8

Licensing Decisions and Strategies

8.1 INTRODUCTION

Drawing on the analyses from the preceding three chapters, this chapter presents a menu of options that government may use to decide whether and how to license geographic data and services from and to the private sector. For cases in which licensing is appropriate, the chapter addresses ways to make licensing a more versatile tool, and explores license-based approaches that might satisfy the broadest range of stakeholders.1 There is no intent by the committee through the presentation of this material to convey explicitly or implicitly a general preference for or against acquisition of geographic data and services through licensing.

The chapter begins by presenting a framework for, and issues to consider in, determining whether licensing may be appropriate in specific instances. We then propose strategies that agencies can use when acquiring or distributing data under license. These strategies can be implemented immediately (we discuss longer term strategies in Chapter 9). We focus primarily on the case in which government licenses data from private vendors. However, Section 8.4.3 examines the opposite case of the agency as licensor.

|

1 |

Item 4 of the committee’s task. Chapter 9 also addresses aspects of this task. |

8.2 A FRAMEWORK FOR AGENCY DECISION MAKING

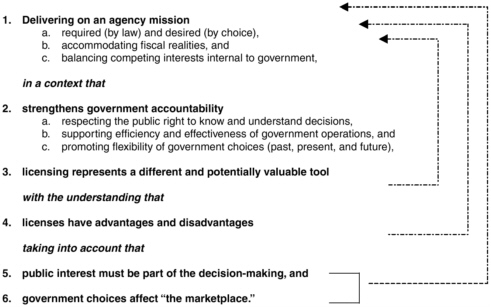

When acquiring or distributing geographic data, agencies must make choices about the most effective and efficient way to accomplish their missions, weighing such factors as data cost, quality, and fitness for use. In making these choices, agencies need to be clear about (1) what the data are initially needed for and (2) what follow-on applications are required or desirable, including both discretionary and nondiscretionary applications. A number of considerations affect the decision-making context for agencies. These can be conveniently presented as a series of iterative steps (Figure 8-1).

FIGURE 8-1 Steps in the decision-making process for geographic data acquisition and distribution. Arrows indicate points in the decision process when it is valuable to revisit earlier components of the decision sequence.

As indicated in Figure 8-1, licensing represents a new and potentially valuable tool for accomplishing agency missions. Like any powerful tool, licenses have both advantages and disadvantages. Before deciding for or against licensing, government decision makers should have a clear understanding of how a decision to license is likely to affect the goals of

efficient and accountable government, the broader public interest, and the probable impact on private markets.

8.3 GOVERNMENT’S MISSION: CLARIFYING AND ACHIEVING THE GOALS

Like most contracts, the structure of a license is a matter of negotiation between license holders and licensees.

Recommendation: Before entering into data acquisition negotiations, agencies should confirm the extent of data redistribution required by their mandates and missions, government information policies, needs across government, and the public interest.

In this section, we suggest rules of thumb that agencies can use to refine geographic data acquisition decisions in support of their mandates and missions. We begin by describing how government could decide which data to acquire and conclude by asking when acquired data should be redistributed.

8.3.1 The Procurement Mission: When Should Agencies Choose Licensing?

Traditionally, the federal government’s preferred procurement method has been to acquire geographic data unencumbered by restrictions on use or reuse.2 However, depending on the circumstances, the advantages of licensing may outweigh the social and economic drawbacks of acquiring restricted geographic data. Because beneficial downstream uses and the public’s interest in the free flow of information cannot be fully anticipated, agencies should exercise caution in construing their mandates and missions to permit licenses that restrict such uses.

Agencies need data to support a wide variety of mandates and missions.3 For this reason, there is no simple answer to the question of when agencies should choose to acquire geographic data through restrictive licenses. Licenses can be made to work in most cases in which geographic data are needed; the challenge lies in determining when licensing data subject to use restrictions is superior to in-house production, purchase of unencumbered data, or acquisition through grants, prizes, cooperative research and development agreements (CRADAs), partnerships, or other alternative methods.

One logical starting point is to identify the method that achieves agency missions at the greatest excess of benefits over costs.4 Licensing may or may not be this method. The following four examples illustrate some advantages and disadvantages of licensing.

-

Time-Sensitive First Response. As discussed in Chapter 4, Section 4.2.5.1, licensing data from the private sector can sometimes result in substantial benefits at minimal direct cost. For example, Palm Beach County, Florida, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) both used licensing to acquire data more quickly than they otherwise could have.

-

Transaction Costs of Licensing Relative to the Value of the Data. Licensing may have significant limitations in some circumstances, particularly for small-scale projects in which transaction costs for negotiating and administering contracts may be prohibitively expensive in light of the size of the overall project.5 In these

-

circumstances, outright data acquisition is often preferable to license-based solutions since the need to negotiate and then administer the license over the life of the data may create high transaction costs.

-

Regulatory Data. In cases in which public data are used to develop and implement regulations, affected parties and the general public have a strong interest in gaining access to whatever data are needed to validate and/or appeal agency actions. Licensing data from the private sector subject to restrictions on downstream access or use may have limited value in this regard.

-

Operational Data. Governments may use data to support such functions as dispatching maintenance staff or inspectors, automatically tracking vehicle location, or managing mobile assets. Such functions may have little policy or regulatory impact. Consequently, government acquisition of commercially licensed data that allows the public and news agencies to view but not acquire data may be a viable alternative. However, citizens may be interested in learning or need to know the details of a specific operational situation (e.g., the dispatching events on September 11, 2001) in order to understand how the policies and operations of government affect its ability to perform.

Recommendation: Agencies should experiment with a wide variety of data procurement methods in order to maximize the excess of benefits over costs.

8.3.2 The Dissemination Mission: When Should Government Acquire Unrestricted Data?

This section provides guidance to agencies deciding when to acquire geographic data with no restrictions on reuse and distribution.

The first consideration is whether the data have regulatory or policy consequences and should therefore be available for redistribution subject to few or no restrictions (Section 8.3.2.1). If this is not the case, then the decision depends on whether the data are for internal use only (Section 8.3.2.2), are to be widely distributed at marginal cost (Section 8.3.3.3), or are being acquired for limited redistribution (Section 8.3.3.4). Most opportunities for creative licensing solutions lie in this last-mentioned category of limited redistribution.

The main determinant of whether an agency should acquire geographic data subject to restrictions on reuse or redistribution is the agency’s interpretation of its mandates and missions. Factors that agencies should take into account when exercising discretion are discussed later.

8.3.2.1 Data of Regulatory or Policy Importance

When government uses geographic data to promulgate regulations, formulate policy, or take other actions that affect the rights and obligations of citizens, there is a compelling interest in making these data available so that the public may understand, support, or challenge government decisions.6 This interest often will be served by acquiring unlimited rights in data, but also may be accommodated in some circumstances by licensing data under conditions that permit access for more limited purposes. For example, in some cases, the public may need access only to views derived from satellite data, rather than the underlying data themselves. The important principle is that access to information cannot be so limited, its distribution so difficult, or its content so closely held by government that outcomes of political debates are determined by unequal access to data.

8.3.2.2 Internal Use

When geographic data are used for purely operational tasks (e.g., emergency dispatch, project management–style resource allocation, traffic management, military operations), distribution may not be necessary. When such circumstances do arise, the agency is like a private business—it should adopt licensing solutions if they are more cost-effective than the alternatives.

8.3.2.3 Economic Factors Supporting Broad Distribution of Government Data

7There are circumstances when providing access to the public at no more than the marginal cost of distribution is appropriate from an economic perspective and others when it is not. Before deciding to accept licensed data subject to some level of reuse restrictions, agencies will need to assess the potential value of the data to secondary and tertiary users against the additional costs of obtaining unrestricted rights. Because the benefits of secondary and tertiary uses may be difficult to quantify, agencies should guard against the temptation to accede to reuse restrictions too readily. Conversely, there is also a danger that government may avoid licensing data for historical or institutional reasons even when it would be rational to do so.

Unfettered public access may be more appropriate where certain fact patterns are present. Although the following guidelines are not intended to be all-inclusive, access at no more than the marginal cost of distribution may be appropriate when

-

There is broad consensus that the resource is needed. Unfettered access to government data is most fitting when there is little or no uncertainty that a particular resource is needed. The best evidence of consensus is a legislative or an administrative mandate specifying the need for the data among broad segments of society in support of social or economic objectives. Under these circumstances, the information has already been deemed of value for society through the legislative process.

-

The data are used for public research. Often, government data are used in basic and targeted research both inside and outside the government to support public purposes. A government agency should obtain broad rights for public dissemination when the geographic data it acquires are likely to be useful in follow-on research and development activities.8 When the broad public benefits of research are clear, it is appropriate for government data to be used for those purposes and, as such, to be provided at

|

7 |

The term open access is sometimes used in this context. See definitions in Chapter 1, Section 1.4. |

|

8 |

Even in these cases, however, the government may not wish to purchase the data outright, so that the licensor still may be able to sell products derived from the data to others in the private sector. |

-

the marginal cost of distribution. The quid pro quo should be that the results of the research also should be part of the public domain.

-

The data cannot be obtained by other means. In rare cases, market failures produce a shortage of geographic data. Examples include, but are not limited to, (1) inability to obtain capital for exceptionally large or risky ventures, (2) low legal or technical barriers to copying, and (3) inability to persuade large numbers of dispersed actors to share information and resources.9 Thus, for example, it may be appropriate for a government agency to acquire broad rights when the risks of developing geographic data are large and the government must guarantee substantial spending in order to induce investment. We stress that such market failures are uncommon and should not be presumed without clear and convincing evidence of the broader public, not private, interest. The cost-benefit calculus in these circumstances will be difficult, and is complicated by the need to assess how benefits will be shared. Government should be loathe to fund investments that result in private monopolies or oligopolies.10

-

The data are required as "infrastructure" upon which other datasets or data products rely. Some geographic data supply the “infrastructure” needed to allow the integration of data among federal, state, and local agencies or to spawn new commercial products. In such cases, it may be appropriate for the government to acquire broad redistribution rights. A previous National Research Council report has suggested, for example, that environmental data should follow a “tree” model in which a government-funded

|

9 |

Currently, there are indeed low technical barriers to copying geographic data, and the geographic data community has yet to develop the infrastructure and incentives that would allow efficient and effective sharing and exchange of geographic data among large numbers of dispersed actors (see Chapter 9, Section 9.3, for potential approaches for addressing these issues). However, it is difficult to argue that these low technical barriers and the less-than-optimal exchange infrastructure are so severe as to be causing shortages of geographic data in the United States. |

|

10 |

Oligopoly is a form of imperfect competition in which there are relatively few firms, each of which must take into account the reactions of its rivals to its own behavior (adapted from W.W. Norton and Co., 2003, Glossary, available at <http://www.wwnorton.com/college/econ/stiglitz/gloss.htm>). |

-

trunk supports lush commercial branches.11 Comparative studies show that the U.S. government’s open information policies have contributed significantly to the U.S. information industry.12 Federal government policy should continue to prevent agencies from claiming any proprietary interest in data and should continue to provide unrestricted access to public information by the commercial sector and others.

The foregoing considerations are subject to three caveats or conditions:

-

Public provision should take place at the lowest government level that includes all potential users. To avoid taxing one group of citizens to benefit another, geographic data should be provided by the lowest level of government that embraces all potential users.13 For very small groups, government may not be needed at all. Instead, agencies might encourage those outside of government to pool their resources and control free riding by entering into intragroup contracts and organizations.

-

Government should not make technical choices in anticipation of secondary and tertiary uses. Technical specifications for government data should be based on the needs of the procuring agency and its participating stakeholders.14 Government does not have sufficient information to choose the best solution for complex technical problems that are outside its domain. Privately held information about potential downstream uses of government data in the marketplace is best elicited and supplied by the private commercial sector.

-

Government should not try to anticipate consumer preferences. Government should procure data that meet its existing needs and those of its stakeholders as defined by its mandates and missions. It is difficult and often counterproductive to anticipate the number

|

11 |

NRC, 2001, Resolving Conflicts Arising from the Privatization of Environmental Data, Washington, D.C., National Academies Press. |

|

12 |

See Chapter 4, Section 4.3. |

|

13 |

As noted in Chapter 6, however, it must be recognized that it may be difficult to apply this principle when, as is often the case, the potential beneficiaries cannot be identified in advance. |

|

14 |

It is entirely appropriate for an agency to develop technical specifications with its collaborators, partners, and known stakeholders. |

-

of users and all the potential uses of a proposed dataset. Historically, government has done a poor job of determining what markets need (e.g., the Landsat program).

The foregoing considerations and caveats are offered as an aid in assessing whether to acquire data so that they may be made available to the public at or below the marginal cost of distribution. No one factor is intended to be dispositive. When multiple factors collide to generate “warning flags,” alternative procurement options for acquiring geographic data should be carefully evaluated before going forward. Figure 8-1 suggests a broader framework and policy considerations for conducting this evaluation.

Recommendation: When geographic data are to be used to design or administer regulatory schemes or formulate policy, affect the rights and obligations of citizens, or have likely value for the broader society as indicated by a legislative or regulatory mandate, the agency should evaluate whether the data should be acquired under terms that permit unlimited public access or whether more limited access may suffice to support the agency’s mandates and missions and the agency’s actions in judicial or other review.

8.3.2.4 Limited Redistribution: The Middle Ground

When should agencies accept “reasonable” limitations on their ability to use and redistribute geographic data licensed from the private sector? Compared to other procurement methods, the costs and benefits of licensing tend to be complex. The importance of particular terms usually depends on context. Thus, there is no “golden rule” for determining which license restrictions are appropriate. That said, agencies usually need to weigh such terms as price, dissemination restrictions, available uplift rights,15 and liability.

Recommendation: Agencies should agree to license restrictions only when doing so is consistent with their mandates, missions, and the user groups they serve.

In some cases, potential user groups are sufficiently small for direct consultation. For example, university libraries routinely decide whether to accept particular licensing restrictions by talking to the faculty and students who are likely to use the resource. Some professors may not care if a particular license lets them reprint satellite images from an electronic journal. For others, the data may be useless without these rights. Ideally, library staff do not make such judgments; instead, they consult the affected parties directly.

Determining “reasonable” restrictions becomes harder as the number of potential users grows or is not known in advance. Researchers frequently use government data and databases to advance science. Many commercial firms use government data as a source of raw material for creating value-added industries. Citizens, educators, and scholars may derive substantial educational benefits or use government’s data to check on potential abuses by government agents. These numerous other beneficiaries of government datasets will not be directly represented in licensing negotiations. Therefore, when an agency’s mandates and missions specify consideration of such uses, an agency will need to consider the needs of such constituencies before licensing data subject to reuse restrictions. The needs of parties external to an agency’s mandates and missions may be accommodated through government’s broad information policies as specified by its laws.

As the number of potential users grows, agencies must increasingly rely on sampling to discover whether proposed restrictions are acceptable. Here, the challenge is to create an open and transparent approach that accurately conveys the user community’s wishes. Many uses and users of government information are unexpected and are not likely to be identified in advance. Such needs are unlikely to be accommodated by government agents that acquire licensed data for a specific government purpose. Nonetheless, if a government agent can identify at least some government users and survey their needs, negotiations can become more informed.

Large and diverse user groups add further complications. This is because data with multiple uses typically have sharply different value for different users. Absent effective price discrimination, imposition of licensing restrictions by private firms normally will exclude at least some customers from the market. Furthermore, the number of remaining customers may not be enough to sustain the activity. Government provision may be appropriate in these circumstances.

Finally, the appropriateness of restrictions may be influenced by the nature of the content disseminated. If government users only require

visualizations of datasets, rather than access to the underlying data,16 some form of licensing restriction on the use of the underlying data may be appropriate. Conversely, license restrictions may be inappropriate when the underlying data are widely distributed and used among the government users. In this case, the data are likely to constitute part of the “public record” on which government decisions are based. If the data constitute a public record, the public must have access. Licenses that provide open access to the public, yet restrict the public from using these data in further products or ban further dissemination, may be appropriate under some circumstances.

Recommendation: Agencies that acquire data for redistribution should take affirmative steps to learn the needs and preferences of groups that are the intended beneficiaries of the data as defined by the mandates and missions of the agency. Agencies should avoid making technical choices in anticipation of secondary and tertiary uses or consumer preferences.

8.4 LICENSING STRATEGIES

When an agency decides to license data from the private sector, creative license design can make the difference between success and failure. This section provides a menu of licensing models for agencies to consider when licensing privately owned data and discusses strategies for government licensing of data to other groups.

8.4.1 Designing Licenses in the Public Interest

Having decided what mission goals a license needs to accomplish, agencies must select the right tool for the job. Agencies often face a tradeoff between cost and restrictions.

8.4.1.1 Price

If agencies can accomplish their mission at lower cost with greater benefits by resorting to, say, outright acquisition through an acquisition-

|

16 |

See Chapter 3, Section 3.8. |

for-hire arrangement or through in-house collection, they will do so.17 Private data producers know this and realize that they must set license prices accordingly—even if it means, in the short run, licensing data at a loss. For this reason, an agency’s ability to acquire data outright provides an effective “cap” on licensed data prices.

The price of licensed data typically is entangled with restrictions on redistribution, uses, or other license terms. In the interests of simplicity, this subsection focuses on pricing strategies that are more or less uncoupled from those issues.

-

Bulk Purchases. Data providers are almost always willing to reduce prices to customers who promise to purchase large volumes of data. For example, the National Geospatial-intelligence Agency’s (NGA’s) recent Clearview Agreement cut the federal government’s per-unit satellite image costs by roughly 75 percent.18 The desirability of such arrangements depends on the agency’s needs.19

-

High and Predictable Needs. If the agency knows that it will have to make bulk purchases in any case, per-unit discounts are normally desirable and available. However, the duration and size of these bulk purchases requires careful judgment. On the one hand, agencies usually can obtain deep discounts by agreeing to large, multiyear contracts. On the other, such contracts can (1) reduce competition between vendors over the time frame of a particular contract and (2) lock in high prices in a falling market.20

-

Furthermore, budget uncertainties and electoral cycles can make it difficult for agencies to commit to multiyear contracts. The Nextview contract between Digital Globe and NGA is a case in point. This multiyear contract has a spending ceiling of $500 million, but it contains no spending guarantees beyond the current budget year.

-

High and Unpredictable Needs. Agencies can find it hard to predict future need. For them, bulk-purchase contracts trade increased risk of changing needs or dropping prices for a shortterm price reduction. Such trades may be sensible when vendors are willing to offer significantly lower prices. However, there is the temptation to claim credit for a highly visible price concession while downplaying the associated risk.

-

Limited Needs. Agencies with low individual needs have a powerful incentive to band together. Indeed, some agencies collaborate because their needs are not unique enough or critical enough to justify the cost of acting independently. Various coordination strategies exist, including uplift fees, consortia, and lead agency agreements. Agency interest in better coordination within and between different levels of government is apparent from recent federal initiatives such as Geospatial One-Stop, The National Map, MAF/TIGER (Master Address File/Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing system) modernization, and the civil agency response to the U.S. Commercial Remote Sensing Policy.

8.4.1.2 Nonmonetary Factors

Over the past year, several data vendors (e.g., Space Imaging, Digital Globe, SPOT) have renewed their emphasis on long-term, bulk-sales agreements. Such risk management is particularly important to satellite data vendors, who face high fixed costs and an uncertain market. Government agencies also are interested in minimizing the risk of changing circumstances. Agencies can use the following techniques to manage risk effectively.

|

|

accepted. However, the technology is improving and represents a massive potential retooling in the industry, hence the risk of multiyear contracts. |

-

Noncash Assets. Agencies may find noncash assets that they can bring to license negotiations to lower upfront costs or manage risks. For example, local governments often trade government data for access to private data. Provided that such data trades do not interfere with government’s dissemination mission, the practice may be commendable.

-

Pooled Resources. Agencies and private companies often pool their resources to fund projects that neither could accomplish separately. Joint development projects and CRADAs are usually acceptable to both parties when the private partner agrees to dedicate any discoveries to the public domain. However, private partners may demand restrictive licensing terms for their discoveries or products. In this case, it may be hard to determine whether the benefits of research outweigh the “deadweight loss” associated with these terms. The negotiation may become even more difficult if the private partner agrees to share royalties with the agency. Under these circumstances, the agency may become more interested in maximizing revenues than distributing the resource at a price that encourages widespread dissemination. A preferable alternative may be for agencies to decline offers to share royalties in return for more liberal use or dissemination rights.

-

Data Certification. Some vendors view government certification as a potential selling point.21 In principle, agencies that invest the time and effort to provide such certification could demand a fee or discount in exchange. However, there is a sharp distinction between mandatory and voluntary government certification. Given the sophistication of most consumers, a mandatory requirement that private companies use only data certified by government (e.g., as a requirement for federal funding) could be perceived as an unreasonable infringement on consumer sovereignty. Voluntary certification would be fundamentally different because it offers consumers additional information (i.e., data screening by a trusted agency) without limiting their ability to choose uncertified products. However, certification by government that the data are accurate, complete, or fit for a particular purpose may raise liability concerns for government.

-

Network Externalities. Information markets are said to exhibit “network externalities” in which otherwise identical goods become more valuable if they share a common standard. In the geospatial community, commercial products gain value by being compatible with government maps and digital geographic data. In recent years, local governments and commercial mapmakers and data providers have donated data to federal agencies (e.g., the U.S. Census Bureau and FEMA) to keep their products compatible. In these circumstances, the government obtained valuable data at a low or zero cost.

8.4.2 Restrictions on Dissemination

Vendors may offer federal agencies deep discounts compared to other consumers. Often, such “price discrimination” is acceptable and may even promote public policy. However, price discrimination can rarely be implemented without restricting the agency’s ability to disseminate the data to secondary and tertiary users. Whether such restrictions are appropriate depends on the facts of each case. In some cases, price discrimination can be accomplished without any restrictions. In other cases, stringent restrictions may be required.

8.4.2.1 Making Licensing Choices

When agencies contemplate acquiring data with limited redissemination rights, they should ask their agency users and other likely government users which restrictions will eliminate their ability to use the data for intended purposes, which restrictions they can live with, and to what degree they are willing to make price tradeoffs. When users are relatively homogeneous, bright-line restrictions22 offer the greatest potential for predictable outcomes. Examples include fixed update and embargo periods, blanket permission to publish isolated images or other data in academic journals, and numerical restrictions on resolution. These examples are all cases in which the benefits of licensing may exceed the costs.

Bright-line restrictions become progressively less useful as the group of users that is covered by a license becomes larger and more diverse. Controversy often centers on users’ rights to create and distribute derivative products. Most commercial satellite companies have adopted a bright-line solution that allows licensees to create and distribute any derivative product that cannot be inverted to recover the original data. Although this approach may not be practical with all other forms of geographic data and the derivative products created from them, there are instances in which this approach might be used productively with other forms of geographic imagery, such as with photogrammetric imagery.

As in any negotiation, vendors typically ask for more restrictions than their bottom line requires. For this reason, agencies should be willing to engage in negotiation. Agencies should be particularly careful not to accept restrictions unless they serve a clear and articulated business function of the vendor. For example, “best-efforts” clauses should be approached with caution.23 On the one hand, vendors probably assign little value to such assurances; on the other, agencies are already reluctant to exercise ambiguous contract rights. Best-efforts clauses will only exacerbate this problem.

8.4.2.2 Purchasing Adequate Uplift Rights

Uplift provisions in a license allow future acquisitions by specified parties under specified terms and conditions without the need to negotiate a new license. Often, the additional parties are other government agencies. However, the government also might consider acquiring such rights in order to permit public access to the data. Agencies seldom if ever negotiate uplift rights for individual members of the public. Yet, agencies sometimes perform geographic information system (GIS) services for individual consumers on an on-demand basis. Uplift rights could be a cost-effective way to serve the relatively small number of citizens that make such requests. In many cases, agencies may be able to estimate the amount of data the public will request even though they do not know which individuals will make requests. In this case, it might be useful to prepay for the right to distribute limited quantities of data, unless the number of expected requesters or other factors weigh in favor of purchasing the data.

Redistribution rights also can be made contingent on future events. Disaster assistance is one example, and a clear list of permitted uses is important under these circumstances.24 In principle, the ex ante price of disaster assistance data should be smaller than the ex post price, when agencies usually are prepared to pay a premium for timely information. In practice, the effect is usually small; most data vendors respond to civic demands and are supportive in emergencies.

These considerations must be weighed against the added cost of obtaining such rights in the first place. Like any other option, uplift rights add to the cost of the agency’s original contract. In general, uplift rights probably do not make sense for small data procurements that are unlikely to be requested a second time.

Nevertheless, uplift rights may be underused. Negotiators who obtain uplift rights must pay higher prices and incur additional negotiating expense. When the rights are exercised, however, benefits may flow to other agencies. Well-designed uplift rights remedy this problem by providing discounts or rebates to the original agency if and when the rights are executed.

8.4.2.3 Are Restrictions Necessary?

Restrictions on reuse and redistribution are not necessary in some markets. Such markets are usually “thin” in the sense that customers have little chance of organizing an aftermarket in the vendor’s data. This is common with aerial photography, where customers traditionally have received unlimited use and redistribution rights through professional data acquisition services contracts.25 In theory, such arrangements should act as a brake on the vendor’s ability to resell the data a second time. In practice, the effect is negligible. The October 1998 version of Canada’s Radarsat form contract26 provided an example of this phenomenon. It authorized licensees to create and redistribute any value-added product, including those that could be inverted to recover the original dataset. Because users had to invest substantial resources to create derivative

|

24 |

See, for example, USGS Policy 01-NMD001 (April 2001): “Whenever possible, agreements should also allow the unrestricted use of such data for disaster response, research, or educational purposes.” |

|

25 |

Paper maps are another example of a product that is seldom, if ever, licensed, even though they may be copyrighted. In this instance, copyright and high copying costs provide an effective business model. |

|

26 |

See Chapter 4, Section 4.3. |

products in the first place, the model still provided important barriers against free riding. In effect, the licensor made a practical judgment that it could tolerate whatever “leakage” occurred. The deeper message is that contract drafters should pay more attention to what customers will do than to what they might do. The fact that data vendors seldom enforce existing contract terms27 suggests that the earlier Radarsat-type provisions may be feasible in some other contexts.28

The need for use and redistribution restrictions is also reduced by large data acquisitions. In particular, such agreements (1) reduce exposure to leakage by reducing the size of any remaining market, (2) limit the risk that a vendor will lose its investment, and (3) increase the probability of leakage no matter what contract is agreed. Similarly, time-sensitive geographic data may not need use and dissemination restrictions beyond the initial embargo period, since only the up-to-date data have commercial value. Under these circumstances, vendors can afford to grant generous use and redistribution rights.

In the networked economy, companies have developed a variety of business models that facilitate widespread access to government and commercial geographic data. Many of these “New Economy” business models do not depend on royalties, minimize use and redistribution restrictions, and were built partially from, or enhance access to, government geographic data while generating revenue for the private sector:

-

Advertising. Vendors may offer “free” services in order to support advertising or sale of related products. For example, MapQuest’s Web site generates custom driving directions in order to attract viewers to Yahoo’s advertising.

-

Bundling with Protected Content. Vendors may bundle “free” data with proprietary software. For example, Caliper includes data with its proprietary GIS software.

-

One-Stop Shopping and Indexes. Vendors may attract others to their Web site by offering indexes and links to public and private datasets. Royalties also may be collected if and when the links

|

27 |

Many of the large data vendors who appeared before the committee remarked that they had never tried to enforce license terms or other contract rights against violators (Chapter 4, Section 4.4.1). |

|

28 |

This also suggests that accepting more restrictive license terms is unlikely to result in much of a price reduction. |

-

generate sales (e.g., Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc.’s Geography Network).

-

Delivery and Convenience. Vendors may repackage public data into more convenient and more powerful formats. During the early 1990s, Warren Glimpse built a successful business transferring publicly available TIGER/Line files to CD-ROM. The TerraServer online library of satellite imagery provides a more recent example.

8.4.2.4 Government Accountability

Some agencies need broader public dissemination rights than others in responding to their mandates and missions. However, all agencies must ensure government accountability. This basic requirement sets fundamental limits on agencies’ ability to accept restrictions on many types of geographic data. Fortunately, agency data acquisition and dissemination policies often are more concerned with accomplishing their core mandates and missions (including government accountability) than with economic efficiency.29 Fortunately, there are sometimes ways to work within such constraints. One common method is to allow users to examine, process, download, and/or print views without providing access to the underlying data. The following are examples of facilities in which users have little or no need to redisseminate underlying data:

-

Libraries. There are 1,297 libraries throughout the United States that provide no-fee access to government information in a partnership with the federal government. Many of these federal depository libraries (FDLs) provide a natural home for access to geographic information—often local, state, and federal information. During the paper map era, FDL program members ensured that government documents and data were available to members of the public. This capability was strengthened during the 1990s when many FDLs invested in onsite GIS workstations. Similarly, some state legislatures set up kiosks to provide public access to redistricting data.

-

Intranet Distribution. University libraries may negotiate contracts that allow them to share licensed data throughout their host institutions or within multiuniversity consortia. Members of the

-

university community often have access to the digital information resources day or night without leaving their offices or dorm rooms and even while traveling. Typically, licensing terms limit access to these electronic resources when outside the walls of the physical library to those who are formally affiliated with the academic institution or are consortium members.

-

Access to Derived Map Views. Some databases make selected data available for viewing and, in some cases, queries. Although they do not satisfy all possible needs, such databases may provide enough functionality, scope, and extent to meet basic demand while honoring the restrictions built into many license agreements. For example, the current implementation of The National Map lets anyone with Web access view detailed public geographic information about several cooperating local communities (e.g., Mecklenburg and Denver). Although online users can view and print combinations of detailed local information, they cannot download the underlying local government databases. MapQuest’s Web site is an example from the private sector in which views of the results of route-planning processing are made available but the underlying geographic data remain inaccessible.

Though often acceptable, these restrictions place severe limits on users’ ability to access and use data. For this reason, they normally should be thought of as setting a minimum standard of access that any government contract should meet or exceed,30 and they will not suffice in all instances. This is particularly true when the agency’s analysis of underlying data is at issue.

Although specific views may meet some public accountability needs, there are many cases in which agencies need to disclose the complete underlying data used to make government decisions. For example, views of data may be biased by those who compiled them or created the view generation software. The result may be computerized gerrymandering. Although the public does not have a right to proprietary data under FOIA, courts may not uphold agency decisions if underlying datasets are not subject to detailed public scrutiny.

8.4.3 The Agency as Licensor

Government mandates often may require or be best supported by free distribution of acquired data. At the federal level, licensing of government data to others typically occurs through specific legislative exceptions (e.g., CRADAs,31 Landsat Commercialization Act), and when there is a need to “pass through” commercial license provisions that apply to proprietary data that the government possesses (e.g., NGA’s Clearview Agreement and data from the USGS’s SPOT data archives in Sioux Falls). Otherwise, federal agencies are severely constrained in how they may limit access to data in which they possess full rights. The same also applies to many—though not all—state and local government agencies. These restrictions usually limit the ability of federal agencies and many local agencies to recover fees above the marginal cost of distribution.

The next subsection begins by discussing the revenue generation and pricing goals that an agency choosing to distribute data under license to outside users might pursue. The second subsection addresses how agencies can use licenses to achieve various noneconomic goals.

8.4.3.1 Revenue Generation and Pricing Goals

During the 1990s, many jurisdictions experimented with cost-recovery fees for geographic data. Ten years later, many of these entities have concluded that fee programs32

-

cannot recover a worthwhile fraction of government data budgets,

-

seldom cover operating expenses, and

-

act as a drag on private-sector investments that otherwise would add to the tax base and grow the economy.

|

31 |

CRADAs involving digital geographic data may or may not impose restrictions on the dissemination and use of the data produced or made more readily accessible through the CRADA. See the CRADA involving the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s hydrographic charts and the USGS-Microsoft TerraServer CRADA described in Chapter 4, Section 4.2.2. |

|

32 |

See Chapter 4 (Section 4.3). |

Recent blue-ribbon reports33 and statements before this committee34 suggest an emerging belief that cost-recovery experiments with public geographic data in the United States have failed to generate significant revenues while meeting the functions of government. This result may have been predictable because the demand for geographic data is particularly price sensitive. Many local government agency experiments in cost recovery sought prices beyond what most of the potential market was willing to pay, and so, buyers chose to do without the data or found substitute data. Local governments often found it cumbersome or politically impractical to embrace the price discrimination and other market segmentation strategies that their commercial competitors adopted. In addition, there is a limited market for local geographic data.

Nevertheless, state and local government agencies may choose to charge a higher fee,35 or local law may require them to set prices according to a particular standard (e.g., cost recovery). When local government jurisdictions choose to distribute geographic data through sale or license, agencies could limit the impact of such a decision by adopting the following strategies:

-

Price Discrimination. Price discrimination mitigates the economic inefficiencies associated with user fees.36 Agencies should resist calls to make data available to all clients at a single price.

-

Constrained Optimization. There are distinctions between (1) setting prices at higher than the marginal cost of distribution with or without regard to the revenue stream actually generated, (2) attempting to cover ongoing costs, and (3) attempting to become a “profit center.” If the goal is to finance ongoing operations while still providing affordable public access, agencies should charge the lowest price consistent with covering their variable costs. Agencies should resist the urge to set high prices if that results in the exclusion of a significant number of users.

|

33 |

See Chapter 4, footnote 95. |

|

34 |

See, for example, testimony of Bob Amos, William Burgess, Randy Johnson, and Peter Weiss. |

|

35 |

See Open Data Consortium [ODC], 2003, 10 Ways to Support Your GIS Without Selling Data. Available at <http://www.opendataconsortium.org> (hereinafter ODC, 2003). |

|

36 |

See Chapter 6. |

-

Minimally Restrictive Contracts. Previous sections have discussed a broad menu of licensing terms that agencies can demand from vendors. Agencies choosing to distribute data under license should offer similar terms. The October 1998 version of Canada’s Radarsat license provides an example of minimally restrictive government data licensing. This license relaxes constraints on inverting data back to their original form. The license design takes into account what users will do rather than what they might do.

8.4.3.2 Nonfinancial Reasons for Licensing by Government

Even when cost recovery is not a goal, agencies may sometimes use licenses to pursue other, nonfinancial policy goals. Such goals include attribution, negating implied endorsements, and risk management. Like any other license terms, these provisions should impose minimal restrictions on licensees’ ability to use and redisseminate data.

-

Attribution. Twenty years ago, it was easy for an author to cite each and every source consulted. Today, data products frequently extract, combine, and modify millions of data points from dozens of sources. In this new context, it may not be reasonable—or even feasible—to require users to provide an individualized attribution “tag” for each piece of data. Unless technological advances provide a solution, a simple statement that “This product contains data originally gathered and compiled by Agency XX” may have to suffice.

-

Negating Implied Endorsements. Geographic data are most valuable when they can be combined and repackaged to create new products. Agencies have a legitimate interest in reminding the public that these products are not endorsed or certified by the government. However, it is economically counterproductive for agencies to accomplish this goal by banning the extraction and modification of data altogether. A simple, prominent disclaimer is usually enough to negate any implication of endorsement or warranty.

-

Managing Risk. Indemnity and liability disclaimers are often reasonable and should be encouraged. Agencies are understandably reluctant to distribute data if doing so exposes them to liability. This is particularly true when data are distributed at or near

-

marginal cost. Disclaimers may legitimately extend to tertiary users, particularly if made as an explicit condition of the licensing arrangement with the secondary user. Well-designed disclaimers have little or no impact on consumers’ ability to extract, use, or manipulate data.

8.5 ACCOMMODATING A “CULTURE OF LICENSING”

Most data vendors’ terms and prices are negotiable, particularly for large transactions. Agencies with narrow, clearly defined projects rarely need unfettered rights in geographic data and may decide that it makes both short- and long-term sense to demand fewer rights in exchange for lower prices. Agencies also may be able to offer in-kind payments to vendors to lower dollar costs still further. These include, but are not limited to, such resources as publicity, access to agency expertise, and data verification.

The committee heard many examples of agencies that manage to negotiate favorable and often innovative contracts. That said, some agencies seem to believe that they cannot negotiate from a position of strength or else find negotiations burdensome. As a result, some agencies indicated that they accepted vendors’ opening offers at face value with little or no negotiation. Not coincidentally, these same agencies tended to have the most disappointing licensing experiences.

Finally, some agencies report that “uncertainties” in past licenses have deterred them from worthwhile projects. Yet they did not contact the vendor, much less demand that the uncertainties be resolved in their favor. The culture of licensing does not end once a contract is signed. Asserting contractual rights is a necessary part of living with licenses.

Conclusion: Given the expansion of licensing of geographic data in the marketplace, agencies cannot help becoming more sophisticated consumers when licensing is the only or best-value option in acquiring geographic data. Qualifications-based selection procurement accompanied by subsequent cost negotiations and, when appropriate, traditional competitive bidding practices can help agencies obtain the best possible terms.

Recommendation: Agencies should dedicate resources to training and knowledge-sharing among agencies in order to extract maximum public benefit from licensing. The Federal Geographic Data Committee’s working group and subcommittee structure provides a

VIGNETTE H.

THE SPATIAL SEMANTIC WEB DREAM

“With the growth of the World Wide Web has come the insight that currently available methods for finding and using information on the Web are often insufficient. …Today's retrieval methods typically are limited to keyword searches or matches of substrings, offering no support for any deeper structures that might lie hidden in the data or that people typically use to reason; therefore, users often may miss critical information when searching the Web. …The advent of the Semantic Web promises better retrieval methods by incorporating the data's semantics and exploiting the semantics during the search process.”37

Dianne Hamilton has created a land-ownership-parcel dataset and would like to make it known and available to the world. As she completes a minimal set of online metadata questions, she is asked to supply the “type of dataset.” She selects “parcel” from a pull-down menu. The system responds by asking her to select from several definitions of parcel or to construct her own definition. She clicks the supplied definition of “land ownership parcel” (as opposed to “package parcel” or “land use parcel”) and the remainder of the metadata entry process becomes simpler because the top items in the pull-down menus for subsequent entries are options that most closely comport with land ownership ontologies.38

Ms. Hamilton’s choices in her remaining entries automatically tie her data to one or several ontologies, thereby enabling semantic search engines to find her dataset using criteria based on her supplied deeper understanding of the content. Although Ms. Hamilton, a novice dataset creator and publisher, will not know and cannot supply the technical description and details of models used to construct her data product, the process she has followed nevertheless ensures that such details can be incorporated within and later automatically extracted from her published dataset.

For the Spatial Semantic Web to reach its full potential, automated searches must be able to reach and explore actual geographic datasets as well as their metadata. Without full access to the dataset, data semantics cannot be used to find and assess the suitability of Ms. Hamilton’s data for an explicit need. Additionally, searches that rely on data similarity assessments require access to the data rather than just metadata.

In the past, Ms. Hamilton would never have made her dataset fully available on the Web because it was so easy for others to simply take it. However, because she can now readily incorporate standard license language in the metadata and identifiers in the geographic data, she has developed confidence in her ability to track and substantially reduce such free riding. By taking this legal and technological approach, Ms. Hamilton helps the Spatial Semantic Web reach its greatest functionality and thereby enhances discovery and usage of her offerings.

In the end, the Spatial Semantic Web dream comes down to this: Can a combined technological and licensing infrastructure be developed that supports easy and efficient online entry of licensing and technical information?