Chapter 3

Information and Communications Technology

DEFINITION AND OVERARCHING THEMES

The focus of the cross-cutting strategy session on information and communications technology (ICT) was to identify ways that communities can enhance their health care information infrastructure to improve care—including advances in Internet-based communication, electronic health records (EHRs) for small practices, patient registries, and medication order entry systems, among others. To set parameters for this rather broad topic, the following definition of ICT was agreed upon by session participants and served as the starting point for discussion (IOM, 2002, 2003a):

To use information and communications technology––both within and across organizations—to improve quality and safety; enhance access; and reduce waste, delays, and administrative costs. Attributes of an ICT infrastructure include web-based communication; real-time access to electronic patient information (eventually captured in an EHR system); easy access to reliable science-based information; computer-aided decision support tools, such as medication order entry systems; and the ability to capture patient safety information for use in designing ever-safer delivery systems. Such an infrastructure should include a focus on multiple dimensions, including providers, individual health, and population health.

The importance of ICT in both supporting and sustaining quality improvement efforts was a recurring theme throughout the summit. From providing a platform for the exchange of patient information across multiple providers to helping patients in the self-management of their condition, ICT was identified as an enabling force to accelerate system interventions designed to improve care for individuals with chronic conditions. Specifically, participants in the ICT session proposed strategies

directed at both the micro and macro levels, with the ultimate goal of having EHRs in physicians’ offices in every community and a transportable health record available to every patient.

KEY STRATEGIES

The session participants proposed three strategies for overcoming barriers to successful integration of ICT into the delivery of care: (1) use standardized systems, (2) provide federal leadership to accelerate the adoption of EHRs, and (3) create a public utility that holds data at the local level.

Use Standardized Systems

There was a resounding call for national data standards during the ICT session, accompanied by an expression of frustration with the current inability to transmit health information across organizational and regional boundaries. Participants voiced a strong sense of urgency to the initiation of change, suggesting that any delay in the adoption of standards would exacerbate or worsen the lack of interoperability that has hindered the spread of best practices and the exchange of patient information among providers. Thus as the number of “stand-alone” EHRs proliferates, it will only become more difficult for those who have tried to move forward despite this barrier to integrate systems in which they have invested such considerable resources into standards-based data storage and communication systems that may or may not be compatible with those existing systems.

Standards are also the building blocks for an ICT infrastructure that enables patient health information to be shared at the point of care (IOM, 2003a). By having this information readily available at the time of care delivery—along with computerized reminders for preventive services—clinicians are better able to provide the right care at the right time to their patients (Balas et al., 2000). The ICT-enhanced program of Madigan Army Medical Center (MAMC) illustrates the critical need for national data standards to provide this type of decision support up front, not after the fact, and to facilitate the diffusion of effective programs, such as MAMC’s diabetes initiative (see Box 3-1).

|

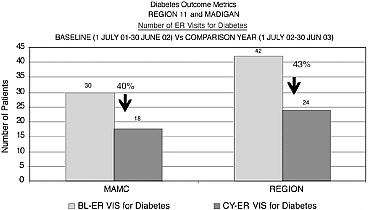

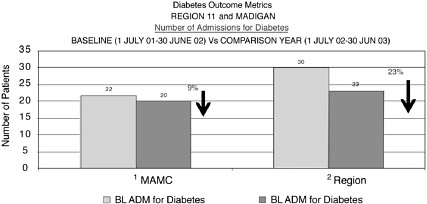

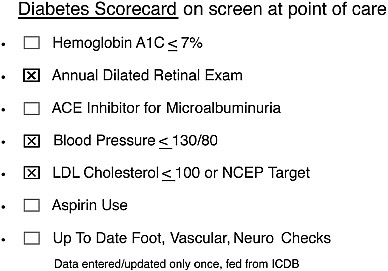

Box 3-1. Madigan Army Medical Center (MAMC) is a tertiary care academic medical center with approximately 250 staff and residents who support all Department of Defense direct health care in the Pacific Northwest region. In the community served by MAMC, 76,000 beneficiaries are enrolled in primary care, including 3,000 patients with adult onset diabetes. MAMC also is a purchaser of health care services under the TRICARE program, covering tertiary care for 460,000 beneficiaries in Washington, Oregon, and Alaska. MAMC has launched an initiative to improve the quality of care for diabetics within its targeted population. This initiative includes an emphasis on “preventive maintenance” and the use of ICT to provide decision support for clinicians and actively engage patients. The centerpiece of the program is an electronic scorecard keyed to evidence-based Diabetes Quality Improvement Program (DQIP) measures and populated automatically from the laboratory, the pharmacy, and other clinical |

|

data systems. At the point of care, clinician and patient review the results from the scorecard together and use them to make collaborative decisions about the next steps in the care plan. Below is a sample scorecard, which demonstrates that an annual eye exam and blood pressure and LDL cholesterol testing have been completed; however, hemoglobin A1c, ACE Inhibitor, aspirin use, and up-to-date foot exam are still outstanding on this sample patient. As a result of this interactive tracking and monitoring of patient outcomes, decreases in emergency department visits and hospital admissions of 40 and 9 percent, respectively, have been realized. Charts 1 and 2 below present the outcomes of the data discussed above. Brigadier General Michael Dunn, representing the MAMC diabetes initiative, shared with the participants in this session that for the 3,000 diabetics within his controlled primary care population, this tool enabled him to provide a very high standard of evidence-based care. In the TRICARE network, however, he could not easily duplicate this effort, as there are at least 20 incompatible EHRs among his different provider organizations, and none of these systems are able to “talk” to each other.  |

Provide Federal Leadership to Accelerate the Adoption of EHRs

The ICT session emphasized the need for the federal government to provide leadership in four areas: (1) promulgating national data standards for the transfer of electronic health data, (2) setting rules and regulations for the use of EHRs, (3) increasing consumer awareness of the importance of these tools, and (4) financing EHRs.

Promulgating National Data Standards

Like participants in the ICT session, the IOM committee that authored the report Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care called upon the federal government to be a major driver in establishing and disseminating national data standards (IOM, 2003a). Specifically, the committee recommended that Congress provide direction and financial support to the Department of Health and Human Services, the Consolidated Health Informatics Initiative, the National Committee on Vital Health Statistics, AHRQ, and the National Library of Medicine to further this effort. As in the other cross-cutting sessions, there was general consensus that a public–private partnership is essential to accomplish this goal—whether by conducting demonstrations of paying for performance, developing a core set of standardized measures, or instituting flexibility in delivery of care through waiver programs.

Many of the national champions at the summit are actively engaged in joint ventures to improve and promote data standardization. For example, the American Hospital Association was instrumental in establishing the National Alliance for Health Information Technology, a public–private partnership addressing standards for EHRs and medication bar coding. Members of the alliance are from multiple health care sectors and represent hospitals, health systems, medical groups, technology companies/vendors, public and private payers, the pharmaceutical industry, and other standards-setting groups (NAHIT, 2004).

The asthma working group reiterated the need for a multistakeholder approach to resolving the problem of data standardization. They suggested that this approach could be applied practically, for example, first to an electronic personal health summary and then progressing rapidly, but incrementally, toward a uniform EHR. They called specifically for a coalition of health plans, CMS, consumer groups, organized medicine, and other health care providers to facilitate the adoption of a standardized personal health record summary whose format would allow for the transfer of clinical data to any computer system or EHR, as well as a hard-copy report in a readable format for paper transfer.

The heart failure working group proposed that patients be able to carry their health records in some type of easily transportable electronic format, such as a thumb memory stick or “smart card.” They suggested this as a way of empowering patients to monitor their status from home and enabling them to transfer their health information back to their case manager electronically. The Continuity of Care Record initiative, about to be put into practice, is one such effort that will bring patients one step closer to a portable personal health record that can easily be transferred electronically (see Box 3-2).

During his keynote speech, Don Berwick called for patients’ unfettered access to their health records—“no cost, no barriers, no limitations”—and pointed to the patient-carried record as an attainable first step. Accomplishing this goal, he argued, is an essential precondition to making the patient the source of control, and fulfills the requirements of the third of 10 rules set forth in the Quality Chasm report for redesigning health care processes1 (IOM, 2001:8).

|

Box 3-2. The Continuity of Care Record (CCR) is an XML document standard that will enable a core set of relevant patient information to be transported easily across health care settings and providers. The rationale behind the development of the CCR was to standardize data—not software or computer systems—so that personal health information can readily be displayed on any computer, thus avoiding proprietary barriers to progress in this area in the past. The CCR may be viewed by a web browser, a PDF reader, or a word processor. Key components of the CCR include patient health status (diagnoses, allergies, and vital signs), care plan, patient and provider identifiers, and insurance information. The CCR has the potential to enhance care coordination, particularly during referrals, transfers, and discharges. For example, its use might make it possible to circumvent duplicate laboratory tests, drug interactions, and misdiagnoses attributable to incomplete or missing health records. Additionally, the CCR could serve as a personal health record, helping patients in the self-management of their care. The CCR is a collaborative effort among ASTM International, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Health Information Management and Systems Society, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association, and the Patient Safety Institute. Roll-out of this first interoperability standard is slated for mid-June 2004. Note: For additional information, contact the ASTM International Technical Committee on Healthcare Informatics (staff manager Dan Smith) at their website (Committee E31 on Healthcare Informatics, 2004). |

|

My own prescription is to give every patient in Flint, Michigan, their medical records, end of story, tomorrow.” —Don Berwick, summit keynote speaker |

Setting Rules and Regulations for the Use of EHRs

In May 2003, the Department of Health and Human Services requested that the IOM provide guidance on a set of “basic functionalities”—defined as key care delivery–related capabilities—that an EHR should possess. It was reasoned that consensus around a minimal set of expectations would smooth the progress and accelerate more widespread adoption of EHRs. The IOM committee that undertook this task identified eight core functions for an EHR: (1) health information and data, (2) results management, (3) order entry/management, (4) decision support, (5) electronic communication and connectivity, (6) patient support, (7) administrative support reporting, and (8) population health management (IOM, 2003b). The next step is for these elements to be incorporated into an EHR functional model developed by Health Level 7 (HL7), a leading standards-setting organization (Health Level 7, 2004). Presently, CMS is in the HL7 balloting stage for approval, but given the vast stakeholder interests involved, more debate is likely to ensue around this topic (Personal communication, D. Brailer, Health Technology Center, March 17, 2004).

Increasing Consumer Awareness of the Importance of These Tools

The participants focused on ways in which the government, as well as others, could induce consumer demand for quality services directly linked to the use of ICT. The challenge is to convince consumers that they should be deeply alarmed about the current state of health care quality in the first place. To this end, quality will need to be defined in a way and in terms that are meaningful to consumers as opposed to the current situation, in which consumers seldom seek out performance information on hospitals, providers, or health care organizations becasue they mistrust or do not understand the data (FACCT, 1997; Marshall et al., 2000; Shaller et al., 2003). Strategies discussed during the session included continuing to educate consumers about medical errors, demonstrating ICT solutions that involve consumers in their care, and making quality reporting that arises from this technology available to consumers. In short, the connection between ICT and quality needs to be obvious to consumers, and most important, ICT must be seen as an indispensable tool for improving care.

Financing EHRs

During the summit, extensive attention was given to financial incentives—from both public and private sources—as a mechanism to encourage evidence-based practices and system-level changes that are known to improve the quality of care, particularly the deployment of EHRs. (See Chapter 6 for a detailed overview, as well as the other cross-cutting chapters that weave this concept into their proposed solutions). In this section, as was the case during the ICT sessions, the focus is on how to promote and stimulate the acquisition and use of EHRs by physicians, taking into consideration both the costs and the perceived benefits that impact their adoption. Although time constraints did not permit an extensive discussion of the many factors influencing clinician uptake of ICT, three key elements were discussed by the participants: (1) demonstrating a scientific foundation for the use of ICT, (2) minimizing adverse effects on workflow, and (3) providing a return on investment (Miller and Sim, 2004).

To justify the expense and time commitment required to integrate EHRs into their practice setting, clinicians require empirical evidence that such interventions as computerized physician order entry actually do decrease the potential for adverse drug events, or that electronic prompts reminding them to order

screening tests to monitor chronic conditions can help avoid long-term complications (Bates et al., 1999; Casalino et al., 2003; Kaushal et al., 2001). Clinicians must be assured that EHRs will not add to an already heavy workload, and that ICT will ultimately help them deliver safer and more effective care to their patients. Additionally, although the evidence base is growing, financial support for EHRs by Medicare and health plans has been slowed in part by minimal scientific evidence to date that they are efficacious and effective.

Underlying all these obstacles is the need to develop a business case for investing in ICT infrastructure at both the clinician and organization levels. As discussed in Chapter 6, incentives need to be provided to those who will incur the cost of setting up and maintaining these systems, as most of the benefits currently tend to flow to other stakeholders (Hersh, 2002).

Create a Public Utility That Holds Data at the Local Level

Presently, electronic health data are often considered a private resource, benefiting primarily organizations in their internal quality improvement efforts. Participants in the ICT session suggested framing health data as a public good and creating a public utility that would hold the data, making them accessible at the community level. The County of Santa Cruz, California, a summit community, is moving in this direction with its diabetes initiative, currently under way (see Box 3-3).

In the past few years, regional initiatives in Santa Barbara, California, and Indianapolis, Indiana, have established infrastructure for the exchange of health information among physicians, patients, hospitals, and ancillary care facilities. Although both of these efforts are unusual in their origins—both emerged from substantial field research efforts that were adopted by local health system leaders—more than 50 communities and regions are now planning regional health information exchange efforts. While early, these efforts in a diverse range of communities evidence a common response to the broad problem of fragmentation of care across physicians and among health plans and employers, which hampers efficiency and limits patients’ control over their care delivery.

These regional projects use a variety of technical solutions, but all are based on three core principles: (1) identified health information is ultimately controlled by the patient; (2) current medical data controls are inadequate, and data loss, theft, and misuse are common vulnerabilities of paper systems; and (3) common infrastructure lowers technical and administrative costs. These initiatives share a vision for improving clinical care and health status that will be realized through broader access to health data at the point of care when the data are needed. Such efforts are being analyzed closely to determine feasibility for widespread use in the United States (Brailer et al., 2003).

CLOSING STATEMENT

Most participants in the summit agreed that few innovations in health care delivery are as promising as ICT, and most acknowledged the substantial obstacles that have prevented these technologies from becoming standards of care. Every community project described by participants identified a set of disease-specific interventions that would be easier, more effective, or less expensive to implement if a functioning ICT infrastructure were in place. The broad dissemination of ICT as a patient care tool is a key step to realizing long-standing goals for consumer well-being, public health, and the health care industry.

|

Box 3-3. Santa Cruz County, California, a blend of urban and rural communities with a population of 260,000, has an estimated prevalence of diabetes of approximately 7 percent, affecting the lives of more than 18,000 people. To address this problem, two competing private medical groups and the Medi-Cal managed care program have joined the public health department in two initiatives—the Regional Diabetes Collaborative and the Santa Cruz Health Improvement Partnership—that bring together front-line professionals from all disciplines and executives to reach consensus on common-ground issues. To date, a web-based decision support system for comprehensive diabetes care has been developed that integrates claims data, laboratory results, pharmacy data, and information generated during office visits. The database, located on the server in physicians’ offices scattered throughout the county, allows them to review the data on line (or on a paper printout if preferred) and compare them against their patients’ diabetes care parameters, such as hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol levels. Additionally, “action prompts” and an up-to-date list of needed services are generated electronically, serving as a monitoring tool for both the clinician and office support staff. Currently under development is a uniform format for a “dashboard”—a screen that comes up on the computer showing the patient’s diabetes-related indicators—to be used across multiple systems. Thus when patients go from one system to another, their information will be presented and collected in a consistent way, regardless of where they are receiving care. Future plans are to offer this program to community clinics, public health department clinics, and emergency departments in the county, ideally making it a public utility. Wells Shoemaker, representing the County of Santa Cruz initiatives at the summit, identified four success factors, based on the county’s experiences, in incorporating ICT in care processes: (1) providing decision support at the point of care; (2) concentrating on population management, particularly underuse of preventive services; (3) giving feedback and recognition to clinicians who are high performers; and (4) migrating successful strategies to practices that are struggling. |

REFERENCES

Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD. 2000. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine 160(3):301–308.

Bates DW, Teich JM, Lee J, Seger D, Kuperman GJ, Ma’Luf N, Boyle D, Leape L. 1999. The impact of computerized physician order entry on medication error prevention. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 6 (4):313–321.

Brailer DJ, Augustinos N, Evans LM, Karp S. 2003. Moving toward Electronic Health Information Exchange: Interim Report on the Santa Barbara County Data Exchange. Oakland, CA: California HealthCare Foundation.

Casalino L, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Schmittdiel JA, Bodenheimer T, Robinson JC, Rundall T, Oswald N, Schauffler H, Wang MC. 2003. External incentives, information technology, and organized processes to improve health care quality for patients with chronic diseases. The Journal of the American Medical Association 289(4):434–441.

Committee E31 on Healthcare Informatics. E31. [Online]. Available: http://www.astm.org/cgi-bin/SoftCart.exe/commit/committee/E31.htm?E+mystore [accessed May 10, 2004].

Dunn, M. 2004. (January 6). Madigan Army Medical Center. Presentation at the Institute of Medicine 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit, Washington, DC. Institute of Medicine Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm.

FACCT (Foundation for Accountability). 1997. Reporting Quality Information to Consumers. Portland, OR: FACCT.

Health Level Seven. Health Level Seven, Inc.. [Online]. Available: http://www.hl7.org/ [accessed March 25, 2004].

Hersh WR. 2002. Medical informatics: Improving health care through information. The Journal of the American Medical Association 288 (16):1955–1958.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2002. Fostering Rapid Advances in Health Care: Learning from System Demonstrations. Corrigan JM, Greiner AC, Erickson SM, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003a. Patient Safety: Achieving a New Standard for Care. Aspden P, Corrigan JM, Wolcott J, Erickson SM, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2003b. Key Capabilities of an Electronic Health Record System: Letter Report. eds. Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Kaushal R, Barker KN, Bates DW. 2001. How can information technology improve patient safety and reduce medication errors in children’s health care? Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 155(9):1002–1007.

Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. 2000. The public release of performance data: What do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. The Journal of the American Medical Association 283(14):1866–1874.

Miller RH, Sim I. 2004. Physicians’ use of electronic medical records: Barriers and solutions. Health Affairs (Millwood, VA) 23 (2):116–126.

Shaller D, Sofaer S, Findlay SD, Hibbard JH, Delbanco S. 2003. Perspective: Consumers and quality-driven health care: A call to action. Health Affairs (Millwood, VA) 22(2):95–101.

NAHIT (The National Alliance for Health Information Technology). 2004. Creating a Leadership Legacy. [Online]. Available: http://www.nahit.org [accessed March 25, 2004].