4

Emerging Roles in Experimentation—The Joint Connection

All recent U.S. military operations have been joint, and nearly all future operations will likely be so as well. Hence, naval concept development and experimentation should be done in a joint context, although there are naval-unique capabilities that must also be developed at the same time. One challenge for the Naval Services is to establish the proper balance between the joint and naval-specific activities.

This balance is by no means static. Indeed it has been undergoing profound shifts in the last few years as both the Department of the Navy and the entire Department of Defense have rethought and reworked their experimentation efforts. While most of the committee’s data gathering drew to a close during the summer of 2002, it believes that fundamental lessons for experimentation can be discerned even as this evolution in experimentation continues in the Department of the Navy and the Department of Defense.

Overall, three distinct venues for joint experimentation present themselves today: within the U.S. Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) experimentation process, within the regional Combatant Commands in the field, and through cross-Service experimentation, in which another Service participates in a predominantly naval experiment or vice versa. This chapter discusses each of these venues and provides a set of basic principles for striking an appropriate balance between joint and naval-specific experimentation.

U.S. JOINT FORCES COMMAND AND ITS EVOLVING MISSION

Today’s U.S. Joint Forces Command was foreshadowed by the U.S. Readiness Command in the 1970s and 1980s, which then had the mission of developing joint doctrine and evaluating joint readiness through joint exercises and other means. First a regional command, USJFCOM has lost geographical responsibilities and is now a functional unified command, primarily a force provider, joint force trainer, with additional responsibilities in joint requirements and interoperability. Since Congress specified in 1998 that the Secretary of Defense should designate a combatant commander to undertake joint warfighting experiments and has since directed the DOD to undertake specific “Joint field experiments,”1 USJFCOM now plays an important and growing but still changing role in military experimentation.

Historically, USJFCOM evolved from the United States Atlantic Command (USLANTCOM), which had long focused on defending the Atlantic Ocean and also on operations in the Caribbean.2 In recognition of the changing world environment, the mission of USLANTCOM was changed in 1993 to provide a more joint focus (and its acronym changed to USACOM). In particular, component commands from the Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force were added to the Navy component command already assigned, and USACOM was made responsible for training forces from all four Services for joint operations. USACOM would then supply ready joint forces to other unified commands anywhere in the world, while still maintaining its responsibilities in the Atlantic and the Caribbean.

In 1999, the U.S. Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) was created from USACOM. It retained the responsibilities and Service component commands of USACOM but was given even greater joint focus, with new responsibility for joint force integration, experimentation, and doctrine development in addition to joint training. Then, so that USJFCOM could focus entirely on these functional responsibilities and on its role as a force provider, its geographic areas of responsibility were assigned to other unified commands in 2002.

Today, USJFCOM figures prominently in the work of defense transformation, including the development of joint concepts, the conduct of experiments, and the definition of joint requirements. In USJFCOM’s own statement of its vision, “U.S. Joint Forces Command leads the transformation of the United States

Armed Forces to achieve full spectrum dominance as described in Joint Vision 2020.”3

USJFCOM is the executive agent for joint warfighting experimentation. Its congressional mandate from the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year (FY) 2001 requires it to conduct “a Joint warfighting experimentation program” through “field experiments under realistic conditions across a full range of future challenges.”4 USJFCOM’s most recent response to this mandate was a large field event named Millennium Challenge ’02 (MC 02) discussed at length below. MC 02 was embedded in a larger experimentation context of war games, analyses, and limited-objective experiments (LOEs). As will be seen, this has proven a resource-intensive requirement in terms of people, operational units, and experimental infrastructure as well as equipment and funding.

USJFCOM’s evolution appears by no means to be at an end. In fact, its pace of change may be increasing as recent guidance from the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff leads to further changes in the ways in which USJFCOM plans and conducts experiments. The most relevant portions of this latest guidance read as follows:

-

As Executive Agent for joint experimentation, you will develop a Joint Experimentation Campaign Plan (JE CPLAN) that looks both inside and outside the Department of Defense for concepts and capabilities…. The plan must incorporate a decentralized process to explore and advance emerging joint operational concepts, proposed operational architectures, experimentation and exercise activities currently being conducted by the Joint Warfighting Capabilities Assessment Strategic Topic Task Forces, the combatant commands, the Services and Defense agencies. . . .

-

The development of a standing joint force headquarters (SJF HQ) prototype and the other tasks directed and outlined … remain the highest priority.

-

In coordination with the combatant commands, Services, Joint Staff and Defense agencies, include the following in USJFCOM’s JE CPLAN:

-

Rapid exploitation of ideas and innovations demonstrated in, and lessons learned from, the war on terrorism.

-

Concepts, capabilities and measures of effectiveness to conduct joint operations in an uncertain environment and complex terrain. Include for approval the concepts and capabilities for improvements in joint operation and command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (C4ISR) in urban terrain and jungle environments, and consider joint operations in mountainous or heavily forested environments. Apply special emphasis to the concepts in limited objective experiments and other events in FY 2004 and FY 2005.

-

|

3 |

GEN Henry H. Shelton, USA, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. 2000. Joint Vision 2020, The Pentagon, Washington, D.C., June, p. 13. Available online at <http://www.dtic.mil/jointvision/jv2020.doc>. Accessed October 7, 2003. |

|

4 |

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2001(P.L. 106-398, 114 Stat. 1654). |

-

Fast-deploying joint command and control structures that … [employ] reach-back….

-

Concepts to provide warfighters at all levels improved real-time battlespace awareness….

-

Joint capabilities enabling the near-simultaneous … deployment of air, land, sea, cyber, and space warfighting capabilities….

-

The transformational concepts and capabilities of the Nuclear Posture Review….

-

Current efforts to promote and develop regional component commander-sponsored joint and multinational experimentation and capability-based modeling and simulation partnerships.

-

It is important to ensure continued development of the concepts and ideas demonstrated during and emerging from Millennium Challenge 02….5

Roles and Capabilities of the U.S. Joint Forces Command

USJFCOM currently offers capabilities that support both experimentation and transformation. It will play an increasingly strong role in both in the future. Its main activities to these ends revolve around concept development, scheduling, experimentation, doctrine and training, and requirements definition, as briefly noted below.

-

Concept development. USJFCOM’s Joint Experimentation Directorate (J-9) organization is developing a number of new joint warfighting concepts with an emphasis on operational-level unified command and control. Many USJFCOM concepts in the knowledge-management area are broadly similar to those of the Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC), but most are still early in the concept-generation process. As a concrete measure of their present maturity, none of the concepts had been validated or accepted at the time of this study, and only about half had received an initial assessment as of mid-2002 when MC 02 was carried out.

-

Scheduling. USJFCOM conducts annual scheduling conferences that coordinate and synchronize deployments, exercises, and other major activities across the Services—including experimentation—in order to maximize the performance of the joint mission.

-

Experimentation. USJFCOM conducts a range of experiments, including the congressionally mandated joint series of Millennium Challenge exercise/ experiment. These joint “field experiments” are a combination of what this study

-

terms exercises and experiments that explore USJFCOM concepts. At the same time, these experiments may also explore Service-specific concepts, through the incorporation of Service events such as fleet battle experiments (FBEs) into the bigger joint experiment. Each joint experiment includes a lengthy planning cycle involving all of the Services. The NWDC and the USMC’s Joint Concept Development and Experimentation (JCDE) division work closely with the USJFCOM experimenters in the J-9 organization.

-

Doctrine and training. USJFCOM, through its Joint Warfighting Center (JWC), develops joint doctrine and trains all joint headquarters staffs in it. The JWC includes the Joint Training, Analysis, and Simulation Center (JTASC) for performing the training. The JTASC also contains USJFCOM’s Joint C4ISR Battle Center (JBC), chartered to lead the near-term transformation of USJFCOM’s C4ISR capability through assessment and experimentation with new technologies. The JBC identifies shortcomings in the combatant commanders’ C4ISR systems and provides near-term solutions. It also prepares DOTMLPF documentation to support the solutions.

-

Requirements. USJFCOM’s joint interoperability and integration (JI&I) process coordinates joint experimentation results to ensure that all DOTMLPF recommendations are integrated for consideration by the Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) and the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC).6 The JROC, composed of the vice chiefs of each Service under the vice chairman, appears to be gradually enlarging its mandate to include a role in the approval of joint concepts and perhaps experiments, in addition to its established role of approving requirements.

Current and Evolving U.S. Joint Forces Command Experimentation Programs

USJFCOM conducts many different types of experimentation activities, including war games, constructive simulations, human-in-the-loop simulations, limited objective experiments, and large-scale field exercises such as Millennium Challenge ’02. Table 4.1 presents USJFCOM’s experimentation activities through September 2002.

The active forces in these USJFCOM experiments, as well as large-end items such as equipment, headquarters, staffs, and so forth, are provided by the Services, which in general are performing their own Service-unique experiments simultaneously. The Services are directed to support, participate in, and fund a share of the joint experiment effort, over and above their own experiments.

TABLE 4.1 Experimentation Activities of U.S. Joint Forces Command Experimentation, 1999–2002

|

Date of Experiment |

Experiment Name |

Type of Experiment |

|

June/September 1999 |

Attack Operations 2015 Against Critical Mobile Targets |

Human-in-the-loop virtual simulation |

|

January 2000 |

Non-kinetic Technologies Limited Objective Experiment |

Constructive simulation |

|

June/August 2000 |

Rapid Decisive Operations Joint Analytic War Game |

War game with constructive simulation |

|

June/October 2000 |

Attack Operations Against Critical Mobile Targets |

Constructive simulation |

|

July/September 2000 |

Millennium Challenge 2000 Joint Field Experiment |

Field experiment |

|

May 2001 |

Information Presentation LOE |

Laboratory staff experiment |

|

June 2001 |

Rapid Decisive Operations in 2007 Joint Concept Refinement Experiment |

War game with human-in-the-loop simulation |

|

October/November 2001 |

Operational Net Assessment LOE |

War game with human-in-the-loop simulation |

|

December 2001 |

Effects Tasks Order LOE |

War game with human-in-the-loop simulation |

|

July/September 2002 |

Millennium Challenge 2002 Joint Field Experiment (MC 02) |

Field experiment |

|

SOURCE: Richard Kass, Chief, Analysis Division, U.S. Joint Forces Command, presentation to the committee on July 30, 2002, Norfolk, Va. |

||

At present, major joint experiments are scheduled at 2-year intervals. These high-level experiments, exercises, and demonstrations require ongoing coordination, as well as interaction by all the Services to ensure that Service equities are protected in terms of cost, operational tempo, and forces participating. At the time of this writing, the first major joint experiment, Millennium Challenge ’02, had just finished, so most of the lessons learned to date from this large-scale field exercise/experiment have come from its planning and preparation stages.

Millennium Challenge ’02 (MC 02)

Millennium Challenge ’02 was a congressionally mandated field exercise/ experiment that combined a number of goals, including troop training and Service experiments (e.g., the Navy’s Fleet Battle Experiment-Juliet (FBE-J) and the Marine Corps Millennium Dragon 2002 experiment). The mission statement for

MC 02 reads as follows: Conduct Millennium Challenge 2002 from July 14 to August 15, 2002, using the western training and testing ranges to (a) determine the extent to which the joint force is able to implement the principles of Joint Vision 2020 to execute rapid and decisive operations in this decade; and (b) produce [DOTMLPF] recommendations for [QDR 05 and budgets 04-09 on those actions that must be accomplished to] ensure the success of the Joint force in this type of operation.7

It is noted here that USJFCOM was not able to design, plan, and execute MC 02 in accordance with its desired plan. Although USJFCOM had been working on MC 02 for some time, the official “tasking” for the event was received via congressional mandate in the National Defense Authorization Act for 2001. In essence, USJFCOM was asked to develop and execute a major experiment in a very short time.8 Given this guidance, USJFCOM conducted MC 02 as required.

By any measure, MC 02 was a large and complex field exercise. Approximately 13,500 personnel took part at 17 simulation locations and 9 live-force training sites, in a large, networked environment ranging from the seas off southern California, through the Midwest, and to a number of East Coast locations. Some 42 models and simulations were linked together, and to the live players, through networks to form a one-time Joint Experimentation Federation. The exercise involved a Navy battle group, a Marine expeditionary brigade, Army airborne and medium brigades, an aerospace expeditionary force, and joint special operations task forces. As mandated, the exercise itself lasted approximately 3 weeks, of which 10 days were devoted to live action.

In a briefing to the committee, USJFCOM provided observations based on lessons learned in the workups to MC 02. The observations refer to the capabilities explored in MC 02 (see Box 4.1). These points formed the basis for discussion in the after-action review that immediately followed MC 02.

A summary of the Navy’s assessment of its participation in MC 02 is given later in this chapter.

The Costs of Millennium Challenge ’02

Several times the committee heard that the total cost of MC 02 was approximately $250 million, including the costs of the Services and of USJFCOM.

|

7 |

CAPT Richard A. Feckler, USN, U.S. Joint Forces Command, J9239, “The Millennium Challenge, ‘The Scene Setter,’” presentation to the committee on July 30, 2002. |

|

8 |

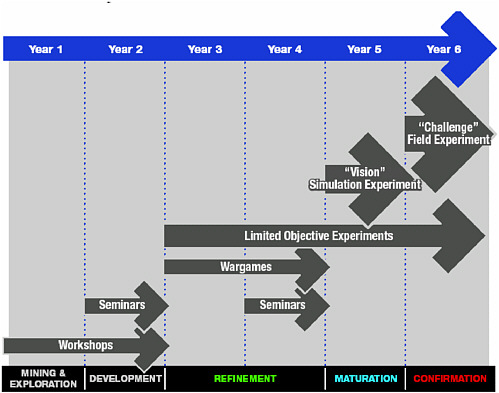

The “normal” time is the 6-year cycle shown in Figures 4.2 and 4.3 in this chapter. The figures are from USJFCOM’s planning documents. As USJFCOM got off to a late start for MC 02 (owing primarily to the first-time nature of many aspects of MC 02 and the congressionally mandated dates for the experiment), it had about 3 or 4 years to plan and execute MC 02. As the experimentation cycle evolves, there will probably be as many as three current experiments in the cycle at any one time. |

|

BOX 4.1

|

However, it has not been able to verify this figure or to determine which costs might be included in this total. It is true that significant forces of each of the Services were fielded; these included major elements at regiment, wing, and battle group levels. However, since the Services also were conducting their own experiments (such as FBE-J) at the same time, the incremental “joint” cost of MC 02 was almost certainly lower than this total. This amount may not be excessive from the standpoint of meeting the congressional requirement for joint field experiments. However, the committee believes that to apply resources effectively, it is necessary to select those venues that may be considerably less expensive but that provide the required knowledge (e.g., wargaming, simulations, and smaller, more focused live experiments) and reserve the larger-scale field experiments for objectives that only they can address.

U.S. Joint Forces Command’s Emerging Concepts

Table 4.2 lists the current set of joint concepts that USJFCOM is formulating together with the committee’s understanding of its current assessment status. To date none of the concepts has been validated or accepted, but some have been subject to initial assessment in MC 02. It is still too early to comment further on these concepts.

TABLE 4.2 Emerging Concepts from the U.S. Joint Forces Command

|

Name of Concept |

USJFCOM Description |

Subject to Initial Assessment in MC 02? |

|

Effects-Based Operations (EBO) |

EBO is defined as a process for having a desired strategic effect on the enemy through the synergistic and cumulative application of the full range of military and nonmilitary capabilities at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels. |

Yes |

|

Rapid Decisive Operations (RDO) |

RDO is an evolving concept for how the joint force, acting within an interagency context, can defeat a capable regional power in weeks rather than months. It explores future joint operations with future military and crisis management. |

Yes |

|

Standing Joint Force Headquarters (SJFHQ) |

USJFCOM postulates an SJFHQ assigned to each theater combatant commander and embedded in the combatant commander’s staff under the direction of a flag or general officer. When a contingency requires the establishment of a Joint Task Force (JTF), the SJFHQ can immediately form the JTF. |

Yes |

|

Adaptive Joint Command and Control (AJC2) |

AJC2 is focused on how the SJFHQ internal organization and joint force information transfer and C2 processes can best be developed to ensure the full realization of the forces’ capabilities to conduct RDO and to adapt rapidly to changing information. |

No |

|

Operational Net Assessment |

Operational net assessment envisions a systematic review of enemy motivations, objectives, alternative courses of action, and sources of strength and weakness, together with an equivalent understanding of U.S. and allied strengths and vulnerabilities as they bear on a conflict. |

Yes |

|

Joint Interactive Planning |

Joint interactive planning is a parallel, collaborative, and adaptive planning process enabled by distributed interactive information systems that will allow supporting staffs and centers of technical expertise, separated by geography, time, and organizational boundaries, to interact in developing options and plans. |

Yes |

|

Interagency and Multinational Operations |

This new J-X staff element would include members from other U.S. departments as well as from coalition states and possibly nongovernmental organizations. The J-X would facilitate interagency coordination and effective multinational operations. |

Yes |

|

Name of Concept |

USJFCOM Description |

Subject to Initial Assessment in MC 02? |

|

Common Relevant Operating Picture (CROP) |

The CROP will store and make immediately available current and archived information as appropriate to all force and command echelons, including (through the use of multilevel security) multinational partners and nongovernmental organizations. |

No |

|

Assured Access |

Assured access refers to the ability to rapidly set and sustain the battlespace conditions necessary to bring the joint force within operational reach so that it can have the desired effects on an adversary. |

No |

|

Focused Logistics |

Focused logistics addresses capabilities necessary to achieve rapid force deployment and agile sustainment, and to help assure access. |

No |

|

Joint Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (JISR) |

JSIR is an actively managed joint capability directing sensors at all levels to collect and integrate information of the highest strategic, operational, and tactical value. |

No |

|

Information Operations (IO) |

Information operations are the elements of information superiority that focus on the attitudes and perceptions of decision makers and the information systems and processes that support decision making. As such, IO is the information equivalent of maneuver and fire power. |

No |

|

SOURCE: The committee derived this overall list of concepts and descriptions from USJFCOM’s document The Joint Concept Development and Experimentation Campaign Plan, FY 2002-2007, dated Feb. 11, 2002, pp. 15-18; the list of concepts included in MC 02 from USJFCOM’s pamphlet entitled “Millennium Challenge 2002 Experimental Objectives”; and initial assessment results from the Navy’s “Quicklook Report on Fleet Battle Experiment Juliet,” dated August 2, 2002. |

||

Synopsis of Results of U.S. Joint Forces Command Experimentation to Date

The results of joint experimentation should, in coming years, flow directly from USJFCOM’s mission to “(a) discover promising alternatives through joint concept development and experimentation; (b) define enhancements to joint warfighting requirements; (c) develop joint warfighting capabilities through joint

training and solutions; and (d) deliver joint forces and capabilities to warfighting commanders.”9 Given this mission, joint experimentation results will consist mainly of DOTMLPF recommendations and warfighting concepts. However, since joint experimentation is still in its early stages, as yet it has resulted in few changes.

As of this writing, USJFCOM had submitted for action three sets of DOTMLPF recommendations to the Joint Staff Force Structure, Resources, and Assessment Directorate (J-8) for presentation to the JROC, but none had yet been approved. These recommendations concern collaborative environments and tools, training for time-critical targeting related to theater missile defense, and joint intelligence preparation of the battlespace, again focused on theater missile defense.

The recent efforts of USJFCOM in Millennium Challenge ’02 and for the next several years focus on two overarching concepts: (1) improving joint command and control through Standing Joint Force Headquarters (SJFHQ) and (2) conducting more effective joint operations through a new approach called Rapid Decisive Operations (RDO), although this latter focus may shift to the Joint Capstone Concept being developed by the Joint Staff.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Secretary of Defense have directed USJFCOM to continue prototyping and validation of the SJFHQ in order to deliver its software and hardware components to each of the regional combatant commanders. No JROC decision will be needed in this case. Prototyping and experimentation will be carried out primarily through Combatant Command exercises. The first installations of these prototypes are currently planned for FY 2005 (at the end of calendar year 2004). The USJFCOM Joint Training and Joint Warfare Center (J-7) has the lead on actual delivery, but SJFHQ activities are also currently the top priority for J-9, which will be heavily involved in further conceptual development and experimentation.10

RDO is still in the experimental stage, but the first experiments with its associated concepts appear promising to USJFCOM. As this report is being written, it appears that USJFCOM’s focus is shifting toward the Joint Capstone Concept now in review by the Joint Staff. In addition, J-9 has written a Joint Concept of Operations, and the Army and Air Force have produced a Joint Operational Concept. All of these concepts have been informed by the basic tenets of the RDO concept. These three overarching concepts, and possibly others, will be examined and competed in a series of war games in the campaign “Pinnacle Impact,” and the result will form the basis for USJFCOM’s future concept development activities.11

|

9 |

USJFCOM mission statement, available online at <http://www.USJFCOM.mil/about/about1.htm>. Accessed December 1, 2002. |

|

10 |

According to committee correspondence with USJFCOM J-9 support staff, August 2002. |

|

11 |

According to committee correspondence with USJFCOM J-9 support staff, August 2002. |

Future Experimentation of the U.S. Joint Forces Command

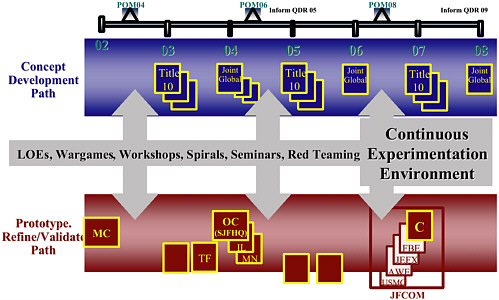

USJFCOM’s future plans involve a 6-year integration of concept development, experimentation, and prototyping through analysis, gaming, and several levels of both joint and Service experimentation (Figure 4.1).12 This plan defines a concept development path, which includes the new “Title 10 Joint Wargame,”13 also called Joint Global Wargame (JGW). It also defines a “continuous experimentation environment” path, with spirals of workshops, games, LOEs, red teams, and so on. In parallel with these are Millennium Challenge, Olympic Challenge (OC), and other major events including FBEs, Joint Expeditionary Force Experiments (JEFXs), and AWEs.

This strategy puts USJFCOM at the center of all concept development and experimentation. Moreover, USJFCOM conducts the training of the Combatant Commands’ Joint Headquarters. USJFCOM is in a position to exercise considerable influence on all Service experimentation, and its emerging Continuous Experimentation Environment may significantly affect future experimentation. In short, as USJFCOM’s role in experimentation grows, its campaign plans are likely to significantly influence naval experimentation in the near-term future. Consequently, NWDC has established a liaison element at USJFCOM, and the Marine Corps has provided an on-scene detachment of its Joint Concept Development and Experimentation (JCDE) division.

USJFCOM’s first track, the concept development track, comprises Service Title 10 war games in the odd-numbered years, alternating with Joint Global Wargames in even-numbered years. JGWs are intended to be “capstone” joint war games, similar in design and construct to Service Title 10 war games, which serve as the integrating vehicle for Service concepts and capabilities. JGW 2004 will be centered on a future joint warfighting concept with associated enabling capabilities, with emphasis on the next decade’s application of Effects-Based Operations. A number of earlier workshops, white papers, and experiments will lead up to this event, including Multinational LOE No. 2, Army Transformation Wargame 2003, Pinnacle Impact 2003, Navy Global Wargame 2003, and so forth.

The second track is designed to prototype, refine, and validate the first path. It currently consists of joint field exercises (Millennium Challenge, Olympic Challenge) in the even-numbered years, with Service experiments such as FBEs, JFEXs, AWEs, and Marine Corps experiments wrapped into these joint experiments.

FIGURE 4.1 Emerging transformation strategy of the U.S. Joint Forces Command.

SOURCE: John A. Klevecz, Assistant Director for Futures Alliance, Joint Experimentation, U.S. Joint Forces Command, “Future Joint Warfighting,” presentation to the committee on July 30, 2002, slide 18.

Several USJFCOM briefers expressed the opinion that Olympic Challenge 2004 will likely be smaller and less ambitious than MC 02, although this remains to be seen. In particular, fresh mandates could well produce another field experiment similar in scale to that of MC 02. If so, this would require USJFCOM to plan and execute a major experiment in one-third of the proposed 2004 timeframe.

Emerging Strategy of the U.S. Joint Forces Command for Experimentation Campaigns

On the basis of experience gained in recent years and in response to lessons learned in the Millennium Challenge process, USJFCOM has defined a regular schedule for annual experimentation events—the simulation-based Vision experiments, cycled with the field-based Challenge experiments. “Vision” events are focused on concept development. “Challenge” events are aimed at testing concepts more robustly in integrated field experiments.14 The overarching opera-

tional concept or theme to be considered (such as RDO in this decade for MC 02) can be identified early and developed over time. The resources to support these experiments can also be planned in advance.

A regular sequence for these major events and the necessary preparation provide a “battle rhythm” for joint experimentation. As shown in Figure 4.2, this 6-year cycle integrates concept development, experimentation, and prototyping through analysis gaming, and several tests of Service and joint experimentation. It starts with workshops and seminars early in the campaign, war games and limited-objective experiments in midcampaign, and a large simulation experiment to culminate the campaign, followed a year later by a corresponding field experiment. The recurring nature of these activities is important to USJFCOM’s ability to engage Service and Combatant Command staffs on a routine basis. Because of the desired close integration with Service and Combatant Command experimentation activities, understanding the rhythm of this continuous experi-

FIGURE 4.2 The U.S. Joint Forces Command 6-year schedule for an experimentation campaign. SOURCE: Commander in Chief, U.S. Joint Forces Command. 2002. “Figure 3.2: 6 Year Cycle of Concept Development and Experimentation,” The Joint Concept Development and Experimentation Campaign Plan FY2002-2007, Norfolk, Va., p. 27.

mentation is important not only for internal USJFCOM planning purposes but also for experimentation activities throughout DOD.

Figure 4.3 superimposes the activities referred to above on the schedule for the USJFCOM series of experimentation campaigns for Olympic Challenge 2004, Pinnacle Challenge 2008, and Zenith Vision-09. These detailed, comprehensive schedules are required to support proper experiment design, planning, execution, and analysis, and the validation of results. Each campaign follows a 6-year pattern. At any given time, two different campaigns will be in progress, overlapped at different stages of the campaign development.

This 6-year cycle appears reasonable, considering the expenditure of resources required to execute a major experiment and the future potential value of the experiments’ validated results. However, the committee notes that while this wide range of preparatory meetings and ramp-up events is in fact crucial for a well-run and useful joint experimentation campaign, it will surely impose a substantial burden on the Navy—and on the Marine Corps—to properly staff the USJFCOM experimentation campaigns. USJFCOM time lines will also surely influence those for naval experimentation. (These points are the subject of additional discussion in the section below entitled “Naval Linkages to U.S. Joint Forces Command Experimentation.”) The committee also notes the need for and importance of maximizing the use of smaller venues, such as war games, simulations, and smaller field experiments and the continuation of activities beyond the culminating major event to derive the requisite knowledge.

Olympic Challenge 2004 (OC 04), to be conducted in the summer and early fall of 2004, will examine the capabilities needed by a Standing Joint Force Headquarters and the joint force to conduct Rapid Decisive Operations in the 2010–2020 timeframe against a high-intensity regional threat. The experiment is intended to describe “how we fight” as the joint force and to provide significant insights leading to DOTMLPF recommendations for changes to the 2005 Quadriennial Defense Review. OC 04 will have implications for choices of future military capabilities as well as the joint command and control (C2) enhancements that are the most likely focus of recommendations following MC 02. A period of intensive, smaller-scale experimentation and assessment across the joint community and the Services will be necessary after OC 04 to prepare high-confidence DOTMLPF recommendations.

OC 04 will build on and significantly extend MC 02. Following MC 02, USJFCOM plans LOEs to refine concepts for the SJFHQ and RDO, as well as supporting concepts, and the Services will refine their proposed capabilities. Concurrent with MC 02 and OC 04, a series of seminars and LOEs will lay the groundwork for the Olympic path joint concept development and experimentation (JCD&E). In 2003, USJFCOM intends to lead the joint community in conducting Olympic Vision 2003, a simulation-based experiment that will be the precursor to Olympic Challenge 2004.

FIGURE 4.3 U.S. Joint Forces Command experimentation campaigns (Olympic, Pinnacle, Zenith). SOURCE: Commander in Chief, U.S. Joint Forces Command. 2002. “Appendix Figure on POM Planning Supporting CPLAN02,” The Joint Concept Development and Experimentation Campaign Plan FY2002-2007, Norfolk, Va., p. 49.

Unlike MC 02, OC 04 will examine potential joint forces and capabilities that are not yet fielded and will be on a scale comparable to Unified Vision 2001. Through the use of prototypes, surrogates, and simulation tools—to the extent possible, all integrated by live joint headquarters with state-of-the-art planning and collaboration tools—USJFCOM will gain insight into the possibilities for major changes in future operations. The intent is that the Services, Combatant Commands, and others will bring their future force concepts and surrogates for their transformed capabilities to the experiment, which will evaluate advances in the tactical and operational levels of warfare, including integrated joint tactical actions. USJFCOM intends for the OC 04 scenarios to include actions by NATO, key allies, and coalition partners and envisions participation by non-U.S. forces in the experiment.

Later, Pinnacle Challenge 2007, to be conducted in the spring and summer of 2007, will explore the extent to which the principles of RDO can be applied to a broader range of the spectrum of joint operations as driven by key themes of a future security environment. This experiment will build on lessons learned from MC 02 and OC 04, as well as from a large number of smaller experiments conducted over the next several years.

U.S. Joint Forces Command’s Emerging Modeling and Simulation Infrastructure

Because modeling and simulation can allow the rapid exploration of the capabilities of future technologies, organizations, and operational concepts without creating new hardware or consuming significant resources in terms of training or personnel, it can both accelerate the pace of experimentation and reduce its cost. Accordingly, it plays a large role in USJFCOM’s vision of future joint experimentation.

In USJFCOM’s view, the 42-model Joint Experimental Federation (JEF) satisfied the essential modeling and simulation needs of MC 02, but even so, this effort was only a first step. Many of DOD’s modeling and simulation tools are based on a limited and legacy set of operational concepts, types of military effects, and defeat mechanisms, and thus are not useful for assessing the value of new operational concepts and capabilities.15 Such legacy simulations are generally not capable of representing a nonlinear battlespace or one filled with a variety of operating units. Nor can they adequately account for information operations, deal with operations other than high-intensity conflict, model the efforts of

nongovernmental organizations, or capture the effects of asymmetric warfare strategies. Many legacy simulations also lack the flexibility to integrate new elements on short notice at reasonable cost. Beyond the simulations themselves, the data analysis tools available to USJFCOM and the larger community are very limited. If the large amounts of data collected in simulations are to be examined in any substantive way, more sophisticated tools will be necessary.

In response to these perceived deficiencies, USJFCOM has identified a path to develop a continuous experimentation environment (CEE) to support all aspects of JCD&E, enabling more flexible, higher-fidelity modeling and simulations, more rapid iterations, and more confident recommendations. In this vision, the CEE would allow experimenters to perform near-continuous experimentation, both locally and at distributed locations to explore multiple questions simultaneously and to ensure that joint considerations are included in all experiments. A continuous experimentation environment would dramatically improve the DOD’s capability to conduct joint concept development and experimentation.

In USJFCOM’s view, the continuous experimentation environment CEE should employ models and simulations that recently formed parts of the JEF in whatever combinations are needed. For example, the Joint Semi-Automated Forces (JSAF) simulation, which was one of the core simulations for MC 02, would serve as a primary tool for entity-level combat. JSAF today can simulate up to 50,000 systems in a common battlespace and is flexible enough to support novel operational concepts and diverse friendly and enemy forces. However, USJFCOM estimates that a system 20 times as powerful would be needed to fully support the needs of joint experimentation. It is claimed that a scalable parallel processing system that can meet this requirement has been demonstrated in prototype form and that with moderate investment it could be available in a near-term timeframe. Service-developed tools would augment JSAF’s high-fidelity simulation, and other JEF models would be federated as necessary to round out the environment.

Finally, USJFCOM is working to adopt for experimentation purposes the Joint Simulation System (JSIMS) training tool. JSIMS-E is intended to provide realistic, large-scale simulations placing humans in realistic operational environments; these simulations would allow interaction with other JSIMS participants and with sensor and other information provided either live or from an archive of earlier experimentation.

The implications of these USJFCOM modeling and simulation developments for the Navy and the Marine Corps are discussed below in the subsection entitled “Naval and Joint Linkages in Simulation.”

The Role of Joint Experimentation in Preparing for Joint Operations

The whole point of joint experimentation is better joint operations. Today, each Service brings its own core warfighting capabilities to the fight. Examples

include carrier-based air capabilities for the Navy, heavy divisions for the Army, stealth bombers and fighters for the Air Force, and amphibious forces for the Marine Corps. These warfighting capabilities are provided from the Services (supporting) to the Combatant Command (supported) for prosecution of the war campaign. But regardless of the command arrangement and structure, the Service forces fight as joint warfighters.

To date, joint and cross-Service experimentation has played three general roles in improving joint operations. Those roles can be summarized as follows:

-

Development of DOTMLPF for the Services and joint community. These developmental improvements are enhancing Service core capabilities, joint capabilities, or both Service and joint capabilities.

-

Better understanding of other Services’ capabilities. Joint experimentation provides a directed forum for the joint participation by all of the Services in a common venue. The Services work together in designing and providing resources for the joint experiment. During these experiments, the coordination and interoperability of Service and joint capabilities (similar to the kinds of interactions required during joint operations) are explored and developed, all leading to improved joint operations.16 Cross-Service experimentation programs provide a similar opportunity since they have reciprocal liaison staff and unit participation.17

-

The less tangible but important aspect of socialization. Participants from different organizations with different Service cultures and perspectives work together toward focused goals. These efforts develop a better understanding and appreciation of the parts that make up the whole, resulting in both a better Service warfighter and a better joint warfighter.

The migration of new joint concepts into actual operations is not easy to trace. However, the committee heard specific anecdotal examples of successes applied in Operation Enduring Freedom. Major General James Mattis, USMC, Commanding General, First Marine Division (REIN) (then Commanding General, First Marine Expeditionary Brigade and the Joint Task Force Commander during portions of Operation Enduring Freedom), stated that some of the innovative operational concepts that he applied originated from his observations in the Hunter Warrior AWE. Rear Admiral David P. Polatty III, USN, Joint Task Force Commander, used several organizational concepts for his staff that resulted from a

series of research experiments and a global war game. Some of these concepts were derived in part from the USJFCOM concept development and experimentation cycle in preparation for MC 02.

There is also evidence that operational experience is helping to guide experimentation plans. USJFCOM briefers stated that lessons learned from Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan have been incorporated in their concepts for experimentation.

NAVAL LINKAGES TO U.S. JOINT FORCES COMMAND EXPERIMENTATION

Since naval operations are joint now and will most likely become even more so in the years ahead, linkages between naval and USJFCOM-sponsored experiments, and indeed the full range of experimental campaigns, should be carefully considered. The range of these campaigns runs from the earliest concept development through analysis, war games, and simulations, leading ultimately to LOEs and the large field experiments such as the Millennium Challenge series. An orderly progression of activities from concept development through experimentation will greatly aid in the efficient use of Service and joint resources.

In all phases of the campaigns, joint experimentation must coexist with Service-specific experimentation, because proficient Service core capabilities are a prerequisite for joint warfighting. Just as there is a specific hierarchy for training purposes (individual, unit, organizational, combined/joint), so there is a natural hierarchy for experimentation. The individual Services need ramp-up time before they bring new warfighting capabilities to the joint effort. To fine-tune their current capabilities and develop new capabilities, the Services must invent or improve their warfighting concepts, design experimentation programs, and conduct Service-unique experimentation to help validate their concepts. For major changes this can be a long, arduous process, requiring continuity and resources throughout a long-term experimentation campaign.

As described above, USJFCOM has laid out a detailed and intense joint experimentation campaign. The Services are directed to support and participate in this effort. These staff demands will stretch the already resource-limited Service-specific experimentation efforts. If, in the worst case, USJFCOM’s activities interfered with or prevented the “normal” progression of Service experimentation, they could actually be counterproductive to developing improved joint capabilities. Thus, a balance must be maintained, and events and objectives must be synchronized between joint and Service-specific experimentation campaigns. In particular, it is important that Service experimentation programs progress in an orderly fashion so that they can improve the Services and joint capabilities.

Naval and Joint Linkages in Concept Development

As new warfighting concepts are developed, coordination among the Services and the joint community must ensure that individual concepts are compatible and mutually supportive. While concept development occurs throughout the Navy and the Marine Corps, it is focused for these Services, respectively, in the Navy Warfare Development Command and the Marine Corps Combat Development Command as discussed in Chapter 3. On the joint side, concept development is done in the U.S. Joint Forces Command and, more recently, also as part of the Joint Warfighting Capabilities Assessment (JWCA) process of the Joint Staff, the results of which are reported to the Joint Requirements Oversight Council.

The NWDC and the MCCDC interact with USJFCOM and (along with other elements of the Navy) the JWCA process in concept development activities, but in the committee’s opinion this interaction is not particularly close. On the basis of information presented to it, the committee makes the following observations on this interaction:

-

The extent of specific interactions with the joint community or other Services in the developing and refining of naval concepts does not appear to be large.

-

The development of joint concepts by USJFCOM and the JWCA process does not appear to build on the naval concepts that are being developed by NWDC and MCCDC.

-

The “joint community” itself does not at present speak with a single voice.18 While responding to the same general themes, USJFCOM and the JWCA process are developing different sets of concepts.19 A detailed correlation between these sets of concepts does not appear to have been established.

Naval and Joint Linkages in Simulation

“Simulation” in the present context refers to virtual and constructive simulations, as distinct from live forces. In this context, there are two subjects to be addressed: (1) naval participation in joint simulations and (2) the potential development and use of a common simulation environment by the Navy, Marine Corps, and USJFCOM.

Naval participation in joint simulations, which has occurred for years, is clearly valuable. At times the Navy participated in joint experiments involving

completely simulated environments (e.g., Unified Vision 2000 and 2001); however, it has primarily employed such simulations within the larger context of live field experiments that also involve actual deployed forces. It is true that deployed forces add a valuable element of realism, but much can be learned using virtual and constructive experiments, especially at the operational level of war. As the Navy begins, for example, to work through the concepts presented in the CNO document “Sea Power 21,”20 virtual and constructive simulations can provide a very useful environment for developing, exploring, and testing the concepts of operation before trying them out with actual forces. Successful realization of these new concepts of operation may require many iterations within the next few years. This would be feasible in a simulation environment, but not in one requiring the use of deployed forces.

A series of (virtual and constructive) simulation-based limited-objective experiments will begin in FY 2003 to prepare for Olympic Challenge in FY 2004. Since the Navy will participate in these LOEs, it has an opportunity to better develop its use of virtual and constructive environments for experimentation purposes.

The development and use of a common naval/joint simulation environment are desirable, although the Navy and Marine Corps will also need their own naval-specific simulations. Such an interoperable environment brings twofold benefits: a consistent environment for both joint and naval-only play, and the cost economies of developing one environment to serve two (or more) communities. In the specific naval/joint context, a common environment should be greatly facilitated by the fact that the JSAF simulation forms the core of both the current USJFCOM and Navy simulation environments. The Marine Corps also uses JSAF,21 although the Joint Conflict and Tactical Simulation (JCATS) was the basic simulation it used in Millennium Challenge ’02.

USJFCOM has recently identified a significant list of desired enhancements to its modeling and simulation capabilities (see above, the subsection entitled “U.S. Joint Forces Command’s Emerging Modeling and Simulation Infrastructure”). These enhancements could meet needs of the Navy and Marine Corps. Navy sources have indicated particular interest in greater fidelity in representing intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance data and weapons effects. Marine Corps sources indicated the need for greater human intelligence play (e.g., reconnaissance patrols). Another potentially useful area involves the representation of nonkinetic aspects of warfare—for example, information operations. This issue

raises the overarching questions of how much of information operations is actually modeled in the simulation, and how much the simulation results depend on how the simulation is used (i.e., the operator actions driving the simulation). At the very least, it would seem necessary to have the simulation represent the capability degradation effects that can be brought about by information operations. Overall, USJFCOM and the Navy and Marine Corps (and other Services if they are involved) will need to agree on the priorities given to the various enhancements because their full undertaking would represent a significant expenditure of resources.

Naval Participation in Joint Field Experiments

The Navy and the Marine Corps have actively participated in joint field experiments for some years, with increased emphasis on these activities in recent events such as Millennium Challenge in the years 2000 and 2002. Representatives from both Services indicated to the committee the clear value of joint field experiments, but at the same time they noted the need for Service-specific experimentation so that the Services could adequately develop their own core competencies. They further pointed out the increased demands that joint experimentation places on their already highly committed forces and personnel, as well as the increased financial commitments that are necessary. Marine Corps representatives in particular noted that the extensive number of meetings occurring as part of the joint concept development and experimentation process was taxing its limited staff resources.

Thus, within the limited resources available, there is a need to obtain the proper balance between joint and Service-specific experimentation and to establish the appropriate priorities among all the various activities. At present, no formal mechanism exists for accomplishing this objective. The matter of achieving balance, by no means an easy task, is mentioned briefly at the end of this chapter and is addressed in detail in Chapter 6.

Historical Perspective

The Navy participated in numerous joint experiments prior to MC 02. MC 00, JEFX-1999, and JEFX-1998 are a few examples at the operational level. Outside the specific USJFCOM context, the Navy air arm has long participated in joint training exercises with USAF, including some experimentation that was transparent and nondetrimental to the exercise training objectives; the USAF tactical Red and Green Flag exercises at Nellis Air Force Base are examples. In addition, the Navy has a long tradition of wargaming at the operational and strategic level at Newport, Rhode Island; these war games have featured joint participation. The Navy has also participated in other Services’ operational and war games ranging from the operational to the strategic.

TABLE 4.3 Navy and Marine Corps Initiatives in Millennium Challenge ’02

|

Type of Initiative |

Specific Initiatives in MC 02 |

|

Technical initiatives |

Joint Fires (Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC) sponsor) |

|

Service-level integration initiatives |

High-Speed Vessel (HSV) (NWDC and MCCDC sponsors plus others) |

|

Navy Service initiatives |

Joint and Maritime Component Commander Ship-Based Joint Command and Control Netted Force (distributed C2, coalition) Naval Fires Network—experimental Unmanned Sensors, Unmanned Platforms Theater Air Missile Defense Antisubmarine Warfare Antisurface Warfare Mine Warfare Information Operations |

|

Marine Corps Service initiatives |

Urban Combined Arms Exercise Local Area Security System Universal Combined Arms Targeting System |

|

SOURCE: Derived from U.S. Joint Forces Command. 2002. “Millennium Challenge 2002, Forging Our Nation’s Future Joint Force,” Norfolk, Va. |

|

Millennium Challenge ’02

By far the largest joint experiment to date, Millennium Challenge ’02 deserves special attention. The Navy’s Fleet Battle Experiment-Juliet (FBE-J) and the Marine Corps Millennium Dragon 2002 experiment were conducted within the general framework of MC 02. They were quite large experiments in their own right. In terms of naval forces, MC 02 involved a Navy battle group and a Marine expeditionary brigade, as well as the extensive simulated representation of other forces. MC 02 initiatives involving Navy and Marine Corps sponsorship are shown in Table 4.3.

Initial Assessments of Naval Participation in Millennium Challenge ’02

Table 4.4 presents, in highly summarized form, the Navy’s “QuickLook”22 assessment of Navy-specific objectives in MC 02. These are the only results

TABLE 4.4 Navy “QuickLook” Assessment of Navy-Specific Objectives in MC 02

known to the committee as of this writing. Since the analysis of MC 02 results has just begun, it is too early to discuss or comment on this assessment further.

A few major points were highlighted in the “QuickLook Report” for FBE-J. The most relevant of these are captured in the following paragraphs.

First, the high-speed vessel (HSV) was commended for its flexibility, speed, and modular design. The report states that additional experimentation and operational integration are “clearly warranted” and recommends that a second such vessel be leased and its capabilities assessed across the full range of littoral operations.

Second, the “QuickLook Report” strongly recommends a sweeping upgrade of the existing modeling and simulation environment, stating that “both the Navy and the Joint Community must improve the distributed simulation environment,” since simulation is a vital augmentation even of these very large exercises. Unfor-

tunately, the current modeling and simulation federation cannot simulate the emerging network-centric environment, creating serious limitations in the exploration of advanced concepts in MC 02. The “QuickLook Report” recommends either that the entire joint community move to a single (new) simulation environment, or that the existing environment be “radically improved.”

Finally, the report notes that meaningful deployment of network-centric warfare concepts has been held back by lack of sufficient bandwidth available to deployed forces, but it notes that NWDC, with the help of the Naval Research Laboratory, has provided experimental links (via commercial satellite service) of 2 to 4 megabits per second to surface combatants and as much as 54 Mbps to a command ship. The committee continues to believe that per-ship bandwidth is a pressing concern, and it is extremely supportive of these experimentation efforts. NWDC deserves great credit for its ongoing and highly skillful work in this arena.

Committee Observations on Naval Participation in Millennium Challenge

On the basis of briefings and other information provided from the Navy, the Marine Corps, and USJFCOM, the committee makes the following, general observations with respect to Millennium Challenge ’02:

-

The value of such a large experiment relative to its cost was questioned both by a number of briefers and by many committee members. Some felt that such a large sum could be put to better use in a series of smaller experiments both of the joint and the Service-specific type. Others noted, however, that such an event made the assets of other Services available, which is difficult to accomplish in the context of smaller experiments because of all the demands on operational assets. There was full agreement that it is extremely important to select the venue that matches the objectives desired. A large-scale field experiment may be warranted to test integration, scalability, and a complex set of interactions. But the question remains—How large a scale is necessary?

-

Such large, high-visibility experiments were characterized by many as demonstrations, rather than experiments. In demonstrations there is little room for true exploration or failure. If that is the case, such events may provide some opportunities to showcase unfunded but “ready-for-prime-time” equipment capabilities in hopes of garnering support and supplemental funding. Others noted, however, that the series of smaller events conducted over the 2 years leading up to MC 02 allowed for greater exploration and assessment.

-

The greater use of simulation relative to the use of live forces would allow more experimentation in the future, especially for concepts that apply above the tactical level. For example, the Standing Joint Force Headquarters, one of the main concepts tested in MC 02, could perhaps have been adequately explored with few if any live forces or real platforms.

-

Ongoing naval participation is essential during the planning stages for major joint experiments in order to ensure that Service experiment objectives are included in the formal list of joint experiment objectives. In this respect, the Navy and the Marine Corps have done well to date; in MC 02, the Navy had 10 Service objectives and the Marine Corps had 3 included in the joint experiment plan.

Joint Experimentation at the Tactical Level

A final perspective for looking at naval involvement in joint experimentation is that of the command level involved: that is, the Joint Task Force (JTF) level, component (maritime, land, or air) level, or tactical level. In joint experiments to date, most joint participation of the Services has been at the JTF level, with some lesser degree at the component level. This raises an important question for the future: Can and should greater concept development and experimentation be conducted jointly at the tactical level? It appears that this will be necessary, given the joint interaction that was witnessed in tactical operations in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (e.g., Army Special Operations Forces directing fire from Navy and Air Force aircraft).

It is yet to be determined how best to accomplish greater concept development and experimentation conducted jointly at the tactical level. The committee notes that USJFCOM appears to be pushing downward by influencing experimentation at levels below its original JTF perspective, although perhaps mostly only to the component level. The Services appear concerned about losing their prerogatives in this way, and with some reason. Perhaps this is a matter to be worked out in cross-Service (vice joint) forums.

The Price of Naval Participation in Joint Experiments

Experimentation is an important part of transformation—in fact it might be viewed as the engine of change—but experimentation certainly comes with a price tag. Many elements of this “cost” can readily be quantified in dollar terms, but the cost of other very real elements can be difficult to quantify. One important area is the cost in terms of human resources.

The number of personnel needed for the actual execution of an experiment is easily visible, but the human resource requirement for experiment planning is less so. Not only are there a variety of technical activities associated with the design of the experiment, but there are also numerous coordination activities. For example, Figure 4.3 indicates that more than 100 separate events are scheduled for joint experimentation in the FY 2004–FY 2009 period. Each of these will most likely require numerous meetings and related activities. The limits imposed by resource constraints and the demands of real-world operations tempo mean that the personnel demands cannot be easily met. However, the situation does

argue for the joint and Service communities to confront this matter as judiciously as possible—by avoiding unnecessary or redundant activities and holding experiments to the minimum size necessary to accomplish their objectives.

EXPERIMENTATION IN THE COMBATANT COMMANDS

The November 2002 guidance issued by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, as previously quoted, states that “[USJFCOM’s Joint Experimentation Campaign Plan] must incorporate a decentralized process to explore and advance emerging joint concepts, proposed operational architectures, experimentation and exercise activities currently being conducted by … the combatant commands [and specified other entities].”23 Thus, while USJFCOM is the executive agent for joint experimentation, such experimentation also takes place in the Combatant Commands beyond those experiments directly organized by USJFCOM. In fact, the issues involved in joint force operations are so important and large in scope that it is only natural that all Combatant Commands should be involved in addressing them through experimentation.

The primary responsibilities of a Combatant Command can be summarized as follows:

-

Readiness—being prepared to respond to contingencies, from small crises to major conflict;

-

Security cooperation—conducting activities to build regional coalition capabilities to carry out common missions; and

-

Transformation—adapting force operations to take best advantage of new concepts and technology to meet existing threats and to be prepared for possible future threats.24

While the first two items above have long been considered the responsibilities of a Combatant Command, today’s world environment has also elevated the third to key importance. The Combatant Commands must be prepared to meet the threats evolving today in the theaters. In this regard, the Combatant Commands bring a unique perspective complementary to other transformation efforts in the DOD—that is, their understanding of emerging and potential threats in terms of the concrete aspects of a specific geopolitical context.

Combatant Command exercises (which may involve war games and simulations as well as live forces) provide a major vehicle for addressing all three responsibilities: Exercises train U.S. forces, thereby helping to maintain readiness. When involving coalition forces, they help build cooperative operational procedures among U.S. and coalition partners. And when involving an element of experimentation, these exercises also lead toward transformation.

The inclusion of experimentation within exercises warrants further comment. Some look upon this negatively while others favor it. The following quotation gives one Combatant Commander’s perspective:

Some have contended there must be a bright and shining line between training and experimentation. They say too much experimentation during an exercise on the one hand degrades the training and on the other hand constrains the development of truly revolutionary leaps forward in warfighting concepts. I believe that experimentation meshes well with training. We should incorporate an element of experimentation in our exercises in a way that will accomplish the goals of both and often will enhance both. This is especially true for sensors and communications systems, the keys to information dominance.25

Given that Combatant Commands today must address all three responsibilities listed above—readiness, coalition collaboration, and transformation—the committee finds itself in general agreement with this view. The need to meet all three responsibilities and the limited time and assets available with which to do so means that, realistically, some experimentation must take place within a broader context of exercises. While an experiment conducted within the context of an exercise may not be able to have all the discipline of a “pure experiment,” it should, if conducted correctly, allow for new concepts and technologies to be explored, with the lessons from that exploration being captured and acted upon. The exercise context will require that the transformational capabilities being addressed are largely evolutionary, but certain aspects of transformation may well be built from a sequence of evolutionary steps rather than from one bold revolutionary leap.

When combining experiments with exercises, it is crucial to preserve the objectives of both, although this has often been difficult.26 The committee believes

|

25 |

ADM Dennis C. Blair, USN. 2001. “Change Is Possible and Imperative,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 127, No. 5, May, p. 49. ADM Blair also goes farther with this point in a way that is relevant to this report as a whole. Namely, he argues for “acquisition by adaptation,” whereby a prototype system is put out quickly and adapted and improved as it is fielded, through such venues as exercises. |

|

26 |

See, for instance David S. Alberts, Richard E. Hayes, John E. Kirzl, Leedom K. Dennis, and Daniel T. Maxwell, 2002, Code of Best Practice Experimentation, DOD Command and Control Research Program, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Networks and Information Integration), Washington, D.C., July, Ch. 3, p. 345. Available online at <http://www.dodccrp.org/>. Accessed October 7, 2003. |

that success requires that the experimental objectives, design, conduct, and data collection and analysis must be as rigorous as possible, and that they not be compromised. Success also requires that planning take a “campaign” perspective, since many of the experimental objectives will entail a series of exercises in order to be realized.

To make the points discussed here more concrete, Table 4.5 presents several examples of experiments conducted by Combatant Commands. Some general features of these examples are apparent. First, the experimentation applies largely to command, control, and communications. Second, it takes place in both command post and field exercises, and it pertains both to developing and refining procedures and to testing and refining prototype systems. Third, the experimentation can involve coalition nations, which is significant because future operations—from humanitarian actions through major conflict—would most likely involve coalition partners.

There are numerous examples, such as those cited in Table 4.5. However, there does not appear to be any coordinated program between the Services and Combatant Commands to conduct experimentation within joint exercises in a systematic way.27 Such coordination would involve the organized execution of the following activities by the Service and Combatant Command staffs:

-

Determining cases in which participation in such field events is the most effective venue;

-

Identifying areas of joint operational concepts and tactics (e.g., based on the essential tasks of a joint mission) requiring further development in order to best meet challenges anticipated in the theater;28

-

Identifying Service systems under development that are suitable for examination in experiments;

-

Planning for exercises to most fully accommodate experimentation involving these concepts and tactics and systems, consistent with the other objectives of the exercises; this planning should assume a campaign perspective, since many of the experimental objectives will require the development of a body of knowledge through a series of activities;

-

Conducting the experimental design, data collection, and data analysis necessary to make the experimentation as rigorous as possible;

TABLE 4.5 Examples of Experimentation in Combatant Commands

|

Event |

Nature of Experimentation |

|

Command and Control Exercise (Pacific Command (PACOM), twice yearly) |

Examined information flows between Tier II and Tier III of Joint Task Force (JTF) Headquarters, e.g., involving common operating picture, air tasking orders, and requests for fire power. Improved ability of Tier III components to operate as part of the JTF. |

|

Kernel Blitz (Experimental) (PACOM, 2001) |

Run in conjunction with Fleet Battle Experiment-India (FBE-I) and Capable Warrior AWE; involved forces from all four Services. Explored Wide-Area Relay Network (WARNET) technologies. Supported development of JTF WARNET to provide a secure tactical communications network. |

|

Foal Eagle (PACOM, 1998) |

Run in conjunction with FBE-Delta, incorporating Army assets into that Navy experiment. Demonstrated concept of using Army Apache helicopters against Special Operations Forces infiltration craft, and left behind a system for linking Navy and Army fire control systems. |

|

Internal Look (Central Command (CENTCOM), 2002) |

Tested a deployable joint command and control facility. Helped shake out new capability by examining procedures and communications from theater to continental United States and within theater. |

|

RIMPAC (PACOM, 2000) |

Combined exercise involving seven countries (that rim the Pacific Ocean). Established satellite communications for a coalition wide-area network involving all 50 participating ships, providing connectivity to command ship and data sharing among all ships. Enabled enhanced combined operations. |

|

Cobra Gold (PACOM, yearly) |

Combined exercise with Thailand; also some involvement from Singapore. Helped to work out coalition procedures and networks. |

|

Advanced Concept Technology Demonstrations (ACTDs) |

Each ACTDa has a Combatant Command as its operational sponsor, and exercises can be used to explore and refine the capabilities involved. For example, the Extending the Littoral Battlespace and Commander in Chief (CINC 21) ACTDs, which are providing new C3 capabilities, participated in Kernel Blitz (Experimental). |

|

aThere have been more than 100 ACTDs since the inception of such programs in 1995. |

|

-

Disseminating relevant results of the experimentation (perhaps through USJFCOM) to other Combatant Commands, and considering how in a broader sense the results might influence joint doctrine; and

-

Feeding the results of the experimentation on developmental systems back into the development process (i.e., to support spiral development).

The most direct mechanism for this coordination would be between the Combatant Command and the Service component commands assigned to that Combatant Command (e.g., either the appropriate Navy fleet command or the numbered fleet commands under that fleet command). The component commands could then interact as necessary with other elements of their respective Service (e.g., with NWDC and MCCDC).

In summary, the Navy and Marine Corps and the Combatant Commands cooperate in joint experimentation within exercises conducted in the Combatant Commands—Kernel Blitz is one such example. However, it appears highly desirable that there be more active collaboration of the Navy and Marine Corps and the Combatant Commands to systematically develop programs of joint experimentation. Both large and smaller exercises conducted in the course of routine deployments could be involved, as would both fleet and command post exercises. While there are limitations to conducting experiments within exercises because of the multiple objectives that the exercises themselves must satisfy, there are also numerous benefits to be realized. In particular, the exercises can offer frequent opportunities for joint interaction, they can lead to results being fed directly back into the operational forces, they can support the spiral development process through joint (rather than Service-unique) system use, and they can allow the development of concepts with coalition partners.

Fleet battle experiments have been involved to a limited extent in joint experimentation—for example, as noted in Table 4.5 regarding FBE-D and FBE-I. It appears that the much greater involvement of FBEs in joint experimentation would be a particular opportunity for the Navy to enhance its joint capabilities and to contribute to joint capabilities overall. The FBEs are run under the numbered fleets and, as noted above, those commands provide the most direct vehicle for interacting with the regional Combatant Commands.

CROSS-SERVICE EXPERIMENTATION

Not all experimentation involving two or more Services need take place under the joint umbrella. Although joint leadership of multi-Service experiments should ensure that the experimentation relates to joint concepts and supports joint doctrine development, direct Service interaction can involve fewer complications and costs and greater freedom to innovate. These are obviously advantages. Any useful concepts developed in such direct Service interaction should, however, eventually be fed into the joint arena.

In the committee’s view, concept development and experimentation involving the Services directly is best suited for operations at the tactical level, since higher-level (component and JTF) operations are primarily joint. This direct Service interaction can occur in two general ways—between Service centers involved in concept development and between deployed forces engaged in exer-

cises and experiments. Representatives from Service centers are brought together during joint activities (e.g., Millennium Challenge), but the reason is to work toward some generally predefined purpose; what is envisioned here are interactions allowing greater freedom for the exchange of ideas. In that regard, the Navy Warfare Development Command and the Marine Corps Combat Development Command have regular interaction with one another. In addition, the Navy Network Warfare Command has noted that its proximity to corresponding Air Force organizations (e.g., Air Combat Command and the Air Force Command, Control, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Center) offers the opportunity for collaboration. While other, substantive interactions between Service centers may exist, none were apparent to the committee in its investigations. Increased interaction could be very valuable—to provide cross-fertilization in concept development and to begin building joint concepts from the ground up.

Regarding direct Service interaction in exercises and experiments, the Navy indicated in briefings to the committee that other Services (e.g., the Air Force) are involved in its fleet exercises, and that it would like to increase such involvement, although mutual scheduling is a difficulty. Recent Marine Corps experiments, with their highly tactical focus, do not appear to have a significant joint or cross-Service perspective. However, future opportunities would appear to exist—for example, coordinated operations with Army Special Operations Forces and air support from Navy and Air Force aircraft.

As just noted, one recurrent difficulty with involving another Service in Navy fleet exercises is that of arranging the simultaneous availability of assets from the two Services. Ideally, the elements of both Services should be on exercises (or other, more formal experiments) at the same time. This, however, requires cross-Service coordination of force deployment schedules. Such coordination would have to be carried out at the top levels of the Services—possibly with USJFCOM acting as an intermediary—because the deployment schedules have Service-wide impacts relating to such factors as accomplishing operational missions, training, personnel rotation, and platform overhaul and upgrade.

ENHANCING NAVAL PARTICIPATION IN JOINT EXPERIMENTS

Now is a time of great ferment in military thinking, both within the Navy and the Marine Corps and across the joint community. Changes in the systems for defense requirements generation and acquisition are actively being promoted, and a transformation process is being put into place to develop new military capabilities more rapidly in order to be prepared for future military challenges. The lessons from Operation Iraqi Freedom will further shape the understanding of needed capabilities. Concept development and experimentation figure as a key element in all of these initiatives. Furthermore, since all recent military operations have been joint, and most future operations will likely be so as well, the joint aspects of concept development and experimentation are particularly important.

As this chapter describes, the Navy and the Marine Corps have been active participants in joint concept development and experimentation. However, both the need and the opportunities for greater participation are also recognized here. While the committee’s perspective is primarily that of the Navy and Marine Corps, it is recognized that such participation is a two-way collaboration—that is, the Navy and Marine Corps work toward joint objectives, and the joint authorities are likewise receptive to the particular ideas that the Navy and Marine Corps bring.