Chapter 2

Measurement

DEFINITION AND OVERARCHING THEMES

The aim of the cross-cutting session on measurement was to identify strategies communities might pursue for using performance measures to assess and improve quality of care, further the accountability of health care organizations, and inform payer and consumer purchasing and decision making. All of the communities participating in the summit had been involved in measuring the effectiveness of their efforts, although their objectives—whether for quality improvement purposes or public reporting—may have differed. Measurement was also an underlying assumption for all the condition-specific action plans.

The following definition of measurement served as the springboard for discussion during this session and had the general approval of the session’s participants (IOM, 2002):

To use quantitative indicators to identify the degree to which providers are delivering care that is consistent with standards or acceptable to customers of the delivery system. Performance measures may be used to support internal assessment and improvement, to further health care organization accountability, and to inform consumer and payer selection and purchasing based on performance.

KEY STRATEGIES

Overall, the participants view measurement as crucial to accelerating performance improvement in health care. Four key strategies emerged from this session: (1) integrate measurement into the delivery of care to benefit the patient whose care is measured, (2) improve information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure to reduce the burden of data collection, (3) focus on longitudinal change in performance and patient-centered outcomes in addition to point-in-time measures, and (4) improve public reporting by effectively disseminating results to diverse audiences.

Integrate Measurement into the Delivery of Care

The underlying principle behind this strategy is that measurement should be integrated into routine clinical practice, so that the process of providing care also enables measurement to occur. Decreasing the burden of measurement and increasing the likelihood of data collection makes it possible to determine more accurately the quality of care being delivered. Once the necessary data are available, health care delivery systems can develop creative solutions to address suboptimal performance—thus continually improving the process of care.

In addition to posing a minimal data collection burden, performance measurement and reporting cannot be overly time-consuming or perceived as punitive. Moreover, as noted throughout the condition-specific working group sessions, national consensus on a core set of performance measures should simplify and bolster compliance with data collection by eliminating the collection of multiple conflicting measures collected against competing or conflicting standards. It was suggested that this common set of measures would include assessment of success in meeting the Quality Chasm’s six aims for care—safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable—and do so in the most parsimonious manner possible so as to not be overwhelming (IOM, 2001). These key measures should be reviewed by professional societies and made readily available to purchasers and consumers.

|

“Institutional survival is not an aim of American health care. Patient well-being is the aim of American health care. Endorse the aims (IOM six aims) for improvement in measurable terms, and link it to measurement. If you don’t know how you are doing you can’t get better.” —Don Berwick, summit keynote speaker |

The Washington State Diabetes Collaborative—one of the 15 community participants at the summit—candidly shared with the participants in the measurement session some lessons learned from that initiative regarding the need for standardized data collection of a discrete set of measures. See Box 2-1 for a brief overview of this ground-breaking state-level project.

|

Box 2-1. The Washington State Diabetes Collaborative was established in 1999 to address the findings of a statewide project that identified significant gaps between existing and desirable diabetes care. Based on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series approach, this first state-level collaborative on chronic disease has engaged more than 65 teams from urban and rural, public and private, and small to large care delivery systems and health plans in improving the delivery of patient-centered diabetes care. Given the voluntary nature of the project—there were no external incentives for practitioners and facilities to participate—it was challenging at first to mandate a core set of measures to be collected, particularly across such a diverse set of stakeholders. As a result, during the first phase of the collaborative, considerable flexibility was allowed regarding what measures the team would use to assess progress related to glycemic control and blood pressure control. Although this flexibility was useful in that it permitted individual teams to follow their own internal quality improvement approach, it made meaningful comparisons or establishment of benchmarks difficult. Adjustments were made during the second phase of the project, and teams were required to track the same four measures: HbA1c <9.5 percent, LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol <130 mg/dl, blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg, and a documented self-management goal. With these standardized measures, it became possible to aggregate data more easily so the initiative could be evaluated as a whole. Overall, teams demonstrated improvement on these four measures, with higher gains in process-related than in outcome-related measures. Note: A more detailed description of this collaborative and related case studies can be found in the February 2004 issue of the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety (Daniel et al., 2004a,b). |

The asthma working group suggested that national organizations such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Leapfrog Group, the National Quality Forum (NQF), accrediting agencies, and appropriate subspecialty providers agree on a defined, well-validated set of quality performance measurement tools for chronic diseases—including patient self-management indicators—within 3 years. The depression and pain control working groups called on the NQF to serve as a convening body to bring together the appropriate experts to establish metrics for effective and efficient care in these areas. Many of the national champions at the summit weighed in on this issue and offered their support. Box 2-2 provides a snapshot of some of the commitments they made.

Improve Clinical ICT Infrastructure

Improving ICT infrastructure was identified as a key strategy to ease the burden of incorporating data collection, performance measurement, and results reporting into everyday clinical practice. Physician offices, hospitals, nursing homes, and health centers will require incentives to encourage the adoption of interoperable clinical information systems. A strategy suggested during this session was to reward practices that have clinical information systems in place—such as patient registries or partial/full electronic health records—that are used to collect data on their patient populations for quality measurement and improvement purposes. To this end, structural measures of ICT adoption by individual providers would have to be collected and reported.

|

Box 2-2. Steven Jencks, M.D., Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services “I want to be clear that CMS will work with you and other national partners and with the National Quality Forum to identify and implement a uniform standard national measure set involving the conditions discussed.” Arnold Milstein, M.D., Pacific Business Group on Health “Within the two national purchaser organizations in whose leadership I participate, the Leapfrog Group and the Disclosure Project, I commit to accelerating national consensus on, and public reporting of, measures of quality, efficiency, and care redesign at multiple levels, including individual physician office teams, hospitals, larger health care organizations, and communities.” Greg Pawlson, M.D., National Committee for Quality Assurance “We’ve been working already with the American Medical Association Consortium, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the American Stroke Association, CMS, Leapfrog, the Pacific Business Group on Health, and many others to really try to populate the full spectrum of performance measures related to all six aims of the Institute of Medicine, and also to reduce duplication and redundancy.” |

Once this structural change occurs, measuring performance for multiple conditions can readily be achieved. Box 2-3 describes the Bridges to Excellence initiative, which recently launched a program to incentivize structural change in clinical ICT capability in physician offices.

Although incentives to build ICT capacity are certainly important, they are only a piece of a complex puzzle. Unresolved issues related to interoperability standards (addressed in detail in Chapter 3) and consensus on measures also figure prominently. There is a critical need for investment in this area, and participants called for the federal government to provide the necessary leadership. The federal government has provided grants to state mental health and substance abuse agencies to embark upon this effort, but limited resources impede the ability to reach all providers at the local level.

Participants generally believe that widespread adoption of ICT to assist measurement collection at the physician office level will necessitate partnering by public- and private-sector purchasers.

The condition-specific working groups also touched on the essential role of ICT in supporting measurement efforts. For example, recognized measurement experts in the asthma group affirmed that metrics for processes of care for asthma are well established. The major challenge now is moving these measures closer toward implementation. One hurdle is that these measures are based on patient reports and chart reviews, rather than on more easily accessible administrative data. Therefore, the asthma group suggested that the focus needs to be on (1) mandating/pressuring providers to collect these data and (2) creating the necessary

|

Box 2-3. Bridges to Excellence—a coalition of employers, physicians, health plans, and patients—is a program designed to improve the quality of care by acknowledging and rewarding health care providers that have taken significant steps to build new structural capability and achieve high performance levels to further the Quality Chasm’s six aims of safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, and equity. Initially, this effort will target three areas—diabetes care, cardiovascular care, and the structure of care management systems—all of which were highlighted during the summit. One initiative currently under way is the Physician Office Link, which allows physician practices to earn bonuses for implementing structural changes to increase quality, such as investing in ICT and care management tools. These changes include electronic prescribing to reduce medication errors, electronic health records embedded with guideline-based prompts/reminders, disease registries and management programs for patients with chronic conditions, and patient educational resources available in multiple languages. Additionally, a report card for each physician office assessing structural capability in these areas will be issued and made available to the public. Note: A more detailed description of Bridges to Excellence programs may be found at their website (Bridges to Excellence, 2004). |

ICT infrastructure so the data can be collected more easily.

The depression working group identified ICT as the basis for all transformation and for all of their proposed solutions. They acknowledged that, given concerns about privacy and stigma, it will be challenging to incorporate behavioral health information into electronic health records. The working group suggested that behavioral health data should be treated in the same way as all other health information, consistent with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (U.S. DHHS, 2004). The group presented a strategy with the initial 1-year goal of convening a group of 15 communities that would include all of the key stakeholders and defining a shared dataset for behavioral health in primary care. This first year would see pilot collection of these data and conclude with the formulation of recommendations for a national behavioral health data policy. Over the course of 3 years, this effort would be expanded to include a broader base of community agencies and stakeholders. The process for the 3-year goals would mirror that for the 1-year pilot, with an expanded group of participants.

|

“The absence of electronic health records limits the ability to deploy performance measures and gather data. It’s a severe limitation. People want to know why we don’t approve more performance measures. It’s simply unaffordable when you’re collecting data by hand. Electronic health records become critically important because they make it possible to gather performance data as a by-product of the care delivery process.” —Dennis O’Leary, summit participant |

Focus on Longitudinal Change in Performance and Patient-Focused Outcomes

Another solution put forward by the strategy session participants was for measurement efforts to focus on longitudinal change in patient health status over time. Implementing this solution would require evolving from the customary collection of process and outcome measures—which tend to focus on provider inputs—to a more multidimensional approach that includes assessing patients’ self-reports on their capabilities for self-management and their functional status. Using patient-reported health status to inform the medical encounter, essentially making it part of the “vital signs” taken at any visit, would improve individual patient care, as well as enhance the ability to gauge on a population basis how well care is being delivered for specific conditions and patient subgroups with each condition. A case in point provided during the session was the use of a standardized questionnaire to evaluate heart failure status. This type of feedback could quite easily be obtained from patients while they are sitting in the waiting room, and providers could use this information to customize and improve care. Additionally, data could be plotted over time to track patient-reported progress and/or aggregated to support population-based comparisons.

The heart failure working group also suggested collecting patient-reported health status as a routine part of care. They emphasized the need for adopting multiple approaches to make the collection of information from patients more convenient—such as a computer in the waiting room and web-based entry from home—as well as for organizing the data for clinicians in an easily interpretable format. Such information should be made readily available to the physician/nurse at first contact during the office visit and be automatically incorporated into the patient’s electronic health record if entered at home—coupled with an alarm to the health provider if there is a negative change in status. Additionally, patients should be provided with

their “scores,” and these results should be graphed over time to assist patients in self-management of their condition and allow the provider to examine trends. The group proposed that measures of mental health status also be included and that comorbidities be considered in interpreting quality-of-life scores, as heart failure patients often have multiple chronic illnesses, such as depression and diabetes.

The pain control working group proposed making assessment of pain the “fifth vital sign” and suggested that measures be developed to track and monitor the following: (1) percent of patients being evaluated for pain, (2) interventions conducted, and (3) effectiveness of the interventions (rate of overall decline in pain). These measures would then be incorporated into the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) annual National Health Care Quality Report (AHRQ, 2003) and the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) report (NCQA, 2004).

The group also proposed taking a patient-centered approach to measuring pain control. Strategies to achieve this goal include (1) providing cancer patients with multiple ways to record their pain outside the clinician encounter, such as over the Internet or by phone, so that results can be reviewed regularly and acted on in a timely way; and (2) establishing measures of family/caregiver experience as part of a performance measures set, for example, adding a question to the death certificate—which is often completed by a caregiver/family member—asking how effective the care team was in treating end-of-life pain.

Agreeing with the strategy session participants, the pain working group recognized the need to evaluate data on the prevalence of pain over time for individual patients. Doing so is particularly important during transitions between settings, such as from hospital to nursing home, when breakdowns in care are most likely to occur. The group suggested that providers adopt a standardized patient flow chart that would be recorded electronically for purposes of quality improvement, performance measurement, and patient education.

Improve Public Reporting by Disseminating Results to Diverse Audiences

This strategy had two prongs: first, to improve public reporting of performance measures by including the patient experience; and second, to package and disseminate this information in a way that is useful and meaningful to different audiences. Underlying assumptions brought forth by the working groups included the need for transparent public reporting and the use of this information to foster quality improvement at multiple levels of the health care delivery system. For example, patients could compare their diabetes outcomes against those of a similar cohort as a stimulus to their self-management, individual clinicians could judge their performance among their peers, and communities could correlate local outcomes with regional and/or national benchmarks.

In response to the first part of this strategy, the condition-specific working groups echoed the need for patient/consumer input in the development and selection of quality measures. The depression working group suggested several strategies to this end: obtaining feedback from objective patient advocates and consumers; conducting focus groups among patients with depression to identify key quality characteristics and outcomes of care; and rallying a collaborative group of stakeholders—patients, physicians, purchasers, and payers—to achieve consensus on performance and satisfaction measures.

The second part of this strategy—reporting measures at different levels of granularity and in a variety of formats to divergent groups—is critical to stimulating consumer demand for quality services and accelerating the uptake of best practices by providers. The asthma

working group called for identifying methods to increase consumer use of report cards and for determining how various population subgroups prefer to receive these materials. Intermountain Health Care’s Depression in Primary Care Initiative illustrates how performance data can be used and marketed to address the needs of a variety of stakeholder groups (see Box 2-4).

|

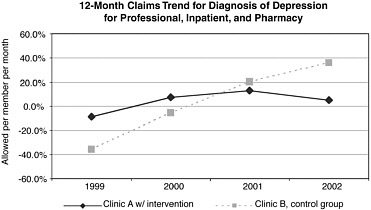

Box 2-4. Intermountain Health Care––an integrated delivery system that includes providers, plans, and hospitals––has implemented a Depression in Primary Care Initiative that provides patients and their families with the tools and organizational supports needed to identify, diagnose, treat, and manage depression. Designed to impact the entire health care system, this quality improvement process employs integrated mental health teams that are made available to primary care practices. In an effort to create a sustainable business case that links financial value to improved clinical outcomes, the program measures and evaluates progress in three areas:

Data for these three outcome areas are used to engage multiple stakeholders—insurance plans, employers, physicians, mental health specialists, support staff, and patients—and are presented in a “language” that each of these groups understands. An example given at the summit was providing claims data to health plans in a quickly interpretable format. The graph below demonstrates cost savings over a 4-year period for Clinic A, which received the intervention and whose cost trends were stable over time, as compared with the increased costs for a control group (Clinic B) with a similar case mix that did not receive the intervention. These data allowed health plans not only to see potential savings, but also to build a business case to finance and sustain this initiative. |

SOURCE: Reprinted with permission from Brenda Reiss-Brennan (2004). Copyright 2004 by Brenda Reiss-Brennan. |

CLOSING STATEMENT

At the summit, measurement was repeatedly identified as the backbone of quality improvement efforts. From the need to measure outcomes to make a business case and link rewards to quality care (see Chapter 6) to the importance of community-based measures and outcomes (see Chapter 7), documenting performance is critical to substantiate the positive effect of interventions—such as care coordination and self-management—and to better direct resources to problem areas.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2003. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: AHRQ.

Bridges to Excellence. 2004. Bridges to Excellence: Rewarding Quality across the Health Care System. [Online]. Available: http://www.bridgestoexcellence.org/bte/ [accessed April 29, 2004].

Daniel DM, Norman J, Davis C, Lee H, Hindmarsh MF, McCulloch DK, Wagner EH, Sugarman JR. 2004a. Case studies from two collaboratives on diabetes in Washington state. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety 30(2):103–108.

Daniel DM, Norman J, Davis C, Lee H, Hindmarsh MF, McCulloch DK, Wagner EH, Sugarman JR. 2004b. A state-level application of the chronic illness breakthrough series: Results from two collaboratives on diabetes in Washington state. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety 30(2):69–79.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2002. Leadership by Example: Coordinating Government Roles in Improving Health Care Quality. Corrigan JM, Eden J, Smith BM, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

NCQA (National Committee for Quality Assurance). 2004. NCQA: National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncqa.org/index.asp [accessed March 24, 2004].

Reiss-Brennan, B. 2004 (January 6). Quality Chasm Summit. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit, Washington, DC. Institute of Medicine Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm.

U.S. DHHS (United States Department of Health and Human Services). 2004. HHS—Office for Civil Rights—HIPAA. [Online]. Available: http://www.os.dhhs.gov/ocr/hipaa/ [accessed March 24, 2004].