1

How Do National Labor Forces Become Global, and Who Should Care?

Matthew J. Slaughter

Tuck School of Business, Dartmouth College

INTRODUCTION

The basic idea in economics and business is that firms tend to pay people according to their productivity. Labor unions and profit sharing are important, but looking at the big picture of the whole world over decades, they have not been as important as paying people according to their productivity.

In addressing how labor forces become global, I will discuss income, wages, and earnings, not unemployment. This is because the United States and comparable countries have adequately flexible labor markets. There are always business-cycle considerations, and in the United States there has been a business-cycle downturn in the last few years. The economy seems to be picking up now, but over the last couple of years unemployment rates have been higher than they were in the middle and late 1990s. People tend to be able to price themselves in the labor market. Therefore, it is more helpful, in understanding the forces that affect people in the labor market, to focus on earnings as opposed to how many people are working.

This presentation provides a quick survey of international economics to explore how labor forces become more global and what it means for the U.S. economy, its workers, and the chemical and allied enterprises in particular.

HOW LABOR FORCES BECOME MORE GLOBAL

In general, a number of key factors influence globalization of labor forces:

-

The number of people in a country who choose to be in the labor force,

-

The activities that firms choose in the country,

-

The prices that these activities get on world markets, and

-

The capital and technology used for the activities.

National labor forces become more global when cross-border flows—people (immigration), goods and services (trade), and capital and technology (foreign direct investment)—influence one or more of these four factors. These flows are relevant for understanding the integration of labor markets across countries.

Immigration—Flow of People Across Borders

Immigration influences other cross-border flows and affects the number of people choosing to be in the labor force. In much of the policy discussions about globalization, it is presumed that immigration matters most and that its economic impacts are obvious. People may say that if more people are in the labor force, wages will tend to go down. That is why some politicians think that immigration should be carefully controlled. In fact, the cap on H-1B visas (for temporary workers in specialty occupations) in the United States has been reduced by two-thirds, in part because of the presumption that too many skilled immigrants are entering the country and pushing particular occupational wages in the country down. Immigrants, however, constitute important flows of knowledge and capital across borders.

Back in the early 1800s, the textile industry was the high-tech, high-productivity industry—the most cutting-edge production activity in the world. Many countries had very strict laws on the export of that technology, either the capital goods or the knowledge embodying the technology.

This is an edited transcript of speaker and discussion remarks at the workshop. The discussions were edited and organized around major themes to provide a more readable summary.

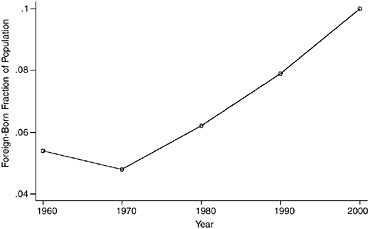

FIGURE 1.1 Foreign-born fraction of U.S. population. Note: Data for 2000 are estimated. SOURCE: Borjas et al. (1997, Table 1).

Much of the early production of textiles in the United States came about because people went to various places in England, worked in factories, and because they were not permitted to write anything down, memorized the structure of particular machines. They then came to the United States and were able to replicate the capital goods that they saw abroad. The early production in textiles in the United States was one of the main manufacturing activities that enabled the country to grow more quickly and was the direct result of immigrants’ bringing in the ideas.

More recently, there have been comprehensive surveys of startup companies in information technology (IT), especially in the Silicon Valley of California in the 1980s and 1990s. About one-third of startup companies in Silicon Valley between 1995 and 1998 were either started or headed by immigrants from India or China (Saxenian, 2002). In 1998, they headed 2,775 Silicon Valley high-tech firms, employed 58,000 people, and had total sales of $16.8 billion.

When we think about where new and creative ideas come from, reducing the number of immigrants potentially reduces the creative dynamism that generates new products and companies. The situation is more complicated than just simply allowing in more immigrant workers that put pressure on wages. Management flows in capital and in technology can influence much of what firms decide to do.

More immigrants are coming to the United States. The data points in Figure 1.1 are taken from the decennial U.S. population census (Borjas, 1997). The foreign-born fraction of the total U.S. population was at a minimum in 1970, and has been rising steadily since then. About one-tenth of the current U.S. population is foreign born. This trend has been driven, in part, by a change in U.S. immigration policy in the middle 1960s that oriented it toward considerations of family reunification. The figure does not detail the skill mix of the immigrants coming in. There has also been substantial variation in whom the United States is letting in, with respect to both the country and the individual states.

When coming to the United States, immigrants tend to go to the immigrant gateway states of California, Texas, New York, New Jersey, Florida, and Illinois. Between 1995 and 2000, about 60 percent of the 5.6 million foreign-born population who moved to the United States entered the country through these states (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). The total U.S. population in 2000 was about 281 million, and the foreign-born population was 31.1 million. To understand immigration, it is appropriate to consider California, because California, even among the gateways, stands out as a very attractive destination for immigrants.

The skill level of those coming to the United States is unevenly distributed, with many high-school dropouts at one end and many advanced-degree people at the other end. By 1990, 10 percent of people working in California were immigrant high-school dropouts. The estimate for 2000 is that the figure will be about 15 percent. At the other end of the distribution, California has attracted a disproportionate share of highly skilled people with Ph.D.s, M.D.s, and M.B.A.s.

With all the high-school dropouts coming into California, it would seem that the wages of less-skilled workers in California must have plummeted during the 1990s and on to today. An alternative is that firms, when they are faced with people with different skills coming in, choose to conduct different activities. California has absorbed the influx of people, and some industries have consequently grown in California more than in the rest of the United States. With a more-than-average number of less-skilled and more-skilled workers coming into the state, firms have in fact changed their activities.

Relative to the rest of the United States, the fast-growing industries in California over the 1980s were machinery (such as computers and office products), finance, insurance, real estate, and legal services, all of which are related to the IT boom and involve a high skill set. At the other end of skill intensity, California also had a boom in textiles and apparel. In Los Angeles County in 1980, there was essentially no production of textiles and apparel; by the end of the decade, the county had developed a thriving apparel and textile industry, whose production was second in magnitude only to that of the New York City area. Personal and house-hold services also saw a boom, and most of the employees were immigrants.

The absorption of immigrants is more dynamic than the presumption that immigrants are going to be bad for the native-born workers’ wages. Immigrants can bring in much additional technology and capital. Even if they do not, firms can absorb people through changes in the mix of output in ways that are not necessarily going to put pressure on wages. In fact, if one looks at the economics literature on immigration, it is difficult to find clear downward pressure on native wages averaged across all sectors due to immigration. That is true for the United States and for many other countries.

For example, in the early 1990s, there was a surge of Russians who left with the breakup of the Soviet Union and

headed to Israel—one of the biggest immigration shocks a country has ever seen. It is hard to find pressure on Israeli wages caused by all these Russians. They were absorbed by firms hiring them in industries such as IT on one end of the distribution and construction on the other; the Russians needed places to live.

Trade—Flow of Goods and Services Across Borders

Trade is another important globalizing influence. Even if borders are closed and immigration is not allowed, the labor markets can become integrated as goods and services flow across borders. For instance, textile production has declined in the United States, and this has had a lot to do with import competition.

Trade will affect the prices that activities fetch on world markets. As international markets become more integrated, prices that firms can charge in different countries can change, and this will have a direct impact on wages. A growing body of evidence in international business shows that trading goods and services is an important way for capital and technology to flow among countries.

Especially in the United States, the term “trade” often leads to a discussion of numbers of jobs. Those who do not like fair trade argue that international trade destroys jobs. Those who like international trade argue that international trade creates jobs. Both arguments are both right and wrong. International trade does not destroy jobs or create jobs. If we take a long-perspective (decades) look at living standards, the issue has more to do with the number of jobs in the economy rather than the kinds of jobs. Only through the simultaneous destruction of some jobs and the creation of other jobs can international trade on the average, benefit economies along the lines that economists are so fond of talking about.

From the economist’s point of view, international trade is on average a good thing for countries. The gains that economists talk about—a firm specializing along the lines of competitive advantage and consumers having wider choice—come about only when firms get out of some lines of business in a country. From the standpoint of the welfare of the United States it may be a good thing that firms in textiles and apparel and footwear shut down. It is only by releasing the people, capital, and technology that are in those industries and allowing them to move into industries such as chemicals, IT, and aircraft—industries in which the country is better than the rest of the world—that the gains economists talk about are accomplished. Overall, international trade both destroys jobs and creates jobs, and it is hard to find any evidence that it has any net impact.

However, the impact of international trade on labor markets is not uniform. Trade globalization tends to be good for countries on the average, but “on the average” is an important phrase. When countries, on the average, gain from trade, not every person, firm, or geographic region benefits

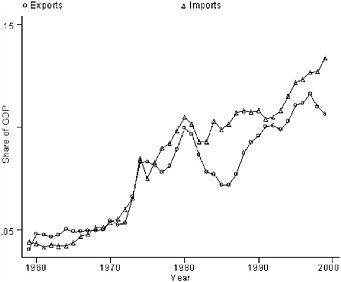

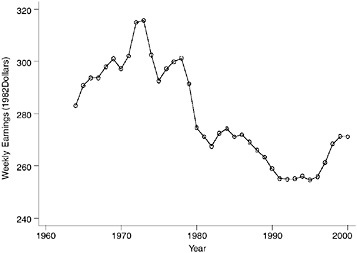

FIGURE 1.2 Share of imports and exports as fraction of GDP.

from the liberalization. There can be sharp distributional impacts of trade liberalization that underlie much of the political tension in the United States and many other countries about trade liberalization. It is not that people do not acknowledge the aggregate gains, but they worry about the distributional impacts and how individual workers will benefit.

The U.S. economy has become much more integrated in the global economy as seen by changes in the flow of trade with other countries. Figure 1.2 shows the import and export share of the gross domestic product (GDP) from the late 1950s to 2000. Imports and exports have gone up over time and, since 1978, imports have exceeded exports as a share of GDP. In the immediate post-World War II period, the United States was basically a closed economy with respect to international trade. Virtually all of the materials that were produced by firms in this country were sold to people in this country. Today, that is much less the case.

Foreign Direct Investment—Flow of Multinational Capital and Technology Across Borders

Labor markets become more global through foreign direct investment (FDI), which occurs when multinational firms set up, expand, and contract operations around the world. Multinational firms and the capital-allocation decisions they make can be important in terms of determining the number of people who choose to be in the labor force. Multinational firms may choose to have expatriates work in other countries. They may also take advantage of particular visa programs, such as H-1B and L1 (intra-company transferees) in the United States, to reallocate labor in their firms across borders.

Multinational firms can be big forces toward greater competitiveness in product markets. Many studies show that,

especially in low- and middle-income countries, entrenched domestic firms face strong competition when multinational corporations come in. There are distributional impacts again, but the competition effects are undeniable. Multinational firms are important when one thinks about flows of capital and technology across borders.

If other firms can make capital decisions across borders, through arm’s-length decisions, why should the focus be on multinational firms? Even in countries that host many multinationals, such as the United States, multinationals constitute only a tiny fraction of all firms.

Consider this snapshot of the United States in 1999, the last year for which there is a comprehensive census of all U.S.-headquartered multinationals. At that time, there were 2,494 U.S.-headquartered multinationals. That is, there were 2,494 U.S.-headquartered firms that had at least one foreign business enterprise in which the firms had a meaningful ownership stake. Examples are IBM, Johnson and Johnson, and other pharmaceutical companies. There were also about 8,600 affiliates of foreign-headquartered multinationals in the United States. These included the U.S. subsidiaries of foreign-headquartered multinationals (for example, in pharmaceuticals and automobiles). According to the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, that year there were 17.4 million non-foreign proprietorships, 1.8 million partnerships, and 4.8 million corporations, totaling about 24 million firms in the country. Therefore, less than one-twentieth of one percent of all U.S. firms were parts of multinationals. Why then should we care about multinationals?

Multinationals matter because they constitute such a large share of many macroeconomic aggregates. In the United States, multinationals account for about 25 percent of all employment, about one-third of the national GDP, about 40 percent of the capital investment, 60 percent of the imports, and 80 percent of the exports. Private-sector R&D is accounted for almost entirely by U.S.-headquartered multinationals and their foreign affiliates. The creation of knowledge and new ideas is basically an activity of multinational firms.

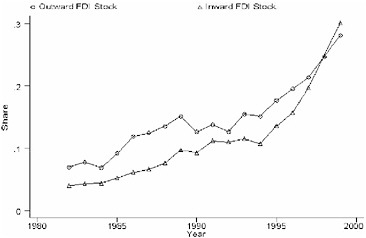

In summary, national labor forces become more global through cross-border flows of people, as well as through trade and FDI. If immigration were shut down, international trade and FDI would be at least as important in determining how wages and earnings are set in countries. Over the last 20-30 years of increased integration around the world, multinational firms have been engaged across borders much more than before. For example, the wave of globalization in the decades before World War I was due primarily to the flow of people across borders. Immigration was massive in those decades. Multinational firms were basically nonexistent. The situation now is almost the complete opposite. In recent decades, cross-border flows of FDI have grown much faster than cross-border flows of goods and services and of people (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 Cross-border flows of FDI stock as fraction of GDP. SOURCE: Scholl (2000, Table 2), Bureau of Economic Analysis.

WHO SHOULD CARE ABOUT GLOBALIZATION OF LABOR FORCES?

Should firms care about this process of globalization? How about workers? The answer depends a lot on what the rest of the world looks like in comparison.

Workers’ Perspective

Wages Around the World

From the standpoint of workers, it is important to look at earnings both inside and outside workers’ own countries. What is going on in other labor markets now has an impact on labor markets in countries such as the United States because of the flows of people, ideas, and technology across borders.

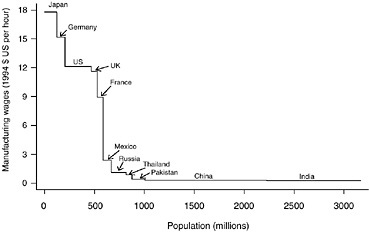

Figure 1.4 shows average manufacturing wages in various countries in 1994. There are some high-wage, low-population countries and some low-wage, massive-population countries. There are more than two billion people in China and India, where hourly wages are about one one-hundredth of the wages in developed countries such as the United States.

Those differences across borders are sustained by natural and political trade barriers, such as policy decisions restricting the flow of people, goods and services, and capital across borders. The differences are also influenced by national differences in skills in capital and technology, which depend on the human capital, physical capital, and knowledge that people are able to bring to the workplace. As globalization occurs, some think wages in countries such as the United States are being driven down to the level of Chinese wages. At the same time, history has shown that countries like the United States have had wage increases even though China, India, and others are low.

FIGURE 1.4 Average manufacturing wages in various countries in 1994. NOTE: According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, hourly pay in manufacturing for 2001 was about $0.61 in China and $16.23 in the United States. According to U.S. Census data for 2002, the population of China was 1,309,380,000 and the population of the United States was 287,676,000.

Skill Sets

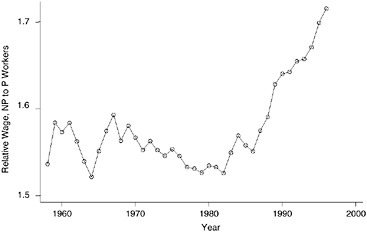

One important distinction between workers in different countries involves the distribution of earnings across skill sets. In the U.S. manufacturing sector, nonproduction workers have a higher level of educational attainment and more experience than do production workers (Figure 1.5). The skill premium, which was about 60 percent in the late 1950s, was actually falling throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s, there were provocative discussions about how too many educated people were coming into the labor force.

FIGURE 1.5 Skill premium in U.S. manufacturing. SOURCE: National Bureau of Economic Research, Manufacturing Industry Database http://www.nber.org/nberces.

Somewhere around 1980, something started to change in the U.S. economy, and the return to skills has been rising dramatically since then. Different slices of the data related to measuring skills yield slightly different pictures, but the overall trend is a fact: The return to skills in the United States has been going up for almost a generation now. Income equality across skills has also gone up dramatically. The same has been true in many other countries.

It could be said that more-skilled workers are doing well because there are fewer of them in the U.S. economy, but the data do not demonstrate that. The relative supply of more-skilled workers in the country has been increasing, not decreasing. Labor economists look at four main groups of skill sets: high-school dropouts, high-school graduates, those with some college education, and college graduates and beyond. In the 1940s, 76 percent of the U.S. labor force were high-school dropouts. Only 5 percent of the U.S. labor force had college degrees or more. During the second half of the twentieth century, the skill mix of the U.S. labor force increased dramatically because of the GI Bill and rising income. By 1999, about 25 percent of people in the U.S. labor force had college degrees or more.

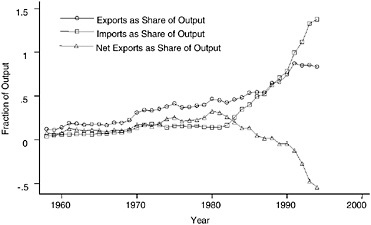

However, absolute earnings adjusted for changes in price inflation have not been rising for everyone. An example of the decline in these earnings is seen in Figure 1.6, for average private-sector, nonfarm weekly earnings adjusted for price inflation. Real earnings in the United States actually peaked in the early 1970s for a large fraction of the labor force—private-sector, nonfarm workers, who make up 85 percent of all United States workers and are the subject of one of the main available data streams. For a long time, their earnings fell; in the second half of the 1990s, there was a turnaround.

FIGURE 1.6 Average private-sector nonfarm weekly earnings. SOURCE: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, nonfarm payroll statistics from the current employment statistics (http://www.bls.gov/datahome.htm).

FIGURE 1.7 Import and export shares of output for computers and office products (standard industrial classification (SIC) 357).

Real earnings of different skill groups have been very different. Real earnings of more-skilled workers have been rising, but earnings of the middle- or less-skilled workers were flat or falling throughout the 1970s and the 1980s and into the 1990s. In the second half of the 1990s, there were increases across all parts of the skill distribution.

Multinational Firms

This increase in real wages since 1995 has been largely driven by global integration of the IT sector. Multilateral trade in the computer and office-products industry (standard industrial classification—SIC—357) was sizable and had a growing surplus with the rest of the world early in the time frame of Figure 1.7. Something started to change in the early 1980s in this industry. Exports continued to grow and imports exploded as a share of GDP. The trade balance in this industry then quickly went to zero and became dramatically negative, continuing this way into 2000. In that year, the industry had a trade deficit with the rest of the world of $30 billion.

However, the IT industries are special. Many studies have documented that in the second half of the 1990s, when there was growth in both productivity and in real income in the United States, they were driven by the IT industries such as computers and office products. These industries became much more productive and, as a result, prices went down substantially and firms and all their associated industries demanded a lot more capital in IT. Some of it was a bubble, but it is clear that these are special industries that overall have driven much of the productivity gains in U.S. real income.

The early personal computers in the 1980s, such as the Apple IIe, were not only produced in the United States, they were produced in one location, such as Silicon Valley. Now production is scattered all over the world. Today, a laptop has probably been made in 15 countries: all the components come from different parts of the world in elaborate global production networks that multinational firms have set up.

If in 1980 the United States had closed its borders and not allowed IT to globalize as it did, there probably would not have been the IT boom enjoyed in the 1990s. The IT industries would not have been able to deliver the productivity gains and price declines that they did.

To summarize, research by economists has concluded that in recent decades globalization appears to have been more beneficial for more-skilled workers in the United States than for less-skilled workers. It also seems that the boom time in real wages since 1995, driven largely by IT, has had a lot to do with globalization. These gains from global integration are widely distributed across skill groups.

WHO WILL BENEFIT IN THE FUTURE FROM GLOBAL INTEGRATION?

Demographic Trends

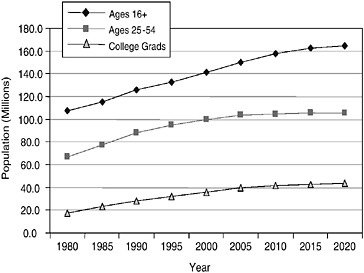

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that the total U.S. labor force went from a little over 100 million in 1980 to about 140 million in 2000 (Figure 1.8). There will be much slower labor force growth between now and 2020 than in the previous generation. Annualized growth rate for the U.S. labor force was about 1.8 percent from 1980 to 2000. Going forward, it is going to be about 0.8 percent per year. These estimates assume that birth rates and death rates remain as expected. The estimates also take immigration into account; the only wild card in the estimates is what is going to be changing in U.S. immigration policy.

FIGURE 1.8 Projected U.S. labor force. SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau.

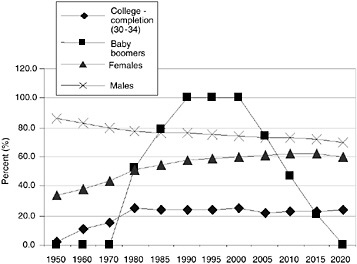

FIGURE 1.9 Projected U.S. labor force participation rates for 25-54 year olds, and for 30-34 year olds who have completed college. SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau.

The prime age segment of the U.S. labor force, those 25-54 years old, is going to be virtually stagnant in the next 20 years. The projected growth is going to be from about 100 million to about 103 million. In other words, the number of prime-age, highly skilled working people is going to be virtually flat, in absolute terms, in the United States in the next 20 years. The number of college graduates is also going to grow more slowly than it did in the past. Thus, the pool of college-educated, prime-working-age people in the U.S. labor force is hardly going to grow in the next 20 years. In the post-September 11 world, it is more likely that there will be a reduction of U.S. immigrants than an increase.

Part of the slowdown in aggregate growth in the labor force is that there are not enough “baby busters” to replace the baby boomers, who are moving into retirement (Figure 1.9). In addition, the fraction of men who choose to be in the labor force has been declining in the U.S. economy for decades and will continue to decline slightly. This had been the opposite in the past. A major change that drove labor force growth in previous decades was the rise in female participation, driven by equal rights movements and changes in family structures. The fraction that is going to choose to be in the labor force is going to be virtually unchanged in the next 20 years.

College completion rates of people 30-34 years old also have influence. More young people are entering college, but the share that gets a degree has stagnated and will continue to do so.

Multinational Firms

For IT and other areas such as pharmaceuticals and chemicals today, there is a concern that more-skilled workers are at risk—and that good jobs are being outsourced and are leaving the United States. Again, multinational firms have been at the forefront of this process. They mediate substantial flows of the technology, capital, and trade of goods and services across borders. General public opinion is that multinationals necessarily cut back on domestic facilities by setting up production offshore. In hardware and increasingly in software, this is a salient discussion right now. Worker advocacy groups and unions are protesting the movement of production overseas. Politicians are claiming that studies are needed. Here in the District of Columbia, there have been hearings about this in Congress. There was an important hearing in the House of Representatives in June 20031 about the outsourcing of U.S. white-collar IT jobs and whether the economy can survive it.

Consider a U.S.-based pharmaceuticals producer. Suppose that in response to a fall in labor costs abroad, it decides to relocate some of its R&D activities to India. What happens to labor demand in the firm’s U.S. operations? There are three possibilities to consider: (1) Substitution effect—labor in the United States and labor in India are substitutes for each other, a decrease in Indian labor costs mean a cutback in the U.S. labor demand. However, it may be that Indian labor and U.S. labor are actually complements, rather than substitutes. (2) Scale effects—lower costs allow the firm to expand its operations in all lines of business and stimulate demand for workers everywhere, including in the United States. (3) Scope effects—the firm may change the mix of what it does; it could change its activities in the United States. The IT industry has been doing this in recent years: even production workers have started to do other things within the company.

The potentially incorrect idea here is that labor in the United States and labor in India are substitutes for each other, a decrease in Indian labor costs mean a cutback in the U.S. labor demand. However, it may be that Indian labor and U.S. labor are actually complements, rather than substitutes. If the people in India are doing work, then perhaps those in the United States will be more productive. The interchange of computer code and other technical results may make people in the United States more valuable and more productive to the firm.. The actual impacts and net effects are much more complicated than might appear to be the case at first glance. It is an oversimplification to focus on only the substitution effects and conclude that the results will be bad. There is more involved.

Evolution of Chemical Multinationals

For each of the measures of capital stock (K), employment (L), and value of R&D, the fraction of the total world-

TABLE 1.1 Global Evolution of Chemical (SIC code 28) Multinationals

|

Year |

Parent K ($ Million) |

Parent L (Thousands) |

Parent R&D ($ Million) |

Affiliate K ($ Million) |

Affiliate L (Thousands) |

Affiliate R&D ($ Million) |

|

1982 |

73,321 |

1,365 |

6,864 |

15,362 |

668 |

658 |

|

Fraction (%) |

82.7 |

67.1 |

91.3 |

17.3 |

32.9 |

8.7 |

|

1989 |

92,149 |

1,255 |

12,444 |

25,661 |

475 |

1,912 |

|

Fraction (%) |

78.2 |

72.6 |

86.7 |

21.8 |

27.4 |

13.3 |

|

1999 |

133,513 |

902 |

27,400 |

59,572 |

532 |

4,221 |

|

Fraction (%) |

69.1 |

62.9 |

86.7 |

30.9 |

37.1 |

13.3 |

wide amount done in the U.S. (parent) and in abroad (affiliate) has been determined (see Table 1.1). In 1982, 82.7 percent of the global capital stock of chemical (SIC code 28) U.S.-headquartered multinationals was in the United States. The fraction of capital that is outside the United States increased from 17 percent in 1982 to 31 percent in 1999. The affiliate labor force has increased, with a dip in the 1980s and a dramatic increase in the 1990s. There was a big increase in R&D in the 1980s, but it reached a plateau over the 1990s. In an absolute sense, R&D done abroad has gone up considerably from $1.9 billion to $4.2 billion, but there has been a similarly dramatic increase in the amount done in the United States as well. The overall message is that U.S.-headquartered chemical multinationals are becoming more global in where they are choosing to operate. Whether foreign R&D workers in chemicals are substitutes for or complements to those in the United States is yet to be determined.

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF GLOBALIZATION

It is important to keep in mind that a large number of Americans oppose freer trade, immigration, and FDI. However, these preferences tend to cleave strongly across labor-market skills: less-skilled Americans are much more likely to oppose liberalization. This may be the result of labor-market pressures across skill groups. As mentioned previously, less-skilled Americans have not done very well in the U.S. labor force since the early 1970s. If pressures switch towards the more-skilled workers in the future, perhaps the support for globalization will wane.

Unless there is a dramatic policy shift away from global integration; however, flows of goods and services and capital will continue to be more of an influence than the flow of people. The choice to become global has been expanding for firms, including chemical firms, which are increasingly able to take advantage of the situation especially with declines in communication costs. For workers, the direct impact is less certain and will depend at some basic level on how workers in the chemical industries in the United States compare with workers in other countries. In turn, that comparison is going to feed into the substitution, scale, and scope issues that determine what is going to happen to the demand for firms, universities, and workers in the United States. In the longer term, the evolution of the U.S. labor force is going to depend considerably on the skills that national education systems impart, which may be affected by immigration policy and the preparation of students.

REFERENCES

Borjas, G. J., R. B. Freeman, and L. F. Katz. 1997. How Much Do Immigration and Trade Affect Labor Market Outcomes? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 0(1): p. 1-67.

Saxenian, AnnaLee. 2002. Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant High-Growth Entrepreneurs. Economic Development Quarterly. Vol. 16 (1). p. 20-31. February 2002.

Scheve, Kennth E., and M. J. Slaughter. 2001. Globalization and the Perceptions of American Workers. Washington, D.C.: Institute of International Economics.

Scholl, Russell B. 2000. The International Investment Position of the United States at Year End 1999. Survey of Current Business 80 (July 2000): 46–56 Bureau of Economic Analysis.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2003. Migration of Natives and the Foreign Born: 1995 to 2000. Census 2000 Special Reports (CENSR-11).

DISCUSSION

Matthew Slaughter’s economic perspective of globalization provided a background for the remainder of the workshop. As the first presentation it generated many questions on such topics as the international constituency of science and technology workers and the policy goal of education. Global competition in R&D was discussed.

Foreign Labor Force

Donald Burland, of the National Science Foundation, noted the high percentage of non-U.S. workers making up the labor force of new R&D facilities being opened in other countries and in the similar high percentage among the graduate students and postdoctoral students in U.S. chemistry departments today. He asked what the impact of this might be as production moves overseas.

Slaughter responded that there is always a question for

R&D-intensive industries about how close the R&D workers should be to the production. The answer depends on what industry or company it is. Some companies are easily able to separate R&D and production geographically. IT hardware is an example. Much of the IT R&D has remained in developed countries like the United States, while production is all over the world. To the extent that production and R&D need to be closer together for working out problems in the production process and for more interfaces between initial manufacturing and testing, R&D may follow production. If foreign students who are getting their education in the United States are not allowed to stay and work in this country, much of the R&D and production may move with the students.

Good profit-maximizing firms try to segment markets in terms of money. For instance, it has made sense for pharmaceutical firms to charge much higher product prices in high-income countries such as the United States than in low-income countries. It is pretty clear that policy in the United States and in other countries will change that business model radically in coming years. One needs to think about how the policy change is going to feed back into knowledge creation, investment, and production.

The political and natural physical barriers that have been in many chemical and pharmaceutical industries are being destroyed by flows of information and by policy choices. That is going to have a big impact on what these companies decide to do.

Ratio of Wages of Nonproduction to Production Workers

Alvin Kwiram, of the University of Washington, requested clarification or expansion of the nonproduction-to-production worker ratio of wages discussed earlier. If the Microsoft effect2 is removed from the curve of stock options in many high-technology companies in the 1990s, what would happen to that curve in Figure 1.5?

Slaughter replied that further measures of skills, such as occupation or educational attainment, can be plotted for 1980-2000 and the same picture is obtained. Rising income inequality across skill groups is robust to measurement. The magnitudes will vary, but the general pattern does not.

For 2000-2003, there has been a bit more measurement sensitivity; on some measurements, the magnitude of income inequality has stabilized in the last few years, whereas on others, it has continued to increase. That there has been no dramatic reversal is not surprising. Recessions tend to hit less-skilled workers harder. Unemployment rates are measures of the business cycle, and the unemployment rate for college graduates is still about 3.2 percent. The unemployment rate for high-school dropouts is about 9 percent. The increase in aggregate unemployment that has been seen in the last few years has fallen almost entirely on the less-skilled workers.

Policy Goal of Education

James Martin, of North Carolina State University, was struck by the interesting parallel between the discussion of the economy and his thinking about education and training. There was a clear distinction between thinking about the economy from the macro economy and local economy perspectives. The impact of globalization clearly will depend on the perspective. The parallel with education that he saw was that if what is best for the advancement of science and learning in chemistry were articulated, there would be a very different educational course for land-grant institutions that are mandated to educate the local populace. He asked what should be done for training and educating chemists.

Matthew Slaughter believes that the answer depends on the goals. One option would be to aim to raise average earnings and not be concerned with distributional impacts. At land-grant institutions, an increase in the number of students educated may help those universities because more ideas can be generated.

Some may argue that gains are not achieved by adding more people but by having a few great people. Bill Gates and Bill Georges from Medtronic are examples of people that have stimulated much of the aggregate economic impact. In that sense, the focus of the educational system should be on the “superstars,” and resources should be channeled into honors programs.

The right track is not known, so it is necessary to try to allocate enough resources to both.

Competition in Research and Development

Douglas Selman, of Exxon-Mobil Chemical, thought that increasing competition, in R&D for example, should also be included in the list of major factors in the globalization of the labor force.

Slaughter responded that not only do multinational firms do the majority of the world’s R&D, but the majority traditionally has occurred in a very small number of countries. Scientists in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Germany combined do about 85 percent of the world’s R&D. Improvements in living standards have been attained from technological advances, and for a long time, these ideas have come from a very small number of geographical locations, concentrated in developed countries.

How do these ideas get from those five countries to the other roughly 195 countries? India and China are obtaining more technology and more skills, because of the availabilities of a workforce capable of R&D. India and China have meaningfully entered the world’s economy only in the last five or ten years, so competition is beginning to change.

The U.S.-headquartered multinationals’ fraction of affiliate R&D went from 6.5 percent in 1982 to about 13 percent in 1999. This is similar to the trend observed for chemicals (SIC 28). Slaughter predicted that in 2009, the fraction would be up at 20 percent. Looking to 2019, he predicted it would be 35 percent.

How will these numbers affect the United States? The assumption may be that if there is a fixed pool of R&D and if more of it is being done outside the United States, the result will be bad for U.S. R&D workers, which may or may not be true, depending on how U.S. R&D workers are performing. Productivity will probably increase because Americans can complement the work of foreign academics and research assistants. Activities that used to be very high skilled become less skilled over time (e.g., due to technological advances). Perhaps the R&D workers whose jobs were moved overseas are better off moving to something more advanced.

Selman asked whether there is an opportunity to increase the level of U.S. R&D or technology capability to remain on the leading edge. He has noticed that the U.S. competitive edge in science and technology development may be eroding due to rapidly increasing capability in other countries. However, he said the advantage we can possibly sustain longer is our ability to develop commercial application of new science and technology. It appears that it is easier for other countries to develop strong science programs in their universities and government labs than it is for them to master the complex interface between science/technology and business opportunities required to commercial new technology (i.e., innovation).

Slaughter commented that the United States still maintains a big advantage over many of other countries in allowing new ideas and new processes to get out of the laboratory and into the marketplace. In 1994, no one foresaw the impact of the Internet, which was able to commercialize dramatically. It is important that the right business, legal, and educational systems be in place so that fresh ideas can be translated into good jobs at good wages.

Global Universities

Christos Georgakis, of Polytechnic University in New York, cited the recent examples of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of Michigan establishing links with Singapore. He asked how Slaughter analyzed the driving force of such partnerships and whether more global interactions among universities will begin to take place.

Slaughter responded that educational labor markets are among the most global and that there will be more of these kinds of interactions. He offered two observations. The faculty at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth is approximately 20 to 25 percent foreign nationals, and he said it is probably similar in other departments and schools. That mode of globalization is flow of people. Educational output is a lot more productive as a result of international collaboration.

The second observation was that educational global engagement and global competition spur innovation. IT is the one industry in the 1990s that had world liberalization of trade and elimination of all tariffs, specifically, the IT agreement of the World Trade Organization. Brazil did not sign the agreement. It is a middle-income country that thought the best way to develop IT was to protect its firms with big tariffs and big quotas on imports. By many measures, the Brazilian computer industry is not very good. The middle-and low-income countries that succeeded in IT were the ones that allowed multinationals to come in, to bring the ideas, and to get production networks integrated.