3

The Geographic Data Market: Offerings, Players, and Methods of Exchange

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Efforts to enhance geographic data production, distribution, and use—the underlying goal of government licensing policy—benefit from understanding the geographic data market. The interaction between public and private sectors in this market is complex. It is also changing, with vendors announcing new business models every few months.

This chapter begins by summarizing the types of geographic data that society uses. Next, it describes the structure of the marketplace and reviews the “value chain” that results from successive actors collecting, merging, and transforming raw data into products and services within the marketplace. The chapter then discusses dominant business models in geographic data transactions and the factors that influence contractual terms. The final sections summarize common license models and data flows to and from the public sector.

3.2 TYPES OF GEOGRAPHIC OFFERINGS

Today’s digital technology permits the rapid acquisition and maintenance of a vast inventory of information about Earth, ranging from demographic descriptors to well-defined uses of land. Geographic data types can be categorized in many ways. Here, we differentiate data that

describe the natural world from those describing human action.1 Numerous natural features characterize Earth’s physical processes, patterns, and conditions. These features, described in more detail in Appendix C, relate to topography, hydrology, physical geology and geography, weather, energy resources, and natural resources and hazards. In contrast, the constructed environment constitutes the human geography at Earth’s surface. These features include built structures and invisible boundaries that reflect political, economic, and locational decisions. Such data can be broadly grouped into five categories of human action: (1) transportation, (2) institutional locations (e.g., colleges or universities, schools, and libraries; hospitals and nursing homes; industrial sites; parks and historic landmarks and sites), (3) energy-related infrastructure, (4) administrative and legal boundaries, and (5) hazardous locations.

3.2.1 Focus of Government Geographic Data Interests

Government agencies usually focus on data needed to address their own mandates, missions, and goals. Nonetheless, government information policy aims to ensure that most data gathered for one government purpose are widely available to support additional governmental and nongovernmental uses. Geographic data priorities vary by agency and level of government, but some data types are particularly versatile and tend to support multiple missions. In the federal government, the National Research Council (NRC)2 identified three geographic data themes as being at the foundation of government business: Terrain (elevation) data, orthoimagery, and geodetic control.3 NRC (1995) also highlighted additional “framework” data types that are often high priorities for agencies: transportation networks; political, administrative, and census boundaries; hydrology (location, geometry, and flow characteristics of rivers, lakes, and other surface waters); cadastral (land ownership) data; and natural resources data (geology, ecosystem distribution, soils, and wetlands). The Geospatial One-Stop initiative is developing standards for seven of the aforementioned data types (excluding natural resources), confirming their continued importance to government. Given government buying power, it is not

surprising that geographic data markets tend to produce the data types in which government is most interested.

3.3 STRUCTURE OF THE GEOGRAPHIC DATA MARKETPLACE

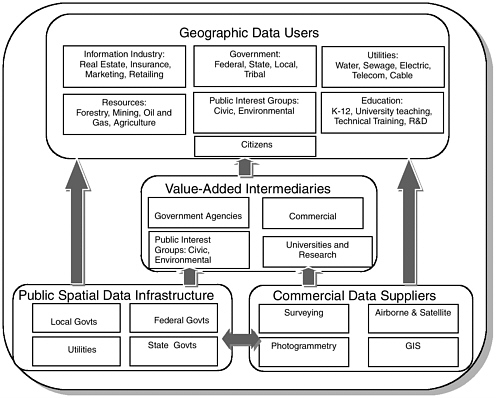

The geographic data marketplace is a network of government suppliers, commercial suppliers, value-added intermediaries, and users (Figure 3-1). This range of players is much broader than it was 30 years ago, when data capture and production were largely monopolized by government mapmakers.

Technological advances, coupled with increasing demand for geographic information and analysis, have reduced barriers to entry into the market. Consequently, the commercial sector is vibrant and competitive. Commercial firms generate a wide variety of products and services, including off-the-shelf data and information products, for-hire data acquisition services, and custom data processing services. In addition to data, firms may offer specialized access and analysis tools, and/or Web-based services that support a variety of applications including in-vehicle navigation, location-based services, Web mapping, and asset tracking. This diversity of data products and services continues to grow, to the benefit of users.

At the most basic level, government (the public spatial data infrastructure4) and commercial organizations (commercial data suppliers) (Figure 3-1) provide data collection and basic geographic information layers. Commercial suppliers also supply more specialized layers for private clients. On the government side, NASA, NOAA, NRO, and USGS5 operate Earth-observing satellites. NOAA, NASA, and other government agencies also operate aircraft that collect imagery. Various public agencies also create both basic and mission-specific geographic information. For example, USGS creates hydrology layers using in-house staff and private contractors. Most federal agencies make such information available to the public at the cost of reproduction as paper maps or digital data layers.

FIGURE 3-1 Geographic data marketplace. The concepts of the geographic data market and the public spatial data infrastructure are distinct. Government resources provide an infrastructure from which the marketplace for geographic data products and services emerges. Government also plays an important role inside the marketplace through its procurement of geographic data products and services. SOURCE: Adapted from: X. R. Lopez, 1996, Stimulating GIS innovation through the dissemination of geographic information, Journal of the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association 8(3), 24–36.

On the private side, several commercial companies operate Earth-observing satellites or aircraft. Additionally, numerous companies create basic and client-specific information layers under contract or as licensed products.

Value-added intermediaries provide additional value to users by enhancing preexisting public and private information. These enhancements include creating market-specific information layers, developing informa-

tion access and analysis tools, and providing Web-based services. Intermediaries also combine datasets to meet user requirements, and improve the detail, accuracy, and precision of underlying datasets.

The commercial sector is a major provider of value-added products and services. For example, Navteq, Inc., adds value to publicly created geographic information sets (i.e., by including additional information, correcting errors, and keeping the information current) and bundles them with information-access software for in-car navigation. Researchers and government agencies also engage in value-adding activities. For example, the USGS bundles Landsat imagery, hydrology, digital line graphs, topography, land use, and other basic layers with commercial Web-access software (ArcIMS [Internet Map Server]) to create elements of The National Map.6 Public interest groups may also add value by analyzing and repackaging data to highlight a trend or issue.

Intermediaries also help government disseminate information. Traditionally, the principal intermediaries were nonprofit libraries and government depositories. Today, commercial data vendors, scientists, academics, and other government agencies use the Web and online search capabilities to provide government data to users. Alternatively, some agencies exploit the Web to eliminate intermediaries altogether.

Geographic data uses tend to be demand driven. Users increasingly want data or combined data/software offerings tailored to their own specific problems.

3.4 THE GEOGRAPHIC VALUE CHAIN

The geographic offerings and affiliated services described in the preceding section flow through numerous public and private organizations to form the geographic value chain. The flow is governed by various agreements, including licenses, and is enhanced by standards.7 This section describes the evolution of the value chain and the levels within it.

|

6 |

The National Map “provides public access to high-quality, geospatial data and information from multiple partners to help support decisionmaking by resource managers and the public.” See <http://nationalmap.usgs.gov>. |

|

7 |

For example, the Open GIS Consortium has developed specifications that have enabled growth in the Web services marketplace for geospatial applications, and the Federal Geographic Data Committee has coordinated the development of more than 30 standards for frequently used government data. |

3.4.1 Evolution of the Value Chain

Until the 1980s, maps existed only on parchment, vellum, or paper. Reproducing a map was difficult, and analysis of geographic interconnections between different maps was practically impossible. During the early 1980s, however, mapping technology evolved with the broader computer revolution, and digital maps emerged. The difficult task of making physical copies became easy, facilitating sophisticated data manipulation and geographic analysis across space and time.

These changes affected the way that people work. For example, firefighters traditionally relied on paper maps of vegetation, roads, and topography. They used their knowledge of fuel types, weather, and terrain conditions to estimate how a fire would spread. Today, they call on digital information and supporting computer projections to create detailed forecasts of how fire will burn across space and time.

The range of data and services available to society has grown rapidly over the past two decades. Today’s value chain embraces the full range of activities, from raw data collection to mapmaking to query and analysis tool development and Web-based services.

3.4.2 Components of the Value Chain

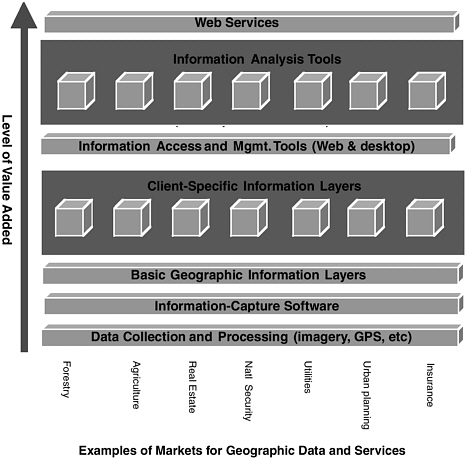

We identify seven levels within the value chain for geographic data and services (Figure 3-2), starting with initial data collection and processing, and moving upward to Web-based services.8

-

Data Collection and Processing. This level includes gathering and initial manipulation of raw imagery (e.g., optical, radar [radio detection and ranging], and lidar (light detection and ranging), Global Positioning System (GPS) points, or other types of data (e.g., demographic, economic, or health data). Because many of

|

8 |

Not shown in Figure 3-2 or discussed in this section is product differentiation by scale or resolution. This adds a third dimension to the value chain. For example, Landsat and Orbital Image Corp. have very different products. Although each offering occupies the same level in the value chain, the former has 30-meter spatial resolution compared to 1 meter for the latter. Needless to say, their prices and user groups are very different. For a discussion of pricing differentiation techniques for information products and services, consult C. Shapiro and H. Varian, 1998, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy, Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press. |

FIGURE 3-2 The geographic data value chain. The vertical axis represents the progression (from bottom to top) of the increasingly complex offerings described in text. The horizontal axis carries examples of typical markets for geographic data products and services. Boxes that span the figure illustrate levels in the value chain where market demand is sufficiently high to support standard offerings across multiple markets. Other levels of the chain, illustrated by isolated square boxes, focus on particular individual markets.

-

the foundation and framework data layers used by government (e.g., topography, transportation, hydrology, land use, and land cover) are derived from satellite and airborne imagery and GPS data, this report focuses on these data. Imagery collection tends to have high fixed costs, including up-front investments in aircraft, sensors, or satellites. On the other hand, imagery provides a base

-

for information collection across a variety of markets. This means that firms can usually offer imagery capture services and products across multiple markets.

-

Information-Capture Software. This software lets users create digital geographic information layers by interpreting imagery or GPS data, inputting data sources (such as demographic datasets), or scanning or digitizing paper maps. Imagery and raw data are converted into geographic information system (GIS) layers through computer-aided manual interpretation or automated image classification.

-

Basic Geographic Information Layers. This level includes many of the information types most useful to government. These foundation and framework layers (e.g., transportation, land use, topography) are often generated using information-capture software to interpret raw data. Like data collection services, basic geographic information layers often span multiple markets (Figure 3-2). For example, transportation maps showing addresses and street names may be useful to private motorists, disaster response agencies, delivery companies, insurance agencies, and school districts. Theoretically, the existence of these multiple user groups can support speculative investment in the base layer.

-

Client-Specific Information Layers. Many clients have unique needs. In these cases, the market for data is limited. For example, detailed timber type maps of a particular lumber company’s classification scheme offer little value to other groups. Such maps are more likely to be produced through a one-off, for-hire data acquisition and processing service. In this situation, licensing—with its emphasis on multiple licensed users—is irrelevant.

-

Information Access and Management Tools. To be useful, geographic data must be accessible through desktop-computer, Web-based, or mobile applications. Several private and public organizations have created powerful offerings by bundling information-access or -processing software with public information to meet needs that span multiple markets (see Box 3-1). 9 Access tools

-

such as Space Imaging’s GeoBook,10 also serve multiple markets because the underlying information management and query algorithms usually can be ported from industry to industry at minimal cost.

|

BOX 3-1 Commercial firms have developed a wide variety of innovative information access tools:

|

|

10 |

Available at <http://www.spaceimaging.com/solutions/geobook/>. |

-

Information Analysis Tools. Perhaps the most sophisticated uses of geographic information are to predict future events (e.g., how wildfires will burn) and prescribe future actions (e.g., how a community should minimize wildfire risk, given limited resources). Information analysis tools for these tasks tend to be highly specific, and are usually aimed at a single user or group of users. Such tools usually are built on top of standard geographic database management software (such as those licensed by IBM, Intergraph, Microsoft, Oracle, and Sybase). Firms typically sell management software off the shelf or offer consulting services to users who want to build their own analysis tools.

-

Web Services. Web services11 for mapping and geospatial analysis are a recent development and have adopted several models. One widely used Web-based mapping service is MapQuest.12 Visitors to MapQuest’s site can obtain directions and maps to any address in the United States, Canada, and several other countries. The site supports itself by posting advertisements from restaurants, hotels, and other attractions. This revenue model is relatively simple. Since MapQuest is a “stovepipe” application, it does not link with data from other Web-based mapping applications and faces few licensing or copyright issues.

FEMA’s Hazardmaps Web site13 and the New South Wales Resources Atlas14 represent a different approach. These Web services employ open standards to facilitate rapid access and integration of geographic data from various sources on the Web. The open standards also make it easier to access and apply services provided by other developers or vendors across the Web.15

|

11 |

Web services are self-contained, self-describing, modular applications that can be published, located, and invoked across the Web. Web services perform functions that can be anything from simple requests to complicated business processes. Once a Web service is deployed, other applications (and other Web services) can discover and invoke the deployed service (Open GIS Consortium [OGC] On-Line Glossary, at <http//:www.opengis.org>). |

|

12 |

Available at <http://www.mapquest.com>. |

|

13 |

Available at <http://www.hazardmaps.gov>. |

|

14 |

Available at <http://atlas.canri.nsw.gov.au>. |

|

15 |

Any data server based on open standards can be accessed by any service using the same open interface. The decision to share data is strictly a decision on the part of the owner of the data. Typically, a Web service is “published” to a |

Developments in geospatial Web services reflect rapid growth in information technologies in this area, and a new breed of geospatially enabled Web services is emerging that lets users combine geographic data and analysis tools from multiple providers. These technologies present complex licensing issues because users can now access multiple information repositories and/or service providers. Each repository may have its own licensing and copyright rules, and multiple providers may demand payment.16 To attack the problem, members of the OGC are developing an open standard for Web pricing and ordering.17 In this approach, a “rule base” captures each provider’s rules and revenue model required for a Web-services-enabled transaction. A broader approach would involve metadata for licenses appearing within or alongside standard geographic information metadata (e.g., ISO 19115 Geographic Information—Metadata18) to support digital rights management approaches.19

3.5 DATA ACQUISITION-FOR-HIRE SERVICES VERSUS DATA LICENSING

Value-chain businesses in the geographic data and services community usually follow one of two dominant business models: Under one model, users purchase data, with unlimited rights of use, with the provider possibly retaining the right to engage in subsequent transactions with other users. In the other dominant model, users license data, which restricts the uses that they can make of the data and/or their ability to transfer the data to others.20

Except for commercial off-the-shelf software and search/manipulation tools, the geographic information market traditionally has been based on data acquisition-for-hire services. In this model, governments and businesses

|

|

registry that can be searched just as catalogs search for metadata about geographic data. |

|

16 |

See the related discussion of the “complements problem” in Chapter 6, Section 6.2.1. |

|

17 |

|

|

18 |

Also available as OpenGIS Abstract Specification Topic 11 at <http://www.opengis.org/docs/01-111.pdf>. |

|

19 |

See Chapter 9, Section 9.3, with attention to Boxes 9-1 and 9-2. |

|

20 |

See Chapter 1, Section 1.4, for the definitions of purchase and license. Of course, the difference between purchasing and licensing can be a matter of degree, so that a license with relatively few restrictions is very similar to an outright purchase. |

buy services from vendors. These services include collecting imagery or other geographic data and converting them into meaningful information. Ownership of the information typically resides in the customer.21

In the early and mid 1980s, commercial satellite imagery companies SPOT and EOSAT22 began using licenses to distribute their imagery.23 Since then, new commercial satellite companies have invariably followed the product-for-license model.

Although most airborne imagery collection companies still operate on a for-hire basis, the emergence of mass markets, coupled with falling computer hardware prices, has encouraged firms to create more and more licensed products. Many of these products are aimed at large numbers of small consumers, and bundle information access software with large geographic datasets. Examples include digital orthoimage compilations, transportation maps, and digital line graphs (i.e., line map information in digital form) (see Box 3-1).

Shifting from a data acquisition-for-hire model centered on a few large government purchasers to a mass-market, product-for-license model requires a different business organization (Table 3-1). In the data acquisition-for-hire model,24 the service provider faces comparatively less venture risk because fixed costs are relatively low and the majority of costs are in variable labor hours. The product-for-license model25 faces comparatively greater venture risk because the producer speculatively invests in product creation without assurance of future revenues.26 For example, a city

|

21 |

Ownership in this instance means that, with reference to any data to which copyright applies, the customer is the copyright holder and, with reference to any data to which copyright does not apply, the customer has exclusive or nonexclusive rights to use and make the information available to others without restriction. See also Chapter 1, Section 1.4, for the definition of ownership as applied to the licensor–licensee relationship. |

|

22 |

Earth Observation Satellite Company. See further discussion in Chapter 4, Section 4.3, under the topic of Landsat. See also NRC, 1995, Earth Observations from Space: History, Promise, and Reality, Washington, D.C., National Academy Press, pp 109–115; NRC, 1997, Bits of Power: Issues in Global Access to Scientific Data, Washington, D.C., National Academy Press, pp 121–123. |

|

23 |

Personal communication from Neal Carney, Spot Image Corp., January 2004. |

|

24 |

The acquisition of collected-to-specification aerial photography by government from the commercial sector typically has followed this model. |

|

25 |

The acquisition of commercial satellite imagery by government typically has followed this model. |

|

26 |

Although aircraft can be rented rather than purchased, the majority of costs are from items that must be purchased, such as cameras, and data and film processing systems. |

government may purchase orthoimagery either by hiring an aerial data firm to collect and process the imagery or by purchasing previously collected airborne or satellite imagery under license. In the data acquisition-for-hire case, the city can specify the collection time, area, and scale; it also will own the resulting imagery. Additionally, the service provider faces very little risk on the specific transaction as long as it fulfills its contract, because the entire cost of the imagery is recovered from a single purchaser. Conversely, a company that creates consumer data products faces a significant risk that it could collect and process imagery that will generate no or insufficient future revenue to recover the investment. However, once the product is established in the marketplace, profit margins are usually higher in the product-for-license model than in the acquisition-for-hire model. The key to maintaining these margins is to restrict the ability of users to transfer the data to other users by licensing rather than selling the data.27 Without these margins, firms would lack an incentive to risk developing new products without a proven market.

From the city government’s standpoint, licensed data have benefits and drawbacks. On the benefits side, licensed products may have greatly reduced price because acquisition costs can be shared over multiple licensees. On the costs side, licensees must acquire existing product with prespecified time, area, and scale. Customers familiar with the intimacy of a service-for-hire contract also may be put off by the lower level of customer support found in the sale of a standard product under license. Furthermore, their ability to share the data usually will be restricted by the license.

In some cases, the cost advantages of licensed data should offset the disadvantages of losing downstream uses of the product and foregoing the ability to customize data specifications. In other cases, license prices are sometimes comparable to the cost of an acquisition-for-hire contract tailored to the customer’s unique specifications. Licensing normally will be unattractive in these circumstances.

Distribution strategies continue to evolve as vendors experiment in the marketplace. For example, one approach is for a large portion of upfront costs to be borne by one user or a small number of users while the vendor retains the rights to distribute the data to others (e.g., Intermap’s NEXTMap Britain venture). VARGIS28 has used a business model in which the primary user pays for a majority, but not all, of the acquisition

TABLE 3-1 Characteristics of Acquisition- for- Hire Service Versus Product- for- License Business Models

|

|

Acquisition- for- Hire Service: |

Product- for- License: |

|

|

Characteristic |

Custom Consulting |

Standard Data Acquisition and Processing |

Geographic Consumer Product |

|

Definition |

Typically one- off service engagements focused on exploring the extension of an existing technology into a new market, or a new technology into an existing market. |

Data acquisition and processing services are sufficiently standardized that procedures can be codified in ISO standards and/or manuals. |

Large numbers of customers license standard deliverables. Vendors rely on a high degree of automation to fill requests. |

|

Level of standardization |

Typically contractual reference to some industry standards. |

Deliverables (e. g., resolution, type of imagery, currency) vary slightly for individual customers so that services cannot be completely automated. |

Products are fully defined and codified. Orders are automated and human intervention is seldom required. |

|

Amount of producer/customer interaction |

High. Client and producer work together to define processes and specify results. Risky projects place a premium on trust. |

Medium high. Client and producer work together to specify results. |

Medium to low. Customer typically licenses product without interacting with the producer. |

|

Reliability of offering |

Low. There are no guarantees that the technology will work. The deliverable may continue to evolve as the project proceeds. Higher reliability if performance standards are required. |

Medium. Procedures are standard, but deliverables vary from client to client. Furthermore, there is a risk that procedures may be misapplied. |

High. Vendors realize that unreliable products can cause serious market- share loss. Clients expect and demand fitness for use. Consumer product laws ensure quality. |

|

Required level of internal investment |

None. Client pays for entire project. |

Minimal. Standardized procedures are relatively inexpensive to develop. |

Significant. Capital investment in software development, product definition, and management costs can be substantial. |

|

Economies of scale |

None, or acquired through sharing. |

Medium. Technology and management breakthroughs frequently lead to faster and less expensive processes. |

Large. Volume sales drive down per-unit costs. |

|

Marketing |

Publication of articles, speeches, and workshops. |

Customer testimonials are important, as are articles, speeches, workshops, and brochures describing standard services. |

Advertisements and targeted mailings. |

|

Pricing |

Estimates by hourly rate or “cost plus” contracts. |

Estimates by hourly rate or fixed- fee contracts. |

Catalogue pricing based on a standard price per unit. |

costs in exchange for a right to distribute these data to others. The primary user usually asks for rights to freely distribute these data within its organization and to its traditional partners, and agrees not to sell the data and to try not to distribute the data further. The vendor then markets the data to others. The vendor has reduced risk in creating the datasets initially, and the primary user has more influence over the nature and extent of the data being created.

3.6 FACTORS INFLUENCING THE CONTRACTUAL TERMS OF DATA SHARING

Geographic data offerings from the commercial sector typically are differentiated by data characteristics (e.g., currency, spatial resolution, spatial accuracy, content and classification accuracy, spectral and radio-metric properties, data format, ease of access and use, availability) and use restrictions. Data characteristics determine the cost of data collection and processing. More stringent data characteristics (e.g., more accurate, more current) typically require higher production expenditure, which normally is reflected in the price consumers pay. Broader use rights also tend to increase the price to the consumer, reflecting the higher value of the rights rather than any increase in cost.

Data customers lie along a continuum. Some have stringent and relatively inflexible requirements. For example, a county fire chief who needs to support emergency response services may require current, accurate, high-spatial-resolution data so that she can locate and identify structures, trees, and open spaces. She also may need to share the data with other public agencies. Unless a licensed commercial product meets these needs, she normally will rely on commercial data-acquisition services instead.

Other customers have more flexible needs. For example, a private forest appraiser may be willing to accept dated information at a low spatial resolution subject to use restrictions. Because forests change slowly, recent imagery is not especially valuable. Furthermore, the appraiser is interested in forest type rather than individual trees, and so the spatial resolution can be coarse. Finally, redistribution needs typically are limited to a single landowner.

Many consumers have missions that allow them to accept, and make tradeoffs between, a wide range of data characteristics. In such situations, the commercial sector often finds that government data have supplanted its potential market. On the one hand, flexible user requirements usually mean a large market—the type of market that might attract commercial

investment. On the other, this flexibility is attractive to government because the same data can satisfy multiple governmental purposes. Commercial vendors trying to generate profits from the lower portions of the value chain (i.e., selling imagery and other geographic data gathered primarily from sensors or direct observations with little added value) often are concerned that the availability of unrestricted government data undercuts their potential markets.29

3.7 COMMON TYPES OF LICENSING STRATEGIES

Companies have invented many types of licensing strategies to sell their data (see Appendix D). Prominent market strategies include

-

Mass-Market Strategies. Industry is increasingly moving toward mass-market products, and some observers believe that these products have a strong future.30 In this environment, licensing normally requires “click-wrap” and “shrink-wrap” form agreements. Mass-market firms have repeatedly expressed interest in offering special rates to government users.31

-

Thin-Market Strategies. Many firms operate in markets where would-be buyers and sellers find it hard to locate one another. Licenses that feature minimal restrictions on reuse and redistribution are often feasible in these circumstances. Aerial survey firms traditionally have followed this minimalist model. Geographic Data Technologies (GDT) extends the strategy by transferring county-scale datasets to local governments without restriction. As a practical matter, such disclosures are too fragmented to affect demand for GDT’s nationwide products.32

-

Niche-Market Strategies. Many companies collect large datasets and use them to create multiple, highly specialized products for transportation, navigation, automotive, enterprise/business, Internet,

-

wireless, and other specialized users.33 Licensees typically receive broad-use and redistribution rights with these client-specific information layers. Such licenses are feasible because (1) the derived products are so specialized that it is more or less impossible to reconstruct the vendor’s original dataset and (2) the derived products have few potential customers. Several firms recently have begun marketing highly specialized products to government users.34

-

Bundled Products. Many geospatial product offerings bundle data and software together. In many cases, the data are publicly available and would have little value if they were sold separately. Instead, most of the value—and license restrictions—center on the software component. Some companies claim that mass-market software is the future of commercial geospatial technology.35

-

Transactional Services. Some firms add value by assembling the permissions needed to make new products from existing data. Some of these companies sell the resulting products themselves,36 whereas others work as consultants.37 For example, the U.S. Census Bureau hired Harris Corporation in 2002 to obtain street-centerline data. Harris plans to obtain much, though not all, of the data through negotiations with local governments.38

|

33 |

Navteq, Inc., sells to automotive, enterprise/business, Internet and wireless, and government customers (testimony of Cindy Paulauskas, Navigation Technologies Corp.); licensing has a strong future in transportation, navigation, and other niche applications (testimony of Bryan Logan). |

|

34 |

Examples include Navteq, Inc. (testimony of Cindy Paulauskas), DeLorme (testimony of David DeLorme), and AirphotoUSA. |

|

35 |

See, for example, testimony of David DeLorme. |

|

36 |

Testimony of Don Cooke describing how GDT assembled a nationwide geographic database by obtaining rights to county- and local-scale datasets. |

|

37 |

Testimony of Chris Friel describing a project in which a geology consulting firm obtained permission to use and combine GIS software, database software, e-commerce software, geology data, USGS maps, insurance casualty data, and street-centerline information to develop a new property insurance estimator product. Chris Friel also testified that his project was hampered by the fact that the data that he needed were owned by different entities and that he needed permission from all of them to produce his product. We discuss this “complements problem” in some detail in Chapter 6, Section 6.2.1. |

|

38 |

Testimony of Robert LaMacchia, U.S. Census Bureau. |

-

Guaranteed Revenues. Many firms use guaranteed commitments from one or two large customers to manage risk in the broader market. In return, large customers usually receive significant bulk discounts or generous redistribution rights. In principle, such licensing strategies can encourage investment and provide data that might not otherwise exist to both agency personnel and the private sector.39 Guaranteed revenue models are particularly important in the satellite industry. Examples include National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s (NGA’s) Clearview agreement, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) SPOT and Earthsat agreements.40 In these cases, payments from a single large user cover the cost of production, ensuring that the data are produced, and they permit the data to be widely disseminated to users who pay little or nothing for them.

An alternative example, from the airborne industry, is Intermap’s NEXTMap survey of Britain, for which a small number of users paid a substantial portion of the upfront costs but Intermap retained the right to sell the data to other users.41 This arrangement has the benefits of ensuring that data that are highly valued by some users are produced but that they are also available to other users, to whom the data may have less value, at lower prices.42

-

Unrestricted Use. Unrestricted use and redistribution rights become feasible at the limit where guaranteed revenues cover a large proportion of the vendor’s investment. In these circumstances, vendors are often willing to take a calculated risk that buyers will not go into competition with them.43

|

39 |

As such, these guarantees sometimes are also interpreted as subsidies that could have positive impacts on public and private sectors. |

|

40 |

The Clearview contract gave industry a large guaranteed purchase in exchange for a 75 percent per-unit price cut (testimony of Gene Colabatistto, Space Imaging); USDA has obtained volume discounts from SPOT, Earthsat, EOSAT, and Space Imaging (testimony of Glenn Bethel, USDA). |

|

41 |

Testimony of Michael Bullock, Intermap Technologies, Inc. |

|

42 |

As we discuss in Chapter 6, Section 6.2, guaranteed revenue arrangements in which a single user pays all or most of the costs of production while other users obtain the data at prices that are no greater than the marginal cost of distribution are likely to do reasonably well in achieving efficiency in both the production and distribution of information. |

|

43 |

Although not unrestricted, NGA’s Clearview agreement reduced vendors’ need to resell data by providing a large commitment over three years (see Appendix D, Section D.3; Roberta Lenczowski, NGA, personal communication, |

-

Custom Agreements. For large transactions, most vendors are willing to write specialized contracts that tailor use and redistribution rights to individual needs. Custom agreements deliver value by ensuring that the customer does not acquire more rights that it needs.44

3.8 EXCHANGE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE PUBLIC-SECTOR MARKETPLACE

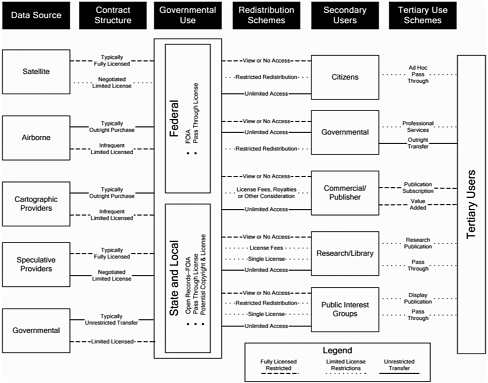

Agencies rely on a wide variety of transactions to acquire and distribute geographic data (Figure 3-3), including memorandums of understanding between agencies, a variety of product-based contracts and licenses, and consulting or data provisioning service contracts. Figure 3-3 does not attempt to characterize all possible arrangements, but it illustrates many of the typical relationships between players upstream and downstream of government. Data sources on the upstream side of government include at least five readily identifiable groups:

-

Satellite data providers have traditionally used restrictive licensing strategies to support large upfront technology and launch costs. Although firms historically have focused on selling licensed data to the defense and intelligence communities, firms are increasingly willing to negotiate broad reuse and redistribution rights on some types of data.45

-

Airborne data providers traditionally have followed a consulting services model in which customers receive all ownership rights,

|

|

2003). Space Imaging would probably agree to unlimited redistribution rights under appropriate circumstances (testimony of Gene Collabatistto). |

|

44 |

Vendors usually want to know the customer’s business plan before setting prices (testimony of Chris Friel, GIS Solutions Inc.); vendors who understand the customer’s application can usually offer a better price (testimony of Cindy Paulauskas). As we discuss in Chapter 6, Section 6.2, price discrimination, where different users pay different prices for the same information, may be necessary for efficient production of information such as geographic data. At the same time, users may be unwilling to reveal to the seller the true value they place on the information in order to reduce the price that they actually pay. See Chapter 6, Section 6.2.1, for a discussion of the underreporting problem. |

|

45 |

See, for example, a discussion of the Clearview contract negotiated by NGA with Space Imaging and DigitalGlobe (Appendix D, Section D.3). |

-

including intellectual property rights, to acquired data. Data obtained under these service arrangements often are treated as “works for hire” that vest copyright ownership in the customer.46 However, several airborne companies (e.g., AirphotoUSA, DeLorme, MapTech, and Navteq) have recently experimented with licensing data to government.

-

Cartographic data providers, including land ownership parcel conversion firms, add value to basic datasets. Most transfer all rights to customers. However, some cartographic firms license data to customers, particularly in cases where they are called on to provide data maintenance services on a recurring basis.

-

Speculative product or online service providers develop data or online database services in hopes of making multiple sales. Data and services typically are licensed so that the provider retains underlying ownership.

-

Government agencies often are required to provide public access to their data under state Open Records laws and the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). However, some local government agencies, through exceptions to FOIA, sell data under license at fees that are well above the marginal cost of distribution. Agencies license data for nonmonetary reasons as well. These include providing an inducement for collaboration, protecting data security, ensuring data timeliness, and, at times, guaranteeing credit and attribution.

On the downstream side of government, there are two levels of users: secondary and tertiary (Figure 3-3). Secondary users have access to government data and use them directly. Some secondary users may make relatively few changes to the data; others add extensive value to meet their needs. Tertiary users are downstream users who receive government data through intermediaries who may or may not have made major changes to the data. Licensing controversies often center on restrictions that limit government data availability to secondary and tertiary users.

FIGURE 3-3 Conceptual diagram of geographic data contractual arrangements for data flowing to and from government.

The report recognizes five groups of secondary users, each of which can, and often does, distribute data to tertiary users:

-

Citizens commonly seek public data to have “access to the means of decision making”47 or to satisfy some personal question or need. Because their motives are noncommercial, citizens generally expect to obtain public data at the marginal cost of reproduction with few or no restrictions. At the same time, citizens are usually end users: That is, they seldom redistribute data to tertiary users.

-

Public interest groups often advocate positions or agendas that benefit their constituents directly or indirectly. Although public interest groups generally have no profit motive, the social goals they seek for constituents (tertiary users) often have economic ramifications. Public interest groups nearly always provide data to tertiary users through some form of advocacy, publication, or display. This may change in the future as public interest groups explore making entire databases and online software processing and Web server capabilities available so that constituents can investigate data for themselves.

-

Commercial users (e.g., engineering firms, surveyors, developers, contract researchers, publishers) take advantage of public information in their businesses and often redistribute it. Many commercial digital mapping products (e.g., some GDT and DeLorme products) depend on public geographic data for initial product development and updates. Normally, commercial users add value by making products or services more responsive to consumer need. Other commercial firms (e.g., utilities, information firms, resources firms) use government data without redistributing them to tertiary users. Commercial users often are willing to pay fees for government data, although they obviously try to minimize costs whenever possible. Publishers often are willing to pay royalties based on sales.

-

Nonprofit research, academic, and library communities exist for the expressed purpose of redistributing data for knowledge advancement. Typically, they cannot afford to pay substantial royalties or fees.

-

Government agencies use data from other levels of government and/or other agencies to perform their functions.

Government geographic data, like all data, derive their value from use. The existence of large numbers of secondary and tertiary users makes government geographic data particularly valuable. Agencies typically distribute data as (1) the “native” or original data or (2) a “view” of the data product.48 The distinction between these two forms (see Table 3-2) is important for licensing and agency missions. For example, FOIA (or

its state equivalent) usually requires agencies to make native data available. This provides data in the same form as that maintained by government. 49 Conversely, presenting a view of the data product seldom satisfies FOIA.

Table 3-2 Comparison of Common Modes of Government Geographic Data Availability

|

Characteristic |

View of Data Product |

Native Data |

|

Form |

Preprocessed Predetermined form and format Limited scope (possibly) Limited extent (format dependent) |

Unprocessed Data in native form and format Variant-form, value-added service Full scope and extent (by request) |

|

Audience |

Ad hoc users Value-added resellers |

FOIA and Open Records requests Institutional (research, public, private) Ad hoc and formal |

|

Access mechanism |

Web based Map book or map series Standard media |

Standard media Web based Hard copy |

|

Value proposition |

Application services Web services Subscription services |

Official public record Unvarnished content and scope |

|

Mandate/mission satisfied |

Customer service Good will Transaction cost avoidance |

Meet FOIA and Open Records Statutory obligations Supports users |

|

49 |

Exceptions can occur when government puts native data in a form that is more convenient to the requester, or when government acquires data under license (in which case dissemination of these data under FOIA is subject to the terms of the agreement [Chapter 5, Section 5.4.2.1]). |

Web-based viewing methods that couple data with applications shift the costs of data discovery, selection, and delivery from the agency to the user. Views also lend themselves to subscription services where users pay for value-added features.50 By contrast, the value of native data lies in its scope, its unvarnished content, and its status as the official public record.

3.9 SUMMARY

Geographic data come in many forms and are widely used across government and society. The marketplace for geographic data is a network of government and commercial suppliers, value-added intermediaries, and users. Within this marketplace, the diversity of products and services is increasing and two dominant business models have emerged: all rights are sold to the purchaser but the vendor retains the right to use the work, or rights are retained by the vendor but customers are allowed to use the data under a license. Licensing has become increasingly common since the early 1990s, and secondary and tertiary users worry that licensing will restrict the availability of government data to them. Commercial firms worry about having to compete with government producers. The next chapter describes multiple perspectives on the role and value of licensing.

|

50 |

Examples of the value-added dimension include access 24 hours a day and 7 days a week, specialized content, Web services, and reselling opportunities. The latter opportunities arise because presenting a view involves selecting and arranging information in a way that may give rise to “original expression” and thus, arguably, it is subject to copyright protection (see Chapter 5, Section 5.2.1). These opportunities only arise at the state and local levels, since federal agencies may not assert copyright ownership in works it develops (17 U.S.C. § 105). |

VIGNETTE C.

A SMALL BUSINESS PERSON'S DREAM

Samantha Adams runs a small business that combines information from multiple online sources to sell either as a new product or as a service to her regular customers. She is currently creating a new digital product called “My City After Dark” that includes detailed information about restaurants, entertainment establishments, and other late-night shopping. The product also includes a ghost-story walking tour of the city.

To create her product, Ms. Adams must affirmatively know that she has a legal right to incorporate the digital work products of others. Fortunately, in the new online environment, there is no need to negotiate terms of use when downloading a file. For example, Ms. Adams downloads and uses a land parcel map of the city after learning from the accompanying descriptive data (“metadata”) that the local government has dedicated the data file to the public domain. She downloads portions of a restaurant directory whose metadata indicates that information may be incorporated into other products at a standard fee per item. She rejects using several comparable directories for which no metadata on use conditions is provided or for which the fees or standard use terms in the license are less favorable. She downloads several "spooky music" files that can be used for free if attribution is provided. Most of the other content Ms. Adams photographs herself or gathers from historical sources in her local public library.

The complete “My City After Dark” file is delivered back to the Web along with its metadata and licensing terms. The file and future updates may be downloaded for a stated fee by anyone, including users of personal communicators—personal mobile devices incorporating phone, e-mail, video, Web access, data processing, and location communication capabilities along with high-volume data storage. Thousands of small businesses like Samantha Adams’ are now able to create similar new products or enhanced services because they can easily discover the ownership status and licensing conditions of location-based and related datasets found on the Web.

Ms. Adams’ dream is one of efficient discovery, comparison, and selection of data access and use conditions. She believes that it could come closer to reality by making standardized licensing and metadata creation capabilities available to all on the Web.