Huels, forming Degussa-Huels in 1999. In the same year, SKW Trostberg acquired Goldschmidt, forming SKW. Degussa-Huels and SKW later merged to form the new Degussa in 2001. The legal entities involved in all of those companies with different cultural backgrounds also came along. Initially, it was quite a challenge to combine all the company cultures and business strategies, and a lot of progress has been made in forming the new Degussa represented in its vision: everybody benefits from a Degussa product, every day and everywhere.

SALES

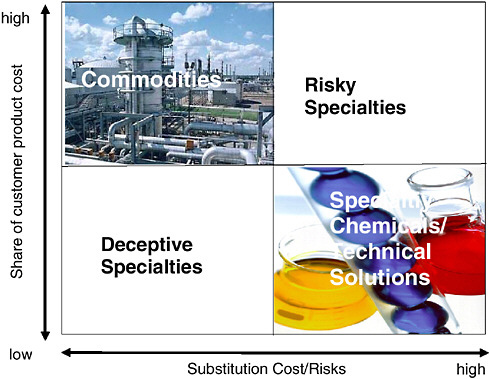

The portfolio chart in Figure 3.1 shows that commodities substitute for cost-risk factors. Substituting a commodity is more or less low risk, but if it is done with specialty chemicals, they typically have unique applications and compositions, and the cost-risk substitution ratio becomes very high.

Some 40 percent of Degussa’s sales are in highly specialized technical solutions. Deceptive specialties make up 27 percent. The latter may include hydrogen peroxide and carbon black, which are often thought of as commodities. However, producing these chemicals and turning them into solution systems are technically much more demanding than people think. The risky specialties are currently at 14 percent and the commodities 19 percent of sales.

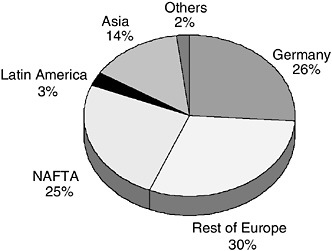

As shown in the sales distribution chart (Figure 3.2), Germany accounts for only about one-fourth of total sales; almost 75 percent comes from abroad. That is common in multinational chemical companies: the majority of sales are not in the parent country.

DISTRIBUTION OF STAFF

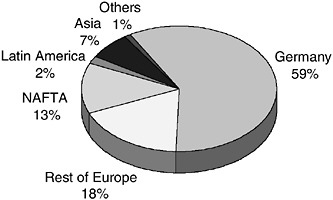

Doing business in other regions requires that the company manages its workforce in an efficient and global way and that the company have bases in the region to be successful and sustain its competitive advantage.With regard to employees and R&D staff by region, most of Degussa’s R&D effort is centered in Germany (see Figure 3.3). One of the fastest-growing areas is Asia, particularly China.

This is an edited transcript of speaker and discussion remarks at the workshop. The discussions were edited and organized around major themes to provide a more readable summary.

FIGURE 3.1 Portfolio chart.

FIGURE 3.2 Degussa’s regional sales. NOTE: NAFTA = North American Free Trade Agreement Countries.

About 3,300 people work in Degussa R&D worldwide, and of those, about 13 percent are in NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) countries. Degussa’s R&D activities in the United States focus on product development, applied technology, and customer service. Degussa works very closely with its customers in all regions and emphasizes this strategy. Companies have to position the workforce in a way that is appropriate for market and customer demands in each region.

One of Degussa’s business goals was to have a larger presence in China—not just sales offices, but headquarters

FIGURE 3.3 Location of Degussa’s R&D employees. NOTE: NAFTA = North American Free Trade Agreement Countries.

in China or a site where all of China’s activities are coordinated. In November 2002, this goal was accomplished with the foundation of a holding company for China operations, Degussa (China) Co., Ltd. Now, more than 15 companies, including several joint ventures, operate production facilities in China. The broad array of high-quality products is aligned to customer needs not only in China, but all over Asia. Degussa works with both the local workforce and local companies, combining the knowledge and expertise that exist in the region with the workforce that Degussa brings in. For example, in the fine-chemicals field, where the company makes intermediates for the pharmaceutical industry, it has a manufacturing site in Nanning, China, and a sales office in India. A technical center in Shanghai will be inaugurated in January 2004.

The majority of Degussa’s workforce and the technical expertise is in Europe. The workforce is also being moved to the Americas and Asia. The goal is to initiate activities and then, once settled into a region, hire from the regional market. Degussa’s presence in the United States is strong in hiring chemists and chemical engineers to run production, R&D facilities, and technical centers.

Degussa finds that people are somewhat hesitant to go from the United States to other regions and is now encouraging people to get more experience by working in Europe or Asia. This effort is supported by offering cross-cultural training programs that are open to everyone but are mandatory for employees who are being relocated.

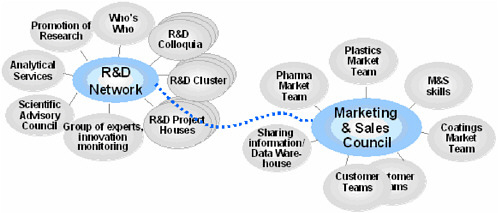

LINKING KNOWLEDGE

Linking knowledge is a large theme in Degussa, because of the company’s history, recent acquisitions, and evolution. Most of the research sites are still in Germany, the rest of Europe, and the United States, where many of the legal entities maintain their own production sites, product development, and technical support. It was decided to maintain sites that have a wealth of knowledge and technical expertise, which enable business units to provide customers with appropriate solutions for their needs. The challenge is to make accessible all the existing knowledge in the company, linking different businesses and sites. To learn from and transfer the existing knowledge, Degussa launched a Linking Knowledge project to form an R&D network worldwide (see Figure 3.4) and use the innovation platform and market proximity as integral parts of its entrepreneurial success.

One of the key issues is to link the R&D network with the market and sales groups and generate new ideas to transfer technology from one group to another without reinventing the wheel. There are regular meetings where these groups come together and discuss how to learn from each other. The project was launched nearly a year ago and has already made great strides in developing good ideas. To reward such team activities, Degussa recently launched a Linking Knowledge Award that encourages scientists, business people, and others in the company to work cooperatively and learn from other experts. Thus, this award is dubbed “Not Invented Here” because it encourages exploring existing solutions in other businesses, copying ideas, and adapting them for different applications. For example, a team comprising members of five business and service units in Germany and the United States received an award in the category “Best Technology Transfer” for its new concept and entrepreneurial work in promoting internal growth.

There are many ways to share information; the challenge is to coordinate them efficiently. Progress is being made, the system is in place, and people are communicating more effectively. As Degussa attempts to bring all the regions together, everyone is asked to share knowledge and communicate. The soft (interpersonal) skills are important, as is understanding that fresh ideas and different perspectives can result in better solutions. One of the focuses of Degussa’s worldwide R&D sites is to develop new products peculiar to the regional markets and customers’ needs. The company is present in regions where there is the largest growth and the potential to sustain a competitive advantage. To encourage innovation and creative ideas that lead to new products, new processes, and new applications for existing products, Degussa launched the Innovation Award right after the company’s foundation.

Some of the challenges are still present, and sometimes there is room for improvement; but when everyone works toward a common goal and embraces the global workforce concept, Degussa will succeed, given the highly trained employees and technical skills that its workforce possesses.

DISCUSSION

Karin Bartel’s presentation began a discussion about the globalization of the chemical workforce. Language and cultural barriers and collaboration among differing groups were discussed. The quality of new employees in the workforce was communicated and included continuing education, training, and the importance of high-order skills. Another topic was Degussa’s competence center in China.

FIGURE 3.4 Linking knowledge from Degussa’s R&D network.

Language and Cultural Barriers

Alvin Kwiram, of the University of Washington, asked what disadvantages executives or scientists in our U.S. corporations have when they try to interact either in Europe or in Asia. Should people in the United States worry about the language problems here, or is that not a problem at all because, even in a globalization context, so many other people speak English around the world?

Bartels thinks that language is not a problem here but that understanding a different culture is a problem. By going to a different country and speaking a different language, one has a greater chance of understanding the problems of that country. To do business on a global basis, she thinks it is necessary to pick one language and speak it, and most likely that will be English.

Bartels noted that in Germany there is a perception that there is not a big difference between Germany and the United States, but she thinks it is necessary to get away from that perception. There are differences, and they need to be identified and used to the greatest extent to create value for companies and to use the people in ways in which they can best exploit their skill sets. Some people have a strong technical background but lack interpersonal skills; they are needed, but it would of course be best to have people with the high-order skills and a strong understanding of technical subjects.

Robert Grathwol, of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, noticed the large percentage of Germans still being employed by Degussa. He wondered about a situation in which two very qualified candidates applied for a job and both were non-German but only one was competent in German. Who would be hired?

Bartels said that she would value the person that brings a different cultural background to the company. The company still tends to employ people educated in Germany, but Degussa wants to change that. One of Degussa’s missions is to become a truly multinational company.

Collaboration

C. Frank Shaw, of Illinois State University, commented that it seemed that all research is typically collaborative. He does not think there should be too much pessimism about the situation but rather a fostering of more collaboration. If there are some subdisciplines of chemistry in which collaboration is not common however, how can it be nurtured?

Bartels thinks that there is already awareness at the university level about breaking up the departmental structures and fostering collaboration among the various departments.

Douglas Selman, of Exxon-Mobil, brought up the obstacle that exists internally, even in a given culture, of the interface between the technical person and the business person. Technical people have learned and tend to collaborate almost naturally in their field and discipline internationally. It is the interface between the marketing person and the Ph.D. bench chemist or the manufacturer that poses the greatest challenge.

Continuing Education and Training

Donald Burland, of the National Science Foundation (NSF), noted that at IBM and other companies, there seems to be a move away from making things to providing solutions and systems. He questioned how this new direction is going to affect the kinds of people entering the chemical workforce and what sorts of jobs they will do.

Bartels thinks that what is needed is to have a well-trained chemist or chemical engineer that has knowledge about the fundamental fields of science. In addition, there is an increasing need to have background in fields such as materials science, nanotechnology, gene expression technologies, and DNA array areas. However, a university cannot do everything, and to build the additional skill sets that are demanded, companies themselves are trying to train engineers and chemists in additional skill sets that are needed.

Michael Rogers, of the National Institutes of Health, asked whether if one group needs to work with another group in another geographic area, Degussa provides the group with specific training in culture and language to be able to perform the job.

Bartels stated that Degussa has a cultural training program.

Higher-Order Skills

Matthew Slaughter, of Dartmouth College, pointed out that he has heard a lot of people say, in different contexts, that it seems that what is increasingly valuable for many multinational firms is not just technical skills, but also soft, interpersonal—or whatever phrasing you want to use—skills of combining people and ideas and creating value through the connections. If ExxonMobil is spending 10 years trying to teach people these skills, is there a sense that there is a problem in the higher-education system in imparting the skills to students in their formal training? If so, what would be ways to teach the soft or interpersonal skills that are so valuable?

Bartels thinks that the focus of the university is to educate people and impart knowledge. However, universities cannot do everything. They cannot teach major subjects and also make students good speakers with excellent interpersonal skills and communication skills. She said she is a bit overwhelmed by what is needed to be successful in the global environment.

Kwiram noted that one of the Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) programs at the University of Washington has a team approach that is unique in that graduate students coming in have to spend the first year working on a joint project as a team, and this work

becomes part of their dissertation. The students are enthusiastic about it, and it seems to be a promising type of program.

D. Michael Heinekey, of the University of Washington, noted that in the past, chemists were required to study German as part of their Ph.D. studies in the United States. The reason goes back to the time when the literature was mainly in German. The requirement has been dropped, and he thinks that might have been a mistake. He would not recommend that German necessarily be reinstated, but perhaps an Asian or other foreign language needs to be studied. He recalled that it had been suggested earlier that perhaps culture should be studied as well. Study-abroad programs exist in the sciences and engineering and, although they are not as developed as in the humanities, should be taken advantage of if even for a brief period. He said that students would then be advanced in soft skills that are not typically learned in school and that in general there has to be more of an international perspective in thinking about how to train students.

Bartels agreed and thinks that the interaction between academe and industry to offer internships for students should be increased in all parts of the world in which a company operates.

Marshall Lih, of NSF, provided a short answer to Slaughter’s question about teaching higher-order skills. In the middle 1960s, Dartmouth College offered an introductory course in engineering design. The course organized the students in companies to work on actual projects. The higher-order skills that people are talking about are learned by trying to solve a problem and working on a project, such as how to negotiate and how to organize a team. There is no room in the curriculum to teach a separate course, but one project course cannot cover everything. Motivation to learn afterwards is often provided.

Wyn Jennings, of NSF, added further information on IGERT, which is concentrating on the very issue of giving principal investigators and universities an opportunity to experiment with graduate education. The program includes multidisciplinary education; development of career, professional, and personal skills; and instilling a global perspective in which most of the students are, in fact, going abroad for a time. Will it take the student 6-8 years to do it? No. The students are graduating in the normal amount of time. People are accommodating the increase in learning, and the students are doing well in the job market. There are 116 sites working with IGERT in the United States, and a similar program is being implemented in Germany. In addition, workshops and seminars are career development activities that take less than a semester or quarter. Doing something new and exciting does not need to include a three-credit course for a semester.

David Budil, of Northeastern University, discussed how cooperative programs are supposed to help impart higher-order or real-world skills. He said that in some ways, this method is avoiding the issue of what educators have to do, because the students are being sent out into the real world and into industry with the hope that their training will take place there.

Returning to Slaughter’s question, Budil asked the corporations whether they could explain more about their training programs and how they would benefit if training were added to the educational program.

Miles Drake, of Air Products and Chemicals, Inc., responded that his corporation has coursework that people can sign up for. It includes the core skills of teaming, management, communication, and negotiation.

According to Bartels, Degussa has an international traineeship, in which students are brought in from companies and from the universities to be trained for higher management positions. The students should have both a business understanding and a technology bachelor’s degree—for example, in chemistry or chemical engineering. The students are put on trainee assignments for six months or a year to work in different regions where the company has operations and sales offices.

Competence Center

Miles Drake was interested in the underlying philosophy of the Degussa competence center in China.

According to Bartels, the Shanghai competence center involves about nine business units of Degussa that have gone there to develop new programs. They in a sense are receiving corporate funding to start their business. Degussa puts people from Europe or the United States in the competence center, and then the different businesses within the center try to hire local people. The centers work with universities and with Singapore and China. From the joint ventures, Degussa is trying to bring in and develop people with skills that are specific for the business unit’s needs.